The battle, also known as the Battle of Elviña, that ensured the escape of the British army from Spain on 16th January 1809, during the Peninsular War, with the death of Sir John Moore at the moment of success

Sir John Moore at the head of the 50th Regiment at the Battle of Corunna on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by R. Granville Baker

7 . Podcast of the Battle of Corunna: The battle, also known as the Battle of Elviña, that ensured the escape of the British army from Spain on 16thJanuary 1809, during the Peninsular War, with the death of Sir John Moore at the moment of success: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcasts.

. Podcast of the Battle of Corunna: The battle, also known as the Battle of Elviña, that ensured the escape of the British army from Spain on 16thJanuary 1809, during the Peninsular War, with the death of Sir John Moore at the moment of success: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcasts.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Cacabelos

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of the Douro

Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by JJ Jenkins

Battle: Battle of or Corunna (or La Coruña)

War: Peninsular War

Sir John Moore killed at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Sir Thomas Lawrence

Date of the Battle of Corunna: 16th January 1809

Place of the Battle of Corunna: La Coruña in Galicia, North Western Spain

Combatants at the Battle of Corunna: British against the French

Generals at the Battle of Corunna: Major-General Sir John Moore against Marshal Soult

Size of the armies at the Battle of Corunna: Sir John Moore’s army, with Sir David Baird’s corps from Corunna numbered 35,000 men. The Emperor Napoleon’s army numbered 153,000. From Astorgas, Napoleon left the pursuit of Moore’s army to Soult whose corps numbered around 35,000 men.

Uniforms, arms, equipment and training at the Battle of Corunna:

Marshal Soult French commander at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers, and stovepipe shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments wore dark green jackets.

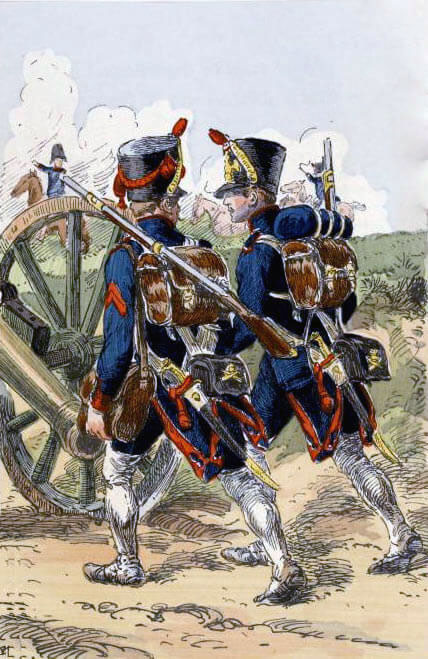

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

Highland regiments wore the kilt with red tunics and black ostrich feather caps.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light cavalry was increasingly adopting hussar uniforms, with some regiments changing their titles from ‘light dragoons’ to ‘hussars’.

The King’s German Legion (KGL) was the Hanoverian army in exile. The KGL owed its allegiance to King George III of Great Britain, as the Elector of Hanover, and fought with the British army. The KGL comprised both cavalry and infantry regiments. KGL uniforms mirrored the British.

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe, and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms like the infantry, the horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket. The musket could be fired at three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for a hundred metres or so. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, which fitted the muzzle end of his musket.

Black Watch officer: Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, and a sword bayonet.

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who invented it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was never able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create his powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns with the speed of the French columns of infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

——————

42nd Highlanders the Black Watch retaking Elviña at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Podcast of the Battle of Corunna: The battle, also known as the Battle of Elviña, that ensured the escape of the British army from Spain on 16thJanuary 1809, during the Peninsular War, with the death of Sir John Moore at the moment of success: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcasts.

Podcast of the Battle of Corunna: The battle, also known as the Battle of Elviña, that ensured the escape of the British army from Spain on 16thJanuary 1809, during the Peninsular War, with the death of Sir John Moore at the moment of success: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcasts.

Winner of the Battle of Corunna: The French; having forced the British army to retreat across north-west Spain, suffering substantial losses and leave Spain by the port of Corunna.

On the other hand, the French felt cheated that the British army was enabled to escape and the British troops considered they had performed well in the battle and their self-confidence was much restored.

