Battles of the War of the American Revolution 1775 to 1783:

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Introduction (below):

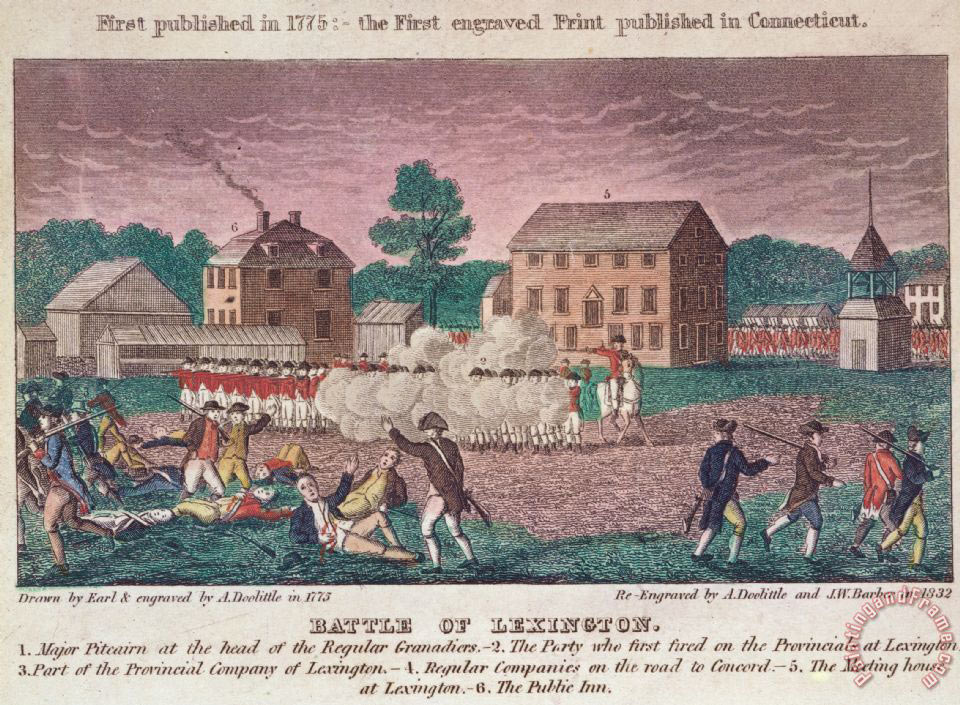

Battle of Lexington and Concord: The opening shots of the American Revolutionary War on 19th April 1775, that ‘echoed around the world’.

Battle of Bunker Hill: The British ‘Pyrrhic Victory’ on 17th June 1775 in the opening weeks of the American Revolutionary War.

Battle of Quebec 1775: The unsuccessful American invasion of Canada and attack on Quebec on 31st December 1775.

Battle of Sullivan’s Island: The successful defence of Fort Sullivan on 28th June 1776 by Charleston’s recruit artillerymen against a powerful Royal Navy squadron.

Battle of Long Island: The disastrous defeat of the Americans on 27th August 1776 leading to the loss of New York and the retreat to the Delaware River.

Battle of Harlem Heights: The skirmish on 16th September 1776 in northern New York island that restored the confidence of the American troops.

Battle of White Plains: The battle on 28th October 1776, leading to the American withdrawal to the Delaware River and the capture of Fort Washington by the British.

Battle of Fort Washington: The battle on 16th November 1776 that saw the American army forced off Manhattan Island and compelled to retreat to the Delaware River.

Battle of Trenton: George Washington’s iconic victory on 26th December 1776 over Colonel Rahl’s Hessian troops after crossing the frozen Delaware River; the battle that re-invigorated the American Revolution.

Battle of Princeton: The sequel on 3rd January 1777 to the successful Battle of Trenton: the two battles began the resurgence of the fortunes of the American Colonists in the Revolutionary War.

Battle of Ticonderoga 1777: The humiliating American abandonment of Fort Ticonderoga on 6th July 1777 to General Burgoyne’s British army.

Battle of Hubbardton: The hard-fought battle on 7th July 1777 in the forest south-east of Fort Ticonderoga.

Battle of Bennington: The battle fought on 16th August 1777 that did much to raise the morale of the American colonists and made Brigadier Stark an American hero.

Battle of Brandywine Creek: Major-General Sir William Howe’s outflanking of General Washington’s position on 11th September 1777 in the British advance to take Philadelphia.

Battle of Freeman’s Farm: The Battle fought on 19th September 1777 General Burgoyne had to win decisively but failed to do so.

Battle of Paoli: The surprise night attack on 20th/21st September 1777 by the British on the camp of General ‘Mad Anthony’ Wayne’s Pennsylvanians: also known as the ‘Paoli Massacre’.

Battle of Germantown: General George Washington’s unsuccessful attempt on 4th October 1777 to retake Philadelphia; the battle that helped convince the French and Spanish the American cause was worth supporting with military and naval intervention against Britain.

Battle of Saratoga: The surrender of General Burgoyne’s British Army to the American Colonists on 17th October 1777, bringing France and Spain into the war.

Battle of Monmouth: The battle fought on 28th June 1778 by the American Continental Army against the British, after the 1777/8 winter spent training under Steuben.

Siege of Savannah: The unsuccessful attempt by the Americans and the French to re-take Savannah, Georgia, on 9th October 1779.

Siege of Charleston: The siege and capture of Charleston, capital of South Carolina, by the British on 12th May 1780.

