The siege and capture of Charleston, capital of South Carolina, by the British on 12th May 1780

British siege works on the Neck during the siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: Charleston lies in the distance; the American defensive line on the Neck is marked by the gun shots: the American ships lie in the mouth of the Cooper River in the middle left with the British ships in the background and in the entrance to the Ashley River on the right

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Siege of Savannah

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Camden

To the American Revolutionary War index

Battle: Siege of Charleston

War: American Revolution

Date of the Siege of Charleston: April and May 1780

Place of the Siege of Charleston: City of Charleston, South Carolina, in the United States of America.

Waterfront of the City of Charleston: Siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War

Combatants at the Siege of Charleston: British regulars and loyalist volunteers against American Continental Army and militia regiments.

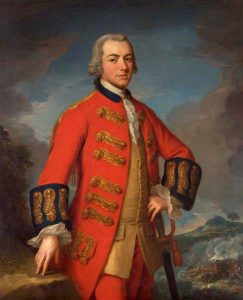

Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton: Siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Andrea Soldi

Commanders at the Siege of Charleston: Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton with Major General Lord Cornwallis as his deputy commanded the British army.

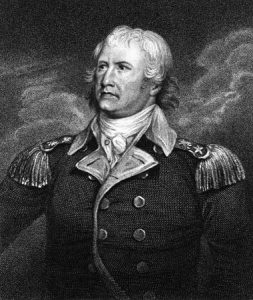

Major General Benjamin Lincoln commanded the American Southern Army and garrison in Charleston.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Siege of Charleston:

The British wore red coats, with bearskin caps for the grenadiers, tricorne hats for the battalion companies and caps for the light infantry.

The loyalist American regiments wore a variety of uniforms, although many wore red coats.

The Americans dressed as best they could. Increasingly as the war progressed infantry regiments of the Continental Army mostly took to wearing blue or brown uniform coats. The American militia continued in rough clothing.

Major General Benjamin Lincoln: Siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War

Both sides were armed with muskets. The British and French infantry carried bayonets. The American Continental infantry were supplied with bayonets, while the American militia were not. Many of the American troops on both sides carried rifled muskets. Both sides were supported by artillery.

Winner of the Siege of Charleston: The British captured Charleston on 12th May 1780.

British Capture of Charleston:

Following the failure of the Americans and French to capture Savannah on 9th October 1779 and the subsequent withdrawal of Admiral D’Estaing and the French fleet and army from Georgia to the West Indies, the British commander-in-chief in New York, Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton resolved to launch a campaign in the southern colonies, in the hope that the loyalist sections of the population would join his army and provide him with the reinforcements needed to mount an invasion of Virginia from the south.

Clinton, with Cornwallis as his second in command, sailed from New York on 26th December 1779 for Charleston. He took eight British regiments, five Hessian regiments, five corps of loyalist troops with artillery and cavalry, all amounting to 8,500 men.

British Light Infantryman and Grenadier: Siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Charles M. Lefferts

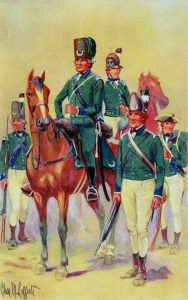

The British regiments were: 1 battalion of Light Infantry drawn from the regiments, 2 battalions of Grenadiers drawn from the regiments, 7th Regiment, 23rd Royal Welch Fusilier, 33rd Regiment, 42nd Regiment, 63rd Regiment, 64th Regiment and the Queen’s Rangers.

The army was conveyed by a fleet of ninety transports escorted by fourteen Royal Navy ships, five ships of the line and nine frigates.

British Grenadier Officer of 63rd Regiment: Siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War

December-January was a hazardous time of year for the weather and the fleet was caught by heavy gales off Cape Hatteras, amounting possibly to a typhoon. Most of the army’s horses were killed in the storms and the ships dispersed. A ship carrying Hessian troops was carried across the Atlantic and went ashore on the Cornish coast in the south-west of England. A ship carrying heavy guns was sunk and several more were taken by American privateers.

The British fleet began re-assembling off Tybee Island in the entrance to the Savannah River at the end of January 1780, and sailed for Charleston on 10th February, arriving off John’s Island in the Edisto River the next day.

