The spectacular but unsuccessful attempt by King Philip II of Spain to invade Elizabethan England in 1588. The Armada is for the English the classic foreign threat to their country and a powerful icon of national identity

The English Fleet gives battle to the Spanish Armada: A Spanish galeas occupies the foreground, an English “race” galleon to her left and right. English ships carry the red cross of St George on a white background: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Pinkie

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Edgehill

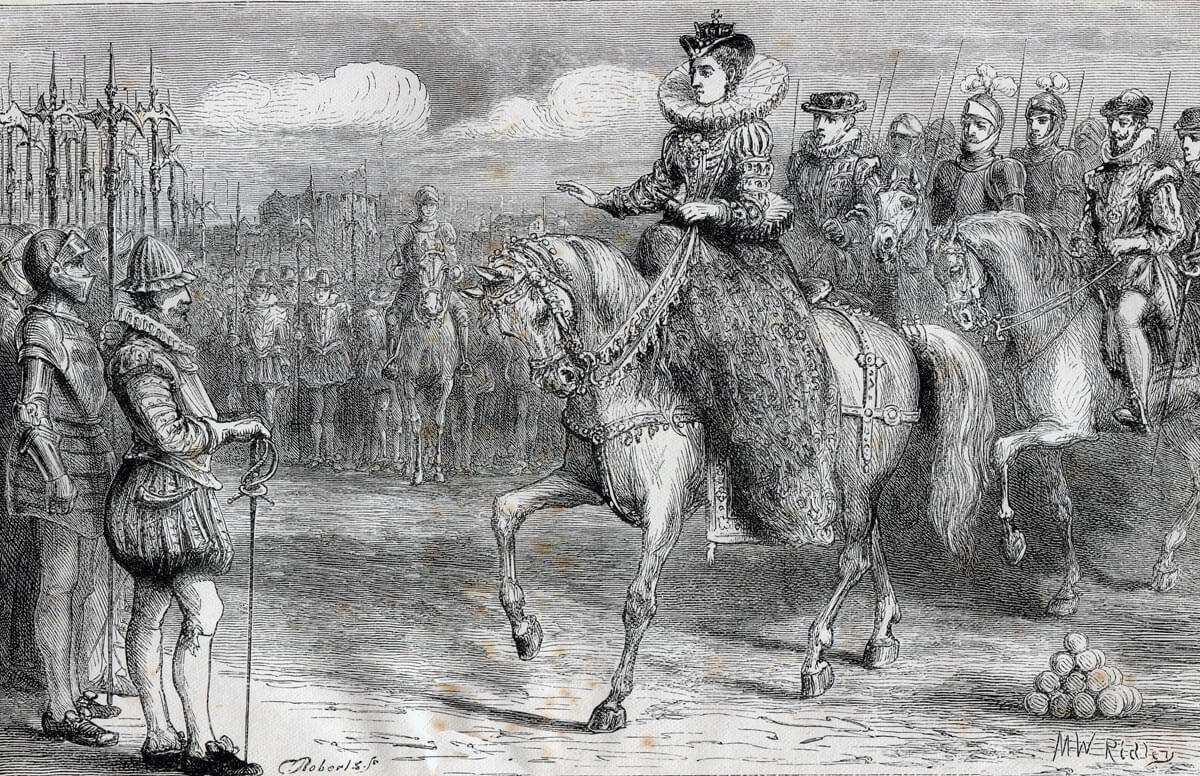

Allegorical representation of the Spanish Armada, June to September 1588, showing Queen Elizabeth I and her army watching the action off Portland Bill (the Queen was in London)

The Spanish Armada

Date: June to September 1588.

Area of the Spanish Armada campaign: The English Channel, the North Sea and the seas around the North and West of Scotland, the Orkneys and the West of Ireland.

Combatants in the Spanish Armada campaign: The Armada (Spanish for “Fleet”), manned by Spaniards, Portuguese, Italians, Germans, Dutch, Flemings, Irish and English against the English Fleet assisted by the Dutch Fleet.

Commanders in the Spanish Armada campaign: Spanish commanders were the Duke of Medina Sidonia and the Duke of Parma against the English commanders Lord Howard of Effingham, High Admiral of England, Sir John Hawkins, Sir Martin Frobisher, Sir Francis Drake, Lord Henry Seymour and Sir William Winter.

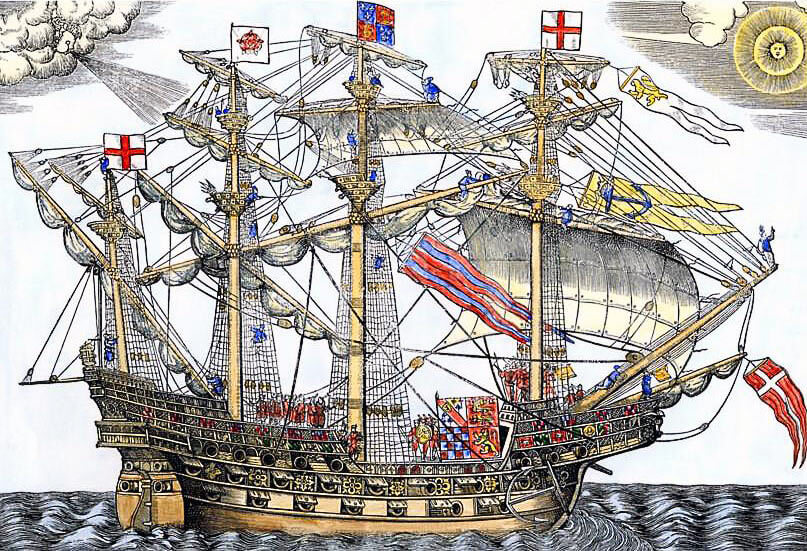

Armada, June to September 1588: Lord Howard in the Ark Royal attacks San Martin, flagship of the Duke of Medina Sidonia. Both ships carry the red cross on the white background, the crusader symbol and the symbol of St George

Size of the navies in the Spanish Armada campaign: The Spanish Armada sailed with around 160 ships. The English mobilised up to 200 ships in the Channel. Unknown numbers of Dutch vessels harassed and attacked the Armada and hemmed the Duke of Parma’s forces into their harbour of Dunkirk.

Ships, organization, tactics and equipment: The descent of the Spanish Armada on England in 1588 ocurred at a time of profound change in sea warfare. The Spanish represented the old tradition while the English fought with a new design of warship and new tactics.

In medieval warfare at sea soldiers added castles to the merchant trading vessel at the front and the rear (fore castle and after castle) and at the top of the mast and fought their fleets as if on land, discharging arrows and handguns, boarding the enemy ships and conducting hand to hand fighting.

