General Wolseley’s defeat of the Egyptian Army on 13th September 1882, leading to the occupation of Egypt by Britain and France

British Foot Guards at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Alphonse de Neuville

The previous battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Ulundi

The next battle of the Egypt and Sudan War of 1882 is the Battle of El Teb

To the Egypt and Sudan War 1882 index

Lieutenant General Sir Garnet Wolseley (in hat) and his staff: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

Battle: Tel-el-Kebir

War: Egypt and Sudan 1882

Date of the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir: 13th September 1882

Place of the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir: North-Eastern Egypt

Combatants at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir: An Anglo-Indian Army against the Egyptian Army.

Commanders at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir: Lieutenant General Sir Garnet Wolseley against Ahmed Arabi Bey.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir: The Egyptian army was probably around 20,000 troops with 60 guns. The British and Indian force comprised 11,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry and 45 guns.

Ahmed Arabi Bey, Egyptian commander at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir: The British infantry was armed with the single shot breech-loading Martini-Henry rifle and bayonet. The war marked a distinct change in the British Army’s approach to campaign dress. The main body of the infantry started the war in scarlet tunics and blue woollen trousers, with white equipment and tropical helmets. The importance of being less visible was soon brought home to the regiments and tunics were dyed drab and the pipe clay washed off equipment. Several regiments fought in blue tunics, the Royal Marine Light Infantry, Royal Artillery and the Royal Horse Guards. The King’s Royal Rifle Corps fought in rifle green tunics and trousers. The Highland regiments fought in kilts, other than the Highland Light Infantry and the 72nd Highlanders (1st Battalion, the Seaforth Highlanders – see below). The Indian Army regiments all wore drab or grey uniforms.

1st Life Guards in the Charge at Kassassin: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Harry Payne

The Egyptian troops wore Turkish uniforms of white tunic and trousers, spats and fezzes and were armed with single shot Remington rifles.

7th Dragoon Guards in Home Service uniform: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Orlando Norie

Winner of the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir: The British and Indian Army.

British Regiments at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir:

N/A Battery, Royal Horse Artillery

1st Life Guards

2nd Life Guards

Royal Horse Guards

4th Dragoon Guards

7th Dragoon Guards

19th Hussars

3 batteries of the Royal Artillery: N/2, A/1 and D/1.

5th and 6th Batteries of the Royal Artillery, siege artillery

Royal Engineers: pontoon and telegraph troops, 8th and 17th Companies.

2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards

2nd Battalion, Coldstream Guards

1st Battalion, Scots Guards

2nd Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment

2nd Battalion, Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry

1st Battalion, Black Watch

3rd Battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps

2nd Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

2nd Battalion, Highland Light Infantry

1st Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers

1st Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders

1st Battalion, Gordon Highlanders

1st Battalion, Cameron Highlanders

Indian Regiments at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir:

2nd Bengal Cavalry (Gardner’s Horse)

6th (King Edward’s Own) Bengal Cavalry

13th Bengal Cavalry (Watson’s Horse)

2nd Queen’s Own Sappers and Miners

7th Bengal Infantry (Rajputs)

20th (Brownlow’s) Punjab Infantry

29th Bombay Infantry (Baluchis)

Account of the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir: Egypt in the late 19th Century, ruled by the Khedive, remained a nominal part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Britain and France maintained a substantial interest in the country due to the Suez Canal, in which both countries invested heavily and which provided the most direct route to their Asian colonies; India and Australia for Britain and Indochina for France. In the 1870s, Egypt, through mismanagement and corruption, lurched towards financial collapse and political instability. Britain and France installed a commission to supervise Egypt’s government. In 1881, Colonel Ahmed Arabi Bey, a native Egyptian officer of the Egyptian Army, with other Egyptian officers launched a revolt against the Khedive and the British and French. A British naval squadron under Admiral Seymour bombarded the defences of Alexandria, Egypt’s main port on the northern coast, on 11th July 1882. A British military force assembled under Lieutenant General Sir Garnet Wolseley to invade Egypt, with the purpose of capturing Cairo and restoring the Khedive as nominal ruler with Anglo-French control of the country.

1st Scots Guards landing at Alexandria before the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

The leading elements of the British force landed at Alexandria in the second week of August 1882. The aims of the force were to secure the Suez Canal that ran north-south in the East of Egypt and then to march on Cairo, the capital of the country, which the rebels were threatening to destroy in the event of an invasion.

