the battle fought on 22nd January 1879, where the Zulus wiped out a substantial British force, including the 1st Battalion, 24th Foot and rocked Victorian society

52. Podcast on the Battle of Isandlwana fought on 22nd January 1879; where the Zulus wiped out a substantial British force rocking British Victorian society: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

52. Podcast on the Battle of Isandlwana fought on 22nd January 1879; where the Zulus wiped out a substantial British force rocking British Victorian society: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Kandahar

The next battle of the Zulu War is the Battle of Rorke’s Drift

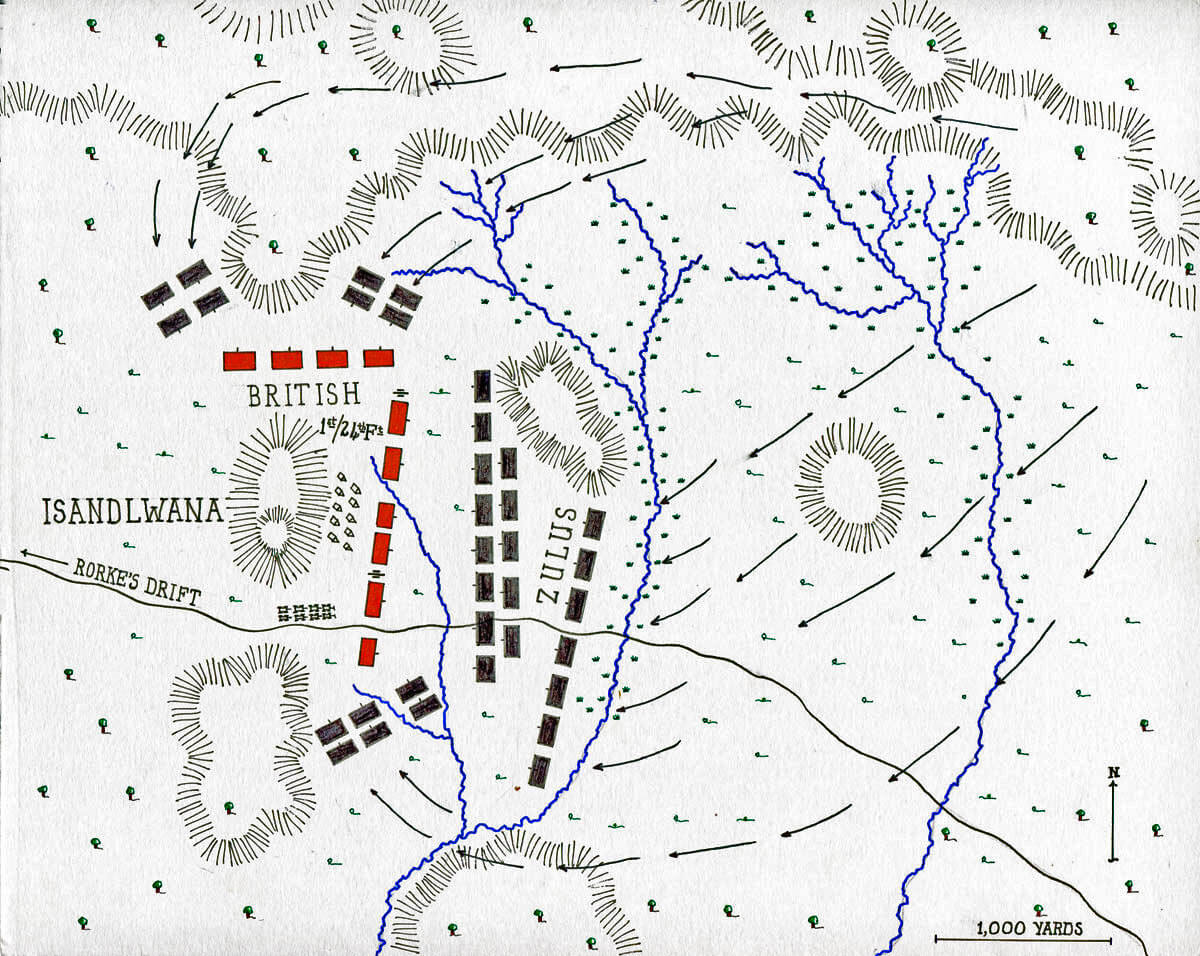

Battle: Isandlwana

War of the Battle of Isandlwana: Zulu War

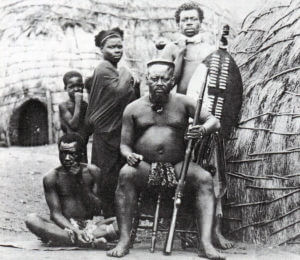

Chiefs Ntshingwayo kaMahole (seated) Zulu commander at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War

Date of the Battle of Isandlwana: 22nd January 1879

Place of the Battle of Isandlwana: 10 miles east of the Buffalo River in Zululand, South Africa.

Combatants at the Battle of Isandlwana: Zulu army against a force of British troops, Natal units and African levies.

Commanders at the Battle of Isandlwana: Lieutenant Colonel Pulleine of the 24th Foot and Lieutenant Colonel Durnford commanded the British force at the battle. The Zulu Army was commanded by Chiefs Ntshingwayo kaMahole and Mavumengwana kaMdlela Ntuli.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Isandlwana: The British force comprised some 1,200 men. It is likely that they were attacked by around 12,000 Zulus.

