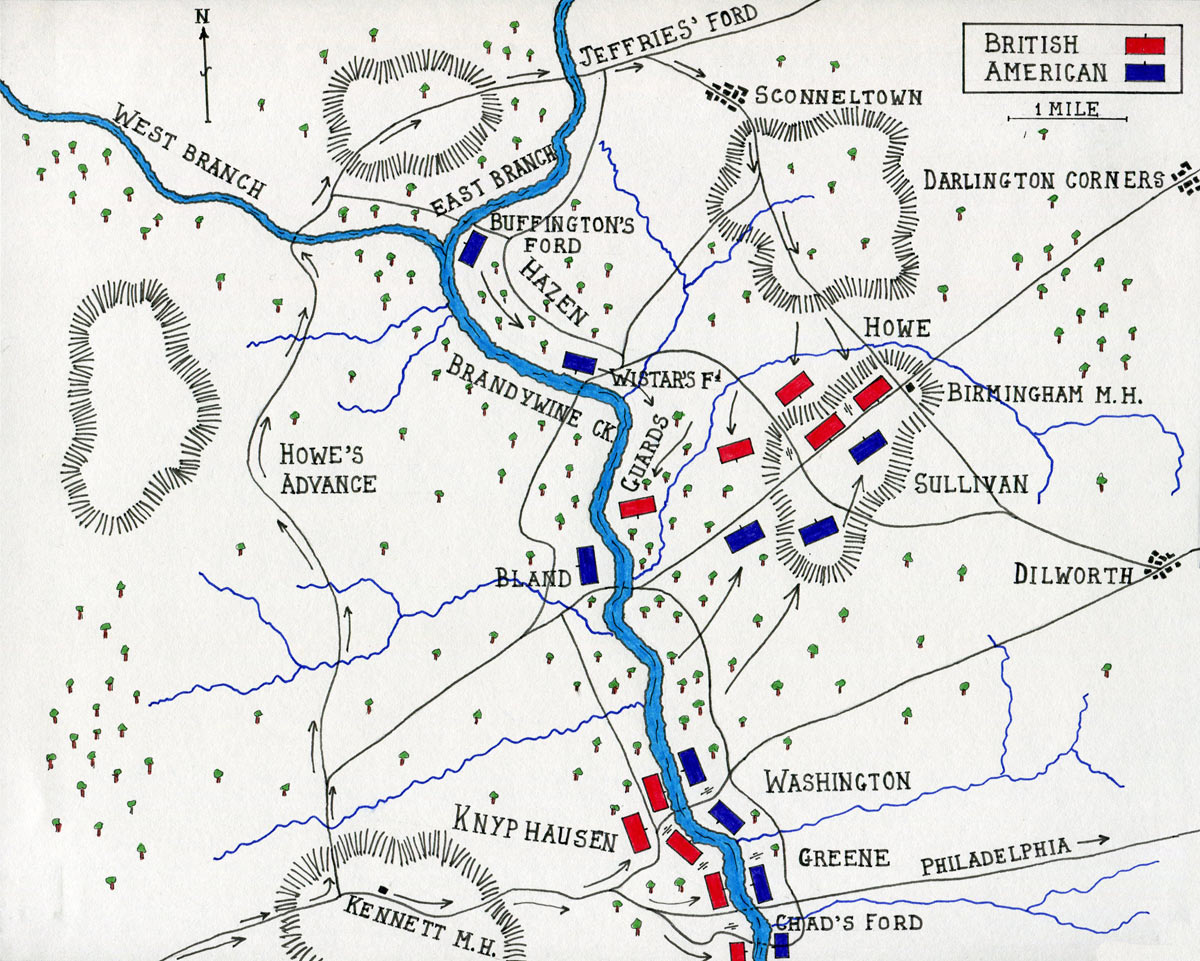

Major-General Sir William Howe’s outflanking of General Washington’s position on 11th September 1777 in the British advance to take Philadelphia

General George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette at the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by John Vanderlyn