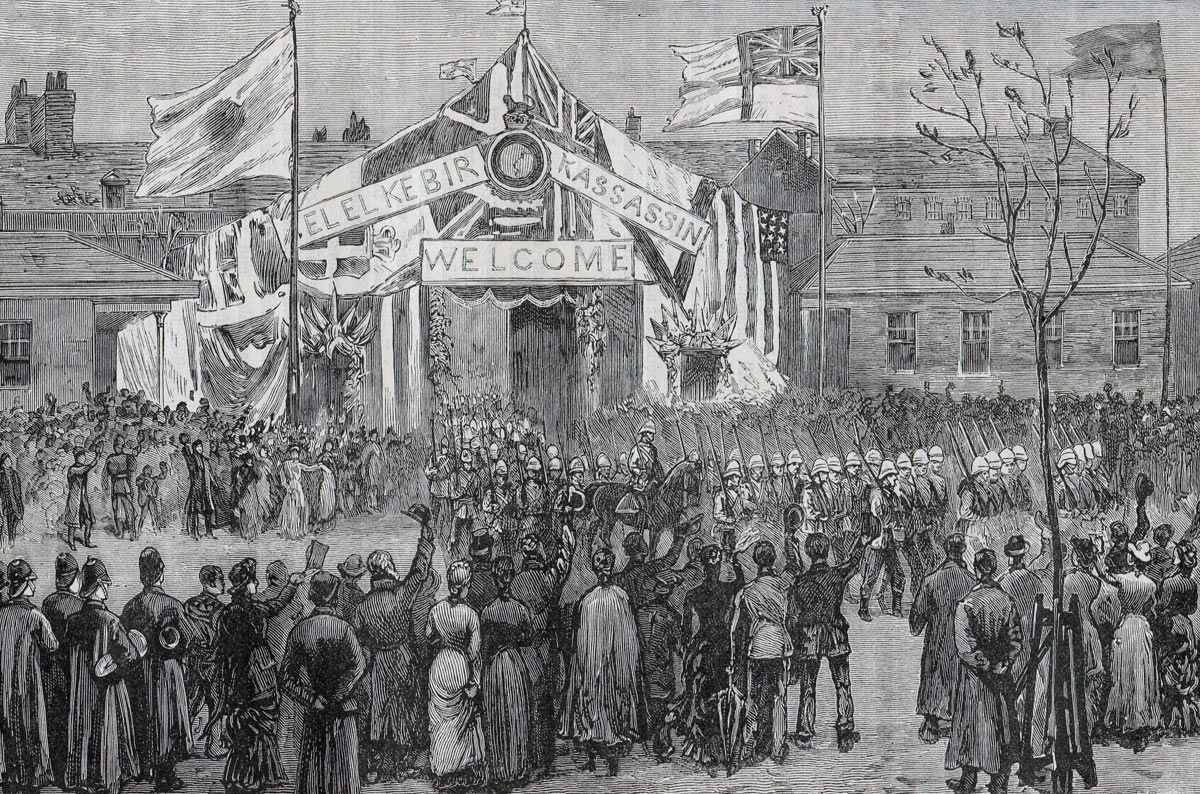

2nd Coldstream Guards leaving London for Egypt: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

An Anglo-Indian force (comprising both British and Indian regiments) was sent from India to join the British contingent on the Suez Canal.

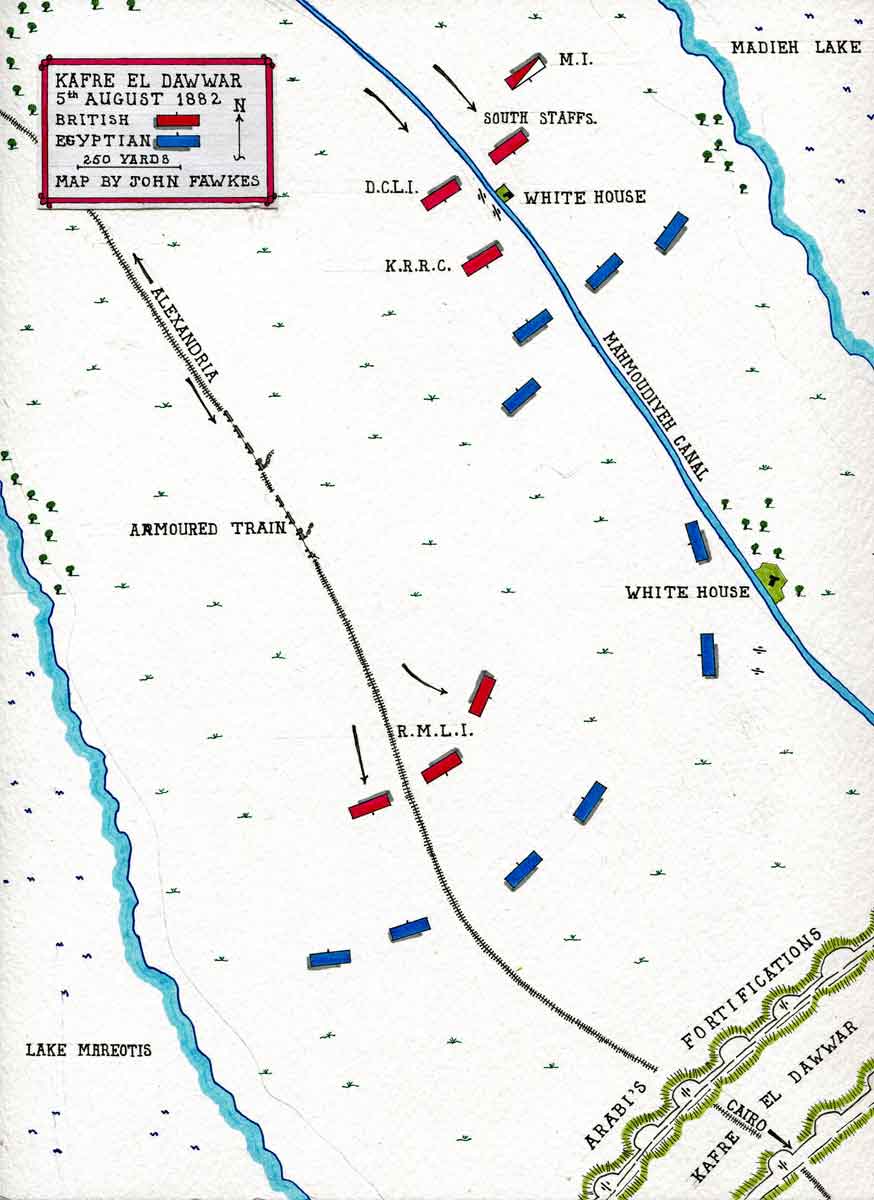

On 5th August 1882 Major General Alison conducted a reconnaissance up the Alexandria to Cairo railway line to probe the fortified line built by General Arabi at Kafre El Dawwar.

