King Edward IV’s victory over his erstwhile ally, the Earl of Warwick, on 14th April 1471

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Towton

The next battle in the Wars of the Roses is the Battle of Tewkesbury

Battle: Barnet

War: Wars of the Roses

Date of the Battle of Barnet: 14th April 1471

Place of the Battle of Barnet: At Barnet in Hertfordshire, to the north of London

Combatants at the Battle of Barnet: Lancastrians against the Yorkists

King Edward IV, Yorkist commander at the Battle of Barnet on 14th April 1471 in the Wars of the Roses

Commanders at the Battle of Barnet:

The Earl of Warwick, with the Duke of Somerset, the Earl of Oxford and the Duke of Exeter, commanded the Lancastrian army.

King Edward IV, with his brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester (later King Richard III) and Lord Hastings, commanded the Yorkist army.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Barnet: The Lancastrian army probably comprised some 10,000 men, the Yorkist army some 8,000 men.

Winner of the Battle of Barnet: The Yorkists, decisively.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Barnet: The male commanders and their noble supporters and knights rode to battle on horseback, in armour, with sword, lance and shield.

Their immediate entourage comprised mounted men-at-arms, in armour and armed with sword, lance and shield, although often fighting on foot.

Both armies relied upon strong forces of longbowmen.

Handheld Firearms were beginning to appear on the battlefield but were still unreliable and dangerous to discharge.