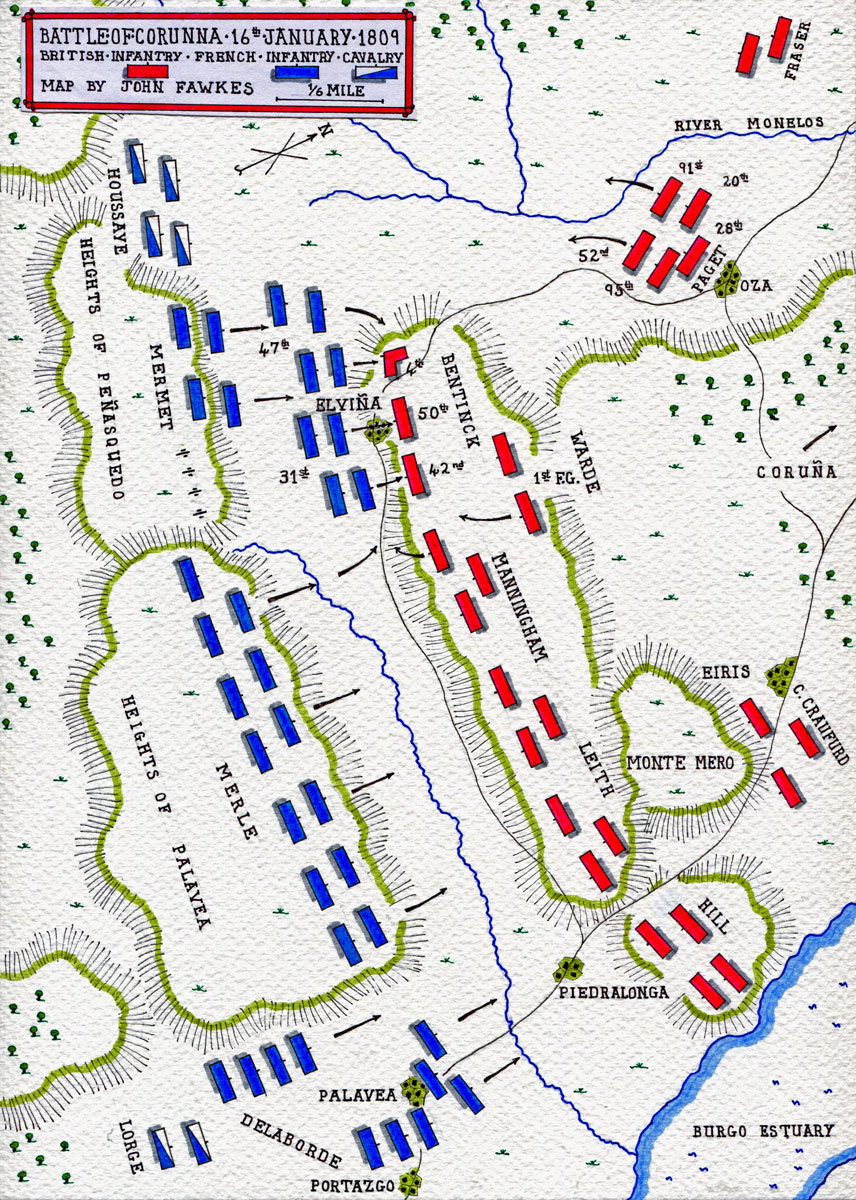

British order of battle at the Battle of Corunna:

Infantry:

First Division: Lieutenant-General Sir David Baird:

Warde’s Brigade: 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 1st Guards

Bentinck’s Brigade: 1st/4th, 1st/42nd and 1st/50th Foot

Manningham’s Brigade: 3rd/1st, 1st/26th and 1st/81st Foot

Second Division: Lieutenant-General Sir John Hope:

Leith’s Brigade: 51st, 2nd/59th and 76th Foot

Hill’s Brigade: 2nd, 1st/5th, 2nd/14th and 1st/32nd Foot

Catlin Craufurd’s Brigade: 1st/36th, 1st/71st and 1st/92nd Foot

Third Division: Lieutenant-General McKenzie Fraser

Beresford’s Brigade: 1st/6th, 1st/9th, 2nd/23rd and 2nd/43rd Foot

Fane’s Brigade: 1st/38th, 1st/79th and 1st/82nd Foot

French Artillery: Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

Reserve Division: Major General Edward Paget

Anstruther’s Brigade: 20th and 1st/52nd Foot and 1st/95th Rifles

Disney’s Brigade: 1st/28th and 1st/91st Foot

Cavalry: Lieutenant General Lord Henry Paget:

Slade’s Brigade: 10th and 15th Light Dragoons

Stewart’s Brigade: 7th and 18th Light Dragoons and 3rd LD KGL

Dowman’s and Evelin’s troops of horse artillery, 12 guns

Royal Artillery park and reserve: Colonel Harding: 5 artillery brigades and 30 guns

French Order of Battle at the Battle of Corunna:

Cavalry:

Lorge’s Division of 13th, 15th, 22nd and 25th Dragoons

La Houssaye’s Division of 17th, 18th, 19th and 27th Dragoons

Infantry:

Mermet’s Division of 31st Light (4 battalions), 47th (4 battalions) and 122nd (4 battalions) Regiments of the Line