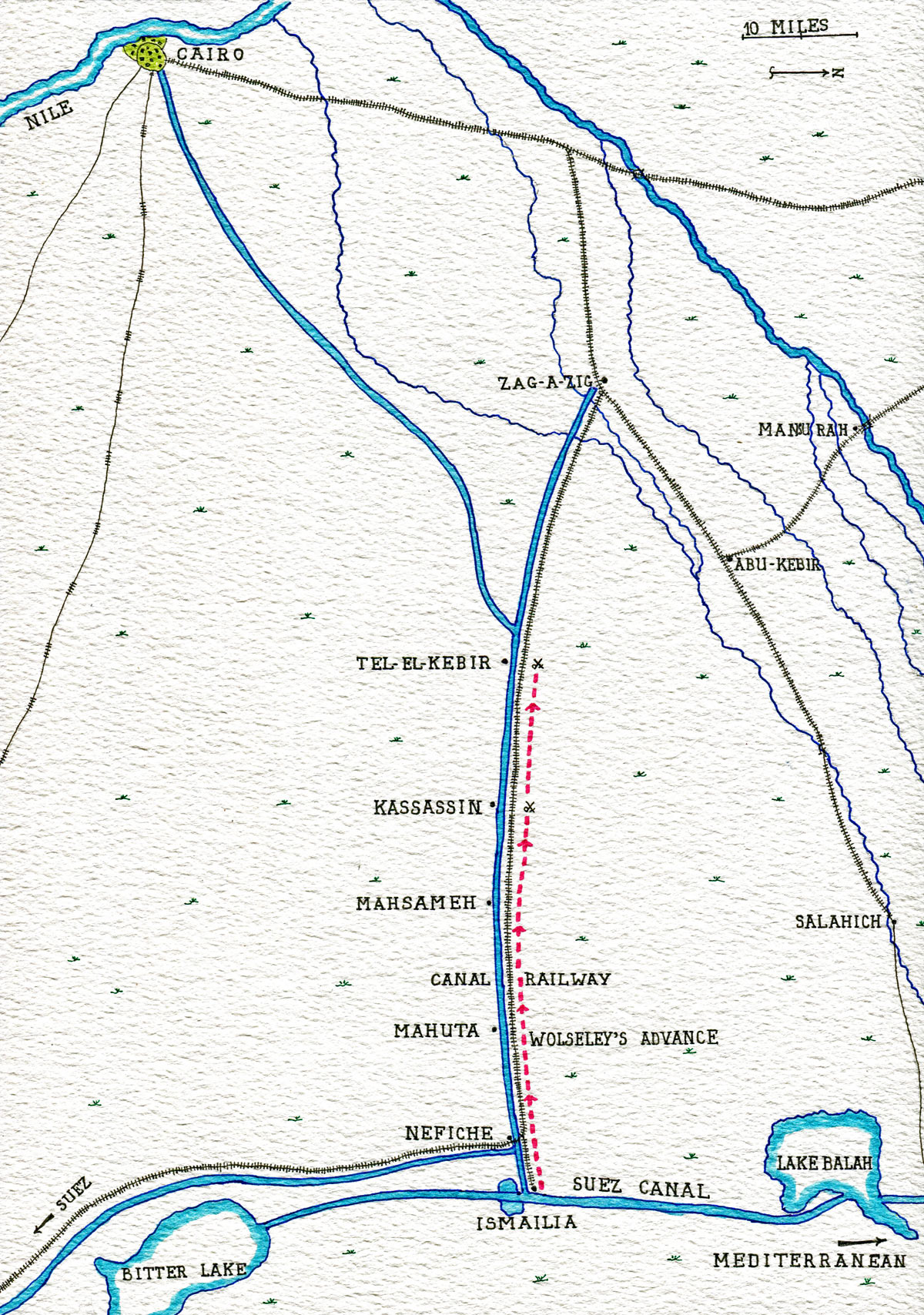

The landing at Alexandria was a feint. General Wolseley concealed his true plan from everyone except his immediate staff, which was to land at Ismailia, midway down the Suez Canal and to march west to Cairo, attacking Arabi’s army in its positions at Tel-El-Kebir on the railway and main irrigation canal.

The British contingent landed at Ismailia around 20th August 1882, securing the local barracks and canal facilities, while the Anglo-Indian contingent came up the canal from the Persian Gulf in the South.

At 4am on 24th August 1882, General Wolseley’s army marched out of Ismailia, along the line of the railway, moving west towards Cairo, to attack Arabi’s army at the town of Tel-El-Kebir.

Arabi’s army had in the meanwhile dammed the irrigation canal that ran alongside the railway, with the aim of cutting off the water supply to Wolseley’s army and the town of Ismailia.

General Graham’s brigade was pushed forward to Kassassin, where there was a lock on the irrigation canal. Graham’s brigade adopted a position across the railway line and the canal.