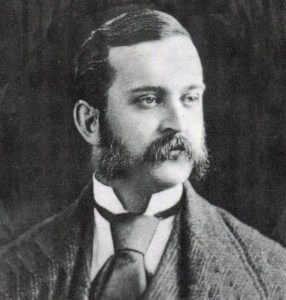

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pulleine, 1st/24th Regiment, British commander killed at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War

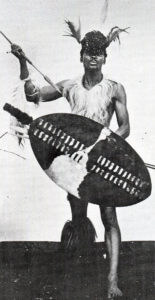

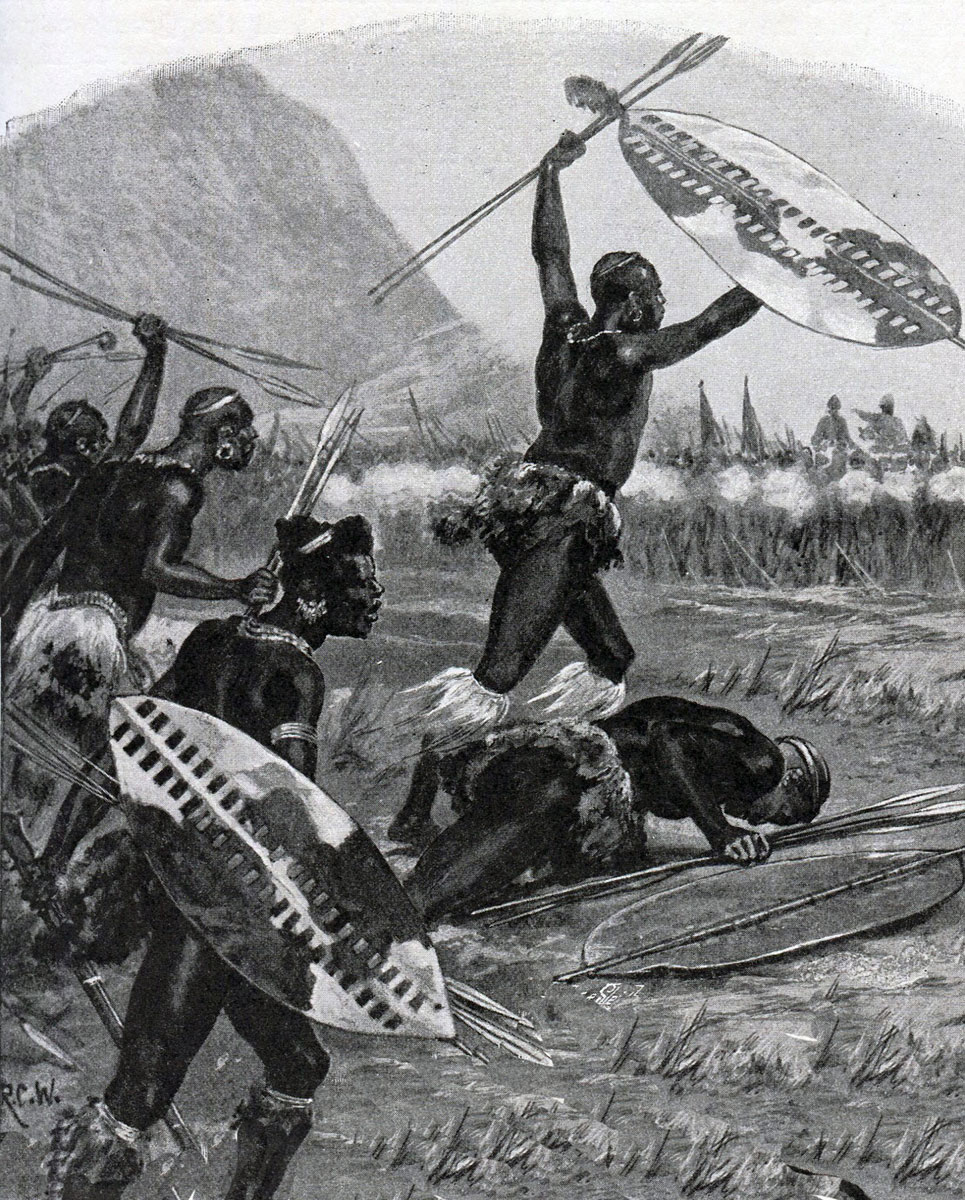

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Isandlwana: The Zulu warriors were formed in regiments by age, their standard equipment the shield and stabbing spear. The formation for their attack, described as the ‘horns of the beast’, was said to have been devised by Shaka, the Zulu King who established Zulu hegemony in Southern Africa. The main body of the army delivered a frontal assault, called the ‘loins’, while the ‘horns’ spread out behind each of the enemy’s flanks and delivered the secondary and often fatal attack in the enemy’s rear. Cetshwayo, the Zulu King, fearing British aggression, took pains to purchase firearms wherever they could be bought. By the outbreak of war, the Zulus had tens of thousands of muskets and rifles, but of a poor standard and the Zulus were ill-trained in their use.

