The Duke of Marlborough’s second victory in the field over the

French army of Louis XIV: probably as great a success as Blenheim

Duke of Marlborough and his staff at the Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: piccture by Laguerre: Colonel Brinfield lies in the right foreground

The previous battle of the War of the Spanish Succession is the Battle of Blenheim

The next battle of the War of the Spanish Succession is the Battle of Oudenarde

To the War of the Spanish Succession index

War: Spanish Succession

Date of the Battle of Ramillies: 12th May 1706 (Old Style) (23rdMay 1706 New Style). The dates in this page are given in the Old Style.

Place of the Battle of Ramillies: Flanders.

Combatants at the Battle of Ramillies: British, Dutch, Austrians, Hanoverians, Prussians and Danes against the French and Bavarians. Scots, Irish, Swiss and Germans fought in the battle on both sides.

Generals at the Battle of Ramillies: The Duke of Marlborough against the French Marshal Villeroi.

John Churchill Duke of Marlborough: Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession

Size of the armies at the Battle of Ramillies: The Allied army comprised 62,000 troops (74 battalions, 123 squadrons and 120 guns and mortars) while the French army comprised 60,000 troops (70 battalions, 132 squadrons and 70 pieces of artillery).

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Ramillies:

The British Army of Queen Anne comprised troops of Horse Guards, regiments of horse, dragoons, Foot Guards and foot. In time of war the Department of Ordnance provided companies of artillery, the guns drawn by the horses of civilian contractors.

These types of formation were largely standard throughout Europe. In addition the Austrian Empire possessed numbers of irregular light troops; Hussars from Hungary and Bosniak and Pandour troops from the Balkans. During the 18th Century the use of irregulars spread to other armies until every European force employed hussar regiments and light infantry for scouting duties.

Duc de Villeroy: Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Alexandre-François Caminade

Horse and dragoons carried swords and short flintlock muskets. Dragoons had largely completed their transition from mounted infantry to cavalry and were formed into troops rather than companies as had been the practice in the past. However they still used drums rather than trumpets for field signals.

Infantry regiments fought in line, armed with flintlock musket and bayonet, orders indicated by the beat of drum. The field unit for infantry was the battalion comprising ten companies, each commanded by a captain, the senior company being of grenadiers. Drill was rudimentary and once battle began formations quickly broke up. The practice of marching in step was in the future.

The paramount military force of the period was the French army of Louis XIV, the Sun King. France was at the apex of her power, taxing to the utmost the disparate groupings of European countries that struggled to keep the Bourbons on the western bank of the Rhine and north of the Pyrenees.

Marlborough and his British regiments acted as an uncertain mortar in keeping the edifice of the Imperial cause in Flanders intact.

The War of the Spanish Succession was an early outing for the new British Army established after the Restoration in 1685. The regiments that took the field were the forebears of powerful Victorian institutions; Foot Guards, King’s Horse, Royal Dragoons, Royal Scots, Buffs, Royal Welch Fusiliers, Cameronians, Royal Scots Fusiliers and several other prestigious corps.

Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Jan van Huchtenburg

Britain fell behind its continental enemies and allies in many respects. There was no formal military education for officers of the Army, competence coming from experience on the field of battle. Commissions in the horse, dragoons and foot were acquired by purchase, permitting the wealthy to achieve often unmerited promotion.

Support services were not formally established and depended on the commander. A major contributing feature to the Duke of Marlborough’s success in the field was his concern that his soldiers be properly supplied and by his consummate ability to organise and administer that supply.

While every army had formal and explicit rank structures the realities of command and influence were still largely decided by social standing, particularly between armies of different nationality. It was a matter of necessity for John Churchill to have the status of Duke of Marlborough to enable him to exercise decisive influence over the fractious foreign officers he had to work with and over some of his own nationality. In reality his status as duke, while probably of greater significance than his military rank of Captain General, was insufficient to enable him to act as a true commander-in-chief rather than as quasi-chairman of a committee of Dutch, Austrian and British generals.

The uniform of the British Regiments was the long red coat turned back at the lapels and cuffs to show the facings of the regimental colour; dark blue for guards and royal regiments; yellow, green, white or buff for many of the others. The Royal Horse Guards wore blue uniforms; as did the artillery, an organization not yet incorporated into the army proper.

Headgear was the tricorne hat, except for the company of grenadiers in each battalion of foot, the Horse Grenadier Guards, the Royal North British Dragoons (Scots Greys), the three regiments of fusiliers (Royal, Royal North British and Royal Welch) and the drummers of dragoons and foot, all of whom wore the mitre cap.