Merle’s Division of 2nd (3 battalions) and 4th (4 battalions) Light and 15th (3 battalions) and 36th (3 battalions) Regiments of the Line

Delaborde’s Division of 15th (3 battalions) Light and 70th (4 battalions) and 86th (3 battalions) Regiments of the Line

20 guns

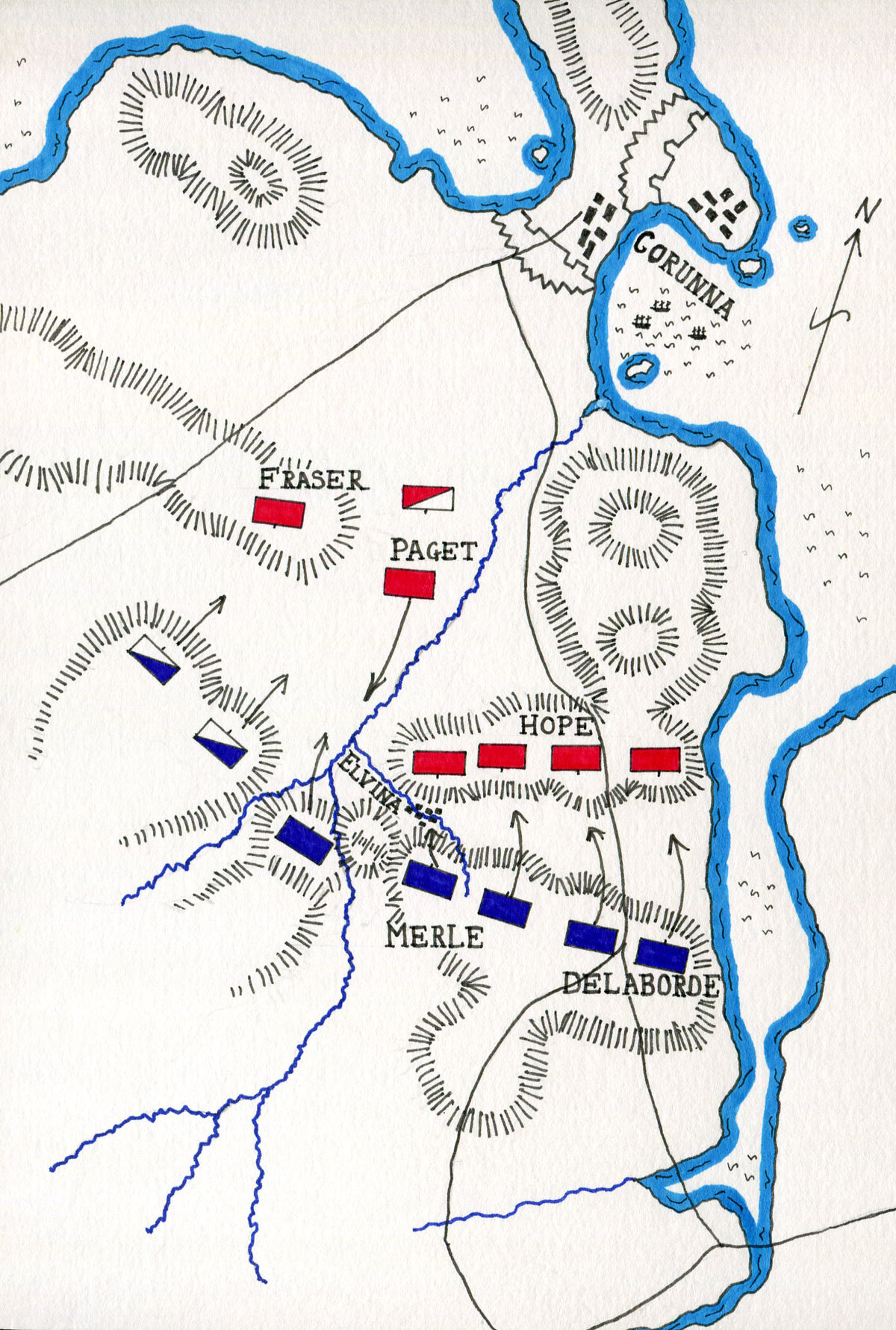

Map of the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

Background to the Battle of Corunna:

At the end of October 1808, the Emperor Napoleon, at the head of a large French army assembled in the northern Spanish city of Vitoria, prepared to place his brother Joseph on the throne of Spain by force.

Several Spanish armies gathered to resist Napoleon. The British corps in Portugal was ordered to advance to Burgos and assist the Spanish.

Major-General Sir John Moore now commanded the British troops in Portugal, following the departure to England of Generals Burrard and Dalrymple and Sir Arthur Wellesley, to face the enquiry into the Convention of Cintra, which had enabled Marshal Junot and his French army to escape from Portugal after the Battle of Vimeiro, being transported to French ports by the British fleet.

