The successful defence of Fort Sullivan on 28th June 1776 by Charleston’s recruit artillerymen against a powerful Royal Navy squadron

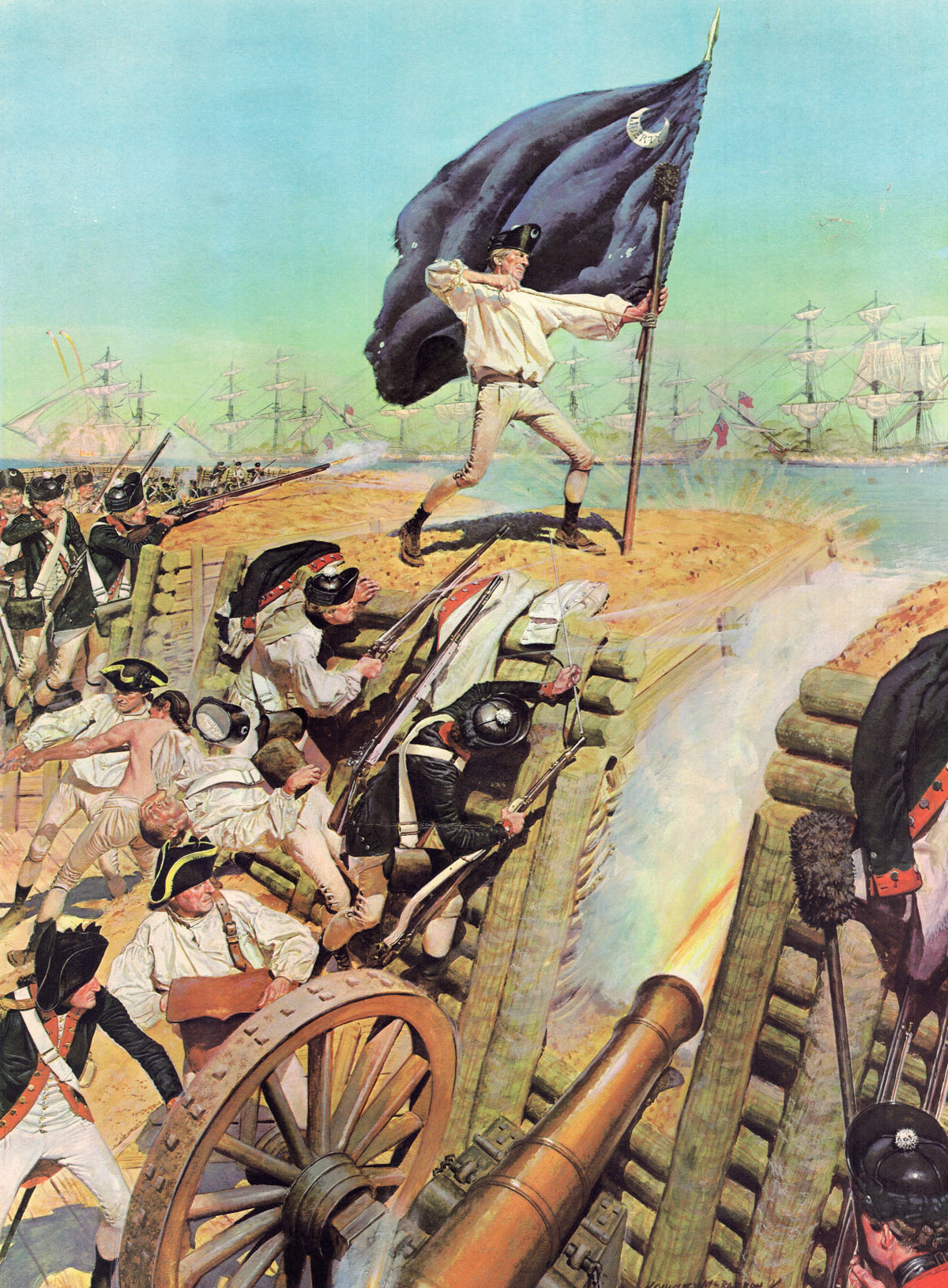

Sergeant William Jasper fastening the South Carolina flag on the rampart of Fort Sullivan at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 in the American Revolutionary War