The ships incorporated by the Spanish in the Armada represented this tradition. The main Spanish vessels were galleons, sailing ships that rode high out of the water with towering fore and after castles from which handheld firearms were discharged; while the crews grappled the enemy ships so that soldiers could board and capture them. Their height and broad beam made these ships awkward to sail.

English captains, particularly John Hawkins and Francis Drake, inspired a new form of ship for the Queen’s Navy, the “race ship”, of which around 25 were built. Lower in the water, with a long prow and much reduced fore and after castles, these sleek ships carried more sophisticated forms of rigging, enabling them to sail closer to the wind, making them faster and more manoeuvrable than the Spanish ships.

England had no standing army, so her naval vessels were crewed by sailors alone. English fighting ships relied increasingly on gunnery rather than boarding to defeat an enemy.

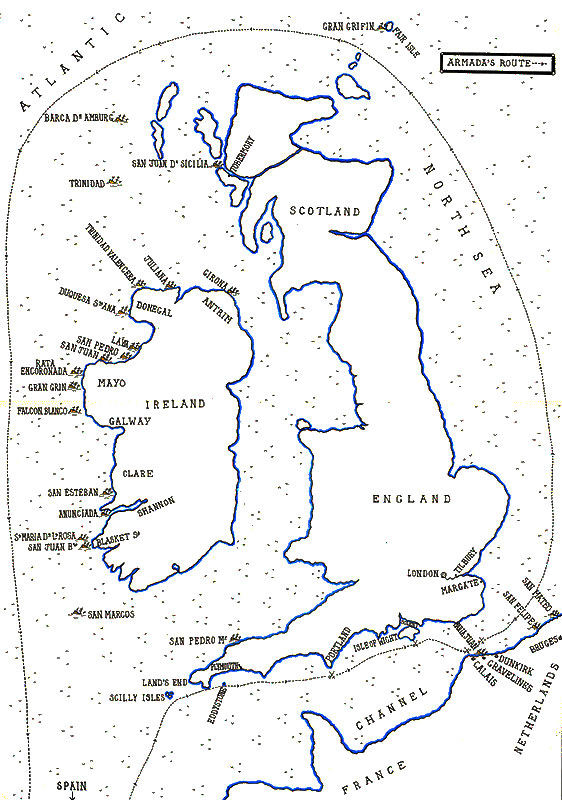

Route of the Spanish Armada in 1588, up the Channel into the North Sea, North About into the Atlantic and down the west coast of Ireland. The map shows the known wrecks of Armada ships. Of the 120 ships in the Armada half were lost many just disappearing. The map shows the sites of the engagements between the Armada and the English Fleet at Eddystone, Portland, Isle of Wight, Calais and Gravelines. Of the Armada’s complement of 30,000 soldiers and sailors 20,000 were lost: map by John Fawkes

Initially the English attempted to disable the Armada ships with long range gunfire. This form of gunnery did little damage other than to rigging which was easily replaced. The lesson was learnt and at the Battle off Gravelines the English closed in and fired repeated broadsides into the Spanish ships at short range, inflicting considerable damage and sinking several ships.

The different Spanish tradition of sea fighting prevented the Armada from countering English gunfire. Guns in Spanish ships were fired in a single salvo as a prelude to boarding; one soldier remaining by each gun for this duty while the rest of the gun teams took their places among the boarders on deck. The Spanish crews were not trained to load and fire repeatedly during a battle and the carriages and tackles of the guns were not designed or suitable for this function; the system of wheels and tackle restricting recoil rather than easing it.

Battle of Gravelines on 28th July 1588: Vanguard engages two Spanish galleons: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Throughout the Armada’s journey up the Channel and at the Battles of Portland and Gravelines the Spanish struggled unavailingly to bring the nimble English ships within grappling and boarding distance; while suffering constant bombardment that killed many men, sank some ships and damaged others to such an extent that they foundered on the voyage home.

After Gravelines it was found that no English ships had suffered hull damage, while many of the Spanish ships were severely damaged by canon fire, much of it below the waterline. Examination of Spanish canon balls recovered from wrecks showed the Armada’s ammunition to be badly cast, the iron lacking the correct composition and too brittle, causing the balls to disintegrate on impact, rather than penetrating the hull. Several guns were found to have been badly cast and of inadequate composition, increasing the danger of bursting and killing or injuring the gun crews.

Detailed records kept in the Spanish archives listed the equipment carried in each ship. From these records it was seen that the Armada carried guns of significantly greater weight than the English fleet. Study of the wrecks found off the Scottish and Irish coasts showed the largest guns not to be part of the ships’ armament but a siege train to be used on land after the invasion. The two fleets were much on a par in terms of size and numbers of operational guns.

The wrecked Spanish ships were discovered to contain a significant amount of the ammunition they had brought from Spain, while the English ships are known to have run out of ammunition by the end of the Battle of Portland and required replenishment before the Battle of Gravelines. However, much of the ammunition recovered from the wrecks proved to be of the wrong calibre for the guns carried in the ships.

A further important advance in the English service was the predominance of the sea captain over all on board his ship with a single clear chain of command; a principal decisively established by Drake when he hanged a recalcitrant gentleman called Doughty aboard the Golden Hinde. In the Spanish service the sea captain remained a lowly person, forced to defer to military officers and many others. It was never quite clear who gave the decisive orders on a Spanish ship. An interesting example of this dilemma was revealed when the Santa Maria de la Rosa in attempting to anchor in Blasket Sound off the South West coast of Ireland in September 1588, struck the terrible Stromboli rock. The pilot, who should have been entitled to take any decision on the ship’s safety, cut the anchor cable and attempted to hoist a sail to beach the catastrophically damaged vessel. Misinterpreting his actions a Spanish land officer killed him.

Winner: The Elements and the English navy.

The Navies in the Spanish Armada campaign:

The Spanish Navy comprised:

The Portuguese Galleons:

São Martinho (48 guns: Flagship of the commander-in-chief, the Duke of Medina Sidonia and Maestre de Francisco de Bobadilla, the senior army officer)

São João (50 guns).

São Marcos (33 guns).

São Felipe (40 guns).

San Luis (38 guns).

San Mateo (34 guns).

Santiago (24 guns).

Galeon de Florencia (52 guns).

San Cristobel (20 guns).

San Bernardo (21 guns).

Augusta (13 guns).

Julia (14 guns).

Merchant vessel commandeered for the Armada: print by Peter Brueghel: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Biscayan Ships:

Santa Ana (30 guns: Flagship of Juan Martinez de Recalde, Captain General and second in command of the Armada).

El Gran Grin (28 guns).

Santiago (25 guns).

La Concepcion de Zubelzu (16 guns).

La Concepcion de Juan del Cano (18 guns).

La Magdalena (18 guns).

San Juan (21 guns).

La Maria Juan (24 guns).

La Manuela (24 guns).

Santa Maria de Montemayor (18 guns).

Maria de Aguirre (6 guns).