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Bennington

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Freeman’s Farm

To the American Revolutionary War index

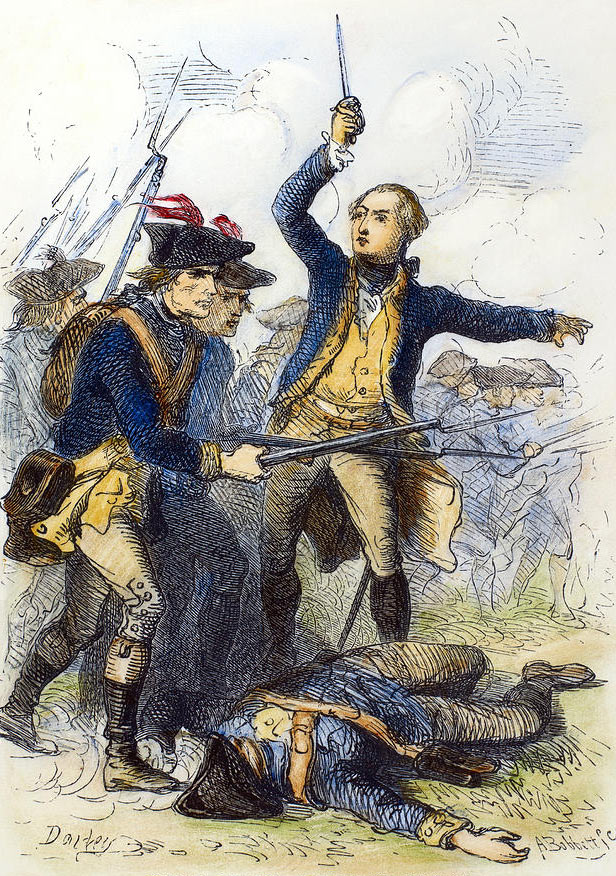

General Washington rallying American troops at the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

Battle: Brandywine Creek

War: American Revolution

Date of the Battle of Brandywine Creek: 11th September 1777

Place of the Battle of Brandywine Creek: Pennsylvania, west of Philadelphia.

Combatants at the Battle of Brandywine Creek: British and Hessian troops against the American Continental Army and Militia.

Major-General Sir William Howe: British, British commander at the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

Generals at the Battle of Brandywine Creek: Major-General Sir William Howe and General George Washington.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Brandywine Creek: Around 6,000 British and Hessians against 8,000 Americans.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Brandywine Creek:

The British wore red coats, with bearskin caps for the grenadiers, tricorne hats for the battalion companies and caps for the light infantry. The Highland Scots troops wore the kilt and feather bonnet.

The two regiments of light dragoons serving in America, the 16th and 17th, wore red coats and crested leather helmets.

The Hessian infantry wore blue coats and retained the Prussian style grenadier mitre cap with brass front plate.

The Americans dressed as best they could. Increasingly as the war progressed infantry regiments of the Continental Army mostly took to wearing blue uniform coats. The American militia continued in rough clothing.

Soldier and Officer of the 27th Regiment of Foot: Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

Both sides were armed with muskets. The British and German infantry carried bayonets, which were in short supply among the American troops. The Highland Scots troops carried broadswords. Many men in the Pennsylvania regiments carried rifled weapons, as did other backwoodsmen. Both sides were supported by artillery.

Winner of the Battle of Brandywine Creek: The British and Hessians were left occupying the battlefield, after driving the Americans from their position on Brandywine Creek.

British Regiments at the Battle of Brandywine Creek:

16th Light Dragoons

Two Composite battalions each of grenadiers, light infantry and Foot Guards (1st, 2nd and 3rd Guards)

4th, 5th, 10th, 15th, 17th, 23rd (Royal Welsh Fusiliers), 27th, 28th, 33rd, 37th, 40th, 44th, 46th, 49th, 55th, 64th Regiments of Foot and three battalions of Fraser’s Highlanders or 71st Foot.