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Quebec 1775

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Long Island

To the American Revolutionary War index

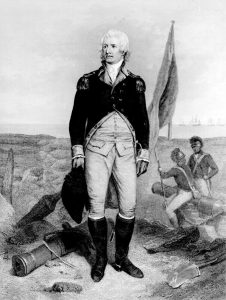

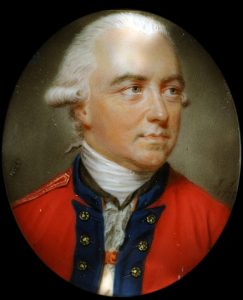

Colonel William Moultrie American commander of Fort Sullivan: Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War

Battle: Sullivan’s Island

War: American Revolution

Date of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island: 28th June 1776

Place of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island: At the mouth of the estuary outside Charleston Harbour, South Carolina, in the United States of America.

Combatants at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island: British Royal Navy and British Army against the American Continental Army and South Carolina Militia and Regiments.

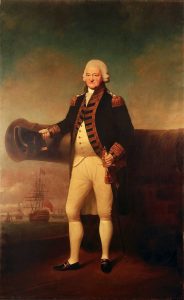

Commanders at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island: Commodore Sir Peter Parker R.N. commanded the Royal Navy squadron. Major-General Sir Henry Clinton commanded the British troops. Major General Charles Lee commanded the American Continental garrison in Charleston. Governor Routledge commanded the local South Carolina forces. Colonel William Moultrie commanded the American troops in the fort on Sullivan’s Island.

Commodore Sir Peter Parker RN commander of the Royal Navy Squadron at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War

Size of the armies at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island: 10 British warships and 2,500 British troops against 6,500 Americans.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island:

The British wore red coats, with bearskin caps for the grenadiers, tricorne hats for the battalion companies and caps for the light infantry.

The Americans dressed as best they could. Increasingly as the war progressed infantry regiments of the Continental Army mostly took to wearing blue uniform coats. The American militia continued in rough clothing.

Both sides were armed with muskets. The British infantry carried bayonets, that were in short supply among the American troops. Both sides were supported by artillery.

Winner of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island: The attack on Sullivan’s Island was a resounding and unexpected success for the American troops.

British Ships and Regiments at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island:

Royal Navy Squadron: HMS Bristol (Flagship), Captain John Morris, 50 guns, HMS Experiment, Captain Alexander Scott, 50 guns, Frigates: HMS Active, Captain William Williams, 28 guns, HMS Actaeon, Captain Christopher Atkins, 28 guns, HMS Solebay, Captain Thomas Symmonds, 28 guns, HMS Syren, Captain Tobias Fourneaux, 28 guns, HMS Friendship, Captain Charles Hope, 22 guns, HMS Sphinx, Captain Anthony Hunt, 20 guns, HM sloop Ranger, Captain Roger Willis, 8 guns, HM schooner St Lawrence, Lieutenant John Graves, 6 guns and HM bomb ketch Thunder, Captain James Reid, 6 guns and 2 mortars.

30 transports carrying the troops.

Major General Sir Henry Clinton: Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War

British Army Regiments: 15th, 28th, 33rd, 37th, 46th, 54th and 57th.

American Units at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island:

On the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, the South Carolina militia was divided in its loyalties between the two sides. To counter this problem the American authorities in the colony raised 6 new regiments of provincial troops and 3 artillery companies, amounting to 2,000 men.

In addition, there were 2 regiment of Continental troops: 2 North Carolina regiments and 1 Virginia regiment amounting to 2,000 men.

The country militia joined the garrison in Charlestown, adding a further 2,000 men.

The Charleston militia supporting the American cause amounted to 700.

The American troops holding Charlestown amounted to 6,500 men.

Background to the Battle of Sullivan’s Island:

The new Royal Governor for the colony of South Carolina, Lord William Campbell, arrived in Charleston on 18th June 1775, the day after the Battle of Bunker Hill.