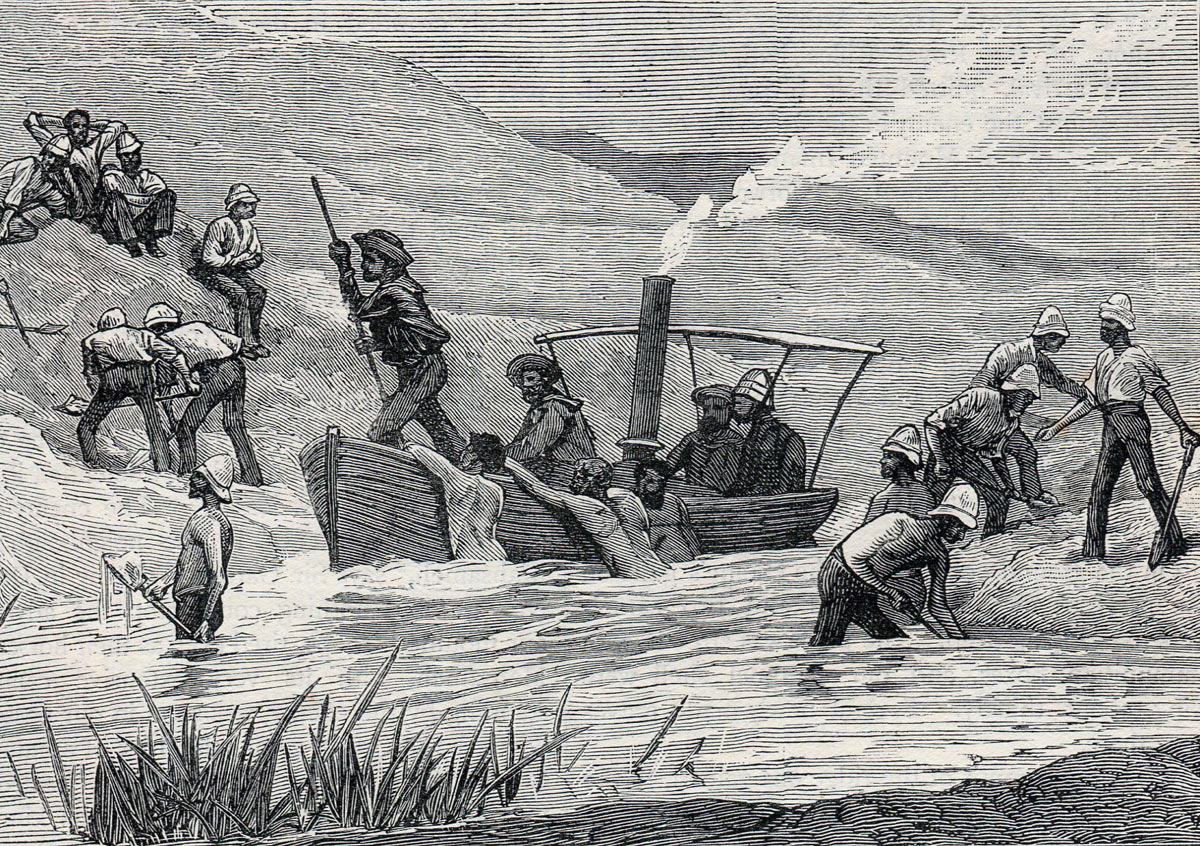

Royal Navy steam pinnace and soldiers clearing the dammed stream: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

Late on 24th August 1882, an Egyptian force, comprising guns and infantry, appeared to the north of Graham’s position. Graham engaged them. Seeing that the Egyptians’ flank was exposed, Graham directed Major General Drury-Lowe to attack the Egyptians with the cavalry brigade.

Map of the Tel-el-Kebir campaign, showing Wolseley’s advance from Ismailia to Tel-el-Kebir: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: map by John Fawkes

Drury-Lowe lead forward his mounted force, comprising a composite regiment of Household Cavalry (a squadron from each of the 1st Life Guards, 2nd Life Guards and the Royal Horse Guards, the ‘Blues’) and 7th Dragoon Guards with four guns of N/A Battery, Royal Horse Artillery.

Highland Brigade assaulting the Egyptian entrenchments at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

Drury-Lowe was aided in reaching the battle line by the gun flashes in the gathering darkness. The first fire was opened by the Egyptians. Drury-Lowe engaged them with his guns and then launched the Household Cavalry in a charge. The Egyptian infantry were swept away and their guns abandoned and captured in the ‘Moonlight Charge’ of the Battle of Kassassin.

Charge of the Household Cavalry at Kassassin: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by J. Richards

Informed of this success, Graham returned to his positions at Kassassin. General Sir Garnet Wolseley completed the build-up of his army around the Kassassin position by 12th September 1882. Arabi’s Egyptian army lay at Tel-El-Kebir some ten miles distant. Tel-El-Kebir comprised a small town to the south of the line of the canal and the Cairo-Ismailia railway, that ran parallel and to the north of the canal.

Over the preceding weeks, the Egyptian army of some 20,000 soldiers with 59 guns, some of them modern German Krupp-made weapons, had built a length of entrenchment, starting with redoubts at the canal and railway and stretching north some three miles to the end of a raised section of ground. A second section of entrenchment covered the Egyptian camp to the rear.

Highlanders advancing at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

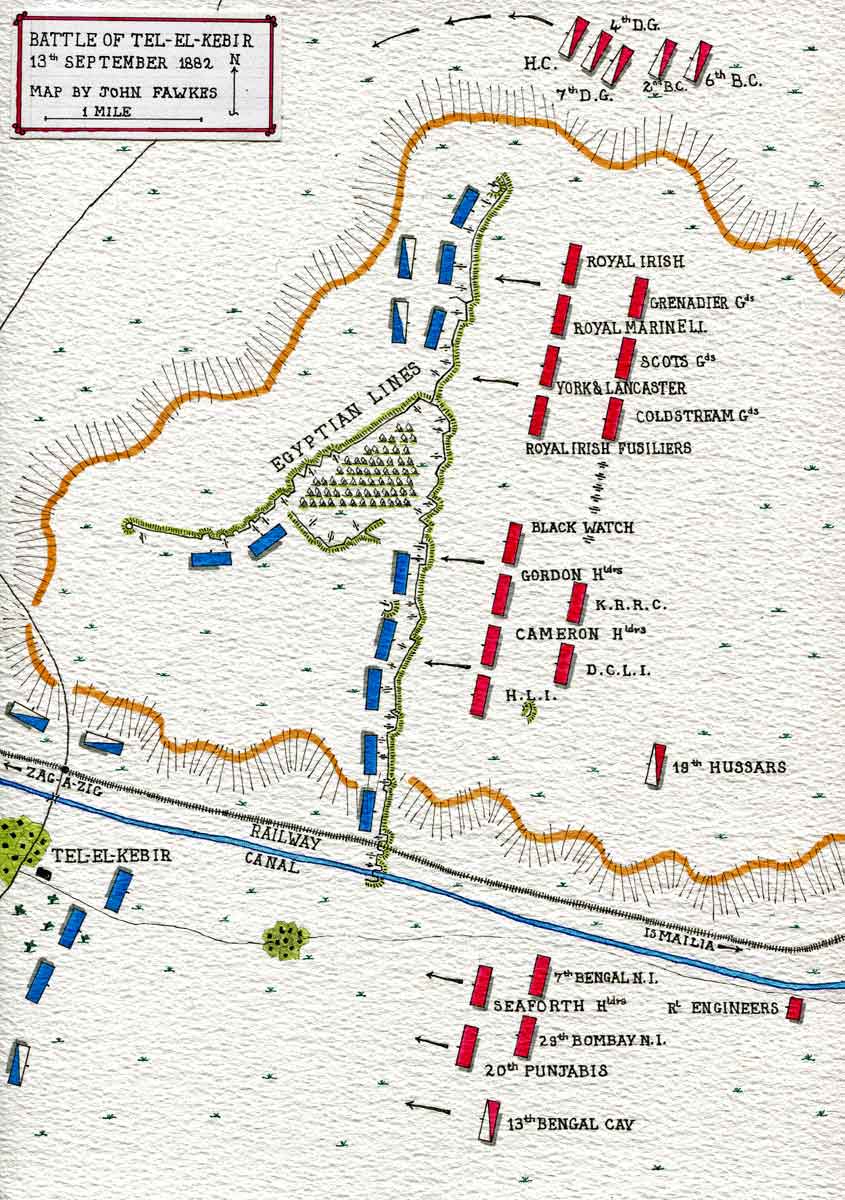

General Wolseley resolved to attack the Egyptian line at dawn on 13th September 1882, following a night approach march. His army formed up with the Second Division, commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Edward Hamley, on the left; the Highland Brigade leading with the second brigade of the Division in reserve immediately to its rear. The First Division took the right, with Major General Graham’s brigade to the front and the Guards Brigade, commanded by the Duke of Connaught, in reserve. The guns, commanded by Colonel Goodenough, advanced in the area between the two reserve brigades. The cavalry brigade commanded by Major General Drury-Lowe, augmented to a division by the addition of the Indian mounted regiments, took the right of the army, conforming to the Guards Brigade, its role being to sweep around the Egyptian flank, once the infantry had stormed the entrenchments and make for Cairo, to prevent the destruction of the Egyptian capital by Arabi’s rebels.

