‘The Moonlight Battle’: Admiral Sir George Rodney’s decisive naval victory on 16th January 1780 over a Spanish Fleet, that enabled Rodney to re-supply Gibraltar

‘The Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Richard Paton: Rodney’s flagship HMS Sandwich is in the foreground with the Spanish ship San Domingo exploding to the front of Sandwich.

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Great Siege of Gibraltar

The next battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Storming of Seringapatam

To the American Revolutionary War index

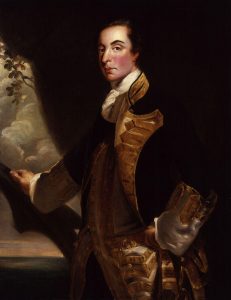

Admiral Sir George Rodney: Rodney’s ‘Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War

War: the American Revolutionary War.

Date of the Battle of Cape St Vincent: 16th January 1780.

Place of the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780: Off the south-west coast of Portugal, to the west-north-west of the Spanish naval port of Cadiz.

Combatants at the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780: A British Fleet against a Spanish Fleet.

Commanders at the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780: Admiral Sir George Rodney against Admiral Don Juan de Langara.

Winner of the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780: The British Fleet won the battle.

The Fleets at the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780:

British Fleet: Sandwich flagship of Admiral Rodney (Captain Walter Young 90 guns), Royal George flagship of Rear Admiral Sir John Lockhart-Ross (Captain John Bourmaster 100 guns), Prince George flagship of Rear Admiral Robert Digby (Captain Philip Patton 98 guns), Monarch (Captain Duncan 74 guns), Edgar (Captain Elliot 74 guns), Bedford (Captain Affleck 74 guns), Alcide (Captain Brisbane 74 guns), Culloden (Captain Balfour 74 guns), Terrible (Captain Douglas 74 guns), Defence (Captain Douglas 74 guns), Resolution (Captain Sir Chaloner Ogle 74 guns), Ajax (Captain Uvedale 74 guns), Montagu (Captain Houlton 74 guns), Invincible (Captain Cornish 74 guns), Alfred (Captain Bayne 74 guns), Cumberland (Captain Peyton 74 guns), Marlborough (Captain Penny 74 guns), Bienfaisant (Captain MacBride 64 guns), Prince William (Lieutenant Gower 64 guns) and frigates: Apollo (Captain Pownall 32 guns), Pegasus (Captain Bazely 28 guns), Triton (Captain Lutwidge 28 guns), Hyaena (Captain Thompson 24 guns) and Porcupine (Captain Seymour Conway 24 guns).

HMS Sandwich, Admiral Rodney’s flagship at ‘the Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War

Spanish Fleet: Fenix flagship of Admiral Don Juan de Langara 80 guns, Princesa (70 guns), Diligente (70 guns), Monarca (70 guns), San Augustin (70 guns), San Eugenio (70 guns), San Jenaro (70 guns), San Justo (70 guns), San Lorenzo (70 guns), San Domingo (70 guns), San Julian (64 guns) and frigates: Santa Cecilia (34 guns) and Santa Rosalia (34 guns).

Admiral Juan de Langara: Spanish admiral at Rodney’s ‘Moonlight Battle,’ Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War

Ships and Armaments at the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780: Sailing warships of the 18th and 19th Century carried their main armaments in broadside batteries along the sides. Ships were classified according to the number of guns carried or the number of decks carrying batteries. The size of gun on the line of battle ship was up to 32 pounder, firing heavy iron balls or chain and link shot designed to wreck rigging.

Ships manoeuvred to deliver broadsides in the most destructive manner; the greatest effect being achieved by firing into an enemy’s stern or bow, so that the cannon balls travelled the length of the ship wreaking havoc and destruction. The first broadside, loaded before action began and often double shotted, was always the most effective. To achieve greatest impact the British ships held their fire until alongside the Spanish ships. In some instances, broadsides were fired at ranges of less than 10 metres.

Ships carried a variety of smaller weapons on the top deck and in the rigging, from swivel guns firing grape shot or canister (bags of musket balls) to hand held muskets and pistols, each crew seeking to annihilate the enemy’s officers and sailors on deck.