Isabela (10 guns).

Patache de Miguel de Suso (6 guns).

San Estaban (6 guns).

Castilian Ships:

San Cristobal (36 guns: Flagship of Diego Flores de Valdés).

San Juan Bautista (24 guns).

San Pedro (24 guns).

Baltic Hulk or Urca like El Gran Grifin that

sank on Fair Isle: print by Peter Brueghel: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

San Juan (24 guns).

Santiago el Mayor (24 guns).

San Felipe y Santiago (24 guns).

La Ascuncion (24 guns).

Nuestra Senora de Begona (24 guns).

La Trinidad (24 guns).

Santa Catalina (24 guns).

San Juan Bautista (24 guns).

Nuestra Senora del Rosario (24 guns).

San Antonio de Padua (12 guns).

Andalusian Ships:

Nuestra Senora del Rosario (46 guns Flagship of Don Pedro de Valdés).

San Francisco (21 guns).

San Juan Bautista (31 guns).

San Juan de Gargarin (16 guns).

La Concepcion (20 guns).

Duquesa Santa Ana (23 guns).

Santa Catalina (23 guns).

La Trinidad (13 guns).

Santa Maria de Juncal (20 guns).

San Barolome (27 guns).

Espiritu Santo.

Guipúzcoan Ships:

Santa Ana (47 guns: Flagship of Miguel de Oquendo).

Santa Maria de la Rosa (47 guns).

San Salvador (25 guns).

San Esteban (26 guns).

Santa Marta (20 guns).

Santa Barbara (12 guns).

San Buenaventura (21 guns).

La Maria San Juan (12 guns).

Santa Cruz (18 guns).

Doncella (16 guns).

Asuncion (9 guns).

San Bernabe (9 guns).

Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe (1 gun).

La Madalena (1 gun).

Merchant vessel commandeered for the Armada: print by Peter Brueghel: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Levantine Ships:

La Regazona (30 guns: Flagship of Martin de Bertandona)

La Lavia (25 guns).

La Rata Santa Maria Encoronada (35 guns).

San Juan de Sicila (26 guns).

La Trinidad Valencera (42 guns).

La Anunciada (24 guns).

San Nicolas Prodaneli (26 guns).

La Juliana (32 guns).

Santa Maria de Vison (18 guns).

La Trinidad de Scala (22 guns).

Hulks:

El Gran Grifon (38 guns: Flagship of Juan Gómez de Medina)

San Salvador (24 guns).

Perro Marino (7 guns).

Falcon Blanco Mayor (16 guns).

Castillo Negro (27 guns).

Barca de Amburg (23 guns).

Casa de Paz Grande (26 guns).

San Pedro Mayor (29 guns).

El Sanson (18 guns).

San Pedro Menor (18 guns).

Barca de Danzig (26 guns).

Mediterranean merchant ship commandeered for the Armada: print by Peter Brueghel: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Falcon Blanco Mediano (16 guns).

San Andres (14 guns).

Casa de Paz Chica (15 guns).

Ciervo Volante (18 guns).

Paloma Blanca (12 guns).

La Ventura (4 guns).

Santa Bárbara (10 guns).

Santiago (19 guns).

David (7 guns).

El Gato (9 guns).

San Gabriel (4 guns).

Esayas (4 guns).

Neapolitan galeases:

San Lorenzo (50 guns: Flagship of Don Hugo de Moncado).

Zúniga (50 guns).

Girona (50 guns).

Napolitana (50 guns).

Galleys of Portugal under Don Diego de Medrano: 4 ships (each of 50 guns).

Squadron of Xebecs and other ships under Don Antonio de Medoza (including pinnaces): 24 ships (5 to 10 guns).

Complement of the Fleet:

132 ships.

8,766 sailors.

21,556 soldiers.

2,088 convict rowers.

The English Navy comprised:

Ark Royal (flag ship of Lord Charles Howard of Effingham)

Elizabeth Bonaventure

Rainbow (Lord Henry Seymour)

Golden Lion (Thomas Howard)

White Bear (Alexander Gibson)

Vanguard (William Winter)

Revenge (Francis Drake)

Elizabeth (Robert Southwell)

Victory (Rear Admiral Sir John Hawkins)

Antelope (Henry Palmer)

Triumph (Martin Frobisher)

Dreadnought (George Beeston)

Mary Rose (Edward Fenton)

Nonpareil (Thomas Fenner)

Hope (Robert Crosse)

Galley Bonavolia

Swiftsure (Edward Fenner)

Swallow (Richard Hawkins)

Foresight

Aid

Bull

Tiger

New English ‘race’ ship that the Spanish could not catch to board and whose cannon did so much damage to the Armada’s ships: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Tramontana

Scout

Achates

Charles

Moon

Advice

Merlin

Cygnet

Brigandine

George (hoy)

Spy (pinnace)

Sun (pinnace)

Some 150 other coasters, ships and barks.

The 8 fire ships:

Bark Talbot

Hope

Thomas

Bark Bond

Bear Yonge

Elizabeth

Angel

Cure’s Ship.