Drury-Lowe’s cavalry at Kassassin: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Christopher Clark

The Indian brigade was to advance along the canal/railway line on the south side, to clear the Egyptian redoubts in that area and take the town of Tel-El-Kebir, before moving on to the next station up the line, Zag-a-Zig.

The direction of the night-time advance was to be supervised by Lieutenant Rawson, Royal Navy, navigating by the stars from the left flank.

The night march to the entrenchments went surprisingly smoothly, except that the advancing army drifted to its right. Dawn broke with the Highland Brigade (Black Watch, HLI, Camerons and Gordons), leading the British left, within 150 yards of the Egyptian line. A heavy fire immediately broke out. The four regiments of the Highland Brigade, led by its commander, Major General Allison and General Hamley, the Divisional Commander, stormed into the entrenchments, the two centre regiments, the Gordons and Camerons leading.

Black Watch at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Alphonse de Neuville

The Black Watch on the right of the brigade found the resistance hard to overcome, until supported by 3rd Battalion the King’s Royal Rifle Corps from the divisional reserve. On the left the Highland Light Infantry were unable to break into the entrenchments, until re-inforced by the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry from the reserve brigade.

On the right, General Graham’s brigade met heavy resistance but drove the Egyptians from their trenches with the support of guns from the centre.

‘Bringing up the guns’ at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by John Charlton

Following the success of the infantry attack, General Drury-Lowe took his cavalry division in a sweep around the Egyptian left flank and rode down the Egyptian rear towards the bridge crossing the canal into Tel-El-Kebir, accelerating the rout of the retreating Egyptian troops.

Black Watch storming the Eqyptian lines at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Henri Dupray

To the south of the canal, the Seaforth Highlanders (part of the Indian brigade) attacked the Egyptian redoubt, while the 20th Punjabis (Brownlow’s) moved around the Egyptian right flank and stormed a village from which fire was being directed, both battalions supported by 7th Bengal Native Infantry and 29th Bombay Native Infantry.

Highland Light Infantry assaulting the Egyptian entrenchments at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Harry Payne

The Indian brigade then moved into the town of Tel-El-Kebir. The action was finished with the Egyptian army in rout.