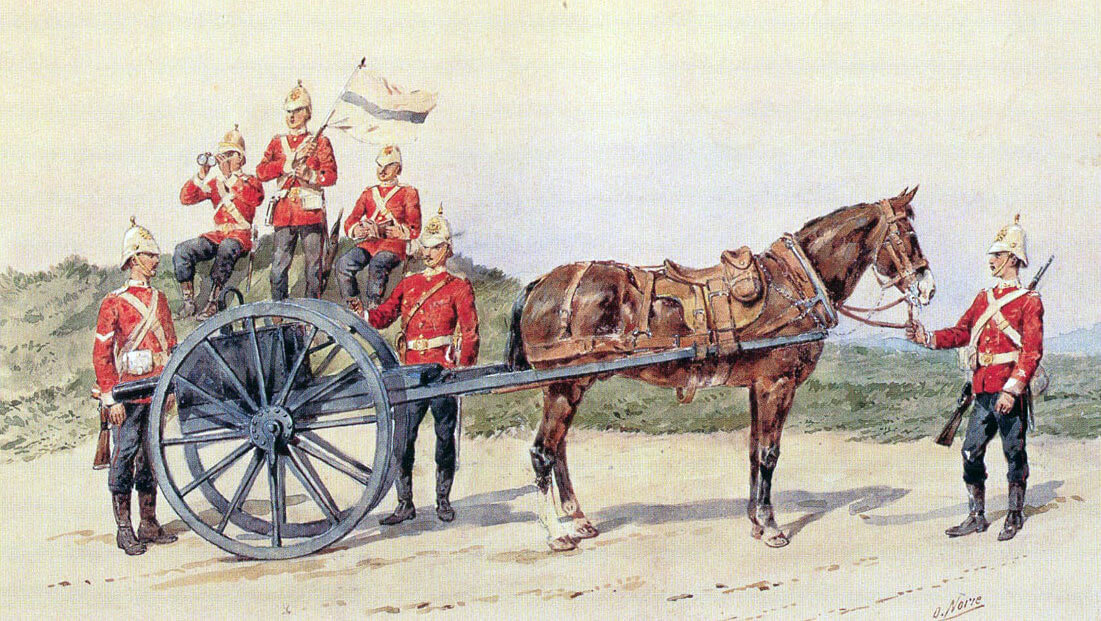

The regular British infantry were equipped with the breach loading single shot Martini-Henry rifle and bayonet. The British infantry wore red tunics, white solar topee helmets and dark blue trousers, with red piping down the side. The irregular mounted units wore blue tunics and slouch hats.

Winner of the Battle of Isandlwana: The British force was wiped out by the Zulu Army.

Zulu attack at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

British Regiments at the Battle of Isandlwana:

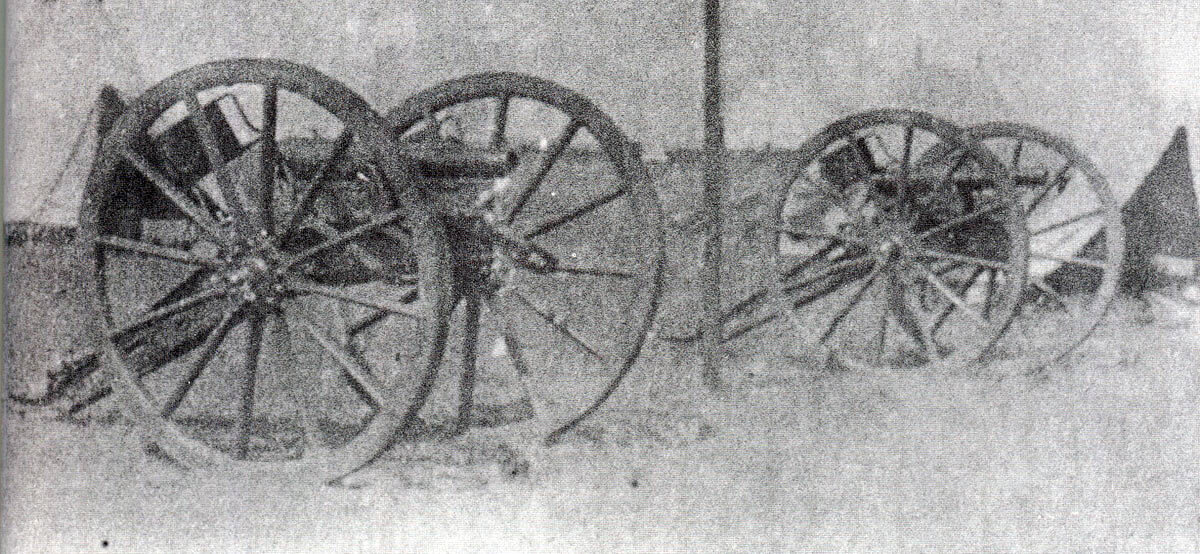

2 guns and 70 men of N Battery, 5th Brigade, Royal Artillery (equipped with 2 seven pounder guns).