Battle of Camden: The British victory on 16th August 1780 over General Horatio Gates in North Carolina.

Battle of King’s Mountain: The savage ‘All American’ battle on 7th October 1780, where the only Englishman present was the loyalist commander, Major Patrick Ferguson.

Battle of Cowpens: Daniel Morgan’s victory over the notorious Tarleton on 17th January 1781.

Battle of Guilford Courthouse: Cornwallis’s Pyrrhic victory over Nathaniel Green in the North Carolina countryside on 15th March 1781.

Battle of Yorktown: General George Washington’s resounding victory and the surrender of Lord Cornwallis’s British army on 19th October 1781; the end for Britain in the American Colonies.

Siege of Gibraltar: The siege of Gibraltar, between 8th July 1779 and 2nd February 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War: Podcast of The Great Siege of Gibraltar.

Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780: ‘The Moonlight Battle’: Admiral Sir George Rodney’s decisive naval victory on 16th January 1780 over a Spanish Fleet, that enabled Rodney to re-supply Gibraltar.

Introduction:

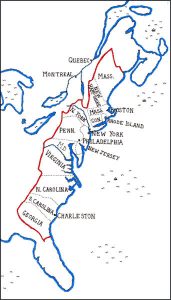

On the outbreak of the war, the American colonies were, from North to South; New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut (making up New England), New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

The principal cities were Boston in Massachusetts, New York, Philadelphia, the colonial capital of Pennsylvania, and Charleston, the capital of South Carolina.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

To the North of the colonies, lay the British province of Canada, with its mainly French speaking population, and to the West the hinterland of the American landmass.

The American colonies differed widely. The New England colonies were established and settled largely by English Presbyterians and comprised small close knit farming communities, with fishing and trading centres along the coast. The populations were inward looking and intolerant of outsiders.

Boston was a busy port, reputed to be one of the wealthiest in the English speaking world.

New York contained a polyglot population of Dutch, Swedes and English. Upstate New York contained large estates. The Hudson River, a main communications artery, was the centre of considerable trading activity. The large state area contained a substantial Indian presence from the Iroquois Six Nations confederation, particularly the Mohawks.

Pennsylvania, established by the Quaker Penn family, had been hamstrung in the early part of the 18th Century by the stranglehold the Quakers maintained on government. The population, particularly in the West of the colony, was largely German and Scotch-Irish with little commitment to the British Crown. The colony was a prosperous community of small farmers. In the East lay Philadelphia, the largest city in the American colonies and the first capital of the United States.

Massachusetts militia, ‘the Minutemen’, turning out to oppose the British march to Concord on 19th April 1775 at the beginning of the American Revolutionary War

Virginia and the southern colonies were different in character. Tobacco growing along the ‘Tideway’ coastline was the backbone of the Virginian economy. Ships from England collected the tobacco and delivered, in exchange, goods that enabled the most successful planters to maintain the lavish lifestyle of English country gentlemen. More than fifty per cent of the colony’s population comprised African slaves. In the remote western regions of the colony, colonists cut farmsteads from the forests and maintained a precarious existence, in the face of resistance from the native American tribes.

The Carolinas and Georgia, the most recently established colonies, were similar in character and outlook to Virginia.

The relationship between the American colonies and the British Crown was complex and turbulent. In each colony, the Royal Governor had historically been at odds with the Assembly of elected leading colonials, usually over taxation. Pennsylvania, where the Penn family exempted themselves from financial contribution to the running of the colony, was an example of the almost unworkable system that had grown up.

The main element that kept the colonies and the British Crown in uneasy alliance was the threat from France, with its powerful base along the St Lawrence seaway in Canada and along the western borders of New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia.

The long and agonising French and Indian War between 1755 and 1762 saw the French forced out of Canada, with Britain assuming government of the French population, and the American colonies released from the threat of French invasion and dominance.

The Seven Years War, fought in Europe, India and the West Indies, left Britain with considerable debt. The British government considered the American colonies should contribute to the reduction of that debt and many of the measures that brought about the Revolutionary War were to that end.

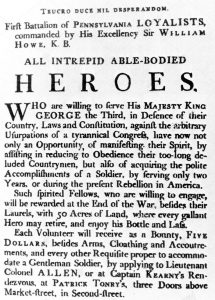

Following the French and Indian War, a substantial British garrison remained in America. 18th Century armies were not easy guests, particularly with their practices of enforced and fraudulent recruitment. The redcoats became as unpopular in the towns and villages of New England as they were in ‘Old’ England. The relationship between the royal troops and their provincial colleagues in the war against the French had been far from easy. The royal officers tended to be contemptuous of the professionalism of the provincials and the colonies resented the loss of life in battles like Ticonderoga, brought about by the incompetence of royal officers. A dispute that simmered throughout the French and Indian War arose from the ranking of provincial officers beneath royal officers. George Washington found this particularly galling.

General Braddock’s disastrous defeat in July 1755 in Western Pennsylvania was a major blow for the prestige of the British Crown. The withdrawal of Colonel Dunbar with the survivors of Braddock’s regular troops to Philadelphia in the summer of 1755, leaving Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and Western New York to be ravaged by Indian raiding parties, encouraged by the French, led many in the colonies to question the worth of the link with Britain and to look to their own colonial governments to fill the vacuum left by the royal forces.

The corruption that underlaid the Braddock expedition (see Braddock 1, Braddock 2 and Braddock 11) must have been all too apparent to those involved in it and affected by it.

