The surrender of General Burgoyne’s British Army to the American Colonists on 17th October 1777, bringing France and Spain into the war

Capitulation of the British at the Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: print by Fauvel

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Germantown

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Monmouth

To the American Revolutionary War index

Battle: Saratoga

War: American Revolutionary War

Date of the Battle of Saratoga: 17th October 1777

Place of the Battle of Saratoga: Saratoga on the Hudson River in New York State.

Combatants at the Battle of Saratoga: British and German troops against the Americans.

Major-General John Burgoyne: Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Joshua Reynolds

Generals at the Battle of Saratoga: Major General John Burgoyne commanded the British and German force. Major General Horatio Gates and Brigadier Benedict Arnold commanded the American army.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Saratoga: The British force comprised some 5,000 British, Brunswickers, Canadians and Indians. By the time of the surrender the American force was around 12,000 to 14,000 militia and troops.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Saratoga: The British wore red coats, with bearskin caps for the grenadiers, tricorne hats for the battalion companies and caps for the light infantry.

The German infantry wore blue coats and retained the Prussian style grenadier mitre cap with brass front plate.

The Americans dressed as best they could. Increasingly as the war progressed regular infantry regiments of the Continental Army wore blue or brown uniform coats, but the militia continued in rough clothing.

Major-General Benedict Arnold: Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

The British and German troops were armed with muskets and bayonets. The Americans carried muskets, largely without bayonets. Virginia and Pennsylvania regiments, particularly Morgan’s men and other men of the woods carried long, small calibre, rifled weapons. cannons, mostly of small calibre.

Winner of the Battle of Saratoga: The Americans forced the surrender of Burgoyne’s force.

British Regiments at the Battle of Saratoga:

The senior officers were Major General William Phillips, Baron Riedesel, Brigadier Simon Fraser and Brigadier Hamilton.

Major Lord Balcarres commanded the light companies of the regiments of foot.

Major Acland commanded the grenadier companies of the same regiments.

The battalion companies of the 9th, 20th, 21st, 24th, 29th, 31st, 47th, 53rd and 62nd Foot.

Breyman’s Jägers, Riedesel’s Regiment, Specht’s Regiment, Rhetz’s Regiment and Captain Pausch’s Hesse Hanau Company of artillery

Indians and Canadians.

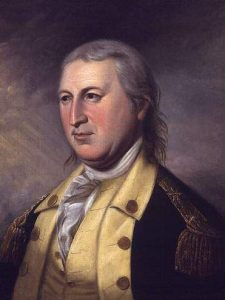

Major-General Horatio Gates: Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

The American Army at the Battle of Saratoga:

Right Wing:

Under the personal command of General Horatio Gates:

Brigadier Glover’s Continental Brigade, Colonel Nixon’s Continental Regiment and Brigadier Paterson’s Continental Brigade

Centre:

Brigadier Learned’s Continental Brigade, Bailey’s Massachusetts Regiment, Jackson’s Massachusetts Regiment, Wesson’s Massachusetts Regiment and Livingston’s New York Regiment

Left Wing:

Commanded by Major General Benedict Arnold

Brigadier Poor’s Brigade, Cilley’s 1st New Hampshire Regiment, Hale’s 2nd New Hampshire Regiment, Scammell’s 3rd New Hampshire Regiment, Van Cortlandt’s New York Regiment, Livingston’s New York Regiment, Connecticut Militia, Morgan’s Riflemen and Dearborn’s Light Infantry

Background to the Battle of Saratoga: Over the winter of 1776/7, the British Government in London devised a plan to send a strong army down the Lake Champlain route from Canada into the heart of the rebellious American Colonies, isolating New England.

Colonel John St Leger: Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Joshua Reynolds

The British Governor of Canada, Sir Guy Carleton, with his experience of campaigning in North America, would have been a sound appointment for this command, particularly after his determined and resourceful defence of Canada in 1775 and 1776. Instead, Lord Germaine, the minister in London with direct control of the British war policy, persuaded King George III to appoint Major-General John Burgoyne, Carleton’s subordinate during 1776, as commander-in-chief of the expedition from Canada. Burgoyne took the precaution of returning to London during the winter to lobby for the command.