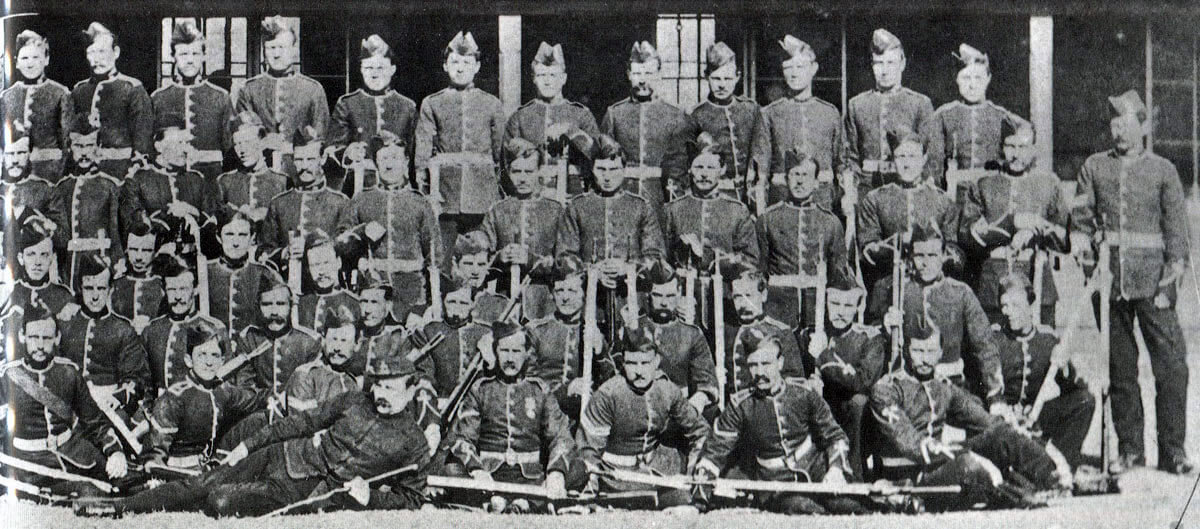

5 companies of 1st Battalion, the 24th Foot

1 company of 2nd Battalion, the 24th Foot

Mounted volunteers and Natal Police

2 companies of the Natal Native Infantry

Account of the Battle of Isandlwana:

The battle of Isandlwana stunned the world. It was unthinkable that a ‘native’ army armed substantially with stabbing weapons could defeat troops of a western power armed with modern rifles and artillery, let alone wipe it out.

Until news of the disaster reached Britain, the Zulu War was just another colonial bushfire war of the sort that simmered constantly in many parts of the worldwide British Empire. The loss of a battalion of troops, news of which was sent by telegraph to Britain, transformed the nation’s attitude to the war.

H Company, 1st/24th Regiment, annihilated at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War

The Zulu War began in early January 1879 as a simple campaign of expansion. British colonial officials and the commander-in-chief in South Africa, Lord Chelmsford, considered the independent Zulu Kingdom ruled by Cetshwayo a threat to the British colony of Natal, with which it shared a long border along the Buffalo River.

In December 1878, the British authorities delivered an ultimatum to Cetshwayo, requiring him to give up a group of Zulus accused of murdering a party of British subjects. In the absence of a satisfactory response, Chelmsford attacked Zululand on 11th January 1879.

Chelmsford’s previous wars in South Africa did not prepare him for the highly aggressive form of warfare practised by the Zulus.

Chelmsford divided his force into three columns. Colonel Evelyn Wood VC, of the 90th Light Infantry, commanded the column that crossed the Buffalo River into the North of Zululand. Colonel Pearson, of the 3rd Foot (the Buffs), commanded in the south, by the Indian Ocean coast. Colonel Glynn, of the 24th Foot, commanded the Centre Column, comprising both battalions of the 24th Foot, units of the Natal Native Infantry, Natal irregular horse and Royal Artillery.

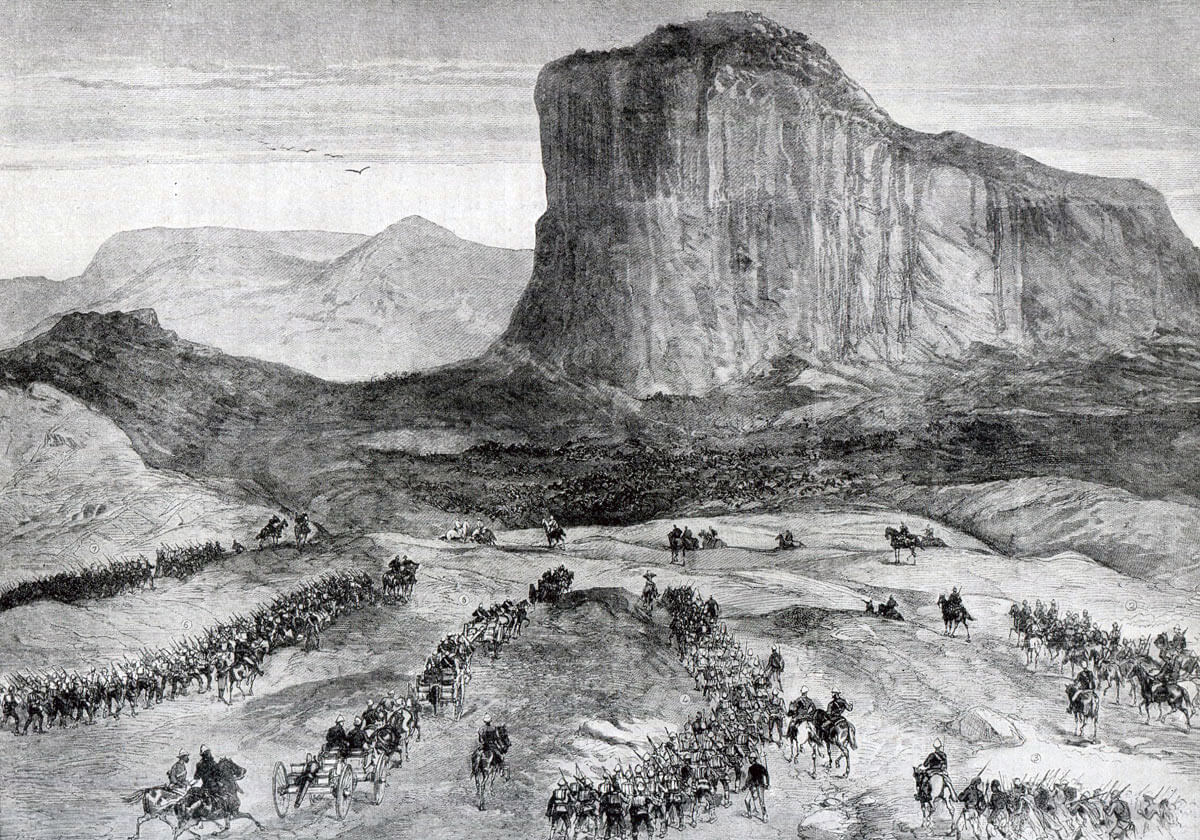

Number Three (Centre) Column on the march in Zululand: Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War: picture by Melton Pryor