British captains expected their ships to clear for action in ten minutes. Cabin walls were dismantled; gun crews formed up; the gunner and his mates opened the magazine and distributed ammunition for the guns; decks were wetted and sprinkled with sand; the surgeon laid out his implements in the cockpit; the marines assembled to take post on the decks or in the rigging. The final act of preparation was for the gun ports to be opened and the guns run out, the truck wheels rumbling through the ship.

Ships of the Spanish navy were not competently handled. The crews were not well drilled and took hours to perform functions that took Royal Navy crews minutes. Due to their clumsy handling, Spanish ships sailed too far apart to provide mutual support in battle.

Spanish ships were much better designed and built than Royal Navy ships, particularly the ships built in Havana in the West Indies, using local timbers, but they were badly maintained and fouling was not removed, reducing speeds to dangerous levels.

Royal Navy Press Gang 1780: ‘Moonlight Battle,’ Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War

The French admiral in Cadiz commented that the fastest ship in Langara’s squadron was slower than his slowest ship.

The Royal Navy was introducing the system of sheathing the bottoms of ships with copper, thereby preventing fouling and the consequent loss of speed. All of Rodney’s ships were ‘copper-bottomed’.

Wounds in Eighteenth Century naval fighting were terrible. Cannon balls ripped off limbs or, striking wooden decks and bulwarks, drove splinter fragments across the ship causing horrific wounds. Falling masts and rigging inflicted crush injuries. Sailors stationed aloft fell into the sea from collapsing masts and rigging, often to be drowned. Heavy losses were caused if a ship sank.

Naval ships’ crews of all nations were tough men. The British crews were better drilled than the Spanish, British guns firing three broadsides or more to every two fired by the Spanish.

Life on a warship, particularly the large ships of the line, was crowded and hard. Discipline was enforced with extreme violence, small infractions punished with public lashings. The food, far from good, deteriorated as ships spent time at sea. Drinking water was in constant short supply and usually brackish. Shortage of citrus fruit and fresh vegetables meant that scurvy easily and quickly set in. The great weight of guns and equipment and the necessity to climb rigging in adverse weather conditions frequently caused serious injury.

‘The Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Francis Holman: Rodney’s flagship HMS Sandwich is in the foreground with the Spanish ship San Domingo exploding behind Sandwich.

Background to the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780: The American Revolutionary War (or the American War of Independence) began in April 1775 as a war of revolt by the American colonists against British rule.

In 1779, France and Spain declared support for the new United States of America and joined the war against Great Britain. Both countries intended to take advantage of the difficulty Britain was experiencing in conducting the war on the far side of the Atlantic, to recover territories lost to Britain in the Seven Years War (1755 to 1763).

Spain intended to recover a number of islands in the Caribbean, lost to the British and, in the Mediterranean, the island of Minorca and the territory of Gibraltar.

Spanish troops and ships began a blockade of Gibraltar in July 1779.

The British garrison comprised some 5,000 troops with around 400 guns. Supplies of food began to run low towards the end of 1779.

The governor of Gibraltar, Lieutenant General George Eliott, was in regular contact with the government in London and kept them informed of his need for a re-supply.

On 1st October 1779, Admiral Sir George Rodney was appointed to command the Royal Navy Leeward Islands Station, in the West Indies. Rodney was to journey to his new appointment with four or five ships of the line, travelling down the coast of France, Spain and Portugal, before sailing to the south-west across the Atlantic to the West Indies.

The opportunity was taken for Rodney’s ships to escort the relief for Gibraltar and Minorca, as well as seeing the supply and merchant vessels bound for the West Indies past the hazardous French and Spanish coasts. A large convoy of over a hundred merchant vessels was assembled at Spithead, outside Portsmouth.

A section of the Royal Navy’s Channel Fleet was put under Rodney’s command for the voyage, giving Rodney twenty-two ships of the line, a 44-gun vessel and seven frigates. Squadrons within the fleet were commanded by Rear Admiral Sir John Lockhart-Ross and Rear Admiral Robert Digby.

The convoy moved down the Channel and sailed from Plymouth on 29th December 1779, after a considerable delay caused by the lack of preparedness of some of the Royal Navy vessels and adverse winds.

On 7th January 1780, Rodney’s fleet was three hundred miles west of Cape Finisterre, the north-western point of Spain, where the West Indies merchant vessels left the convoy to sail across the Atlantic. These ships were escorted by HMS Hector 74, Phoenix 44, Greyhound 44 and the cutter Tapageur.