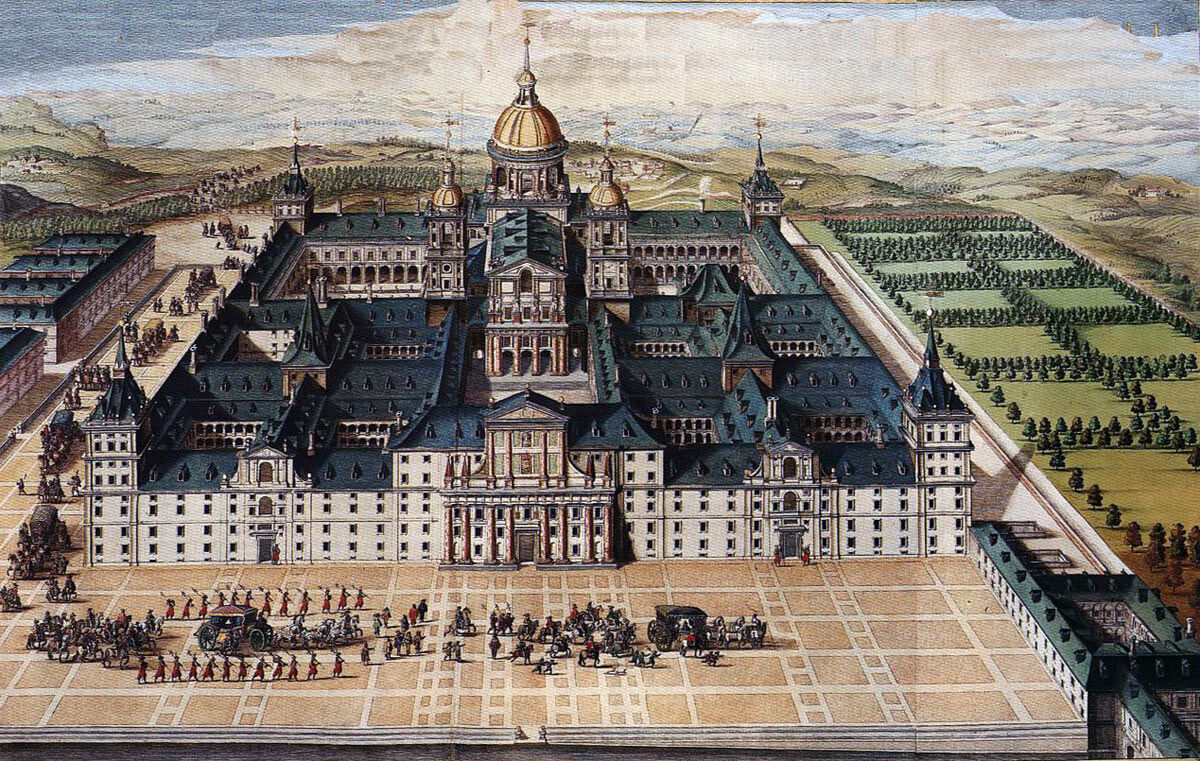

Palace of El Escorial; where Philip II, King of Spain, planned the invasion of England by the Armada: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Glossary:

Hulk or Urcas: a cargo ship (many of the Armada Urcas were from the Baltic ports).

Xebec: a small three masted Mediterranean sailing ship with lateen and square sails.

Galleon: a large sailing ship, square rigged with three or more decks and masts.

Galley: a low, flat ship with banks of oars and limited sails.

Galeas: a galleon with oars.

Pinnace: a small sailing vessel.

Hoy: a small sailing vessel.

‘Armada Portrait’ of Elizabeth I, Queen of England: the rival fleets appear top left: Philip II of Spain planned to depose her, calling her the “Heretic Queen”: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Mary Queen of Scots: executed by Queen Elizabeth I as the focus of Catholic plotting against the English Crown. Mary’s death may have been the final trigger for the launching of the Armada against England: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Account of the Sanish Armada

In 1588 King Philip II of Spain launched his “Armada” to conquer England. Philip devised his plan to invade England by means of the Armada during the period 1570 to 1588, his purpose being to depose the heretic Protestant Queen Elizabeth and reinstate the Catholic religion in England. Philip had been the husband of the Catholic Queen Mary and considered himself King of England until Mary’s death in 1558.

Armada in Spanish simply means “Fleet”. At the time, the invasion fleet was known to the Spanish as the “Fortunate Armada”, a reference to its supposed divine support. The English ironically called it the “Invincible Armada”.

Against her initial inclination, Queen Elizabeth I of England had increasingly become a figurehead for the Protestant struggle in France and the Netherlands, where the Dutch were in revolt against Spanish rule. Her subjects had enraged the Spanish King by raiding his American possessions and even the coastline of Spain itself: Drake sacked Cadiz in 1587 and the Earl of Leicester was leading an English contingent assisting the Dutch revolt in the Netherlands.

The Pope excommunicated Elizabeth and issued an encyclical absolving Catholics from their allegiance to the English Crown, encouraging a series of plots to murder the Queen, who in turn executed the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots in 1587, the focus of the plots. Mary’s execution was the final spur for the Spanish invasion of England.

Reclusive and autocratic, Philip drew up his detailed plans for the “Armada” in the palace of Escorial, north of Madrid, consulting few and listening to little advice.

Philip’s scheme required an enormous fleet of vessels, provided by Spain, his newly acquired kingdom of Portugal and his kingdom of Naples, with such other vessels as could be commandeered, to sail from the Iberian Peninsular to the English Channel and land a substantial Spanish army, partly carried in the Armada, but mainly provided by the Spanish garrison in the Netherlands, on the coast of Kent. Once his army had conquered England, Phillip II would appoint a new king or assume the throne himself.

King Philip II of Spain, the architect of the Armada invasion of England in 1588: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

The King selected an experienced naval veteran, the Marquis de Santa Cruz, to command the Armada. Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, an eminent general and Phillip’s commander against the Dutch rebels, would command the troops brought across the Channel from the Spanish Netherlands.

In Phillip’s enclosed mind there was little difference between his design and the will of God. He was confident, as were his religious advisers, that any inadequacy in his planning would be remedied by divine intervention. 180 priests and monks accompanied the fleet and the crews were enjoined to strict religious observance and conduct; swearing by the men and the presence of women in the ships was particularly proscribed. For the Spanish the Armada was a religious crusade marked by a number of crusader emblems.

Phillip laboured under several misconceptions: one was that the Catholics of England would assist the invading Spanish troops against their own sovereign (in fact the first contingent of troops for the defence of England was raised by a Catholic nobleman; Viscount Montague). Another was that a seaborne invasion could be effected in the presence of a powerful and undefeated English fleet. A third was that the Spanish forces in the Netherlands could get to sea in spite of the numerous and active Dutch fleet. A fourth was that the Duke of Parma was prepared to commit his professional reputation to such a hazardous scheme.

Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, Spanish commander in the Netherlands, who failed to co-operate with the Duke of Medina Sidonia, commander of the Armada: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

King Philip II wrote a stream of written orders and directions to the Marquis de Santa Cruz and the Duke of Parma setting out in detail every aspect of the operation. In accordance with these instructions the Armada assembled at Lisbon and the necessary ammunition and stores were gathered and loaded onto the ships.

In February 1588, with the long gestated plans finally approaching culmination, the Marquis de Santa Cruz died, leaving Philip to find a replacement able to control the disparate and fractious elements within the enormous fleet and its accompanying military force. In the armed forces of 16th Century Spain command could only be effectively exercised by someone of elevated social status, particularly when he would have to work in close co-operation with a nobleman as senior as the Duke of Parma.

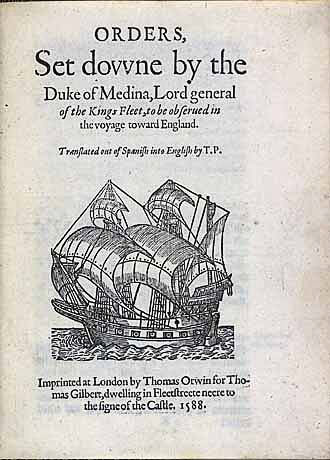

The king’s choice for command fell on Alonzo Perez de Guzman, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat of unimpeachable status but devoid of military or naval experience. A striking feature of the Armada campaign is that Medina Sidonia performed this overwhelming obligation so well in spite of his lack of experience; no doubt due in part to his own character but also to the dedication and expertise of his senior deputies.