Moore commanded 23,000 troops in Lisbon and expected to be re-enforced by 10,000 more men due to arrive at Corunna under Sir David Baird.

As Moore proudly declared, “No British general has commanded so many soldiers since the time of Marlborough”.

Moore sent his infantry by the northern route through Coimbra, Celerico and Badajoz to Salamanca in Spain. Late anxieties about the state of that road caused him to divert his artillery and cavalry by the southern Ciudad Rodrigo road.

Arriving at Salamanca, Moore learnt that Napoleon had defeated the Spanish armies and was already in Burgos, Moore’s intended destination. Soon afterwards, the French entered Madrid. The British army, outnumbered by some two to one, was now threatened. Nevertheless, Moore felt reluctant to abandon the Spanish and advanced on Soult’s corps in Valladolid.

95th Rifles during the retreat to Corunna: Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

Moore had lingered within striking distance of the large French forces for too long. Napoleon was coming after him, and it was imperative that the British army retreat with all speed to Corunna in the north-west corner of Galicia, for evacuation by the Royal Navy.

It was late in the year, 1808, and the retreat was one of great hardship. From Astorgas, Napoleon returned to France and left Marshal Soult to conduct the pursuit.

The British rearguard, comprising General Paget’s reserve brigade, Colonel Craufurd’s brigade and the British cavalry, seized every opportunity to hold off the French. Holding actions were conducted by the cavalry at Benevente, by Paget’s reserve at Cacabelos and by the whole army at Lugo.

Sir John Moore during the retreat to Corunna: Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by R. Beavis

While the main army took the direct route over the Cantabrian Mountains to Corunna, Moore sent the two light brigades on the western road via Orense to Vigo, to secure that route, in case it was necessary to meet the British fleet at that port.

This force comprised Robert Craufurd’s First Light Brigade (1st/43rd, 2nd/52nd Light Infantry and 2nd/95th Rifles) and Charles Alten’s Second Light Brigade (1st and 2nd Light Battalions, KGL).

Other than in the rear-guard, the discipline of many of the British regiments of foot disintegrated and the troops ravaged the countryside and villages through which they passed. A notorious incident took place at Bembibre, where 200 British soldiers became so drunk in a cellar that they had to be left for the French (the figure is officially recorded in a return).

‘Throwing the army’s cash down the mountainside’: Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Gordon Browne

During the retreat, the carts carrying the army’s reserves of cash broke down and the money had to be thrown down the mountain-side, some of it being retrieved by the pursuing French dragoons.

The Battle of Corunna:

