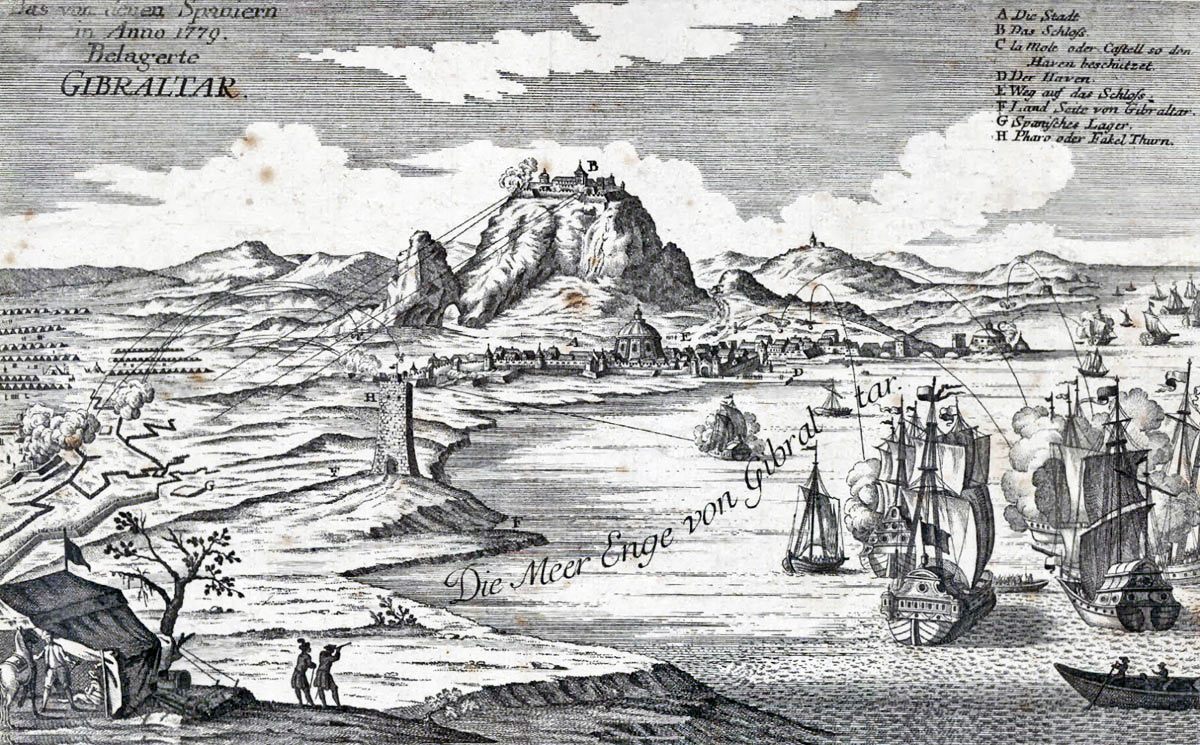

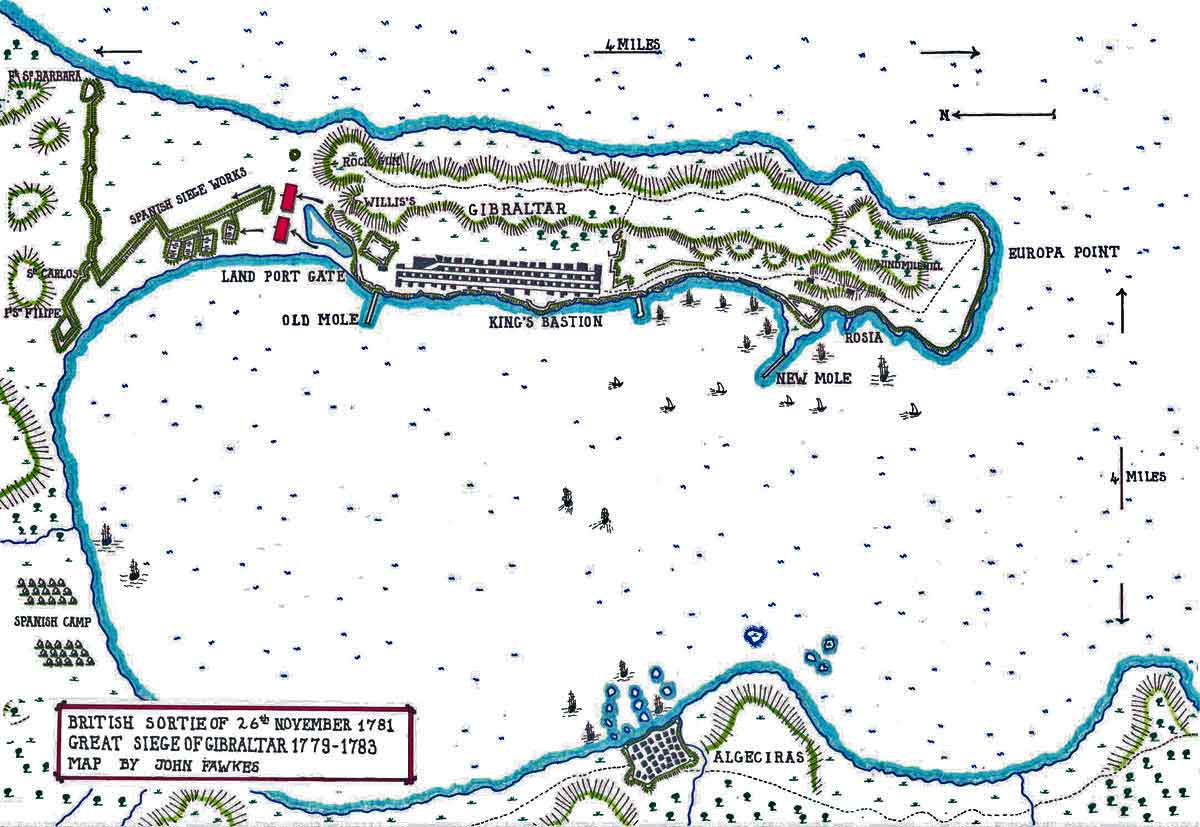

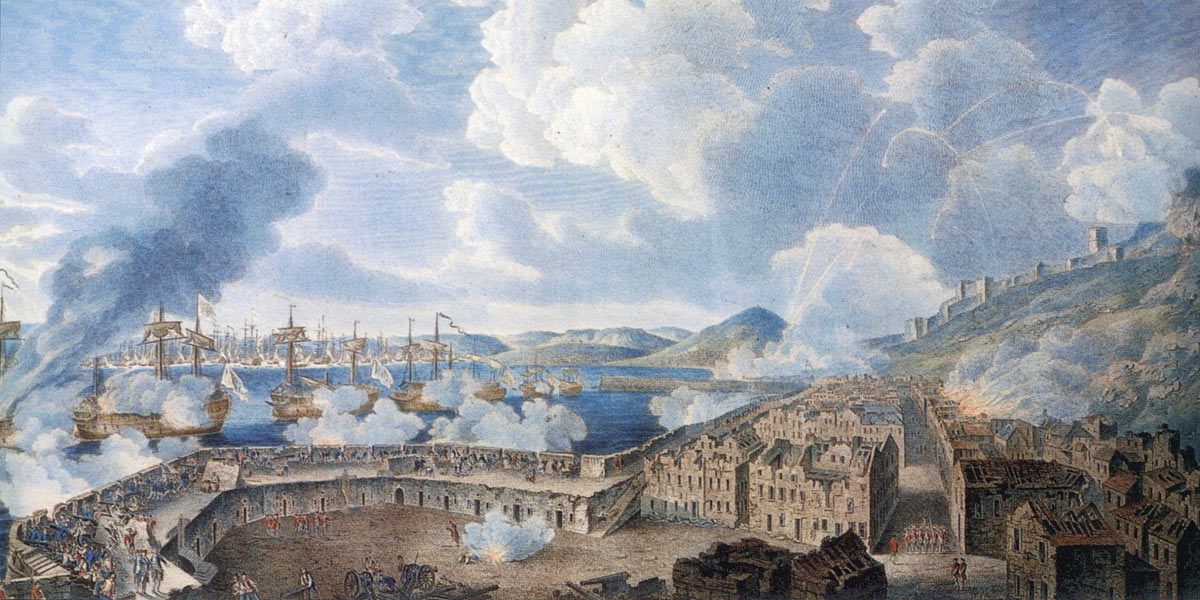

The siege of Gibraltar, between 8th July 1779 and 2nd February 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War

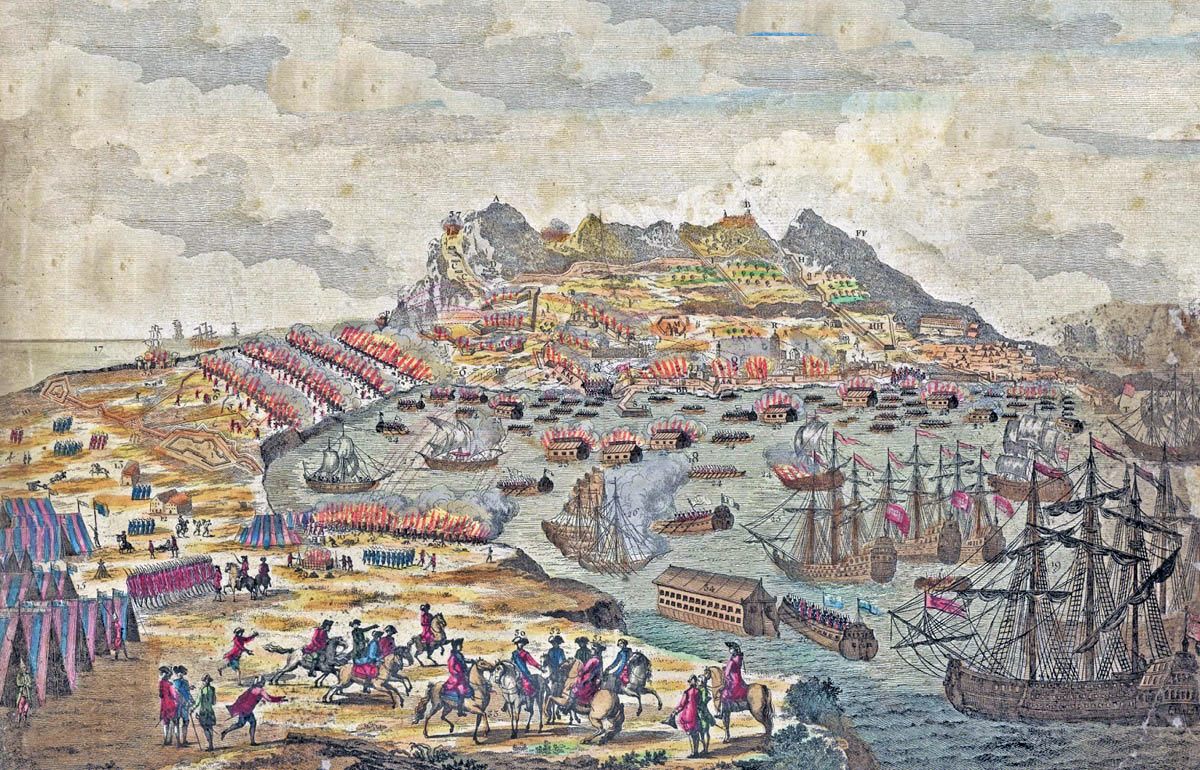

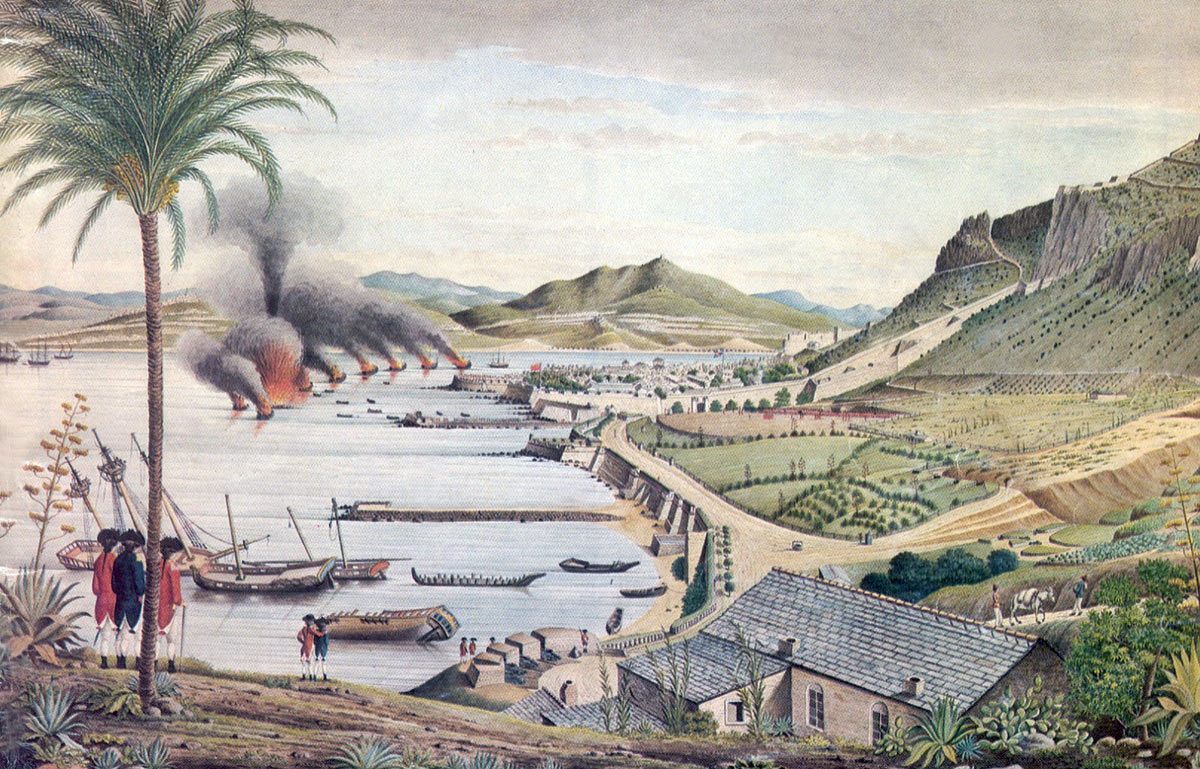

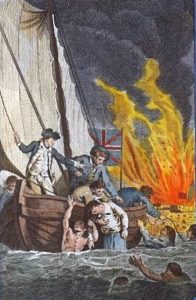

General Eliott watches the destruction of the Spanish Battering Ships on 13th September 1782 during the Siege of Gibraltar, 1779 to 1783 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by John Singleton Copley

12. Podcast of The Great Siege of Gibraltar, between 8th July 1779 and 2nd February 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

12. Podcast of The Great Siege of Gibraltar, between 8th July 1779 and 2nd February 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Yorktown

The next battle in the British Battles index is the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780

To the American Revolutionary War index

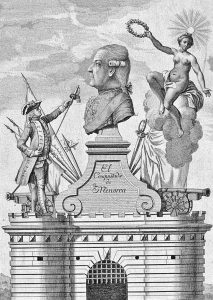

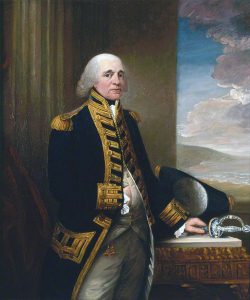

Lieutenant General George Augustus Eliott, governor of Gibraltar during the Great Siege 1779 to 1783: picture by Joshua Reynolds showing Eliott holding the keys to Gibraltar against a background of ‘the Great Siege’

Battle: Siege of Gibraltar

War: American Revolution

Date of the Siege of Gibraltar: 1779 to 1783

Place of the Siege of Gibraltar: Isthmus of Gibraltar off the coast of Southern Spain.

Combatants at the Siege of Gibraltar: The British garrison of Gibraltar comprised British regular troops, including a battalion of Scottish Highlanders, Hanoverian battalions and a detachment of Corsicans, with several ships of the British Royal Navy.

The siege was conducted by the Spanish army and navy with the assistance of the French army and navy.

Commanders at the Siege of Gibraltar: Lieutenant General George Augustus Eliott was the British governor of Gibraltar.