Marquis de Santa Cruz: the intended commander of the Armada who died before it could sail: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Ignoring Medina Sidonia’s anguished pleas to be excused the appointment Philip ordered him to take command of the Armada at Lisbon and sail within two weeks.

The Armada comprised squadrons of different types of vessel. The principal naval ships were the great galleons of Portugal, sailing vessels with guns and naval crews.

Philip drafted into the Armada vessels built for Mediterranean conditions: pre-eminent among these were the Neapolitan galleys; long low ships with banks of oars pulled by convicts. 3 of the 4 galleys foundered in the storm in the Bay of Biscay early in the journey north. A compromise vessel intended to have the robustness of the galleon and the manoeuvrability of the galley were the galeases, having masts and oars, of which the Armada had four.

Central to the Armada was the mass of merchant vessels, known as hulks or urcas, converted for war by the addition of higher fore and after castles and a greater complement of guns and carrying the Spanish army with its artillery and baggage. Many of these ships came from the towns of the Hanseatic League in the Baltic. Flagship of the “hulk squadron” was the Gran Grifon from Rostock.

Duke of Medina Sidonia, reluctant commander of the Spanish Armada: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Spanish archives suggest an impressive operation in providing supplies for the expedition, but conceal its inadequacies: stores loaded too early that went bad before the Armada sailed, leaking water barrels, cannon balls of the wrong calibre, food incompetently pickled rotting in the hogsheads. Nevertheless the supplies were sufficient for the fleet to remain at sea for four months, although the ship’s companies that survived to return to Corunna and Santander in late September 1588 arrived near to starvation.

The Armada set sail from Lisbon on 28th May 1588 (British date or Old Style), picking its way out of the Tagus River and working north up the Portuguese coast until it reached Corunna on the north west coast of Spain.

The journey from Lisbon revealed the unwieldy nature of the Armada. The larger galleons, tall bulky floating castles designed for boarding and hand to hand combat, were slow and unweatherly. Many of the merchant vessels were designed for the easier conditions in the Mediterranean; used only to sailing before the wind, dealing with adverse conditions by simply anchoring and waiting for the wind to shift. Several of the ships incorporated banks of oars; suitable for the Mediterranean, but hazardous in the heavy seas of the Atlantic coast. With its various vessels the Armada could sail at an average of 2 ½ knots with a favourable wind.

The Armada took three weeks to sail the 300 miles from Lisbon to Cape Finisterre, a journey in which it was struck by disease, hunger and thirst. On arrival off Corunna, Medina Sidonia grappled with the urge to enter the harbour and seek replenishment of his stores. As he waited a savage and unseasonable storm struck the fleet, dispersing many of the ships as far as the Scilly Isles and wrecking several on the French coast including three of the four galleys. The Armada took refuge in Corunna and spent the next month loading further stores while pinnaces rounded up the vessels scattered across the Bay of Biscay.

Title page to a contemporary English translation of Medina Sidonia’s orders for the Armada. The illustration is of a Portuguese galleon of the Armada: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

During the stay in Corunna Medina Sidonia wrote to King Philip II hinting that the initial leg of the journey from Lisbon had shown the Armada not to be capable of fulfilling the role Philip had assigned to it. Philip took no notice. In mid- July 1588, the Armada sailed for England.

In the meantime Lord Howard of Effingham, Lord High Admiral of England commanding the English Fleet in Plymouth, urged on by the impetuous Drake, had brought his ships into the Bay of Biscay, intent on attacking the Spanish in Corunna harbour. The southerly wind that enabled the Spanish to sail north prevented Howard’s fleet from sailing further south so that, fearful of missing the Armada, Howard returned to Plymouth, to await the arrival of the Spanish ships in the Channel.

After the passage across the Bay of Biscay the Armada arrived off the Scilly Isles on 19th July 1588.

Philip’s orders to Medina Sidonia were that he was to sail up the Channel keeping to the English shore until he reached Margate Point, where he was to rendezvous with the ships from Dunkirk carrying Parma’s army and ensure that Parma landed in England.

Parma understood Philip’s orders to require the Armada to eliminate the English and Dutch Fleets from the Channel and then escort his transports from Dunkirk to England. Parma had no intention of leaving Dunkirk without the protection of the Armada, if he intended to leave at all.

Philip did not appear to appreciate the inconsistency in his plans as to where and how the two commanders were to meet. A staff with a working knowledge of the conditions in the Netherlands would have known of the powerful threat posed by the Dutch navy, making it out of the question to sail transport vessels unescorted from any of the ports available to Parma. At the same time the Armada had not been equipped with pilots familiar with the Netherlands coast so that it was incapable of safely approaching any of Parma’s harbours, situated as they were behind long and dangerous coastal sand banks.

Lord Howard of Effingham, Lord High Admiral of England and commander of the English Fleet against the Armada: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

While Philip’s plan was an extraordinary feat, it was fundamentally unworkable. Parma’s resources were already fully stretched in the Netherlands; ultimately Spain would lose the war against the Dutch revolt. Yet Philip expected Parma to spare sufficient forces to land in England, conquer the country and remove Queen Elizabeth from her throne. The English were already fighting in the Netherlands and Parma had first hand experience of the strength and determination of the country and its commitment to the Protestant faith. Parma could spare 16,000 men for the invasion of England from the war against the Dutch, including reinforcements sent to him from Italy and Spain. Medina Sidonia had orders to provide him with a further 6,000 from the Armada, but Parma doubted that he would fulfill this commitment. Parma knew from information coming across the Channel that the English authorities were mobilising up to 200,000 troops across the country to repel the invasion. King James of Scotland, in spite of being the son of the executed Mary Queen of Scots, was committed to supporting Queen Elizabeth. An invasion of England could only end in disaster and disgrace. While not prepared openly to defy his uncle, the King of Spain, Parma appears to have decided to give minimal co-operation.

On 19th July 1588 Captain Thomas Fleming in the Golden Hinde glimpsed the Armada through the swirling morning mist off the Lizard and raced for Plymouth, Lord Howard’s home port. Fleming came up the channel into Plymouth with the afternoon tide to find Sir Francis Drake playing bowls with his officers on the Ho, high above the harbour. On hearing of Fleming’s sighting Drake insisted on continuing with the game.

Drake playing bowls on Plymouth Ho as the arrival of the Spanish Armada in the Channel is announced: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

That evening with the ebb tide Howard and six of his ships left Plymouth, sailing out into the Channel and heading west, followed the next morning by twenty to thirty more ships.

The Armada had also been seen from the land and the first of the chain of beacons fired, alerting the rest of the kingdom from Devon to Northumbria.

Beacon fires lit across England warning of the Armada’s arrival in the Channel: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

On the night of 20th July 1588 Howard’s and Drake’s ships arrived off the Eddystone Rock where the two fleets caught sight of each other. That night Howard’s vessels worked their way to the west taking the weather gauge from the Spanish.