At dawn on 8th January 1780, the British fleet caught sight of twenty-two Spanish ships to the north-east. The British appeared to have passed the Spanish during the night.

Rodney’s warships immediately gave chase to the Spanish and caught them in a few hours. The Spanish ships surrendered, with only token resistance and proved to be twelve ships loaded with provisions and three ships carrying powder and shot, stores for the Spanish fleet in Cadiz, escorted by seven Spanish warships: Guipuscoana 64, San Carlos 32, San Rafael 30, San Bruno 26, Santa Teresa 24, San Fermin 16 and San Vincente 14.

‘The Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Thomas Luny: San Domingo explodes.

The Guipuscoana was immediately taken into the Royal Navy as HMS Prince William, named in honour of Prince William, son of King George III, serving as midshipman on board HMS Sandwich, with the first lieutenant of HMS Sandwich as captain and a crew drafted from the other ships.

The twelve Spanish provision ships continued with the convoy, while the ammunition and stores ships were sent back to Britain, escorted by HMS America and Pearl.

Two further 74s, Dublin and Shrewsbury, were left at Lisbon for repairs, as Rodney’s fleet continued towards Gibraltar.

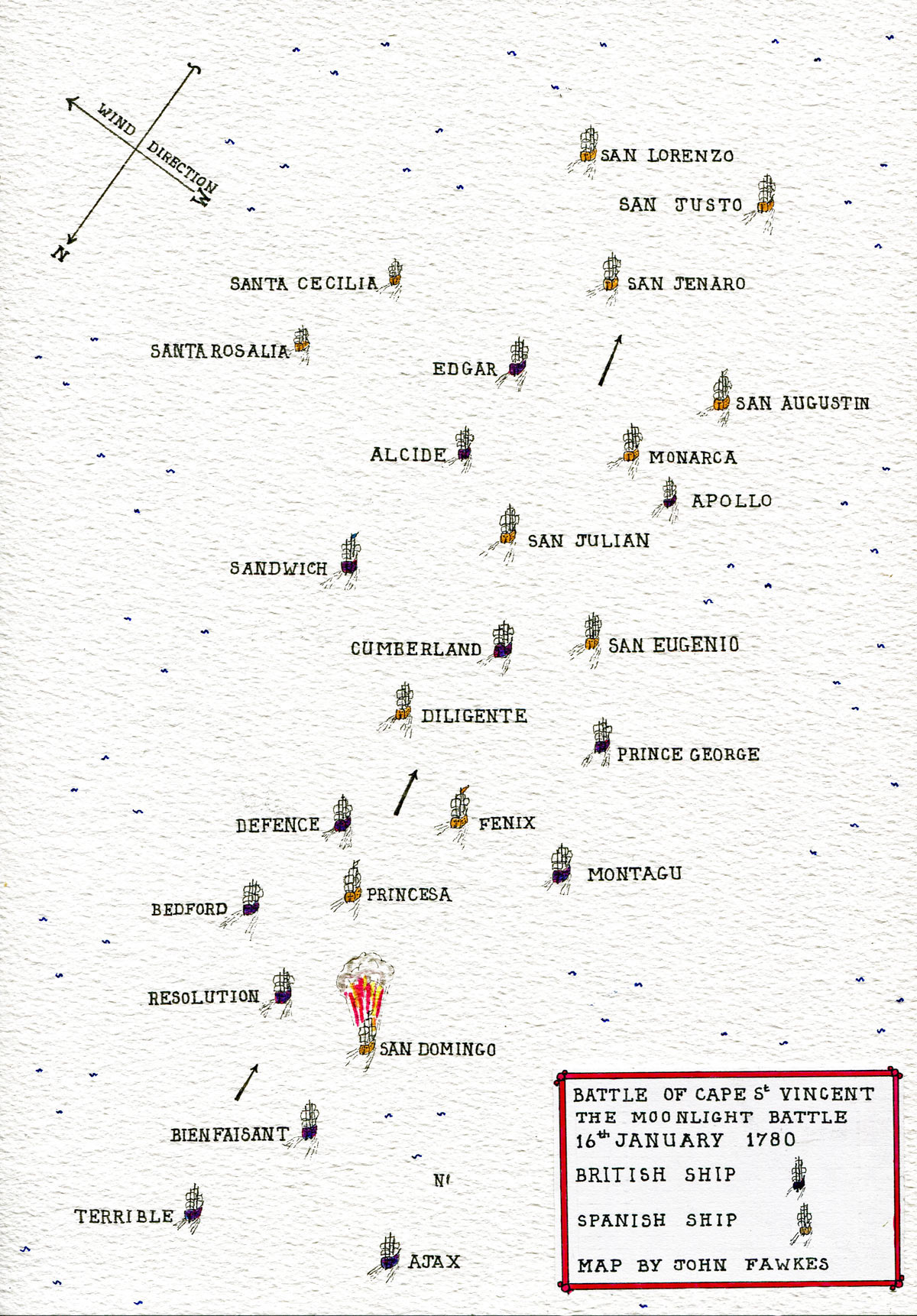

Map of ‘The Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780: Rodney received news from several merchant ships going north, that a Spanish squadron was sailing off Cape St Vincent, waiting to intercept the approaching British convoy. The British warships were warned to expect action.

Rodney’s fleet passed Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 and, at 1pm, the Spanish squadron was sighted to the south-east.

The Spanish ships were commanded by Admiral Don Juan de Langara and comprised nine ships of the line and two frigates.

Rodney ordered his ships into line abreast, advancing under a press of canvas.

Rodney was prone to gout and was at this time confined to his cot, from where he conducted the subsequent battle, acting through his flag captain.

The Spanish ships appeared to be offering battle and then tacked to starboard, heading in a southerly direction towards Cadiz. After initially believing his squadron to be facing a small Royal Navy escort for the large convoy of merchant ships, Langara realised that he was confronting a powerful Royal Naval force and turned to make for port.

At 2pm, Rodney changed his orders to ‘General Chase’, which gave his ships the discretion to break line and pursue the Spanish with as much speed as each ship could make.

As the Spanish were ‘breaking for home’ their ships quickly lost formation, as the faster ships outstripped the slower, leaving them at the mercy of the pursuing British.

