The unsuccessful attempt by the Americans and the French to re-take Savannah, Georgia, on 9th October 1779

Attack of 2nd South Carolina Continentals on the Spring Hill Redoubt at the Siege of Savannah on 9th October 1779 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by A.I. Keller

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Monmouth

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Siege of Charleston

To the American Revolutionary War index

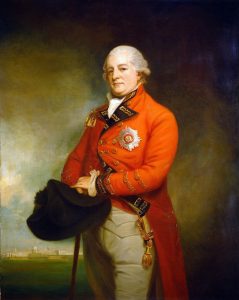

Major General Augustin Prévost, British commander at the Siege of Savannah September and October 1779 in the American Revolutionary War

Battle: Siege of Savannah

War: American Revolution

Date of the Siege of Savannah: September and October 1779

Place of the Siege of Savannah: City of Savannah, Georgia, in the United States of America.

Combatants at the Siege of Savannah: British regulars and loyalist volunteers against the American Continental Army and militia regiments and a large contingent of French troops.

Commanders at the Siege of Savannah: Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell commanded the British force that took Savannah. Major General Augustin Prévost arrived to command the British force holding the town during the Siege of Savannah.

Major General Benjamin Lincoln commanded the American Southern Army and the Count D’Estaing commanded the French fleet and troops at the Siege of Savannah.

Comte D’Estaing, French commander at the Siege of Savannah, September and October 1779 in the American Revolutionary War

Size of the armies at the Siege of Savannah: Major General Prévost’s British, Hessian and Loyalist American force comprised 3,200 men. Loyalist Americans predominated.

The combined American and French army commanded by Lincoln and D’Estaing comprised 600 American Continentals, 750 American militia and 3,500 French regular troops.

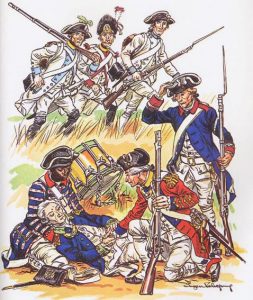

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Siege of Savannah:

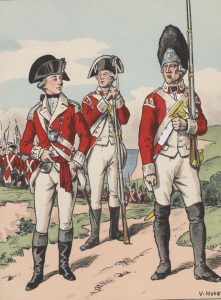

The British wore red coats, with bearskin caps for the grenadiers, tricorne hats for the battalion companies and caps for the light infantry.

The French troops wore white coats, with bearskin caps for the grenadiers and tricorne hats for the battalion companies.

The Americans dressed as best they could. Increasingly as the war progressed infantry regiments of the Continental Army mostly took to wearing blue or brown uniform coats. The American militia continued in rough clothing.

Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell, British commander at the capture of Savannah on 28th December 1778 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by George Romney

Both sides were armed with muskets. The British and French infantry carried bayonets. The American Continental infantry were supplied with bayonets, while the American militia were not. Many of the American troops on both sides carried rifled muskets. Both sides were supported by artillery.

Winner of the Siege of Savannah: The French and American attempt to capture Savannah from the British failed completely, and led directly to the British capture of Charleston, and a temporary loss of confidence in the French as reliable allies to the Americans.

British Regiments at the Siege of Savannah:

British Army and Loyalist Regiments: 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 71st Highlanders, battalion of light infantry, marines, three companies of grenadiers of the 60th Regiment, Hessian Regiment of von Trumbach, Hessian Regiment of Wissenbach, 1st and 2nd Battalions of De Lancey’s New York Volunteers, Isaac Allen’s New Jersey Volunteers, British Legion, King’s Rangers, Georgia Loyalist Militia, North Carolina Loyalist Volunteers, South Carolina Loyalist Volunteers, a troop of Loyalist light dragoons.

Major General Benjamin Lincoln, American commander at the Siege of Savannah, September and October 1779 in the American Revolutionary War

American Regiments at the Siege of Savannah:

1st, 2nd and 5th South Carolina Continentals, 1st Battalion of the Charleston militia, Georgia militia, Pulaski’s legion (around 200 mounted men).

British Capture of Savannah:

On 18th June 1778, General Sir Henry Clinton marched his British army out of Philadelphia on its route north to New York. Clinton’s instructions from Lord Germaine in London were to discontinue British offensive operations in the northern colonies, and to send a force of 3,000 men to attack the Americans in Georgia and South Carolina.