For the infantry a cross belt carried the cartridge case hanging on the right hip. A second cross belt carried the bayonet and hanger sword. Ammunition, carried in the cartridge case, comprised cartridges of paper wrap containing the ball and gunpowder.

French Infantry: Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Jean Anthoine Watteau

For the other European armies national uniforms were in their infancy. The Danish infantry wore grey coats and breeches with green stockings. Some Danish cavalry regiments wore the old buff coats. Hanoverian regiments had taken to wearing red coats. The Prussian army wore dark blue. The Dutch army wore a motley of uniforms although the Guards wore blue and were referred to as the Blue Guards. The native French regiments wore white coats. The foreign regiments in French service, the Scots, Irish and Swiss wore red coats.

Winner of the Battle of Ramillies: Decisively the army of the Duke of Marlborough.

George Hamilton Earl of Orkney: Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession

British Regiments at the Battle of Ramillies:

King’s Regiment of Horse; later the King’s Dragoon Guards and now the 2nd Queen’s Dragoon Guards.

3rd Regiment of Horse; later the 3rd Dragoon Guards, then the 3rd Carabineers and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

5th Regiment of Horse; later the 5th Dragoon Guards, then the 5th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

6th Regiment of Horse; later the 6th Dragoon Guards, then the 3rd Carabineers and now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

7th Regiment of Horse; later the 7th Dragoon Guards, then the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

Royal North British Regiment of Dragoons; the Royal Scots Greys and now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

5th Dragoons; later the 5th Lancers, then the 16th/5th Royal Lancers and now the Royal Lancers.

1st Regiment of Foot Guards; now the Grenadier Guards.

The Royal Regiment; now the Royal Scots.

3rd Foot, the Buffs; now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment.

8th King’s Foot; now the King’s Regiment.

10th Foot; later the Lincolnshire Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

15th Foot; later the East Yorkshire Regiment and now the Prince of Wales’s Regiment of Yorkshire.

British 16th Foot charging at the Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Richard Simkin

16th Foot; later the Bedfordshire Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

18th Foot, Royal Irish Regiment; disbanded in 1922.

Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Royal Welch Fusiliers.

24th Foot; later the South Wales Borderers and now the Royal Regiment of Wales.

26th Foot, the Cameronians; later the Scottish Rifles, disbanded in 1968.

28th Foot; later the Gloucestershire Regiment and now the Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Regiment.

29th Foot; later the Worcestershire Regiment and now the Worcestershire and Sherwood Foresters Regiment.

37th Foot: later the Royal Hampshire Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment.

Royal Artillery.

Background to the Battle of Ramillies: Following the great victory of Blenheim on the Danube in 1704 and the collapse of King Louis XIV’s grand plan to overwhelm the Austrian Empire by taking Vienna, the focus of the war for Britain returned to Flanders and Brabant, modern Belgium.

In April 1706 the Duke of Marlborough returned to the Low Countries for the campaigning season to find the French army under Marshal Villeroi established behind the defensive line of the Dyle River and showing few signs of moving from this safe position. There seemed little prospect of a decisive field action that year.

Marlborough leaked stories to the French high command that he intended to attack the important fortress town of Namur. To his surprise Villeroi’s army began a forward move. While perhaps the Namur story influenced the French marshal, his move was more likely prompted by stinging letters from King Louis requiring some action in Flanders to restore French prestige, severely damaged by the Battle of Blenheim. Marlborough hurried his army forward the meet the French and Bavarians.