Chelmsford accompanied the Centre Column into Zululand on 11th January 1879, crossing the Buffalo River at Rorke’s Drift. The column was to make for Ulundi, Cetshwayo’s principal kraal, joining Pearson’s southern column for the final assault. A Company of the 2nd Battalion, 24th Foot, remained at Rorke’s Drift, the advanced base for the column.

The Centre Column carried all its supplies in ox carts, each pulled by a team of up to twenty oxen, walking at a slow deliberate pace. A considerable part of the day was devoted to feeding and caring for the oxen. The country was hilly scrubland, without roads and progress was painfully slow. Hilltops had to be picketed and the country scouted carefully for Zulus in ambush. Movement was further hampered by heavy rain, causing the rivers and streams to swell and deepen.

Signallers of the 24th Regiment: Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War: picture by Orlando Norie

Chelmsford’s original plan had envisaged five columns crossing the Buffalo River. Shortage of troops forced him to reorganise his force into the three columns. Chelmsford required the original Number Two Column under Colonel Durnford, a Royal Engineers officer with considerable experience in commanding irregular South African troops, to act in conjunction with Glynn’s Centre Column.

Chelmsford decided to head for Isandlwana Hill. Isandlwana can be seen from Rorke’s Drift, distinctive shape some 10 miles into Zulu country, that the British troops likened to a Sphinx or a crouching lion. The shape of this strange feature adds substantially to the macabre aura that hangs over the Battle of Isandlwana.

In the face of the invasion, Cetshwayo mobilised the Zulu armies on a scale not seen before, possibly some 24,000 warriors. The Zulu force divided into two, one section heading for the Southern Column and the remainder making for Chelmsford’s Centre Column.

The Centre Column reached Isandlwana on 20th January 1879 and encamped on its lower slopes.

On 21st January 1879, Major Dartnell led a mounted reconnaissance in the direction of the advance. He encountered the Zulus in strength. Dartnell’s command was unable to disengage from the Zulus until the early hours of 22nd January 1879.

Receiving Dartnell’s intelligence, Chelmsford resolved to advance against the Zulus with a sufficient force to bring them to battle and defeat them. 2nd Battalion, 24th Foot, the Mounted Infantry and four guns were to march out, as soon as it was light.

Colonel Pulleine was left in camp with the 1st Battalion of the 24th Foot. Orders were sent to Colonel Durnford to bring his column up to reinforce the camp.

Early on the morning of 22nd January 1879, Chelmsford advanced with his force and joined Dartnell. The Zulus however had disappeared. Chelmsford’s troops began a search of the hills.

The Zulus had bypassed Chelmsford and moved on to Isandlwana. The first indication in the British camp that there was likely to be a Zulu threat came when parties of Zulus were seen on the hills to the north-east and then to the east.

Colonel Pulleine, the officer in command in the camp, ordered his troops to form to the east, the direction in which the Zulus had appeared. Pulleine dispatched a message to Chelmsford, warning him that the Zulus were threatening the camp.

Two 7 pounder RML guns captured by the Zulus at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War

At about 10am, Colonel Durnford arrived at Isandlwana with a party of mounted men and a rocket troop.

Durnford promptly left the camp to follow up the reports of the proximity of the Zulus and Pulleine agreed to support him, if he found himself in difficulties. Captain Cavaye’s company of the 1st/24th was placed in piquet on a hill to the north. The remainder of the troops in camp stood down.

On the heights, Durnford’s mounted troops spread out and searched for the Zulus. One troop of volunteers pursued a party of Zulus as they retired, until suddenly out of a fold in the ground the whole Zulu army appeared.

The Zulus were forced to act by the sudden appearance of the mounted volunteers and advanced in some confusion, shaking out as best they could into the traditional form of assault: the left horn, the central chest of the attack and the right horn.

Lord Chelmsford’s column fetching away the wagons after the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War: picture by Melton Pryor

One of Durnford’s officers rode back to Isandlwana, to warn the camp that it was about to be attacked.

Pulleine had just received a message from Chelmsford, ordering him to break camp and move up to join the rest of the column. On receipt of Durnford’s message, Pulleine deployed his men to meet the crisis.

It is thought that neither Pulleine, nor any of his officers, appreciated the scope of the threat from the Zulus or the size of the force that was advancing on them. Pulleine acted as if the only need was to support Durnford. He sent a second company under Captain Mostyn to join Captain Cavaye’s company on the hill and two guns were moved to the left of the camp, with companies of foot to support them.

As the Zulus advanced, Durnford’s rocket troop was overwhelmed and the equipment taken, the Royal Artillery crews managing to escape.

The main Zulu frontal assault now appeared over the ridge and Mostyn’s and Cavaye’s companies hastily withdrew to the camp, pausing to fire as they went.

Pulleine’s battalion, drawn up in front of the camp at the base of the ridge, opened fire on the advancing Zulus of the ‘chest’, who found themselves impeded by the many dongas, or gullies, in their path and eventually went to ground.