While there was a strong loyalist element in the population of South Carolina, the sentiment in Charleston was hostile to the British.

When, in September 1775, the Council of Safety in Charleston, after raising troops in support of the American Congress and arming a ship of war, seized Fort Johnson at the entrance to Charleston Harbour, Lord Campbell embarked on the Royal Navy sloop Tamar.

The Royal Governor of North Carolina was forced to leave his post in similar circumstances.

The British government decided to send a military and naval force to act in conjunction with the loyalist elements of the population of North Carolina. A naval squadron, commanded by Commodore Sir Peter Parker, was assembled at Cork in Ireland, with 30 transports to convey a military force, amounting to 2,500 men, to Cape Fear in North Carolina to carry out these operations.

At his request to King George III, Major General the Earl of Cornwallis was appointed to command the military element of the force.

The convoy sailed from Cork on 13th February 1776, but was dispersed by storms, five days into the journey. It took to the 3rd May 1776 for the fleet to arrive at Cape Fear, a journey of almost three months.

Major General Sir Henry Clinton was one of the British major generals despatched to America in 1775, to bolster the resolve of the British commander in chief in Boston, General Thomas Gage. Clinton was sent from Boston to engineer the loyalist uprising in North Carolina.

By the time the Cork re-inforcements were available, the loyalist uprising had taken place and been dispersed by the Americans.

British Royal Navy 50 gun ship at sea: Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War

On 30th May 1776, the Cork flotilla with Clinton’s small force set sail again, this time for Charleston, persuaded by Lord Campbell’s urgings that the recovery of the port of Charleston would considerably advance the British cause. As the senior major general, Clinton commanded.

From January 1776, the Americans in Charleston planned and began to build a new fortification on Sullivan’s Island at the entrance to the estuary, to defend the city from an incursion by the British.

Colonel William Moultrie and his 2nd South Carolina Regiment began building the fort on Sullivan’s Island in March 1776.

By the time the British flotilla arrived off Charleston at the end of May 1776, the fort on Sullivan’s Island was unfinished, but was sufficiently advanced to provide a substantial defence to the city.

The fort on Sullivan’s Island was planned as a square redoubt, with bastions at each corner. The construction was of an inner and an outer wall, made with palmetto trunks up to a height of twenty feet, with the sixteen-foot space between the walls filled with sand. The side facing the sea was complete, with bastions in place. The sides facing away from the sea appear to have been still under construction when the battle took place. The fort was, until being re-named Fort Moultrie after the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, referred to as Fort Sullivan.

On seeing the uncompleted fort, General Charles Lee recommended that it be abandoned, describing it as a ‘Slaughter Pen’. Acting on Colonel Moultrie’s advice, Governor Routledge refused to leave the fort.