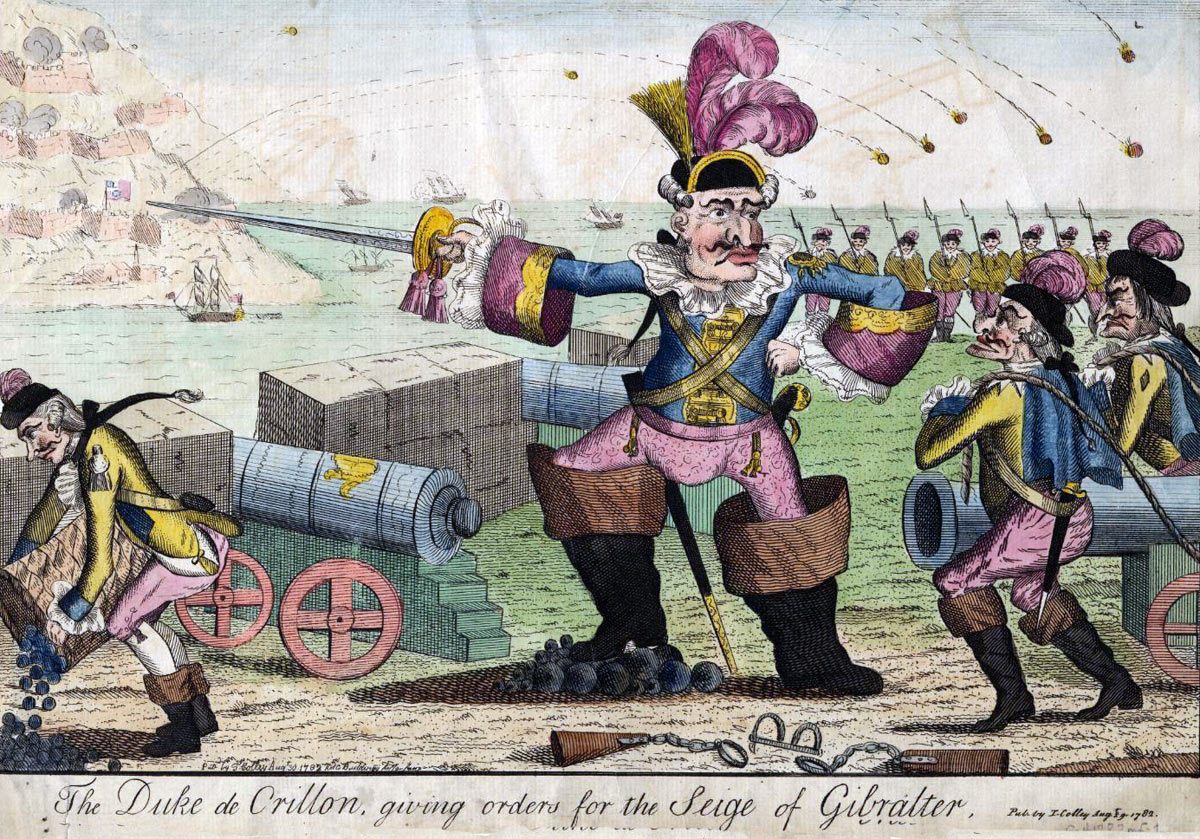

The Duc de Crillon commanded the armies besieging Gibraltar from March 1782.

Admiral Barcelo commanded the Spanish ships in Algeciras during the siege, until the concentration took place for the Attack by the Battering Ships.

Winner of the Siege of Gibraltar: The British successfully defended Gibraltar throughout the siege.

Background to the Siege of Gibraltar:

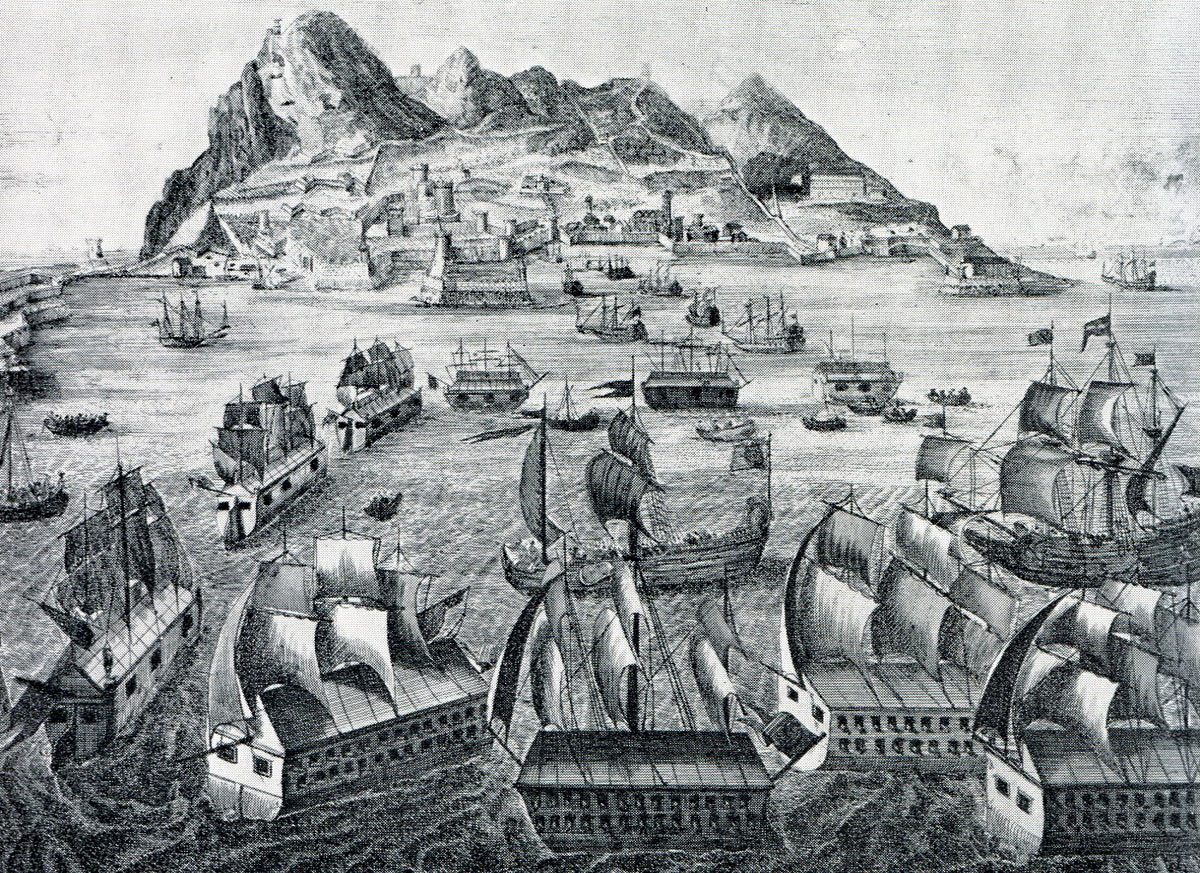

The isthmus of Gibraltar, in the south of Andalusia, the southernmost province of Spain, became a British possession on its capture by a mixed British and Dutch naval and military force in 1704.

By the Treaty of Utrecht, ending the War of the Spanish Succession, Spain ceded Gibraltar to Great Britain in perpetuity.

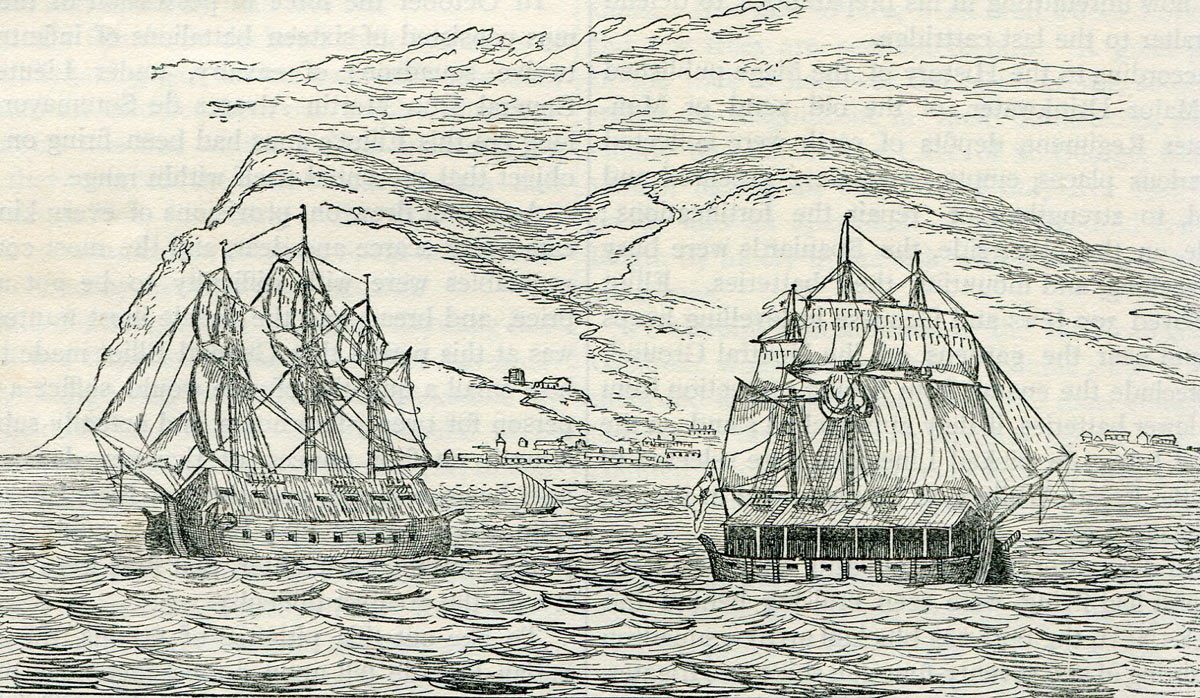

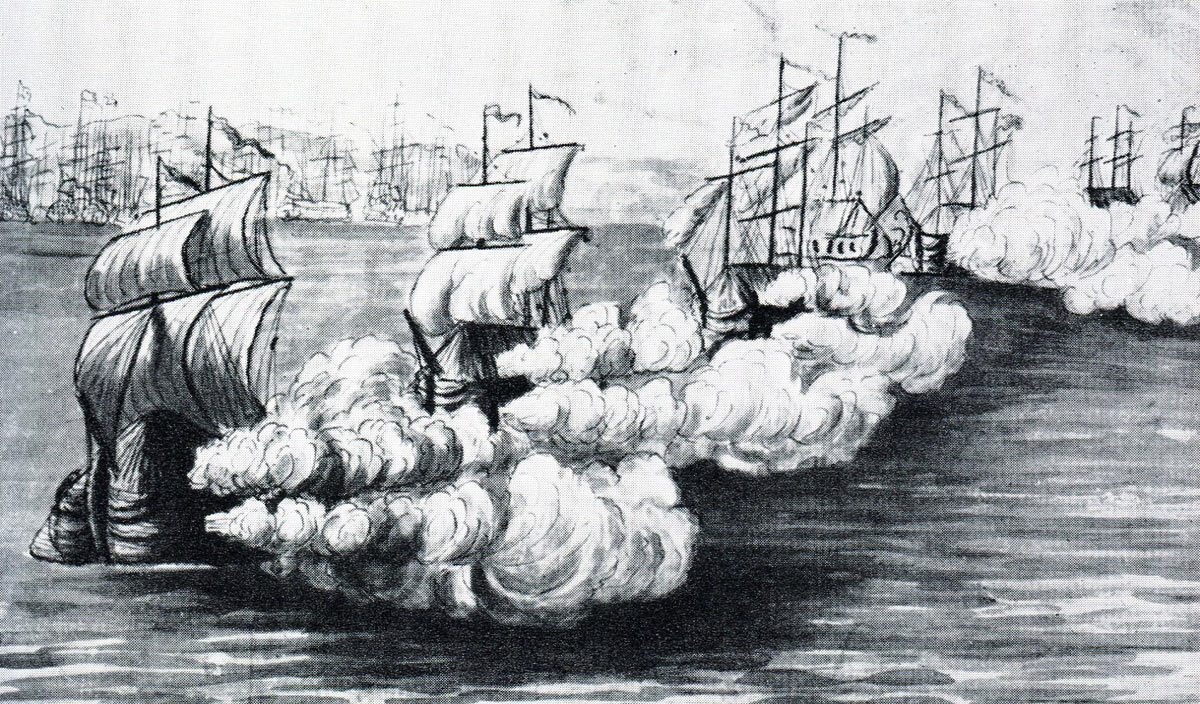

British and Dutch capture of Gibraltar in 1704: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The cession of Gibraltar to Great Britain did not reconcile the Spanish monarchy and establishment to the permanent loss of Gibraltar and, during the 18th Century, frequent diplomatic initiatives were conducted by Spain to recover Gibraltar. Two major attempts were made by Spain to recover Gibraltar by military means, one in 1727 and the other in 1779.

Jewish woman resident of Gibraltar in her finery: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

With the capture of Gibraltar by the British in 1704, the Spanish population left. Under British rule a new population established itself, mainly Jewish refugees from around the Mediterranean area and settlers from the Italian city of Genoa. There was a substantial British military garrison on Gibraltar from 1704.

The 1727 Spanish siege of Gibraltar lasted a few months with no attempt to mount a blockade.

Between 1755 and 1763, Great Britain fought the Seven Years War (the French and Indian War in North America) against France and Spain. Ended by the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the war saw France lose Canada, her foothold in India, islands in the West Indies and territory in West Africa. Spain lost to Britain, Florida, Manilla in the Philippines and Havana on Cuba. Manilla and Havana were returned to Spain under the Treaty of Paris, but Florida was retained.

With the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1765 and the increasing difficulty Great Britain experienced in combating the revolt in the Thirteen American Colonies, both France and Spain saw the opportunity to exact revenge for the humiliations of the Seven Years War and to recover lost territory.

For Spain, the territory in the Mediterranean to recover from Great Britain was Gibraltar and the island of Minorca.

Port Mahon on Minorca: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

France and Spain entered the war against Great Britain in 1778 and 1779 respectively, followed by the Netherlands and a federation of other northern states.

While Great Britain’s Royal Navy was a powerful and growing force, it had not reached the dominance it achieved at the end of the century and struggled to counter the strong and often well-led French Navy, allied to the large but somewhat ramshackle Spanish Navy. The presence of a strong Dutch Navy in the North Sea stretched the Royal Navy still further.

The British Army struggled to recruit the troops Britain needed to fight the Americans, defend the West Indies against the French and Spanish, combat the French in India and maintain a sufficient strength to retain Gibraltar and Minorca in the Mediterranean; all against a fundamental requirement to defend Britain and Ireland from invasion by France and Spain.

The Rock of Gibraltar seen from the north: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by William Ashford

The problems of recruitment were severely hampered by the lack of popular support for the war to suppress the American colonists, seen by many in Britain to be fighting for essential liberties.

Cross Belt Plate of the 72nd Royal Manchester Volunteers: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: the 72nd Royal Manchester Volunteers Regiment only existed for 5 years but spent that time serving in one of Britain’s most dramatic military episodes

Recruitment Poster for the 72nd Royal Manchester Volunteers: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

Once the war widened to bring in France and Spain, the popular view in Britain changed fundamentally. The war was now a national struggle for survival. Recruitment increased, but too late to retain the American colonies.

In Manchester, a new regiment was raised, the 72nd Royal Manchester Volunteers, specifically for service in defending Gibraltar against Spanish attack. Such was the enthusiasm that the regiment was fully recruited to around 1,000 officers and men in a few weeks.

Captain John Drinkwater took a commission as an ensign in this regiment at the age of 15 and went on to write the definitive account of the Siege of Gibraltar from his journal, compiled during the siege.

Another ‘War Service’ regiment that served in Gibraltar was the 2nd/73rd Highland Regiment. The 1st Battalion of this regiment was serving in India and survived the war, being re-numbered 71st and going on to become the 1st Battalion of the Highland Light Infantry.

The Siege of Gibraltar; the garrison of Gibraltar:

On 25th May 1777, Lieutenant General George Augustus Eliott arrived in Gibraltar to take up the post of governor.

Eliott was born on 25th December 1717, in Roxburghshire in Scotland, a younger son to a baronet. Eliott was educated at Leyden in Holland and at Vauban’s Military Engineering college at La Fère in Picardy in France, before serving in the British Army in turn as an engineering, cavalry and infantry officer.