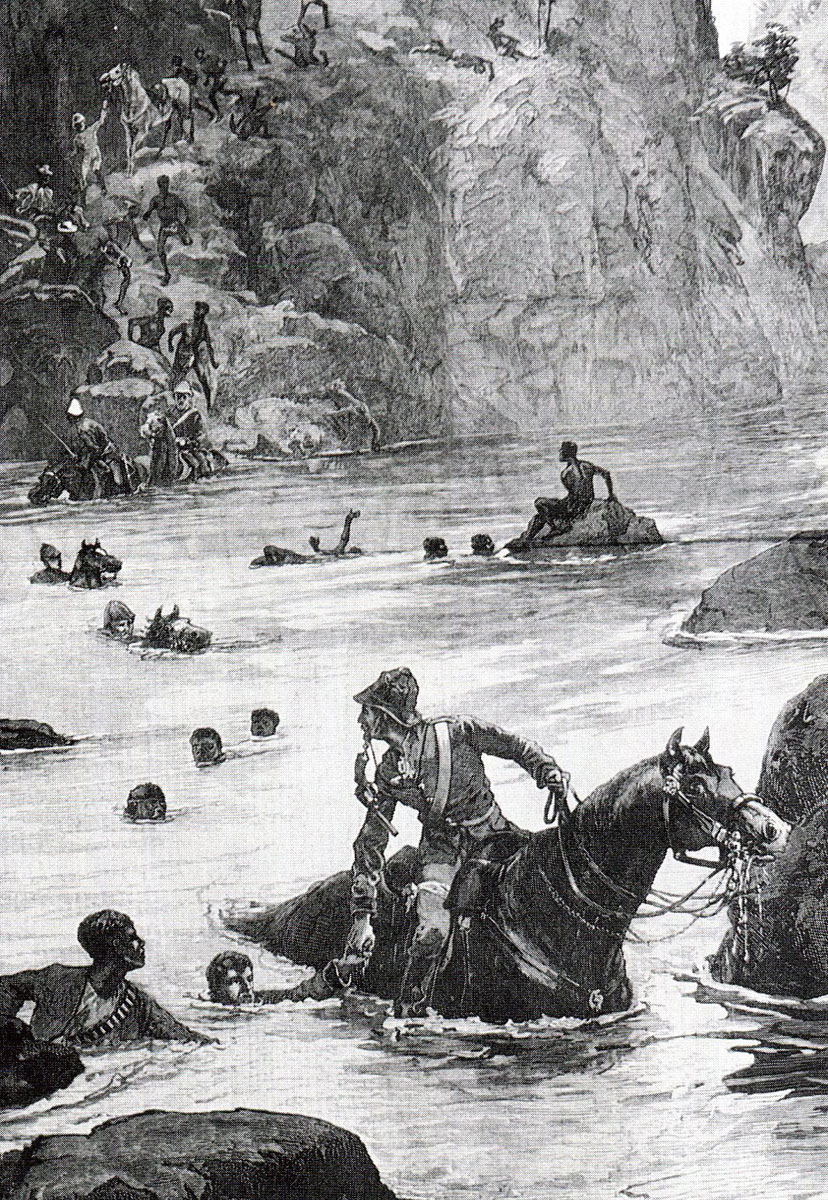

British troops escaping across the Buffalo River after the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War

The danger to the British line was presented by the Zulu ‘horns’, which raced to find the end of the British flank and envelope it.

On the British right, the companies of the 24th and the Natal Native Infantry were unable to prevent this envelopment. In addition, the Zulus were able to infiltrate between the companies of British foot and the irregulars commanded by Durnford.

It is said that a major problem for the British was lack of ammunition and failings in the system of re-supply. It seems that this was not so for the 24th. However, Durnford’s men on the extreme right flank did run out of ammunition and were forced to mount up and ride back to the camp, thereby leaving the British flank open.