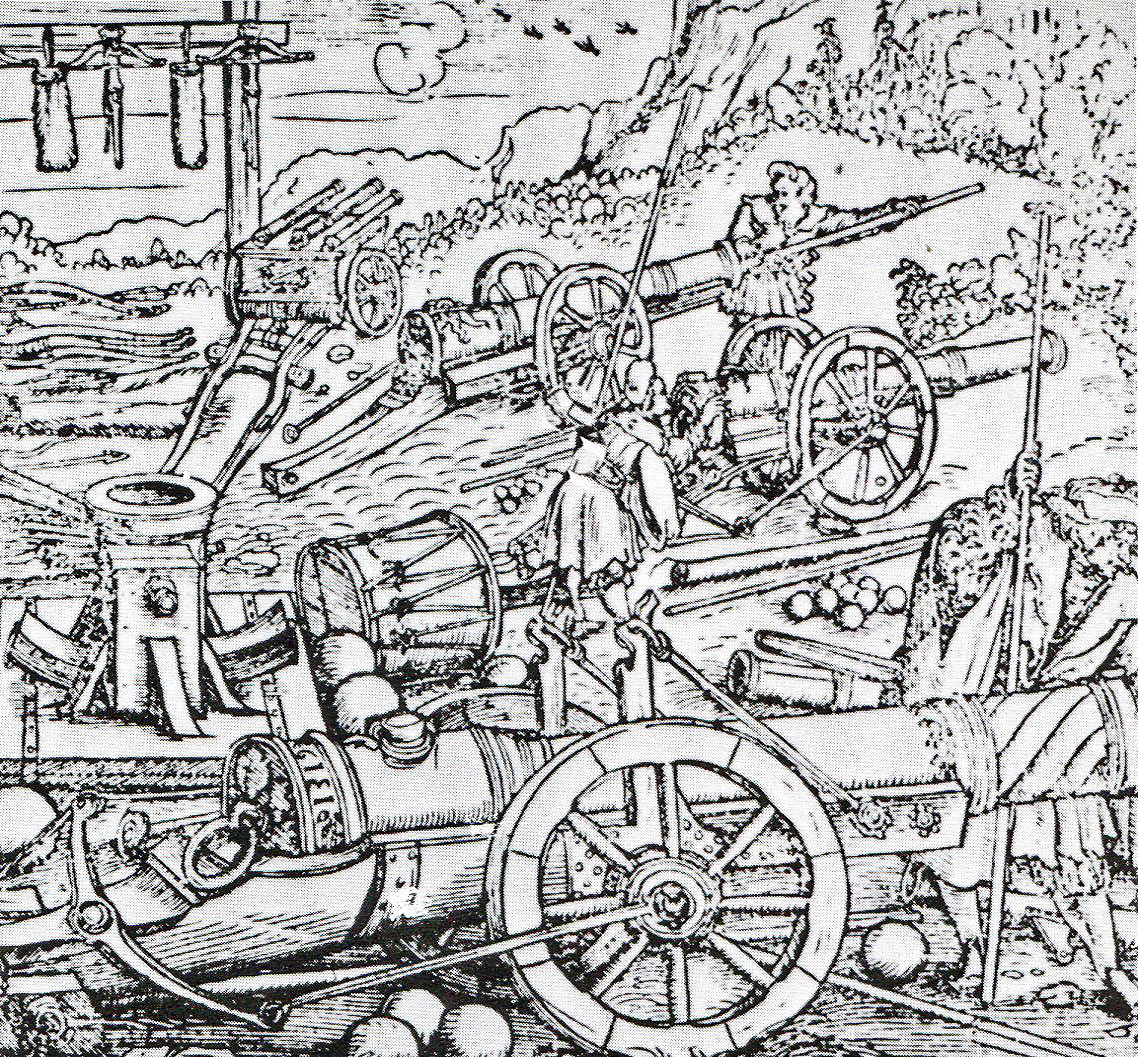

Artillery, although widely used in warfare, was heavy, cumbersome and difficult to move and fire.

Earl of Warwick, ‘Warwick the Kingmaker’, Lancastrian commander killed at the Battle of Barnet on 14th April 1471 in the Wars of the Roses

The Lancastrian army comprised a strong artillery arm, that carried out a bombardment of the Yorkist camp during the night prior to the Battle of Barnet. The bombardment was largely ineffective due to the fog and the position of the Yorkist army, much closer than was calculated.

The central core of the army that landed with King Edward IV in April 1471 was a force of Burgundian mercenary hand-gunners.

The end of the Hundred Years War caused numbers of English and Welsh men-at-arms and archers to return to their home countries from France. The wealthier English and Welsh nobles were able to recruit companies of disciplined armed retainers from these veterans, forming the backbone of their field armies.

Background to the Battle of Barnet: Following the Battle of Towton, Edward, Duke of York, was crowned King Edward IV of England on 26th June 1461.

The Lancastrian King Henry VI, effectively deposed by Edward, escaped to Scotland with Queen Margaret of Anjou and the Prince of Wales after the Battle of Towton.

In 1464, King Henry VI was taken in Lancashire and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Otherwise, things did not go well for King Edward IV. His secret love marriage to Elizabeth Woodville enraged the Earl of Warwick, whose maneouvrings for King Edward to marry a French princess were rendered ridiculous by the King’s actions. The sudden elevation of the Woodville family, by Elizabeth’s marriage to the King, upset many members of the aristocracy, previously supporters of Edward.

Warwick inspired an unsuccessful revolt against King Edward by his younger brother, the Duke of Clarence (reputed to have been later drowned in a butt of Malmsey Wine at Edward’s direction).

Warwick and his supporters were forced to flee to France, where they entered into an uneasy alliance with Queen Margaret.

On 13th September 1470, Warwick landed at Plymouth, intending to replace Edward IV with Henry VI and was joined by many Lancastrian nobles and supporters.

Taken by surprise, King Edward IV was forced to fly the country for Burgundy. King Henry VI was brought from the Tower to resume his troubled reign.

In April 1471, King Edward IV landed at Ravenspur in Yorkshire and occupied York, after the city opened its gates to his army.

From York, King Edward IV marched south to Nottingham, where he declared himself again King of England and was joined by Sir Thomas Parre, Sir James Harrington, Sir William Stanley and Sir William Norris with their personal entourages.

The Earl of Warwick took refuge in the walled city of Coventry and waited to be joined by his brother, Lord Montagu.