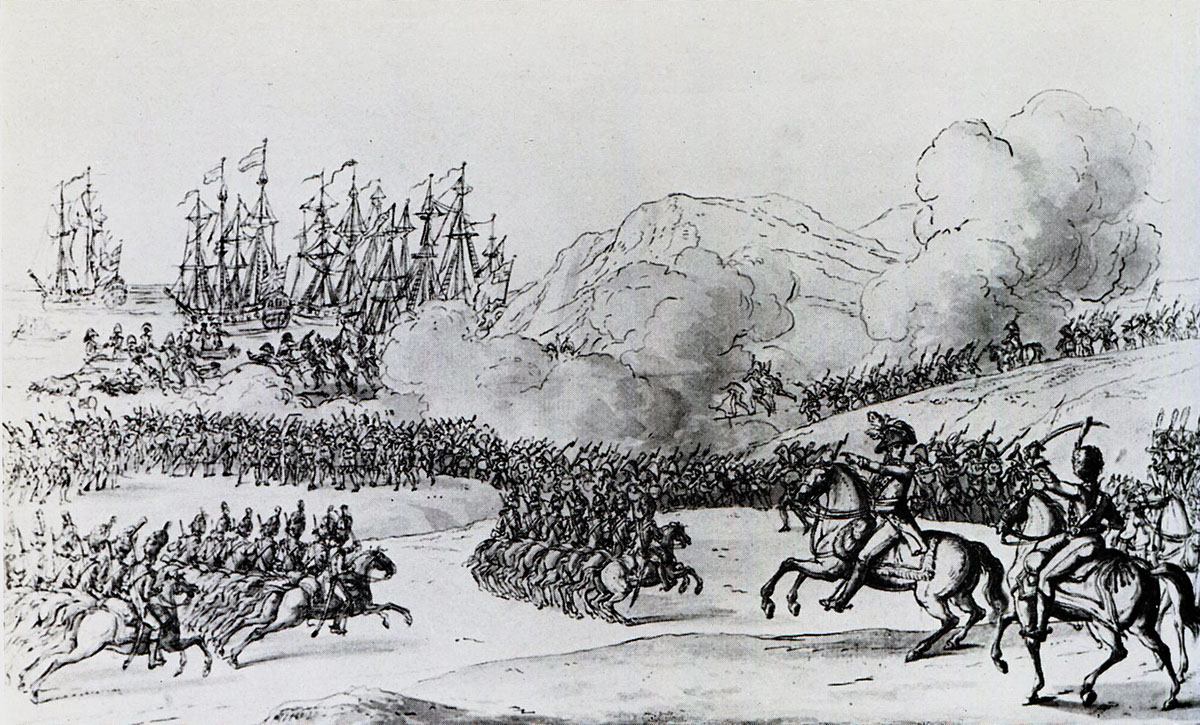

The British army marched into the port of Corunna on the night of 11th January 1809, many of the troops in a state of exhaustion. The French were some distance behind, but the fleet was not in harbour. The transports did not reach Corunna from Vigo until 14th January 1809.

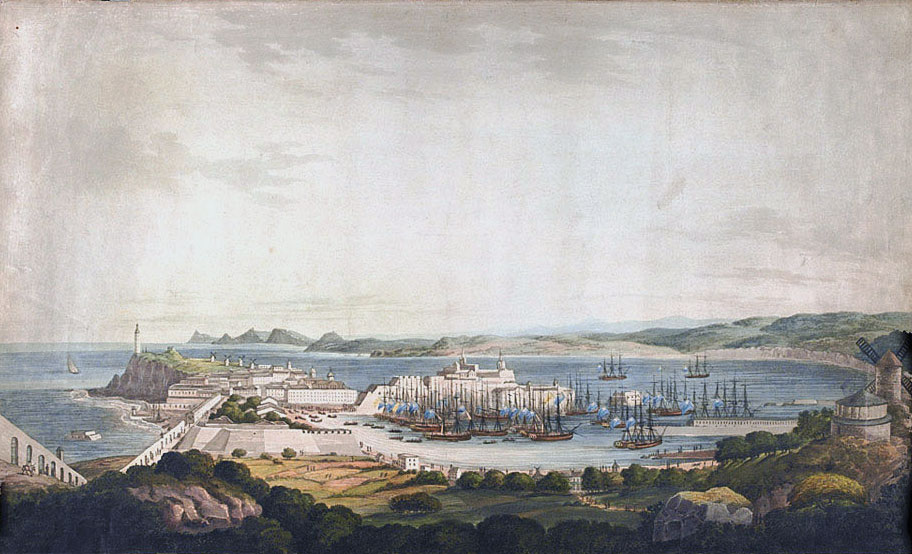

Corunna harbour with the British Fleet at the time of the explosion of the magazine in Corunna: Battle of Corunna on 13th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: water colour sketch by Robert Kerr Porter

On 12th January 1809, Moore embarked the sick and some of the stores on those ships in Corunna harbour and prepared to give battle to the French, while he waited for the arrival of the main fleet.

On 13th January 1809, Moore rearmed his infantry with new muskets from the substantial store held in Corunna and blew up the magazine containing four thousand pounds of gun powder and other equipment that could not be used and would otherwise fall into the hands of the French.

British troops going on board ship at Corunna: Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

Three bridges gave access to Corunna for the pursuing army of Marshal Soult; the bridge at El Burgo on the main Madrid to Corunna road, the bridge further south at Cambria and the most southerly bridge at Cela.

The French had to repair the bridges at El Burgo and Cambria, damaged by British engineers, before Soult could launch an attack on Moore’s army.

French infantry began to infiltrate across the El Burgo bridge late on 13th January 1809 and occupied the village of El Burgo.

On 14th January 1809, French cavalry and guns were able to use the bridge and begin the build up for the attack on Moore’s army, waiting around Corunna to leave Spain.

The British transport fleet arrived in the harbour late on 14th January 1809 and the British embarked the dismounted cavalry with a thousand horses and 50 guns.

British gunners loading their guns on board ship: Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Benjamin West

8 British and 4 Spanish guns were kept ashore with teams of horses.

The sight of the arriving British ships stimulated Soult to begin his attack, after some prevarication.

Moore’s main position lay along the Monte Mero ridge, running west to east, from the village of Elviña to the Burgo Estuary.

Bentinck’s Brigade held the ground around Elviña, with Manningham’s Brigade on its left and Warde’s Guards Brigade in reserve behind; all of Baird’s First Division.

On their left flank, Leith’s brigade held the ground to the Corunna Road, with Hill between the road and the Burgo Estuary and Catlin Craufurd’s Brigade in reserve behind the crest of the ridge; all of Hope’s Second Division.

Map of the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

A mile to the north of Elviña, Paget’s Reserve Division held the village of Oza, with Fraser’s Division ½ mile to the west of Oza; these formations protecting Moore’s right flank and the approach to Corunna from the west.