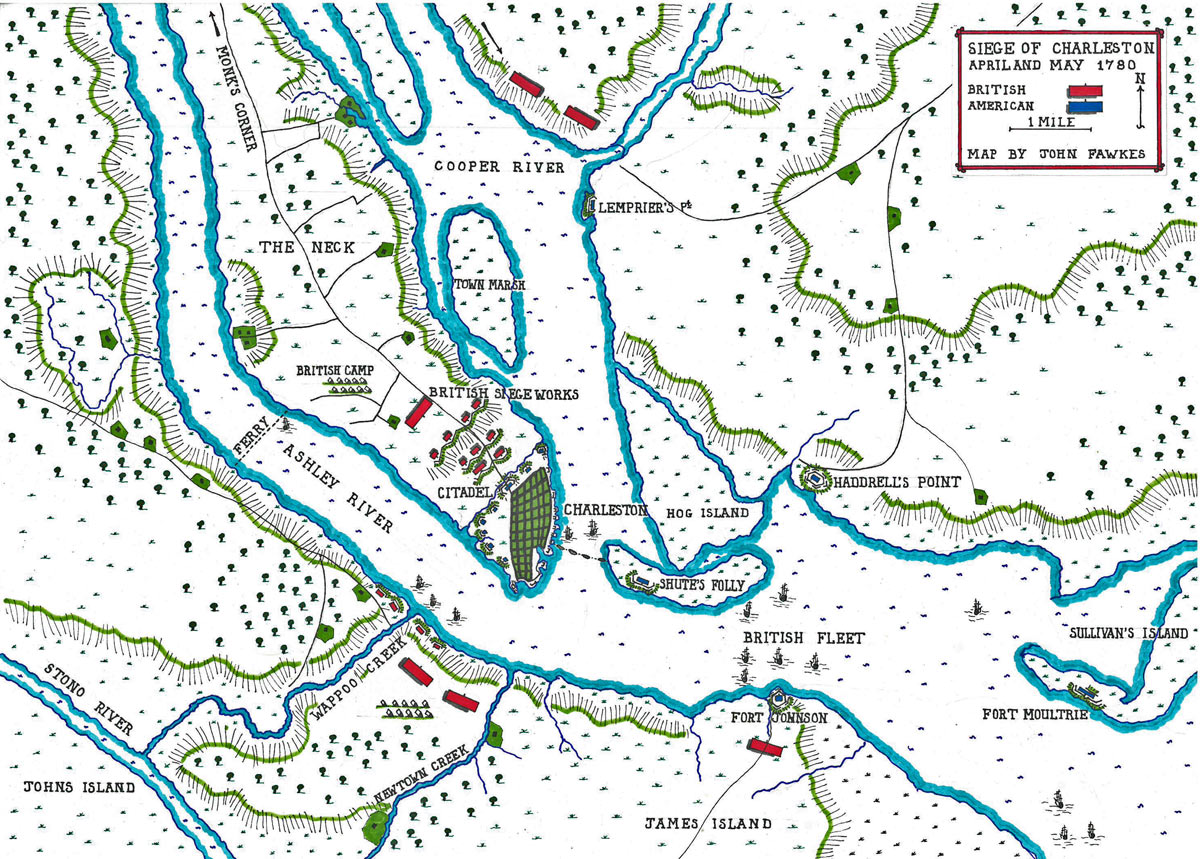

The entrance to Charleston Harbour was defended on the north side by Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island and on the south side by Fort Johnson on James Island. In 1776, the American 2nd South Carolina Continentals and a force of artillerymen repelled an attack on Sullivan’s Island by the British Royal Navy squadron of Commodore Sir Peter Parker.

Since that time, the forts on each side of the estuary had been allowed to fall into a state of disrepair and were no longer garrisoned.

Queen’s Rangers: Siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Charles M. Lefferts

The city of Charleston lies on an isthmus, connected to the mainland by the ‘Neck’. Charleston is bounded on the west side by the Ashley River and on the east side by the Cooper River. The two rivers meet in the estuary at the southern end of Charleston. Inadequate defences had been constructed across the Neck.

Clinton landed troops on John’s Island and his fleet moved into the Ashley Estuary to blockade Charleston Harbour.

Clinton’s troops crossed onto James Island and, on 7th March 1780, crossed Wappoo Creek and began to erect batteries on the west bank of the Ashley River opposite Charleston.

During the month it had taken Clinton to advance, the Americans, under the direction of Governor Routledge, had worked frantically to build up the defences of the city, using a workforce of 600 slaves drafted from the neighbouring plantations.

The Americans dug a flooded ditch across the Neck, backed by a double abatis and a strong breastwork, supported by redoubts. The main redoubt was a stone horn-work, set in the centre of the line where the road passed up the Neck, and named the ‘Citadel’. Sixty-six guns were positioned along the line.