British Light Dragoon: Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

American Units at the Battle of Brandywine Creek:

Wayne’s Pennsylvania Brigade, Weeden’s Virginia Brigade, Muhlenburg’s Virginia Brigade, Proctor’s Artillery, Delaware Regiment, Hazen’s Canadian Regiment, Maxwell’s Light Infantry, Colonel Bland’s 1st Dragoons, Pennsylvania Militia, De Borre’s Brigade, Stephen’s Division and Stirling’s Division

Background to the Battle of Brandywine Creek:

The British plan for 1777 was that Major-General Burgoyne would bring his army, comprising British, Hessian, Brunswick and Canadian troops with a strong contingent of Native Americans and Loyalist Americans, south by Lake Champlain and the Hudson River, while Major-General Sir William Howe made his way north up the Hudson River to meet him.

Howe and his senior officers decided that it would be a more effective use of the British New York based army to move it by sea to the Chesapeake Bay and capture the colonist’s capital, Philadelphia.

American battery firing on British Foot Guards as the British begin their attack on General Sullivan’s Division at the Birmingham Friends Meeting House: Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Lord Cantelupe who was present at the battle as an officer of the Coldstream Guards

Howe wrote to Burgoyne informing him of this change of plan. Burgoyne’s army was left to fight its way south on its own, with disastrous consequences for the British cause.

American troops advancing at the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

Major-General Sir William Howe’s British and Hessian army was transported by the Royal Navy to Chesapeake Bay and began its march towards Philadelphia.

General George Washington marched his army of American Continental Regiments and Colonial Militia south to Wilmington and attempted to delay the capture of Philadelphia, falling back before the British and Hessian army.

Map of the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Brandywine Creek:

On 9th September 1777, Washington’s army took position along the east bank of the Brandywine Creek at Chad’s Ford (now Chadds Ford).

Brandywine Creek flowed through undulating countryside and heavily wooded hills, with steep cliffs along its banks in places. Below Chad’s Ford, the creek became narrower and faster so as to be unfordable.

American 2nd Canadian Continental Regiment: Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

The route to Philadelphia crossed Brandywine Creek at Chad’s Ford, the most southern of a series of fords. Above Chad’s Ford, other fords crossed the creek up to the point where it divided into east and west branches.

Washington expected Howe’s army to march from Kennett Square, in the West, up to Chad’s Ford and carry out a frontal assault.

Pennsylvania Militia were posted to the left of the Chad’s Ford position, where little threat was perceived. Washington positioned Wayne’s Pennsylvania Continentals, with Weedon’s and Mulenburg’s brigades, in the centre opposite Chad’s Ford, under the command of Major-General Nathaniel Greene.

Major-General John Sullivan commanded on the right of the American army, posting forces under Colonel Moses Hazen at the distant Wistar’s and Buffington’s Fords. Light infantry and piquets were posted to the West of Brandywine Creek, to give warning of the British advance.

During the morning of 11th September 1777, Major-General Howe’s army arrived at Kennett Meeting House to the West of Chad’s Ford. There his army divided. The Hessian, Lieutenant-General Knyphausen, led a powerful force on down the road towards Chad’s Ford.

At around noon on 11th September, Knyphausen’s force reached the Brandywine Creek at Chad’s Ford. His troops comprised Major Patrick Ferguson’s Riflemen and the Queen’s Rangers, followed by two British brigades (4th, 5th, 23rd, 49th, 10th, 27th, 28th, 40th Foot and three battalions of Fraser’s 71st Highlanders) and a Hessian brigade, also a squadron of 16th Light Dragoons and guns.

Knyphausen’s battalions took positions along the hills on the west bank and he began to cannonade the Americans across the river.

In the meantime, the second British column, under Major-General Howe and Major General Lord Cornwallis, marched north from the Kennett Meeting House, to cross the Brandywine Creek some miles upstream of the Chad’s Ford position.