Braddock’s campaign was a looming portent for the future of the colonies. Many of the participants went on to take major parts in the Revolutionary War: George Washington, Gage, Gates, Mercer, Lee and several others.

The War:

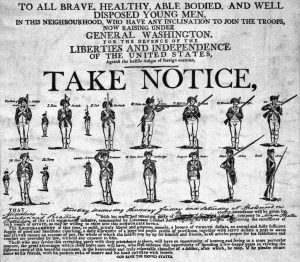

In 1775, Major General Gage (a veteran of Braddock’s campaign) was the Commander-in-Chief in Boston. He commanded eleven battalions of foot in Boston, one in New York and six others spread through North America; 7,000 men in all.

Gage knew war was coming. Magistrates loyal to the British Crown were being displaced in many parts of New England. In February 1775, a Provincial Congress met in Cambridge and took over the government of Massachusetts, other than Boston itself. The colonial militia was arming and drilling. Gage called for substantial re-inforcements from Britain.

The British army of the time was not an efficient institution. Following the French and Indian War, Parliament reduced the number of regiments.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Recruiting was always a problem, particularly for the regiments in America. There was no formal military education for officers and efficiency varied widely between regiments. In peace time there was little training and, in a garrison like Boston, where the surrounding countryside was hostile, the opportunities for field days, even if the officers were inclined to conduct them, were limited.

‘Boston Massacre’: British troops confront and fire on a crowd in Boston on 5th March 1770: American Revolutionary War

If the British infantry had been moderately competent and led with a modicum of professionalism, the attack on the position at Breed’s Hill, in the Battle of Bunker Hill, would have been successful within minutes. The illustration of the battle, showing superbly turned out redcoats in serried ranks is misleading. The failure of the British artillery to take the correct calibre of ammunition into the battle is a better indicator of the army’s efficiency.

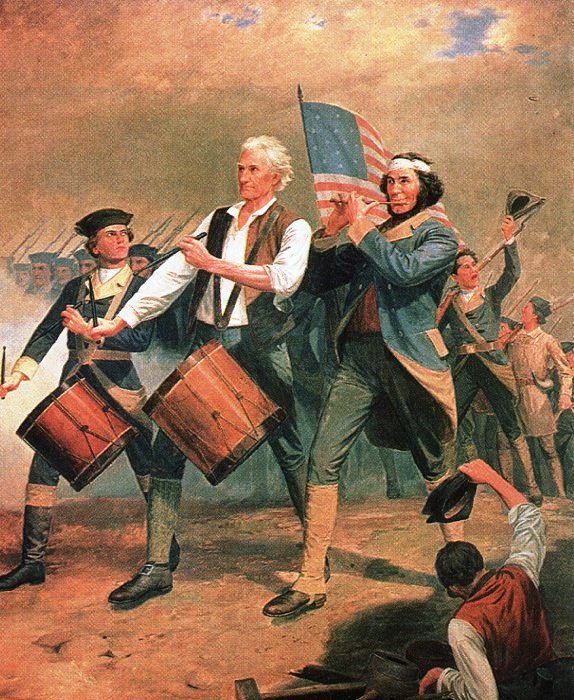

The competence of both sides improved out of recognition as the war progressed. The crossing of the Delaware in mid-winter at the Battle of Trenton by the American troops, many without shoes, and the resistance of the 40th Foot in Chew’s House at the Battle of Germantown are examples of inspiring conduct in battle on each side.

Concord:

The war began with the attempt by Gage to seize the armaments held by Congress at Concord and the exchange of shots at Lexington.

Following the success of the running fight that saw the British hurrying back to Boston, the New England militia invested the city, building entrenchments along the west bank of the bay.

Battle of Bunker Hill on 17th June 1775 in the American Revolutionary War: picture by Richard Simkin

In June 1775 American forces occupied Breed’s Hill on the Charlestown peninsular opposite Boston and built a redoubt. On 17th June 1775 the British landed and after the bloody Battle of Bunker Hill drove the Americans back to the mainland.

The siege of Boston continued, with the British situation deteriorating, until 17th March 1776 when the force, now commanded by General Howe, evacuated Boston and sailed for Halifax in Nova Scotia, leaving Boston to the American Congressional Army commanded by General George Washington.

Attempts had been made to put the British Army on some sort of war footing, but with limited success. The only new regiment raised was Fraser’s 71st Highlanders, comprising two battalions. Five existing regiments of foot were sent to America and five more with the 16th Light Dragoons were preparing to embark.

While the siege of Boston was in progress in 1775, Brigadier Montgomery, an inspiring officer with service in the British Army, with the mercurial Brigadier Benedict Arnold, led an audacious and nearly successful American attack on Canada. Only the vigour and resourcefulness of the Governor, Guy Carleton, ensured that the assaults on Quebec on the night of New Year’s Eve 1775 were repelled, with the death of Montgomery.

In May 1776 Major General Lord Cornwallis arrived off Charleston and with Major General Clinton attempted to take the capital of South Carolina, but without success. In July 1776 the British force sailed north, rejoining Howe on Staten Island, off New York.

In August 1776 Howe began his inexorable advance against the Americans, fighting the battles of Long Island, Harlem Heights, White Plains and capturing Fort Washington and Fort Lee. General Washington fell back from position to position until by the end of the year he lay to the West of the Delaware River. The Americans were at a low ebb, the confidence of the troops severely shaken.