For the rest of the week the Armada made its ponderous way up the Channel, the vulnerable merchant hulks in the centre of its formation surrounded by the fighting ships, while Howard’s faster and more manoeuvrable vessels attempted to pick off the Spanish with long range gunnery.

The Armada suffered little damage from the English fire, but two ships were lost: Nuestra del Rosario suffered a damaging collision and was forced to fall out of the formation, eventually being taken by Drake’s Revenge, and San Salvador suffered an explosion in her powder store that blew off a substantial section of the ship’s aft. She was evacuated and set adrift until she was captured and towed into Weymouth, still filled with crewmen killed and injured by the blast.

From the moment of his arrival off Cornwall Medina Sidonia pestered the Duke of Parma, with letters delivered to his headquarters in Ghent by the captains of fast pinnaces, pressing Parma to say whether his army was ready to embark and where he would meet the Armada. Parma made no reply.

Philip’s instructions were for the Armada to press on to Margate Head, there to meet the Duke of Parma and his fleet which was to have crossed the Channel. Medina Sidonia was expressly ordered not to deviate from his course or to raid any English towns the Armada might pass.

Contemporary illustration showing the Armada in crescent formation pursued down the Channel by the English Fleet of Lord Howard of Effingham: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

In the absence of confirmation from Parma that he would be at the rendezvous off Margate Head and with increasing evidence of their inability to neutralise the English fleet, Medina Sidonia and his senior officers resolved to meet Parma off the Flanders coast. King Philip had not allowed for this change and the Armada had no pilots familiar with the dangerous and complex coast line of the Low Countries. The only course Medina Sidonia’s senior officers could devise was for the Armada to make for Calais and anchor while contact was made with Parma and his intentions discovered.

Sir Francis Drake, one of Lord Howard’s commanders against the Armada and the captain of the Revenge: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

In the meantime the Armada was pursued and harried up the Channel by Howard’s fleet until on 23rd July 1588 the Armada reached Portland Bill where the wind veered to the North East, giving the weather gauge to the Spanish and enabling them to turn and attack the pursuing English ships. A spirited but confused battle ensued. At one point in the engagement Lord Howard ordered a number of ships to follow him in a line ahead attack, reserving fire until close quarters had been reached; the vessels being Victory, Elizabeth, Golden Lion, Mary Rose, Dreadnought and Swallow. It seems unlikely that this attack developed fully.

Spanish Armada June to September 1588: the decisive action off Calais; the English attack at midnight led

by the eight fire ships that forced the Spanish to cut their cables and escape east up the Channel

The English ships inflicted little damage on the Armada, in spite of firing off much of their ammunition, probably because they did not stand in close enough. The Spanish were unable to achieve the essential ingredient for their style of naval warfare, that is by coming alongside the enemy, grappling the ships together and capturing by boarding; the English ships being too nimble. The battle ended inconclusively.

On the next day the Spanish contemplated a turn into the Solent, approaching around the east tip of the Isle of Wight, but the wind was not correct and they resumed their progress up the Channel.

On 27th July 1588 the Armada anchored off Calais. None of the Spanish officers were happy at the arrangement, but there was no question of taking the Armada’s large ships on up the Channel without local pilots, with the near certainty of grounding on the sandbars that marked the coast to the East. Medina Sidonia sent further urgent messages to Parma in an attempt to discover his intentions and for the first time received a reply; Parma was not yet ready.

Spanish Armada June to September 1588: Battle of Gravelines on 28th July 1588; the English attack at midnight led by the eight fire ships that forced the Spanish to cut their cables and escape east up the Channel

The Spanish Fleet anchored in a tight knit group to reduce the danger of being picked off by Howard’s marauding ships. All were aware that this rendered the Armada particularly vulnerable to attack by fire ships and on the next night that was exactly the tactic that was deployed against them. At midnight on 28th July 1588 eight vessels filled with combustible material and manned by skeleton crews sailed down on the Armada. As they approached the anchored fleet the eight ships burst into flames.

Battle of Gravelines on 28th July 1588: English fire ships advance on the Spanish Armada anchored offshore at Calais, before the crews set them ablaze: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Alert to the danger of such an attack the Spanish had posted picquet vessels that attempted to tow the fire ships into shallow water where they could be beached until they burnt out, but without success, other than in one instance. The Armada was forced to apply the reserve order; cut anchor cables and sail away to the east as quickly as possible (the loss of the main anchors in this way was to have devastating consequences later when ships attempted to anchor off the coasts of Scotland and Ireland in fierce storms but were driven onto the shore).

Battle of Gravelines on 28th July 1588: at which the English Fleet dispersed the Spanish Armada and forced it into the North Sea: Spanish Armada June to September 1588: picture by Philip James de Loutherbourg

With dawn, Medina Sidonia found the Armada scattered and the English fleet in full attack. Other Spanish ships beat back to join the flagship San Martin and a fierce battle took place, known as the Battle of Gravelines from the port on the coast.

This time the English closed with the Spanish ships and used their guns at close range, the shots penetrating the wooden hulls of the Spanish ships frequently below the water line. The Spanish inflicted little damage on the English ships.

Battle of Gravelines on 28th July 1588: at which the English Fleet dispersed the Spanish Armada and forced it into the North Sea: Spanish Armada June to September 1588: picture by Harold Wyllie

Beaten in the battle the Spanish were carried up into the North Sea; two ships sunk and most of the remainder damaged by gunfire with high casualties among the crew and soldiery.

Although the tactical results of the fighting were not decisive the Armada was strategically defeated. It was no longer feasible, if it ever had been to mount a military invasion of England. The only course open to the Armada was to return home.

