The humiliating American abandonment of Fort Ticonderoga on 6th July 1777 to General Burgoyne’s British army

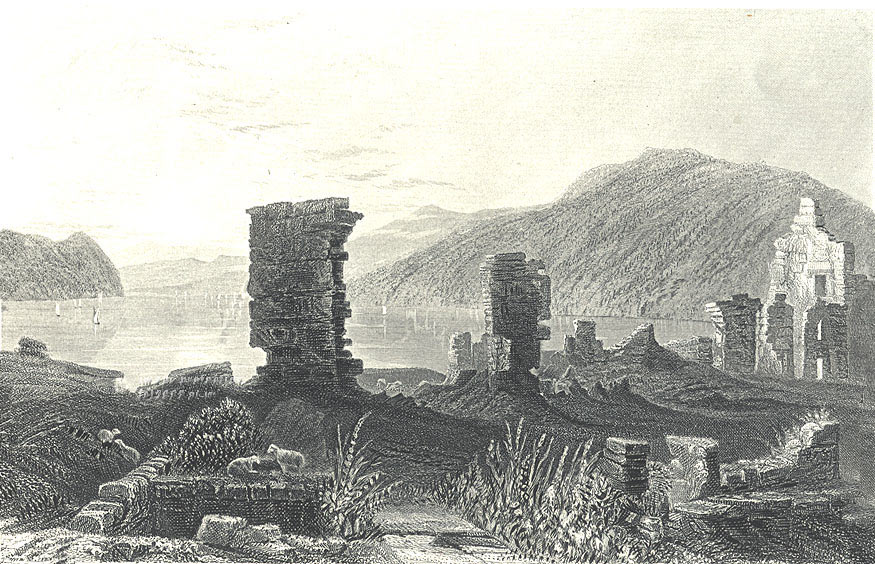

Ruins of Fort Ticonderoga overlooking Lake Champlain: Battle of Fort Ticonderoga on 6th July 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Princeton

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Hubbardton

To the American Revolutionary War index

Battle: Ticonderoga 1777

War: American Revolutionary War

Date of the Battle of Ticonderoga: 6th July 1777.

Place of the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777: Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain, New York State in the United States of America.

Combatants at the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777: British, Hessians and Brunswickers against the American Colonists.

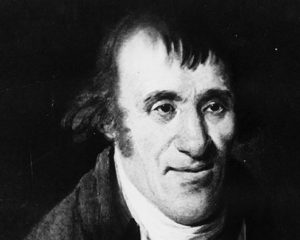

Major-General Arthur St. Clair: Battle of Fort Ticonderoga on 6th July 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Charles Willson Peale

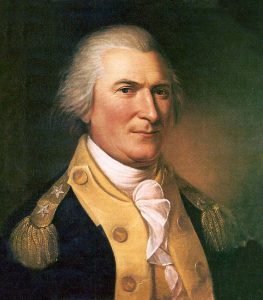

Generals at the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777: Major General John Burgoyne commanded the British and Major General Arthur St Clair commanded the American troops.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777:

7,213 regular British, Hessian and Brunswick troops, a varying but large contingent of Native Americans and 150 Canadians against some 3,000 American troops.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777: The British wore red coats, with bearskin caps for the grenadiers, tricorne hats for the battalion companies and caps for the light infantry.

The German infantry wore blue coats and retained the Prussian style grenadier mitre cap with brass front plate.

The Americans dressed as best they could. Increasingly as the war progressed regular infantry regiments of the Continental Army wore blue uniform coats, but the militia continued in rough clothing.

Both sides were armed with muskets, bayonets and cannon, mostly of small calibre. The Pennsylvania regiments and other men of the woods carried long, small calibre, rifled weapons.

Winner of the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777: The Americans withdrew precipitately from Ticonderoga leaving it in British hands.

British Regiments at the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777:

9th, 20th, 21st, 24th, 47th, 53rd and 62nd Foot, King’s Loyal Americans and Queen’s Loyal Rangers.

German regiments at the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777:

Prinz Ludwig Dragoons

Specht’s Regiment.

Von Rhetz’s Regiment.