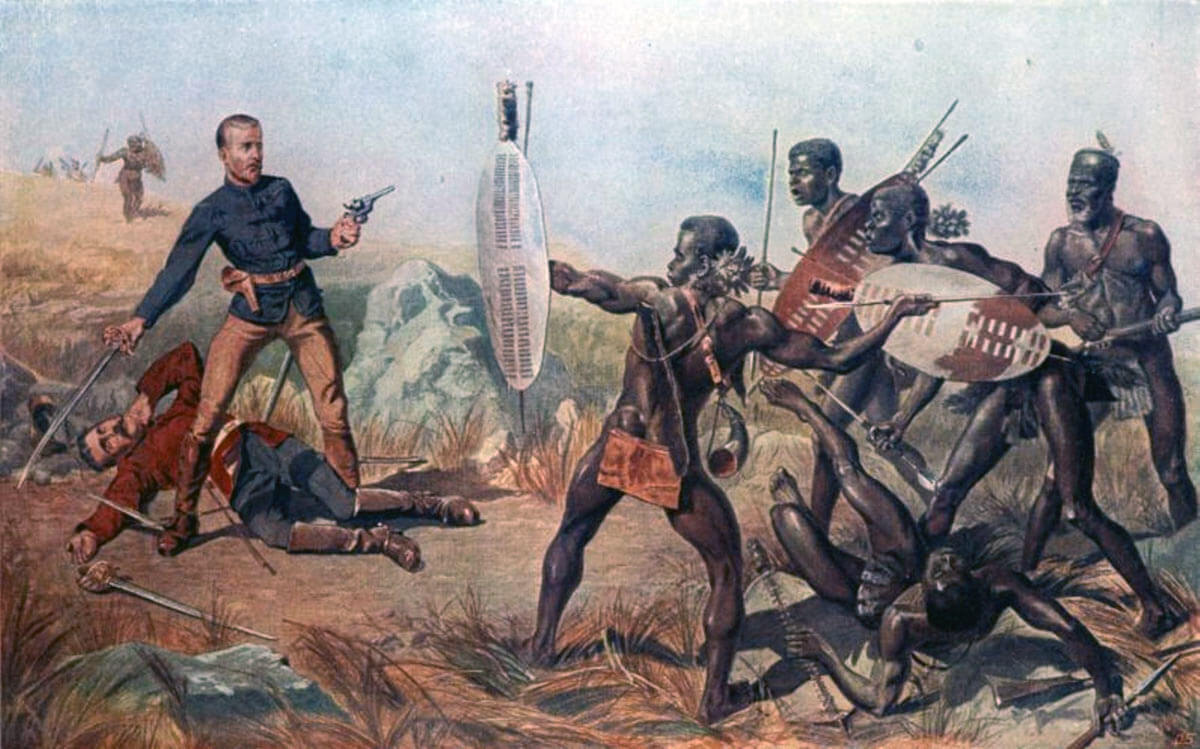

Attempted escape of Lieutenants Melville and Coghill with the Queen’s Colour of the 24th Regiment at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War

The Zulu chiefs took this opportunity to encourage the warriors of the ‘chest’, until now pinned down by the 24th’s fire, to renew their attack. This they did, causing the British troops to fall back on the encampment.

A Zulu regiment rushed between the withdrawing British centre and the camp and the ‘horns’ broke in on each flank. The British line quickly collapsed.

Lieutenants Melville and Coghill rescue the colour of the 24th Regiment at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War: picture by Alphonse de Neuville

As the line broke up, groups formed and fought the Zulus, until their ammunition gave out and they were overwhelmed. A section of Natal Carbineers, commanded by Durnford, is identified as giving a heavy fire, until their ammunition was spent. They fought on with pistols and knives, until they were all struck down.

The ‘horns’ of the Zulu attack did not quite close around the British camp, some soldiers managing to make their way towards Rorke’s Drift. But the Zulus cut the road and the escaping soldiers from the 24th were forced into the hills, where they were hunted down and killed. Only mounted men managed to make it to the river by the more direct route to the south-west.

A group of some sixty soldiers of the 24th Foot under Lieutenant Anstey were cornered on the banks of a tributary of the Buffalo and wiped out.

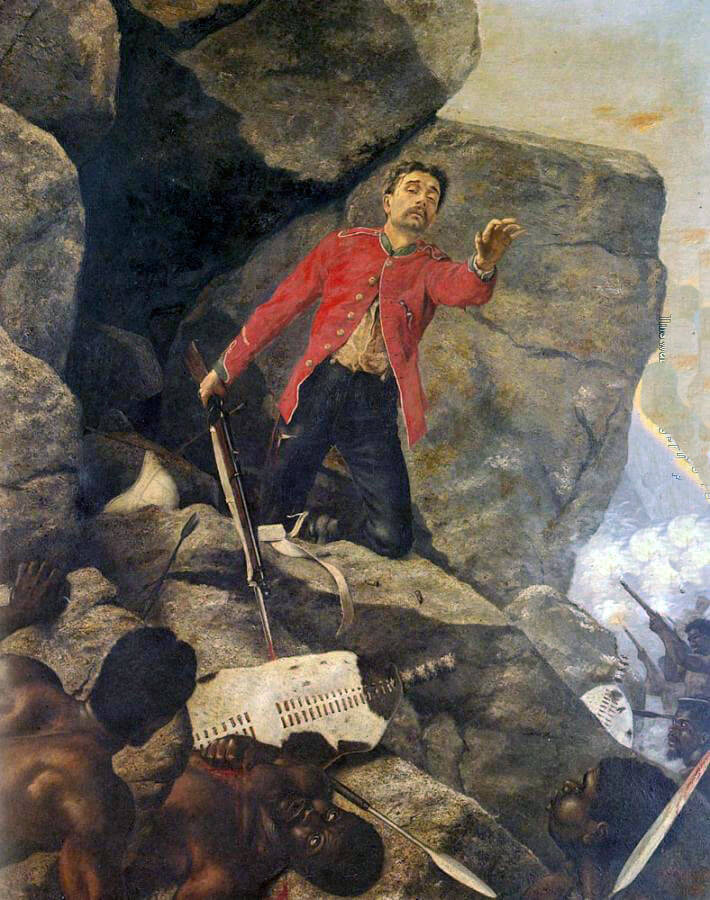

‘The Last of the 24th’ at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War: picture by Richard Thomas Moynan

The last survivor of the main battle, a soldier of the 24th, escaped to a cave on the hillside where he continued fighting until his ammunition gave out and he was shot down.

The final act of the drama was played out along the banks of the Buffalo River. Numbers of men were caught there by the Zulus. It is thought that natives living in Natal came down to the river and, on the urgings of the Zulus, killed British soldiers attempting to escape.

Deaths of Lieutenants Melville and Coghill at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War

The most memorable episode of this stage of the battle concerns Lieutenants Melville and Coghill. Melville was the adjutant of the 1st Battalion, the 24th Foot. He is thought to have collected the Queen’s Colour from the guard tent towards the end of the battle and ridden out of camp, heading for the Buffalo River. Melville arrived at the river, in flood from the rains and plunged in. Half-way across, Melville came off his horse, still clutching the cased colour. Coghill, also of the 24th Foot, crossed the river soon after and went to Melville’s assistance. The Zulus were, by this time, lining the bank and opened a heavy fire on the two officers. Coghill’s horse was killed and the colour swept away. Both officers struggled to the Natal bank, where it seems likely that they were killed by Natal natives.