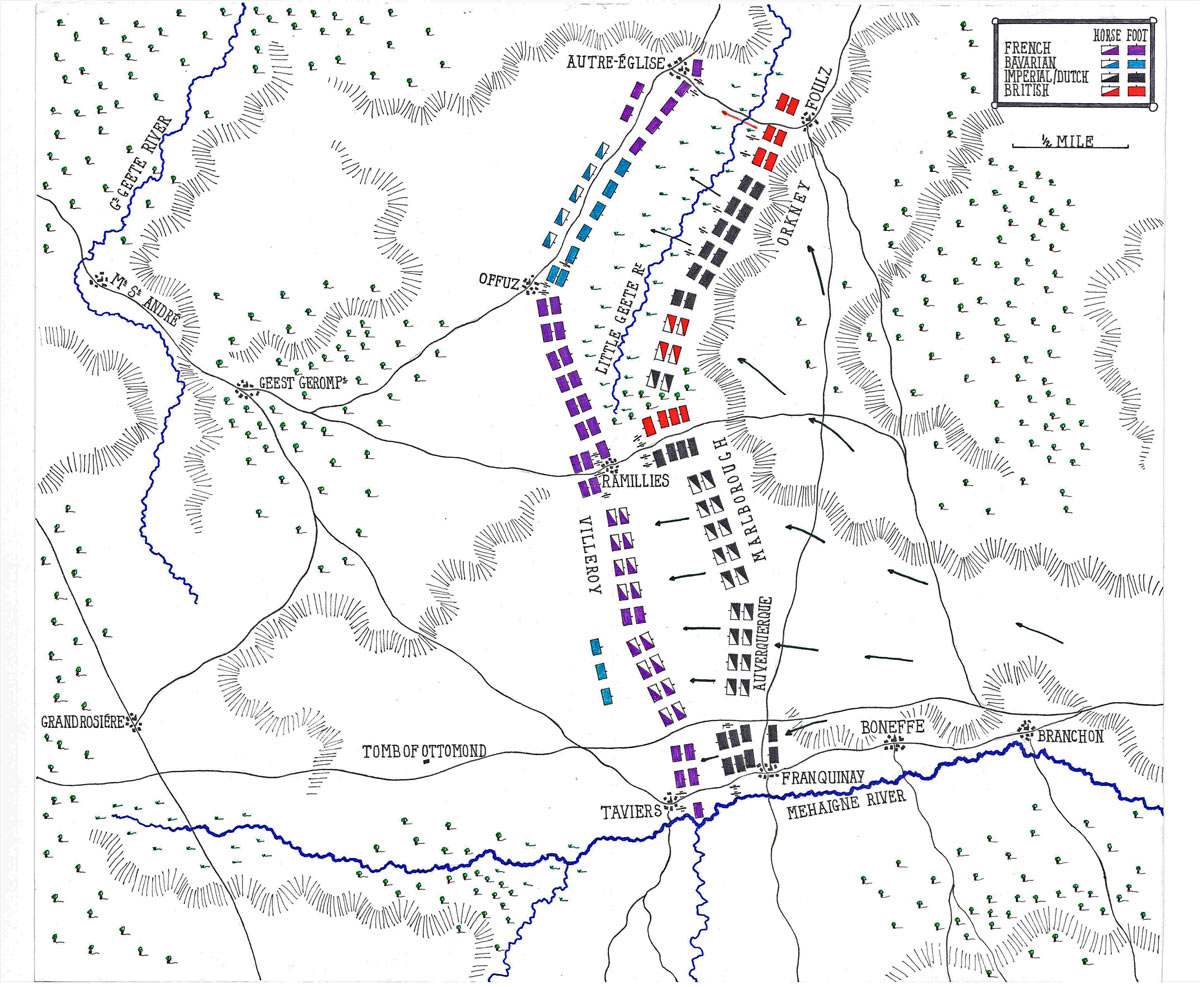

Map of the Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Ramillies:

On 11th May 1706 General Cadogan, Marlborough’s quartermaster general marched in advance of the main army to set up the next day’s camp at the village of Ramillies. As the morning mist dissolved Cadogan, observing the countryside from a point of vantage saw the French army encamped in the open ground before him. Marlborough soon came up with an advanced guard of cavalry and the opposing armies prepared for battle.

Villeroi’s army adopted an arc shaped position that ran from the River Mehaigne on its right flank up a slope to the village of Ramillies and from there in a continuing curve behind the marshy Little Gete River to the village of Autre Eglise on its extreme left. The French were busy fortifying the villages of Tavier on the River Mehaigne, Ramillies in the centre of their line, Offuz further to the left and Autre Eglise, garrisoning them with infantry and guns. The length of the French line was some four miles.

First Foot Guards at the Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Richard Simkin

As at Blenheim the pinning of the French to these fortified strongpoints would hamper the movement of troops along the line and enable Marlborough to choose the decisive point of attack. Villeroi compounded these difficulties by allowing his army’s substantial baggage train to remain too close to the French line further impeding movement.

Marlborough began the battle with an attack by British, Dutch and German regiments of foot commanded by Lord Orkney against the French left in the area of Autre Eglise. The marshy ground and the Little Gete made this a tricky operation and Marlborough soon ended the assault, ordering the regiments to return to the hilly ground to the East of the Little Gete, but not before Villeroi had drawn significant infantry forces from his centre to reinforce his left against the attack.

The Duke of Marlborough at the Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by R. Granville Baker

It is said that Marlborough intended this assault to be a feint. Once the British Foot regained the hills part of the force defiled off to the left to join the subsequent attack on Ramillies. These regiments were ordered to leave their colour parties on the right to confuse the French into thinking there remained a threat in that area.

On the left flank four Dutch battalions moved forward along the bank of the Mehaigne River to attack the villages of Franquinay and Taviers, while a substantially larger force of foot attacked Ramillies in the French centre, held by the Irish Regiments in the French service, Dorrington’s, Lee’s and Clare’s with seventeen further battalions.