Howe and Cornwallis continued north, until they reached a crossing point that the Americans were not occupying. This proved to be a ford on the West Branch of Brandywine Creek and Jeffrey’s Ford on the East Branch. After crossing both branches of the Brandywine Creek, the British turned south, marched through Sconneltown and reached the Birmingham Meeting House, behind Hazen’s troops and threatening the right rear of Washington’s main army.

British Foot Guards resting during the advance to outflank General Washington’s American Army at the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

The final stage of Howe’s and Cornwallis’ advance would be to pass Washington’s right flank and cut his army off from Philadelphia.

Birmingham Meeting House: Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

Washington appears to have been advised of the British encircling movement by Hazen’s distant troops, but to have discounted the warning for some hours. Washington and his staff were convinced that the main attack was to be a frontal assault over Chad’s Ford. It was not until early afternoon that he was finally persuaded that the main British movement was to his right rear. During that time, he began an assault across the ford, but withdrew it.

On the alarm being given, Sullivan marched his right wing of the American army to the North-East and, joining the retreating Hazen, formed his troops on a hill at the Birmingham Meeting House. Howe’s regiments formed three columns and attacked the Americans.

British 46th Foot attacking at the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

Finally convinced of his mistake by the sound of heavy firing, Washington dispatched Greene with the American reserve to support Sullivan. By that time the British attack had driven Sullivan’s troops off the hill and Greene and Sullivan were retreating from the field.

At Chad’s Ford, Knyphausen launched an assault across the river, led by the 4th and 5th Foot. A contingent of British Foot Guards and grenadiers from Howe’s force emerged from the forest, where it had been temporarily lost, and attacked the right flank of Washington’s troops at the ford. The Americans were driven from their positions.

American troops at the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Frederick Coffay Yohn

The battle ended with the American army withdrawing up the road to Philadelphia in considerable confusion. Nightfall saved the Americans from greater loss.

The British encamped on the battlefield.