Melville and Coghill probably died at around 3.30pm. At 2.29pm there was a total eclipse of the sun, briefly plunging the terrible battle into an eerie darkness.

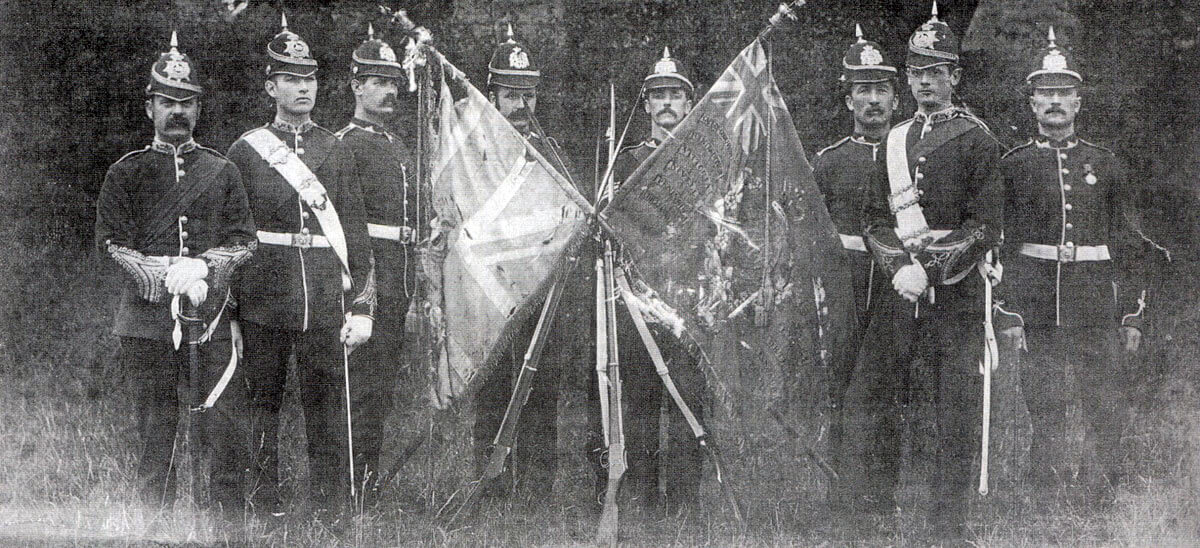

Colours of 1st/24th Regiment presented to Queen Victoria on 28th July 1880: Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War: the Queen’s Colour on the left was recovered from the scene of the battle

Casualties at the Battle of Isandlwana:

52 British officers and 806 non-commissioned ranks were killed. Around 60 Europeans survived the battle. 471 Africans died fighting for the British. Zulu casualties have to be estimated and are set at around 2,000 dead, either on the field or from wounds. The Zulus captured 1,000 rifles with the whole of the column’s reserve ammunition supply.

Follow-up to the Battle of Isandlwana:

Chelmsford’s force was unaware of the disaster that had overwhelmed Pulleine’s troops, until the news filtered through that the camp had been taken. Chelmsford was staggered. He said, ‘But I left 1,000 men to guard the camp.’

Chelmsford’s column returned to the scene of horror at Isandlwana and camped near the battlefield.

Chelmsford’s nightmare was that the Zulus would invade Natal. In the distance, the British could see Rorke’s Drift mission station burning. From that, Chelmsford knew that the Zulus had crossed the Buffalo River.

Arrival of Lord Chelmsford after the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War: picture by Melton Pryor

In the longer term, the British Government determined to avenge the defeat and overwhelming reinforcements were dispatched to Natal. General Sir Garnet Wolseley was sent to replace Lord Chelmsford, arriving after the final battle of the war. Cetshwayo’s overwhelming success at Isandlwana secured his ultimate downfall.

Private Samuel Wassall of the 80th Regiment awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions at the Battle of Isandlwana on 22nd January 1879 in the Zulu War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Isandlwana:

- Private Samuel Wassall was awarded the Victoria Cross for his conduct at the battle. Attached to the Mounted Infantry, Wassall escaped on his horse from the battle and crossed the Buffalo River. He then saw a comrade from the Mounted Infantry struggling in the water. Wassall recrossed the river, tethered his horse, swam over to the soldier and dragged him ashore on the Zulu side. The two men plunged back into the Buffalo River and swam to safety on Wassall’s horse, as the Zulus came up.

- The Queen’s colour of the 1st Battalion, 24th Foot, was recovered from the Buffalo River. The colour was presented to Queen Victoria, who placed a wreath of silver immortelles on the tip of the staff. Lieutenants Melville and Coghill were awarded posthumous Victoria Crosses.

References for the Battle of Isandlwana:

Rorke’s Drift and Isandlwana by Ian F.W. Beckett: Oxford University Press (a particularly interesting history of the two battles with a consideration of their place in British and Zulu culture)

Washing of the Spears by D. Morris

Zulu War by Ian Knight

Recent British Battles by Grant

52. Podcast on the Battle of Isandlwana fought on 22nd January 1879; where the Zulus wiped out a substantial British force rocking British Victorian society: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

52. Podcast on the Battle of Isandlwana fought on 22nd January 1879; where the Zulus wiped out a substantial British force rocking British Victorian society: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Kandahar

The next battle of the Zulu War is the Battle of Rorke’s Drift