Strong reinforcements of British and Brunswick regiments of foot and artillery were sent to Canada. Germaine’s instructions to Burgoyne were to take the best of these regiments down Lake Champlain, capture Fort Ticonderoga, advance to the Hudson River and progress south.

Lord Germaine’s and Burgoyne’s expectations were that a second British force under Major General Clinton would move north, up the Hudson River from New York, and meet Burgoyne, but no proper orders were sent to General Howe, commanding the British forces in New York, to ensure that he complied with this expectation. General Howe, the British commander-in-chief in the central colonies had his own plans to invade Pennsylvania and take Philadelphia.

Burgoyne’s army set off from the St Lawrence River down Lake Champlain at the end of June 1777, reaching Fort Ticonderoga on 1st July 1777. The American commander abandoned the fort (see the Battle of Ticonderoga 1777) as the British and Brunswickers arrived.

The British Colonel St Leger advanced down the Mohawk River from Lake Erie with a British force in a diversionary raid.

On 10th July 1777, Burgoyne’s force reached Skenesboro, at the southern end of Lake Champlain, where it concentrated on clearing the road to the North for supplies and to the South for the advance. The forested country, crossed by primitive tracks rather than roads, was difficult for an army having to move quantities of supplies and artillery.

General Schuyler, the American commander, withdrew to Stillwater, thirty miles north of Albany, Burgoyne’s primary target. The American authorities made determined efforts to raise the New England militia and to implement a scorched earth policy in the path of the British advance.

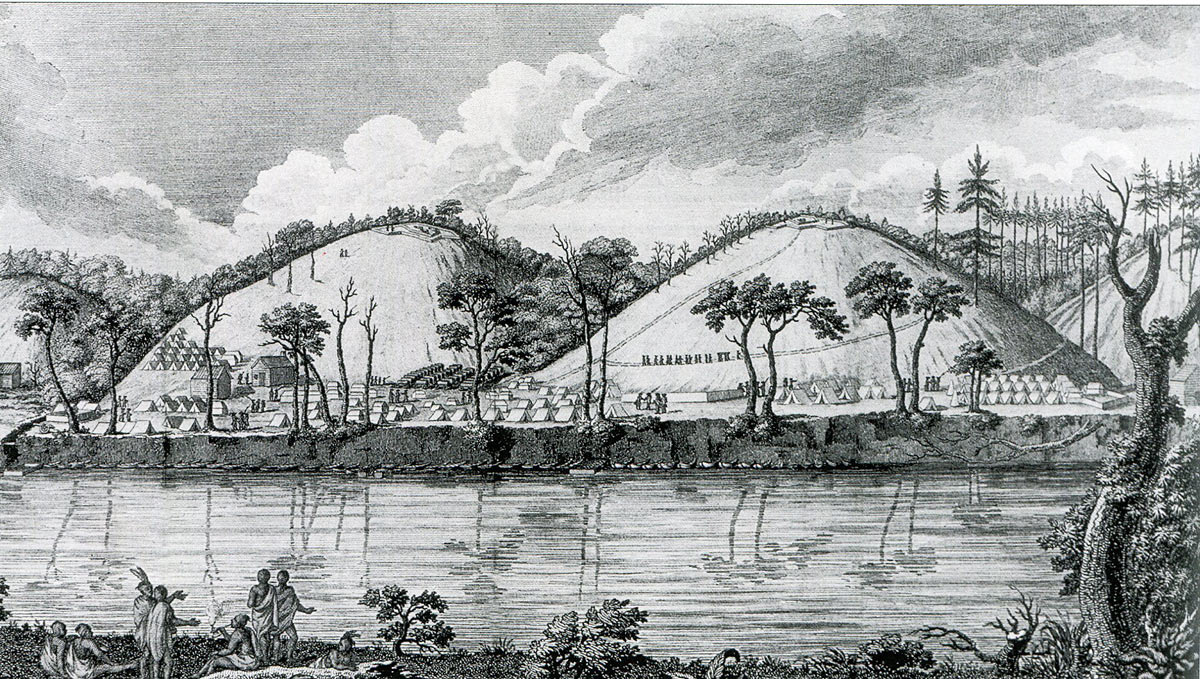

To obtain additional supplies and horses for his Brunswick dragoon regiment, Burgoyne sent the German, Colonel Baum, with 500 men on a raid to Bennington, New Hampshire. Simultaneously Burgoyne moved his army down the Hudson River to Saratoga, where he built a substantial fortified camp.