As all the Royal Navy ships were faster than all the Spanish ships, it was a matter of time before disaster engulfed Langara’s squadron.

Rodney’s orders to his captains were to overtake the Spanish ships on the leeward side, thereby interposing between them and Cadiz, with the attack made ‘in rotation’. As each British ship came into action, the others were to pass and pursue the remaining Spaniards.

The general chase took place over a period of hours, leading to a battle that continued through the night. A substantial and increasing storm blew up, with heavy rain.

At 4pm, the leading British ships, HMS Bedford, Defence, Resolution and Edgar, made contact with the rear of the Spanish squadron. The approaching night was lit by a strong moon, giving the battle its characteristic nickname of the ‘Moonlight Battle’.

‘The Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Dominic Serres

Edgar fired a broadside into the first Spanish ship, San Domingo, as she forged past.

Marlborough and Ajax fired into San Domingo as they also passed her.

HMS Bienfaisant, came up behind, engaging San Domingo with her bow chasers, when the hallmark incident of the battle occurred. At 4.40pm San Domingo blew up, with the loss of her entire crew, bar one survivor.

Bienfaisant was fortunate in having her sails wet through from the driving rain, thereby saving her from catching fire from the flaming debris that rained down on her from the exploded San Domingo.

Ajax and Marlborough next came up with the Princesa, disabling her with broadsides, before resuming the chase of the remaining Spanish ships. Bedford continued the attack on Princesa for an hour, whereupon she surrendered at around 5.30pm to HMS Resolution.

At around 7.30pm, British ships overtook Langara’s flagship, Fenix. Fenix was attacked by Defence on her port side and Montagu on her starboard. The attack on Fenix was continued by Prince George, which brought down her mizzenmast and Bienfaisant, which brought down her main topmast. Fenix surrendered at 8.30pm.

Montagu meanwhile moved on to attack the Diligente, whose surrender was secured by a single broadside that brought down her main topmast.

As these British ships worked their way up the rear section of the Spanish squadron, other British ships overtook, to pursue the ships at the head.

HMS Cumberland caught up with San Eugenio and forced her to surrender at around 11pm, after shooting down all her masts. A boarding party could not be put aboard the San Eugenio until the next morning, due to the weather.

Battle at sea: ‘The Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by John Christian Schetky

Culloden and Prince George moved on to the San Julian and bombarded her into striking her colours at around 1am.