Eliott’s 15th Light Dragoons in 1760: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

Eliott served through the War of the Austrian Succession, fighting at the Battle of Dettingen in 1743, where he was wounded and the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745. In the Seven Years War, in 1759, Eliott raised the 15th Light Dragoons. At the Battle of Emsdorff in 1760, the 15th captured five battalions of French infantry and nine guns. In 1762, Eliott served as second in command to the Earl of Albemarle at the capture of Havana in Cuba. Eliott’s share of the prize money for the capture of Havana enabled him to buy the estate of Heathfield in Sussex.

Sergeant Major in the Soldier Artificer Company: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Richard Simkin

Sixty years of age on his appointment as governor of Gibraltar, Eliott was an austere man, vegetarian and teetotaller, who regularly slept for only four hours a night. He suffered from gout. He was considered a strict but fair disciplinarian.

Eliott became governor of Gibraltar at a time of increasing threat from Spain, whose King Charles III cherished the ambition of recovering Spain’s lost territories of Gibraltar and Minorca. Eliott’s determined character, with his extensive military and military engineering experience, made him uniquely qualified to command the garrison in Gibraltar during the Siege.

During the period of peace following the end of the Seven Years War, the defensive capability of Gibraltar was allowed to run down, the fortifications falling into disrepair, the garrison reduced, guns inadequate in numbers and condition and supplies of food and ammunition left to run low.

On Eliott’s arrival, he set to work to remedy these failings and ensure that the garrison could resist what was increasingly seen as an inevitable Spanish attack.

Eliott was assisted by resourceful and capable senior officers; in particular, the deputy governor, Lieutenant General Boyd and the chief engineer, Lieutenant Colonel William Green.

At Green’s suggestion, his team of skilled and semi-skilled

Major General Sir William Green in later life, with Gibraltar seen through the window: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

engineers were, in 1772, formed by warrant into the Soldier Artificer Company, the forerunner of the Corps of Royal Engineers. This company was to provide an essential service in building, re-building and maintaining the batteries and fortifications, under prolonged and heavy bombardment during the Siege.

On Eliott’s arrival, the size of the garrison was around 4,000 men. Eliott’s view was that the minimum was 8,000 men. The numbers did not rise much above 5,000 during the Siege. The initial step taken was to bring the Gibraltar regiments up to the British establishment, effectively authorising each regiment to be augmented from around 500 men to 1,000 men, although such an increase was not achieved in full.

Additional regiments were sent to Gibraltar during the Siege.

The main physical task facing Eliott was an extensive building programme of new fortifications for Gibraltar, as set out in a report by a Commission that had examined the state of the Rock’s defences in the early 1770s.

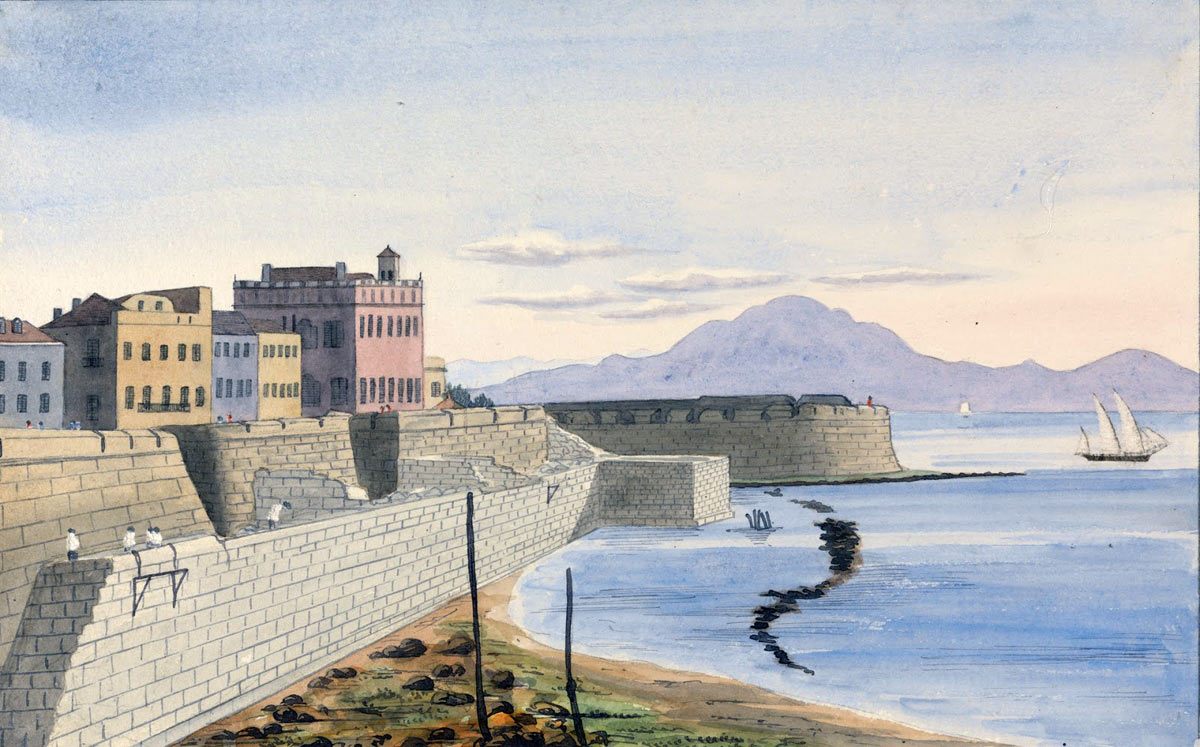

King’s Bastion Gibraltar under construction, with Dejbal Musa on the Moroccan African coast in the distance: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The most prominent new work was the King’s Bastion, built by Green and his engineers on the main waterfront of the town in Gibraltar. The King’s Bastion comprised a stone battery holding twenty-six heavy guns and mortars, with barracks and casemates to house a full battalion of foot.

The Grand Battery protected the Land Port Gate, the main entrance to Gibraltar from the isthmus leading to the Spanish mainland. Other fortifications and batteries crowded along the town’s waterfront and on the Rock.

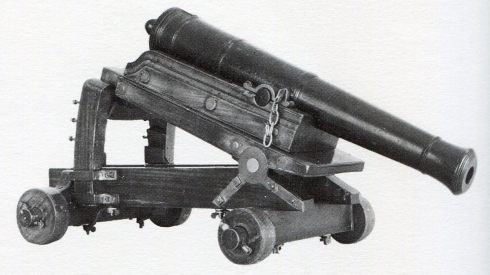

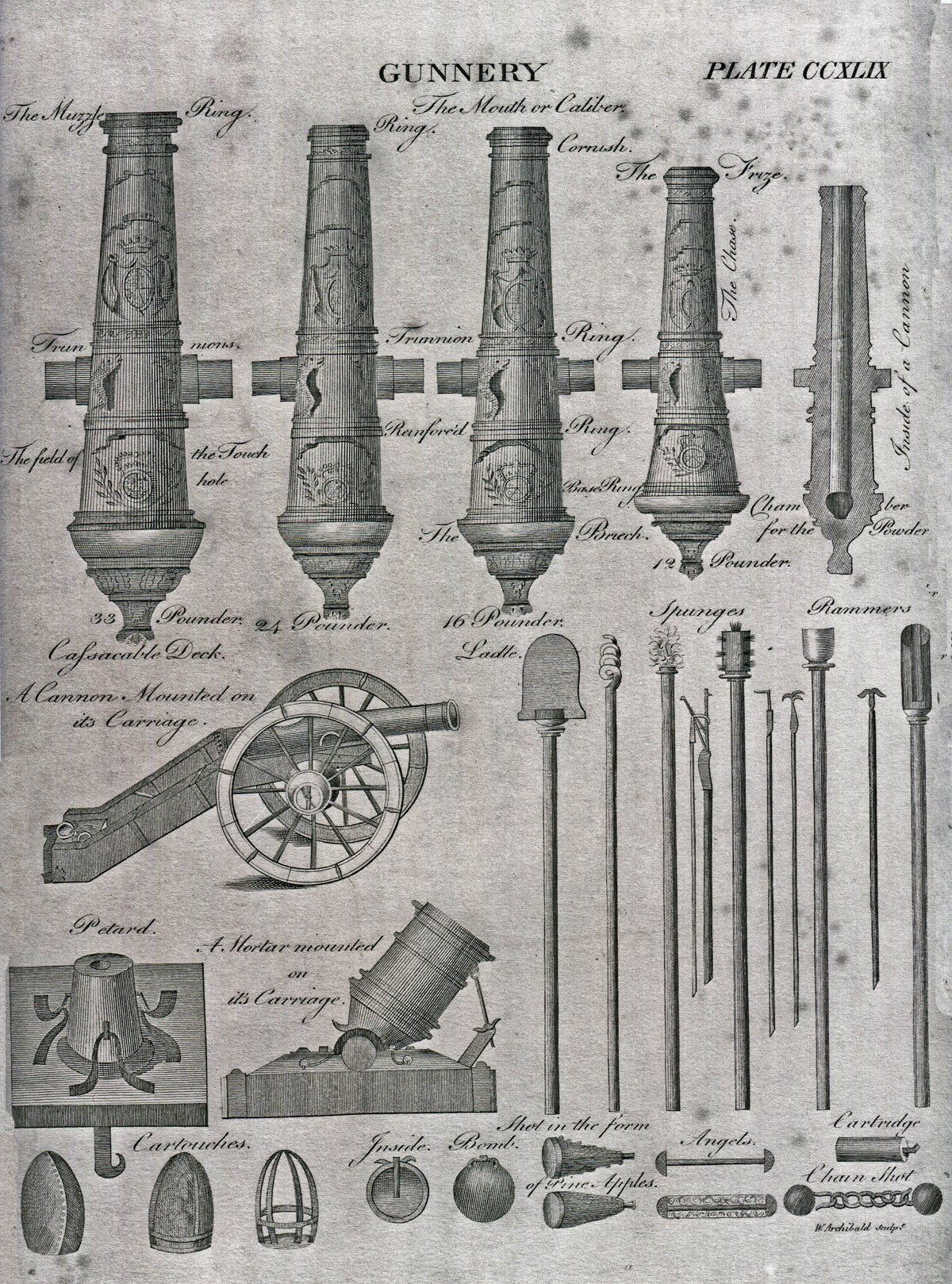

Eliott began a programme of increasing the number of guns deployed in the batteries and fortifications, which initially stood at 412; a significant proportion of which were incapable of use. By the end of the Siege, Gibraltar was defended by 663 large pieces of ordnance, able to fire heavy calibre rounds up to a mile out to sea in every direction.

A significant feature of the Spanish plan was to blockade Gibraltar. The ease of access to Gibraltar, from the Mediterranean to the east and from the Atlantic to the west, was to be a considerable stumbling block to the Spanish. Throughout the Siege, a steady stream of blockade running vessels, from a wide range of ports, provided the Gibraltar garrison with their supplies.

Spanish zebec vessels closing in on a blockade runner sailing into Gibraltar: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The blockade runners, although important, could not provide the large garrison with anything like its needs in food and ammunition. The re-supply that preserved Gibraltar was effected by the three relief fleets brought from England by the Royal Navy; Rodney’s in 1780, Darby’s in 1781 and Howe’s in 1782.

The Siege of Gibraltar; preparations:

Following the surrender in America of General Burgoyne’s British army at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777, the French entered the war in 1778 on the side of the American colonists, against the British.

On 16th June 1779, the Spanish issued what was in effect a declaration of war against Great Britain.

Beginning of the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: print by John Martin Will

News of the outbreak of hostilities between Britain and Spain reached the Spanish governor at San Roque, the nearest town to Gibraltar, Lieutenant General Don Joaquin Mendoza, in mid June 1779 and subsequently reached Gibraltar.

General Eliott put his garrison on a war footing and assembled a council of war. Mr Logie, the British consul in Tangier, returned from Gibraltar to his post in Morocco, to organise the regular provision of supplies for the garrison.

Arrangements were made to ship as many of the civilian residents out of Gibraltar as possible, sending them in the vessels that brought in supplies. Ships were moved from the Old Mole at the northern end of the town, to the New Mole at the southern end, where they were less vulnerable to Spanish gunfire.

The naval squadron in Gibraltar was commanded by Rear Admiral Robert Duff and comprised HMS Panther (60 guns), three frigates, HMS Enterprise and a sloop of war.

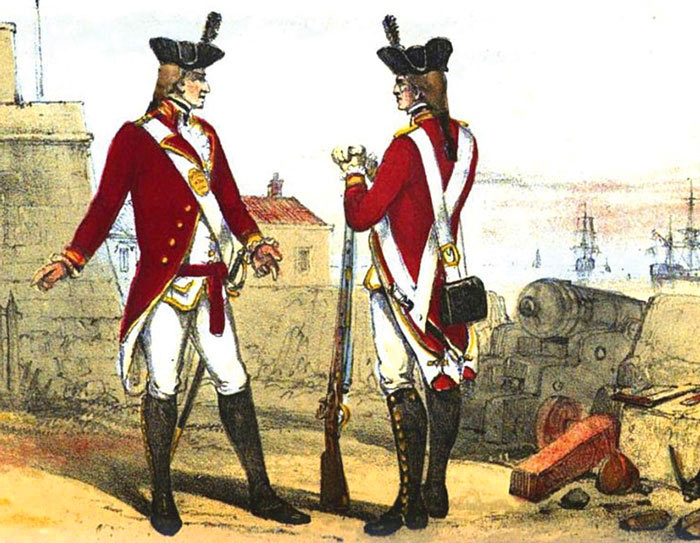

British troops: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Richard Simkin

The military garrison in Gibraltar comprised the British 12th Regiment, 39th Regiment, 56th Regiment, 58th Regiment and the 72nd ‘Royal Manchester Volunteers’; Hanoverian Regiments, Hardenburg’s (later Sydow’s), De La Motte’s and Reden’s; a Brigade of Marines, the Soldier Artificer Company and five companies of Royal Artillery. The total number of the garrison was 5,382 men.

Eliott transferred 180 volunteer infantry soldiers to the Royal Artillery companies, to augment the existing 485 gunners. While the guns of some batteries were manned full time, the gun crews moved around the others, when they were required to be brought into action.

The garrison’s guns comprised seventy-seven 32 pounders, one hundred and forty-nine 24 and 26 pounders, one hundred and thirteen 18 pounders, seventy-four 12 pounders, one hundred and six smaller calibre guns, one hundred mortars and twenty-nine howitzers.