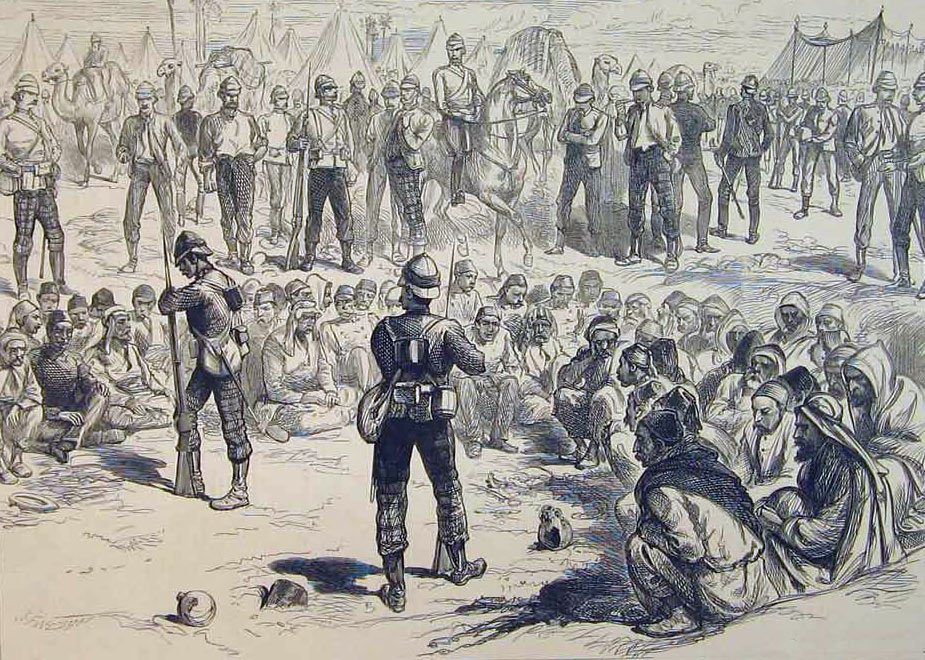

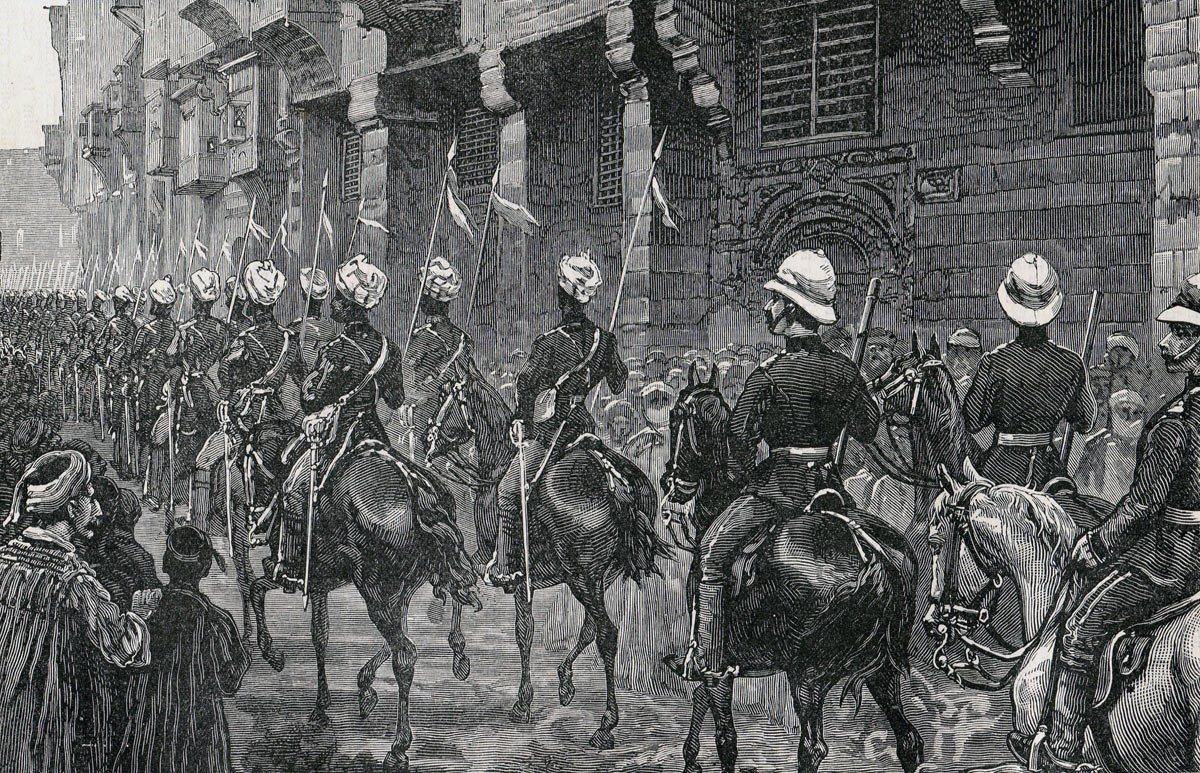

Following the battle, the cavalry division secured Cairo on 14th September 1882 and accepted the surrender of Arabi. On 25th September 1882, the Khedive re-entered his capital escorted by British and Indian troops.

4th Dragoon Guards at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Thomas Seccombe

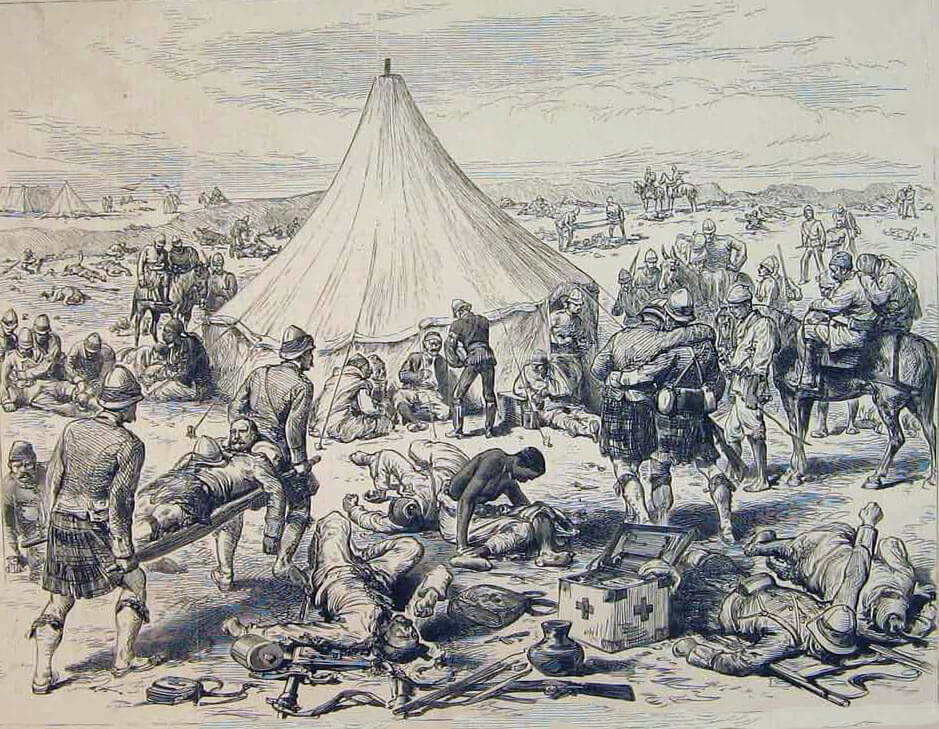

Casualties at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir:

The Egyptians are said to have suffered 2,000 dead and an unquantified number of wounded. 66 guns were captured.

The British and Indian casualties were: 9 officers and 48 non-commissioned ranks killed and 27 officers and 353 non-commissioned ranks wounded. 22 men were reported missing.

Follow-up to the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir:

The Egyptian War began Britain’s involvement in Egypt and the Sudan, leading to the campaign in the Sudan to attempt the rescue of General Gordon in 1885. British troops finally left Egypt and the Sudan after the Second World War.

Lieutenant General Sir Garnet Wolseley after the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Lady Butler

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir:

Egypt and Sudan Campaign Medal 1882 with clasp for the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War and the Khedive’s Star

- Campaign medals for the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir:

The troops involved in the Egyptian campaign received the British medal for Egypt, 1882, with the clasp, where appropriate, ‘Tel-El-Kebir’. They also received the Khedive’s bronze star from the Khedive of Egypt. - While planning the campaign in London, General Wolseley said he would win the war in a battle fought in the area of Tel-El-Kebir around the middle of September 1882, which is exactly what happened.

- Lieutenant General Sir Edward Hamley, commanding the Second Division, was a veteran of the Crimean War, having had horses shot under him at the Battle of the Alma and the Battle of Inkerman. A Royal Artillery officer, General Hamley wrote a popular history of the Crimean War.

- The reconnaissance to Kafre El Dawwar from Alexandria on 5th August 1882 used the ‘armoured train’, equipped with a naval gun, designed and constructed by Captain Jackie Fisher RN of HMS Inflexible, later First Sea Lord in the opening years of the First World War.

