The Duke of Marlborough’s fourth, bloodiest and least

conclusive defeat in the field of the French army of Louis XIV, fought on 11th September 1709

The previous battle of the War of the Spanish Succession is the Battle of Oudenarde

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Dettingen

To the War of the Spanish Succession index

War: Spanish Succession

Date of the Battle of Malplaquet: 11th September 1709

Place of the Battle of Malplaquet: In Northern France near the Belgian border.

John Churchill Duke of Marlborough: Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession

Combatants at the Battle of Malplaquet: British, Dutch, Austrians, Hanoverians, Prussians and Danes against the French and Bavarians. Scots, Irish, Swiss and Germans fought in the battle on both sides. It is said that every European nationality was represented in the battle.

Generals at the Battle of Malplaquet: The Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene of Savoy against Marshal Villars and Marshal Boufflers.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Malplaquet: The two armies were about the same size at around 100,000 men. The French are said to have deployed 130 battalions of foot, 260 squadrons of cavalry and 80 guns. The allies are credited with 129 battalions, 252 squadrons and 101 guns.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Malplaquet:

The British Army of Queen Anne comprised troops of Horse Guards, regiments of horse, dragoons, Foot Guards and foot. In time of war the Department of Ordnance provided companies of artillery, the guns drawn by the horses of civilian contractors.

These types of formation were largely standard throughout Europe. In addition the Austrian Empire possessed numbers of irregular light troops; Hussars from Hungary and Bosniak and Pandour troops from the Balkans. During the 18th Century the use of irregulars spread to other armies until every European force employed hussar regiments and light infantry for scouting duties.

Horse and dragoons carried swords and short flintlock muskets. Dragoons had largely completed their transition from mounted infantry to cavalry and were formed into troops rather than companies as had been the practice in the past. However they still used drums rather than trumpets for field signals.

Infantry regiments fought in line, armed with flintlock musket and bayonet, orders indicated by the beat of drum. The field unit for infantry was the battalion comprising ten companies, each commanded by a captain, the senior company being of grenadiers. Drill was rudimentary and once battle began formations quickly broke up. The practice of marching in step was in the future.

The paramount military force of the period was the French army of Louis XIV, the Sun King. France was at the apex of her power, taxing to the utmost the disparate groupings of European countries that struggled to keep the Bourbons on the western bank of the Rhine and north of the Pyrenees.

Marlborough and his British regiments acted as an uncertain mortar in keeping the edifice of the Imperial cause in Flanders intact.

The War of the Spanish Succession was an early outing for the new British Army established after the Restoration in 1685. The regiments that took the field were the forebears of powerful Victorian institutions; Foot Guards, King’s Horse, Royal Dragoons, Royal Scots, Buffs, Royal Welch Fusiliers, Cameronians, Royal Scots Fusiliers and several other prestigious corps.

Britain fell behind its continental enemies and allies in many respects. There was no formal military education for officers of the Army, competence coming from experience on the field of battle. Commissions in the horse, dragoons and foot were acquired by purchase, permitting the wealthy to achieve often unmerited promotion.

Support services were not formally established and depended on the commander. A major contributing feature to the Duke of Marlborough’s success in the field was his concern that his soldiers be properly supplied and by his consummate ability to organise and administer that supply.

While every army had formal and explicit rank structures the realities of command and influence were still largely decided by social standing, particularly between armies of different nationality. It was a matter of necessity for John Churchill to have the status of Duke of Marlborough to enable him to exercise decisive influence over the fractious foreign officers he had to work with and over some of his own nationality. In reality his status as duke, while probably of greater significance than his military rank of Captain General, was insufficient to enable him to act as a true commander-in-chief rather than as quasi-chairman of a committee of Dutch, Austrian and British generals.

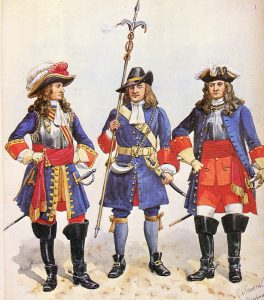

The uniform of the British Regiments was the long red coat turned back at the lapels and cuffs to show the facings of the regimental colour; dark blue for guards and royal regiments; yellow, green, white or buff for many of the others. The Royal Horse Guards wore blue uniforms; as did the artillery, an organization not yet incorporated into the army proper.

Headgear was the tricorne hat, except for the company of grenadiers in each battalion of foot, the Horse Grenadier Guards, the Royal North British Dragoons (Scots Greys), the three regiments of fusiliers (Royal, Royal North British and Royal Welch) and the drummers of dragoons and foot, all of whom wore the mitre cap.