Von Riedesel’s Regiment.

Prinz Frederich’s Regiment.

Erbprinz Regiment.

Breyman’s Jaegers.

American Regiments at the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777:

Francis’ Massachusetts Regiment.

Marshall’s Massachusetts Regiment.

Hale’s New Hampshire Continentals.

Cilley’s New Hampshire Continentals.

Scammell’s New Hampshire Continentals.

Several other undermanned corps.

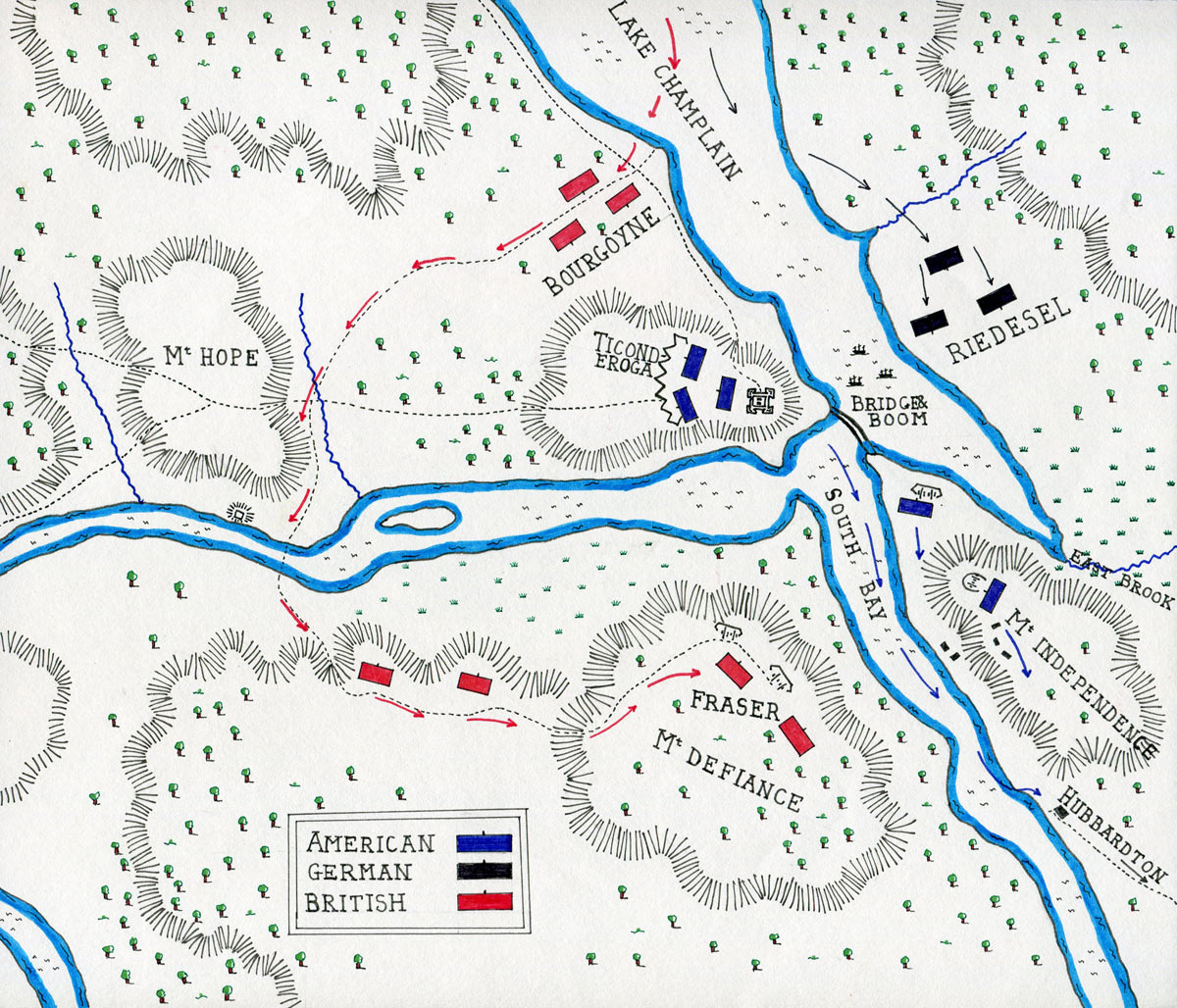

Map of the Battle of Fort Ticonderoga on 6th July 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777:

Fort Ticonderoga was built by the French as Fort Carillon, when they held Canada and the routes to the southern end of Lake Champlain. In 1758 during the French and Indian War, the fort was the scene of the Battle of Ticonderoga between the British and American colonists and the French under the Marquis de Montcalm. The following year, the fort was captured by the British under General Amherst.

Ethan Allen, Benedict Arnold and the ‘Green Mountain Boys’ surprising the British garrison of Fort Ticonderoga in 1775

With the Treaty of Paris in 1763 and the end of the French and Indian War (the Seven Years War), all of Canada passed to the British and Fort Ticonderoga lost its previous strategic significance. That is until the American Revolutionary War broke out. By that time the stone fortifications had fallen into ruin and the garrison comprised 70 British pensioners.

In 1775, Fort Ticonderoga was surprised and captured by the Americans under Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold. The Fort provided the heavy artillery that the colonists needed to bombard General Gage out of Boston. Ticonderoga again became an important bastion on the route from the Hudson River to Canada, this time to resist British invasion from north to south.

The end of the 1776 campaigning season saw the British force under the governor of Canada, Guy Carleton, and Major General “Gentleman Johnnie” Burgoyne, advancing south down Lake Champlain.

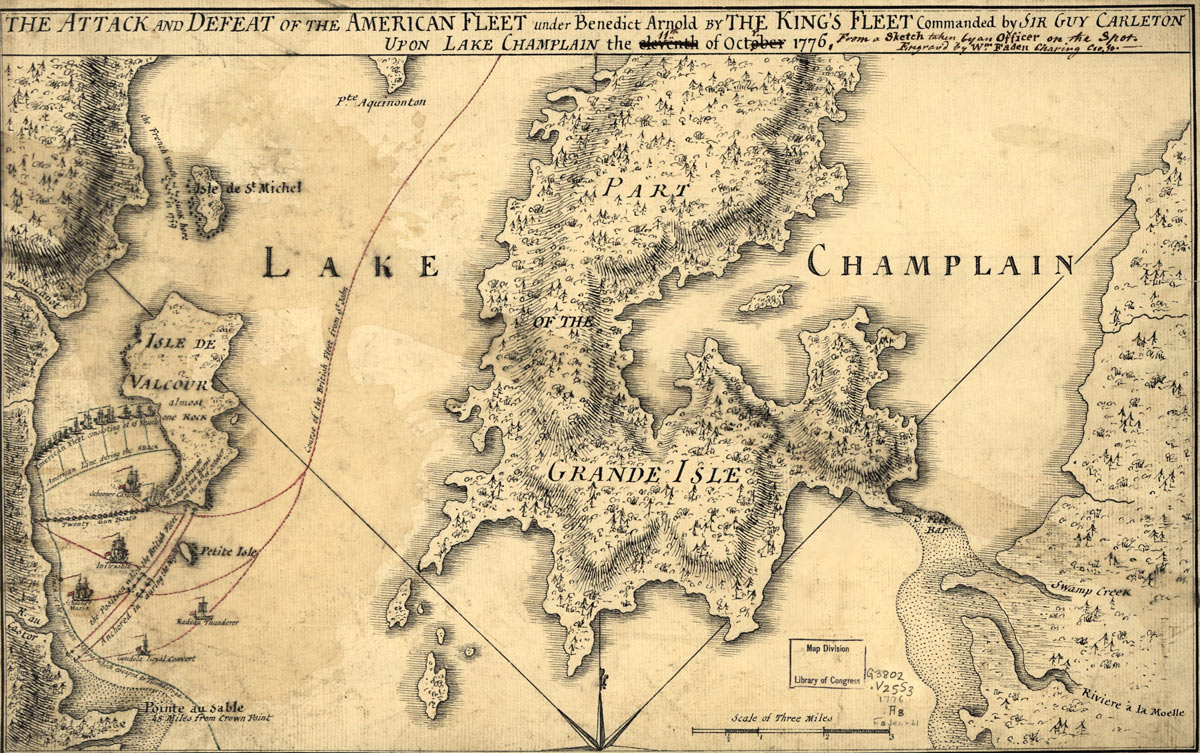

Battle of Valcour Island: The British advance was delayed by the presence on Lake Champlain of an American fleet, commanded by Benedict Arnold. Between 11th and 13th October 1776, Governor Carleton’s ships fought the successful Battle of Valcour Island against the American ships. Eleven of the nineteen American vessels were destroyed.

The British now threatened Fort Ticonderoga. But the year was far advanced and Carleton was an old North American hand. He considered it would be too difficult to supply a garrison in Ticonderoga over the winter, by a long route that would be snowed up with the waterways frozen, and withdrew his forces to Canada, in the face of considerable objection from Burgoyne and others who wanted to seize the fort that year.

Over the winter, Lord Germaine, the Secretary of State for the Northern Department, the minister with the direction of the American War, persuaded King George III to appoint General Burgoyne commander of the expedition planned to attack the American colonies by way of the Lake Champlain route during 1777. Carleton was superceded, losing to the British war effort an officer of judgement and experience.

On 20th June 1777, the British invasion force assembled in the St Lawrence River to begin its advance south.

Over the winter of 1776/7, Major General Arthur St Clair, the officer appointed by Congress to command at Ticonderoga, and his garrison strove to bring the fort to a proper state of defence. St Clair and his men faced considerable difficulties. Ticonderoga, originally Fort Carillon, had been built by the French to keep the British at bay and consequently faced south, the wrong direction to resist the British incursion. With the end of the French and Indian War, Ticonderoga had lost its purpose and been allowed to fall into disrepair.