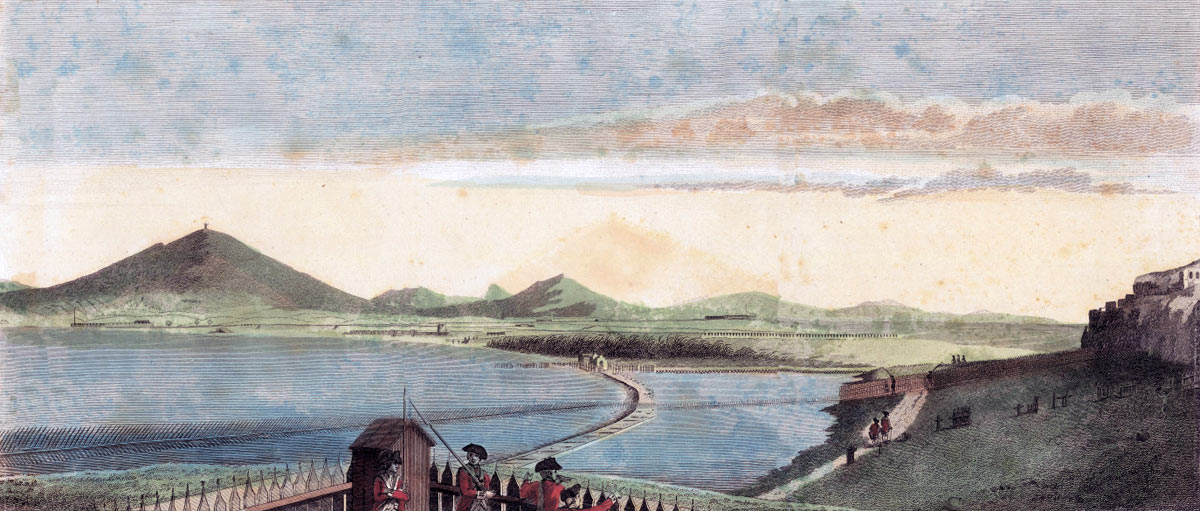

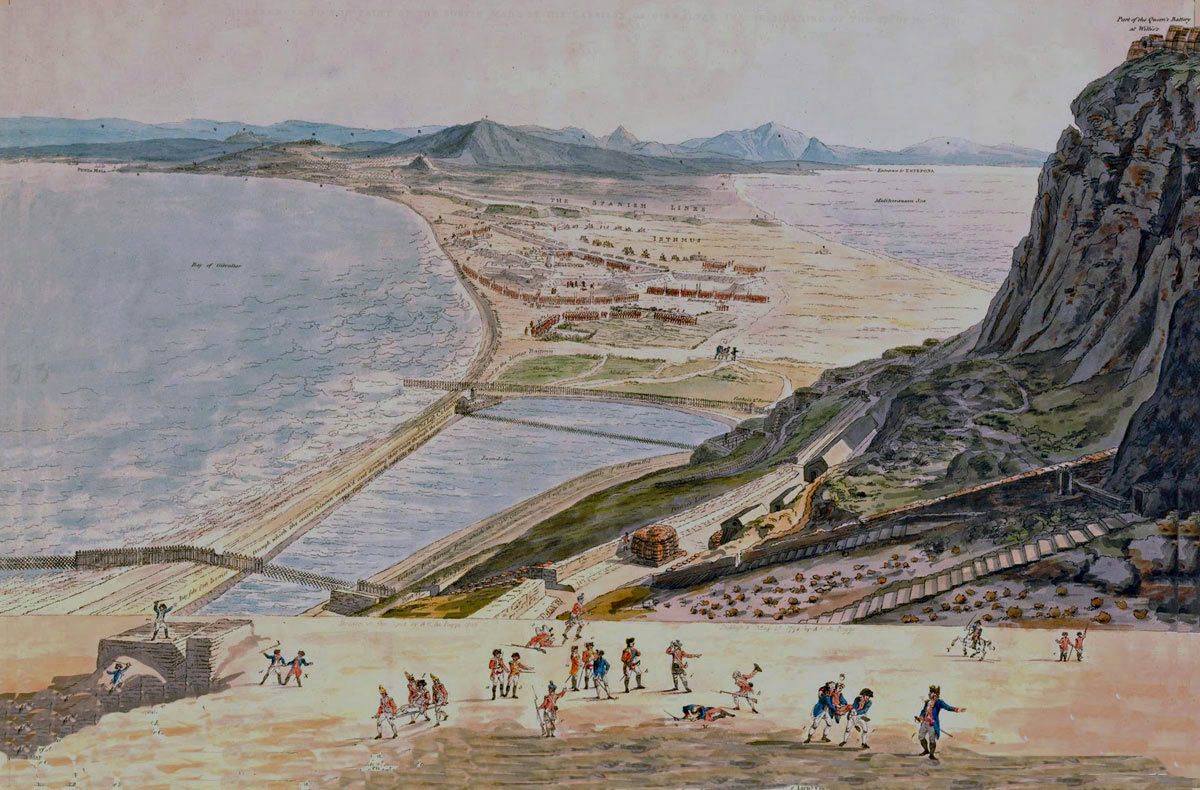

View over the Land Port Gate from Gibraltar towards the Spanish siege works: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The Siege of Gibraltar; the blockade:

On 6th July 1779, an engagement took place between British ships and Spanish vessels bringing supplies to the Spanish troops on shore. Several Spanish vessels were taken and the hostilities began. By 18th July 1779 the Spanish were closely blockading Gibraltar.

The Spanish blockade over the period of the Siege of Gibraltar, from July 1779 to 2nd February 1783, followed the same general pattern, although varying widely in intensity and effectiveness. The Spanish squadron based at Algeciras, across the bay from Gibraltar, mounted patrols in the bay and around Gibraltar, intercepting, with varying degrees of success, the blockade running ships bringing supplies to the garrison.

Spanish gunboats off Rosia: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: sketch by Captain Spilsbury

The Spanish squadron at Algeciras comprised, for much of the Siege, two or more 74 gun ships of the line, two or three frigates, several felucca-rigged vessels with up to 32 guns, several galleys and up to twenty armed boats, all manned by over 6,000 Spanish sailors.

Royal Artillery gunner: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Richard Simkin

At night, Spanish gun boats would roam around the Gibraltar shore and fire into the defences and moored ships. Many of these vessels were armed with a single long barrelled 18 pounder gun, having a greater range and being more accurate than the standard British 18 pounder.

Although at times the British garrison suffered extreme privation, a stream of ships of different nationalities reached safety in Gibraltar.

During the Siege, General Eliott sent a stream of dispatches to London, by any suitable available vessel. All but one reached their destination, providing the British government with a regular update of the garrison’s condition and needs.

On Sunday 12th September 1779, the British guns on the North Face of the Rock opened fire on the Spanish across the Isthmus. In a battery on the North Face, Mrs Skinner, the wife of an Engineer officer, fired the first gun, on the governor’s direction, while a band played ‘Britons strike home’. In the New Battery, Captain Lloyd fired the first shot.

From then on, guns on Gibraltar were firing at the Spanish lines and ships, day and night, throughout the Siege.

The British artillery officers were given a complete discretion when and where to fire on the Spanish. It is said that one officer began his tour of duty by having every gun in his battery fire simultaneously.

Ships, passing through the Straits of Gibraltar, became used to seeing the Rock wreathed in smoke and hearing the rumble of constant gunfire, with flashes at night.

In the early days, the Spanish did not respond to the British gunfire and, once they realised that there was little danger of being hit, the Spanish soldiers working on the siege works gave up taking cover and carried on with their tasks.

The Siege of Gibraltar; the first relief by Admiral Sir George Rodney, following the Battle of Cape St Vincent or the ‘Moonlight Battle’:

Admiral George Rodney: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

By November 1779, the Gibraltar garrison was running short of food. Attempts to resume the tending of vegetable patches on the isthmus were prevented by Spanish gun fire. Soldiers and civilians were permitted to grow food on the sides of the mountain to the south of the Rock.

On 15th January 1780, a Royal Navy brig arrived from the Atlantic, evaded the blockading Spanish vessels and came in to the New Mole. She brought news that a large convoy from England was approaching, escorted by the Royal Navy.

The garrison of Gibraltar heard the news with delight and the wine shops, long closed to prevent disorder, opened for celebrations.

It was noticeable that the Spanish Admiral Barcelo’s flotilla was not going out to sea to meet the incoming ships, but was keeping well in to harbour at Algeciras and attempting to put a protective boom in place.

During the evening of 16th January 1780, the British ships began to arrive in Gibraltar harbour with news of a substantial naval victory over the Spanish fleet.

Admiral Sir George Rodney commanded the British fleet, which had left the English Channel at the end of December 1779 and sailed south, with a substantial convoy of merchant ships, loaded with supplies for the British garrisons of Gibraltar and Minorca, including ammunition and troop re-inforcements.

Rodney’s Royal Navy fleet comprised 22 large men of war, 14 frigates and several smaller ships.

Among the ships, both Royal Navy and merchant, were vessels for the West Indies.

On 7th January 1780, the ships for the West Indies left the fleet and headed west.

On 8th January 1780, Rodney’s ships sighted a Spanish convoy of 22 ships, carrying supplies for the Spanish fleet in Cadiz. The British pursued the Spanish ships and captured the entire fleet, which included 7 warships, one of 64 guns. These ships were added to the Gibraltar convoy.

The British practice of sheathing the bottoms of warships with sheets of copper made them significantly faster than the Spanish ships, with their be-fouled wooden bottoms.

Soon after this successful action, passing ships informed Rodney that a strong Spanish squadron was sailing off Cape St Vincent. Rodney prepared his warships for battle and sent the merchantmen on into Gibraltar.

Rodney’s ships sighted the Spanish squadron, which comprised 11 ships of the line and two 26 gun frigates, during the afternoon of 16th January 1780, the day the merchantmen were beginning to arrive in Gibraltar and immediately attacked, the Spanish ships accepting battle.

Don Juan de Langara, Spanish Admiral at the ‘Moonlight Battle’ on 16th January 1780: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

By the time the battle started, at 4pm, a substantial and increasing storm was blowing and the two fleets were near to shore, with the wind blowing towards the land. Early in the battle, the Spanish 70-gun ship San Domingo blew up, with all her crew lost and another Spanish ship struck her colours.

The battle continued after dark, giving rise to its title of ‘Rodney’s Moonlight Battle’.

During the night, several Spanish ships of the line were captured. Of these, two were blown ashore.

One of the captured Spanish ships was the Phoenix, the flagship of the Spanish Admiral, Don Juan de Langara, who was wounded.

Rodney’s flagship, HMS Sandwich, ran alongside a Spanish ship, the Monarch and poured in a single broadside, at which the Spanish ship hauled down her colours.

By morning, the battle was over, with four Spanish ships of the line in British hands and two more wrecked on the shore.

During the battle, a further fleet of 20 Spanish and 4 French warships lay in Cadiz harbour, but did not come out to sea to assist de Langara’s squadron. Nor did the Cadiz fleet make any attempt to interfere with Rodney’s ships while they were in Gibraltar.

Rodney’s ‘Moonlight Battle’ on 16th January 1780: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: the Spanish ship San Domingo explodes in the background early in the battle

The Gibraltar garrison watched as the store ships arrived in harbour, followed by Rodney’s warships, in the period up to 26th January 1780.

On board the troopships was the Second Battalion of the 73rd, a Scottish Highland regiment, recently raised and bound for Minorca. This battalion would have sailed directly on to Minorca, without stopping at Gibraltar, but the soldiers were distributed around the British ships as marines, after the crews were diluted by the need to man the Spanish ships captured in the first action, requiring the men to be landed in Gibraltar, to return them to their troops ships. This enabled Eliott to retain this strong battalion of 900 Highlanders to augment his garrison.

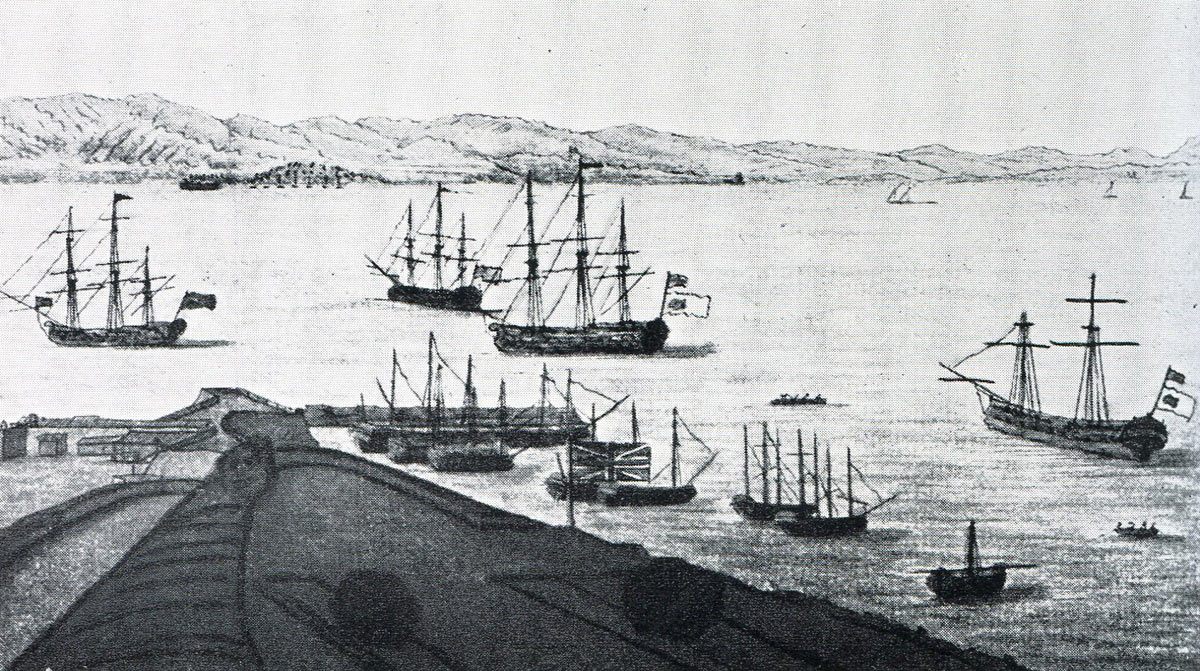

Admiral Rodney’s squadron remained in Gibraltar until 13th February 1780, while the stores were unloaded from the merchantmen, giving Eliott supplies for a further six months to a year depending on the commodity.

New equipment was issued to the garrison, many of the soldiers being sorely in need of replacement uniforms and boots. The 72nd was particularly poorly dressed.

Admiral Rodney’s ships off the New Mole in Gibraltar: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: the ships on the right and in the centre are captured Spanish ships with British colours over Spanish colours: eye witness sketch by Captain John Spilsbury

The captured Spanish warships were plundered for heavy guns and stocks of gunpowder and ammunition, although, on testing, the Spanish powder was found to be inferior to British powder.

Eliott seized the opportunity of Rodney’s departure to get rid of the ineffectual Admiral Duff, who returned to England and obscurity.

During the stay of Rodney’s fleet, the Spanish forces on the mainland were in much reduced circumstances as their regular re-supply by coastal sea traffic was halted. Increased numbers of Walloon deserters described shortages of food and the flooding of the Spanish siege works.

Admiral de Langara and other Spanish naval officers were released on parole, to return home. The courteous treatment they received in Gibraltar brought about improved treatment by the Spanish for British prisoners.

Admiral Rodney’s ships in Gibraltar in January 1780: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Dominic Serres

Due to the demands made on Rodney’s crews to provide manning for the captured Spanish ships and sickness among HMS Edgar’s crew, the admiral was forced to leave HMS Edgar in Gibraltar, providing Eliott with a welcome increase in his naval strength, which now comprised in addition to Edgar: HMS Panther, frigates Enterprise and Porcupine and sloops Gibraltar and Fortune. Edgar remained until her crew recovered and she left on 20th April 1780.

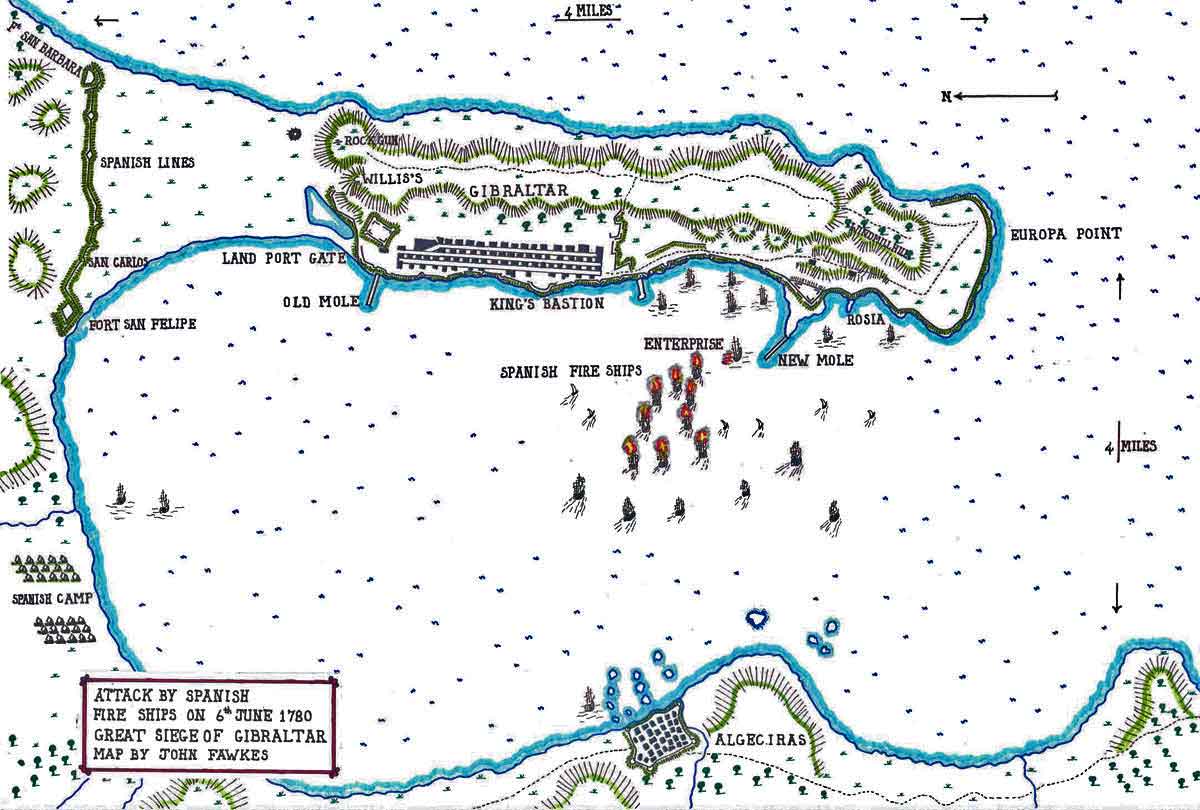

Map of the Spanish Fire Ship attack on the night of 6th/7th June 1780: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

The Siege of Gibraltar; the Spanish attack with fire ships:

On 4th June 1780, the Gibraltar garrison celebrated the birthday of King George III with a 42-gun salute and the governor gave a dinner for his officers of field and general rank.