Major General Augustine Prévost, the British commander in Florida, was instructed to join the attack on the Americans in Georgia, with such troops as could be spared from Florida, and take command of the whole force.

De Lancey’s Brigade: Siege of Savannah, September and October 1779 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Charles M. Lefferts

The troops sent by Clinton, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell of Maclean’s Regiment, set sail from Sandy Hook, New York, on 27th November 1778, escorted by a Royal Navy squadron commanded by Commodore Sir Hyde Parker.

Campbell’s force arrived off Tybee Island, in the mouth of the Savannah River, on 23rd December 1778. Campbell put ashore a party of Highland troops, who brought back two captured local civilians. These two men revealed much information about the size of the garrison in Savannah and the positions of American troops.

Major General Robert Howe, American commander at the capture of Savannah on 28th December 1778 in the American Revolutionary War

Prévost had not arrived, but, in the light of the information he had obtained from the two locals, Campbell considered he had sufficient men to capture Savannah without waiting for him.

Major General Robert Howe, commanding the American southern army, marched, with a force of 700 Continental troops, 150 militia and several guns, from Sunbury, thirty miles down the coast to the south-west, to intercept Campbell.

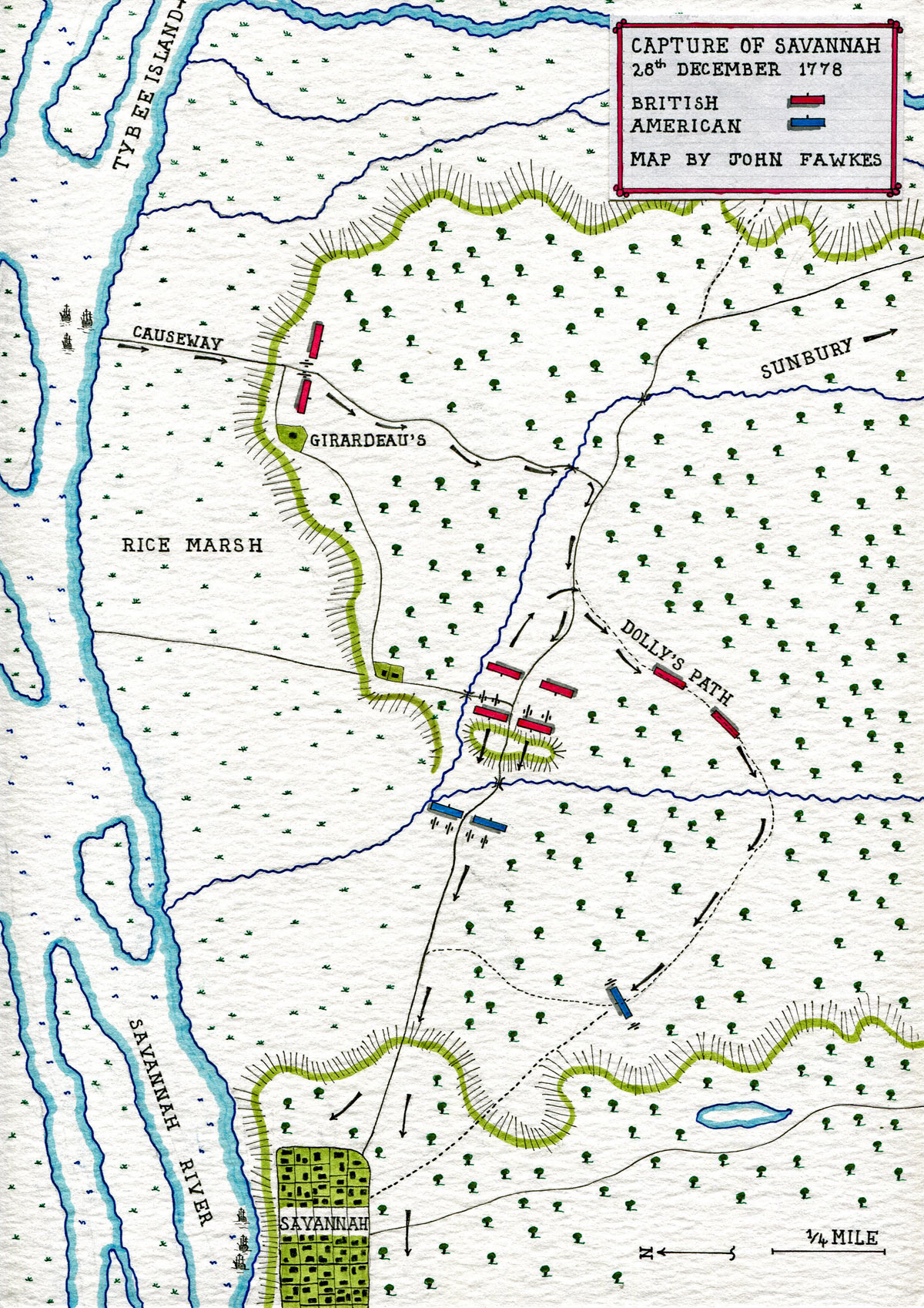

On 28th December 1778, the British squadron sailed up the Savannah River to the first point where hard landing was available, an area called Girardeau Plantation.

Girardeau House was situated on a hill, three quarters of a mile from the river, and was held by a party of American soldiers. Rice swamps lay between the house and the river bank, with a narrow wooden causeway from the jetty in the river, across the field to the house.

Captain Cameron led a party of Highlanders up the causeway, in the face of a heavy fire, and took Girardeau House, although Cameron and seven of the Highlanders were killed or wounded.

With Girardeau House and its landing point taken, Campbell was able to disembark the rest of his 3,000 troops.

Coming up from Sunbury, General Howe positioned his American force on the road to Savannah, with a swamp, beyond which was the Savannah River, on his left and swamp on his right, at a point where the road crossed a marshy rivulet. The Americans dug a trench and destroyed the bridge that carried the road over the rivulet.

Map of the capture of Savannah on 28th December 1778 in the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

Campbell left a battalion of the 71st Highlanders and DeLancey’s New York Provisionals to guard the landing point at Girardeau’s, and advanced up the road towards Howe’s position.

