Vespasian and the Roman Conquest of Britain in 43 AD

Roman fleet landing on the coast of Britain for the Emperor Claudius’ invasion of Britain. Picture by Harry Payne

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Ashdown

To the Wars of Roman Britain Index

Battle of Medway

War : Roman Invasion of Britain

Date : Early June 43 AD

Place : 4 miles south west of Rochester, Kent, England

Battle : The Battle of Medway

Generals – British – Togodumnus and Caratacus.

Generals – Roman – Plautius, Galba, Sabinus, Geta, & Vespasian who commanded II Legion

Size of the Armies : British 150,000 – Roman 45,000

Guest Author : The author of this essay is David Young ([email protected]). David was in the British Army for 26 years. During that period he studied at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and the Royal School of Military Engineering. He passed many military examinations including the important Staff College Entrance Examination. This military expertise gives this document extra value. Nevertheless it must be emphasised that many aspects of Part Three have doubtful historical merit, as the only known relevant fact is that Vespasian and his legion had a base near Chichester.

David Young also contributed the Battle of Ashdown to the britishbattles.com site.

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this essay is to stimulate the general reader to consider further the events described, maybe by reading one of the books listed at the end or visiting a place mentioned.

The essay thus makes no attempt to be an academic document, although the author is very willing to attempt to justify any of his statements. Consequently there are no footnotes [although helpful additional comments and inessential information are provided in square brackets]. (Round brackets, however, are used as normal punctuation.) To assist the reader, current English place names have normally been used.

This essay considers the role of II Legion from AD 43 to 45 and its part in the Roman invasion of Britain. Its strategic objective was to subdue Southern England. Its legate was Titus Flavius Vespasian [born 17/11/0009; died 23/6/0079]. He was the Roman Emperor from AD 69 to 79. Historians describe him as positive, successful and well-respected.

The invasion marks the boundary between British pre-history and history. With the Romans in control of what we now call England and Wales, civilisation had arrived. Many benefits survive to the current era. This was in great contrast to the position before AD 43. The Battle of the Medway can reasonably be described as one of the two most important battles in British history. The author of this essay is happy to conduct tours of the battlefield.

This essay is in four parts: Part One outlines the situation before the Roman invasion; Part Two considers the invasion excluding Vespasian’s campaigns; Part Three speculates on Vespasian’s campaign in AD 43; Part Four imagines his campaigns in AD 44 and 45.

As part of his research, David Young has consulted many texts and walked for nearly 600 miles across southern England with his wife, Pauline, including the whole journey from Richborough to Exeter. Of the many museums visited, he found the most memorable to be, starting in the east: English Heritage at Richborough, Canterbury Roman Museum, the Museum of London, Reading Museum, Bignor Roman Villa, Fishbourne Roman Palace and lastly, the Dorchester Museum. The Reading University excavation at Silchester and Butser Ancient Farm are well worth seeing as are the Chichester and Exeter Museums.

This essay necessarily contains duplication. This is to help the reader using the internet.

The author is grateful to family and friends who have commented on his work. He hopes they will not be offended that some of their comments have been ignored. He particularly thanks britishbattles.com and the archaeologist, Andrew Hutt.

Of the many books the author studied, three must be given special mention. They are “The Roman Invasion of Britain” by Graham Webster, “Conquest The Roman Invasion of Britain” by John Peddie and “The Roman Invasions of Britain” by Gerald Grainge. Some of the views expressed by these eminent historians, and others, can however lead to very different conclusions. A general point must be made. The author found a huge number of positive historical statements made in the many worthy documents he researched. Some of these stated “facts” are however totally incorrect!

PART ONE – BEFORE THE INVASION OF AD 43

British Tribes

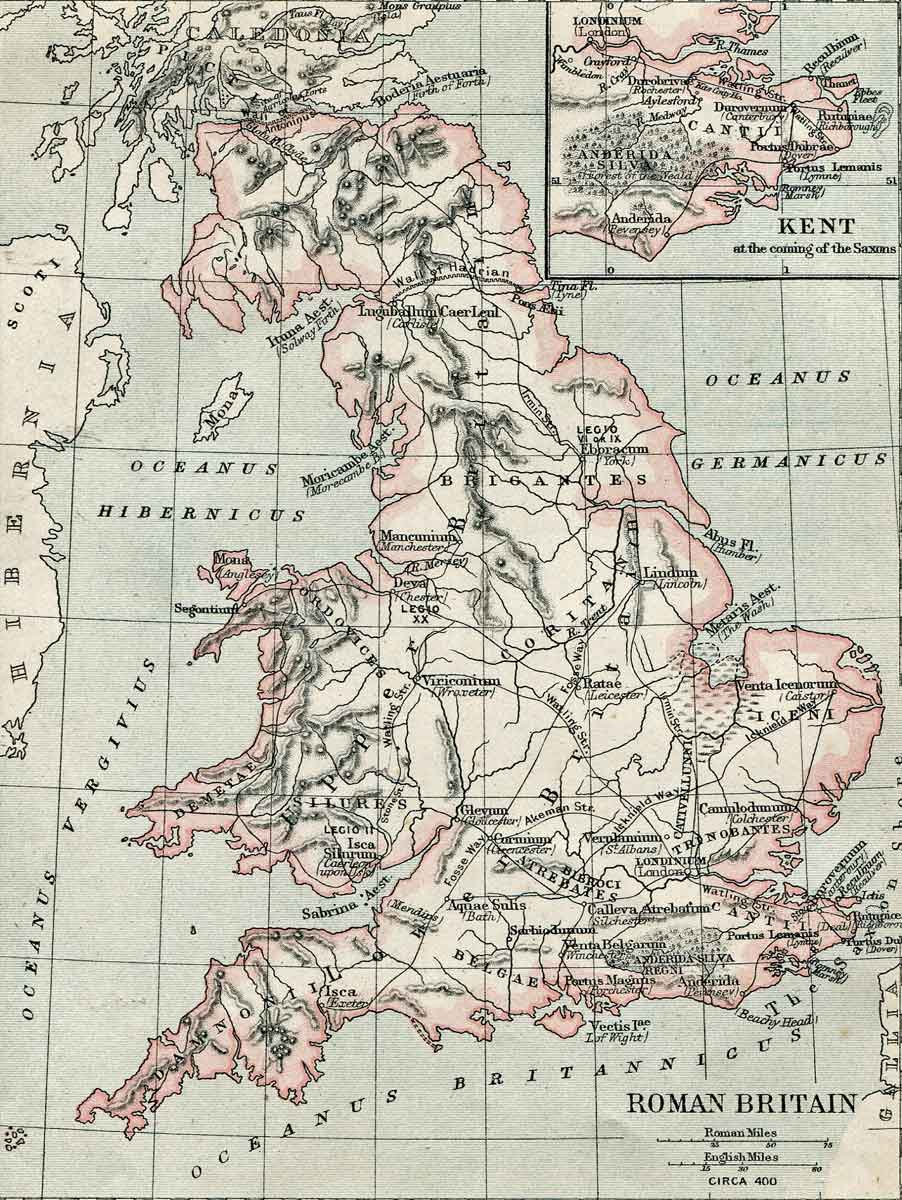

England was home to a number of British tribes that had different relationships with each other, and with the Roman Empire that dominated much of the rest of Europe. There is some disagreement amongst historians about their exact geographical locations but judgements on these are not important to this essay. Ten tribes are pertinent.

The Iceni lived in Norfolk and north Suffolk. They had little trade with Rome and were mainly ignored by the Romans [until the rising by Queen Boudicca in AD 60].

The Trinovantes lived in the areas we know as south Suffolk and Essex. Their centre was Colchester. When Julius Caesar briefly invaded in 54 BC, this tribe was one of the strongest in southern Britain. They came to an agreement with Julius Caesar and other British tribes. This that said the Trinovantes and their territory would remain unmolested.

The Catuvellauni lived north of the Thames. Originally they inhabited the areas we know as Warwickshire, Northamptonshire, Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire. Their capital was St Albans. After their defeat by Julius Caesar in 54 BC, they agreed not to attack the Trinovantes, the tribe to the east that was friendly to Rome. [The Roman Army then left Britain.] However around AD 6 the Catuvellauni broke the treaty and absorbed the area of Essex where the Trinovantes lived. They probably took over parts of south Suffolk too. The tribal capital then moved to Colchester. The Catuvellauni thus became the most powerful tribe in southern Britain. For nearly 40 years, until his death around AD 41, their king was Cunobeline. [He was named Cymbeline by Shakespeare.] His heirs were his sons, Togodumnus and Caratacus. On their death of their father, Togodumnus inherited his father’s kingdom (thus indicating that he was the elder son) whilst his brother Caratacus immediately set out to conquer other tribes of southern England. In AD 43 the brothers led the combined British force against the invading Roman Army. Their peoples thus provided the main resistance to the Roman invasion.