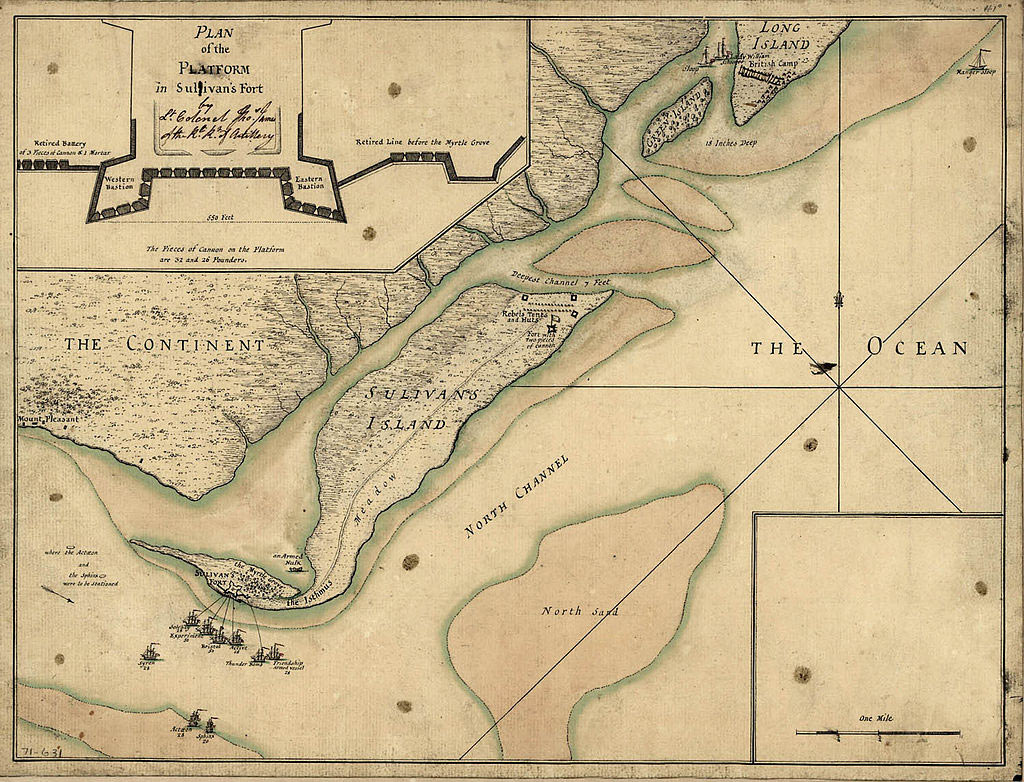

Plan of the attack on Fort Sullivan 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War: plan by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas James Royal Artillery

Guns at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island:

A plan of the fort was prepared by an officer of the Royal Artillery, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas James after the battle. The plan appears to show 28 pieces of artillery in Fort Sullivan. One is described as a mortar and the rest as being 32 and 26 pounders. It is apparent from the caption on the plan that Colonel James took his information from officers present at the battle, if he was not himself present, which is not clear. Possibly information was obtained when the fort, by then called Fort Moultrie, was taken by the British when they captured Charleston in 1780.

Ward describes the cannon in Fort Sullivan in these terms: ‘Along the front were mounted six 24-pounders and three 18-pounders. Along the southerly side were six guns, 9- and 12-pounders. In each bastion were five guns, ranging from 9 to 26 pounders.’ Ward describes three 12-pounders as mounted in each of the other two bastions. The difficulty with Ward’s description is that he puts the ‘front’ in contradistinction to the ‘southerly side’. It would seem that the southerly side of the fort was the front.

View of Charleston in 1771: Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War

It seems likely that the guns available to the Americans were those they removed from the other long-standing British coastal batteries. It is very unlikely that a coastal battery would have mounted a cannon smaller than an 18-pounder. James, the producer of an apparently contemporaneous and professionally informed plan, refers only to 32 and 26 pounders.

If James is correct the British ships were heavily out-gunned by Fort Sullivan.

The largest British ship, HMS Bristol, carried twenty-two 24 pounder guns, twenty-two 12 pounder guns and other smaller cannon. Experiment carried the same size and number of guns. The frigates deployed nothing larger than 9 pounders.

The report of damage suffered during the Battle of Sullivan’s Island by HMS Bristol describes being struck by 32 pounder cannon balls.

Account of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island:

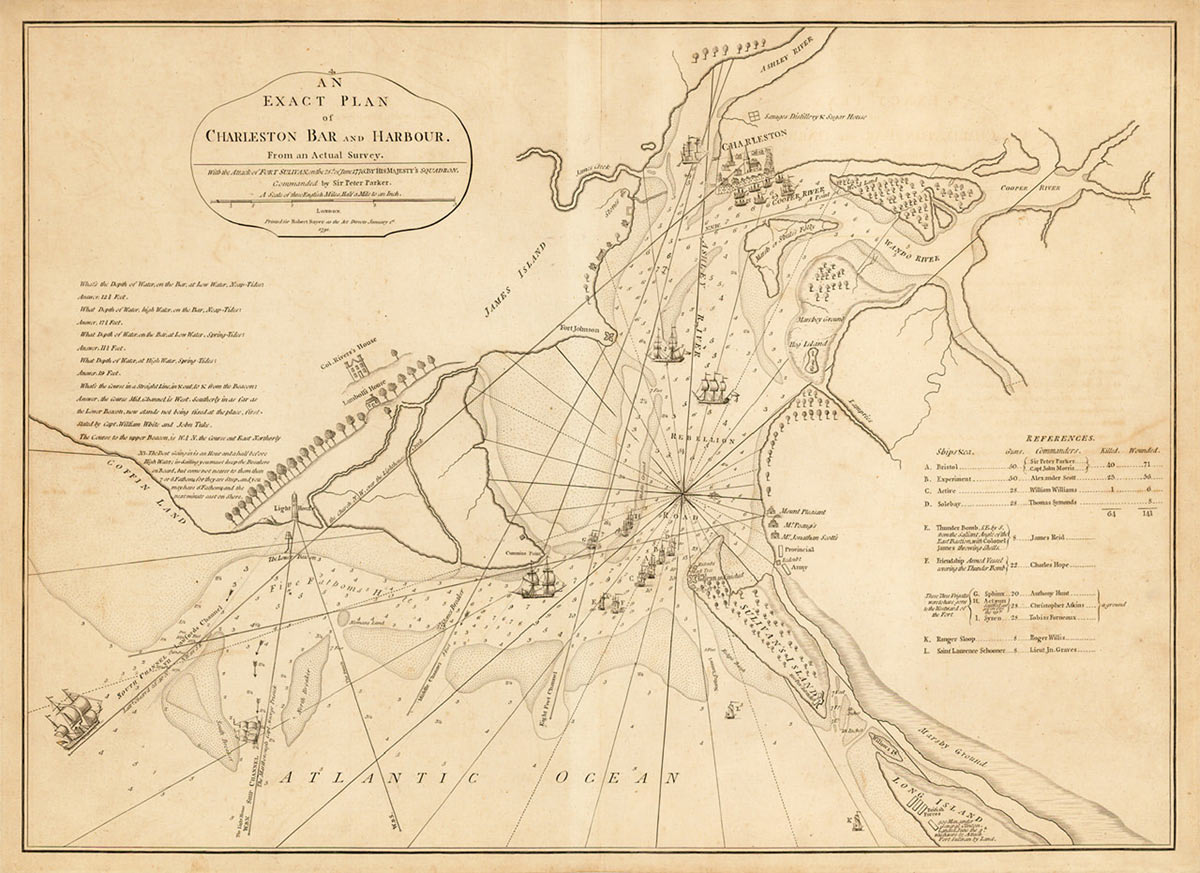

The British flotilla arrived off Charleston on 4th June 1776. There was much work to be done. It seems unlikely that the British had access to reliable charts of the estuary, an infinitely complex area with sandbanks and intricate channels giving access to the inner harbour. The Americans will have removed all navigation aids. Time was spent taking soundings and putting in buoys.

It took until 7th June 1776 to get the frigates and transports over the bar and into ‘Five Fathom Hole’, an area of open water against the shore to the west of the main estuary.

Charleston was an important port for the southern colonies, and it is surprising that there was not a shipping channel giving access to the harbour. It may be that the Royal Navy ships were unable to find the normal shipping channel and were forced to cross one of the shoals, or, that the two 50 gun ships were too large to have access to Charleston harbour. Certainly, the Royal Navy found that its larger ships were limited in the access available to them on the American coast.