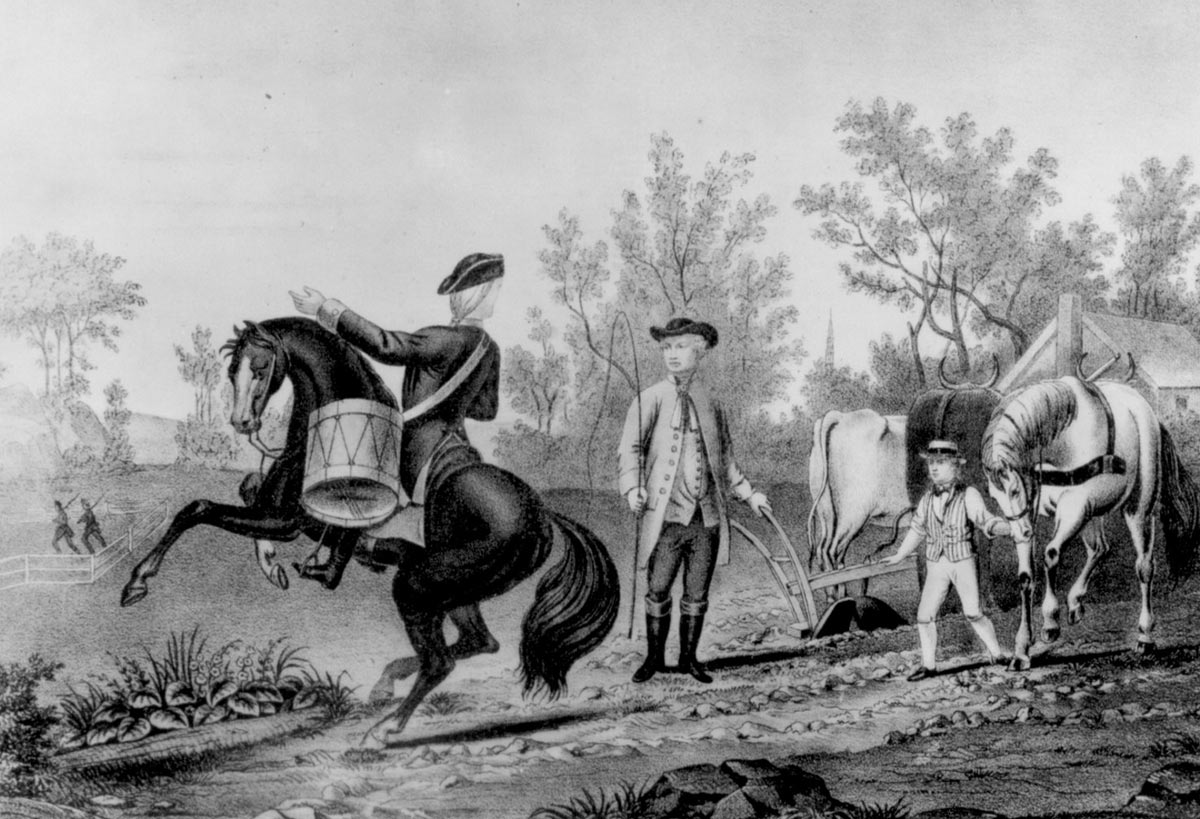

There was however an underlying dynamic to the war. Each British victory could only, at best, put off the inevitable. A single American triumph and sometimes even a failure reversed the impact of a string of British successes.

General Israel Putnam called from his plough to the service of his country: an image reminiscent of the incident in classical history; Cincinnatus summoned from his ploughing to be Dictator of Rome, against the threat from the Aequians

Such a triumph was the Battle of Trenton on 26th December 1776 when General Washington launched a surprise attack across the Delaware and captured a substantial Hessian force under Colonel Rahl. At the news of Rahl’s defeat and death General Lord Cornwallis turned back from his return to England to cope with the reverse. The American war effort was galvanised.

In 1777 the British Government approved General Howe’s plan for an attack on Philadelphia. In addition Lord Germaine, the British minister directing the war, ordered Major General Burgoyne to lead an attack from Canada down the Crown Point-Ticonderoga route to the Hudson and into New York. At a stroke Germaine ensured that the British achieved the feat that had eluded George Washington; the mass mobilisation of the New England militia.

Burgoyne, with the assistance of able officers such as Brigadier Simon Fraser and Colonel St Leger, in August 1777 moved south against the increasing quagmire of local resistance until, running out of supplies, he was forced to surrender at the Battle of Saratoga on 17th October 1777.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

The American commander was Major General Horatio Gates, another veteran of Braddock’s, but the true inspiration for the American success was Benedict Arnold.