While these infantry attacks got under way the veteran Dutch General Auverquerque moved into the ground between these villages with a strong force of cavalry.

Once the two villages on the bank of the Mehaigne were in allied hands and Ramillies masked by the infantry attack, Auverquerque launched his cavalry at the French horse to his front. There then followed a number of massed cavalry mêlées with the advantage swinging from one side to the other. Marlborough brought up mounted regiments from the right wing and plunged with them into the combat.

In the confused fighting the Duke was himself attacked by a party of French dragoons and unhorsed. He was rescued by his aide de camp, Captain Molesworth. During the incident Colonel Brinfield, Marlborough’s secretary was killed by a canon shot as he assisted the Duke to remount.

French soldiers after the battle: Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Jean Anthoine Watteau

A decisive thrust was now delivered by the Duke of Württemberg, leading a force of Danish Horse and Dutch Guards along the bank of the Mehaigne and around Villeroi’s right flank. During this attack Württemberg’s cavalry charged and overwhelmed the French Gens D’Armes. The French cavalry, having until this point held their own with great élan began to fall back.

In the centre the allied infantry assault on Ramillies after some hours of heavy fighting pushed the French Foot out of the village and supported by British cavalry moved on to assault Offuz.

French battalions and cavalry regiments attempting to move from the unengaged left to the centre to shore up the breaking line found themselves inextricably entwined with the mass of baggage carts.

With the retreat of the cavalry on the right and the expulsion of the French foot from Ramillies and then Offuz, Villeroi’s army retreated all along the line. Pressed hard by the British cavalry the French and Bavarian regiments began to disintegrate and the retreat became a rout.

Unlike Blenheim, on this occasion there was a powerful force of fresh cavalry to take up the pursuit and Villeroi’s army was harried over a distance of 20 miles, causing its complete collapse.

Pursuit of the French after the Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Laguerre

Casualties at the Battle of Ramillies: Allied casualties were 3,500. French casualties were 13,000. The whole of the French and Bavarian artillery, 70 guns and mortars, was captured.

Follow-up to the Battle of Ramillies:

Marlborough’s prompt exploitation of the victory enabled him to take Louvain and the line of the Dyle River from the French. In addition Brussels, Malines, Lerre and Alost surrendered to the allies, followed by Ghent, Bruges, Damme and finally Antwerp and Brussels. Within a fortnight of Ramillies Villeroi had lost almost the whole of Flanders and Brabant to Marlborough and fallen back to the French frontier.

Duke of Marlborough leads the British Cavalry into action at the Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Regimental anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Ramillies:

Lord Clarke’s Irish Regiment attacking at the Battle of Ramillies 12th May 1706 in the War of the Spanish Succession

- Ramillies was the only battle of the war at which the Duke of Marlborough was not in partnership with the Imperial commander Prince Eugene of Savoy. Prince Eugene was at the time commanding the Imperial army in Italy, defeating the French at the Battle of Turin.

- It is claimed that in the assault on Ramillies the Irish Brigade in the French service captured the colours of an English regiment, said to have been the Buffs. The colours were given into the safe keeping of the Irish Sisters of an abbey at Ypres.

- The Royal Scots Greys under Lord John Hay took part in the overthrow of the Gens D’Armes by Auverqueque’s cavalry.

- Lord Clare of the Irish Brigade was killed in the battle, as were the Prince de Soubise and Marshal Tallard’s son.

- The Duchess of Marlborough ensured that Colonel Brinfield’s widow received an annual pension of £100 following the death of her husband while assisting the Duke at the battle.

- The Dutch regiments, including several Scots regiments in the Dutch service distinguished themselves in the battle.

- Following the battle, the allied troops took to cocking their hats in the “tricorne” form, known as the “Ramillies cock of the hat”. In addition the soldiers took to plaiting their long hair into the “Ramillies tail”.

- One of the few British officers taken prisoner at Ramillies was Ensign Gardener. As colonel of a regiment of dragoons Gardner was killed at the Battle of Prestonpans in 1745 during the Jacobite Rebellion.

- See the British Battles blog on the tapestries commemorating the Duke of Marlborough’s victories during the War of the Spanish Succession at Blenheim Palace.

References for the Battle of Ramillies:

Marlborough as military commander by David Chandler

Fortescue’s History of the British Army Volume 1.

Grant’s British Battles.

Sullivan’s Irish Brigades in the Service of France.

The previous battle of the War of the Spanish Succession is the Battle of Blenheim

The next battle of the War of the Spanish Succession is the Battle of Oudenarde

To the War of the Spanish Succession index