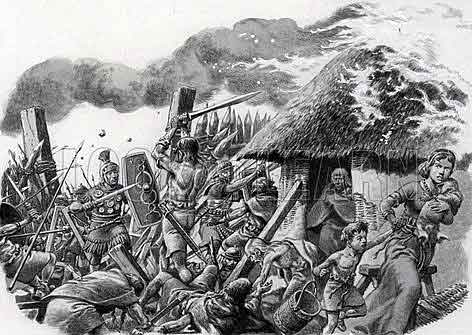

Capture of Caratacus by the Romans: Battle of Medway on 1st June 43 AD in the Roman Invasion of Britain

The Atrebates lived south of the Thames in the areas we know as south Berkshire, northeast Hampshire, Surrey and west Kent. Their capital was Calleva Atrebatum, renamed by the Romans as Silchester. They were friendly to Rome with whom they had good trading links. Verica ruled them from about AD 15 until 42. Around AD 25 a group of Catuvellauni under Epaticcus invaded the northern part of their territory including Silchester. Verica and his tribe therefore moved southwards. It is outside the scope of this essay to pronounce on whether the incursion in AD 25 by Epaticcus was permanent. The important facts are that in AD 42 Verica, a Roman ally who had recently been expelled from all his territory by Caratacus, from the Catuvellauni tribe, went to Rome to seek support from the Emperor Claudius (as described below). The historical source is Dio Cassius, probably writing in the late second century.

The Regini were also known as the Regni or Regnenses. They lived in the area we know as Sussex and east Hampshire. Their centre was Chichester. This was conveniently close to Bosham, their main harbour. Like the Atrebates, the tribe was friendly to Rome, with whom it had good trading links. A few historians deny the existence of the Regini, as they believe that the lands of the Atrebates stretched this far south. I accept the majority opinion as it seems unlikely that Silchester, being significantly further north, was then the location for control of such a large territory.

The Cantiaci were sometimes called the Cantii or Cantici. They lived in the area we now know as east Kent. Their centre was Canterbury. Like the Atrebates and the Regini, these people were also friendly to Rome, with whom they had good trading links.

The Isle of Wight may well have consisted of merely a few settlements based on fishing. They probably owed allegiance to the Regini, or possibly the Belgae.

The Belgae lived in the area we know as mid Hampshire, mid Wiltshire, north Somerset and south Gloucestershire. No coins from this tribe have been found. Thus some historians deduce that the tribe did not exist as an entity in AD 43 and that the Romans later created the Belgae tribe from groups of local people. Other experts say the tribespeople were immigrants from northern France who arrived around 100 BC. There was certainly pre-Roman habitation at Winchester, then called Oram’s Arbour. The Winchester people or Belgae tribe were unfriendly to Rome in AD 43. A more accurate name might be Southern Atrebates but I shall use the more common Belgae. Perhaps after Caratacus had evicted Verica, some of the Catuvellauni had then moved south to dominate Winchester.

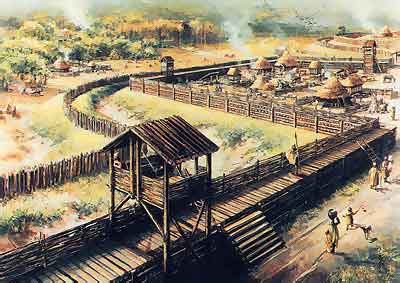

The Durotriges probably lived in the area we know as the New Forest, south Wiltshire, Dorset, south Somerset and east Devon. A possibility is that the Roman invasion of AD 43 caused the many groups of local people in these areas to unite as a single tribe. We just don’t know. In times of peace, Dorchester was the centre of these British natives. By the time of the invasion, the tribe had become very unfriendly to Rome. There are many hill forts in their area, possibly the most spectacular being at Maiden Castle. [When needed, defensive hill forts would have contained several hundred people at least, although from the Middle Iron Age, 400 to 100 BC onwards, most of the local population now moved into towns or villages near water. People lived in circular huts, up to 35 feet across. These were made of timber and thatch. It is interesting to visit Butser Ancient Farm, near Petersfield.] Most of Vespasian’s battles were with the Durotriges people.

The Dumnonii kept away from the influence of Rome. The tribe lived in west Devon and Cornwall. Probably its eastern boundary was the Rivers Exe and Lyn. There are no large hill forts in their area and no evidence of any battles. Most historians think neither Caratacus nor Vespasian invaded their lands. Vespasian would have had no need to use any of his force to take on the additional task of controlling this tribe that posed no threat to II Legion.

The Dobunni lived in an area from the lower Severn valley in the west to the Goring gap of the Thames in the east. These are areas we now know as Worcestershire, north Gloucestershire, north Wiltshire and north Berkshire. The tribe was not friendly to Rome. No evidence has been found that this tribe was within the remit of Vespasian to subdue.

AD 41 to 43

[Julius Caesar invaded Britain in 54 BC, supporting the Trinovantes against the threats of the Catuvellauni. He reached south Hertfordshire and then made a peace treaty with some British tribes. The Romans left Britain after only 2 months. It was only a short raid. Around the year AD 40 Emperor Caligula, also known as Gaius Caligula, failed in an invasion attempt. His troops were accustomed to the mostly calm Mediterranean Sea and, because of their fear of rough seas, the Army mutinied and refused to cross the English Channel.]

Caligula was murdered in AD 41. His uncle Claudius took his place as Emperor. Claudius needed to establish his prestige in Rome by some major military achievement for which he would be awarded a full “triumph”. [Such a success would result in the award by the Senate of additional titles and honours, the minting of special coins, the holding of large processions, the building of triumphal arches and other ways of emphasising the acceptability of the Emperor to his people.] To enhance his position, Claudius rejected an invasion of Mauretania [northern tips of Morocco and west and central Algeria, subsequently conquered in AD 44]. He chose instead the conquest of Britain as his goal. Rome desired Britain’s surplus grain as well as its metals of lead, iron, tin, copper, gold, silver; also its hunting dogs, pearls, animal skins, and natives who could be sold as slaves.

In Britain the powerful Cunobeline, head of the Catuvellauni tribe, had died around AD 41. He left two sons, Togodumnus and Caratacus. Togodumnus took over his father’s lands to the north of the Thames. His younger brother Caratacus moved away and conquered almost all of the area south of the Thames. Caratacus also demanded allegiance from the Dobunni. The death of Cunobeline had thus resulted in two kings controlling much of the southern half of England. They both disliked Rome.

Verica became king of the Atrebates tribe in about AD 15. Occasionally he has been called Berikos but historians assume that Berikos and Verica were the same person. In AD 42 Caratacus conquered the Atrebates so Verica, an ally of Rome, went to the Emperor Claudius to seek support. Verica reported that Britain was in a state of rebellion. This gave the Emperor an excuse for invasion and thus the expected award of his “triumph”. [As Clausewitz says “No one starts a war without first being clear in his mind what he intends to achieve by that war and how he intends to conduct it”.]

The Roman Army that invaded Britain in AD 43

Aulus Plautius Silvanus was in command. Prior to this appointment, he had been the Governor of the Roman province of Illyricum, a large area comprising some of present-day Romania, Serbia, Albania, Bosnia, Croatia and Hungary. He thus had much experience of provisioning forces using sea and river transport, a tactic that would be essential during the invasion of Britain. His deputy was probably Servius Galba who was a very senior commander and had just been Governor of Upper Germany. [In AD 68 at the end of his career, Galba became the Roman Emperor.] Suetonius, possibly writing some 60 years later, stated the invasion of Britain was postponed due to Galba’s “slight indisposition”.

The Roman army rendezvoused in the spring of AD 43, but where? It has been suggested that it assembled near the Rhine estuary but it seems more likely that Boulogne area was the chosen location. The French coast is nearer Britain and thus the sea crossing would be an easier and shorter problem for Plautius. The Army would have needed to be self sufficient in food and forage as little could be expected to be found in Britain at that time of the year.

Four legions marched to Boulogne to take part in the invasion. Each legion consisted of some 5200 men and comprised 10 cohorts. The first cohort was the elite and had 5 centuries, each of 160 men. The other 9 cohorts had 6 centuries, each of 80 men. Each century was divided into 10 sections each of 8 men. A legate commanded each legion, assisted by 6 tribunes. The first three legions were spared from the Rhine area where no trouble was expected from the native inhabitants. They were:

• II Augusta who came from Strasburg,

• XIV Gemina from Mainz, and

• XX Valeria from Cologne.

• The fourth legion, IX Hispana, came from Pannonia, in Hungary, where their fortress may have been at Sisak and where they served under the Army commander. Like Plautius, they were thus experienced in the use of boats for movement and resupply.

Based on circumstantial evidence, it has been suggested that the invasion force may also have included a detachment from VIII Augusta stationed at Poetovio, also in Pannonia.

There were many auxiliary troops and supporting services too; for example cavalry, archers, bridge builders and the Batavians, based in Holland, who specialised in making river crossings wearing full equipment. The invasion force was some 45,000 men. [Some books give 40,000; others 45,000; one 50,000.] The troops comprised mostly light infantry, heavy infantry and cavalry. Apart from the four legions, the other half of the Army would have been auxiliaries from conquered countries. [They would usually be awarded Roman citizenship after 25 years of Army service.] The auxiliaries would take the lead role, going ahead of the main army to find the enemy and then taking the front line in any fighting.

The invasion was delayed as the troops mutinied due to fear of the “ocean”, repeating the experience of Caligula around AD 40. Surprisingly one book believes this mutiny is a myth. I reject this view as Dio mentioned the event. Twice during the campaign (see below), I believe the Army commander decided that his other three legions were more resolute than XX Legion. Perhaps it can be deduced that XX Legion started the mutiny and this caused Plautius’s concern as to their reliability.

To quell the mutiny, Dio wrote that Claudius sent his senior minister, the ex slave Narcissus, to Boulogne. Using his wit and wits, Narcissus persuaded the Army to embark. Once the troops had agreed to invade, no doubt there would have been suitable sacrifices to Jupiter and Mars, the Roman gods of weather and war respectively.

Roman legionaries crossing the River Medway: Battle of Medway June 43 AD in the Roman Invasion of Britain: picture by Cecil Doughty

PART TWO – THE INVASION OF AD 43

Where did the Romans invade?