The fighting began on 15th January 1809, on the Heights of Palavea, running parallel to the Monte Mero ridge ¾ mile to its south, as the infantry of Merle and Mermet’s Divisions, supported by Lorge’s and La Houssaye’s dragoons moved onto the heights, to push back the British advanced piquets.

A brisk fight developed between 3 companies of French Voltigeurs, supported by horse artillery and the British 5th Foot.

26th Foot at the Battle of Corunna on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

In attempting to capture the French guns, the British were surprised by the Voltigeurs, firing from behind a wall, the 5th Foot losing their colonel and forced back with heavy casualties.

All along the heights, the British advanced parties were driven back and the Heights of Palavea and Peñasquedo occupied by the French divisions of Merle and Mermet, joined the next afternoon by Delaborde’s Division.

10 heavy French guns took post on the Heights of Peñasquedo, ready to bombard the village of Elviña in support of Merle.

On 16th January 1809, Marshal Soult surveyed the battlefield from the Heights of Palavea/Peñasquedo.

Soult could see, positioned facing the French on the slopes of Monte Mero, the lines of Baird’s First Division and much of Hope’s Second Division.

Catlin Craufurd’s Brigade was out of sight behind the crest of Monte Mero. Paget’s Reserve Division and Fraser’s Third Division were in the distance and probably invisible.

The French army was drawn up with La Houssaye’s Dragoon Division on the extreme left, Mermet’s Infantry Division facing Elviña, supported by the 10 heavy guns, Merle’s Infantry Division in the centre and Delaborde’s Infantry Division forming on the right.

Sir John Moore encouraging the Black Watch at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

Half of Lorge’s Dragoon Division stood behind the French right, on the estuary coast, with the other half detached on the far bank of the Burgo Estuary.

Fortescue remarks on Soult the contrast between his considerable strategic flair and his lack of resolution in the face of battle.

Soult’s indecision showed on the 16th January 1809, the French army waiting for the order to attack, the opportunity to capture a significant number of British troops ebbing with the loading of Moore’s ships.

At 1.30pm, Moore commented that his army could be away within a few hours, but Soult had just given the order to attack, Mermet on the left, Merle in the centre and Delaborde on the right.

General of Brigade Jardon led the attack on Elviña with a mass of 500 Voltigeurs.

Bentinck’s Brigade was formed with the 4th King’s Own on the right, the 50th on the hillside above Elviña and the 42nd Black Watch on the left.

Jardon advanced into Elviña, driving the British piquets out of the village, the French heavy guns firing on the British lines on the hillside, while the main body of Mermet’s Division attacked from the Heights of Peñasquedo at the run, the French 47th Regiment advancing to the west of Elviña, the French 31st Regiment penetrating into Elviña and advancing round the eastern side of the village

It was a feature of Moore’s generalship that he exercised close supervision at points of crisis, as did Wellington.

It is reported that the British troops, about to be attacked at Elviña and unsettled by the French heavy gun fire, murmured along the ranks ‘Where is the general?’ They meant Moore.

42nd Highlanders the Black Watch at the Battle of Corunna on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Harry Payne

They were not disappointed. Moore galloped up and, after a brief visit to the brigades on the British left flank, returned to supervise the deployment of the British battalions around Elviña.

Moore directed Charles Napier, commanding the 50th Regiment, to reinforce the piquets in Elviña.

To counter the threat to outflank the British line on the right, Moore ordered the 4th King’s Own to bring its right wing back at a right angle and sent orders to General Paget to bring his division up on the flank.

Moore appears to have directed the battle on the right flank from near its beginning, General Baird being at some stage struck by a cannon ball and disabled.

1st Foot Guards at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Reginald Wymer

One column of the French 31st Regiment halted to deploy on the eastern side of Elviña and the 42nd Black Watch were ordered by Moore to attack them.

The 42nd advanced, fired a volley and charged the French 31st, driving them back to the bottom of the hill, where the 42nd halted behind a wall.

Soon afterwards, the second column of the French 31st emerged from the northern end of Elviña and were charged by the 50th Regiment, as the French attempted to form up after their advance through the village.

The 50th drove the French infantry back through the village in extremely heavy fighting, a detachment of Voltigeurs being captured after attempting to hold the village church.

Colonel Charles Napier defended by Drummer Guibert at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by R. Granville-Baker

Napier took his 50th Regiment through Elviña and was forming to continue his attack. Instead of reinforcing the 50th, Bentinck withdrew the British troops still in Elviña, leaving Napier to be counter-attacked by Mermet’s reserves and his battalion driven back, Napier being severely wounded captured and his major killed.

Meanwhile, Moore brought up the two battalions of the 1st Guards and launched one battalion in an attack on the French centre.

As the Guards advanced, the 42nd Highlanders began to withdraw, compelling Moore to lead them back into the line in person.