At the van of the Spanish fleet, the Monarca was attacked by HMS Alcide, but brought down the main topmast of the British ship. Monarca was then harried by the British frigate Apollo, until HMS Sandwich came up and put a heavy broadside into Monarca at 1am, causing her to strike her colours.

The Spanish ship San Augustin was compelled to surrender to the British HMS Monarch, but escaped into the night before she could be boarded. The two Spanish ships at the head of the fleet also managed to escape, with one other ship.

The next morning, the British ships worked away from the shore. Two of the surrendered Spanish ships were unable to do so and were wrecked on the rocks, San Julian and San Eugenio. The other surrendered Spanish ships were brought away from the coast and taken by British crews into Gibraltar, the Monarca, Diligente and Princesa, with the Spanish flagship Fenix.

Rodney gathered the convoy of merchant ships and led it on towards Gibraltar, where the strong winds blew most of the ships past Gibraltar into the Mediterranean.

The first inkling the Gibraltar garrison had of the imminent arrival of the relief fleet was when the Spanish in Algeciras flew signal flags indicating that ships were in sight. However, no Spanish ships took to sea. The first news of the battle reached Gibraltar on 16th January 1780 from a brig carrying flour.

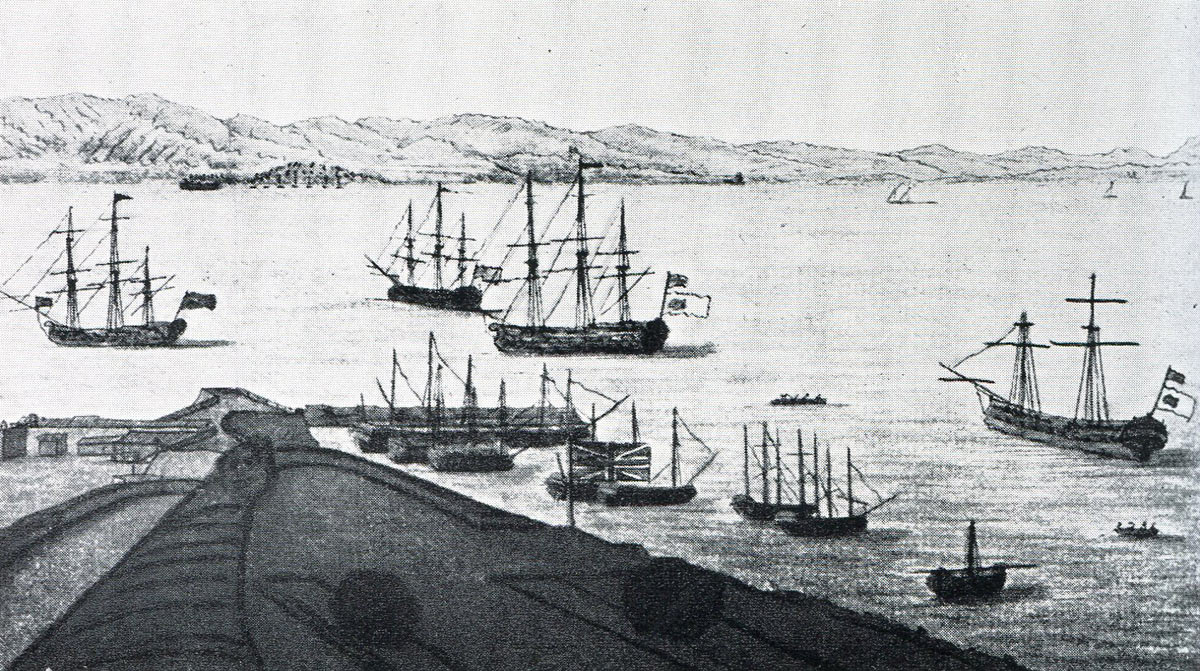

Rodney’s fleet approaching Gibraltar after ‘The Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Dominic Serres

A second brig arrived in the evening, bringing specific news of Rodney’s victory over Langara’s Spanish squadron.

Despite the stormy weather and the strong westerly wind, the frigate HMS Apollo came into Gibraltar, followed by the captured Spanish flagship Fenix and the other warships of the fleet.

Over the following days, the merchant ships blown on into the Mediterranean were brought back to Gibraltar and the garrison re-supplied.