There have been two suggested areas for the invasion location: Richborough in Kent and Bosham in Sussex. Several historians believe that the main force landed near Bosham where Britons lived who were friendly to Rome. I accept the majority view that the landing place was Richborough in Kent. I have nine reasons for this. In chronological order:

First, Julius Caesar had successfully come ashore on the sloping beach at Richborough in 55 BC, on a reconnaissance visit. Although a few days later there was a large storm which scattered his navy, he persisted with Richborough and again landed there successfully a year later for his brief invasion of Britain. It would have taken a rash Roman commander to try something different, although the seashore would have changed a little in 97 years.

Second, after the mutiny in Boulogne, it would have been essential for morale for the sea crossing to be as short as possible. The shortest sea crossing was from Boulogne to the cliffs at Dover and then north until a suitable landing place was found. An invasion at Bosham would have required a long and dangerous voyage for an army and navy of some 45,000 men who had recently mutinied due to fear of the “ocean”.

Third, in September 2008, English Heritage archaeologists found evidence at Richborough Fort of Roman ditches that they believe show the invasion landing place.

Fourth, there is a small hill at Richborough that allows good views of the nearby open countryside. Sentries would be able warn the invaders of a surprise attack by the natives. Such a geographic feature was important in those days to allow the army commander to make informed decisions before and during a battle.

Fifth, and most important of all, a landing at Richborough allowed for a military advance towards London to be shielded by the protection of the south bank of the River Thames. With the Romans attacking due west, the British would be limited to defending north-south positions (e.g. the rivers Stour and Medway) and harassing the Roman Army from southern woodlands. An invasion at Bosham would have meant a far riskier advance to London. That countryside would offer the Romans no natural protection from the British forces who would know the ground. The Romans could thus be attacked from all directions.

Sixth, use of the River Thames would offer a much simpler and safer method of resupply to an advancing army than a land-based operation.

Seventh, the latest of the gold coins found at Bredgar (described above) is dated AD 42.

Eighth, II Legion was present at the major battle of the campaign, widely assumed to be the crossing of the River Medway. II Legion is most unlikely to have landed at Bosham and then fought its way to the Medway using a very circuitous route so as to be on the east bank for the battle. (It has also been claimed that the major battle was over the River Arun at Pulborough, Sussex but this doesn’t conform to the description left to us by Dio. The only defensive feature there was a river that was shallow, slow moving and only 60 feet wide. This would provide minimal difficulty for an opposed river crossing by the Roman infantry. A large British force is most unlikely to have attempted to defend such a poor position.)

Ninth, a large arch was constructed at Richborough around AD 80, another indication that the invasion started there, not Bosham in Sussex.

Arrival of the Roman Army and its initial progress

Dio wrote that the Roman troops were sent over to Britain in three groups. Historians are uncertain of the meaning of this statement. Some ignore it, as it was written around 150 years after the event. A suggestion is that the Romans arrived in three divisions, i.e. that the force had three distinct tasks. Others historians consider it means there were three widely-spaced landing places. This seems to me unlikely, as it would have been important to concentrate the invading Army for command and control purposes.

It has not been widely suggested, but perhaps it should have been, that the landing took place in three waves, over a period of at least a week. The strength of the Roman Army was some 45,000. Such a large body of men would have been very difficult to co-ordinate at Boulogne, organise at Richborough and also replenish. There were animals involved too. One historian believed that 10,000 baggage animals would have been needed.

One military historian has computed that the Romans would have needed at least 933 ships. This would have meant a huge shipbuilding programme somewhere on the north European coast. If the landing had been in 3 widely-spaced waves, as I suggest, the number of boats needed could have been reduced by some two thirds, as most boats would be used on three occasions. Feeding such a large army of men and animals before the autumn harvest would have presented a huge logistical problem. Arriving at Richborough in three waves over several days would have been easier for command and control of men and materiel.

Perhaps:

- The first wave consisted of 2 full legions and some auxiliaries, together with most of the command structure;

- The second and third waves each contained another full legion and half of the remaining part of the Army, mostly auxiliaries.

Dio described the sea voyage as difficult but wrote that the landing was unopposed. The exact geography of the area 2000 years ago is uncertain [although there is currently a helpful chart on the south bank of the River Stour, just east of Upstreet] but Richborough was then on the seashore where it met the estuary of the River Stour. It was a natural port. I believe the landing place was near Grid Reference TR322600.

A British force may have been waiting on the Kent coast, say at Dover, expecting an April invasion. Traders routinely crossing the English Channel would have brought news of the Roman mutiny. Most of the British force would then have dispersed, having run out of food, and returned home to work on their farms. A few observers would have remained at Dover to report any important activity. By chance then, the invasion met no initial resistance.

East Kent in AD 43 was very different to its shape today: for example the Isle of Thanet was truly an island; the River Stour was in places one or two miles wide; much of the area was waterlogged. It seems likely that the invading force moved westwards on firm ground near the south edge of the waterlogged area. Thereby the right flank of the Roman Army would be protected from attack. Their route was not along either the current “Saxon Shore Way” or the “Stour Valley Walk”. In AD 43 these modern river walks would have been under water.

Trackways that existed before the Roman Conquest are described as “prehistoric”. They were routes that missed bogs, were not too hilly and remained dry in most weathers. Often the best path closely followed the top of a ridge [remember the final images of Ingmar Bergman’s film “The Seventh Seal”?]. On parts of the current “Stour Valley Walk” and the “Saxon Shore Way”, the ground on one side of the levee is much lower than the river itself. Also there are now lots of ditches to drain the farmland. The Romans could not have gone in these directions. Close to the modern A257 seems to me to be the probable route for the invading forces, along the bank that ran beside the river as it was in AD 43.

Dio reported that Plautius had difficulty in finding the British, who refused to engage in close combat but instead retreated to the marshland and the forests. After an unopposed landing, Plautius would have sent some auxiliary cavalry southwards, towards Dover, to act as a protective screen for his main advance. [In 55 and 54 BC Julius Caesar also landed near Richborough. In 54 BC his Army then marched to Canterbury and conquered a British hill fort. This was probably in Bigbury Wood near Harbledown, 2 miles west of Canterbury.]

First contact between the Armies in AD 43

The brothers Togodumnus and Caratacus of the Catuvellauni tribe commanded the British force. They controlled most of the southern half of England as I have shown above. One military historian has estimated that the British force could have been as much as 150,000, with support coming from all the tribes controlled by the brothers. I am happy to accept this figure. The British force may well have assembled initially in the spring of AD 43 and then mostly dispersed on hearing of the mutiny by the Roman Army at Boulogne. Nevertheless some of the British force would have remained to act as a “tripwire” in the event of a later invasion. The two brothers commanded their force using messengers travelling swiftly on horseback.

There were initial skirmishes at Canterbury where the River Stour was fordable. The British were trying to hinder the Romans. Through this delaying tactic, the other British groups would have more time to travel from all over the land to prepare their main defensive position. This is widely assumed to be along the west bank of the River Medway, as there seems to be no possible military alternative.