As he led the Black Watch forward, Moore was struck by a roundshot fired by the French guns on the Heights of Peñasquedo and thrown from his horse, his left arm nearly severed and his chest and lungs severely damaged.

Moore was placed by a bank before being carried to the rear, while an officer rode off to find General Hope and inform him that he was now in command, both Moore and Baird being wounded.

The fatally wounded Sir John Moore is carried from the field at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Henri Dupray

In the meantime, there was no senior officer to direct the British right wing.

The French pursued the 50th Regiment through Elviña and were only halted by the second battalion of the 1st Guards and driven back into the village.

Darkness was falling and both sides in the area of Elviña, now exhausted, withdrew from the village.

While the fighting around Elviña was taking place, on the extreme left of the French attack, the 4 battalions of the French 47th Regiment enveloped the British 4th King’s Own on the right flank of Moore’s line.

The 4th, from positions behind a wall, held the French attack until Paget’s Division came up to relieve them, the 91st and 20th Regiments advancing up the right bank of the River Monelos, while the 52nd Light Infantry and 95th Rifles, with the 28th in support, came straight up the valley and took the French 37th in flank, forcing the French regiment to retreat.

95th Rifles: Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

Two of La Houssaye’s dragoon regiments twice attempted to charge the 95th Rifles, but were driven back by the difficulty of the ground and the steady fire of the 95th.

Paget seems to have halted level with the rest of the British line, although the 95th may have attempted, unsuccessfully, to storm the French guns.

It is claimed that the 95th Rifles took 150 prisoners during their attack.

3rd Battalion Royal Scots at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

Merle’s French Division, in the centre, began an attack on the 42nd as the Highlanders advanced, but were in turn taken in flank by Manningham’s Brigade.

Merle turned to deal with Manningham and the two forces spent the rest of the day in a furious combat, which engulfed Leith’s Brigade and only petered out with the fall of darkness.

On the French right, General Foy of Delaborde’s Division began his attack on the village of Piedralonga, overlooking the Burgo Estuary, late in the afternoon.

The British 14th and 92nd Regiments contested the village, the combat swaying backwards and forwards, until it also petered out with the fall of darkness, neither side having gained much of an advantage.

At around 6pm, the fighting ended all along the line.

It is conjectured that if Moore had not been fatally injured, he might well have developed the attack by Paget’s Reserve Division, enveloping Soult’s left wing and possibly capturing the French guns on the Heights of Peñasquedo.

Corunna from the south-west: Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

As it was, Hope decided to end the contact with the French army and hurry the evacuation of the army onto the British transports.

After consultations with Royal Navy senior officers, the army began its withdrawal from Monte Mero at 9pm, leaving their camp fires burning and marching down to Corunna, to be taken onto the ships.

The embarkation continued through the night and, at dawn, the last piquets fell back from the countryside surrounding Corunna to go on board.

With daybreak on 17th January 1809, the French discovered the absence of the British troops and advanced onto the Heights of Santa Margarita, overlooking Corunna and opened fire.

This fire interrupted the ceremony taking place in a bastion of the citadel. A party of soldiers from the 9th Foot, with a chaplain and 4 officers, Anderson, Colborne, Stanhope and Percy, were carrying the body of Sir John Moore to a newly dug grave.

The burial was hurried by the French gunfire opening on the British fleet.

Hill’s Brigade, the covering force, was taken on board and the fleet sailed for England.

42nd Black Watch attack Elviña at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Cecil Doughty

Casualties at the Battle of Corunna:

The British casualties during the retreat to Corunna were around 4,000 men killed, wounded and captured, of whom 800 to 900 were casualties at the Battle of Corunna.

General Service Medal with clasp for the Battle of Corunna on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

The British regiments that suffered the heaviest casualties in the Battle of Corunna were:

50th Foot; with 5 officers and 180 men as casualties

42nd Black Watch; with 6 officers and 140 men as casualties

81st Foot; with 11 officer and 139 men as casualties

These regiments suffered particularly from the fire of the 10 French guns positioned on the Heights of Peñasquedo, to which there was no British reply.

The French casualties at the battle were around 900 men killed, wounded and captured.

The 31st Light of Mermet’s Division lost 330 killed, wounded and captured.

Medal and Battle Honour for the Battle of Corunna:

The Military General Service Medal 1848 was issued to all those serving in the British Army present at specified battles during the period 1793 to 1840 who were still alive in 1847 and applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one or more of the clasps. There were 21 clasps available for service in the Peninsular War.

The Battle of Corunna was one of the clasps.

The battle honour ‘Corunna’ was awarded to the following regiments: 1st Guards, 1st Royal Scots, 2nd Queen’s, 4th King’s Own, 5th, 6th, 9th, 14th, 20th, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 26th, 28th, 32nd, 36th, 38th, 42nd Black Watch, 43rd Light Infantry, 50th, 51st, 52nd Light Infantry, 59th, 71st, 76th, 79th, 81st(with distinction), 82nd, 91st and 95th Rifles.