The British force halted 100 yards from the American line and Campbell came to the front to consider his next action. At this point an Afro-American called Quamino Dolly approached him, and told him there was a path leading through the swamp, to a point behind the American position. Campbell decided to make use of Dolly’s information, and circle around behind the Americans.

Campbell moved forward to a point where a rise concealed his men. The light infantry advanced towards the American left, and then doubled back.

Major Sir James Wright, Royal Governor of Georgia: capture of Savannah on 28th December 1778 during the American Revolutionary War

Major Sir James Baird led his light infantry, followed by Turnbull’s New York Volunteers, along Dolly’s path through the swamp, came out on the road behind the American position and attacked the Americans in the rear.

As soon as he heard the firing, Campbell advanced on the American front, with the rest of his force.

Howe’s position immediately collapsed. The militia fled to Savannah and, continuing through the town, attempted to swim the river on its border, many of them drowning.

The Continental troops were in better order, and withdrew by a path designated by Howe before the battle, skirting Savannah to the south and making for the South Carolina border.

Campbell was enabled to advance straight into Savannah, where he captured several guns and a considerable quantity of supplies and ammunition.

Irish Regiments in the French army, Dillon and Walsh: Siege of Savannah, September and October 1779 during the American Revolutionary War

Commodore Hyde Parker brought his ships up the Savannah River into Savannah Harbour, where he captured several American ships.

Note: This account is taken substantially from Ward’s ‘The War of the Revolution’. A contemporary British map of the battle shows that an American force was posted at the end of Dolly’s path, with several guns. Presumably this force was swept aside by Bailey’s light infantry, before they began their attack on the main American force positioned on the road behind the stream.

Over the following weeks, the Americans retreated out of Georgia entirely, and a new administration was set up to run the colony on behalf of the British Crown. Many of the Georgians hurried to express their support for King George III.

In September 1778, the American Congress had appointed Major General Benjamin Lincoln of Massachusetts to command the American forces in the Southern Department.

Lincoln was in Purysburg, on the north bank of the Savannah River, some twenty miles north of Savannah, where he was joined by the remnants of Howe’s force.

In April and May 1779, Major General Prévost made an unsuccessful foray into South Carolina in an attempt to take Charleston. By the end of June 1779, Prévost and his army were back in Georgia, the attempt on Charleston a failure, leaving a British force under Colonel Maitland holding Port Royal Island off the South Carolina coast.