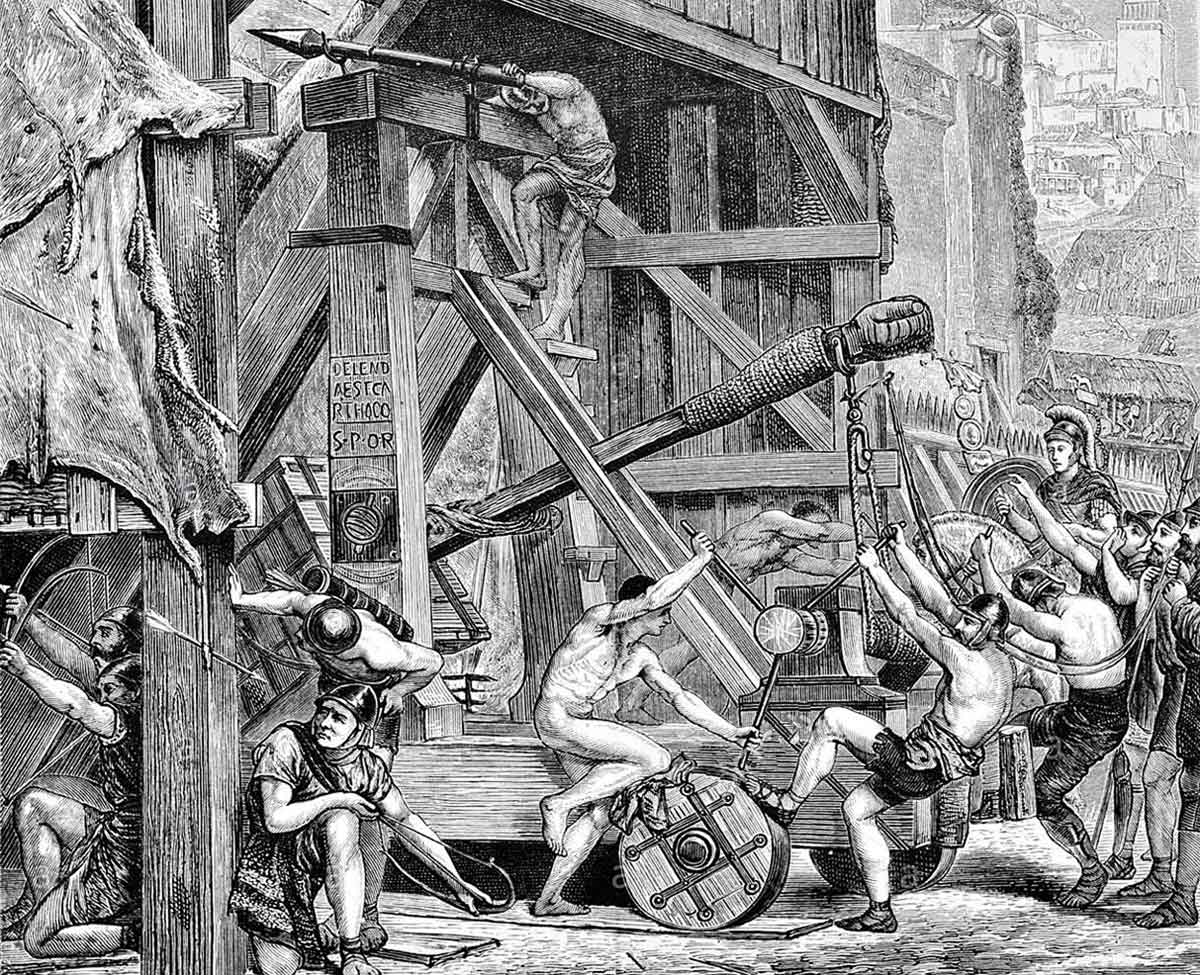

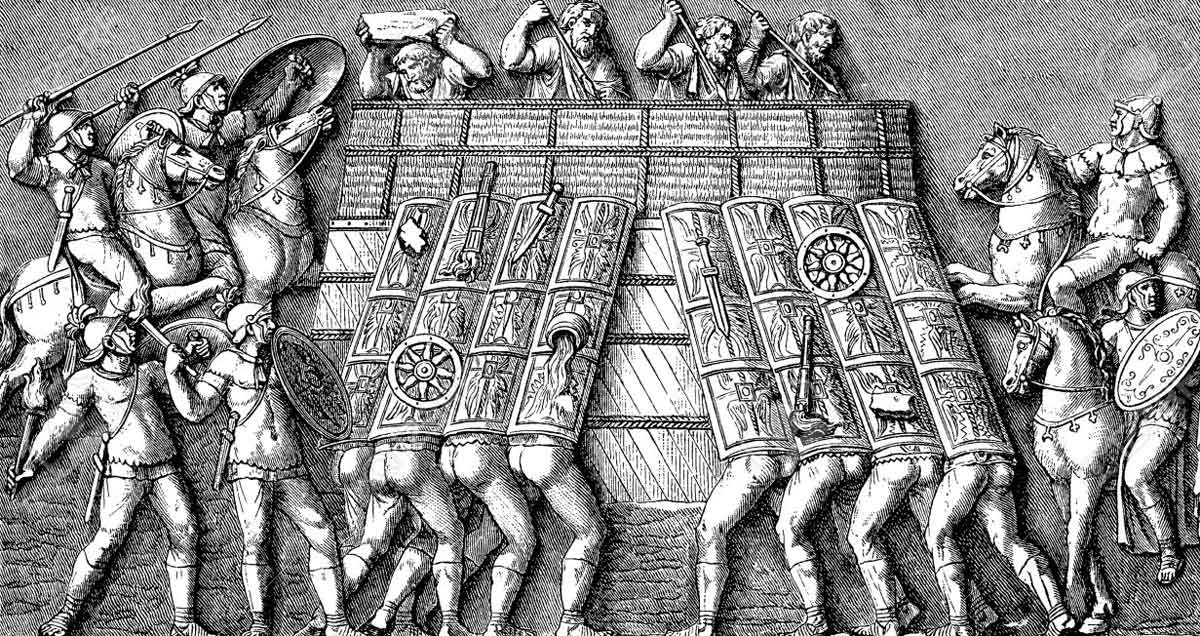

Roman legion standards on Trajan’s Column: Battle of Medway on 1st June 43 AD in the Roman Invasion of Britain

Canterbury was the tribal base of the Cantiaci and they defended their homeland. There is confusion however over the name of a second group of tribesmen who were left to delay the Roman forces whilst the main British force was being assembled. Dio called them the Bodunni but historians correct Dio and state the tribe Bodunni was in fact the Dobunni.

Many Dobunni lived near the Severn basin. Their contribution to the British force would have taken several weeks to make the journey to east Kent, in anticipation of a Roman invasion in April. The Dobunni warriors had thus travelled a long distance that spring. On hearing news of the Roman mutiny, the Dobunni segment of the British force was therefore the obvious group to remain in east Kent to help delay the invaders, rather than return home.

The local tribe of Cantiaci occupied its own land. They had been friendly to Rome for a long time and would not have had the determination to fight for long. Thus the small number of British defenders at Canterbury soon surrendered or fled, allowing the Romans to cross the River Stour before moving westwards to come upon the main British defensive position on the west bank of the River Medway.

A small Roman garrison would have been left at Canterbury to build a fort. This might be needed as the basis for a defensive position in the event of a major British victory resulting in a Roman withdrawal. The site of the fort has never been found but it must surely be on the west bank of the Stour protecting the ford, wherever that was. [Some Roman artefacts have been found close to the site of the Norman Castle.]

Roman progress towards the River Medway

It was normal practice in the Roman Army for auxiliary forces, usually on horseback, to go ahead of the main force as a vanguard to scout for problems. This protection of the invaders would certainly have happened in AD 43 as the countryside was wooded. The vanguard would clear out small parties of enemy to the front and sides. They also gave warning of any major enemy fortification or force. The British forces, having been recalled from many parts of the country, would need an obvious location to rendezvous. This was almost certainly the west bank of the River Medway. Small numbers of British probably harried the Roman Army to delay further its arrival at the east bank of the Medway. This delay allowed the British force to enlarge, spread out along the west bank and become more co-ordinated under the brothers Togodumnus and Caratacus.

Historians disagree about the route taken by the Romans from Canterbury to the Medway. They could have followed the dry, high ground and long established route of the Harroway. This was a prehistoric trackway, now known for an early section as both the “North Downs Way” and the “Pilgrims’ Way”. [The Harroway is said to be the oldest prehistoric trackway in Britain, having been used for at least 6000 years. It goes from Dover in an arc across the high ground of southern England to Marazion near Penzance.] From Canterbury, the “North Downs Way” initially goes southwest before turning westwards, north of Ashford. Most historians believe this was the route used by the invading Army. Resupply of an army using this route to the Medway, however, would not have been easy. A very long column spread out along the “North Downs Way” would be vulnerable to British skirmishers from all sides.

Other experts think the Romans followed closely to the future line of “Watling Street” [which was thus named by the Saxons but is now called the A2]. There was a settlement at Rochester of Belgic immigrants. It is thus very probable that there would have been a recognised direct path between the Cantiaci capital at Canterbury and the settlement at Rochester. Romans using the “Watling Street” route could be easily resupplied from boats travelling along the River Thames.

My military view is that both these opinions are wrong. The Roman Army advancing to the Medway numbered around 45,000 troops. (A few would have been left in the rear to guard important points and assist resupply.) It seems unnecessary and unsafe to have such a large force travelling mostly in single file along either the “North Downs Way” or “Watling Street”. The obvious solution to me is to use both routes and other tracks as well, so as to advance on a broader front. All the British would thus be forced to retreat.

Bredgar is a tiny village south of Sittingborne where in 1957 there was a find of Roman auri gold coins. [Very strangely the references differ as to the date and the number of coins found. Some give the date as 1958. A few state 37 coins but most give the number of coins found as 34. Thirty four auri was a quarter of the annual wage of a centurion; a legionary was paid 9 auri per year.] Of the Bredgar auri, the latest is dated AD 42. Thus the find is thought to be the life savings buried by the owner, maybe a centurion, as he was about to be sent on a dangerous mission as part of the invasion in AD 43. Bredgar is almost 11 miles east of the Medway. “Watling Street” is a little over 2 miles north but the “North Downs Way” is twice as far away to the south. The find seems to show that at least some of the Army passed through Bredgar, which is on the north edge of a ridge, probably with an east-west path along it, as well as using “Watling Street” and the “North Downs Way”.

So it seems probable to me that the Roman Army was split with most of two legions and the command structure going along “Watling Street”. The Army commander would have been here to aid liaison with the Roman Navy and so as not to expose himself to unnecessary risk. This route would have the defensive advantage of the River Thames to the north, preventing an attack from that direction and also giving ease of resupply from the river. One of the two legions with Plautius would have been IX Hispana, as they were experienced in the use of river transport. The other was probably XIV Gemina for reasons connected with the Batavians. (These are explained below) I think the remainder of the Army travelled in the same general westerly direction but a few miles to the south. Probably most of the other two legions used the “North Downs Way” and mounted auxiliaries swept the ground between the two pairs of legions. This would certainly have happened if the Roman vanguard auxiliary had found that minimal British resistance was expected at this stage of the invasion. Probably some infantry used east-west footpaths between the two routes; this could explain the existence of the Bredgar coins.

It is likely that II Legion, under its legate Vespasian, travelled along or close to the “North Downs Way”. By using this route, they would be towards the left of the line on arrival at the edge of the river. Their part in the battle, as described by Dio, shows that they were indeed on the left of the line for the crucial assault across the river, widely assumed to be at the River Medway. (See below.) There are two scenarios for II Legion getting to this position: first that they marched along “Watling Street” and were then reassigned on the left of the line, or second that they marched with the “North Downs Way” contingent, in which case they would be on the left anyway. The former requires unnecessary turbulence and would alert the British to the likely location of the Roman attack. Hence my view that Vespasian travelled close to the prehistoric Harroway, now known as the “North Downs Way” or “Pilgrims Way”.