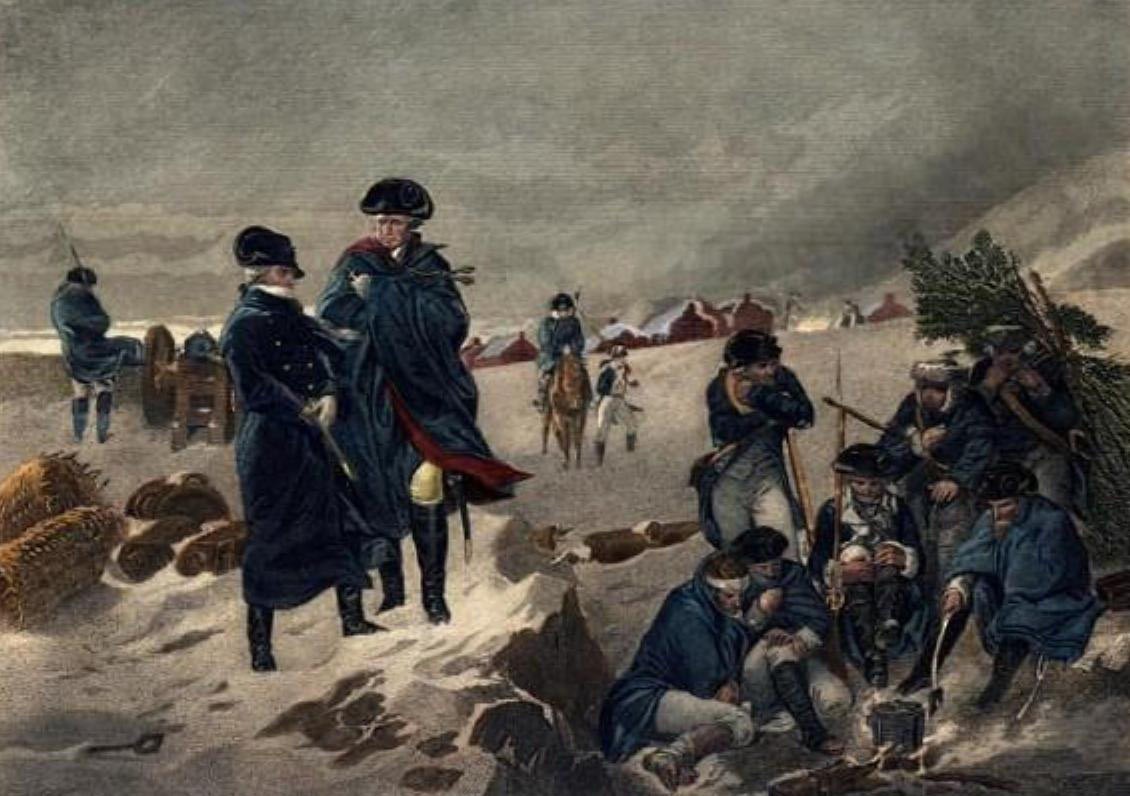

Major General Steuben training the American Regiments of Foot at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777/1778: picture by E.A. Abbey

Meanwhile further south General Howe landed at Wilmington in August 1777 and advanced against General Washington. Following the Battle of Brandywine Creek on 11th September 1777 the British took Philadelphia and Washington settled in for the winter in Valley Forge to the North of the city, making his last effort of the year in the attack at the Battle of Germantown.

It was in Philadelphia that the British received the news of the capture of Burgoyne’s army. The Battle of Trenton caused the first crack. The Battle of Saratoga began the splintering. France, licking her wounds after her territorial losses in the Seven Years War, and Spain, keen to renew the attempt to recover Gibraltar, actively planned to join the war against Britain. The creaking British war machine was incapable of replacing the losses from Burgoyne’s capitulation.

In March 1778 Major General Clinton succeeded Howe as British commander in America. On 8th July 1778 the French Toulon Fleet arrived off the Delaware River.

By the end of 1778 Clinton held New York, watched by General Washington from the main land, neither side feeling sufficiently strong to take the offensive. During the course of the year heavy fighting had taken place in Georgia, leaving the British with the advantage. But the war was not to be decided in the far south.

In the early months of 1780 General Cornwallis arrived before Charleston to begin the reconquest of South Carolina. This began the terrible fighting that took place through 1780 and 1781, with battles at Camden, King’s Mountain, Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse, Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton establishing his reputation in the ruthless struggle.

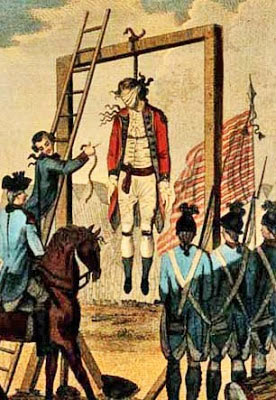

In the North, in November 1780, Benedict Arnold changed sides, escaping to the British lines, but leaving Clinton’s adjutant, Major André, in American hands to be hanged as a spy.

In February 1781 Cornwallis moved into North Carolina, shadowed by Major General Nathaniel Greene. In May 1781 Clinton moved into Virginia. The British strategy had lost all apparent direction.

By July 1781 Cornwallis was in Yorktown, which in August he began to fortify. American and French forces force marched to confront him, General Washington marching south from New York. The French fleet gathered off the York River. The British fleet under Admiral Graves had sailed further south.

On 19th October 1781 Cornwallis capitulated to General Washington and the French commander, de Rochambeau. The war was over and the American colonies had won their independence.

Steuben’s retraining of Washington’s Army at Valley Forge, Winter 1777/1778.

Throughout the Revolutionary War Congress was plagued by adventurers from Europe, arriving with written introductions from the American representatives in Paris, fantastic claims of prior rank and experience and demands for senior appointments in the American Army. A few were worthy of the demands they made.

One was Steuben. Steuben claimed to have been a baron and to have held high command in the Prussian Army. It seems more likely he served in a non-commissioned rank and rose to be a junior officer during the Seven Years War.