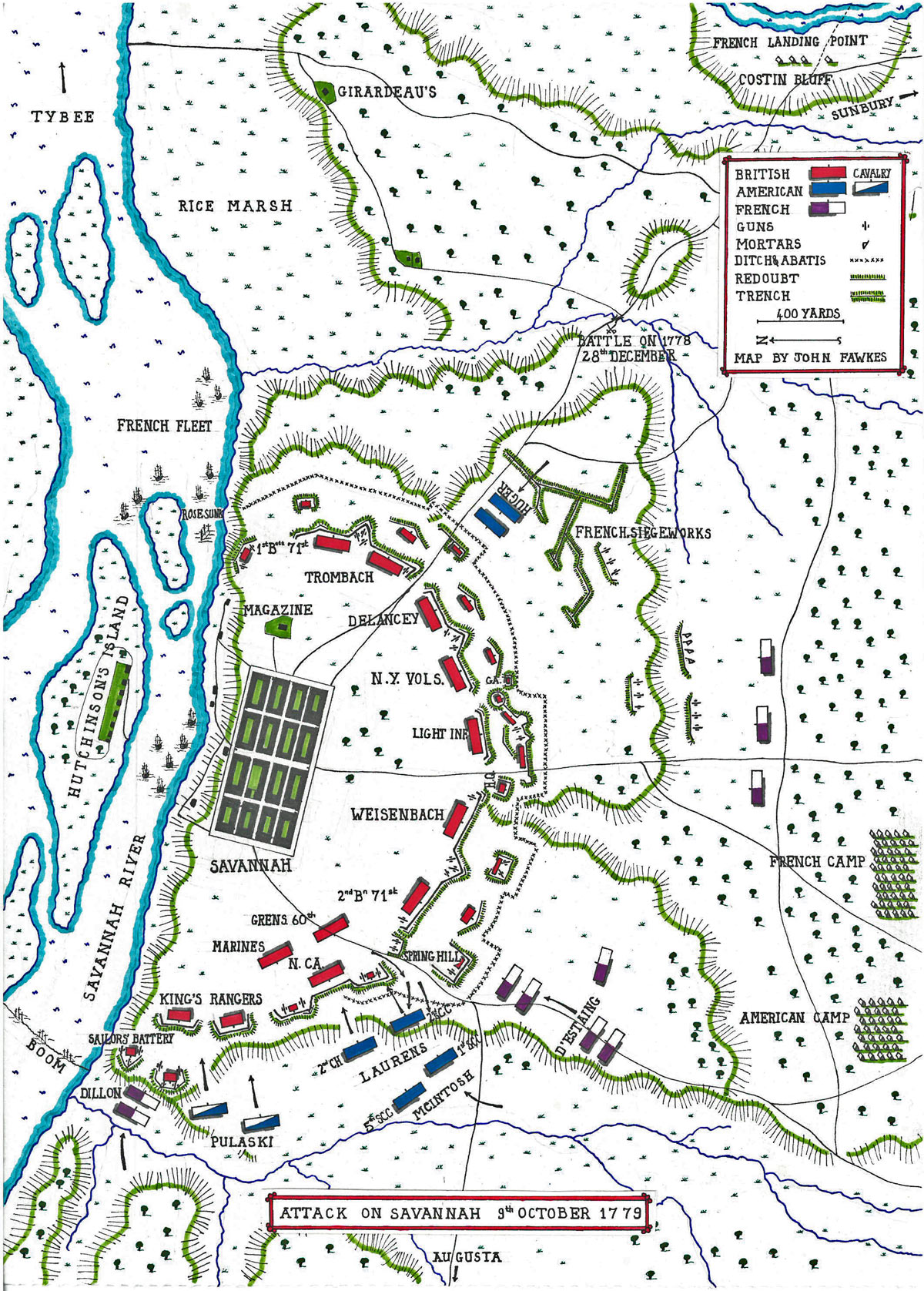

Map of the Siege of Savannah and the Attack on 9th October 1779 in the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Siege of Savannah:

Determined to recover Georgia, the American governor of South Carolina, Governor Routledge and General Moultrie, commanding the American forces in Charleston, wrote to the French naval commander in the West Indies, the Comte D’Estaing, requesting him to assist in an American attack on the British at Port Royal Island and in Savannah.