Suetonius, writing around the turn of the first century, says a great deal in his book about Vespasian who by then had been dead for some 20 years. From contemporary busts and coins, we know he had a big, jowly face with a large nose and a protruding chin. It is the face of a man of action. Suetonius described Vespasian as strong, well-formed but with a strained expression on his face. He was proud of his poor origins; his father had been a tax collector. Suetonius said he was modest and restrained in his conduct of affairs and disliked outward show. He was nearly always good-natured, cracking jokes but with a low sense of humour. When Emperor he was known to be just, respected but mean over money. As he lay dying his last words, humorously, were “Dear me! I must be turning into a god”. (Vespasian was one of those few emperors who were promoted to be a Roman god by a successor; in his case by his elder son, Titus.) Vespasian was a soldier’s soldier!

Faversham

There may have been a temporary camp established at Faversham by that part of the Roman Army that followed the route of “Watling Street”. [A Roman legion stopped every night to build a temporary marching camp of a standard pattern. Each person had a set task to aid speed and efficiency. Each camp was surrounded by a rampart and ditch.] The ground to the west of the B2045 from Oare Creek to the modern Syndale Motel (GR TQ994609) is low lying. In ancient times the Creek finished closer to the current position of the Motel. Any Roman camp here would have been resupplied from boats coming up the Creek.[There has been a Channel 4 Time Team programme about the work led by Dr. Paul Wilkinson near the Syndale Motel. All but one of the Time Team trenches were to the west of the Motel. Time Team found evidence of a lot of Roman activity nearby, including a coin minted in Rome between 41 and 42 AD. Nevertheless Time Team deduced there had never been a Roman fort on the west side. A fort needs a ditch, rampart and many guards to provide very good protection. A few months after the Time Team visit, I went on Paul Wilkinson’s weekend archaeology course and was directed to dig to the east of the Motel. On 13 July 2003, I found the base and the bottom fifth (intact) of an early first century Samianware cooking pot and some large animal bones, all about 4 feet below the surface. This piece of broken pottery and the bones would have been thrown into the ditch on completion of a meal. The ditch had subsequently been filled in using the soil from the defensive rampart. It is even possible that, several weeks after the events of the invasion described above, the Emperor Claudius was rowed or sailed up the Creek for a temporary camp. He might then have returned down the Creek on his way to the Thames and London to meet up with the waiting Army. This would have been a safer route and more comfortable than riding on horseback from Richborough. Protected by the ditch and rampart at Faversham, this could have been where he spent his first night on English soil!]

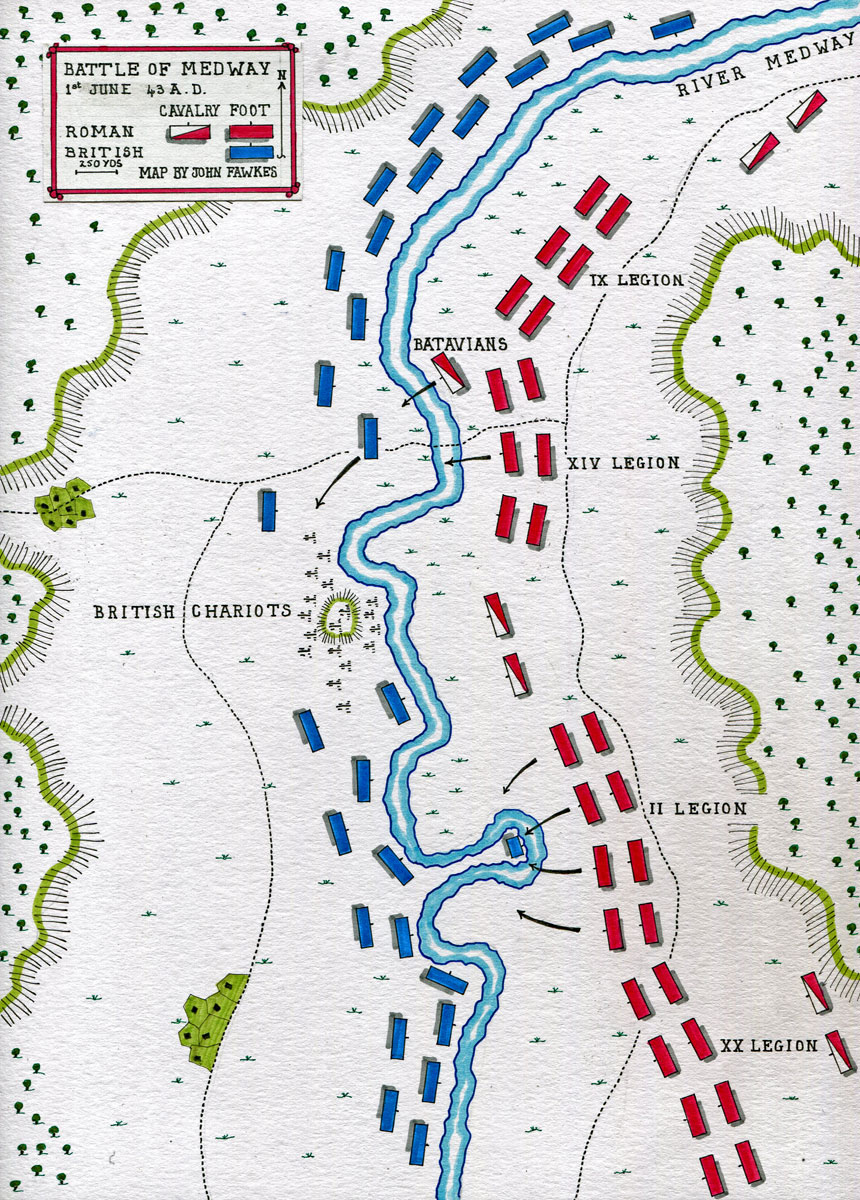

Battle of the Medway

Military Situation

The river was far too tidal and wide at Rochester for a battle to have been fought there. I think the British commanders, the brothers Togodumnus and Caratacus, would probably have established their Tac HQ [Tactical Headquarters – the commander’s small decision making group] on the prominent high ground overlooking the river just south of Halling at GR TQ708635. The Main HQ [the remainder of the support function of the British force] was possibly then sited in the lower ground near GR TQ704639.

The Roman commander, Plautius, would have studied the ground during his reconnaissance. The best views of the Medway valley are obtained from the ridge between GR TQ727654 and GR TQ733627. From here he would also looked across the Thames Estuary towards the flat marshes of Essex. His legions were probably located as follows:

• IX Legion was very probably closest to the Thames as it was experienced in operating with the Roman Navy, i.e. it was on the right of the line.

• XIV Legion was probably immediately south of IX Legion, in the right centre, with the Batavians in case they were needed for a river crossing. The Batavians were auxiliaries, within the Roman forces, who were trained to swim across rivers in full equipment. [It is known that by AD 67, the Batavians were attached to the XIV Legion Gemina, so I’m assuming they were part of that Legion in AD 43 too.]

• During phase 2 of the Battle (see below), II Legion was one of the two Legions on the left of the line as it initiated the successful crossing of the Medway upstream. One of the factors that Plautius would have considered in choosing the attacking legion would be a wish not to leave his left flank exposed, so very probably II Legion was positioned in the centre left.

• This deployment leaves XX Legion covering the left flank of the Roman Army.

According to Dio, there were four phases of the Battle:

Phase 1 – The British lose many horses

Chariots were important to the British. These were used to intimidate the enemy and send the best British fighters quickly to the position where they could be most effective. Small horses were also used to bring reinforcements.

It is often military practice to confuse the enemy by pretending to be attacking some point away from the actual place of assault. I’m sure this happened at this battle. [An example is the feint concerning D-Day, in 1944, of the Allied forces pretending to have the intention of crossing the Channel from Kent.] Perhaps the preparation for the Roman dummy attack took place just to the south of Wouldham Marshes, say around GR TQ712630.

Dio stated that the Battle opened with the Batavians using their skill of swimming across rivers in full equipment. They probably went a little downstream where the current was slower and where a ford may have existed. Then, out of sight of the British Tac HQ, they crossed the river and surprised the natives in the British Main HQ. The route of the Batavians might have been from GR TQ713644 to GR TQ711643, then along the firm ground, now a track, across Halling Common to GR TQ704639. I reject the view of the military historian who stated the Batavians crossed the river well to the north at GR TQ735677 towards Temple Marsh, first because the land may well have been marshy and second that the river here would be too wide and tidal.

Then the Batavians attacked the British rear and wounded the horses that pulled their chariots. British morale would have been affected by the loss of their horses and the realisation that the Romans had easily crossed the tidal river. Strategically, the British charioteers were now forced to become slow moving infantry.

Phase 2 – Vespasian’s plan

The British force was spread out thinly along the whole riverbank, now with fewer horses and not knowing where the main attack would come. With four legions at his disposal, Plautius would have sent one to attempt to make the initial river crossing. He chose II Legion, led by Vespasian. If its attack failed, then an attempt would be made by another legion. Vespasian’s first task was to decide on a crossing place for his attack. He would have had to look upstream for somewhere easily fordable by his troops.