At around 1am on the night of 6th/7th June 1780, an unidentified ship approached the New Mole on a moderate wind through the darkness, heading towards the huddle of British ships close in to the shore.

HMS Enterprise hailed the approaching ship, requiring her to identify herself and received the information ‘Fresh beef from Barbary’, a very welcome cargo, if true.

However, Enterprise, alert and suspicious, fired the three-gun alarm signal and opened fire on the ship, which immediately burst into flames. Several ships, following the first towards Gibraltar harbour, also burst into flames. It was the expected Spanish fire ship attack and nine ‘tall mountains of fire’ were drifting towards the anchored British shipping.

The Spanish Fire Ship attack on the night of 6th/7th June 1780: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

Drums roared through the Gibraltar camp and the emergency drill was immediately put into action. HMS Enterprise cut her cable and put further in to shore, under a shower of burning embers, which her crew quickly extinguished.

The British batteries in the area opened fire on the now abandoned Spanish fire ships, while Royal Navy crews took to their boats and, grappling the fire ships, began to tow them away from the shipping.

In the bay, Admiral Barcelo’s squadron followed the fire ships, to pick up the crews and attack any British ship forced out of the harbour.

Two of the fire ships were turned and pushed out into the bay, while the rest beached towards Europa Point. No damage was caused, although one of the ships, burning fiercely, passed close to HMS Panther at anchor. The beached ships continued to burn through the next day.

The Spanish Fire Ship attack on the night of 6th/7th June 1780: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The practice in the preparation of fire ships was to place barrels of gunpowder low down in the ship, ready to explode when the fire reached them, thereby making any countering operation particularly hazardous. The Spanish did not use this device, perhaps through a shortage of ammunition.

The Spanish batteries on the main land failed to take advantage of the attack and open fire on Gibraltar, presumably due to a lack of co-ordination between the Spanish navy and army, with Barcelo concerned to preserve the secrecy of his attack and deeply suspicious of his military colleagues.

In the end, other than causing considerable alarm in Gibraltar, the Spanish fire ship attack achieved little, other than the loss of the nine fire ships, one of which was a Spanish 50-gun warship.

In the middle of the turmoil over the fire ships, a blockade runner sailed through the Spanish squadron into Gibraltar harbour, carrying poultry and leather.

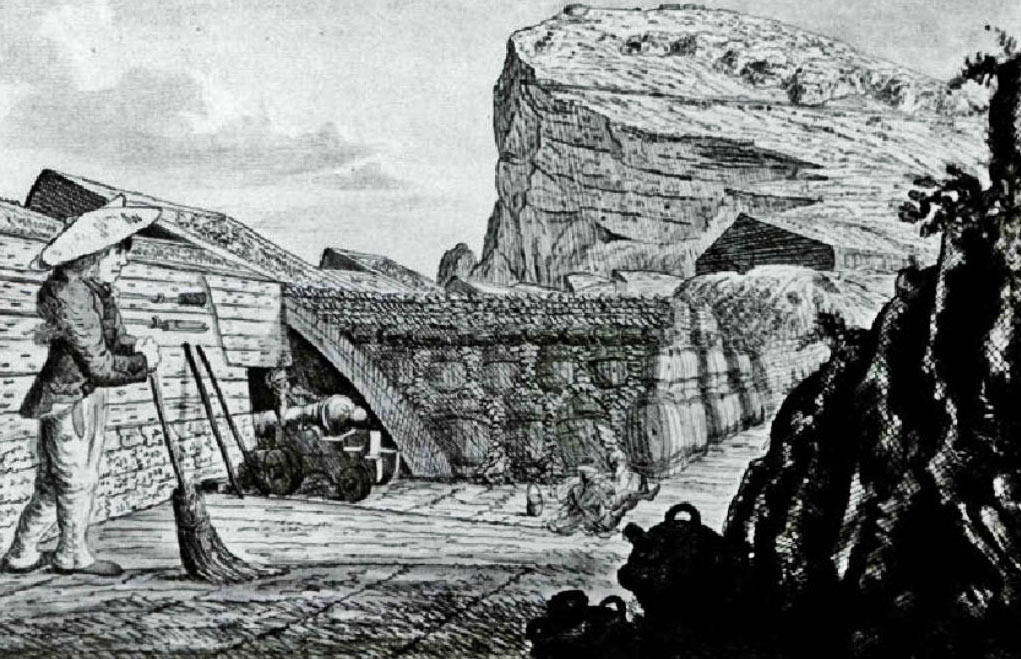

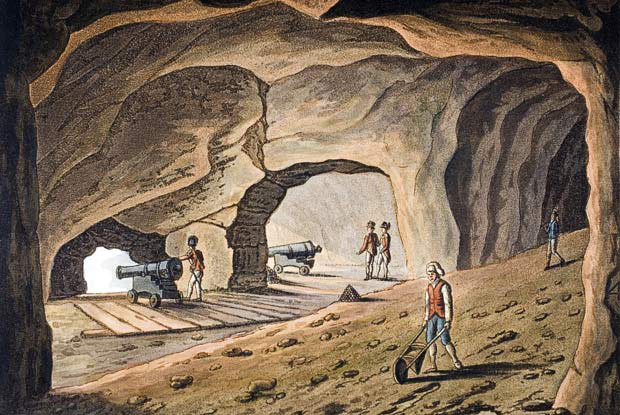

Inside Willis’s Battery: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: the gun in the picture is on Koehler’s ‘depressing gun carriage’ enabling it to fire down into the Spanish Siege Works

The Siege of Gibraltar; the second blockade:

In July 1780, HMS Panther sailed for England with 100 British seamen recovered from wounds suffered in the Moonlight Battle of 16th January 1780.

The next crisis to strike the garrison was a smallpox epidemic, that by August 1780 had killed 450 residents and military family members and 50 soldiers.

Following the relief of Gibraltar by Admiral Rodney’s fleet, the Spanish imposed an even stricter and more rigorous blockade on Gibraltar.

The firing of guns from the Gibraltar fortifications became desultory. Only six shots were fired from the shore based Gibraltar guns in the months of August and September 1780.

On 29th August 1780, the commanding officer of the 72nd Royal Manchester Volunteers, Colonel Charles Mawhood, died of ‘the stone’ and was buried with full military honours. Mawhood had made his name in the early fighting in America, particularly as the commanding officer of the 17th Regiment at the Battle of Princeton on 3rd January 1777. As a result of his reputation in America, Mawhood was given the honour of raising the 72nd.

The Siege of Gibraltar; the second relief by Vice Admiral George Darby:

Vice Admiral George Darby, commander of the Second Relief Fleet: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

At the end of August 1780, the Emperor of Morocco, concluding that the Spanish would capture Gibraltar and win the war, permitted them to seize all the ships waiting in Moroccan ports to run the blockade to Gibraltar.

British subjects were attacked in the streets of Tangier.

The British consul in Tangier, Mr Lorie, an invaluable source of intelligence and supplies for Eliott, was forced to leave Morocco and with the other British nationals arrived in Gibraltar by ship.

Supplies for the Gibraltar garrison became scarcer, with biscuit replacing bread and a lack of fresh vegetables, fresh meat and fruit, leading to an increase in scurvy.

The Spanish forces outside Gibraltar became more active and emboldened, building siege works down the Isthmus and establishing more breastworks.

The Spanish gunboats began to prey on the Gibraltar fishing craft. At night, the same gunboats approached the ships moored along the waterfront of Gibraltar town and fired on them.

To counter this move, in November 1780, a boom was constructed to enclose the area by the New Mole where most of the ships were anchored.

Eliott caused the gunfire to be increased on the developing Spanish siege works.

In early 1781, Eliott attempted to maintain the morale of his regiments by holding a series of field days and by introducing prizes for soldiers who observed new activity by the Spanish in the siege lines.

With food becoming increasingly scarce, Eliott, on advice, decided to send all the invalids, in the two ships Enterprise and St Fermin, to Minorca, which was not as yet under Spanish attack. With the ships, Eliott sent a letter to the British governor on Minorca, General Murray, requesting that he send all the naval vessels he could spare with any surplus supplies. On the journey, St Fermin was taken by Spanish zebecs and the invalids on board became prisoners.

Gibraltar from the Spanish lines with a Spanish zebec on the right: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

Much of the Spanish fleet was kept in Cadiz, to the west of Gibraltar, the intention being to intercept any attempt to re-supply the British garrison.

In January 1781, Eliott heard from England that a second relief convoy was under preparation.

Convoys of merchant sailing ships took a considerable time to assemble and it was not until 13th March 1781 that the relieving fleet sailed from the Scilly Isles, at the south-western corner of the English Channel, under Admiral George Darby in the 100 gun HMS Britannia.

Darby’s fleet picked up ships for the West Indies and America off Cork and then turned south towards the Mediterranean, dispatching the smaller convoys to the west.

Man of War approaching Gibraltar: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Thomas Whitcombe

By 10th March 1781, Darby’s fleet of 29 ships of the line and 100 store ships was sailing down the south-west coast of Spain, with no attempt being made to interfere by the Spanish fleet in Cadiz.

Darby’s fleet reached Gibraltar on 12th April 1781. A small section of the fleet sailed on to Minorca, while the preponderance unloaded at Gibraltar.

As with the arrival of every one of the three relief fleets, the Gibraltar garrison was warned of the convoy’s approach by the increased activity in the Spanish lines, with signal flags and movement of guns and ships and the building of new batteries.

The day of Darby’s arrival was shrouded in fog. As the fog lifted, first the mast tops and then the entire fleet came into sight, lifting the spirits of the watching garrison immeasurably.

The Spanish gunboats advanced to attack the merchant ships, but were seen off by a British ship of the line and two frigates, several of the gunboats running ashore on the rocks in their flight. The ships of the convoy docked safely in Gibraltar.

On 21st April 1781, Darby sailed for England with dispatches from Eliott. The Gibraltar garrison was thoroughly re-provisioned, without there being any interference by the Spanish navy.

Chart showing the sizes of gun and types of ammunition: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The Siege of Gibraltar; the Great Bombardment:

The expectation of the Spanish high command was that the Gibraltar garrison was at the end of its supplies and would soon be forced to surrender. The arrival of Darby’s second relief on 12th April 1781 appeared to exasperate the Spaniards.

As the unloading of the store ships brought into Gibraltar by Admiral Darby’s fleet began, the Spanish opened fire with the newly installed batteries, equipped with some 114 heavy guns, firing on the Land Port Gate, the town and the waterfront, as well as the other installations and buildings on Gibraltar. The British responded with counter-battery fire, particularly against the San Carlos battery, which slowly reduced its response.

The Spanish firing continued throughout the day and the following night, with the customary siesta break from 1pm to 5pm.

The whole of Gibraltar was raked with cannon-fire and a great deal of damage was inflicted on the town, but little damage was done to the ships.

Gibraltar town damaged by Spanish cannon fire: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

A major and unexpected feature of the Spanish bombardment was that the destruction of the houses in Gibraltar town revealed the extent to which the civilian population had been hoarding supplies and, in particular, drink. The British troops indulged in an orgy of indiscipline, in which these supplies were ransacked and the streets filled with drunken soldiers looting the houses.

Eliott sent the town major into the streets with a party of well-disciplined troops, to destroy all the stores of alcohol they could find. Soldiers found looting were hanged on the spot. Slowly discipline was re-established.

From the arrival of the second relief fleet, the Spanish bombardment continued at a much-raised intensity for the rest of the siege, except for the months of July and August 1782, when the Spanish were reserving their ammunition and effort for the ‘Floating Battery Attack’.

British guns in action on Gibraltar: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by W.H. Overend

Otherwise, thousands of rounds were fired by the Spanish into Gibraltar each month and the British replied in kind. It is estimated that in the first seven weeks of the bombardment both sides fired 77,000 rounds.

In the end, the statistics of ammunition fired cease to have much meaning. For the rest of the siege, day and night, Gibraltar rumbled to the discharge of guns and the sky lit up to the flashes of gunfire, with palls of smoke wreathed around the Rock and the surrounding coastal area.

12. Podcast of The Great Siege of Gibraltar, between 8th July 1779 and 2nd February 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

12. Podcast of The Great Siege of Gibraltar, between 8th July 1779 and 2nd February 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

At Eliott’s request, Admiral Darby, when he sailed for England, left several naval vessels and store ships for the garrison and a large quantity of gun powder from the fleet’s stores to sustain the now near constant bombardment of the Spanish lines. Darby commented that ‘The Garrison of Gibraltar is a very grand object’, mirroring the general view in Britain.

The range of many of the Spanish guns surprised the garrison, the whole of Gibraltar to the southern tip of Europa Point being under fire.

On the highest point of the north face of Gibraltar, the ‘Rock Gun’, a 24 pounder, was positioned. A Spanish battery of seven guns was devoted to repeatedly disabling this gun and forcing its replacement.

Gibraltar town badly damaged by the Spanish bombardment: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Captain Thomas Davis

With the sustained bombardment, it was found that many of the defensive works in Gibraltar were inadequate to keep out the heavy calibre rounds the Spanish were firing.

Spanish gunboats ranged along the coast and fired into the assembled British shipping with their single long 18 pounders.

On 27th April 1781, the Royal Navy ships, HMS Enterprise and the frigates HMS Brilliant and Porcupine, arrived from Port Mahon on Minorca, leaving additional supplies before sailing on to England, other than Brilliant, which remained in Gibraltar with her captain, Roger Curtis, an active and resourceful officer in the subsequent defence, becoming a close associate of General Eliott.

The garrison flag was flown from the Grand Battery and attracted considerable Spanish fire. It was a point of honour to maintain the flag, which had to be replaced repeatedly after being struck down.

On the King’s birthday, 4th June 1781, all the guns and mortars in Gibraltar were fired in turn, starting from the eastern-most batteries and all firing at the Spanish San Carlos battery. This jubilee discharge was carried out during the Spanish siesta period for greater effect. The Royal Standard was flown from the Grand Battery and received three holes from Spanish shots.

British guns shelling Spanish siege lines on the Isthmus: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

On 9th June 1781, the British gunners hit a major Spanish magazine which exploded. The main explosion was followed by a host of minor explosions, as expense magazines, subsidiary stores and shells blew up. The Spanish lines were in pandemonium as the troops struggled to put out the numbers of fires that started in their camp.

In June 1781, there was increased Spanish naval activity and Eliott arranged the building of two new British gun boats, to increase the defences of the ships at anchor in Gibraltar.

Gibraltar in early 19th Century showing the galleries excavated in the Rock: Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Vilhelm Melbye

Two experimental guns were embedded in the sand near the Old Mole and fired at various elevations with different quantities of powder. In this way, the garrison gunners managed to explode shells over the Spanish camp, to the discomforture of the Spanish troops and the encouragement of the garrison.

The Gibraltar garrison was much concerned over the fate of the British on Minorca, held by a small force of two British and two Hanoverian regiments commanded by General James Murray.

On 20th August 1781, a force of 8,000 Spanish and French troops, commanded by the French Duc de Crillon, landed on Minorca. De Crillon was immediately able to take control of the whole island, less Fort St Philip at Port Mahon, which Murray continued to hold until compelled to surrender by the ravages of scurvy in February 1782. In the end 600 emaciated British and Hanoverian troops appeared from the casemates of Fort St Philip, to the applause of the French and Spanish troops, impressed by their determination and suffering.

Spanish celebrations outside Gibraltar marked their capture of Minorca and correspondingly lowered the spirits of the British garrison.