D’Estaing accepted the invitation and sailed for the southern American colonies, preceded by two ships of the line and three frigates. D’Estaing’s fleet comprised twenty ships of the line, two 50 gun ships, eleven frigates and transports carrying 6,000 troops.

On his way from the West Indies, D’Estaing captured a British naval squadron comprising HMS Experiment (50 guns), HMS Ariel and two transports carrying the pay for the British troops in Savannah and stores.

On 8th September 1778, D’Estaing’s fleet, with some American ships, arrived in the mouth of the Savannah River. Warned of the French approach, the British made their preparations; a fast brig despatched to New York with news of the threat, a summons to the troops on Port Royal Island and an outlying garrison in Sunbury to return to Savannah, and the naval squadron (HMS Vigilant, Fowey, Rose, Keppel and Germain) withdrawn up the river.

Savannah was a grid-patterned town, positioned on a bluff overlooking the south bank of the Savannah River.

Major General Prévost hurriedly began the construction of defensive works around the town, with the assistance of a force of several hundred slaves drafted in from the surrounding plantations.

The main feature of the defences was a ditch and wooden abatis or fence, built from the river on one side of the city around to the other, and backed by a rampart. Redoubts, built of logs infilled with sand, were positioned at strategic points behind the rampart.

British ships HMS Phoenix and Rose with galleys: Siege of Savannah, September and October 1779 during the American Revolutionary War

Several of the British ships were sunk across the river upstream of the town, and linked by a log boom, to form a barrier. HMS Rose was sunk in the narrow channel downstream. These measures prevented American vessels approaching Savannah from the north and French ships approaching from the estuary.

On 12th September 1779, D’Estaing brought 3,500 of his troops upstream by boat to a point five miles from Savannah, where they landed. D’Estaing was there joined by Pulaski’s Legion.

On 16th September 1779, D’Estaing summoned the garrison of Savannah to surrender to the King of France.

French Regiments at the Siege of Savannah; Armagnac, Hainault, Champagne, du Cap, Walsh and Guadeloupe: September and October 1779 during the American Revolutionary War

Major General Prévost prevaricated for 24 hours, to give Maitland time to bring his troops in from Port Royal Island.

Maitland was in the course of a hazardous and difficult march through the swamp from Port Royal Island, having to avoid the French ships at sea and Lincoln’s American army inland.

Once Maitland reached Savannah with his 800 British regular troops, Major General Prévost turned down the French demand that he surrender the town.

The British spent the period of the truce strengthening the town’s defences.

Lincoln’s American force reached Savannah on 16th September 1779 and joined D’Estaing. The combined American French army comprised 600 American Continentals, 750 American militia and 3,500 French troops. Major General Prévost’s force comprised 3,200 men.

The delay between the arrival of the French troops and the launching of the attack on Savannah was fatal to its success. On 8th September 1779, the fortifications were scanty, with only twenty-three guns in place around the defences. In the following days, working frantically, the British, the loyalist troops and the workforce of plantation slaves completed the defences, mounting on them the guns taken from the scuttled frigates. Once the work was finished, more than a hundred guns were in place to fend off the attackers.