Vespasian would have found several possibilities for a river crossing. I reject the view of the military historian who stated II Legion crossed the river at GR TQ713644. I believe the thrust was further upstream where the river is narrower and less tidal. On the advice of local historians, there is now a large stone commemorating the Battle of the Medway at GR TQ709618 and this is possibly the site of the prehistoric river crossing point of the Harroway from East Kent to Guildford and beyond. There was a ford at Aylesford at GR TQ728589 but the most likely location for the attack seems to me to be from all around the curve of the riverbank at GR TQ715620. This is a good place to cross as the river is wider at the bend, and thus shallower and less fast flowing. Above all, having crossed the river, the Romans would attack a virtual island. Having taken this “island” at GR TQ714619, possibly at dusk, the surrounding water would have made it easier for Vespasian’s Legion to defend the position against the expected British counter attack.

Vespasian as Emperor of Rome by Rubens: Battle of Medway on 1st June 43 AD in the Roman Invasion of Britain

Phase 3 – Vespasian’s attack

Under my scenario, the crossing was made, the “island” taken and Vespasian may well have then established a small bridgehead on the far bank, south of Snodland. Some historians suggest that two legions were involved in the initial river crossing. From a military point of view, this does not seem likely. An initial attacking force of two legions, each of 5200 men, would not have been necessary or practical given the size of the river. [The standard military method of war is for one formation to attack, take and hold a position, whereupon a second formation moves through the first’s position to attack and hold its own objective. It is a leapfrog movement.]

Phase 4 – The British are defeated

Dio said fighting continued into a second day. This was unusual for a Roman battle but the result was that the Romans had a total victory. Almost certainly this happened following a breakout from Vespasian’s position by a second legion attacking northwards on the west bank of the river. XIV Legion was probably given this task, as after Vespasian’s attack on the previous day, my order of battle (see above) shows XIV Legion now in the centre of the line on the east bank. The Legion in the centre would have been the correct formation to ford the river next, leaving IX and XX Legions continuing to cover the right and left flanks respectively.

The objective of XIV Legion would have been the British positions near Halling. The river protected the right flank of the attackers. It is recorded by Dio that Gnaeus Hosidius Geta was awarded the ornamenta triumphalia for his achievements in the battle. We can deduce he was the legate who commanded the attacking XIV Legion. His Legion probably forded the River Medway at dawn on the second day, and moved through Vespasian’s position to attack northwards. This resulted directly in the British defeat and withdrawal.

One military historian has claimed that Geta was the Army second in command, whereas most accept that this was the future emperor Galba. The same historian also states that Geta’s Legion took over the attack from Vespasian. These statements seem contradictory. I accept the second statement but not the first. The same historian also believes Geta’s Legion was XX Valeria. Again I disagree, as I contend that XX Legion was on the east bank throughout, being used to protect the crossing point.

Vespasian had an elder brother, Flavius Sabinus, who was also in the invading Roman Army. [Lindsey Davies has written an enthralling historical novel about the two brothers.] Dio stated that Sabinus was a staff officer under his younger brother but, in view of Sabinus’s seniority, most historians consider this to be a copying mistake. Certainly Sabinus played a part in the battle. There has been speculation that Sabinus too was a legionary commander and that Vespasian’s Legion was accompanied in the initial crossing by another legion commanded by his elder brother. This doesn’t seem possible, as the two legions would have got in each other’s way. I believe Vespasian served under his elder brother as this seems much more probable. Perhaps Sabinus, as a staff officer, first coordinated the two attacking legions of Vespasian and Geta and then controlled the crossing point generally when the rest of the Roman Army moved across to the west bank of the River Medway.

After Geta’s XIV Legion had moved through Vespasian’s location on the “island” to attack the main British force towards Halling in the north, another legion probably then moved through Vespasian’s position also. This third legion arriving on the west bank was probably IX Legion, leaving XX Legion on the east bank to continue to protect the left flank, as any surprise British attack on the east bank would come from the south. Strategy would dictate that the weakest of the four legions would be allocated this least aggressive role.

As XIV Legion advanced, taking on the brunt of the British force, IX Legion would then protect it by defending the ground immediately to the west and south, thus preventing any British skirmishing at Geta’s rear. Finally the remainder of the Roman forces would have crossed the river, possibly by a quickly erected bridge at GR TQ709618 where the river is relatively narrow at low tide. A bridge would consist of a walkway on floating boats.

The final British stand may have taken place on the prominent high ground overlooking the river, just south of Halling at GR TQ708635. This seems the probable location of the British Tac HQ throughout the battle. The British would naturally have fallen back to the best defendable position. Togodumnus was killed in the fighting, or died soon after. Perhaps it had been decided that he should lead the last stand whilst his brother Caratacus left the battlefield to regroup the remaining British forces and fight another day, as described later.

As it led to 400 years of Roman rule, with its legacy still seen today, I believe the Battle of the Medway AD 43 was one of the two most significant battles in British history, along with Hastings 1066. Those who study the website britishbattles.com can debate this!

Actions after the Battle

One military historian, and others, have suggested that the British did not retreat towards London but instead went northwards and crossed the Thames to arrive in the East Tilbury marshes. This idea seems wrong, not least because the same historian has suggested that the original British force was as many as 150,000. It would surely have been an impossible logistical exercise for many retreating tribespeople to cross a tidal river here, whilst being harassed first by the Roman cavalry and then the Roman Navy. Few of the British would have been expert swimmers and there could not have been many boats available. Dio, writing 150 years after the event, mentions that the British forded the river with ease at its mouth where the river became a lake at high tide. It is difficult to imagine fording with ease to East Tilbury, GR TQ690764, where the river is currently 1300 metres wide. So, based on Dio, I believe the British ford was higher up the River Thames.

Roman legionaries on Trajan’s Column: Battle of Medway on 1st June 43 AD in the Roman Invasion of Britain

The River Thames had a different shape in AD 43 from now. (For example the Museum of London makes a number of statements. “Near where London Bridge currently stands, the River Thames in AD50 was about 300 metres wide [compared with 100 metres today]. There was a ferry crossing at this point. [The first Roman bridge here was built around AD 85]. The river was tidal here with a minimum rise and fall of 1.5 metres.”)

For the Romans, the next strategic goal was to find somewhere to cross the Thames safely as a first step towards the base of the Catuvellauni at Colchester. [Throughout history, conquest of an enemy’s capital has usually been the main goal of an invading army. Destruction of the administrative base leads to chaos and an immense drop in morale.]

Having won the Battle of the Medway, the Romans would have followed up quickly by killing as many of the retreating British troops as possible. This was a task normally done by the auxiliary cavalry. Their objective was to kill enemy soldiers so they were no longer a threat to Rome. The four legions followed, probably in the following order of battle:

• The main part of the Army would have gone towards the chosen crossing point of the Thames, assumed to be in or near London, in a northwest direction by the quickest route (Cobham, Gravesend, Dartford etc.). Probably XX Legion would have led the way towards the crossing point. It had played a minimal part in the battle and would be fresh. XIV Legion would have followed so as to give it the best chance of recovery after its hard fighting in conquering the British forces towards Halling.

• It seems likely that IX Legion with its experience of river work would have gone north along the riverbank towards Strood covering the right flank of the advance. For this part of the advance, the Batavians were probably attached to IX Legion so as to be easily available if required.

• This leaves II Legion on the left flank to control the wooded country westwards. Vespasian would have developed experience in this role during the earlier advance to the Medway, when I believe II Legion travelled close to the “North Downs Way”.

British chieftains on the march: Battle of Medway on 1st June 43 AD in the Roman Invasion of Britain

The Roman support element would have quickly built a bridge at Rochester to get food, fodder and materiel originating in France forward to the fighting troops. This would have been a floating bridge with wooden spars on top of small boats tied together. Nevertheless because of the strong action of the local tides and the width of the river at this point, this type of structure would not have been easy to construct. [There is a model of a Roman assault bridge in the first room of the Royal Engineers’ Museum at Brompton.] Of course until the Roman road “Watling Street” was built, most supplies for the Army would be transported up the Thames by boat.

The next piece of civil engineering would have been the improvement of “Watling Street” from Richborough to London. The building of a Roman tactical road started only a couple of days after the forward legion had moved through the area. The engineers were given protection whilst they worked. The road would facilitate communications and the moving of materiel up the supply chain to the forward areas. [To provide straight roads Roman Army engineers cleared routes through woodlands, created firm ways across marshes and soft areas with log foundations, and built timber bridges where necessary.]

It is theoretically possible that II Legion detached itself from the main force at this point, without travelling towards London. This could have happened if the British resistance in Kent was over or if it was deemed essential to get to Chichester very quickly to establish a port without delay for the resupply of II Legion. In this scenario, II Legion’s route might then have been initially along the Harroway, the trackway now called the “North Downs Way”. They would have left the prehistoric path at Dorking or Guildford and gone direct to Chichester. However because the main purpose of the conquest was to create a “triumph” for the Emperor, it seems to me much more likely that Plautius would opt for safety and take all his four legions with him through the unknown countryside and towards London.

Crossing of the River Thames

The British had retreated to the north bank of the Thames. The Batavian cavalry had fought well in the first phase of the Battle of the Medway by swimming across the river in full equipment. Dio said they performed a similar role here. The Roman Army then crossed the Thames by a bridge a little further upstream, as Dio also described. Roman sources give no indication of a large battle at this stage of the invasion. This suggests that the crossing of the Thames was essentially unopposed, as the British had given up the unequal struggle. The building of a bridge could only have been achieved if there had been minimal opposition. The bridge site may have been near the current location of London Bridge or Westminster or even at Brentford, although the latter seems a long way to the west.

Dr Hugh Chapman believed that the Roman Army’s bridge was at Southwark where he supervised large scale excavations in the 1970s. Based on the island then in the middle of the river and other indications, Channel 4’s Time Team decided however that the Roman bridge was near Westminster. Their reasoning is helped by both “Watling Streets” (the A2 and the A5) meeting at Westminster, when extended west and south-east in straight lines.