French officer with regimental colour: Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession

For the infantry a cross belt carried the cartridge case hanging on the right hip. A second cross belt carried the bayonet and hanger sword. Ammunition, carried in the cartridge case, comprised cartridges of paper wrap containing the ball and gunpowder.

For the other European armies national uniforms were in their infancy. The Danish infantry wore grey coats and breeches with green stockings. Some Danish cavalry regiments wore the old buff coats. Hanoverian regiments had taken to wearing red coats. The Prussian army wore dark blue. The Dutch army wore a motley of uniforms although the Guards wore blue and were referred to as the Blue Guards. The native French regiments wore white coats. The foreign regiments in French service, the Scots, Irish and Swiss wore red coats.

Winner of the Battle of Malplaquet: the Duke of Marlborough and his allies although not conclusively.

British Regiments at the Battle of Malplaquet:

King’s Regiment of Horse; later the King’s Dragoon Guards and now the 2nd Queen’s Dragoon Guards.

3rd Regiment of Horse; later the 3rd Dragoon Guards, then the 3rd Carabineers and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

5th Regiment of Horse; later the 5th Dragoon Guards, then the 5th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

6th Regiment of Horse; later the 6th Dragoon Guards, then the 3rd Carabineers and now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

7th Regiment of Horse; later the 7th Dragoon Guards, then the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards and now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

Royal North British Regiment of Dragoons; the Royal Scots Greys and now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

5th Dragoons; later the 5th Lancers, then the 16th/5th Royal Lancers and now the Royal Lancers.

1st Regiment of Foot Guards; now the Grenadier Guards.

The Coldstream Regiment of Foot Guards.

The Royal Regiment; now the Royal Scots.

3rd Foot, the Buffs; now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment.

8th King’s Foot; now the King’s Regiment.

10th Foot; later the Lincolnshire Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

15th Foot; later the East Yorkshire Regiment and now the Prince of Wales’s Regiment of Yorkshire.

16th Foot; later the Bedfordshire Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

18th Foot, the Royal Irish; disbanded in 1922.

19th Foot; now the Green Howards.

Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Royal Welch Fusiliers.

24th Foot; later the South Wales Borderers and now the Royal Regiment of Wales.

26th Foot, the Cameronians; later the Scottish Rifles, disbanded in 1968.

28th Foot; later the Gloucestershire Regiment and now the Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Regiment.

29th Foot; later the Worcestershire Regiment and now the Worcestershire and Sherwood Foresters Regiment.

37th Foot: later the Royal Hampshire Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment.

Royal Artillery.

British artillery early 18th Century: Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Richard Simpkin

Background to the Battle of Malplaquet:

In the spring of 1709 King Louis XIV informally approached the Duke of Marlborough with a view to ending the war that was proving so disastrous for France. The terms Marlborough was instructed to put to Louis were unacceptable even with French fortunes at a low ebb and the war continued.

By the summer of 1709 the French commander-in-chief in Flanders, Marshal Villars, commanded a large army, reinforced with regiments taken from other theatres. Nevertheless Marlborough took the fortress city of Tournay and advanced on Mons.

Villars moved to protect Mons, taking up a position between the villages of La Folie and Malplaquet in an extensive gap in the forests that covered the area.

On 29th August 1709, the allied and Franco/Bavarian armies lay within striking distance of each other. Marlborough was for an immediate attack, but was held back by a consensus among the senior allied generals and the Dutch deputies, who wielded great influence that the army should await the further detachments that were hurrying to join it.

Villars army was actively fortifying its position and used the additional time to great effect. The arrival in camp of the old Marshal, the Duc de Boufflers, boosted the morale of the French troops.

On 30th August 1709 the Dutch deputies insisted on putting off the attack for another day, giving the French yet more time to build a formidable position.