Casualties at the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780:

British casualties were 141 killed and wounded.

Spanish casualties were unknown but probably in the region of 5,000 killed and wounded. Several hundred were taken prisoner, including Admiral Langara and other officers. The sailors were exchanged and the officers released against their parole.

Follow-up to the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780:

Rodney arrived in Gibraltar on 26th January 1780 in HMS Sandwich.

The store ships bound for Minorca were dispatched under escort, while the main part of the convoy unloaded in Gibraltar.

The four captured Spanish ships were taken into the Royal Navy under their original names, except for the Fenix, renamed HMS Gibraltar.

HMS Edgar remained in the Gibraltar squadron, a change of station which brought criticism on Rodney from the Admiralty and a direction that Edgar was to return to the Channel Fleet at the first opportunity.

Rodney’s fleet finally sailed from Gibraltar on 13th February 1780. Rodney headed west-south-west, across the Atlantic for the West Indies, while the warships from the Channel Fleet escorted the merchant ships back to Britain.

Eliott seized the opportunity to rid the Gibraltar garrison of many of the remaining families of the soldiers who were unable to support themselves. They were shipped back to Britain in the now empty supply ships.

Rodney’s final support to Eliott was to supply the garrison with a substantial consignment of gunpowder and shot from the captured Spanish ships.

Rodney’s fleet in Gibraltar after ‘the Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Dominic Serres

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780:

- The news of Rodney’s victory over the Spanish was well received in Britain, after the succession of failures in the American War. A salute was fired from the Tower of London. Rodney was thanked by both Houses of Parliament and awarded a substantial pension.

- The success of the battle lay in seizing the opportunity to attack the fleeing Spanish squadron, despite the onset of night and worsening weather conditions and the knowledge that the Spanish squadron was fleeing towards Cadiz, where a fleet of twenty Spanish and four French ships of the line were waiting.

Rodney’s ships lie off the New Mole in Gibraltar after the ‘Moonlight Battle’ at Cape St Vincent on 16th January 1780 in the American Revolutionary War: the ship on the right and in the centre are captured Spanish ships with British colours over Spanish colours: eye witness sketch by Captain John Spilsbury

- The Cadiz fleet made no effort to interfere with Rodney’s fleet of warships and merchantmen while they were in Gibraltar and re-supplying Minorca.

- The Admiralty wrote to Admiral Rodney saying ‘You have taken more line-of-battle ships than had been captured in any one action in either of the two last preceding wars’.

- Rodney commented in a letter to his wife that the captured Spanish ships were much superior in design and construction to the British ships, other than the addition of copper sheeting to the bottoms of the British ships.

- Serving on HMS Prince George was the son of King George III, Prince William. Prince William was rated midshipman after the battle.

- The Spanish commander, Admiral Don Juan de Langara, wounded in the battle, was treated with great consideration and shown around the fleet and the garrison. He was surprised at the end of a visit to HMS Prince George when he was informed by Prince William, acting as a midshipman, that his boat was ready to take him ashore. Royal princes did not act in a menial capacity in Spain.

- During his stay on Gibraltar, Prince William was given a tour of the defences by Colonel Green, the chief engineer of the garrison.

- After the ‘Moonlight Battle’, Captain McBride of HMS Bienfaisant presented Prince William with Admiral Langara’s personal ensign, taken from the captured Spanish flagship Fenix. Prince William in turn presented the flag to his father, King George III.

- A Highland regiment, the 73rd, was on board the convoy, bound for the Minorca garrison. As Rodney had posted soldiers from the regiment as marines on board his ships, left short-handed by the need to crew the Spanish ships taken off Cape Finisterre, the regiment was landed at Gibraltar to be re-embarked on board the troopships. General Eliott, the governor of Gibraltar, seized the opportunity to retain the 73rd for his own garrison.

- On his subsequent voyage to the West Indies, Rodney’s squadron fell in with fifteen French supply vessels heading for the French possession of Ile de France in the Indian Ocean, escorted by two 64-gun ships of the line. Three of the supply ships and the 64-gun Protée were captured by Rodney.

References for the Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780:

The Siege of Gibraltar by McGuffie

The Royal Navy a History by Clowes Volume III

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Great Siege of Gibraltar

The next battle of the Napoleonic Wars is the Storming of Seringapatam

To the American Revolutionary War index