Map of the British Sortie on 26th November 1781: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

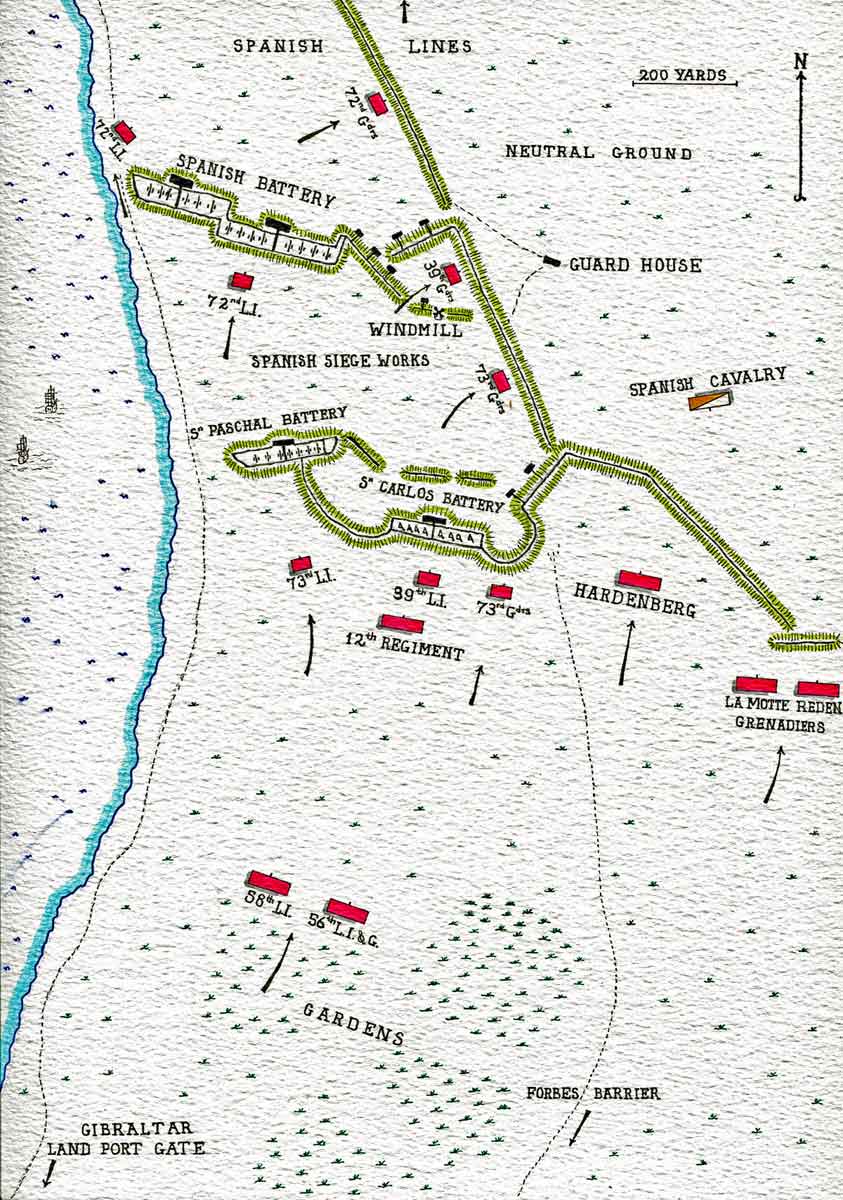

The Siege of Gibraltar; the Sortie:

By October 1781, the Spanish bombardment reached such a pitch and the traverses brought forward so far down the Isthmus, that Eliott was convinced that a general assault on Gibraltar was imminent.

At the end of October 1781, a group of blockade running ships broke through the line of Spanish gunboats and reached Gibraltar, to the jubilation of the garrison.

British officers planning the Sortie on 26th November 1781: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

By the middle of November 1781, the Spanish siege works were nearing the Inundation, an area of water immediately outside the Land Port Gate. Any further advance would enable the Spanish to establish batteries, that would be able to enfilade the whole of the Gibraltar town waterfront and eventually cover the coast at the south-western end of Gibraltar, where for the time being blockade breaking vessels were safe to unload.

on 21st November 1781, Eliott received information from a deserting Spanish Walloon Guard corporal that over 20,000 troops in the Spanish camp were preparing to assault Gibraltar and were only awaiting the arrival of the combined Franco-Spanish Fleet to launch the attack.

Eliott resolved to make a pre-emptive sortie into the Spanish lines.

The British assault was launched on the night of 26th/27th November 1781, after a period of heavy rain, high winds and dark nights. In such weather both sides stayed in their respective shelters.

Light Company Officer of the 73rd Highland Regiment: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

On 26th November 1781, after the firing of the evening gun and the formal closing of the Land Port Gate, orders were issued to the troops for the attack. No early warning was given, for fear notice of the attack would be taken to the Spanish by a deserter, seeking a reward.

The attacking force was commanded by Brigadier William Ross, late lieutenant colonel of the 72nd Royal Manchester Volunteers and comprised the British 12th Regiment, Hardenburg’s Hanoverians and the picked marksmen and flank companies (light and grenadier companies) of the other regiments. Also in the attacking force were parties of artillerymen, artificers and seamen.

Colonel William Picton commanded the supporting troops, comprising the 39th and 58th Regiments.

The various columns moved out at 2am on 27th November 1781, through the gates at the northern end of the Gibraltar settlement and advanced on the Spanish entrenchments and batteries.

General Eliott watches the Sortie on 26th November 1781: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by John Trumbull

The Spanish sentries were alert and fired on the British columns, before escaping to the rear. Other than the artillerymen manning the batteries, there were few Spanish troops in the entrenchments and they were quickly overcome. The guns were all angled to fire up at the batteries on the Rock and could not be brought to bear on the advancing British infantry.

The Spanish did not expect any such sortie by the Gibraltar garrison and were wholly unprepared for it. The gun batteries had been built without the parapet necessary to protect covering infantry and there were no such infantry.

British Sortie on 26th November 1781: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The British infantry columns took positions on the far side of the batteries, while the artillerymen, artificers and seamen destroyed the Spanish works.

The Spanish guns were spiked, the woodwork of the positions set ablaze and powder trails laid to the various magazines.

Map of the British Sortie on 26th November 1781: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

The Spanish guns further to the rear came into action, but directed their fire at Gibraltar town, their usual target, instead of aiming at the British troops destroying their siege lines.

The British batteries opened a heavy covering fire against the Spanish guns, once it was clear where the British infantry and demolition parties were positioned.

British Sortie on 26th November 1781: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by A.C Poggi

General Eliott accompanied the attacking troops and supervised the destruction of the Spanish positions, which had been built with considerable care and skill. To speed the process, Eliott sent back to Gibraltar for the rest of Green’s artificers.

Once the destruction of the Spanish works was complete, the British attacking force withdrew into Gibraltar. As they did so, the Spanish magazines began to explode. The main magazine detonated with an enormous blast, as the last British troops filed in through the Land Port Gate.

The total British and Hanoverian casualties in the Sortie were 2 killed and 25 wounded. Fourteen Months of work by the Spanish and a considerable quantity of ammunition was destroyed.

In addition, the British troops spiked ten 13 inch mortars and eighteen 26 pounder guns in the Spanish siege works, an action which involved driving a large iron spike into the touch hole with a heavy sledge hammer so that the piece could not be fired until the spike had been removed, no easy task.

British Sortie on 26th November 1781: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: a comtemporary illustration

One of the items brought back by the British troops was a report the Spanish officer commanding the siege works was writing at the time of the attack, informing his general that nothing extraordinary had happened that night.

The following night, the Spanish opened a heavy fire on the destroyed positions, in the mistaken belief that the British were occupying them again. They made no effort to re-occupy these positions, which burned for several days.

The morale of the Gibraltar garrison was considerably raised by the successful Sortie, but circumstances in Gibraltar continued to deteriorate, with growing shortages of food and medical supplies.

December 1781 saw strong winds and heavy driving rain that knocked down many of the buildings damaged by Spanish gunfire and swamped the make-shift camps housing the troops and inhabitants in the south of Gibraltar.

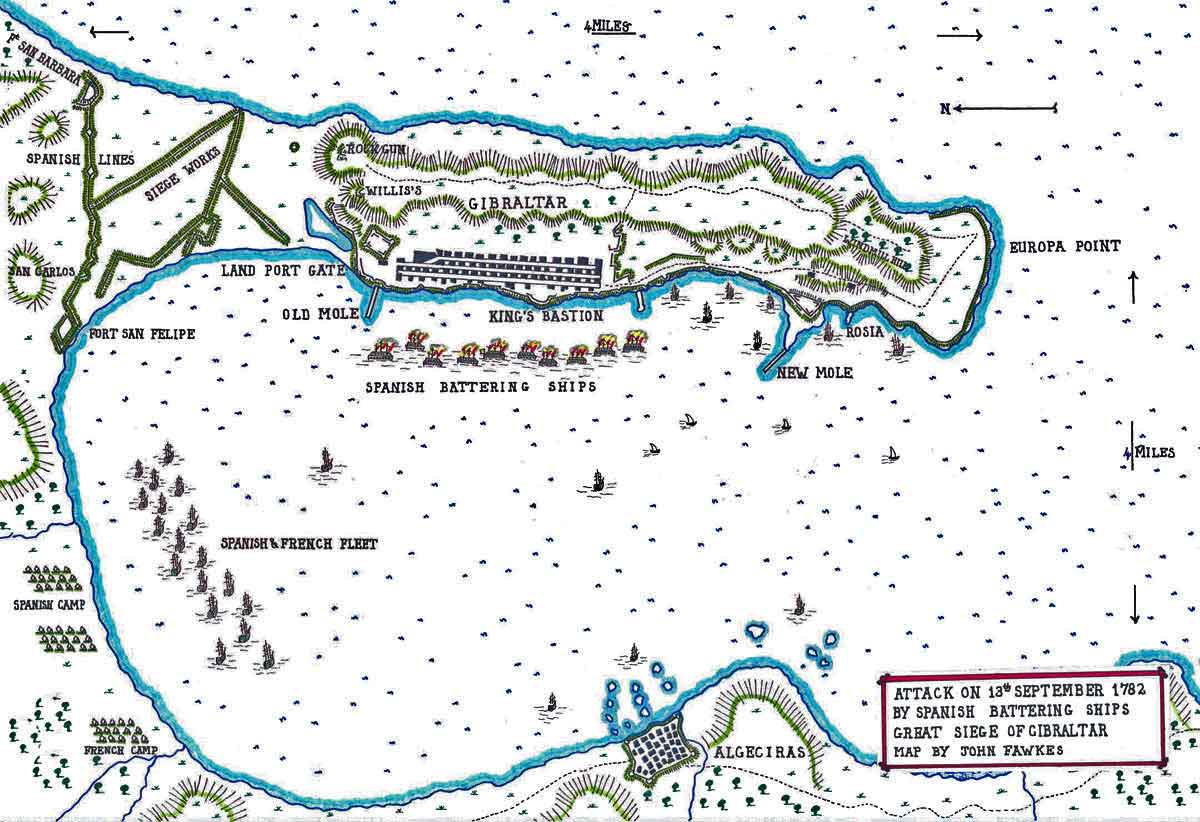

Map of the bombardment from the Spanish Battering Ships on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

The Siege of Gibraltar; the Attack by the Spanish Floating Batteries:

The success of the British sortie from Gibraltar caused great despondency in the Spanish and French ranks. It seemed that Gibraltar could never be captured.

By the end of January 1782, the Spanish rebuilt the siege works destroyed by the sortie. This time the works were well protected with infantry positions and a strong garrison.

General Eliott and his senior officers watching the destruction of the Spanish Battering Ships on 13th September 1782, during the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by George Carter

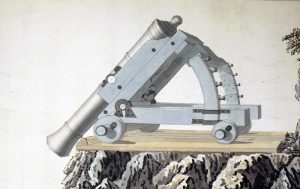

February 1782 saw the introduction of Gibraltar’s new ‘depressing gun-carriage’. Invented by Eliott’s Royal Artillery aide de camp, Lieutenant George Koehler, the gun-carriage enabled a gun to be fired downwards from a position high above its target.

The new carriage was successfully demonstrated to Eliott and other officers on 15th February 1782, the gun landing several rounds in a traverse of the San Carlos battery.

Spanish celebrations and a feu de joie, confirmed by information passed under a flag of truce, revealed that Minorca had finally surrendered on 5th February 1782. Spanish and French resources could now be concentrated on taking Gibraltar.

Attack on Gibraltar, using the Battering Ships and attacking by land on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: a print by Esnauts and Ropilby expressing how the Spanish and French expected the assault on Gibraltar to be executed

The Spanish lines were extended. New guns and mortars were installed in the batteries and old guns replaced. A new cavalry camp was established and roads built from it to the Isthmus.

12. Podcast of The Great Siege of Gibraltar, between 8th July 1779 and 2nd February 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

12. Podcast of The Great Siege of Gibraltar, between 8th July 1779 and 2nd February 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Then further relief arrived by sea from Britain. On 25th February 1782, the ordnance ship St Ann arrived with stores, including the kits for two new gun boats.

On 10th March 1782, the Vernon arrived, carrying ten more gun boats in kit form, with two frigates and four transports carrying drafts of men for the garrison regiments and an additional regiment, the newly raised 97th. The new troops were a sickly lot and it was some time before they were of use to the garrison for duties.

The gunboats were assembled and the first launched on 17th April 1782.

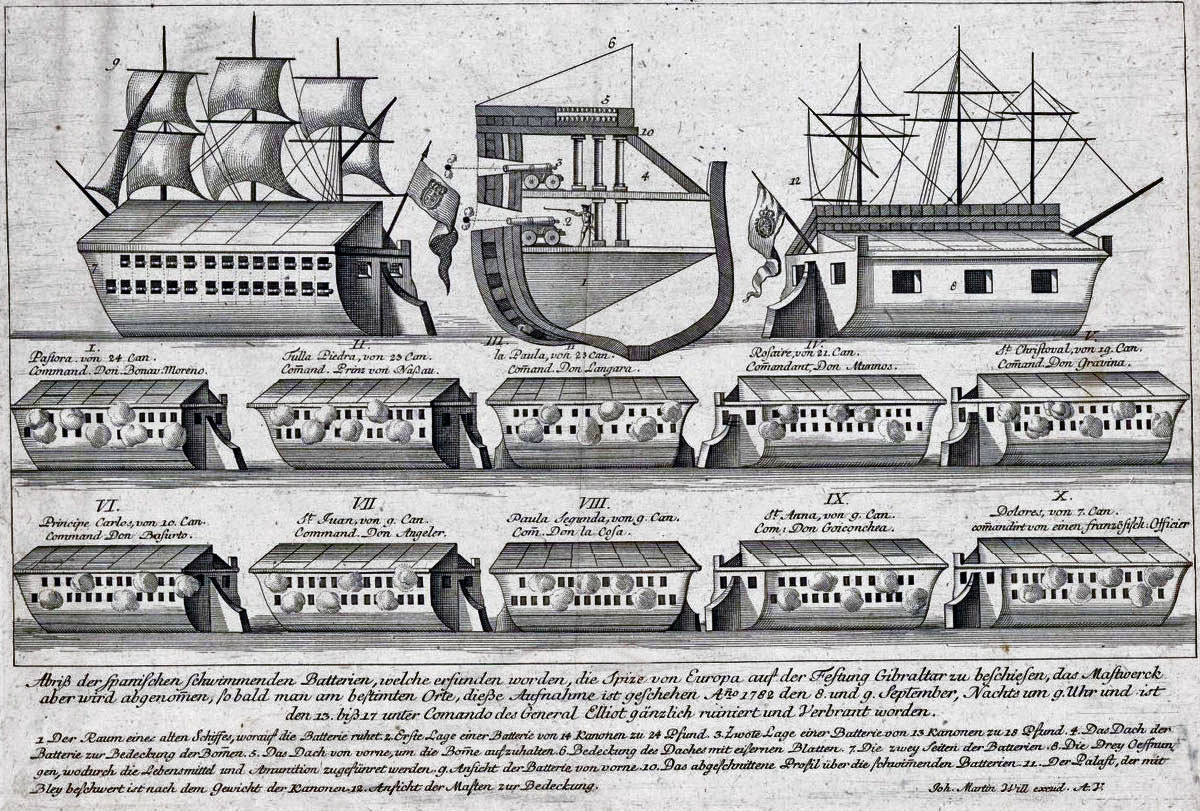

Chart giving details of the Ten Spanish Battering Ships that attacked Gibraltar on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: the chart is misleading in that the ships were different sizes and the guns were, in every ship, on the port side

On 1st April 1782, Eliott wrote in a report to London that a dozen Spanish ships were being prepared in Algeciras as battering-vessels.