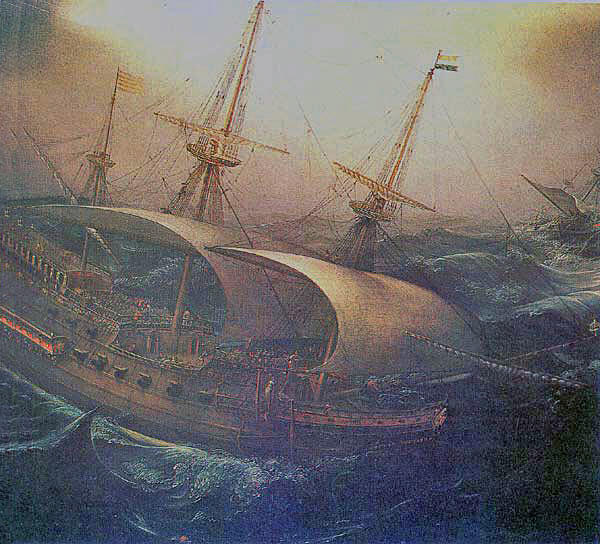

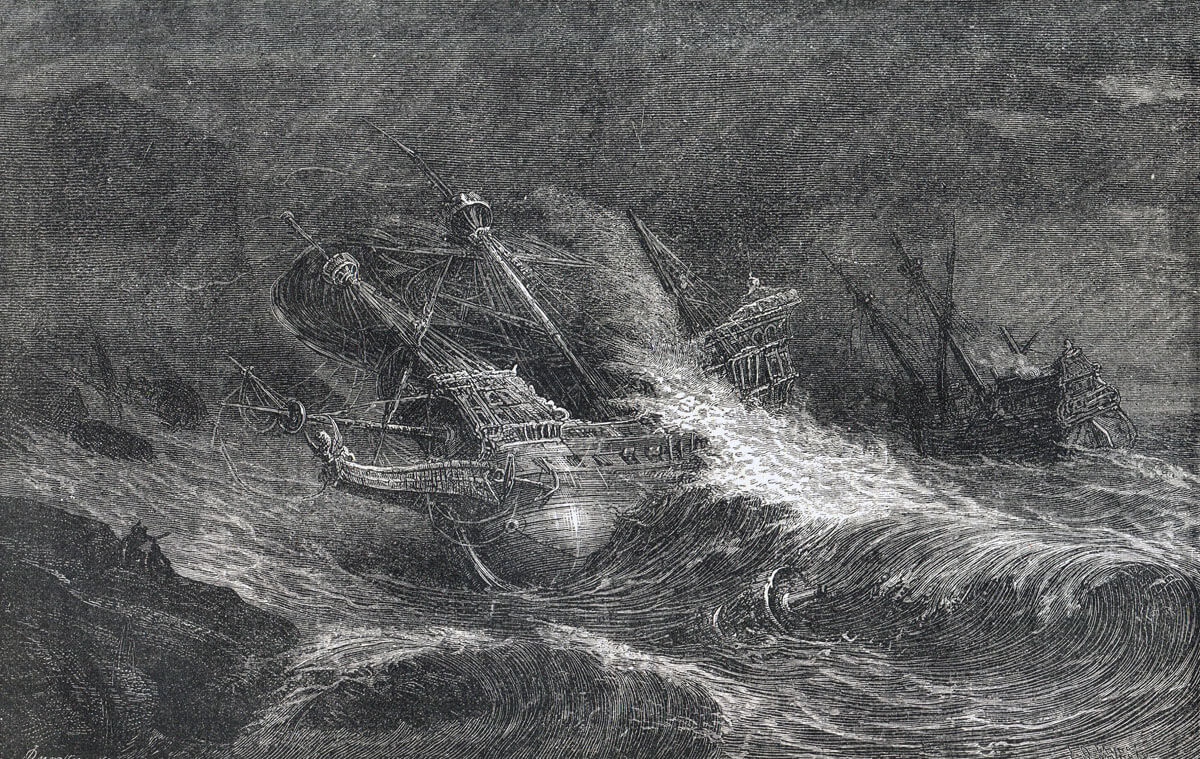

The prevailing winds were westerly and Howard’s fleet lay in the mouth of the Channel. Unable to retrace his steps Medina Sidonia was forced to order his fleet to sail for home by the “North About” route round the tip of Scotland and down the west coast of Ireland; a daunting prospect for a fleet short of food and water, with many of the ships severely battle damaged and unsuited in design for such inhospitable waters. It was a cruel addition that the storms from the Atlantic were that year unseasonably bad.

The Spanish possessed no charts that could help them navigate the route around Scotland and Ireland. Medina Sidonia gave his captains sailing instructions running to just a few lines with the most cursory of directions.

Spanish ships lost in the Spanish Armada campaign:

Ships of the Armada storm tossed on the route “North About” round the Northern tip of Scotland: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

Around half of the ships in the Spanish Armada were sunk in the storms that raged around Scotland and Ireland in the autumn of 1588.

- El Gran Grifin was wrecked on Fare Isle to the North of Orkney.

- San Marcos was wrecked on the Irish coast.

- San Felipe and San Mateo were grounded in the Netherlands and captured by the Dutch.

- Florencia was scrapped after her return being beyond repair.

- El Gran Grin was wrecked off the Irish coast and the surviving crew hanged by English troops.

- La Maria Juan sank during the Battle of Gravelines.

- San Juan was wrecked off the coast of Ireland.

- La Trinidad disappeared and is presumed to have sunk in the Atlantic.

- San Juan Bautista sailed into Blasket Sound off the south west coast of Ireland and was finally scuttled by Admiral Recalde.

- Urca Duquesa Santa Ana was wrecked off the coats of Ireland.

- Santa Ana reached San Sebastian on the north coast of Spain but blew up.

Santa Maria de la Rosa foundering in Blasket Cove off the South West coast of Ireland. Only one member of the crew survived, a sixteen year old Italian boy name Giovanni. Giovanni was interrogated by English officials and hanged: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

- Santa Maria de La Rosa was wrecked in Blasket Sound on 11th September 1588.

- San Estéban foundered off the Clare coast of Ireland. The surviving crew were hanged.

- La Lavia: this ship carrying the Armada Judge Advocate General was believed to have foundered off the Irish coast.

- La Rata Encoronada went aground and was burnt in Blacksod Bay, County Mayo.

- San Juan de Sicilia blew up in Tobermory Bay in Scotland.

- La Trinidad Valencera foundered in Kinnagoe Bay, Donegal.

- La Anunciada was scuttled in the Shannon estuary.

- Juliana sank off Donegal. Crew survivors are believed to have settled in Ulster.

- Falcon Blanco Mayor: a Hamburg ship commandeered by the Spanish was taken by Drake in the Channel returning to her home port.

- Castillo Negro sank off Ireland.

- Barca de Amburg sank off Ireland although her crew were taken on board other ships that in turn sank.

- San Pedro Mayor was wrecked on the Devon coast after sailing “North About”.

- Falcon Blanco Mediano was wrecked off Connemara. Most of the surviving crew were hanged.

- Santiago foundered off Ireland

- San Lorenzo ran aground off Calais after the fire ship attack.

- Patrona reached Le Havre after the North About journey near disintegration.

- Girona was wrecked off Antrim.

- Princesa, galley, was wrecked off Bayonne.

- Diana, galley, was wrecked off Bayonne.

The main body of the Armada reached Corunna on 11th September 1588, comprising less than half of the ships that had sailed north in late June. Most of the ships were on starvation rations and had run out of water. Several were so badly damaged as to be scrapped. The remaining ships to survive straggled back to the north coast of Spain through October 1588.

Casualties in the Spanish Armada campaign: Contemporary Spanish record state that 65 ships survived the Armada and 65 were lost. Of the lost 41 were major ships. Of the 30,000 soldiers and crew in the Armada probably 20,000 died during the voyage; of wounds, by execution (by the English in Ireland), but mostly of starvation and disease. They continued to die after the Armada reached Spanish ports.