Caratacus appears before Claudius Caesar in Rome after the Battle of Medway on 1st June 43 AD in the Roman Invasion of Britain

It was probably at this time that Caratacus realised that the south east of England was a lost cause. This included his family tribal base at Colchester. This was due to the might and organisation of the Roman Army that had defeated the British at the Battle of the Medway. He therefore went northwest with his forces towards the Druid base on Anglesey, possibly basing himself first at Minchinhampton, near Stroud in Gloucestershire. [Fighting in the northwest between the Roman invaders and the remnants of the British force continued for another 8 years. In AD 51 Caratacus was captured and taken to Rome. (This is according to Tacitus who was writing approximately 50 years later.) Claudius then organised a large parade to emphasise his power in overcoming an important barbarian. Caratacus was then given a pardon and a pension. He lived his last years quietly in Rome. Readers may remember a scene in the BBC TV “I Claudius” with Peter Bowles playing Caratacus.]

Send for Caesar!

Returning to the summer of AD 43, having crossed the Thames in London and established a small bridgehead, the invasion was halted so that Claudius could come to Britain to “earn” his “triumph”. It was necessary to show that the Emperor’s presence was essential for a victorious campaign. The procedure for this had been arranged well before the campaign started. The summons came about by the Army commander, Aulus Plautius Silvanus, deciding [!] that the final battles could only be won with the leadership of the Emperor on the ground, directing his forces. So he sent for Caesar. Dio propounded this political nonsense by stating that the Romans had become entangled in the Essex marshes and this serious opposition required both the Emperor’s presence and also reinforcements, including elephants. It does seem likely, however, that the elephants would already have been waiting for the summons with other supplies in Northern France, or perhaps they crossed the English Channel soon after the Battle of the Medway.

It is said Claudius spent at least 6 weeks travelling to Britain. One military historian has suggested in one place in his book that Claudius’s journey took at least a month longer than this and then later in his book accepts the 6 weeks! Suetonius stated that he arrived having sailed from Boulogne (supporting the assumption above that the Roman Army had sailed from the same port). It is probable that Claudius didn’t land at Richborough. A diversion up the creek to Faversham (see above) would have allowed him to spend his first night on British soil well protected in a temporary campaign camp. He could instead have sailed directly up the Thames from France. So maybe the day after he left Boulogne, Claudius joined the Army waiting for him on the south bank of the River Thames.

It is expected that Claudius would then have carried out a formal review of his Army and a suggestion is that he then crossed the Thames into enemy territory in the lead (which had no doubt been suitably rehearsed!). He then advanced into west Essex. [A work of fiction by Robert Graves imagines Claudius’s visit, including the Battle of Brentwood.] There is the possibility that Claudius did something important at Chelmsford in view of its unusual Roman name, Caesaromagus. The Emperor then proceeded to Colchester to receive the surrender of 11 British kings. The public relations people of the day would have reported this highly prestigious event to the senate in Rome. [For the Romans, important news was quickly communicated with a system of signalling using posting stations on high ground. One such was near Winterbourne Steepleton in Dorset.]

According to Dio, Claudius left Britain after a visit of only 16 days. He then took several months to return to Rome where his formal “triumph” took place in late AD 44. Many celebrations were held. In AD 52, the conquest of Britain was recorded on Claudius’s triumphal arch in Rome.

—

Returning again to the summer of AD 43, well before Claudius arrived in Britain, I believe Vespasian and his II Legion left the main force in London to pursue their separate objective of the conquest of the South of England. There is no historical source for that statement but militarily it seems obvious. II Legion would not have been needed for Claudius’s mopping up phase prior to his arrival at Colchester. This comprised the crossing of the Thames and the small battle mentioned by Dio, possibly at Brentwood [the summit of Brook Street Hill is the best defensive position on the route from London to Colchester].

II Legion’s main objective was to get to Chichester well before autumn. Vespasian had three reasons for this:

• He would have wanted to ensure that he, rather than any British opposition, had control of the harvest of AD 43.

• Autumn storms in the Channel would make resupply and replenishment from France of his force of 8,000 to 10,000 somewhat unreliable.

• He would also have wanted to start planning his campaign for AD 44 well before the winter suspension of active warlike activities.

Below is a summary of my opinion of the possible dates for the AD 43 campaign, so far

The embarkation plan: There seem to be two reasons for believing that mid-April was the earliest possible date for the invasion:

• The English Channel would have been too rough to plan on invading before this.

• The several segments of the large invading Roman Army had to arrive in Boulogne from their various locations. The movement of large forces was unwise in winter in those days due to the wet state of the ground underfoot and difficulties in resupply.

Mutiny: Thus maybe mid-April was the planned invasion date and so Roman strategic planning may have worked towards this. It takes time to organise a force of 45,000 men, their animals and provisions; so possibly the planners thought that a fortnight would be needed before the planned invasion date to prepare for embarkation. So perhaps the Roman Army started to arrive in Boulogne around 1 April. Then the mutiny commenced and, allowing for it to become widespread, maybe it was around 8 April that the commanders realised that there was a serious difficulty. Then they had to decide what to do.

Plautius decided to send message to the Emperor to seek his direction. In response to the message, Dio stated that Claudius sent his chief of staff, the freedman Narcissus, to Boulogne to address the Army. It may have taken around a month before Narcissus was able to persuade the legionaries to give up the rebellion and risk crossing the English Channel. The following activities happened during that period: getting the news of the mutiny to the Emperor in Rome, a short period of consultation and decision, the travelling period of Narcissus from Rome to Boulogne and finally time for him to persuade the Army to comply with Claudius’s wishes. Assuming the weather was calm enough for a crossing of the English Channel, it seems likely that the Roman Army would have embarked soon after Narcissus’s persuasive success, as to delay might have allowed scope for further rebellion.

Batavians: Battle of Medway on 1st June 43 AD in the Roman Invasion of Britain: picture by Otto van Veen

Nevertheless there has been much speculation by historians over the length of delay caused by the mutiny. As examples: “The expedition started on 1 Aug.” “There were months of delay at Boulogne.” “The mutiny had not been a short-term problem and the Army was delayed until late in the summer.” Dio merely used the phrase “made their departure somewhat late”. From the previous paragraphs, I conclude the invasion took place in the early summer.

Around 15 May: This seems the earliest time for the arrival of the first part of the invading Army at Richborough. Others have suggested “late April”, “early July” and “late summer”.

Around 20 May: This seems the earliest date for the relatively unopposed crossing of the Stour at Canterbury. (I know that Julius Caesar in 54 BC reached the Stour only 24 hours after landing, but I think Plautius was more careful as he knew the strength of the opposition. Dio reported that Plautius had difficulty in finding the British, implying delay.)

Around 1 June: This seems the earliest date for completion of the Battle of the Medway.

Around 7 June: This seems the earliest date for the arrival on the south bank of the Thames near or in London at the first crossing point that the Romans found. (I know that Julius Caesar in 54 BC reached the Thames only 2 days after crossing the river Medway, but he had met no serious opposition. Plautius’s Army however had just fought a hard battle and the priority would be to eliminate British warriors.)

Around 12 June: Perhaps the campaign was essentially over by then and the summons was sent to Claudius in Rome to attend the minimalistic battles to establish his right to a “triumph” and consolidate his authority as the accepted ruler of the Roman Empire.

Around 1 July: I surmise that Vespasian and his II Legion left the main force in London to pursue their separate goal of the conquest of Southern England. II Legion would not have been needed for the mopping up phase comprising the crossing of the Thames, the battle mentioned by Dio (possibly at Brentwood) and the conquest of Colchester. [Strangely AD 44 has been given by one historian as the date of the separation but this is surely a misprint, not least as the same person states that the Battle of Maiden Castle (described below) took place in the same year.]

Around 28 July: Maybe Claudius arrived in London. Most historians agree it took Claudius at least 6 weeks of travelling to join his Army following receipt of Plautius’s request [!] for help. Thus I calculate that it took some 2½ months between the Army’s embarkation at Boulogne [middle of May] and Claudius joining up with his Army [late July].

1 August: [Here is another original thought!] This was Claudius’s birthday so possibly he was at Chelmsford and this could account for its unusual Roman name, Caesaromagus.

Around 12 August: Claudius leaves Britain after only 16 days here. His reputation would be greatly enhanced by the conquest of Britain.

By 29 August: It is known that coins had already been minted in Alexandria showing that the Senate had awarded Claudius the honorific title “Britannicus” for his British conquest.

Other suggested dates for the campaign

Some historians say that Claudius arrived in the early winter. I reject this view, as the campaigning season would be finished by then. [For most of European history, all armies were almost immobile from early November to early March inclusive. This was due to bad weather, darkness, lack of food supplies and poor forage for animals. Also wetness underfoot made movement of large forces almost impossible during this period. In the long cold winter nights every effort would concentrate on survival and the eking out of the food supplies from autumn. Armies require many supplies in the field, particularly provisions for troops and animals. These cannot be foraged for 8 months of the year.] Also it seems most unlikely the Emperor would have crossed first Europe and then the stormy English Channel twice in the winter of AD 43 without this being referred to in any contemporary source.

Some historians suggest Claudius arrived a few weeks later than my schedule above but they give no explanation for the coins struck by the Alexandrian mint by 29 August.