In the summer of 1776, an American officer, Lieutenant Colonel John Trumbull, prepared a report on the defences of Ticonderoga. Trumbull recommended that the axis of defence be moved from the existing fort to a mountain on the opposite side of the lake, then known locally as Mount Rattlesnake. The recommendation was accepted and, in keeping with the spirit of the times, Mount Rattlesnake became Mount Independence. Unfortunately, Trumbull’s further recommendation, that a prominence called Sugar Hill which overlooked the whole area also be fortified, was ignored. It seemed sufficient to change its name to Mount Defiance.

British and Native Americans: Battle of Fort Ticonderoga on 6th July 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Charles Henry Granger

St Clair’s engineering officer, Colonel Jeduthan Baldwin, worked tirelessly in the face of shortages and disease to prepare Ticonderoga for attack by the British. By July 1777, Baldwin had built batteries, stockades and block houses and, to link the old Fort Ticonderoga with the fortifications on Mount Independence, a bridge and boom.

On Mount Independence, the Polish military engineer, Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko, built batteries and fortifications. Kosciuszko again advised the fortification of Sugar Hill, but the work was not done. There were probably too few American troops to carry out the additional work on Sugar Hill.

The spirit of the American garrison was good. There were too few of them, but they were ready to fight. Parties of New England militia came to the encampment, stayed long enough to deplete the garrison’s stores, and returned home.

British troops going ashore in Lake Champlain: Battle of Fort Ticonderoga on 6th July 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

On 1st July 1777, Burgoyne’s army, carried by flotilla and marching down the lake side, arrived just north of Ticonderoga.

Light Infantry under Brigadier Simon Fraser infiltrated around the western side of the fort over Hope Hill. Fraser’s troops crossed the river leading to Lake George and circled around the southern side of Ticonderoga. They climbed Sugar Hill and saw, as Trumbull had, that the heights dominated the American positions both in Fort Ticonderoga and on Mount Independence. The British dragged guns to the summit and opened fire.

St Clair thereupon, after notionally consulting a council of war, resolved to abandon Fort Ticonderoga and retreat south. During the night of 5th/6th July 1777, the American troops left the fort with such supplies as they could take and rowed across to the landings beneath Mount Independence. The secrecy of the move was destroyed by a French officer, Colonel Roche de Fermoy, who set fire to his house on the summit of the hill, lighting up the bay beneath, with its flotilla of boats carrying the American troops across the water.