Steuben arrived at Valley Forge in February 1778 speaking only German and French. General Washington invited Steuben to devise a training system for the American regiments of foot. The essence of military manoeuvre was foot drill and weapon handling, both arts at which the Prussian service excelled.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

The American Army was sorely in need of instruction in battle drill. Many units could only move about in single file. A regiment of 500 men in single file takes up 1,500 yards of road or more. A similar regiment in column of fours takes up 400 yards.

In the course of the Seven Years War in Europe, the Prussian Army suffered so many casualties that the training of new recruits became an essential skill for junior officers, even when on operations. There could be no better trainer of soldiers than an experienced and competent Prussian officer.

It is part of the patriotic mythology of the American Revolution that the American colonists were fighting the best army in Europe in the British Army. This was not the case. The British Army was decades behind the Prussian Army in the education of its officers and the training of its soldiers. In the smarter British regiments, excessive military zeal was considered ungentlemanly. So far as possible in such regiments, duty matters were left to the sergeants and corporals. The new American Army inherited much of the British attitude. Steuben changed this. In the Prussian tradition, Steuben required the officers to drill the soldiers. In this way, the officers learned their military trade, while the companies and regiments welded into effective military units.

Steuben began his new appointment by forming a demonstration battalion, with men taken from all the regiments in the army. Steuben taught them battle drill and they went away and taught their regiments. Whenever Steuben held a parade, other soldiers gathered to watch.

Benedict Arnold going aboard the British sloop Vulture after deserting his post at West Point in 1780

Steuben insisted that every soldier be issued with a standard musket and bayonet. He taught them to load and fire in battle conditions and to use the bayonet as an effective offensive weapon. Steuben reduced his instructions to a set of written orders. These orders were translated into English and written out in longhand so that every regiment had a copy.

Steuben appreciated the material he had to work with. He commented that no European army would have held together in the conditions of destitution at Valley Forge. His training sessions were punctuated with outbursts of swearing in German at some mistake, followed by loud laughter on the part of everyone. Steuben appreciated that his instructions did not have to be enforced with the whip as in a European army.

Steuben had only a few months to complete his work. In June 1778, Clinton began his withdrawal from Philadelphia, and Washington marched out to intercept him, with a transformed army. The results were seen in the hard fighting at the Battle of Monmouth.

The British Army in the Revolutionary War:

The British army in North America suffered from a number of incapacitating weaknesses: it’s small size, the lack of a workable recruitment system, once the New England hinterland was closed to it, the professional incapacity of many of its officers, the lack of proper training, the lack of an organised supply system and the inadequate number of cavalry and artillery.

At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, the British Regular Army comprised 2 Troops of Horse Guards, 5 Regiments of Horse, 3 Regiments of Dragoon Guards, 14 Regiments of Dragoons, 3 Regiments of Light Dragoons, 3 Regiments of Foot Guards and 70 Regiments of Foot. The Royal Artillery was a separate institution formed into field companies in time of war.

The Regiment was the permanent unit structure, commanded by its colonel with two further field officers; a lieutenant colonel and a major. By the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, regiments were commanded in the field by the lieutenant colonel.

The English establishment for a mounted regiment was 6 or 8 troops, each comprising a captain, a lieutenant, a cornet, 3 corporals, a trumpeter and some 30 private men. A dragoon troop comprised an additional 3 sergeants and a drummer rather than a trumpeter.

The English establishment for an infantry regiment was 10 companies: the two flank companies, grenadier and light, and 8 line companies, each comprising a captain, a lieutenant, an ensign, 3 sergeants, 3 corporals, 3 drummers and 70 to 100 private soldiers. At full war strength a regiment varied from 700 to 1,000 men.

Regiments, other than the Horse and Foot Guards, moved from place to place, billeted on civilian households while in Britain and Ireland, or in barracks when in garrison in Gibraltar or Minorca. A few regiments were posted to India.

The Army used the Irish Establishment to store regiments in cadre form with greatly reduced establishments.

Each regiment conducted its own recruiting, sending out parties from its quarters. When a regiment was required to move overseas, its manpower would be made up with drafts of men from other regiments. While the regiment was overseas, recruiting parties were sent back to Britain.

Private soldiers in regiments of horse and dragoons were armed with a sword and a musket. Infantry soldiers were armed with a musket and a bayonet. The musket was muzzle loading with a flintlock mechanism at the butt end of the barrel. The soldier’s normal battle supply was 24 cartridges. Each cartridge contained a single discharge of gun powder and a spherical lead ball. When loading the soldier ripped open the paper cartridge with his teeth and poured a small quantity of powder into the firing pan. He poured the remainder of the charge into the muzzle of the musket, followed by the cartridge paper as a wad, and poked the charge to the bottom of the barrel with the ramrod carried in a cradle under the musket barrel. The soldier put the musket ball into the barrel so that it rolled, or he pushed it with the ramrod, to the bottom of the barrel, on top of the charge of gunpowder. The soldier cocked the flintlock mechanism, aimed the weapon and pulled the trigger. This caused the flintlock to strike, lighting the powder in the firing pan, which in turn ignited the charge in the barrel via a small hole in the side of the barrel. The musket discharged the ball, with a flash, a considerable quantity of smoke and a roar.

A well trained soldier could make 2 or 3 discharges in a minute.

A major feature of every battle of the period was the pall of gun powder smoke generated by the cannon and musket fire. As the battle progressed the weapons became befouled and increasingly difficult to load and fire efficiently.

In the charge, the cavalrymen relied upon their swords and the infantrymen on their bayonets.