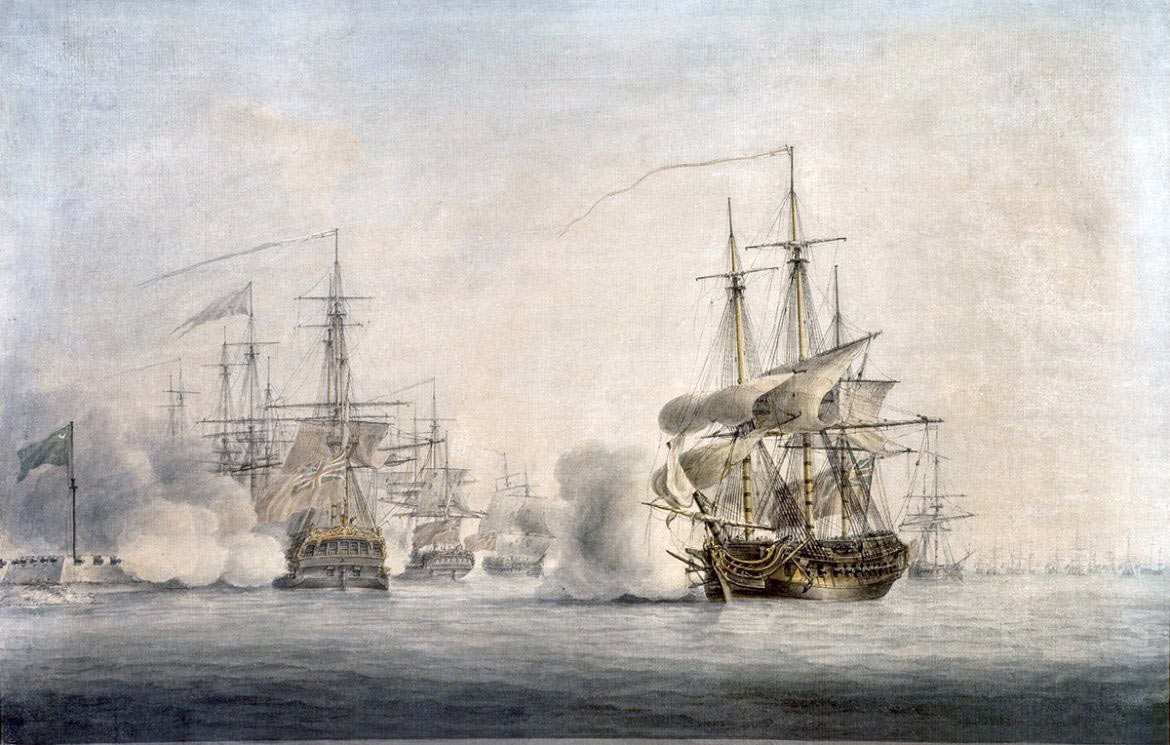

The attack on Fort Sullivan: Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by Nicholas Pocock

The British plan was to land the military units on Long Island, the island next up the coast to the north-east of Sullivan’s Island, cross the channel between Long Island and Sullivan’s Island, called ‘the Broad’, and attack Fort Sullivan in the rear.

General Clinton received information that the channel between Long Island and Sullivan’s Island at low tide was only eighteen inches deep. This erroneous information was not checked before the operation was begun.

The attack on Fort Sullivan: Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War

On 9th June 1776, 500 British troops landed on Long Island. An attempt was made by a force of the 15th Regiment and the light infantry and grenadier companies of the other regiments to cross the channel to Sullivan’s Island.

In the light of the threat from the British on Long Island, General Lee hurried a force of 800 American troops commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William Thompson, comprising 3rd Regiment of South Carolina Rangers, North Carolina Continentals, South Carolina troops and militia and the ‘Raccoon’ Company of riflemen onto Sullivan’s Island, and moved them to the north of the island to face the oncoming British. Two American guns were brought to the north end of Sullivan’s Island and installed in an earthwork.

Map of Charleston Harbour and Estuary: Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War

The channel between Long Island and Sullivan’s Island, ‘the Breach’, turned out to be a patchwork of shoals and subsidiary channels up to seven feet deep. The boats carrying the British soldiers grounded on the shoals and the soldiers found the channels too deep to wade across. In any case, there were only enough ship’s boats available to carry around 500 men across at a time, insufficient for an attack on a prepared position supported by guns.

On 10th June 1776, the remainder of the British troops landed on Long Island, but there was now no prospect of a successful crossing of the difficult channel. The two sides relapsed into a long range and sporadic exchange of cannon fire.

It took two weeks, until 27th June 1776, for Commodore Sir Peter Parker to kedge his two 50 gun warships across the bar and into Five Fathom Hole, an operation that required the removal of the ships’ guns to lighten them sufficiently.

On 28th June 1776, the bomb ketch HMS Thunder, escorted by HMS Friendship, moved across the estuary, anchored a mile and a half from Fort Sullivan and opened fire on the fort, the Thunder firing ten inch mortar shells.