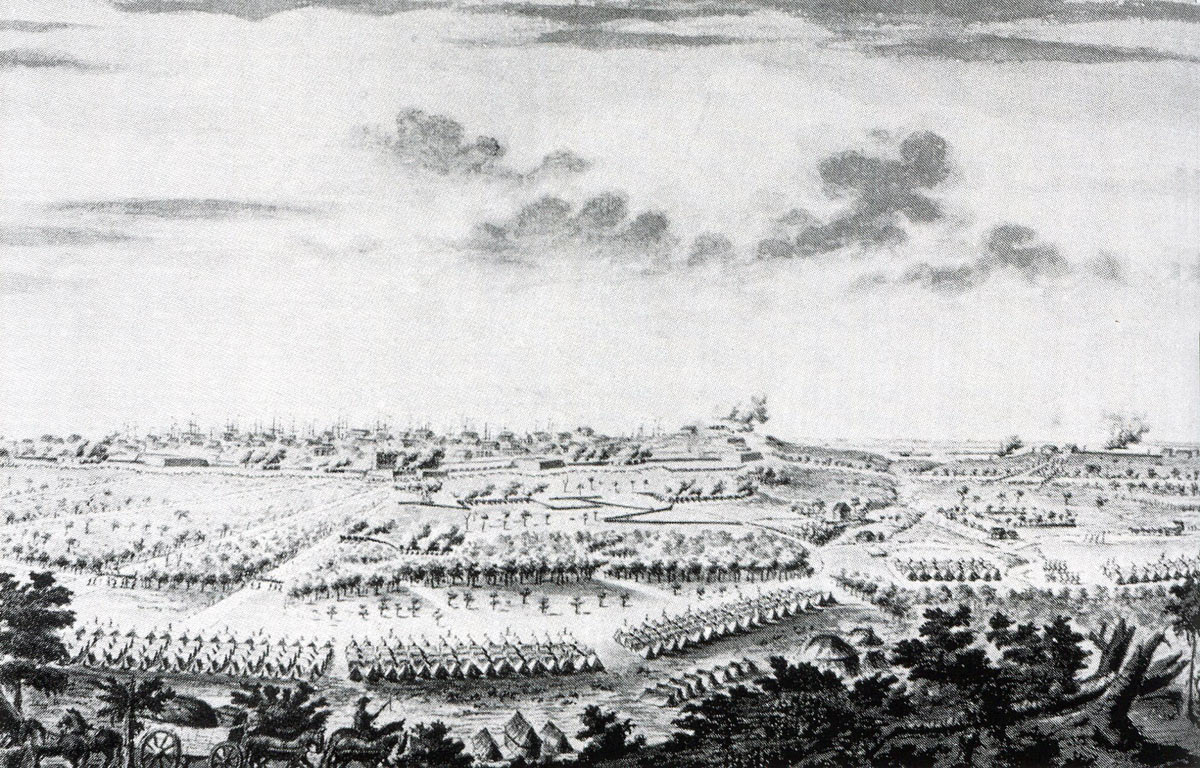

D’Estaing and Lincoln decided to subject Savannah to a formal siege. The French and American troops established separate camps, about a mile to the south of the fortifications, and the French siege train was brought up from the ships.

View of the siege works against the town at the Siege of Savannah September and October 1779 in the American Revolutionary War: contemporary picture by a French officer

Ground was broken, and the French and Americans began digging parallels towards the town’s fortifications, from a position on the southern plateau.

By 3rd October 1779, the French siege artillery was in place, and the next day, a bombardment of the town was opened from nine heavy mortars and thirty-seven large guns, in batteries to the south of Savannah, together with the guns from the French fleet in the river.

Major General Prévost made application to the French and Americans to be given the opportunity to remove the women and children to ships in the river. This was refused.

The bombardment was maintained for five days, and the town was badly damaged, but there was little impact on the fortifications.

American and French troops attacking Spring Hill Redoubt: Battle of Savannah on 9th October 1779 in the American Revolutionary War

The French siege engineers reported to D’Estaing, that it would take ten days to bring the trenches to within storming distance of the fortifications. D’Estaing was not prepared to wait that long. He feared for the safety of his fleet off the Savannah River, both from the weather and the British West Indies Fleet of Admiral Byron, which was reported to be approaching.

D’Estaing’s refusal to wait for the completion of the parallels led to the decision to storm the defences at 4am on 9th October 1779.

For the attack, the French troops were formed into three columns, two to attack and one in reserve, commanded by General Count Dillon, Baron de Steding and Colonel Vicomte de Noailles.

The Americans were to form two columns: Colonel John Laurens, leading 2nd South Carolina Continentals and 1st Charleston Militia, the second led by General McIntosh, comprising 1st and 5th South Carolina Continentals and the Georgia Militia.

Dillon’s French column was to infiltrate between the Sailor’s Battery and the Savannah River, at the northern point of the town’s defences.

General Huger was to carry out a feint attack at the other end of the British line.

The main attack of American and French troops was to be led by D’Estaing and Lincoln against the Spring Hill Redoubt.

British Marines: Siege of Savannah, September and October 1779 during the American Revolutionary War

The French and American plan was dogged with misfortune from its conception. Sergeant Major James Curry, of the Charleston Grenadiers, overheard senior American officers discussing the assault. Curry deserted to the British and informed them of the main points for the attack and its timings. The grenadiers of the 60th Regiment and a battalion of the 71st Highlanders, with a company of marines, all commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Maitland, were added to the garrison of the Spring Hill Redoubt.

On 9th October 1779, the day of the French and American attack on Savannah, the assembly and approach march of the attacking columns were delayed by fog, and dawn broke before the troops were under way.