American soldier: Battle of Fort Ticonderoga on 6th July 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Frank Schoonovere

Alerted to the withdrawal, the British troops pursued, crossing the waterway by boat and the boom from the old French fort, but the Americans made good their escape, marching away into the woods or rowing down the South Bay towards Skenesborough to the South.

An American rear party remained, to contest the British advance and cover St Clair’s withdrawal. That party fell back, leaving a forlorn hope of four men posted at a heavy gun with the duty of firing into the British as they crossed the boom. The redcoats found the four men lying around the gun, incapably drunk, an empty Madeira barrel lying nearby. An inquisitive Iroquois discharged the gun by accident, but caused no injuries, the round howling off into the sky. Fort Ticonderoga was again in British hands and available as a base for their operations south towards Albany.

Casualties at the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777: Casualties were only a few dozen on each side.

Follow-up at the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777:

Fort Ticonderoga was an important symbol for the American colonists, who expected that the fort would keep the redcoats out of the northern colonies, particularly in view of the winter spent improving the fortifications. St Clair’s abrupt retreat caused alarm and outrage. A militant Protestant chaplain in the garrison, the Reverend Thomas Allen, wrote “Our men are eager for the battle, our magazines filled, our camp crowded with provisions, flags flying. The shameful abandonment of Ticonderoga has not been equalled in the history of the world.” This sentiment was repeated with fury across the colonies.

St Clair justified his actions, claiming to have saved valuable troops for the American cause. In the light of the heavy criticism to which he was subjected, he demanded a court martial, at which he was acquitted.

St Clair may have been right. It may be that Burgoyne would have captured a defended Fort Ticonderoga and that many valuable American troops would have become casualties. There is no doubt that Burgoyne’s further march south overstrained the British supply system and contributed directly to his surrender at Saratoga.

Was the fact that the British battery established on Sugar Hill overlooked the American fortifications in Fort Ticonderoga and on Mount Independence an adequate reason for the precipitate and headlong retreat and the abandonment of a major American defence, on which such effort and expectation had been lavished?

In the absence of a direct order from General Schuyler or the Congress to abandon Fort Ticonderoga, perhaps St Clair should have fought it out. Probably, whatever the outcome, St Clair would have emerged from the war a national hero instead of spending the rest of his life attempting to justify his actions and fending off allegations of cowardice.

John Trumbull: Battle of Fort Ticonderoga on 6th July 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: a self-portrait in 1777

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777:

- The artist John Trumbull prepared the report on Fort Ticonderoga in 1776 and painted many scenes from the American Revolutionary War and other important American historical events, including the Declaration of Independence. Trumbull, from Lebanon, Connecticut, served as staff officer to George Washington and painted several portraits of his general. Trumbull’s major works were bought by the United States Congress and hang in the Capitol Building.

- Ethan Allen captured Fort Ticonderoga in 1775 from the small British garrison. He did so with the ‘Green Mountain Boys’ from his home area of Vermont. Allen went on to invade Canada with his ‘Green Mountain Boys’, but was captured and spent two years in prison in England. On his return from England after the war, Allen led the attempt to have Vermont admitted to the United States of America. When this move was unsuccessful, Allen approached the Governor of Canada to have Vermont made part of Canada. This approach was also rebuffed. In 1791, after Allen’s death in 1789, Vermont became part of the USA.

- Colonel Jeduthan Baldwin, General St Clair’s engineer officer built the American schooner ‘Revenge’ at Fort Ticonderoga during the summer of 1776.

- Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko, the Polish Engineer, came to America on the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. At the end of the war he returned to Poland and commanded an insurrection against Russian rule. He died in Switzerland in 1817.

References for the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777:

History of the British Army by Sir John Fortescue

The War of the Revolution by Christopher Ward

The American Revolution by Brendan Morrissey

Saratoga by Richard Ketchum

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Princeton

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Hubbardton

To the American Revolutionary War index