The Duke of Clarence changed sides, joining King Edward at Banbury with his troops.

Edward marched to London, where the Yorkist sympathisers opened the gates and joined his Queen, until then in sanctuary in Westminster Abbey with her sons.

Warwick, hurrying south in an attempt to catch Edward’s army before he entered London, learnt of the loss of the capital at Dunstable on Good Friday, 12th April 1471.

Warwick reached St Albans that day and the next day he marched on to within a half mile of Barnet, a Hertfordshire town on the final stretch of the road to London.

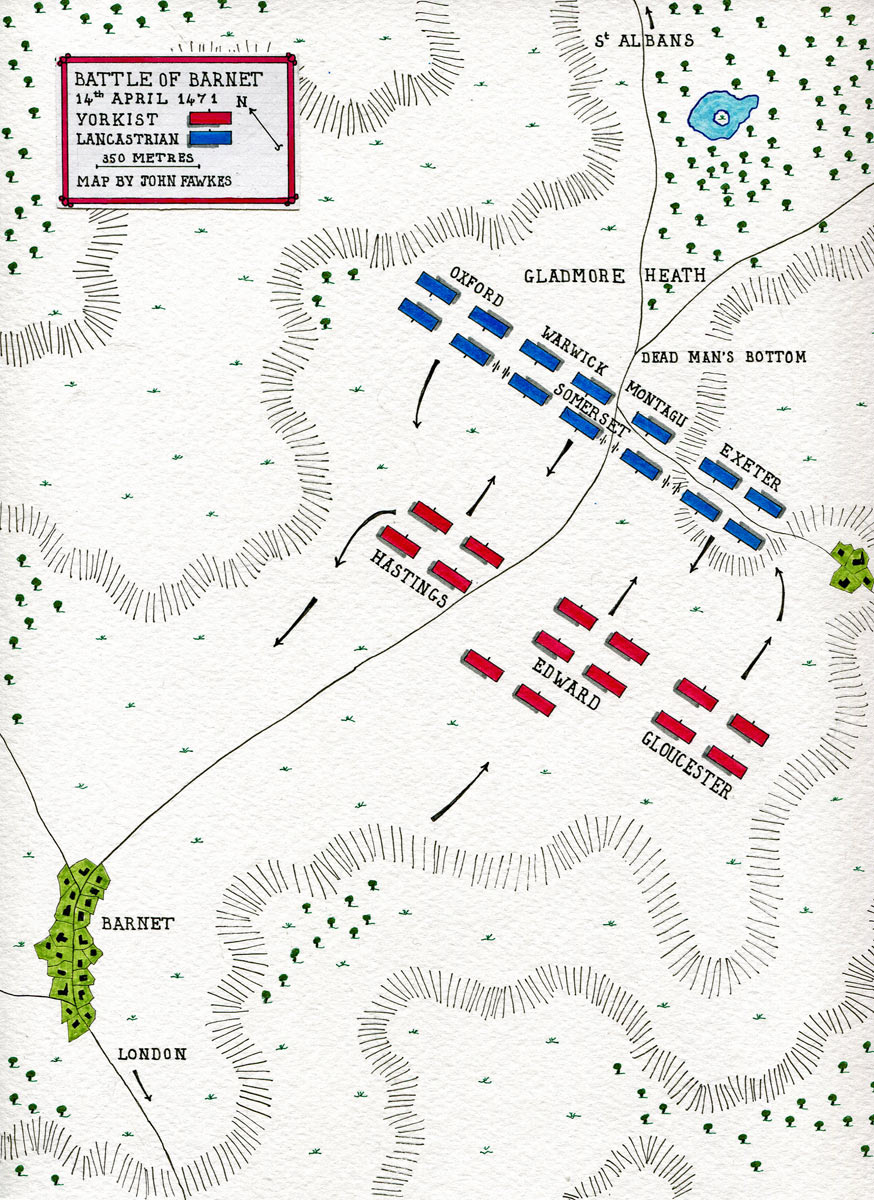

Hearing that Edward was advancing from London to meet him, Warwick deployed his army on Gladmore Heath (now called Hadley Green), to the north of Barnet.