- Several foreign correspondents accompanied the British army. The correspondent of the Kolnische Zeitung wrote of the army: ‘… The private soldiers vary much more than ours. There are among them old and young, weak and strong. In general, the strong predominate. Many of them are splendid men, with muscles like those of the ‘dying gladiator’. The uniform is the red tunic and Indian mud-coloured helmet. The Household Cavalry, Rifles, Marines and Artillery do not wear red tunics. All, however, wear the sun helmet, which is of a beautiful shape, but an ugly colour.

Indian Cavalry entering Cairo after the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

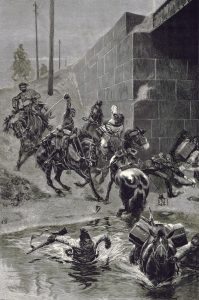

Surprising the sabotage of a bridge by Egyptian troops: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

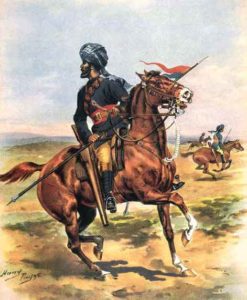

They also wear a flannel shirt and needlessly warm woollen trousers. The little wooden water-bottle that each soldier carries at his belt appears very practical, as the water keeps cooler than in flasks of tin…..The Hussars and Dragoons are to be distinguished only by their leggings, as they also wear red tunics and helmets. The Indian Cavalry look well in their uniform which resembles that of the Cossacks. They carry lances; their pointed shoes are in the style of the fifteenth century. All these men have gipsy faces with beautiful fiery eyes. They move with a cat-like softness, peculiar to all southern Asiatics. These Indians know better than anyone else how to forage and steal. Among the British officers, especially the Guards, are crowds of lords with £10,000 a year and more, but without knowing it beforehand, no one would find out…. They have almost unlimited liberty as regards uniform when not on duty. If it is difficult for the Continental European to distinguish between German regiments, it is more so when British officers not on duty wear the half military, half civilian costume. They appear in yellow leather lace-boots and gaiters, fancy coats, broad belts, gigantic revolver-pockets, scarfs, etc….As far as I was able to judge, they did not trouble themselves much about their men….’

- The Egyptian campaign formed a clear marker in the change of campaign dress to the more utilitarian. The Royal Marine Light Infantry and some of the other regiments abandoned pipe clay and stained their white equipment and helmets with tea and tobacco juice. Several of the Indian regiments already wore grey or drab which was adopted by British regiments. New drab jackets arrived for the army, but too late for the fighting.

- The 72nd Highlanders arrived from India, where they had taken a prominent and successful part in the Second Afghan War. While the 1882 reforms saw the 72nd become the 1st Battalion, the Seaforth Highlanders, a kilted regiment wearing the Mackenzie tartan, the 72nd were still clothed in their Stuart tartan trews, having had no opportunity to re-clothe.

- During the attack on the Egyptian entrenchments one of the guns of N/2 Battery of the Royal Artillery broke a wheel. The battery and its successor took the nickname ‘The Broken Wheel Battery’.