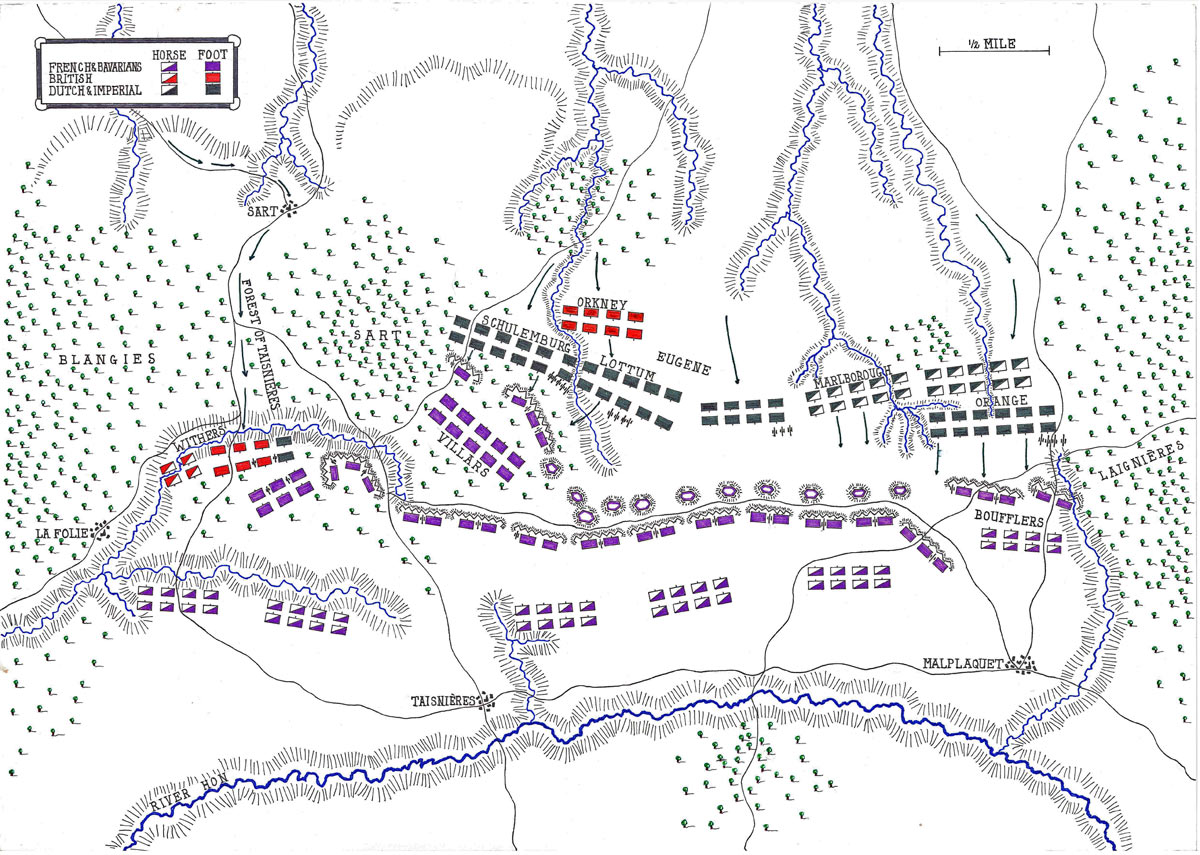

Map of the Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Successioni: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Malplaquet:

The French and Bavarian army lay with its right flank embedded in the Forest of Lagnières. Their lines, covered by log abattis fronted with redoubts, stretched for some three miles into the Forest of Taisnières. At the left end of the French line a fortification jutted forward from the main line onto a hill in the forest. It was here that the decisive fighting on the left wing would take place.

Villars massed his cavalry behind the French line.

Breaking through such a strongly fortified line gave the allied troops a daunting task, but the defender’s ability to manoeuvre and shift forces from one place to another was severely restricted and the French and Bavarian cavalry could take no part in the battle until the line was pierced and the allies broke through.

French Infantry on the march: Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Jean Anthoine Watteau

In the centre and on the left, woods gave the opportunity for allied troops to approach the French positions unseen.

Marlborough and Prince Eugene resolved to make use of the inflexibility of Villars’ position by making a feint attack on the French right and threatening the French centre, but delivering the true attack on the French left and enveloping the French left flank. It was decided to direct a force commanded by General Withers that was hastening up to reinforce the army to march straight around the French left flank and assault the village of La Folie.

Once the line had been pierced the Allied cavalry would sweep through and break up the French/Bavarian army.

First Foot Guards at the Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Richard Simkin

11th September 1709 dawned with a thick mist concealing the opposing armies from each other. The allies brought up batteries of heavy guns to bombard the flanks of the French army. The rest of the guns were distributed along the line.

Generals Lottum, Schulenburg and Lord Orkney commanded a substantial force of German and British foot for the assault on the French fortified left wing in the Forest of Taisnières. General Withers with five British battalions, fourteen foreign battalions and several regiments of cavalry moved around the French left flank towards the village of La Folie.

Thirty-one mainly Dutch battalions commanded by the Prince of Orange formed up for the feint towards the French right. The Prince was specifically commanded not to make a full assault unless ordered to.

The allied cavalry was distributed in support of these various forces.

King’s Carabiniers at the Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Richard Simkin

At 7.30am, the mist cleared and the battle began with an artillery bombardment. The two columns of foot moved forward towards each of the French flanks. The Prince of Orange halted and that of General Schulenburg marched on to begin the attack on the fortifications in the Forest of Taisnières.