At the southern end of Charleston, facing out to sea, a redoubt was built holding sixteen guns. Along the Ashley River bank, six small redoubts were built, each mounting four to nine guns. Along the Cooper River, seven redoubts were built, each holding three to seven guns. In the estuary, Forts Johnson and Moultrie were repaired and re-armed.

American Continental Frigate Boston: Siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Rod Claudius

A fleet of American ships defended Charleston Harbour, commanded by Commodore Whipple: Bricole (44 guns), Providence (32 guns), Boston (32 guns), Queen of France (28 guns), Aventure (26 guns), Truite (26 guns), Ranger (20 guns), General Lincoln (20 guns) and Notre Dame (16 guns). Several of these ships were purchased from Admiral D’Estaing before the French withdrew from Savannah.

American Regiments at the Siege of Charleston:

In view of the increasing strength of Charleston’s defences, General Lincoln felt confident enough to draw into the city a significant number of the American troops available in the southern colonies.

The initial garrison of Charleston comprised General Lincoln’s force: 1st, 2nd and 5th South Carolina Continentals (800 men), Virginia Continentals (400 men), Horry’s Dragoons, Pulaski’s Legion (380 men) and the North and South Carolina Militia comprising some 2,000 men.

General George Washington sent to the south his 700 North Carolina Continentals under General James Hogun. They arrived at Charleston on 3rd March 1780, after an arduous march. General William Woodford arrived on 6th April 1780 with 750 Virginian Continentals.

3rd North Carolina Continental Regiment: Siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Charles M. Lefferts

Governor Routledge summoned the South Carolina militia for the garrison of Charleston, but they failed to meet the summons, claiming that there was a danger of small pox in Charleston.

Governor Routledge also wrote to the Spanish authorities in Havana on Cuba, requesting the assistance of a Spanish Fleet and Army. The Spanish declined to assist.

British troops at the Siege of Charleston:

General Clinton left 2,500 troops at Savannah and arrived off Charleston with 6,000.

Clinton then sent transports back to New York to bring additional troops, and called on the Savannah garrison to join him.

In mid-March 1780, General Patterson marched in from Savannah with the 71st Highlanders, the light infantry and several loyalist regiments: including Tarleton’s legion infantry, Ferguson’s volunteers, Turnbull’s New York Volunteers, Innes’s South Carolina Royalists and Hamilton’s North Carolina Royalists.

In mid-April 1780, the British officer, Lord Rawdon, arrived from New York with a further 2,500 men.

In addition, there were 5,000 British seamen available from the fleet.

Map of the Siege of Charleston; April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Siege of Charleston:

As part of the disposition of his American army, General Lincoln despatched General Isaac Huger with the American mounted troops, some 500 men from various regiments, to Monk’s Corner, 30 miles upstream from Charleston on the Cooper River, to keep the route out of Charleston to the north open.

Huger’s detachment left Lincoln with around 2,650 continental troops and 2,500 militia, with a circuit of some three miles of fortifications to defend.

Towards the end of March 1780, the British warships began to move up the estuary towards Charleston. The American squadron moved into the mouth of the Cooper River and several warships and civilian ships were sunk across the entrance to the river, and roped together to form a boom from Charleston across to Shute’s Folly Island. The rest of the American squadron took station upstream of the boom. The guns were removed from the American warships to augment the land defences.

On 29th March 1780, Clinton’s British troops crossed the Ashley River from the south bank onto the Neck and began to establish a regular siege of Charleston, ‘breaking ground’ about a mile from the American fortifications and beginning the approach of parallel trenches.

On 8th April 1780, the British ships sailed up past Fort Moutrie and anchored in the estuary between James Island and Charleston. Guns were landed for the British batteries being established on the Neck.

By 10th April 1780, the British batteries on the Neck were ready to open fire on Charleston. General Clinton called on General Lincoln to surrender, which he refused to do.

On 13th April 1780, the British guns opened fire from the batteries on the Neck and on James Island, using heated shot. The firing continued until midnight, setting parts of the town ablaze.

The next day, General Lincoln summoned a council of his senior officers. Lincoln stated that he considered the situation to be desperate and was considering abandoning the town. General Lachlan McIntosh urged that the troops leave Charleston and be transported to the east side of the Cooper River, but Lincoln refused to make a final decision on whether to leave.

In the meantime, the British cavalry, commanded by Colonel Banastre Tarleton, was moving against the Americans at Monk’s Corner.

The British horses had been lost in the storms off Cape Hatteras, but Tarleton replaced his mounts with country horses. On 14th April 1780, Tarleton surprised the American cavalry in camp at Monk’s Corner with an attack at 3am. The American force was destroyed, those not becoming casualties being dispersed. Tarleton captured sufficient dragoon horses for his men to be properly mounted, together with waggons and supplies.