During the Seven Years War (the French and Indian War) 1755 to 1762, the Regiments fighting the French in Germany were formed into brigades with staff and supply structures. With the end of the war the brigades were dismantled.

The colonel was paid a sum to maintain his regiment in all respects, except weapons which were issued centrally. Soldiers and officers were expected to feed themselves from their pay, forming messes to pool their resources in buying and cooking food. A similar system applied in all European Armies. When an army on campaign pitched camp, the locals would gather and sell their produce to the soldiers. A thriving market was a feature of every military camp.

This system did not work in North America. Large areas of the country were sparsely populated and it was unrealistic to rely on local supply. General Braddock on arriving at Fort Cumberland in Western Maryland in April 1755 was incensed to find there was no market (Braddock’s defeat Part 7). He assumed his men were intercepting the country folk and preventing them from coming into the camp. He found it hard to grasp that there were no country folk in the hundreds of miles of forest inhabited only by Indians and a few enterprising colonists. Every new British commander had to learn the same lesson. Burgoyne’s failure to do so, in spite of his experience in North American, led in part to his defeat and surrender at Saratoga in October 1777.

On the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, most of the British troops in the American colonies were billeted in Boston. There was no cavalry, few field guns and no field supply system.

The British Army possessed no standard training system for officers or soldiers. The regiments varied greatly in competence and reliability, depending on the professional commitment of their officers, particularly the lieutenant colonel and major.

Several infantry regiments held high reputations in the Revolutionary War; the 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, the 33rd Regiment and, on their arrival in America, the composite battalions of Foot Guards (formed from the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Foot Guards).

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

During the Revolutionary War, the British Army adopted the Seven Years War practice of forming light and grenadier companies into single battalions, the companies spending much of the time away from their parent regiments.

Americans pulling down the statue of King George III on Bowling Green in New York City in 1776: American Revolutionary War

Two cavalry regiments joined the British army in America in the early stages of the war, the 16th Queen’s Light Dragoons and the 17th Light Dragoons. The light dragoon regiments were raised during the Seven Year War and particularly distinguished themselves in the fighting against the French in Germany (see the Battle of Emsdorf for the 15th) and in Portugal and Spain. Light dragoons were “cutting edge” military units for the British Army and attracted the best and most professional cavalry officers. Both General Burgoyne and Colonel Banastre Tarleton were light dragoon officers.

The shortage of cavalry in the Revolutionary War was a major drawback for the British. A strong cavalry presence at battles like Long Island and Brandywine could have enabled the British to encircle the Americans and prevent their retreat. It is possible that a strong cavalry force would have captured Washington’s army entirely during the march south through New Jersey in 1776.

The pervasive problem for all the British regiments was recruitment. Regiments lived on the road taking everything with them. There was no depot system. Consequently the regiments posted across the Atlantic to America had no easy way to recruit replacements for casualties. There was a certain amount of recruitment in the colonies, but many loyalists prepared to fight for the British Crown preferred to join locally recruited units, rather than commit themselves to a lifetime of military service in the royal regiments.

The unpopularity of the American War in Britain was another inhibitor on recruitment into the army. Once the war widened to include France and Spain, more readily identified by the British population as enemies, recruitment into the army increased. Until that point was reached the British Government was compelled to rely heavily on mercenary regiments recruited from North German principalities, which took prominent parts at battles such as Trenton and Hubbardton.

British Regiments suffered a haemorrhage of desertion, with soldiers changing sides, sometimes for promotion or even a commission in the American Continental Army. The regiments that remained in America for the duration of the war dwindled away, although boosted at times by the arrival of drafts from regiments based in Britain.

In spite of these handicaps, several British regiments showed themselves to be formidable fighting units. The American War provided the British Army with a wealth of experience that bore fruit in the Napoleonic Wars, with the formation of the light infantry and rifle regiments that performed so well in Portugal and Spain. The 60th Rifles was, of course, the Old Royal American Regiment that provided the backbone for the British Armies in the French and Indian War.

With the entry of France and Spain into the war on the side of the American colonies, Britain was forced to withdraw regiments from America to defend the West Indies. Troops were retained in Britain in case of a French invasion. Newly raised regiments went to Gibraltar and other areas of the Mediterranean, instead of reinforcing the army in the American colonies. Increasingly, American armies outnumbered their British opposition.

For the British establishment and people, the American Revolutionary War was a humiliating disgrace. King George III, in despair at the loss of ‘his colonies‘, determined to give up the throne of Britain and retire to Hanover. He drafted several instruments of abdication but, in the end, signed none of them.

The soldiers, who fought hard for six years to maintain the British Crown in America, returned home to find themselves ignored. Victories like Long Island and Brandywine do not appear as battle honours on any regimental colours.

The End of the Revolutionary War:

The end of the war was formally negotiated in the Treaty of Paris during the summer of 1783.

While the negotiations began with the United States of America, France, Spain and the Netherlands on one side and Britain on the other, the United States’ representatives, Benjamin Franklin, John Hay, Henry Laurens and John Adams quickly realised they could obtain a better deal by negotiating directly with Britain. This is what happened.

Article 1 of the Treaty established the United States of America as a sovereign state.

The treaty was signed in Paris on 3rd September 1783 and ratified by Congress on 14th January 1784.

The War of the Revolution was finally over and the United States of America established as an independent country.