———————————-

Account of the Battle of Barnet:

King Edward IV left London with his army on Easter Saturday 13th April 1471 and arrived in Barnet that evening.

The again-deposed King Henry VI was brought along with the Yorkist army.

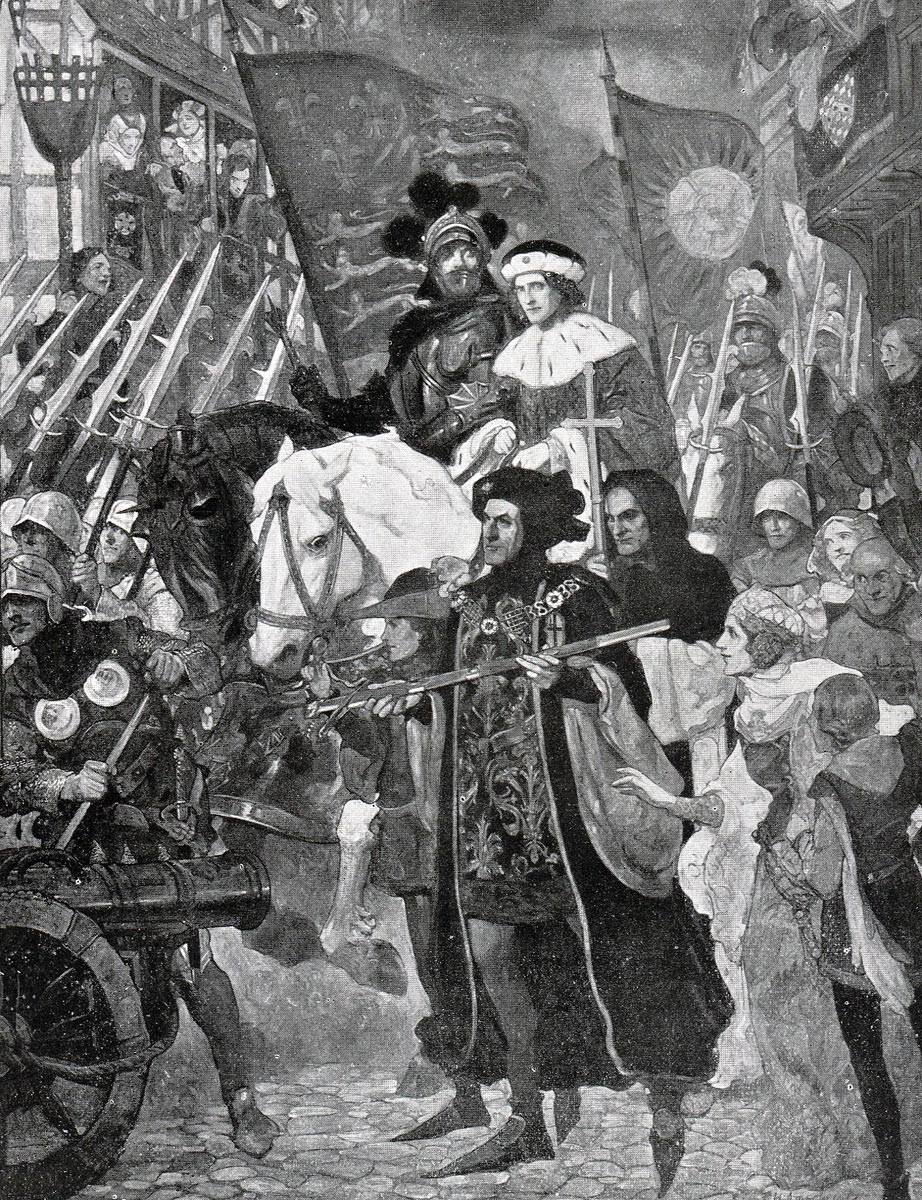

Army of Edward IV heading for Barnet with Henry VI as prisoner: Battle of Barnet on 14th April 1471 in the Wars of the Roses

Aware that Edward’s army was approaching from London, Warwick halted his army on the ridge that lies on the London Road, a half-mile to the north of Barnet.