Aftermath

Suetonius stated Claudius was away from Rome for 6 months. He is dismissive of the visit of Claudius as “of no great importance … (as) he had fought no battles and suffered no casualties”. On leaving Britain, Claudius presumably spent time visiting his troops in other lands before returning home. Dio said the title “Britannicus” was conferred on both Claudius and his young son. Tacitus wrote that Britain was thereafter gradually reduced to a province of Rome. This can only have been achieved by the gradual subjugation of all tribal groupings. Tacitus also said that by AD 60, London had become an important centre for merchants and merchandise. This can only have happened after the establishment of an adequate road system. This activity would have been a high priority for the conquerors.

PART THREE – VESPASIAN’S CAMPAIGN IN AD 43

Introduction

In his book about Vespasian, Suetonius wrote “On Claudius’s accession, Vespasian was indebted to Narcissus for the command of a legion in Germany; and proceeded to Britain where he fought thirty battles, subjugated two warlike tribes and captured more than twenty oppida, besides the entire Isle of Wight.” (Oppida are defined as towns worth defending.)

Tacitus reported that Vespasian commanded II Legion.

Which were the two warlike tribes that Suetonius says Vespasian subjugated?

Because of all the known battles in their territory (described later), the experts are agreed that one of the tribes was the Durotriges whose centre was in Dorset. Considering the south of England, there seem to be only five possibilities for the second warlike tribe:

• The Dumnonii of Devon and Cornwall. However it seems likely that East Devon up to the natural boundary of the River Exe was part of the territory of the Durotriges, not the Dumnonii. Also Vespasian’s campaign probably finished with the occupancy of Exeter (see below), as he did not see the Dumnonii as a threat. Thus the case seems weak for the second tribe being the Dumnonii.

• The southern half of the Dobunni. As can be seen above, I doubt that II Legion entered Dobunni territory, as the tribe did not live in Southern England.

• The Atrebates. I believe that restoring Verica to the leadership of his tribe seems unlikely to have required a battle. Any forces opposed to Rome, based at Silchester, would have either been destroyed at the Battle of the Medway or fled with Caratacus towards the Druid base on Anglesey.

• The Regini. I also think that there was no difficulty with this tribe at Chichester that merits the word “subjugate”. It had a long history of friendship with Rome.

• The Belgae. On a process of elimination, I conclude that the second subjugated tribe was the group of people based at Winchester.

Vespasian’s strategy for the remainder of AD 43

It is my view that it was at around the first of July AD 43 when Vespasian and his Legion left the main Roman Army in London to pursue its separate goal to conquer the southern part of England. His legionaries may have just spent three weeks in rest, recuperation and a little training after their journey from Dover. Vespasian and his staff would have needed time for the essential military appreciation, planning and briefing. The Legion’s new main objective for the year AD 43 was to establish a fortress and a naval port on the south coast. These tasks needed to be completed before the autumn so that II Legion could be resupplied for the winter. The port was in the Chichester area, at Bosham Harbour.

London to Silchester

Probably the Legion didn’t march directly to Chichester from London. It seems logical that an early task would be for Vespasian to re-establish Verica as the client king of his tribe of the Atrebates based at Silchester. Establishing control of the Atrebates lands to the south of the Thames would enlarge the sphere of Roman domination and show all the British tribes that friends of Rome were treated nobly. From a military view, it would be a sensible tactic to have Silchester under Roman control so Vespasian would know that his rear was protected for the journey south. Certainly the Reading Museum supports this opinion as at states that “in AD 43 the leaders of the Atrebates were restored to Calleva”. [Silchester was the Roman name.] Also Professor Frere states “it is perhaps simplest to suppose that Verica was restored in 43 to be succeeded soon afterwards by a much younger and more energetic kinsman”.

Thus it seems II Legion left the rest of the Roman Army that was awaiting the arrival of Claudius. The Legion’s first goal could have been to establish control of the river crossing of the Thames at Staines. This would reduce the risk of an attack in their rear as they moved westwards. The direct route westwards to Staines is on the north side of the Thames, now called the A30. Vespasian would not have taken this route for two reasons. It would not have provided control of the south bank of the river that formed the north boundary of what I believe was his designated area of operations. Also having a whole legion on the north side of the Thames would have degraded Claudius’s first expected “success” in a few weeks time, that of the crossing of the River Thames, possibly at the head of his troops.

If it travelled towards Staines, Vespasian’s Legion would have chosen instead to move westwards initially by hugging the south bank of the Thames, thus being protected from a surprise attack from the north. Perhaps, having reached Wandsworth, II Legion went direct to Kingston via Wimbledon Common, maybe staying the night in the easily defended location of the Iron Age hill fort “Caesar’s Camp”, Wimbledon, and then crossing Richmond Park. From Kingston the logical route is to follow the south bank of the river to Staines.

From Staines there was a prehistoric trackway all the way along the high ground from Staines to join the Harroway at Farnham. The route from Staines to Silchester, the “Devil’s Highway” [so named long ago as it was thought that anything unnaturally straight must be the work of the Devil], follows this trackway as far as Rapley Lake, near Bagshot. Vespasian could have used this. On the way, the Legion would probably have skirted Egham Hill, which is steep, although this defensive location might have served as a suitable place for an overnight camp. From 1700 onwards, the countryside after Egham was often described in such terms as “desolate” and “mile after miserable mile of open heath”. Vespasian would have had the same view. From north of Rapley Lake, II Legion could then follow the rest of the “Devil’s Highway” which goes in a straight line to Silchester.

Silchester was the base for the Atrebates tribe and an important communication centre. In time, six Roman roads met at Silchester and many would have been based on prehistoric trackways. On the way to Silchester, it is possible to imagine the Legion establishing itself south of Bracknell, at another “Caesar’s Camp”. This Iron Age site at GR SU863657 is an ideal defensive position for a campsite for such a large number of troops. If II Legion went that way, it is probable the main force would have remained at “Caesar’s Camp” while a detachment, possibly only the first cohort of 800 men with a number of auxiliaries, went on to Silchester. Vespasian may have wanted to give the first cohort a specific independent task to see how it operated in conditions of potential warfare.

After consulting local historians in Berkshire, I seem to be alone in my speculation that any Caesar ever went to “Caesar’s Camp”, Bracknell. Perversely I’ll be speculatively consistent and imagine Vespasian also went to the only other “Caesar’s Camps” on the OS map of Ancient Britain. They are near Wimbledon (see above) and Farnham (see below).

[Starting from 400 BC onwards, hill forts such as the three “Caesar’s Camps” mostly ceased to be occupied by the native Britons. Instead the population moved to large defended settlements in valleys known as oppida. These were urban developments. The nearest oppidum to “Caesar’s Camp”, Bracknell was Silchester.] Nevertheless these three Iron Age forts would have made good secure locations, of the right size, where II Legion could have paused on a temporary basis. The countryside was unknown to the Romans and an abandoned hill fort would have made an easily defended campaign fort. Food and water would have been obtained locally.

As he seems unlikely to have encountered any opposition, Vespasian may possibly have arrived at Silchester having taken only a week to travel from London. He would then re-establish Verica as the client king of the Atrebates with due ceremony, and make plans before starting out on the next phase of his route south. I suggest this would take another week bringing the date to around 15 July.

What happened at Silchester was a successful military process continued by II Legion throughout the South of England:

• take control of a tribal area, either by negotiation or battle,

• empower a client British king,

• leave a token Roman garrison behind in the captured area to support the authority of the client king, just so everyone knew who was really in charge,

• move the Legion to its next goal and repeat the process,

• the client king would then maintain order, provide tribute to Rome and supply local recruits to the Roman Army.

[Silchester remained a road centre after the Romans left, at least until Plantagenet times.]

Silchester to Farnham

Perhaps it was now around 15 July AD 43. The essential task remained for Vespasian to establish his port near Chichester before the autumn. The straight-line distance from Silchester to Chichester is 40 miles. The journey was again through a foreign and unfriendly land, so care was necessary. There was a need to establish nightly camps for a force of some 7000 to 8000 men. The provisioning of men and animals would have proved difficult. Allowing for diversions, and maybe a pause at a midway point near Farnham, it seems likely it took at least three weeks to reach Chichester.

It is unlikely that II Legion followed the route of the subsequent Roman road. [This went through Neatham where there was a fort near the River Wey and then on to East Worldham, near Alton. The Silchester – Chichester Roman road consisted essentially of two straight lines with a dogleg at Iping. There was a Roman fort at Iping. I found evidence of an ancient building on the south bank of the River Rother at GR SU848227, almost hidden in the woods, where the Roman road crossed the river north-south. Perhaps this is where a Roman fort might have been expected, but the actual fort is known to have been around GR SU844261. On a separate point, there was a huge find of 29,802 Roman coins in 1873 between Blackmoor and Woolmer Pond.]

Prehistoric trackways had to find routes that missed bogs, were not too hilly and remained dry in most weathers. These ancient routes had been in existence for centuries, if not millennia. They kept to the higher and firmer ground where there were fewer trees and were thus safer. II Legion could not have gone directly to Chichester as later Romans did. Instead they must have followed existing routes, where possible.

Although no record exists, there could have been a prehistoric trackway starting at Silchester and finishing at Chichester. (These two oppida were the centres of the Atrebates and Regini tribes.) It may however not have been suitable however for a force of some 7000 to 8000 Roman soldiers to travel along. Also it seems likely that II Legion would wish to keep well away from Winchester, as this was the base for unfriendly British persons. I thus assume that the detachment of the Legion that had restored Verica to his throne first departed from Silchester and then rejoined the remainder of the Legion who may have rested at “Caesar’s Camp”, Bracknell.