It took much bitter fighting for the Allied foot to force the French infantry back from the first line of abattis: the regiments of Picardy and Champagne particularly distinguishing themselves in the French line, while the Buffs struggled through a marsh to deliver their attack.

At this point Villars called for reinforcements from the right flank commanded by the venerable Marshal Boufflers. But Boufflers was unable to comply as he was under heavy attack.

French Infantry bivouacking: Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Jean Anthoine Watteau

The Prince of Orange failed to comply with his orders. Instead of presenting a threat to the French right flank the Prince launched an all-out assault on the French positions in and around the Forest of Lagnières. The initial attack, led by the Prince, comprised Scottish regiments in the Dutch service, Tullibardine’s and Hepburn’s and the Dutch Blue Guards. Other regiments pressed forward, supported by Hanover battalions.

The assault was met with heavy artillery fire and a resolute defence directed by Marshal Boufflers. Determined though the Prince of Orange’s attack was, it was repelled with some 6,000 casualties.

The Prince of Orange’s attack was in breach of his specific orders and contrary to the allied plan, but it ensured that Marshal Boufflers was unable to release reinforcements to Villars’ left flank.

Schulenburg’s assault with his Prussian, Austrian and British foot was pressing the French hard, pushing them out of their fortifications in the forest, while Withers moved around the French flank, attacking the village of La Folie.

Villars called the Irish Brigade up from the French centre and launched it in reckless assault on the Prussian foot. After an initial success the Irish became dispersed in the woods and the allied advance resumed.

French Cavalry attacking at the Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession

During the desperate hand to hand fighting Prince Eugene was wounded in the head but continued in action. Marshal Villars received a severe leg wound and left the field, incapacitated. The French foot continued to resist but without guidance.

The allied battery moved forward and began a heavy bombardment of the main line of redoubts which was now assaulted by Lord Orkney’s British reserve. The Prince of Orange renewed his attack and took the abattis that faced the allied left.

French cavalry on the march at night: Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Jean Anthoine Watteau

Allied cavalry poured through the broken French line to be met by Marshal Boufflers leading the French Household cavalry, comprising the Mousquetaires, the Gens D’Armes and the Garde du Corps, and driven back. Orkney’s foot fought off the Gens D’Armes and Marlborough brought up the Prussian cavalry from the right flank. More French regiments joined the fray, but so did the Dutch horse, the struggle continuing until Boufflers was forced to draw off the French cavalry and retreat, joining the already withdrawing French foot.

The allied army had forced the French positions and won the battle, but at terrible cost and with the Franco/Bavarian army leaving the field in good order.

Casualties at the Battle of Malplaquet:

French and Bavarian casualties were 15,000. The allied casualties were 17,000. The French lost 16 cannon in the battle with many standards and colours.

Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Jan van Huchtenburg

Follow-up to the Battle of Malplaquet:

The fortress of Mons surrendered to the allied armies in the following month.

Marlborough was heavily criticised for the terrible casualties at Malplaquet. His enemies said he was more concerned with his own advancement than with the lives of his soldiers.

Malplaquet was the Duke of Marlborough’s last field battle. Following the siege and capture of Bouchain, another important French fortress, Marlborough was recalled to England finally brought down by the plotting of his enemies and the collapse of relations between Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough and Queen Anne.

Marlborough only returned to royal favour with the accession of the Elector of Hanover as King George I.

Prince James Francis Edward Stuart, the Old Pretender: Battle of Malplaquet 11th September 1709 War of the Spanish Succession: picture by Alexis Simon Belle

Regimental anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Malplaquet:

- The Chevalier de St George, the Old Pretender James Stuart, charged several times with the French Household Cavalry and was wounded in the battle.

- The French officer, the Comte D’Artagnan, was promoted Marshal for his gallantry in the battle.

- The Duke of Marlborough carries the informal title of “The Great Captain”. To his soldiers, of whose care he was constantly solicitous, he was known simply as “Corporal John.”

- Lord Orkney, having served under the Duke of Marlborough throughout the Spanish Succession War, later became Britain’s first field marshal.

- Of Marlborough’s veterans the last survivor, Henry Francis, is reputed to have lived to the age of 134 and died in New York in 1820. Ambrose Tennant died in Tetbury, Herefordshire in 1800 having served in the army for 60 years.

- See the British Battles blog on the tapestries commemorating the Duke of Marlborough’s victories during the War of the Spanish Succession at Blenheim Palace.

References for the Battle of Malplaquet:

- Marlborough as military commander by David Chandler

- Fortescue’s History of the British Army Volume 1.

- Grant’s British Battles.

- Sullivan’s Irish Brigades in the Service of France.

The previous battle of the War of the Spanish Succession is the Battle of Oudenarde

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Dettingen

To the War of the Spanish Succession index