Michaud D’Arcon, the French military engineer who supervised the construction of the Ten Spanish Battering Ships: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

A new attack on Gibraltar was under preparation, commanded by the Duc de Crillon, recently arrived from his success on Minorca, with the assistance of an experienced French military engineer, Michaud D’Arcon.

The details of the Spanish plan were soon widely known on Gibraltar.

Warships were assembling in Algeciras, among them several large ships that were to be rebuilt. These were the proposed ‘Battering Ships’.

Transport vessels brought a further 9,000 troops, who landed and encamped in the Spanish lines.

Everywhere the Gibraltar garrison looked on the mainland there was a mass of activity aimed at finally capturing the Rock.

The plan as put to D’Arcon, was for a squadron of battering ships to take on the British land based batteries and beat them down by numbers and weight of shots fired, before a storming party attacked from the siege works on the Isthmus and troops were put ashore from the waiting Spanish fleet.

D’Arcon’s role was to design the battering ships as ‘unsinkable’ and ‘unburnable’.

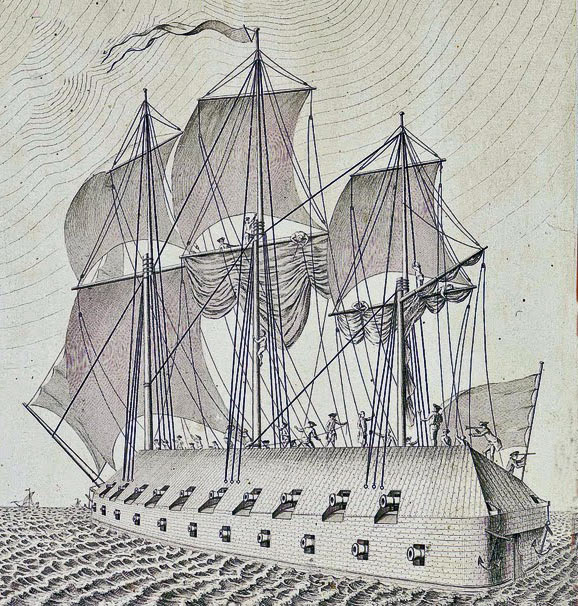

Ten Battering Ships were built. After each ship was cut down on the starboard side and much of the rigging and masts removed, a shot-resistant roof was built over the deck. Guns were to be fired from one side only. The starboard battery was removed completely and the port battery heavily augmented. The port side was strongly reinforced with timber and sand infill.

Pastora, flagship of the squadron of ten Spanish Battering Ships, destroyed with the rest of the squadron in the attack on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

D’Arcon designed and installed an intricate system of hoses to extinguish any fire on board.

While the work on the battering ships was going on, between March and August 1782, the preparation of further siege works ashore was suspended to release the large numbers of workmen required for the ships.

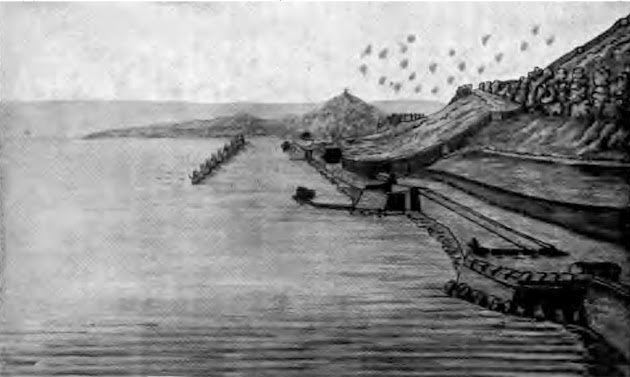

The Spanish ‘Junk Ships’ or Battering Ships advancing on Gibraltar on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: sketch by Captain John Spilsbury, an eyewitness

Eliott’s despatches to London called for a reinforcement of large warships to counter the Floating Battery, but no such reinforcement was forthcoming. Instead, Eliott worked on his own counter weapon, red-hot shot. Grates for the heating of shot were installed in all the Gibraltar batteries.

On 11th June 1782, a Spanish shell exploded in the expense magazine of Princess Anne’s Battery, causing a substantial explosion and killing 19 men. The Spanish turned out, with drums beating and their fire was redoubled, but the Gibraltar garrison also turned out. Nothing further happened and the battery was quickly back in action.

Bombardment from the Spanish Battering Ships on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The Battering Ships came to be known as ‘junk ships’, because they were being cased with heavy rope cables, referred to as ‘junk’, that would be resistant to shot and, when soaked with water, also to fire.

In May 1782, Eliott was inspecting the batteries on the North Face with Colonel Green and their staff, when Eliott said that he would give 1,000 dollars to anyone who came up with an idea for building batteries on the North Face, that could enfilade the Spanish lines. It is said that Sergeant Major Ince of the Artificers proposed the excavating of galleries in the rock.

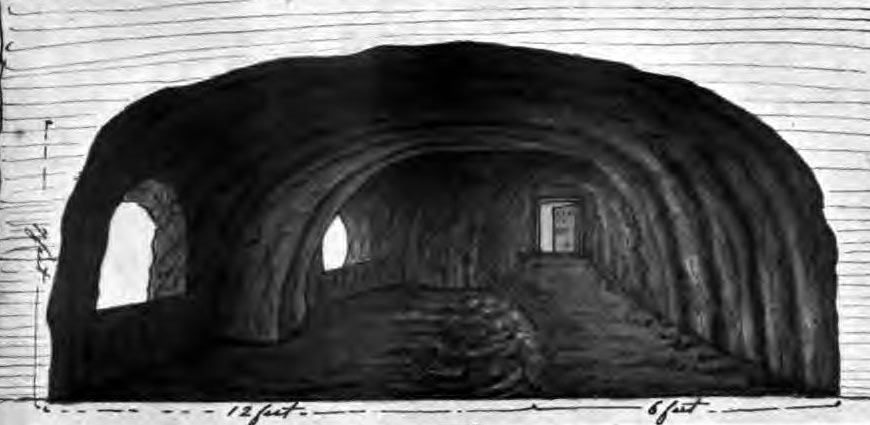

Ince’s Gallery: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: sketch by Captain John Spilsbury

Ince was given the job of carrying out the excavations and, by September 1782, a battery of five 24 pounder guns was in action from a gallery cut through the rock, high up on the North Face. Further batteries were later built. The only way Spanish counter-fire could damage these batteries was by a direct hit on an embrasure. These galleries are now one of Gibraltar’s most notable features.

On 25th July 1782, the vessel St Philip’s Castle arrived in Gibraltar. She brought a party of Corsican exiles, who joined the garrison, and news of Admiral Rodney’s victory over the French fleet at the Battle of the Saints, in the West Indies, on 12th April 1782. Rodney’s victory was celebrated with a parade and feu de joie.

General Eliott with his adc Lieutenant G.F. Koehler in the King’s Battery during the bombardment by the Spanish Battering Ships on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The Spanish pushed ahead with the preparations for the assault. Special landing craft were prepared, with hinged bridges to assist in putting troops ashore, once the defending guns were destroyed by the fire from the heavy guns on the Battering Ships, now strengthened with a seven-foot thickness of timber and other material on their exposed sides.

More men were working on the siege works, progressing down the isthmus towards the North Face.

Spanish Battering Ships that attacked Gibraltar on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: port side on the left and starboard side on the right

On 16th August 1782, the Gibraltar garrison was amazed to find that thousands of Spanish workmen had, during the night, built a 500-yard-long entrenched embrasure across the isthmus. This work was then used as cover for the building of three new batteries.

A Spanish deserter informed the British that the bombardment, intended finally to beat down the British garrison and precede the taking of Gibraltar, was due to start on 25th August 1782.

The Spanish tested two of the Battering Ships in the sea close to Algeciras. The British noted that one of the ships had to be towed by ten gunboats.

Defence of the King’s Bastion against the bombardment from the Spanish Battering Ships on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

Eliott prepared his garrison for the coming attack. Structures in the batteries were strengthened, furnaces for heating red hot shot installed in every battery and the gunners trained in the loading and firing of the shot. The use of red hot shot was pioneered in Gibraltar during the Great Siege and was in due course adopted across Europe.

The troops were placed in their battle stations: the 39th encamped in South Port Ditch, the 73rd in the town, the 12th behind the New Mole, the 72nd in the King’s and Montague’s Batteries. The Corsicans were on Windmill Hill. The 97th, still not fit for full duty, was at Rosia.

Spanish attack on 13th September 1782 using the Battering Ships: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Georg Balthasar Probst: the ten Battering Ships can be seen exploding or smoking in the middle ground

On the Spanish and French side, the Battering Ships were moored in a line outside Algeciras. The siege lines were far from ready, many of the embrasures being blocked by bags of sand.

The British opened a barrage against the advanced siege lines on the Isthmus at 7am on 8th September 1782, using red hot shot for the first time. The fire was devastating, destroying two of the new batteries, with much of the earthworks knocked down. A third battery was set ablaze. Probably around 400 of the French and Spanish troops in the siege works were killed by the British bombardment.

The attack of the Spanish Battering Ships on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Thomas Whitcombe

On 9th September 1782, the Spanish opened a bombardment with all the guns available on and behind the Isthmus. Nine Spanish and French warships joined in the cannonade, sailing in line ahead down the Gibraltar coast, discharging broadsides at the buildings on-shore.

Spanish Battering Ships moving into position on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: engraving by Bergmuller

Despite the activity, a small blockade running vessel ran in to Gibraltar with food.

That night the Spanish gunboats lay off the coast and fired grapeshot into Gibraltar.

The attack was renewed on subsequent days in the same form. Breaches appeared in many important parts of the Gibraltar defences.

The ‘depressing gun carriage’ devised by Lieutenant Koehler, adc to General Eliott: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The rate of Spanish fire rose to 6,500 shot and 2,080 shells every 24 hours.

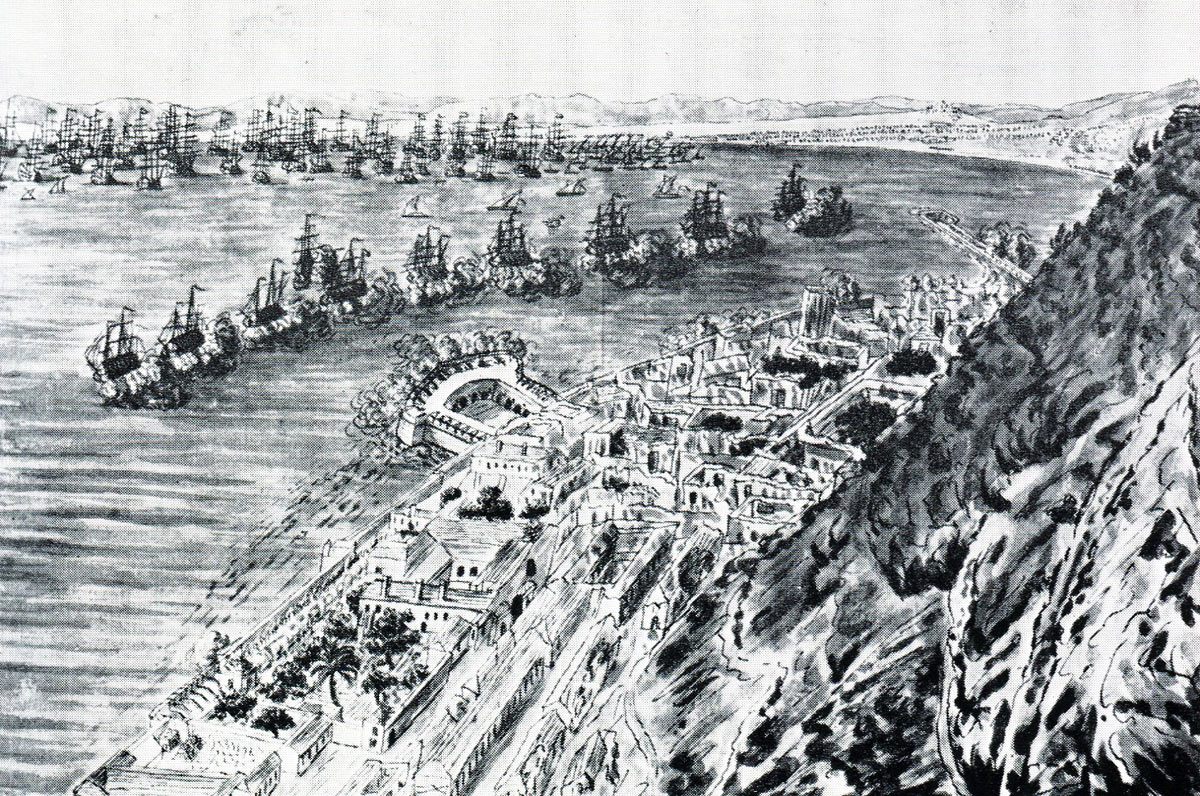

In the days up to the 12th September 1782, more Spanish and French ships arrived in the bay, making a combined fleet of 3 three-deckers, 41 other ships of the line, together with smaller vessels, in all more than 80 ships.

One of the Spanish ships was struck by a red-hot round and the apparent panic this caused was deeply gratifying to the British gunners, leading to strenuous efforts to ensure a wider supply of this devastating weapon.

The core of the Franco-Spanish fleet was the new squadron of ten Battering Ships, varying in size but all heavily protected and armed.

The squadron was commanded by Rear Admiral Bonaventura Moreno, who flew his flag in the largest ship, the Pastora, mounting 21 heavy guns. In all, the squadron carried 142 guns. The essential components of each ship were a very thick layer of wood and other materials on the port side and a sloping roof, re-inforced and containing a reservoir of water, which would keep the ship’s structure thoroughly soaked against combustible projectiles.

Spanish Battering Ships set on fire during the attack on Gibraltar, 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Thomas Davis

The crews of the Battering Ships amounted to 5,260 officers and seamen. The seamen appeared to be pressed men or convicts, as they were escorted to their ships by Spanish cavalry, suggesting they were put aboard under coercion. 36 men were allotted to each gun, to fire in relays, so that a constant fire could be maintained over a period of hours.

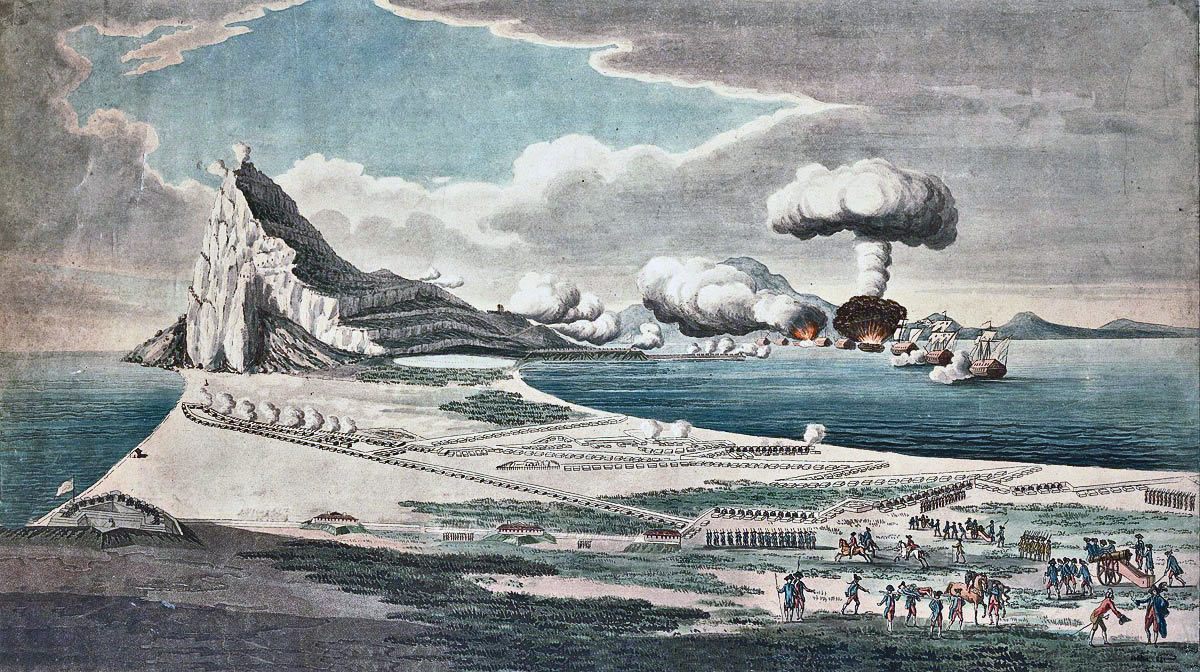

The Spanish attack was launched at 7am on 13th September 1782, with the ten Battering Ships leaving their moorings and lumbering across the bay to their allotted positions for the bombardment, that was expected to bring the British occupation of Gibraltar to an end.