The Lancastrian army formed for battle, with the Earl of Oxford commanding the right-hand division, the centre commanded by the Duke of Somerset and the left by the Duke of Exeter.

Warwick was probably in the centre behind Somerset’s division.

Mounted men were positioned on each flank and the archers concentrated in Somerset’s central division.

The Lancastrian army camped for the night in this formation.

King Edward’s army arrived in Barnet as night was falling. The army marched through Barnet to encamp near the Lancastrian lines, in order of battle, ready for an attack at first light.

The Yorkist right was commanded by Richard, Duke of Gloucester (later King Richard III), the centre by King Edward and the Yorkist left by Lord Hastings.

King Edward kept his unreliable brother, the Duke of Clarence, with him in the central division.

Somewhere in the Yorkist centre was the unhappy King Henry.

The final Yorkist approach march was made in darkness and the Yorkists miscalculated the Lancastrian position, with the result that the Yorkist line overlapped the Lancastrian position, but only with the left and centre divisions.

The Yorkist right did not face any enemy and Lord Hastings’ left division was outflanked by the right-hand Lancastrian division.

In addition, the Yorkists encamped closer to the Lancastrian line than was intended, again due to the dark.

The Yorkist mispositioning was fortunate in one respect, as throughout the night the Lancastrian guns kept up a blind firing, in the expectation that their cannon balls would land on the Yorkist camp.

The balls either passed over the Yorkist heads or fell in open ground to their left.

The area in which the two opposing armies were encamped was boggy. As dawn broke a fog built up over the saturated ground, restricting vision to a few yards.

The soldiers were only aware of the proximity of the enemy by the sounds of trumpets and drums and the movements of heavily armoured men.

At around 5am the order was given to attack and the two armies advanced on each other.

This was a battle fought on foot with few in either army mounted. Warwick sent his horse to the rear and marched with his men. It is reported that King Edward fought the battle on his white steed.

The two armies loomed up on each other and began a terrible hand-to-hand struggle.

As the armies clashed, the Yorkist right wing, led by Gloucester, found there were no Lancastrian troops opposite them.

Gloucester’s wing swung round and assaulted the flank of Exeter’s Lancastrian left division.

The going was slow and difficult as Gloucester’s men were forced to attack the Lancastrians up an incline.

On the other flank the Earl of Oxford’s Lancastrian troops were experiencing the same lack of an enemy. They also swung round and attacked the Yorkist wing, but with much greater effect, having no incline to negotiate.

Taken in the flank, Lord Hasting’s Yorkist division dissolved in flight, pursued by the Earl of Oxford’s Lancastrians into Barnet, where they pillaged the town.

Meanwhile the centre formations of each army fought it out in the fog.

The effect of the attack on its left flank caused the Lancastrian army to swing round and face east, while the Yorkists found themselves facing west.

Rallying some of his men, Lord Oxford returned from Barnet, but instead of making contact with the rear of the Yorkist centre, Oxford encountered the Lancastrians of Somerset’s centre division.

Somerset’s troops mistook Oxford’s men for Yorkists and subjected them to a hail of arrows, before charging them. Fearing that this was no mistake the troops took up the cry of ‘Treason’.

Treasonous changing of sides, often in mid-battle, was a frequent event in the Wars of the Roses, inevitably leading to a loss of morale for the side effected. The word spread through the Lancastrian ranks with catastrophic consequences.

Believing that Warwick’s army had been betrayed, the Earl of Oxford left the field with such of his men as he could rally. The troops in Somerset’s central division began to follow.

The battle was now around three hours old and both sides were near exhaustion.