Gold Medal awarded to Sir John Moore for the Battle of Corunna on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

Army Gold Medal:

In 1810 a Gold Medal was issued to be awarded to officers of rank of major and above for meritorious service at certain battles in the Peninsular War, with clasps for additional battles. The ‘Large Gold Medal’ was awarded to generals, the ‘Small Gold Medal’ to majors and colonels, with the medal replaced by a cross where four clasps were earned. The Battle of Corunna was one of the battles. The medal was awarded posthumously to Sir John Moore.

Follow-up to the Battle of Corunna:

The British army arrived in England in a terrible state. But by May 1809, it was back in Portugal, under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington. The British army finally left the Peninsular in 1814, over the Pyrenees Mountains into France.

There is controversy as to what Moore achieved in his 1808/9 campaign. Fortescue takes the view that Moore’s advance into Central Spain disrupted the French plans to advance into Portugal and capture Lisbon, leaving the Portuguese capital available as the main base for Sir Arthur Wellesley’s return to the Peninsular in May 1809, a crucial advantage.

Medal issued privately to commemorate the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Corunna:

- Charles Napier, commanding the British 50th Foot, was severely wounded and captured during the counter-attack by the French 31st Regiment outside Elviña. Napier was protected by a French drummer called Guibert against his aggressive comrades. Marshal Soult ensured that Napier was nursed back to health and conveyed to Britain to convalesce by Marshal Ney. Napier returned to serve under Wellington in the Peninsular in 1810.

- The French General Jardon: Fortescue describes Jardon as ‘a crabbed, foul-mouthed, hard-drinking old soldier, who talked the French of the canteen and could hardly write his name.

General of Brigade Henri-Antoine Jardon: Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

Though a general, he never encumbered himself with aide-de-camp, servant, horses or baggage, but marched on foot with the advanced guard…. In action he carried a musket among the foremost of the skirmishers, and, so long as he could burn powder, was perfectly happy. Such was the ‘Voltigeur General,’ brave as a lion and a born fighting man….’ Jardon was killed in battle later in the 1809 fighting against the Portuguese.

- In contrast to the accounts of drunkenness and indiscipline during the retreat to Corunna, there are stories of gallantry and hardihood. Sergeant William Newman of the 43rd Light Infantry gathered a party of soldiers who were trudging across a field and fought off an attack by French cavalry. He was commissioned for this feat.

- The French commander, Marshal Soult, erected a memorial to Sir John Moore in the Citadel at La Coruña, which stated: ‘JOHN MOORE LEADER OF THE ENGLISH ARMIES IN SPAIN SLAIN IN BATTLE 1809’.

- Charles Wolfe wrote this poem entitled: “The burial of Sir John Moore at Corunna”.

The fatal wounding of Sir John Moore at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 17th January 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by T Sutherland

Not a drum was heard, not a funeral note,

As his corse to the rampart we hurried;

Not a soldier discharged his farewell shot

O’er the grave where our hero we buried.

We buried him darkly at dead of night,

The sods with our bayonets turning,

By the struggling moonbeam’s misty light

And the lanthorn dimly burning.

Burial of Sir John Moore at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 18th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

No useless coffin enclosed his breast,

Not in sheet or in shroud we wound him;

But he lay like a warrior taking his rest

With his martial cloak around him.

Few and short were the prayers we said,

And we spoke not a word of sorrow;

But we steadfastly gazed on the face that was dead,

And we bitterly thought of the morrow.

Medal commemorating the death of Sir John Moore at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 16th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

We thought, as we hollow’d his narrow bed

And smooth’d down his lonely pillow,

That the foe and the stranger would tread o’er his head,

And we far away on the billow!

Lightly they’ll talk of the spirit that ‘s gone,

And o’er his cold ashes upbraid him—

But little he’ll reck, if they let him sleep on

In the grave where a Briton has laid him.

But half of our heavy task was done

When the clock struck the hour for retiring;

And we heard the distant and random gun

That the foe was sullenly firing.

Slowly and sadly we laid him down,

From the field of his fame fresh and gory;

We carved not a line, and we raised not a stone,

But we left him alone with his glory

Burial of Sir John Moore at the Battle of Corunna, also known as the Battle of Elviña, on 18th January 1809 in the Peninsular War

References for the Battle of Corunna:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Cacabelos

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of the Douro

Podcast of the Battle of Corunna: The battle, also known as the Battle of Elviña, that ensured the escape of the British army from Spain on 16thJanuary 1809, during the Peninsular War, with the death of Sir John Moore at the moment of success: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcasts.