This battle, also known as the Second Battle of Oporto, saw Sir Arthur Wellesley’s (later the Duke of Wellington) successful passage of the River Douro at Oporto in Portugal, on 12th May 1809 during the Peninsular War, forcing Marshal Soult’s French army into headlong and disastrous retreat to Spain

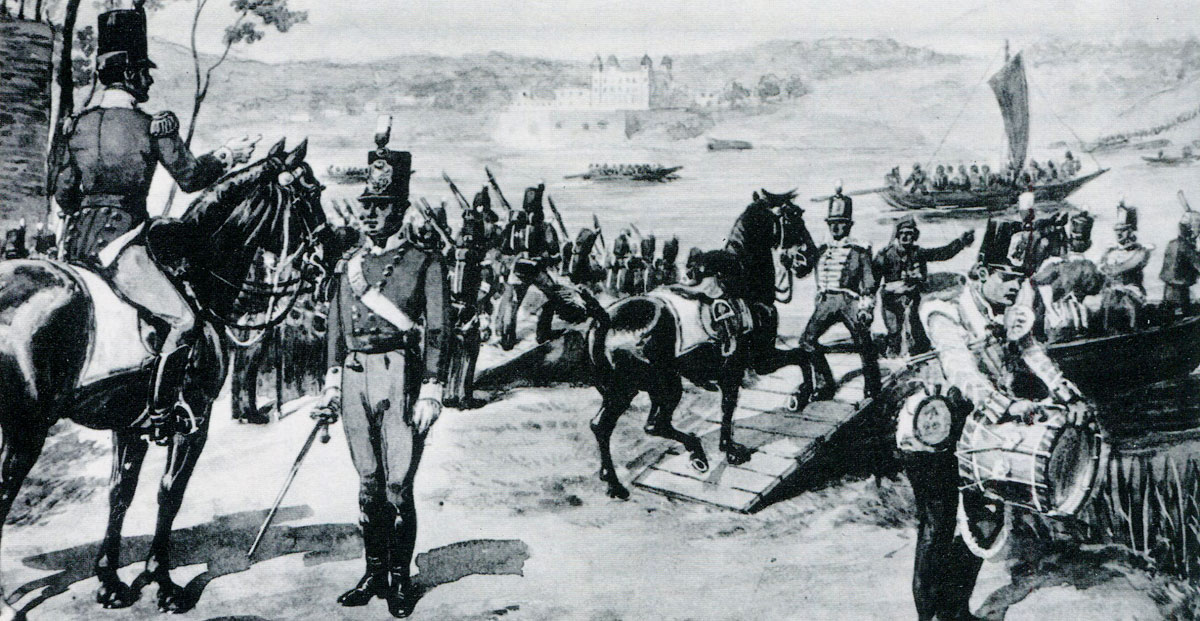

Sir Arthur Wellesley landing at Lisbon before the Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

Podcast of the Battle of the Crossing of the Douro: The battle, also known as the Second Battle of Oporto, that saw Sir Arthur Wellesley’s (later the Duke of Wellington) successful passage of the River Douro at Oporto in Portugal, on 12th May 1809 during the Peninsular War, forcing Marshal Soult’s French army into headlong and disastrous retreat to Spain: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Podcast of the Battle of the Crossing of the Douro: The battle, also known as the Second Battle of Oporto, that saw Sir Arthur Wellesley’s (later the Duke of Wellington) successful passage of the River Douro at Oporto in Portugal, on 12th May 1809 during the Peninsular War, forcing Marshal Soult’s French army into headlong and disastrous retreat to Spain: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Corunna

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Talavera

Marshal Soult French commander at the Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

Battle: Passage of the Douro

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of the Douro: 12th May 1809

Place of the Battle of the Douro: At Oporto in Northern Portugal

Combatants at the Battle of the Douro: British and Portuguese against the French

Generals at the Battle of the Douro: Major General Sir Arthur Wellesley, commanding the British and Portuguese army against Marshal Soult commanding the French army.

Size of the armies at the Battle of the Douro: The British and Portuguese army comprised 18,000 troops and 24 guns.

The French army comprised 20,000 troops, 2/3 of whom were with Marshal Soult in Oporto, the rest being with General Loison.

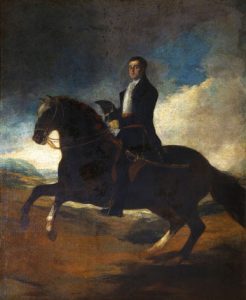

Sir Arthur Wellesley British commander at the Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Goya

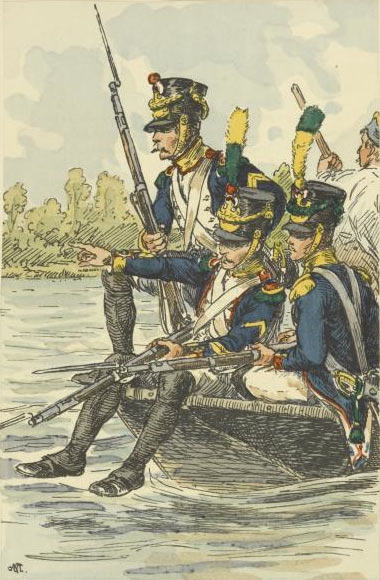

Uniforms, arms and equipment: Uniforms, arms, equipment and training at the Battle of the Douro:

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers, and stovepipe shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments wore dark green jackets.

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

Highland regiments wore the kilt with red tunics and black ostrich feather caps.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light cavalry was increasingly adopting hussar uniforms, with some regiments changing their titles from ‘light dragoons’ to ‘hussars’.

The King’s German Legion (KGL) was the Hanoverian army in exile. The KGL owed its allegiance to King George III of Great Britain, as the Elector of Hanover, and fought with the British army. The KGL comprised both cavalry and infantry regiments. KGL uniforms mirrored the British.

The Portuguese army uniforms increasingly during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe, and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms like the infantry, the horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket. The musket could be fired at three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for a hundred metres or so. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, which fitted the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, and a sword bayonet.

French Cuirassier: Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Hippolyte Belange

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who invented it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was never able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create his powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns with the speed of the French columns of infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

Marshal Soult at the First Battle of Oporto: Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

Winner of the Battle of the Douro: The British and Portuguese.

British Infantry Officer: Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

British order of battle at the Battle of the Douro:

British order of battle at the Battle of the Douro:

Commander: Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Wellesley

Cavalry Division: commanded by Major General Sir Stapleton Cotton

14th Light Dragoons (with 1 troop 3rd Light Dragoons, King’s German Legion), 16th Light Dragoons, 20th Light Dragoons

Sherbrooke’s Division

Guard’s Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General F. Campbell

1st Battalion Coldstream Guards, 1st/3rd Guards, 1 Company of 5th/60th Foot

5th Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General A. Campbell

2nd/7th Royal Fusiliers, 2nd/53rd Foot, 1 Company of 5th/60th Foot, 1st/10th Portuguese Foot

4th Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Sontag

2nd Bn. Detachments, 97th Foot, 1 Company of 5th/60th Foot, 2nd/16th Portuguese Foot

Paget’s Division

6th Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Stewart

29th, 1st Batt. Detachments, 1st/16th Portuguese

7th Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General John Murray

1st Line, KGL, 2nd Line, KGL, 5th Line, KGL, 7th Line, KGL, 1st and 2nd Light Battalions, KGL

Hill’s Division

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Rowland Hill

1st/3rd Buffs, 2nd/48th Foot, 2nd/66th Foot, 1 Company of 5th/60th Foot

7th Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Cameron

2nd/9th Foot, 2nd/83rd Foot, 1 Company of 5th/60th Foot, 1st/16th Portuguese Foot

Artillery: commanded by Colonel Howarth

Lawson’s battery (light 3 pdrs), Lane’s Battery (light 6 pdrs) and Baynes’ Battery (light 6 pdrs) detached

Rettberg’s Battery (light 6 pdrs) and Heise’s Battery (light 6 pdrs)

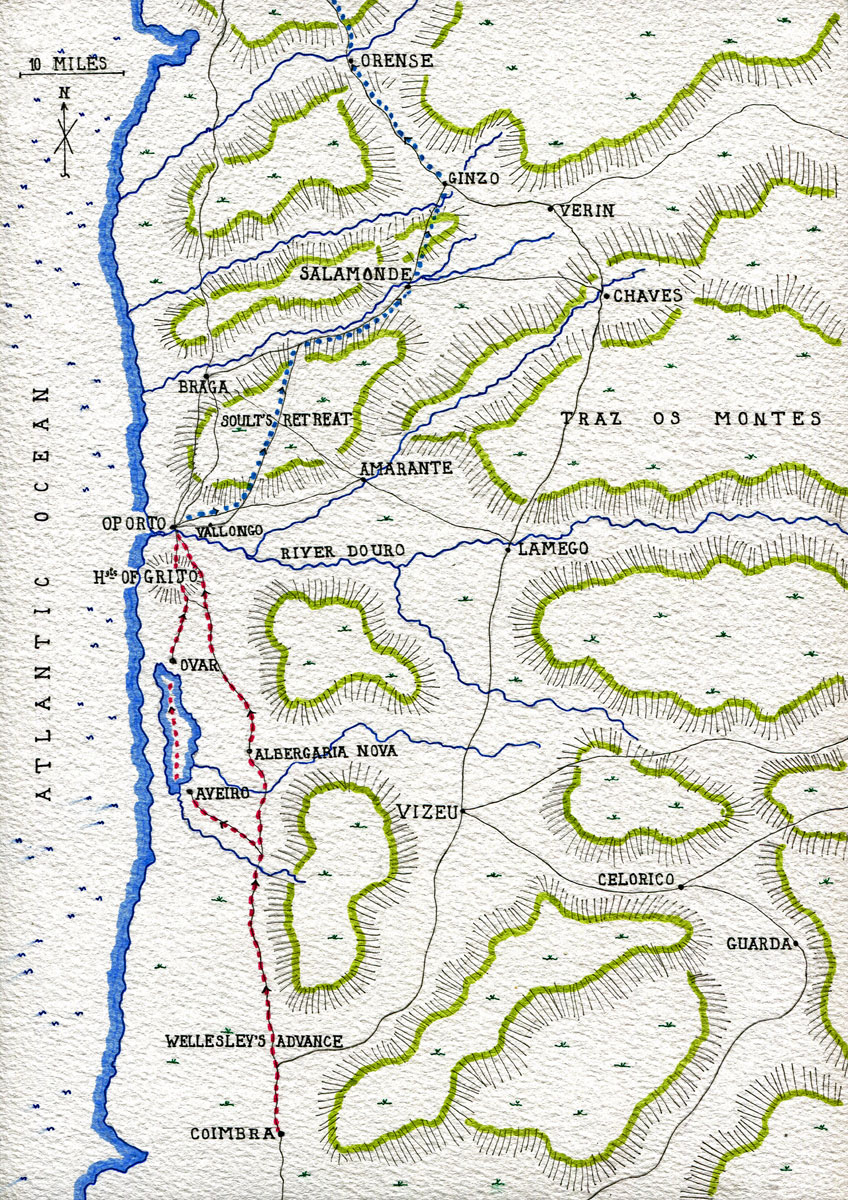

Map of Central Portugal: Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

Background to the Battle of the Douro:

Following the evacuation of the British army from Corunna to England and the death of Sir John Moore on 16th January 1809, a small British force remained in Lisbon.

On 22nd April 1809, Sir Arthur Wellesley, vindicated by the official enquiry into the Convention of Cintra, following the Battle of Vimeiro, arrived in Lisbon and, 2 days later, took over command of the British army in the Portuguese capital from Sir John Craddock.

Wellesley was immediately concerned with two French armies: Marshal Victor’s army at Merida in Spain, near the Portuguese border at Badajoz and Marshal Soult’s army, occupying the northern Portuguese city of Oporto, on the north bank of the River Douro.

Wellesley decided to attack Soult, while leaving a force in Lisbon to confront Victor, should he advance into Southern Portugal.

On 27th April 1809, Wellesley gave orders for the concentration at Coimbra, half-way between Lisbon and Oporto, between 30th April and 4th May 1809, of 1 brigade of cavalry, 8 brigades of infantry, 5 batteries of artillery and 6,000 Portuguese troops.

On 4th May 1809, Wellesley reached Coimbra, where he reorganised his army.

News reached Wellesley on that day that the Portuguese commander Silveira had been defeated, ruling out, for the moment, the cutting of Soult’s line of retreat through Amarante, east of Oporto.

Wellesley despatched Beresford, the new British commander of the Portuguese army, on 6th May 1809, to join Silveira at Lamego, with instructions to prevent Soult from crossing the River Douro and marching east, once defeated by Wellesley’s army.

On 6th May 1809, Wellesley met with a French officer, Captain Argenton, who was masterminding a conspiracy against Soult. Argenton had little to say that was of interest to Wellesley and was sent on his way, with precautions taken to avoid him seeing the size or preparations of the army.

On the following day, Wellesley’s advanced guard marched north from Coimbra towards Oporto.

Oporto, with the Seminary on the left and the Convent on the right of the river: Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Robert Batty

Podcast of the Battle of the Crossing of the Douro: The battle, also known as the Second Battle of Oporto, that saw Sir Arthur Wellesley’s (later the Duke of Wellington) successful passage of the River Douro at Oporto in Portugal, on 12th May 1809 during the Peninsular War, forcing Marshal Soult’s French army into headlong and disastrous retreat to Spain: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Podcast of the Battle of the Crossing of the Douro: The battle, also known as the Second Battle of Oporto, that saw Sir Arthur Wellesley’s (later the Duke of Wellington) successful passage of the River Douro at Oporto in Portugal, on 12th May 1809 during the Peninsular War, forcing Marshal Soult’s French army into headlong and disastrous retreat to Spain: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

The advanced guard paused on 8th May 1809 and continued its march the next day, followed by Cotton’s cavalry and Stewart’s and Murray’s infantry brigades, with the aim of taking Franceschi’s dragoon division by surprise at Albergaria Nova, just beyond the halfway point to Oporto.

In the meantime, Hill’s Brigade, marching on a more western route and conveyed by boats through the marshland between Avero and Ovar, was to surprise the French further north on the main Oporto road, after which, Hill was to combine with Cotton and storm the main bridge across the River Douro opposite the city of Oporto.

Cotton’s cavalry arrived at Albergaria Nova at dawn on 10th May 1809.

The French cavalry under Franceschi appeared to be taken by surprise, but being supported by a regiment of infantry and a battery of horse artillery, Cotton was deterred from an attack, until his supporting infantry came up.

Due to difficulties suffered by Stewart’s Brigade with its artillery transport, the first troops to come up with Cotton’s cavalry were Trant’s Portuguese troops.

On seeing the Portuguese, Franceschi withdrew northwards, leaving 2 squadrons of cavalry to cover his retreat. These 2 squadrons were charged by the 16th Light Dragoons, but escaped with little loss.

The British halted at Oliveira, leaving Franceschi free to continue his march and join Mermet’s infantry division on the Heights of Grijo.

Hill arrived at Ovar by boat, but found that Franceschi was formed up on the road and not susceptible to attack.

Mermet sent a force to confront Hill and some skirmishing took place, until Franceschi retired and Cotton’s cavalry came up, at which the French infantry also fell back to the Heights of Grijo.

Battle of Grijo: Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by JJ Jenkins

Battle of Grijo

Wellesley now had 1,500 cavalry and 7,000 infantry, comprising Paget’s Division and Hill’s Brigade, facing the French force at Grijo, of 1,200 cavalry and 4,000 infantry.

In the early hours of 11th May 1809, Hill’s Brigade marched north up the main road to Oporto, past the French positions to the west of the road, while Wellesley advanced to the attack against the French situated on the Heights of Grijo.

Wellesley’s attack was made in the afternoon of 11th May, by the light companies of Stewart’s Brigade (from 29th, 43rd and 52nd Regiments), but they came up against stiff resistance and could make little headway against the French.

Wellesley despatched the 16th Portuguese Regiment to outflank the French on the left and the King’s German Legion around the right flank, while the remainder of Stewart’s Brigade and the cavalry reinforced the attack by the light companies.

Officer of the French 31st Light Infantry: Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

Merlet reacted promptly, beginning a hasty retreat, with the 31st Light Infantry acting as rear-guard.

Wellesley permitted his adjutant-general, Charles Stewart, to attack the French rear-guard with 2 squadrons of cavalry, one from each of the 16th and 20th Light Dragoons.

Stewart’s dragoons advanced in single file along a narrow lane and, on coming up with the French rear-guard, charged them, at which the French troops took to their heels.

Around 100 of the French light infantrymen were taken prisoner, the remainder escaping.

Hill’s attempt to cut off the French retreat from the Heights of Grijo came to nothing as Hill’s approach route became muddled with Trant’s, delaying both forces and permitting the French to pass through and cross the River Douro into Oporto.

Once the divisions of Mermet and Franceschi were across the river, Soult ordered the bridge of boats to be destroyed.

The British force spent the night of 11th May 1809 in the French tents erected on the Heights of Grijo.

British and Portuguese casualties in the battle were a little over 100 men, while the French casualties were around 200.

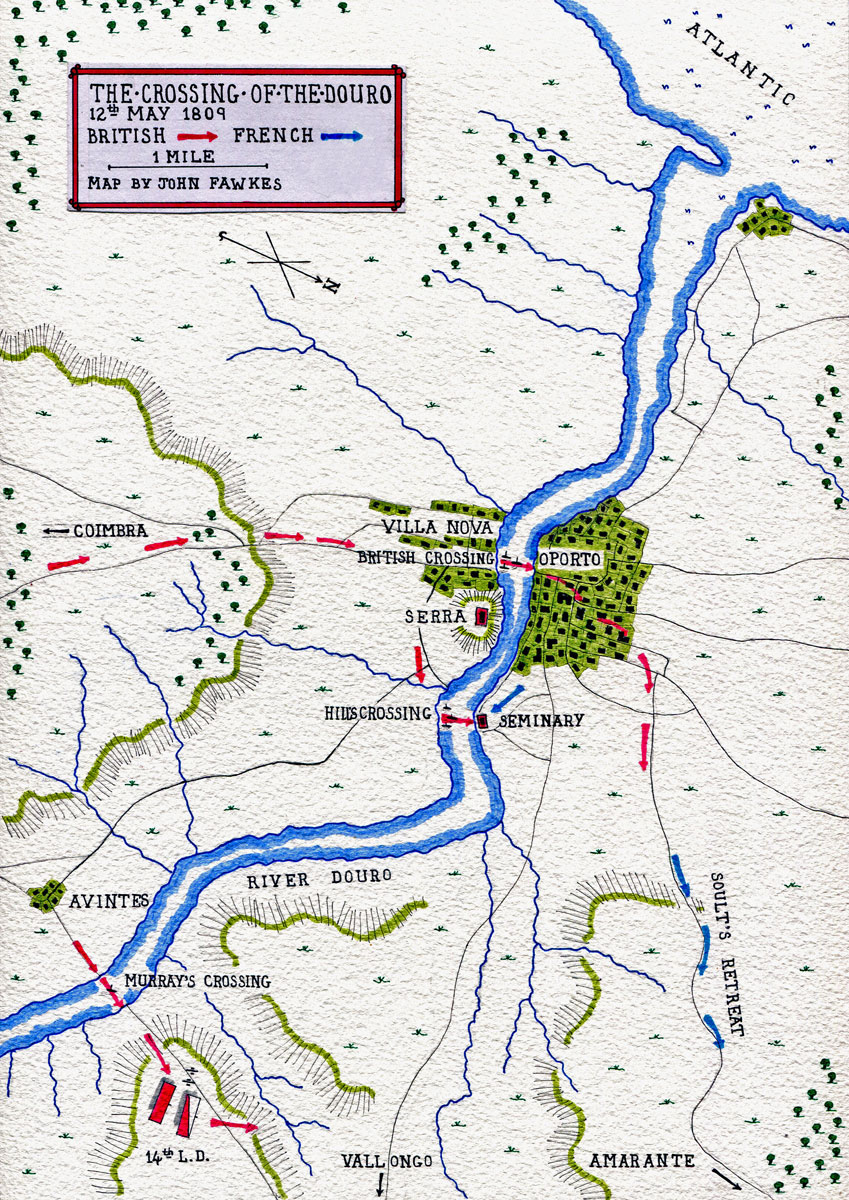

Map of the Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

Crossing of the River Douro

Argenton, the leader of the conspiracy against Soult who had met with Wellesley, was reported to Soult by one of the officers Argenton attempted to suborn. Against an offer of amnesty, Argenton told Soult all he knew. This was enough to warn Soult that Wellesley was advancing on him with a stronger army than his own and that he must retreat to Spain through the Traz-os-Montes mountain range with all haste.

The first step was to order General Loison to hold the bridge across the River Tamega, a tributary of the Douro, at Amarante, at all costs.

As it was clear that his army would have to stay in Oporto until the 12th May 1809, Soult ordered all the boats on the Douro in the vicinity of Oporto to be moved to the north bank, to remove from Wellesley the means of crossing the river.

Soult ordered his cavalry to patrol the area between Oporto and the sea, in case Hill’s Brigade brought the boats they had used on their journey up the coast from Avero to Ovar to cross the estuary.

Soult lodged his 11,000 infantry in the city in good quarters and took up residence in a house looking out to the west of Oporto.

Oporto, with the Seminary on the right: Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Robert Batty

It is clear that Soult’s focus was on the area between Oporto and the Atlantic Ocean, neglecting the river upstream of the city.

At 2am on 12th May 1809, a loud explosion announced the destruction of the bridge of boats across the River Douro opposite the centre of Oporto.

Wellesley’s army, woken by the explosion, paraded and marched to Villa Nova, a suburb of the city on the south bank of the Douro, where they occupied the narrow streets and massed behind the Serra Convent, positioned on a hill overlooking the river at the eastern end of the town.

Soult, looking to the west, seemed unaware of the presence of Wellesley’s army in Villa Nova.

Mermet’s Division left the city escorting the sick and wounded and the reserve artillery, marching along the road heading east towards Amarante.

On the north bank of the River Douro, standing apart from and to the east of the city, was the Bishop’s Seminary, a large unfinished building, surrounded by a high square wall.

A gate in the north wall of the Seminary opened onto a path to the Vallongo Road, heading east from Oporto.

The Serra Convent overlooked the Seminary from the south bank of the River Douro, enabling the British to see that there were no French troops in the area of the Seminary and to bring guns to bear on the north bank.

The point at which the Buffs crossed the River Douro: Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

One of the British officers searching for boats with which to cross the river, Colonel Waters, was pointed by Portuguese residents to 4 large unguarded barges, moored on the north bank.

Waters crossed the river with some of the Portuguese in a skiff and brought the 4 barges back to the south bank, without being observed by the French.

On his journey to the north bank, Waters conducted a cursory inspection of the Seminary, confirming it to be unoccupied by any French troops.

Waters reported to Wellington who commented ‘Well, let the men cross.’

Crossing the River Douro at the Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

The 3rd Regiment, the Buffs, were transported across the River Douro in the 4 barges, a company at a time, occupying the Seminary, closing the gate in the north wall and fortifying the perimeter wall.

On the third trip across the river, shots were fired by the French who had woken up to the movement of redcoats.

Sir Arthur Wellesley watching his troops crossing the river at the Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

Earlier, several officers of Mermet’s Division, marching along the road to Vallongo, noticed the traffic on the river and reported it to Mermet, who refused to credit the reports and continued on his march to the east, without taking any action.

General Foy, riding along the river at around 10.30am, was informed that the British were crossing the river and rode off to position a battery on the heights overlooking the Seminary and bring up the nearest French regiment, the 17th Light, to attack the Seminary and drive out the British troops.

Foy sent a staff officer to report the British crossing to Soult, who ordered Foy to hold the eastern corner of the city until Soult could bring up a force to drive the British back into the river.

At around 11.30am, the 17th was able to begin its attack on the Buffs in the Seminary and French guns came down to the bank of the river to fire on the barges that were continuing to bring British infantry across.

The British guns positioned around the Serra Convent opened fire on the French guns from their elevated position and, firing shrapnel, quickly disabled many of the French gunners and horses and the infantry attacking the Seminary, driving the French to take cover in the neighbouring buildings.

In addition, the British infantry, firing from their positions on the Seminary walls, took a heavy toll of the French infantry attempting to storm the compound.

Wounding of General Edward Paget during the Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by R. Westall

General Paget, supervising the operation on the north bank, was disabled by a severe arm injury, leaving General Hill in command.

All the while the 4 barges were plying across the river, rowed by British troops and Portuguese civilians, bringing across the 48th and 66th Regiments from Hill’s Brigade, to join their comrades of the Buffs.

General Delaborde took over the French assault on the Seminary, launching the 70th of the Line against the defences, but the 70th was beaten back with considerable loss.

At the beginning of the battle, Regnaud’s Brigade was stationed on the Oporto waterfront, keeping the city’s population away from the river.

Marshal Soult watches British troops crossing the river during the Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by Wal Paget

Soult directed General Regnaud to take his Brigade and join the attack on the Seminary.

On Regnaud’s departure, the citizens of Oporto launched the boats secured by the French army to the north shore, rowed them across to Wellesley’s waiting troops and brought them back to the city.

The first over the river were Stewart’s Brigade, led by the 29th Regiment, followed by the Foot Guards.

Portuguese cartoon of Soult’s flight from Oporto at the Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

The 29th hurried through the streets of Oporto and out onto the Amarente road to the north-east, where they caught up with the rear of Soult’s retreating army, opening fire on the French troops. In their haste, the French abandoned a full battery of guns to the pursuing British.

The British emerging from Oporto came up on the flank of the French troops attacking the Seminary, who joined their comrades on the road to Amarente.

3rd Buffs crossing the river at the Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

Ordering a full retreat, Marshal Soult positioned a rear guard on the heights along the road, but these troops were soon forced to join their comrades in the hurried march away from Oporto towards the distant Spanish border.

When Wellesley authorised Colonel Waters to begin the transport of Hill’s Brigade across the river, he ordered General Murray to move a further two miles upstream with his 2 squadrons of the 14th Light Dragoons, 2 guns, the 1st Line Battalion of the King’s German Legion and all the KGL riflemen and cross the River Douro at Avintes.

Murray took some time to convey his troops across the Avintes ferry, damaged as it was and marched to the top of a ridge that overlooked the Vallongo and Amarente roads leading to the east and north-east.

The French army, in considerable disorder, was streaming along the roads away from Oporto, beneath Murray’s position on the ridge.

It would seem likely that Wellesley intended Murray to interfere with Soult’s retreat. Murray, however, took no action, looking down from the ridge on the passing French army, which Fortescue describes as being a ‘mere disorderly mob’, apparently without even his guns opening fire.

The French army passed Murray’s position, followed by the first British infantry regiments from Oporto.

General Charles Stewart, the adjutant-general arrived with a message from Wellesley for Murray.

Officers of the 14th Light Dragoons: Battle of the Crossing of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

Stewart, himself a cavalry officer, appropriated one squadron of Murray’s 14th Light Dragoons, led them down onto the road and set off after the French column at the gallop.

For the first two miles Stewart was compelled to force his way through the British infantry, marching in the same direction in pursuit of Soult’s army.

Generals Foy and Delaborde, seeing the cloud of dust in the distance anticipated they were about to be attacked by cavalry and formed the French rear-guard across the road in close formation, placing men behind the walls on either side of the road for some distance.

Stewart led his light dragoons in the charge against the French rear-guard, which broke and fled.

300 French infantrymen were captured by the single squadron of 14th Light Dragoons, which cannot have numbered more than 150 men. From the British squadron, 3 of the 4 officers were wounded, 10 men killed and 11 severely wounded, mostly from the leading troop of 40 men.

With such a haul of prisoners and the number of their own casualties, Stewart’s squadron was forced to await the arrival of the British infantry. The infantry continued the pursuit until nightfall, when Wellesley called a halt.

British casualties at the Battle of the Douro:

British casualties are described by Fortescue as ‘trifling’: 23 soldiers killed, with 3 officers and 95 soldiers wounded.

Regimental casualties:

14th Light Dragoons: 4 officers and 32 soldiers killed and wounded

16th Light Dragoons: 3 officers wounded

20th Light Dragoons: 1 soldier killed

3rd Buffs: 1 officer wounded

29th Foot: 9 soldiers killed and wounded

48th Foot: 1 officer wounded

66th Foot: 38 offices and soldiers killed and wounded

French casualties at the Battle of the Douro were around 300 killed and wounded and another 300 made prisoner, mainly by Stewart’s squadron of the 14th Light Dragoons at the end of the battle.

A further 1,000 French hospital patients were taken prisoner, when Wellesley marched into Oporto.

Follow-up to the Battle of the Douro:

The night of 12th May 1809 was spent bringing British troops, artillery and baggage across the River Douro into Oporto.

Wellesley’s expectation was that Soult would withdraw to Spain by the eastern route.

Murray’s brigade was ordered to march to Vallongo, followed by the rest of the British infantry.

On 12th May 1809, Silveira, the Portuguese commander acting under Beresford, captured the river crossing at Amarente from Loison, thereby blocking the French retreat to the east.

Battle of Salamonde: Battle of the Passage of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War: picture by JJ Jenkins

Battle of Salamonde

On 13th May 1809, Soult destroyed his artillery and stores and began a retreat to the north.

During this retreat, pursued by Wellesley and Beresford, Soult’s army reached the town of Salamonde. The bridge in the town, known as the Ponte Nova, was partially destroyed and held by Portuguese militia.

Soult sent for Major Dulong of the 31st Light Infantry and ordered him to take the bridge.

With volunteers from his regiment, Dulong, under cover of darkness, crept over the remaining beam, surprised the militia and captured the bridge, which was the next morning sufficiently repaired to allow the French army to cross.

In the meantime the French rearguard was attacked by the British Foot Guards and forced back.

During the night the British guns opened fire on the French troops filing across the damaged bridge.

Once morning came it was seen that hundreds of French soldiers had been swept off the bridge into the deep gulley beneath.

Later on 16th May 1809, the French army reached the River Misarella to find the bridge, known as the Saltador, held by Portuguese levies.

Again, Major Dulong was given the task of taking the bridge, which he did, although wounded in the attack.

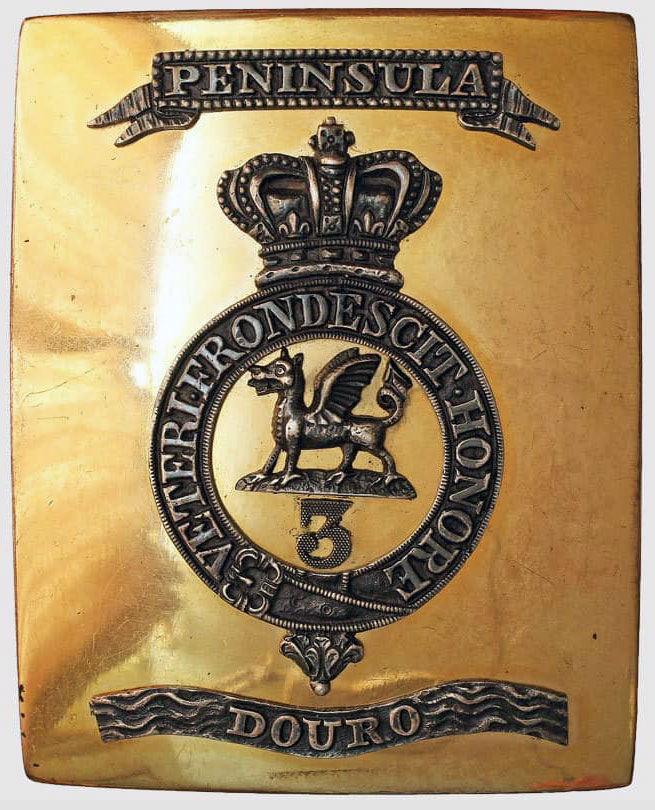

Officer’s Shoulder Belt Plate of the 3rd Buffs commemorating the Battle of the Crossing of the Douro on 12th May 1809 in the Peninsular War

Soult’s army of 20,000 men reached Lugo in Northern Spain on 23rd May 1809, having lost all its guns and equipment and in a state of destitution, suffering 6,000 casualties on the journey. It took many months to recover.

The weather during these operations was atrocious, with almost constant rain for several days.

Medal and Battle Honour for the Battle of the Douro:

The Battle of the Douro was not a clasp on the Military General Service Medal 1848, but is a British battle honour for the following regiments: 14th Light Dragoons, 3rd Buffs, 48th and 66th Regiments.

Anecdote and traditions from the Battle of the Douro:

- Fortescue says of the Battle of the Douro: ‘To effect a surprise in broad daylight; to force the passage of a deep and rapid river in the face of a veteran enemy with, at the outset, no more than a single boat, is an action that demands no ordinary measure of insight, nerve and audacity in a commander’ (Wellesley)…… ‘As to Soult and his officers at large, it can only be said that their carelessness in the matter of watching the river and the boats was extraordinary…..but the truth was that he despised his enemy, as indeed did every one of his brethren and the great Emperor himself, until convinced by bitter experience of the error.’

- One of the steps taken by Wellesley at Coimbra was to attach 1 company of 5th/60th Rifles to each brigade, to strengthen the skirmisher element. Wellesley was fully aware of the part played by Voltigeurs and Tirailleurs in the French attack and how effective they could be against troops standing in formation. Wellesley intended that the British riflemen and battalion light companies should give the French a taste of their own medicine.

- Marshal Soult’s apparent ambition to establish himself as the ruler of Northern Portugal caused a number of French officers under his command to conspire against him. One of these officers, Captain Argenton, met Wellesley twice, the second time during the march to Oporto. On his return, Soult had Argenton arrested and the conspiracy collapsed. Argenton escaped to England, but, on a clandestine visit to his family in France, in December 1809, he was recognised, arrested, tried by court martial and shot.

- The French were taken by surprise by the advance of Wellesley’s army to Oporto. Trant, after visiting the French lines under a flag of truce, reported that the French had no idea of the British being at hand and that they discounted reports that British reinforcements had arrived at Lisbon.

- Sir Arthur Wellesley (the Duke of Wellington) considered the Douro one of his most successful battles and adopted “Douro” as part of his title. He forced a French army, of the same strength as his own, to abandon its strong position behind a river barrier, the Douro and retreat out of Portugal into Spain, losing all its heavy equipment and suffering substantial casualties, with trifling losses to his own troops.

- The Portuguese who brought the boats over the River Douro used to ferry the 3rd Buffs and the rest of the British 4th Brigade, were led by the local barber.

- Lieutenant General Edward Paget, commanding the 2ndDivision, crossed the River Douro with the 3rd Buffs and suffered a severe wound during the French attack on the Seminary, leading to the amputation of his arm.

- The first party of the Buffs across the River Douro comprised 25 soldiers of the Light Company led by Captain Charles Cameron, later to command the battalion. Cameron fought through the Peninsular campaign and was wounded four times.

- Captain Peter Hawker commanded the squadron of the 14th Light Dragoons led by General Stewart in the attack on the rear-guard of Soult’s retreating army, receiving a slight wound. Hawker was severely wounded at the Battle of Talavera and forced to leave the army. Hawker published his journal of the campaign, ‘Journal of a regimental officer during the recent campaign in Portugal and Spain under Lord Viscount Wellington’ and, after leaving the army, wrote books on shooting.

- The Buffs petitioned the Prince Regent to be permitted to emblazon ‘Douro’ on their colours and regimental distinctions. This was finally permitted and was the beginning of the ‘Battle Honours’ system, whereby regiments were permitted to display on their colours the names of specified battles in which they took part.

- Major Dulong, the French officer who forced the bridges at Salamonde and over the River Misarella, with volunteers from his regiment, the 31st Light, served in the French army until 1815, rising to the rank of general, receiving the award of Grand Officer of the Legion d’Honneur, fighting at many battles and being several times wounded.

References for the Battle of the Douro:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Corunna

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Talavera

Podcast of the Battle of the Crossing of the Douro: The battle, also known as the Second Battle of Oporto, that saw Sir Arthur Wellesley’s (later the Duke of Wellington) successful passage of the River Douro at Oporto in Portugal, on 12th May 1809 during the Peninsular War, forcing Marshal Soult’s French army into headlong and disastrous retreat to Spain: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.