During the morning, the first line of British warships, HMS Active, Bristol, Experiment and Solebay anchored in a line within four hundred yards of the fort, and, regulating their movement by way of spring cables attached to their anchor lines, opened fire on the fort.

The second line of warships, HMS Syren, Actaeon and Sphinx, took up positions covering the gaps between the first line ships and also opened fire.

The American gunners began to return the fire, with the major disadvantage that there was only enough gun powder in the fort for thirty-five rounds per gun. Each shot was carefully aimed, in contrast to the broadsides fired by the ships. There does not appear to have been any shortage of cannon balls in the fort. Chain shot was used to destroy the ships’ rigging.

Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Henry Grey an officer of the American garrison in Fort Sullivan wounded during the battle

After an hour of firing, acting on the commodore’s order, the second line ships weighed anchor and moved off up the estuary. The intention was that these three ships would move around the headland into the inlet behind the fort, and bombard the garrison in enfilade, the shots striking the area of the fort that was incomplete and provided least protection to the American gunners.

The second line ships, Actaeon, Sphinx and Syren, sailing up the estuary, suddenly grounded on an area of shoal called the Middle Ground, positioned, as the name suggests, in the middle of the estuary.

As these ships went aground, Sphinx ran into Actaeon, losing her bowsprit. By the end of the day’s fighting, Sphinx and Syren got themselves clear, although damaged. Actaeon was stuck fast.

The bombardment between the first line ships and the fort continued.

Morning after the Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Henry Grey an American officer present in Fort Sullivan and wounded during the battle: HMS Actaeon burning in the foreground

The fort was struck repeatedly by several thousand cannon balls, but the palmetto trunks used in the structure absorbed the shock of the strikes and the fort’s structure remained intact.

The American gunners were protected by the sixteen-foot-thick sand and timber walls and suffered few casualties.

It was quite the reverse for the British ships of the first line. Commodore Sir Peter Parker had little idea what to expect from the fort before he engaged it. What he clearly did not anticipate was a fully functioning battery, with immensely strong walls, the largest of cannon and a well-motivated garrison able to operate their guns with precision and determination.

American defence of Fort Sullivan: Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War

The British ships were too close to engage with such an enemy. Both 50 gun ships had their anchors shot away and, swinging round, took shots in the stern that hurtled the full length of the ship, killing and maiming crew, dismounting guns, smashing bulkheads and equipment and blasting holes at each end of the hull.

General Charles Lee visited Fort Sullivan during the afternoon. Seeing the low state of the ammunition supply he sent over a further 700 pounds of gun powder from the city. By the time the powder arrived, the fort’s guns had been silent for an hour. They resumed firing.

The bombardment continued until 11pm, when the British ships cut their cables and made their way back down the estuary. The battle was over.

The next morning showed the Actaeon to be firmly stuck on the Middle Ground shoal. The crew set her on fire and came away in her boats.

Casualties at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island:

The British casualties were all from the Royal Navy.

The American fire had been concentrated on the two largest ships, HMS Bristol and HMS Experiment. The captain of Bristol, Captain John Morris, was killed as were 39 others of his crew, with 71 wounded. Commodore Sir Peter Parker was wounded. Captain Alexander Scott of HMS Experiment lost an arm. 23 of his crew were killed and another 55 wounded. Active had 1 killed and 6 wounded. Solebay had 5 wounded.

The damage to HMS Bristol, reported by the ship, confirmed the presence of 32 pounder cannon in Fort Sullivan. Bristol’s mizzenmast was hit by seven 32 pounder cannon balls and had to be cut away. Twice, American gunfire cleared the quarterdeck of all personnel, other than the commodore, who was wounded in the leg. The top of the mainmast was carried away. Seventy cannon balls struck the ship in the hull. The comment is made that Bristol would probably not have survived had the weather been rough.

Experiment was heavily damaged, but not as badly as the flagship.

HMS Actaeon was lost entirely, although all her crew got away by boat.

Americans casualties were 17 dead and 20 wounded. 7,000 British cannon balls were collected on Sullivan’s Island after the battle.