Dillon’s column became lost, and emerged in front of the fortifications in the open, instead of infiltrating around them by a covered way along the river, as intended. The defenders opened a heavy canon fire on the French column and Count Dillon abandoned his attack, his men returning to camp.

On the extreme right, Huger also led his men out into the open and, after being subjected to a heavy bombardment, also returned to camp.

The American attack on the Spring Hill Redoubt was launched with courage and determination. Lauren’s American troops climbed the face of the bluff, crossed the ditch, cut through the abatis, and attacked the redoubt, all the while subjected to a heavy musketry and canon fire from the redoubt itself and from flanking batteries.

2nd South Carolina Continental Regiment: Siege of Savannah, September and October 1779 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Charles M. Lefferts

The first American regiment to assault the redoubt was the 2nd South Carolina Continentals, commanded by Colonel Marion. They attempted to scale the ramparts of the redoubt, but were repelled by the defenders’ heavy fire.

Several officers and soldiers tried to establish their colours on the ramparts, but were shot down. The last of these was Sergeant William Jasper of Fort Sullivan fame, who was mortally wounded.

Sergeant Jasper on the parapet of the Spring Hill Redoubt during the attack on Savannah on 9th October 1779 during the American Revolutionary War

Finally, Lauren’s column fell back behind the ditch, meeting McIntosh’s column as it came up in their support.

At this point, the grenadiers of the British 60th Regiment and the marines sallied out of the redoubt and attacked the confused mass of American soldiers, inflicting heavy casualties and driving them back to their camp.

173 Americans were killed in the attack on the Spring Hill Redoubt.

Further around the British line to the north, Pulaski led his 200 horsemen in an attempt to force a way through the fortifications. The cavalry reached the abatis and were subjected to a heavy musketry and canon fire. An early casualty was Pulaski himself, mortally injured by a discharge of canister. His men abandoned the attack and carried their dying leader back to camp.

Fatal wounding of Casimir Pulaski during the attack on Savannah on 9th October 1779 during the American Revolutionary War

All around the Savannah fortifications, the French and American assault failed.

Casualties at the Siege of Savannah:

The French and Americans lost 16 officers and 228 soldiers killed, and 63 officers and 521 soldiers wounded, in the attack on 9th October 1779. It is reported that half of Lauren’s attacking column became casualties.

It is said that the Comte D’Estaing was wounded in the attack.

The British, Hessians and loyalist Americans suffered casualties of 40 killed, 63 wounded and 52 missing.

Follow-up to the Siege of Savannah: D’Estaing did not choose to stay after the failure of the assault on Savannah. The French army returned to its ships and left.

General Lincoln marched the surviving remnant of his army back to Charleston.

American confidence in the French fell to a low ebb because of D’Estaing’s precipitous withdrawal and the failed assault on 9th October 1779.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Siege of Savannah:

- Ward makes the point that the predominance of American troops in Prévost’s British force shows the ‘Civil War’ nature of the fighting in the southern colonies during the Revolutionary War.

- The officers of the 2nd South Carolina Continentals attempting to place their colours on the rampart of the Spring Hill Redoubt were Lieutenants John Bush and Holmes. On becoming casualties, they were replaced by Lieutenant Henry Grey and Sergeant William Jasper. 2nd South Carolina Continentals was the regiment that provided the garrison for Fort Sullivan in the British attack on Charleston of the previous year. Lieutenant Henry Grey painted the two water colours of the British ships in action against Fort Sullivan and Sergeant Jasper retrieved the South Carolina flag and tied it to a gun sponge pole.

- Casimir Pulaski: Polish by nationality, Pulaski was one of the band of Europeans who arrived in America during the Revolutionary War, with claims of military experience and elevated social status. Pulaski fought in the revolts against Russian rule over Poland in the 1760s. His combative and arrogant personality forced him to leave Poland and seek employment, unsuccessfully, in the armies of Prussia and France. Pulaski arrived in Massachusetts in July 1777, with a recommendation from Benjamin Franklin, one of the stream of Europeans with which the American representatives in Paris plagued the Congress. Pulaski was mortally wounded during the cavalry attack on the British fortifications around Savannah on 9th October 1779. If he had not been struck down in this way, it seems unlikely that he would hold the important symbolic position in American tradition that he does (several counties in American states are named for him). The various military units Pulaski established and led do not appear to have contributed greatly to the American war effort, while his self-centred demands led to many difficulties. There is a tradition that Pulaski warned Washington of the British outflanking movement at the Battle of Brandywine. As the whole American right wing at Brandywine was falling back before Howe’s advance, it is hard to see how this tradition can be justified. US public holidays in memory of Pulaski are: General Pulaski Memorial Day (New York City on 11th October), Casimir Pulaski Day (Illinois and other states on 1st Monday of March).