Lieutenant Colonel Webster with the 33rd and 64th British infantry regiments joined Tarleton, and the British force moved south down the east bank of the Cooper River to within six miles of Charleston, cutting off the American escape route across the river.

By 19th April 1780, the British trenches had advanced to within 250 yards of the American line on the Neck.

Lincoln called a further council of war, attended by Lieutenant-Governor Gadsden. Lincoln proposed the alternatives of abandoning the town and retreating or capitulating on terms. Gadsden objected strongly to either proposal, threatening that the townspeople would turn on the American troops. Lincoln gave way in the council, but took matters into his own hands by proposing terms for a capitulation to the British. The terms, which permitted the American troops to leave Charleston, were rejected by Clinton.

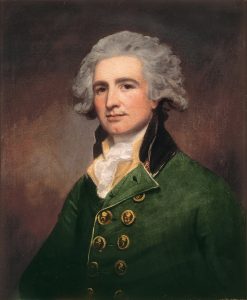

Colonel Robert Arbuthnot: Siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by George Romney

Further fighting took place during the next night, with an American raid on the British siege lines, the British capturing a redoubt on Haddrell’s Point and Colonel Arbuthnot taking Fort Moultrie, whose garrison surrendered without a fight, in sharp contrast to the defence put up by their predecessors on 28th June 1776.

On 8th May 1780, the British trenches were near to the American line on the Neck and the flooded ditch that fronted the American position was drained by a sap cut into the bank.

Prior to an all-out assault, the British again summoned the American garrison to surrender. This time there was no alternative. The Americans could no longer escape from Charleston. British troops occupied the east bank of the Cooper River, the Neck and the opposing bank of the Ashley River. British Royal Navy ships held the estuary.

Lincoln asked for an extension to consult his officers on the issue of surrender, and was given to 9th May. Lincoln demanded terms whereby the American militia would be released and the American continental troops be permitted to surrender with the honours of war. The British rejected this proposal.

The following night was spent by each side bombarding the other with every gun at their disposal. The only tangible result of this display was that the Charleston residents were so cowed that they petitioned Lincoln to surrender.

Lincoln accepted Cornwallis’s terms. The American militia would surrender their arms and be permitted to return home on an undertaking to take no further part in the war. The American continental troops would become prisoners of war.

On 12th May 1780, the American continental troops marched out, their drums beating a Turkish march (this was a compromise on the earlier American demand that they march out playing a British or American march), piled their arms by the town Citadel and became prisoners. The militia followed, handed over their firearms and were eventually permitted to return to their homes, undertaking not to serve against the British Crown again.

Casualties at the Siege of Charleston:

During the fighting, the British lost 76 men killed and 189 wounded.

American losses during the fighting were 89 Continentals killed and 138 wounded. Very few American militia became casualties.

In the surrender, 5,466 American troops became prisoners. The British took 5,916 muskets, 391 cannon, 15 regimental colours, 33,000 ammunition cartridges and 8,000 cannon shot. They also captured the Charleston magazine containing some 10,000 lbs of gunpowder, several ships and other stores.

The explosion of the armoury in Charleston on 14th May 1780: Siege of Charleston April and May 1780 in the American Revolutionary War

Follow-up to the Siege of Charleston:

Following the American surrender, an accident occurred in Charleston on 14th May 1780, in which the armoury being used to store the weapons taken from the American troops exploded.

It is estimated that some 100 people were killed in the explosion and subsequent fire, in which loaded muskets handed in by American militiamen continued to discharge. The neighbouring buildings, a gaol, a barrack and a house of correction were destroyed, and most of the inmates killed.

It was feared that the main magazine, with its substantial store of gun powder, would catch fire and explode, but this did not happen, and the fire was put out by soldiers of both sides, residents of Charleston and the group of slaves drafted into Charleston from the neighbouring plantations by the Americans to construct the defences.

Following the capture of Charleston, the British advanced through the rest of the colony of South Carolina in what became a ferocious civil war.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Siege of Charleston:

- The American General Moultrie, a British prisoner following the surrender of Charleston on 12th May 1780, commented that three times as many American militiamen presented themselves to the British, to surrender their weapons and be allowed to go home, as ever presented themselves for duty during the defence of Charleston.

References for the Siege of Charleston:

History of the British Army by Sir John Fortescue

The War of the Revolution by Christopher Ward

The American Revolution by Brendan Morrissey

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Siege of Savannah

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Camden

To the American Revolutionary War index