British lines at Saratoga seen from across the Hudson River: Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

Baum’s force was attacked by American militia and overwhelmed. A relieving force commanded by Colonel Breymann was repelled with some loss (see the Battle of Bennington).

St Leger found that difficulties with his Indian allies and the vigorous resistance of Brigadier Benedict Arnold forced him to abandon his advance down the Mohawk River.

Burgoyne was in a perilous position. The presence of his army was arousing the local militia in substantial numbers. He was short of food. Germaine’s imperative orders to march south restrained Burgoyne from remaining where he was, from retreating northwards or from diverting to the East.

Brigadier Simon Fraser of Balnairn: Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

It took Burgoyne until 13th September 1777 to assemble sufficient supplies, dragged through the forests down rudimentary roads, to enable his army to continue the advance south.

On 19th September 1777, Burgoyne’s army approached the fortified American camp on the west bank of the Hudson River at Bemis Heights.

The British force advanced on the American army, now commanded by the ex-British officer, Major-General Horatio Gates, in three columns, one by the river under the German officer, Colonel Riedesel, the main force in the centre commanded by Burgoyne himself, and the third, commanded by Brigadier Simon Fraser, making a wide outflanking detour to the American left. The aim of the British was to take the unfortified hill to the West of the American positions on Bemis Heights.

Arnold pressed Gates to leave his entrenchments and attack the British but he was reluctant to take what he saw as the risk of moving out of his fortified camp.