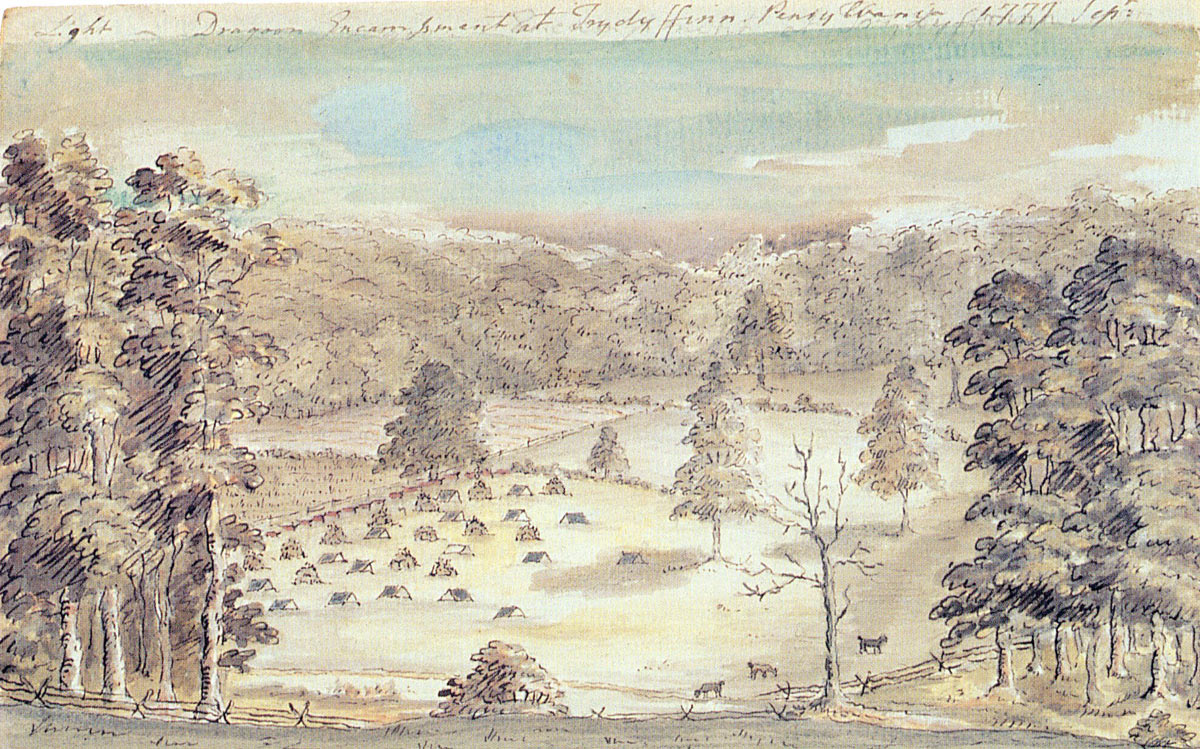

Camp of the 16th Light Dragoons the night after the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Lord Cantelupe, present at the battle as an officer of the Coldstream Guards

Casualties at the Battle of Brandywine Creek:

The British suffered casualties of 550 killed and wounded.

The Americans suffered casualties of around 1,000 killed, wounded and captured and lost 11 guns, 2 of which had been taken at the Battle of Trenton.

Follow-up to the Battle of Brandywine Creek: Brandywine hastened the loss of Philadelphia to the British. Washington was intending only to delay the British advance rather than halt it.

Brandywine is not considered a decisive battle, particularly in the light of the disaster about to engulf Burgoyne’s British and German Army on the Hudson River.

Wounding of the Marquis de Lafayette at the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Charles Henry Jeans

Anecdotes from the Battle of Brandywine Creek:

Light Company Man 4th King’s Own Royal Regiment of Foot: Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

- During the course of the Battle of Brandywine, the British officer, Major Patrick Ferguson, was lying in undergrowth with his company of light infantrymen, armed with Ferguson breech loading rifles, when two mounted American officers came into sight. Ferguson’s men asked if they should shoot them. Ferguson took the view, widely held in the British and other European armies, that to ‘snipe’ individual officers amounted to murder and ordered his men not to fire on the two officers. After the battle, Ferguson learnt that the two American officers were probably General George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette.

- The Battle of Brandywine is a striking example of outmanoeuvring a river position by the expedient of marching an outflanking force along the river, until it finds an undefended crossing point, crossing the river there, and marching back behind the position under attack, while the opposition is ‘fixed’ by a demonstrating force, sufficiently large and vigorous to deceive the defending general into believing that it is the main attack.

- During the Battle of Brandywine, the British 15th Regiment of Foot ran out of ball ammunition. The soldiers continued fighting by ‘snapping’ their muskets, or firing with a charge of black powder, to give the impression they were still able to shoot, while more ball was brought up. The regiment took the nickname of ‘the Snappers’. The standard issue for British troops armed with the ‘Brown Bess’ musket was 24 rounds. These rounds were quickly fired in heavy fighting. Systems for re-supplying infantry were haphazard and many regiments, both British and American, found themselves without ammunition during the course of a battle.

- ‘Spring up’ was the command for the British Light Infantry to stand up from the prone firing position. The 10th Regiment of Foot acquired the nickname ‘the Springers’ from this command.

-

Marquis de Lafayette wounded at the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 in the American Revolutionary War

The Marquis of Lafayette, a French nobleman, went to America at the age of 19 years at the beginning of the American Revolutionary War. Lafayette was a close associate and staff officer to General George Washington. Lafayette, wounded at the Battle of Brandywine Creek fighting with Sullivan, became a symbol of French assistance to the Americans, and fought through the Revolutionary War, playing an important part at the Battle of Yorktown, which brought the war to an end.

References for the Battle of Brandywine Creek:

History of the British Army by Sir John Fortescue

The War of the Revolution by Christopher Ward

The American Revolution by Brendan Morrissey

The Philadelphia Campaign Volume I Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia by Thomas J. McGuire

The previous battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Bennington

The next battle of the American Revolutionary War is the Battle of Freeman’s Farm

To the American Revolutionary War index