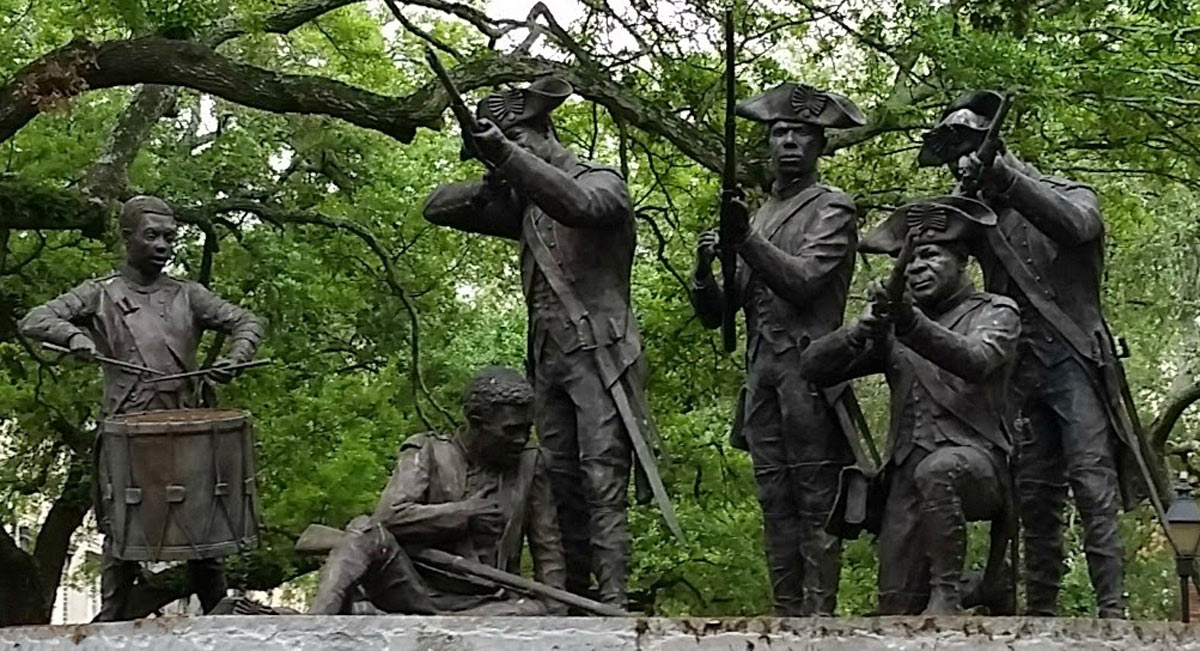

- One of the French regiments that fought in the attack on Savannah on 9th October 1779 was Les Chasseurs-Volontaires de Saint-Domingue, a corps raised by the French from slaves and liberated slaves in Saint-Domingue (later Haiti), with French senior officers. The part played by Les Chasseurs-Volontaires de Saint-Domingue in the attack on the British in Savannah is commemorated by a large and striking memorial in Savannah.

The battle is a prominent episode in the national traditions of Haiti. The leader of the Haitians in their subsequent war of independence from the French, Henri Christoph, is said to have been a drummer in Les Chasseurs-Volontaires de Saint-Domingue. After independence from the French, Henri Christoph became King Henri I of Haiti.

- Black slaves formed a significant corps of troops in the British force holding Savannah. It is reported that, with the end of any need for their services in the war, the British transported these men to the West Indies and sold them as slaves to the plantation owners.

- Charles Dickens’ character, Joe Willet in Barnaby Rudge, lost an arm fighting in the British army at the Siege of Savannah in 1779.

References for the Siege of Savannah:

History of the British Army by Sir John Fortescue

The War of the Revolution by Christopher Ward

The American Revolution by Brendan Morrissey

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Monmouth

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Siege of Charleston

To the American Revolutionary War index