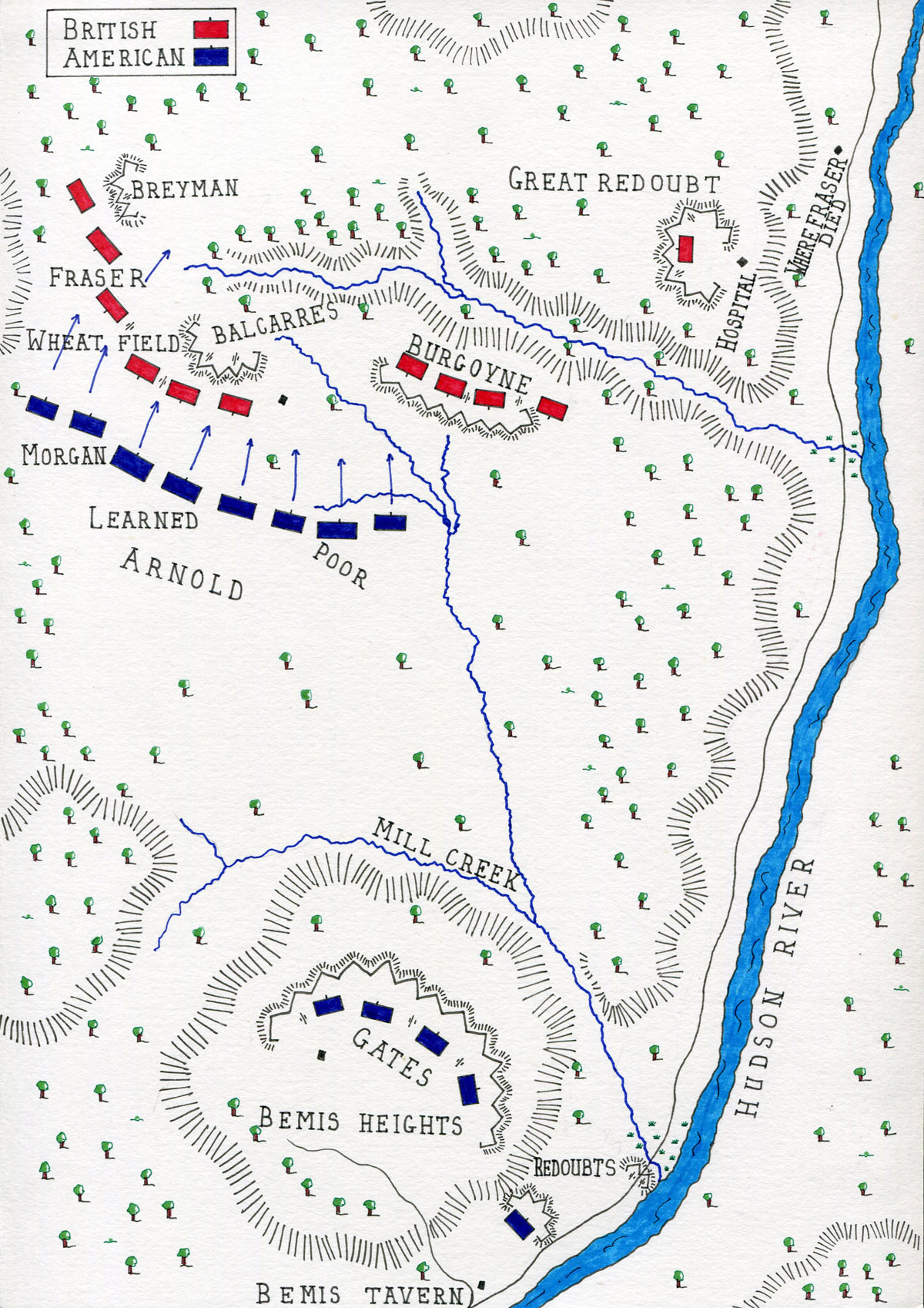

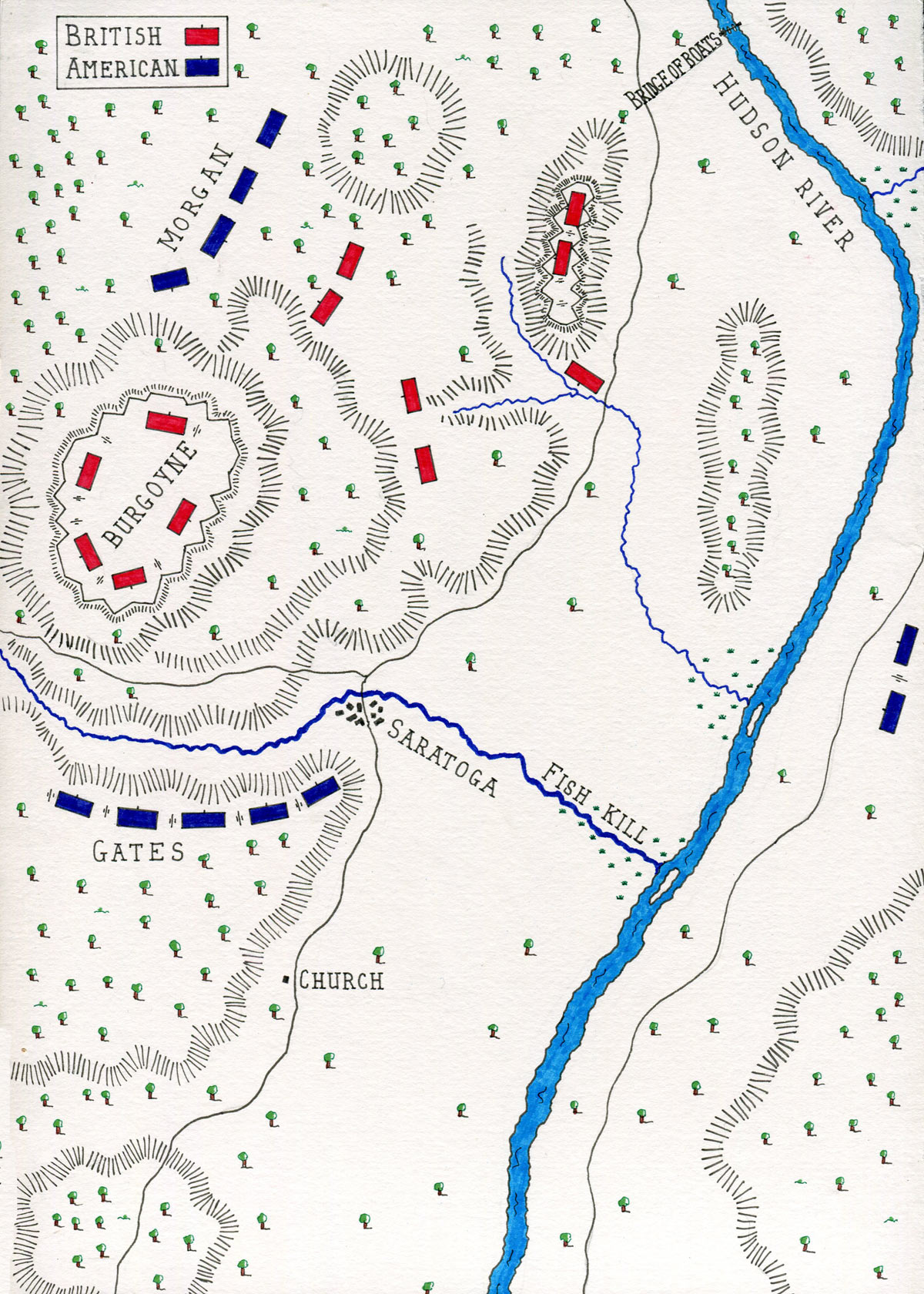

Map of the American attack on 7th October 1777 at the Battle of Saratoga in the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

Burgoyne deployed his battalions for the attack; the 9th, 21st, 62nd and 20th Foot. Fraser came up on the right, with the Grenadiers, Light Companies and the 24th Foot, towards the heights on the American left, and Riedesel began his approach along the riverbank. This phase of the battle was known as the Battle of Freeman’s Farm and was hard fought, leaving the British in occupation of the ground at nightfall.

Account of the Battle of Saratoga: The next day, 20th September 1777, several of Burgoyne’s senior offices urged him to renew the attack on the American positions. It is suggested that if he had done so he would have taken advantage of the disarray into which the previous day’s hard fighting had thrown Gates’s army. Although initially tempted by the proposal, Burgoyne finally rejected it and remained in his camp by the Hudson River.

Benedict Arnold leading the American attack at the Battle of Saratoga on 7th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

On the same day, Burgoyne received word that the Americans had captured one of his supply flotillas on Lake George. He was tempted to abandon the whole enterprise and withdraw to Fort Ticonderoga, but information that Major-General Clinton was advancing to meet him, up the Hudson River from New York, caused Burgoyne to remain in his camp.

By 7th October 1777, despite considerable success in the southern reaches, Clinton had not made any real progress up the Hudson River. Burgoyne determined to launch the delayed attack on the American positions on Bemis Heights. By this time, Gates had been considerably reinforced and his army comprised some 12,000 men against around 4,000 British and Germans.