British Squadron in ‘Five Fathom Hole’ the morning after the Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 during the American Revolutionary War: picture by a British officer present at the battle: Actaeon is on fire: HMS Bristol can be seen with a mast missing. Charleston is in the distance

Follow-up to the Battle of Sullivan’s Island: Clinton’s troops remained on Long Island for a further three weeks. Once it was clear that nothing further could be achieved against the Americans in Charleston, the British troops embarked on the transports and, escorted by HMS Solebay, headed for New York and the Battle of Long Island.

The other British warships remained in the estuary carrying out the repairs necessary to make them seaworthy.

Following the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, the British made no attempt to attack the Americans in the Southern Colonies for another two years.

Sergeant William Jasper fastening the South Carolina flag at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island on 28th June 1776 in the American Revolutionary War

Anecdotes from the Battle of Sullivan’s Island:

- Drayton’s Memoirs of the American Revolution in Relation to South Carolina records in the Appendix that an American deserter from Colonel Gadsden’s First South Carolina Regiment, called M’Neil, informed Commodore Sir Peter Parker that the guns in Fort Johnson had been spiked. If this is what happened, it may be an explanation as to why Parker appeared to treat the fort on Sullivan’s Island with so little care, in the belief that none of the big guns from Fort Johnson could be used against his ships.

- A British surgeon in a Royal Navy ship at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island wrote of the Americans: ‘Their artillery was surprisingly well served. The fire was slow, but decisive indeed; they were very cool and took care not to fire except their guns were exceedingly well directed.’

- The American commander in Charleston, the ex-British officer General Charles Lee wrote of the Fort Sullivan garrison: ‘the behaviour of the garrison, both men and officers, with Colonel Moultrie at their head, I confess astonished me. It was brave to the last degree. I had no idea that so much coolness and intrepidity could be displayed by a collection of raw recruits.’

- One of the Fort Sullivan American garrison was Sergeant William Jasper of Colonel Moultrie’s 2nd South Carolina Regiment. The fort was flying from the flagpole the newly designed South Carolina flag. The flagpole was shot away during the bombardment. Jasper climbed out through an embrasure, retrieved the flag and displayed it on the end of a gun sponge staff. The flag was blue with a white crescent and the word ‘Liberty’ emblazoned on it. After the battle Governor Rutledge presented Jasper with his sword and offered to make him an officer. Jasper refused this offer as he was unable to read or write and considered he could not carry out an officer’s duties. Sergeant Jasper arrived in Pennsylvania in 1767, aged 16 years, as an immigrant indentured servant from Germany. His name was then Johann Wilhelm Gasper. The colonist to whom Gasper was indentured changed his name to Jasper. Jasper moved south after completing his period of indenture, to find a farm for himself and his wife Elizabeth. Sergeant Jasper was mortally wounded during the American attack on Savannah in 1779. Counties were named after Jasper in several of the new American states.

- HMS Bristol, after the damage inflicted by the guns of Fort Sullivan was repaired, made for the West Indies, where, in 1778, she received a new lieutenant, Horatio Nelson.

- Lord William Campbell, the displaced Royal Governor of South Carolina, served as a volunteer naval gunner on board the Flagship, HMS Bristol, during the Battle of Sullivan’s Island. Lord Campbell received a wound that eventually killed him.

- Lieutenant Henry Gray, whose two pictures of the Royal Navy Squadron attacking Fort Sullivan appear above, was an officer in Colonel Moultrie’s 2nd South Carolina Regiment of Infantry. Gray was wounded in the leg during the Battle of Sullivan’s Island. Later, Gray took part in the attack on Savannah on 9th October 1779, and was killed attempting to plant the French standard and the regimental flag on the British parapet. He was immediately followed in planting the two colours by Sergeant Jasper, who was mortally wounded.

References for the Battle of Sullivan’s Island:

Drayton’s Memoirs of the American Revolution in Relation to South Carolina

History of the British Army by Sir John Fortescue

The War of the Revolution by Christopher Ward

The American Revolution by Brendan Morrissey

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Quebec 1775

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Long Island

To the American Revolutionary War index