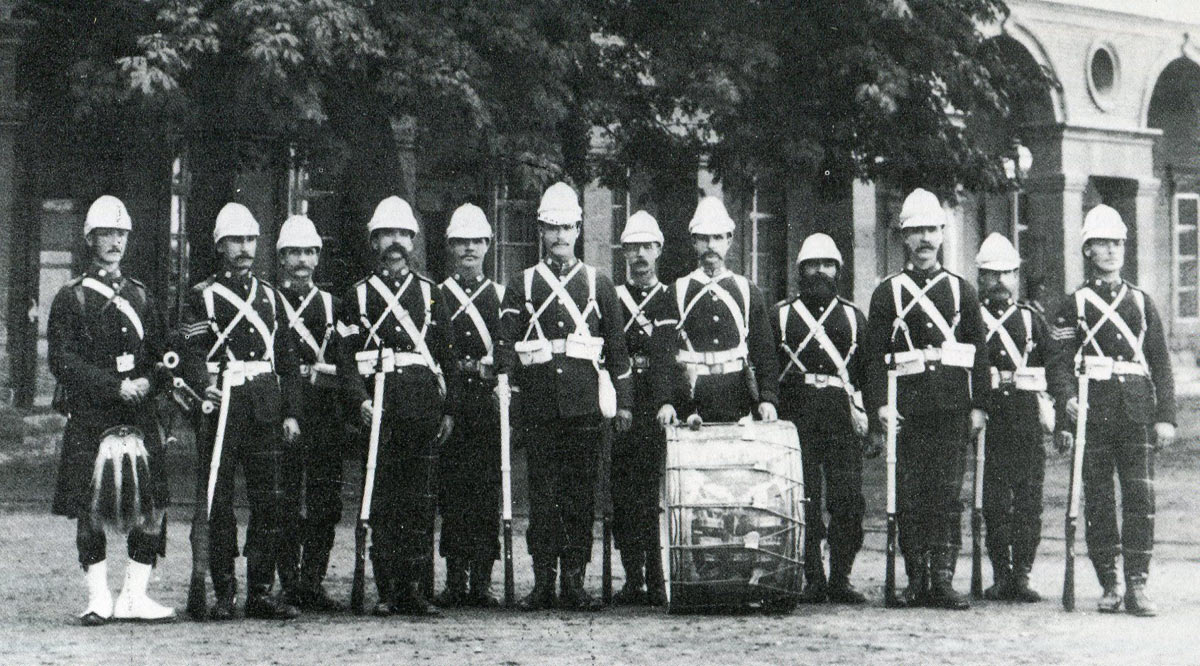

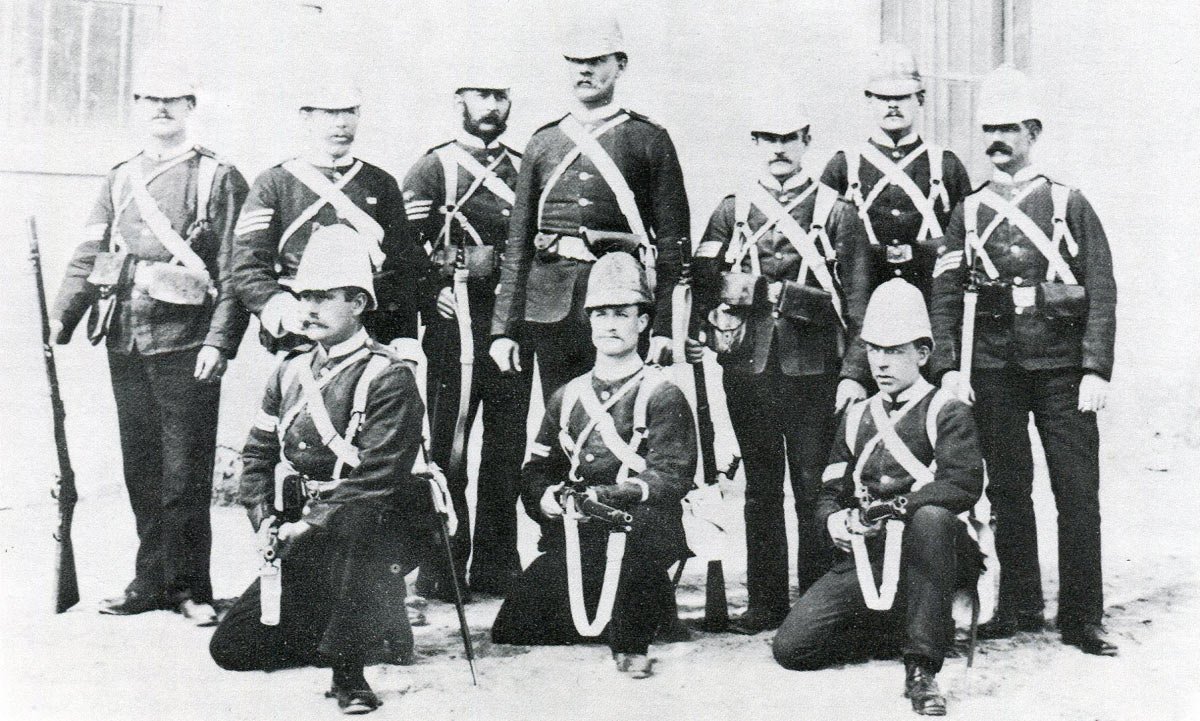

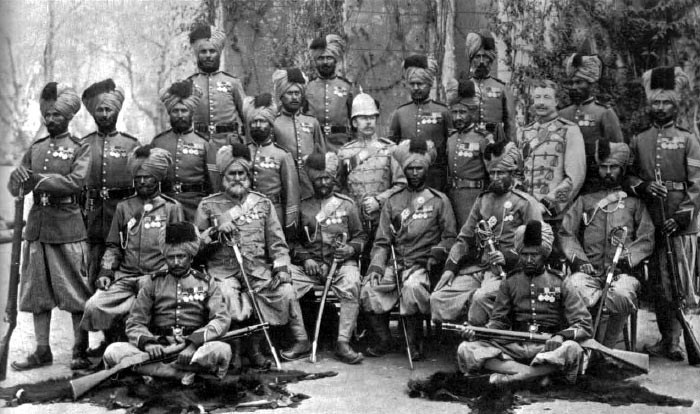

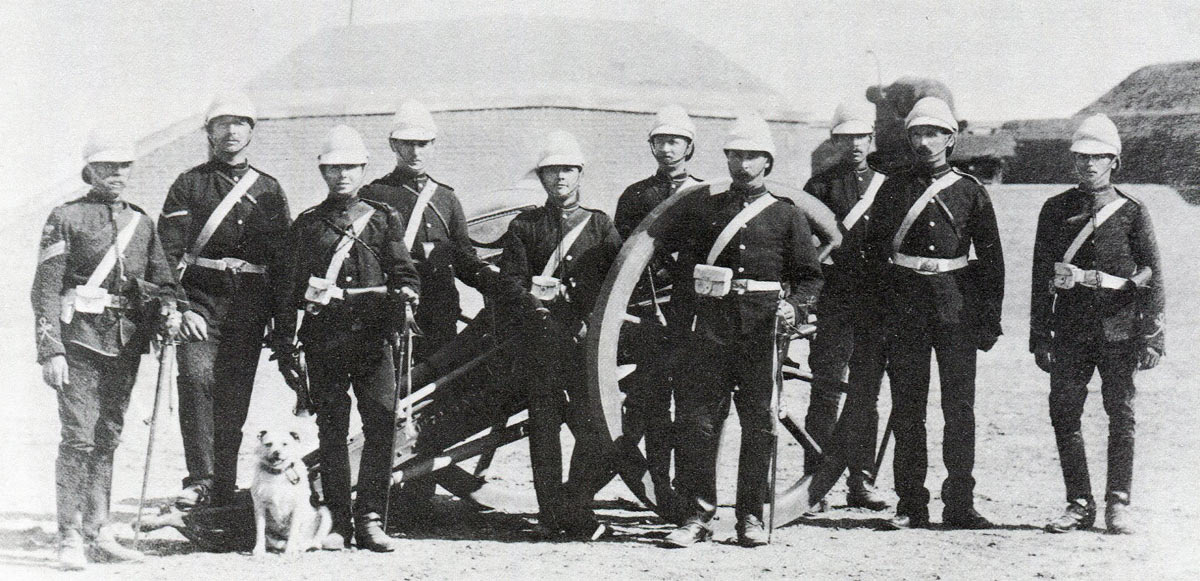

- Queen Victoria directed that she be provided with photographs of selected soldiers from each of the regiments that fought at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir. Some of these photographs are set out below:

2nd Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

Gatling Gun team from HMS Monarch at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

Soldiers from 20th Bengal (Punjabi) Infantry: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

N/2 ‘Broken Wheel’ Battery Royal Artillery: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War

References for the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir:

War on the Nile by Michael Barthorp

British Battles by Grant

History of British Cavalry Volume 3: 1872-1898 by the Marquess of Anglesey

British ‘Moonlight’ Cavalry Charge at Kassassin: Battle of Tel-el-Kebir on 13th September 1882 in the Egyptian War: picture by Henry Ganz

The previous battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Ulundi

The next battle of the Egypt and Sudan War of 1882 is the Battle of El Teb

To the Egypt and Sudan War 1882 index