Burgoyne described the operation as a reconnaissance in strength, designed to see if he could occupy the hill to the West of the American fortifications on Bemis Heights.

General Benedict Arnold wounded at the Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

The American piquets sent word that the British had advanced and were forming up in a wheat field near the old Freeman’s Farm battlefield. Morgan’s riflemen were committed to the attack, quickly supported by the other regiments of Arnold’s division. The Americans far outnumbered the British “reconnaissance” party and the British Grenadiers and Light Companies were pressed back.

Mortal wounding of Brigadier Simon Fraser of Balnairn at the Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

At a critical moment in the fighting, Brigadier Simon Fraser was mortally wounded by one of Morgan’s riflemen. Arnold spurred the Americans to continue the attack and was himself severely wounded. The British and Hessian troops began to give way and, after the redoubt held by Colonel Breyman and his regiment was taken, Burgoyne withdrew the force to his fortified camp above the Hudson River.

Surrender of General Burgoyne and the British Army to General Gates at the Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

The next day, 8th October 1777, Burgoyne withdrew his army up the river to the camp they had built at Saratoga. The American army followed and enveloped the British positions. Burgoyne let the last opportunities to retreat north to Ticonderoga go by, hoping that Clinton’s army would come up the Hudson River from the South to his relief. A major difficulty in the campaign was communication between the two British forces. Almost all the messengers attempting the journey between Burgoyne and Clinton were caught and hanged by the Americans.