This was the point at which King Edward’s qualities of leadership proved decisive. He committed his reserve and urged his troops to renew the attack.

As the day progressed the fog lifted, revealing the Lancastrian soldiery streaming away to the north.

Of the Lancastrian leadership, Lord Montagu had been killed. Exeter was said to be dead but was in fact wounded and survived the battle. Somerset was following Lord Oxford off the field.

Death of the Earl of Warwick, ‘Warwick the Kingmaker’ at the Battle of Barnet on 14th April 1471 in the Wars of the Roses

The Earl of Warwick attempted to leave the battlefield but was killed trying to reach his horse.

The Lancastrians were pursued across an area of ground subsequently called ‘Dead Man’s Bottom’.

The Yorkist army of King Edward IV had triumphed decisively.

Casualties at the Battle of Barnet:

It seems likely that around 2,000 Lancastrians were killed in the battle and subsequent pursuit.

Probably around 500 Yorkists were killed.

The dead soldiery was buried in a common grave and a chapel erected on the site.

Of the senior Yorkists, Lord Saye and Sele, Sir John Lisle, Sir Thomas Parre, Lord Cromwell, Viscount Bourchier and Sir Humphrey Bourchier were killed.

The most significant death at the Battle of Barnet was that of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, known as ‘Warwick the Kingmaker’.

Follow-up to the Battle of Barnet: On the day of the Battle of Barnet, Queen Margaret of Anjou landed at Weymouth to join the Earl of Warwick in his attempt to repel the return of King Edward IV.

News of the disaster at the Battle of Barnet and the death of her ally, the Earl of Warwick, nearly caused Margaret to return to France.

Queen Margaret was persuaded to continue in her attempt to re-instate her husband, King Henry VI, on the throne of England, in the interests of her son, the Prince of Wales.

Her attempt led to the Battle of Tewkesbury.

Emblems of the Battle of Barnet: The Earl Oxford’s standard showed a ‘Radiant Star’.

King Edward IV’s banner was worked with a ‘Sun with Rays’.

When Oxford’s Lancastrians returned from Barnet and attempted to rejoin the battle, Somerset’s men are said to have been confused by the similarity of the devices and feared they were about to be attacked by the Yorkists, leading them to loose a heavy discharge of arrows on Lord Oxford’s returning Lancastrians and attack them.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Barnet:

- It is said that King Edward IV maintained a reserve of men behind the three main divisions and that the committal to battle of this reserve in the closing phase of the battle proved decisive in finally breaking the Lancastrians.

- King Edward IV kept his Lancastrian prisoner, King Henry VI, in his line during the battle. After the Battle of Barnet, King Henry was returned to his cell in the Tower of London.

- It is reported that many of the soldiers in the defeated Yorkist left wing fled to London and reported the defeat of King Edward IV.

- Enraged that so many of the soldiers that had fought for the Yorkists were joining Warwick’s army, King Edward IV abandoned his usual practice of quarter for captured ordinary soldiers and ordered that no quarter be given to the opposing soldiery.

- The Earl of Oxford, after the Battle of Barnet, journeyed to Cornwall with some of his soldiers. He obtained entry to St Michael’s Mount on the pretence that his party were pilgrims and massacred the Yorkist garrison.

- The Duke of Exeter, although severely wounded in the Battle of Barnet, managed to reach London, where he sought sanctuary in Westminster Abbey.

- The bodies of the Earl of Warwick and his brother, John Neville, Marquis of Montague, were displayed for three days in St Paul’s Cathedral in London, before being taken to Bisham Abbey in Berkshire, the hereditary burial place of the Neville family and there buried.

- An obelisk in memory of the Battle of Barnet was erected on the site of the battle in 1740 by Jeremy Sambroke.

References for the Battle of Barnet:

Battles in Britain by William Seymour

Wars of the Roses by Michael Hicks

Chronicles of the Wars of the Roses

British Battles by Grant

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Towton

The next battle in the Wars of the Roses is the Battle of Tewkesbury