View of the attack by the Spanish Battering Ships on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: the Spanish ship Pastora explodes in the distance

The Battering Ships were in position, 1,000 yards off the Gibraltar coast, by 9.45am; Moreno’s Pastora opposite the centre of the King’s Bastion and the other nine ships in position ahead and astern of Pastora. As they dropped anchor, all the guns on Gibraltar opened fire, to be answered by the Spanish and French guns ashore and the guns of the Battering Ships. The climactic battle of the Great Siege of Gibraltar was under way.

Spanish and French fleet headed by the Ten Battering Ships on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: eye witness sketch by Lieutenant G.F. Koehler

The deployment of the Battering Ships had been widely heralded across Spain and France. In Paris, there was even an opera performed, the central theme being the Siege of Gibraltar, its triumphal capture by the French and Spanish and the decisive role played by the Battering Ships. D’Arcon was a national hero.

Initially, the Battering Ships fired too low and their rounds landed in the sea, short of their target. This was corrected and the heavy guns began to take a terrible toll of Gibraltar’s defences. What remained of the town was reduced to rubble and the sea front walls were severely battered, with whole sections destroyed.

The King’s Bastion was the main target and it suffered badly, but never to the extent that the guns in its embrasures ceased firing.

D’Arcon’s modifications to the Battering Ships initially had the desired effect. Shells exploded without causing damage to the ships and even 32 pounder cannon balls were unable to penetrate the immensely thick ships’ sides.

The Ten Spanish Battering Ships in action on 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: eye witness sketch by Lieutenant G.F. Koehler

It was not until midday that the furnaces in Gibraltar’s batteries were sufficiently hot to produce the ‘red-hot shot’ needed to counter the Battering Ships.

Initially the red-hot shot seemed to make little impression on the Battering Ships. D’Arcon’s system of hoses and soaking wet sacking and rope work appeared to suppress any fires, assisted by the crew equipped with hoses. But red hot shot is an insidious implement. It lodges in the woodwork and smoulders, perhaps for an hour, before causing the material around it to burst into unquenchable fire.

The conventional Spanish naval vessels attempted to join the well anchored Battering Ships in bombarding the Gibraltar shoreline, but a strong south-westerly wind blew up, with a heavy swell and the vessels were unable to approach the coast.

Fires on the Pastora were seen at around 2pm, but were mastered by the crew. By 7pm, the fire from the Battering Ships had fallen away and only a few guns were still firing.

12. Podcast of The Great Siege of Gibraltar, between 8th July 1779 and 2nd February 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

12. Podcast of The Great Siege of Gibraltar, between 8th July 1779 and 2nd February 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

The conditions for the gun crews on the Battering Ships were murderous. The guns had been in action ceaselessly from 9am. The gun decks lacked ventilation and the fumes and heat were overwhelming. The crews were unable to see what was going on beyond the gun ports, feeling only the repeated vibration as cannon balls struck the ships.

The destruction of the Battering Ships during the attack on Gibraltar, 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Thomas Whitcombe

By 9pm, the guns on all the Battering Ships had ceased firing, although there was still a heavy cannonade from the shore. By midnight, most of the Battering Ships were ablaze and the crews were sending up distress rockets. Spanish boats crowded around to rescue the crews and were fired into with grapeshot by the Gibraltar batteries.

The fight around the sinking Spanish Battering Ships on 13th September 1782 : the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: print by William Hamilton and Archibald Robertson

By 1am on 14th September 1782, it was apparent that the Spanish attack had failed and all the Battering Ships were ablaze. Captain Curtis led the British gunboats up to the Battering Ship line and raked with grape shot the Spanish vessels crowded around them, taking off the crews. The rescue was abandoned and the Spanish vessels escaped, leaving Curtis and his gunboat crews to take over the recovery of the remaining Spanish crew.

The destruction of the Battering Ships during the attack on Gibraltar, 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

Curtis’s pinnace was alongside one of the Battering Ships when it finally exploded, killing the men still on board as well as Curtis’s coxswain. Many more, Spanish and British, were injured.

Around 350 Spanish crew were rescued by Curtis’s boats. The Spanish batteries on the mainland continued to fire on the confused mass of burning ships, generating more casualties, mainly among their own countrymen.

Captain Curtis rescuing Spanish crews from the sinking Battering Ships during the attack on Gibraltar, 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

By 4am, all the Battering Ships were sunk, leaving the Gibraltar waterfront a mass of debris and bodies from the wrecked Spanish ships. During the action 40,000 rounds had been fired.

A British sailor found the large ensign flown by the Spanish admiral from the stern of the Battering Ship Pastora, with such high expectations. The sailor took the ensign ashore and presented it to Eliott.

On 14th September 1782, the Spanish army turned out and marched from their various camps to form up behind the batteries at the northern end of the Isthmus. At the same time, the Spanish ships moved across the bay, packed with troops. It looked as if the long-expected invasion of Gibraltar was about to be launched.

The British troops manned the fortifications and the guns redoubled their fire.

Nothing happened. The Duc de Crillon cancelled the assault, forming the view that the outcome must be unsustainable losses for the attacking force.

News of the complete failure of the grand plan to capture Gibraltar, using the Battering Ships and land and sea attack, reached the Spanish and French capitals and was greeted with stunned incredulity.

British sailors rescuing the Spanish crews from the exploding and sinking Battering Ships during the attack on Gibraltar, 13th September 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The Siege of Gibraltar; the Final Relief by Admiral Lord Howe:

Despite the triumph over the Battering Ships, Eliott could not rest on his laurels. The Spanish bombardment from the shore batteries continued through September 1782, while the levels of supplies on the Rock fell.

Eliott wrote to London that his daily expenditure of ammunition was very great (on 13th September 1782, 716 barrels of gun powder and 8,300 rounds were fired from Gibraltar’s guns) and his supplies of food would only last to the end of the year.

The maritime situation was perilous for Britain. There were Spanish and French fleets in the English Channel and a hostile Dutch fleet in the North Sea.

A British convoy of merchantmen was gathering in the Channel for America and India and further ships were added to supply Gibraltar.

Admiral Lord Howe, commander of the Third Gibraltar Relief Fleet: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

The fleet, commanded by Admiral Lord Howe, sailed from Spithead, outside Portsmouth, on 11th September 1782, with 34 ships of the line, several smaller naval vessels and 140 merchant vessels, 31 of which were for Gibraltar, carrying supplies and the 25th and 59th Regiments of Foot.

The French and Spanish fleets were larger than Howe’s, but the Spanish ships were in disrepair, none of them having copper sheathing to their ship’s bottoms, a standard feature of British warships by this time.

A storm dispersed Howe’s fleet, but he gathered it together and, on 8th October 1782, reached Cape St Vincent. A frigate went on ahead and returned with the news that the attack on Gibraltar had been repelled and that the garrison still held out.

A further storm arose, which caused Howe little inconvenience, but, reaching hurricane strength, struck the Spanish and French ships at Algeciras, many of them making ready for sea and without sufficient anchors. Several of these ships were forced onto the rocks and others were blown out to sea. One damaged Spanish two-decker drifted across the bay and was forced ashore below the Gibraltar fortifications, where she surrendered. This ship, the San Miguel, was later repaired and taken into the Royal Navy as HMS St Michael, following the tradition in most navies of keeping the original name of a captured ship.

British troops of the 25th Regiment: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture attributed to Giuseppe Chiesa

Howe’s fleet came in sight of the Gibraltar garrison on 11th October 1782. The fleet formed for battle in three divisions, Howe’s flagship, HMS Victory, leading the third division, while the merchant ships made for Gibraltar. Most of the merchantmen were blown past Europa Point into the Mediterranean, to be gathered up by the Royal Navy and brought back into Gibraltar over the following days. The Spanish ships made no attempt to intervene.

Admiral Lord Howe’s Third Relief Fleet sails into Gibraltar on 11th October 1782: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Richard Paton

The End of the Siege of Gibraltar:

The merchant vessels were unloaded in Gibraltar while Howe’s fleet remained at sea bringing in the ships that had strayed into the Mediterranean.

As with Darby’s relief, the Royal Navy ships provided a substantial store of gun powder to the garrison before leaving.

The Spanish and French warships finally came out to confront Howe on 13th October 1782. The opposing fleets manoeuvred off Gibraltar, but no battle took place. Howe’s responsibility was now complete and he headed for England.

British troops standing in the King’s Battery on the Gibraltar waterfront: Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

On 20th October 1782, the two fleets met briefly before Howe sailed on.

With his fresh supplies of ammunition, Eliott renewed the bombardment of the Spanish siege lines with enthusiasm.

Despite his assurance to the Spanish King that Gibraltar would still be taken, it seemed that Crillon accepted that there was now little chance of this happening.

The French troops all left the besiegers’ encampments and the number of Spanish troops was steadily reduced.

Crillon began a search for a mine shaft that was reputed to have been begun under the British lines in the 1727 Siege.

The Spanish troop numbers fell to 15,000 and the Spanish and French fleets dispersed, leaving one ship of the line. The Spanish bombardment fell to 150 rounds a day.

On Gibraltar, the damage caused during the Spanish attack was repaired and Ince’s Gallery in the Rock was extended to 100 yards and another similar tunnel built with embrasures for guns.

Tunnels built in the Rock: the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

By the end of 1782, negotiations for a general peace were under way in Paris. In January 1783, a treaty was agreed between Britain and Spain. Minorca, Florida and some West Indies Islands went to Spain, while Gibraltar remained British. The Siege was over.

The firing in Gibraltar ended on 2nd February 1783. The Duc de Crillon visited the Rock and was shown around, expressing considerable amazement at the system of tunnels bored into the rock, with the batteries they contained.

Casualties at the Siege of Gibraltar:

During the fighting, the British garrison of Gibraltar lost 338 men killed or died of wounds, 536 died of disease, 138 disabled by wounds, 181 discharged from incurable complaints, 872 wounded or diseased who recovered and 43 who deserted.

Spanish and French casualties are not known.

Ammunition expended during the Siege of Gibraltar:

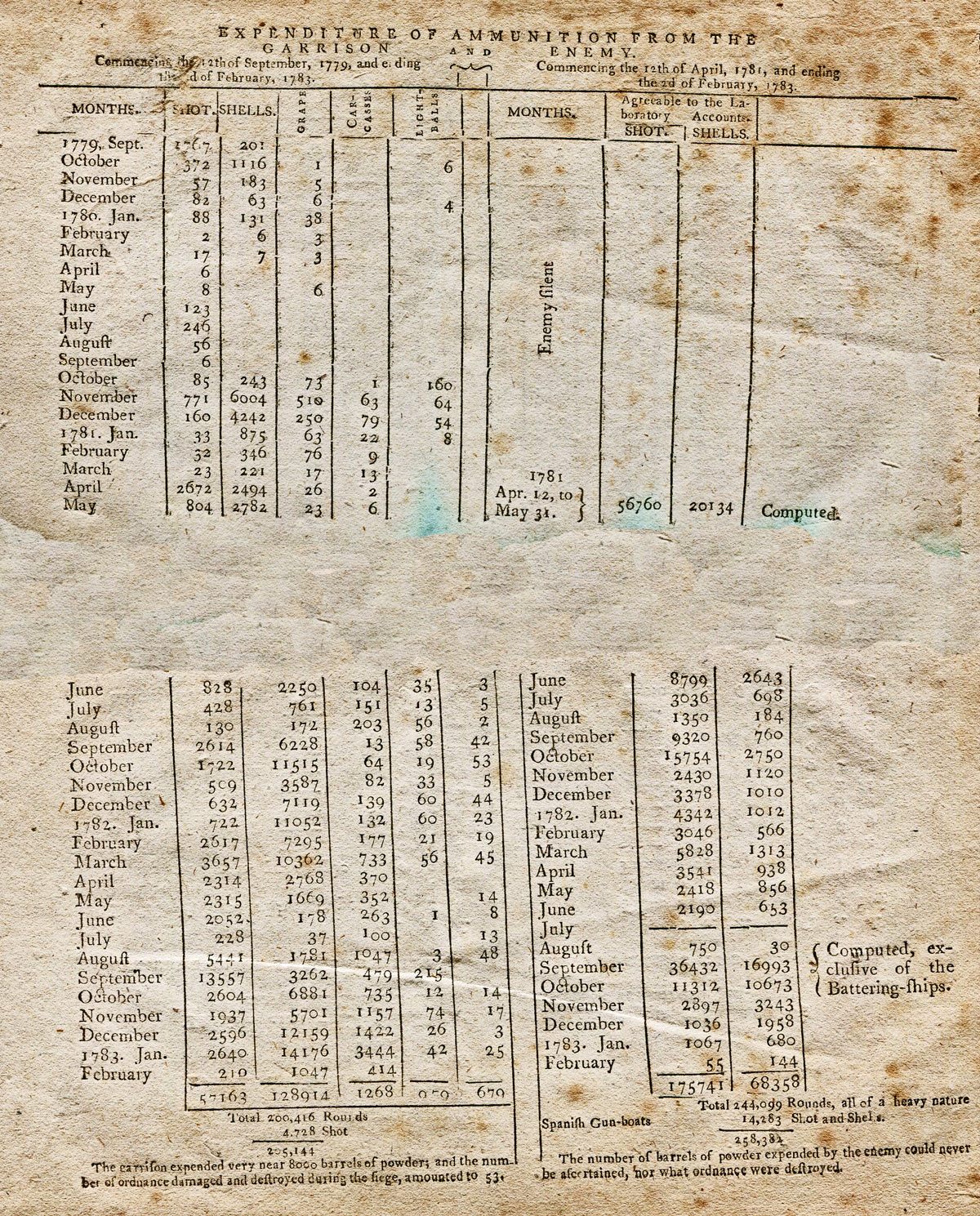

Drinkwater’s book contains a chart setting out the expenditure of ammunition in great detail.

Drinkwater’s chart of cannon ammunition expended by both sides during the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

Follow-up to the Siege of Gibraltar:

Official confirmation of the end of the War and the Siege came with dispatches brought by HM Frigate Thetis on 10th March 1783.

The end of the Siege was marked with parades and gun salutes on Gibraltar.

Both Houses of Parliament passed resolutions thanking General Eliott for his successful defence of Gibraltar and awarded him an annual pension of £1,500 a year.

Medal struck in London by Lewis Pingo commemorating the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: The head is of the governor, George Eliott, Lord Heathfield

Eliott was conferred with the Order of the Bath by King George III. The actual presentation was carried out by the deputy governor, Lieutenant General Boyd, acting on the King’s behalf, at a ceremony in Gibraltar, held on St George’s Day, 23rd April 1783, with a 21-gun salute.

In 1787, Eliott was elevated to the peerage as Lord Heathfield.

Medal struck in London by Droz commemorating the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War: The head is of the governor, George Eliott, Lord Heathfield

Medal struck in Gibraltar commemorating the use of ‘Red Hot Shot’ in the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War

Medals issued to commemorate the Siege of Gibraltar:

The Siege of Gibraltar took place before the institution of campaign medals for British regiments. A number of medals were issued by private initiative to commemorate the Siege in London and in Gibraltar. Several medals specifically honoured the part played by the governor, George Eliott, Lord Heathfield. One medal commemorated the part played by Hanoverian officers of the garrison. Another medal, struck in Gibraltar, commemorated the use of ‘Red Hot Shot’ in repelling the final attack by the Spanish and French.

Medal struck for the senior Hanoverian officers in the garrison at the Great Siege of Gibraltar from 1779 to 1783 during the American Revolutionary War