American Days commemorating the American Revolutionary War:

The primary day is Independence Day held on 4th July. Other days are or were: Evacuation Day (Suffolk County/Boston, Massachusetts on 17th March), Bunker Hill Day (Suffolk County/Boston, Massachusetts on 17th June), von Steuben Day (New York and other cities with German populations in mid-September), Evacuation Day (New York on 25th November-no longer observed), Great Jubilee Day (Connecticut on 26th May-no longer observed), Bennington Battle Day (Vermont on 16th August), Carolina Day (South Carolina on 28th June), Founder’s Day (USA on 28th November), Halifax Day (North Carolina on 12th April), Massacre Day (Boston on 5th March-no longer observed), Powder House Day (New Haven, Connecticut on 22nd April), Yorktown Day (Yorktown, Virginia on 19th October), Patriots Day (Massachusetts and Wisconsin initially on 19th April and now 3rd Monday in April), General Pulaski Memorial Day (New York City on 11th October), Casimir Pulaski Day (Illinois and other states on 1st Monday of March).

George Washington enters New York on ‘Evacuation Day’, 25th November 1783, after the departure of the British: American Revolutionary War: picture by Edmund Restein

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Battles of the War of the American Revolution 1775 to 1783:

Introduction (above):

Battle of Lexington and Concord: The opening shots of the American Revolutionary War on 19th April 1775, that ‘echoed around the world’.

Battle of Bunker Hill: The British ‘Pyrrhic Victory’ on 17th June 1775 in the opening weeks of the American Revolutionary War.

Battle of Quebec 1775: The unsuccessful American invasion of Canada and attack on Quebec on 31st December 1775.

Battle of Sullivan’s Island: The successful defence of Fort Sullivan on 28th June 1776 by Charleston’s recruit artillerymen against a powerful Royal Navy squadron.

Battle of Long Island: The disastrous defeat of the Americans on 27th August 1776 leading to the loss of New York and the retreat to the Delaware River.

Battle of Harlem Heights: The skirmish on 16th September 1776 in northern New York island that restored the confidence of the American troops.

Battle of White Plains: The battle on 28th October 1776, leading to the American withdrawal to the Delaware River and the capture of Fort Washington by the British.

Battle of Fort Washington: The battle on 16th November 1776 that saw the American army forced off Manhattan Island and compelled to retreat to the Delaware River.

Battle of Trenton: George Washington’s iconic victory on 26th December 1776 over Colonel Rahl’s Hessian troops after crossing the frozen Delaware River; the battle that re-invigorated the American Revolution.

Battle of Princeton: The sequel on 3rd January 1777 to the successful Battle of Trenton: the two battles began the resurgence of the fortunes of the American Colonists in the Revolutionary War.

Battle of Ticonderoga 1777: The humiliating American abandonment of Fort Ticonderoga on 6th July 1777 to General Burgoyne’s British army.

Battle of Hubbardton: The hard-fought battle on 7th July 1777 in the forest south-east of Fort Ticonderoga.

Battle of Bennington: The battle fought on 16th August 1777 that did much to raise the morale of the American colonists and made Brigadier Stark an American hero.

Battle of Brandywine Creek: Major-General Sir William Howe’s outflanking of General Washington’s position on 11th September 1777 in the British advance to take Philadelphia.

Battle of Freeman’s Farm: The Battle fought on 19th September 1777 General Burgoyne had to win decisively but failed to do so.

Battle of Paoli: The surprise night attack on 20th/21st September 1777 by the British on the camp of General ‘Mad Anthony’ Wayne’s Pennsylvanians: also known as the ‘Paoli Massacre’.

Battle of Germantown: General George Washington’s unsuccessful attempt on 4th October 1777 to retake Philadelphia; the battle that helped convince the French and Spanish the American cause was worth supporting with military and naval intervention against Britain.

Battle of Saratoga: The surrender of General Burgoyne’s British Army to the American Colonists on 17th October 1777, bringing France and Spain into the war.

Battle of Monmouth: The battle fought on 28th June 1778 by the American Continental Army against the British, after the 1777/8 winter spent training under Steuben.

Siege of Savannah: The unsuccessful attempt by the Americans and the French to re-take Savannah, Georgia, on 9th October 1779.

Siege of Charleston: The siege and capture of Charleston, capital of South Carolina, by the British on 12th May 1780.

Battle of Camden: The British victory on 16th August 1780 over General Horatio Gates in North Carolina.

Battle of King’s Mountain: The savage ‘All American’ battle on 7th October 1780, where the only Englishman present was the loyalist commander, Major Patrick Ferguson.

Battle of Cowpens: Daniel Morgan’s victory over the notorious Tarleton on 17th January 1781.

Battle of Guilford Courthouse: Cornwallis’s Pyrrhic victory over Nathaniel Green in the North Carolina countryside on 15th March 1781.

Battle of Yorktown: General George Washington’s resounding victory and the surrender of Lord Cornwallis’s British army on 19th October 1781; the end for Britain in the American Colonies.

Siege of Gibraltar: The siege of Gibraltar, between 1779 and 1783, whose defence under General Eliott so inspired Great Britain at a time of defeat in the American Revolutionary War.

Battle of Cape St Vincent 1780: ‘The Moonlight Battle’: Admiral Sir George Rodney’s decisive naval victory on 16th January 1780 over a Spanish Fleet, that enabled Rodney to re-supply Gibraltar.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

Podcast: Introduction to the American War of the Revolution, 1775–1783: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.