Map of the the Battle of Saratoga in the American Revolutionary War on 17th October 1777 at the time of Burgoyne’s surrender: map by John Fawkes

Burgoyne awaited news of Clinton’s advance until 17th October 1777, when he was forced to sign the convention by which his troops surrendered to Gates, who had by then between 18,000 and 20,000 men.

Casualties at the Battle of Saratoga: Of the 7,000 British and Germans who marched from Canada only 3,500 were fit for duty at the surrender.

Burial of Brigadier Simon Fraser at the Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by John Graham

Follow-up to the Battle of Saratoga: The consequences of Burgoyne’s surrender were catastrophic for Britain. France entered the war on the side of the American colonists in 1778, followed by Spain in 1779, and the American effort in the war was galvanized.

Anecdotes and Traditions from the Battle of Saratoga:

- It is said that Benedict Arnold pointed out Brigadier Simon Fraser as a prominent mounted British officer to Daniel Morgan and ordered him to have one of his riflemen shoot him. Morgan reluctantly ordered Timothy Murphy to shoot Fraser which he did.

- General Burgoyne was known to the British troops as ‘Gentleman Johnnie’. Burgoyne made his name in the Seven Years War in Portugal commanding a regiment of light dragoons.

- Major Lord Balcarres, the commander of the British Light Infantry at the Battle of Freeman Farm and the Battle of Saratoga, after the American Revolutionary War met Benedict Arnold in England. Balcarres snubbed Arnold for being a traitor to the American cause by deserting to the British and the two men fought a duel. Neither was injured.

- General Burgoyne was so confident of his success in attacking down the Lake Champlain route that he bet Charles James Fox £10 that he would return to London victorious within the year. In later life, General Burgoyne became a successful play-write with ‘The Maid of the Oaks’ and ‘The Heiress’. He wrote the libretto for the opera ‘The Lord of the Manor’.

- With the loss of the Battle of Saratoga, General Burgoyne insisted that he would not ‘surrender’ to the Americans. He would only enter into a ‘Convention’. General Horatio Gates agreed. By the terms of the convention the British officers were permitted to return to Britain, but could not take any further part in the war. The soldiers were interned by the Americans. General Washington repudiated the terms of the Convention when he was informed and the British soldiers became prisoners of war. The British continued to act as if the Convention was in force. The British regiments held by the Americans were counted as part of the British active army. Soldiers from these regiments who escaped from American captivity were labelled by the British authorities as deserters!

- Major General Horatio Gates: Gates was an English officer who served in North America, commanding one of the Independent Companies from New York in General Braddock’s ill-fortuned attempt to capture Fort DuQuesne in 1755, and becoming a friend of George Washington. After the French and Indian War, Gates married an American and bought an estate in Virginia. On the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, Gates’ experience in military administration with the British Army and Washington’s influence ensured him the appointment of Adjutant General of the Continental Army. Gates sought a field command and was appointed to command the American army at Fort Ticonderoga in 1776. With the withdrawal to Canada of the British force in the autumn of 1776, Gates joined Washington in New Jersey. Gates lobbied hard to be given command of the American field army in place of Washington, but Washington’s successes at the Battles of Trenton and Princeton confirmed his position and Gates returned to the Hudson to resist the advance of Burgoyne and there received Burgoyne’s capitulation. Following this success, Gates again plotted to acquire the command in chief of the American army from George Washington, but was unsuccessful. In 1780 Gates was appointed to command the American forces in North Carolina and was soundly defeated by the British under General Cornwallis at the Battle of Camden. Gates was replaced in command by General Nathaniel Green and finished the war on Washington’s staff. Gates retired to Manhattan with his second wife.

References for the Battle of Saratoga:

History of the British Army by Sir John Fortescue

The War of the Revolution by Christopher Ward

The American Revolution by Brendan Morrissey

Saratoga by Richard Ketchum

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Germantown

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Monmouth

To the American Revolutionary War index