It is said that there was no noble family in Spain that did not lose a son in the Armada.

The Armada carried a large number of horses and mules for the invasion force. These animals were put over the side in the North Sea as it was considered there was insufficient water for the journey home. An English ship later saw the mass of animals swimming in the sea.

English casualties were slight. No ship was lost other than the eight fire ships.

Follow-up to the Spanish Armada campaign:

The English admirals remained fearful that the Armada would return from the North Sea and the fleet remained on alert for some six weeks.

On hearing news of the disaster Philip II vowed that he would continue his attempts to remove Elizabeth from the throne of England.

The Duke of Medina Sidonia returned to his estates, carried during the long journey in a litter. He was banned from attending at court.

Recalde, his redoubtable second in command was carried from his ship and died soon afterwards, refusing to see family or friends.

Anecdotes and traditions of the Spanish Armada campaign:

- Both Spanish and English ships seem to have flown the red cross on a white background; the Spanish because Philip II considered the Armada to be a crusade to remove a heretic queen and the cross was the crusader emblem; the English because the cross of St George was the national emblem.

- Examination of the wrecks off Ireland showed the Mediterranean merchant ships to have been slightly built compared with ships of war or even Atlantic going merchant ships. The sole advantage of these vessels was their greater size and availability. They could only sail before the wind and the bombardment they suffered in the Channel made the chances of their survival during the terrible journey “North About” slight in the extreme.

- Pope Sixtus V pledged a million ducats as his contribution to the cost of removing the heretic Queen Elizabeth from her throne. Cannily Sixtus V said he would pay the money once the Spanish landed in England.

- Among the many foreign vessels commandeered by the Spanish for the Armada was the Florencia, a galleon belonging to the Duke of Tuscany. The Florencia, on her maiden voyage to the East Indies put into Lisbon where she was seized for service in the Armada. By the time the Florencia returned from the voyage “North About” she was ruined beyond repair.

- In case any member of the Armada’s crews missed the religious context of the expedition Philip II set the watchwords for the fleet as: Sunday- Jesus, Monday- Holy Ghost, Tuesday- Most Holy Trinity, Wednesday- Santiago, Thursday- The Angels, Friday- All Saints and Saturday- Our Lady.

- As part of the mobilisation of the South of England, the Earl of Leicester, Elizabeth’s favourite and erstwhile English commander in the Netherlands, gathered 5,000 troops at Tilbury in the Thames Estuary. The Queen reviewed Leicester’s force. Elizabeth is reported to have spoken to her officers and said “… I may have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart of a King of England.”

- A startling feature of the “Spanish Armada” was the contrast in treatment Spanish prisoners received from the English depending on where they were captured. Spanish officers and crew taken in the Channel or wrecked on the Scottish coast seem to have been treated with consideration and repatriated as soon as Parma sent a ship to collect them. On the other hand those taken by the English in Ireland after escaping from their foundering ships were all executed, other than very senior officers. The explanation, such as it is seems to have been that the English Lord Deputy in Ireland, Sir William Fitzwilliam feared that the Spanish would arm and lead an Irish revolt, which to some extent is what did happen. Fitzwilliam was never sure whether vessels coming ashore were from the Armada or a new Spanish descent specifically aimed at fomenting revolt in Ireland. Fitzwilliam’s instruction to his subordinates along the coast of Ireland stated: “… we authorise you to make inquiry by all good means, both by oath and otherwise, to take all the hulls of ships, stores, treasures, etc. into your hands and to apprehend and execute all Spaniards found there of what quality so ever. Torture may be used in prosecuting this inquiry.”

- When the Armada was in the North Sea two ship’s captains were arrested and sentenced to death for failing to keep station on the flagship, a capital offence in the Spanish navy. One was hanged and the other, Francisco de Cuellar of the San Pedro was reprieved by Medina Sidonia only to be ship wrecked on the coast of Ulster several days later while still in the custody of the Judge Advocate General, who sadly was drowned. De Cuellar survived, thanks to the assistance of a local Irish chief whose castle he defended against the English. De Cuellar crossed to Scotland where he and some one hundred and twenty wrecked Spaniards were collected by a ship sent from the Netherlands by the Duke of Parma. This ship was attacked by the Dutch and wrecked on the coast of Flanders, leaving De Cuellar one of three survivors to return to Spain.

- Captain Alonso de Leiva abandoned his stranded ship, La Rata Encoronada in Blacksod Bay, County Mayo and after capturing a small Irish castle with his crew marched across country to join the Urca Duqesa Santa Ana, moored in the next bay. De Leiva was wrecked for a second time off the coast of Donegal when the Santa Ana was driven ashore by the storms. Again de Leiva and his men took a castle and held it against the English, leaving it to join the galeas Girona. Girona set sail for Spain only in her turn to be smashed on the Antrim coast with complete loss of life, including the intrepid de Leiva.

- The West Highland terrrier breed is said to have been bred from dogs that came ashore with the wreck of Spanish Armada ships on the coast of West Scotland. The “Westies” were part of the ship’s complement having the task of keeping down the rat population.

- Several Armada ships sank around the Orkney Islands off the north east coast of Scotland. Spanish seamen survived the wrecks to settle on the Islands where their descendants are to this day known as the ‘Dons’. Also surviving the wrecks were a number of chickens, the forbears of an island breed still known as ‘Armada chickens’.

- Another animal tradition is that the tail-less Manx cats came from a wrecked Spanish Armada ship. The vessel is said to have foundered on Spanish Rock off the coast of the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea, the cats swimming ashore and becoming an established breed on the island. The cats originally came on board the ship in the Far East.

- After the North About journey five Armada ships came into Blasket Sound off the South West coast of Ireland in early September 1588: San Juan, Juan Martinez de Recaldo’s ship, San Juan Bautista, Santa Maria de La Rosa, a second San Juan Bautista and an unidentified smaller ship. Recaldo, remarkably, led the first two ships on 11th September 1588 through a gap in the reef little wider than the ships themselves, having sailed the coast some years before on an earlier Spanish incursion to Ireland. The two ships remained in the Sound for some days shadowed by English troops on the coast. The Santa Maria suddenly appeared, plunging through the reef and sank with no survivors. Later the second San Juan Bautista, in a near derelict condition and the unknown frigate arrived. Recaldo refused to leave the sound until he had removed as many of the guns from the second San Juan Bautista as he could and set the ship on fire. Both the San Juan and the first San Juan Bautista reached Spain.

- Eight crewmen sent ashore from the San Juan to find a water source were captured by the English and interrogated through an escaped oarsman from the wrecked Portuguese galley Diana called David Gwynne. Gwynne also interrogated the sole survivor from the Santa Maria, a sixteen year old boy called Giovanni, the son of an Italian pilot. It seems likely that Gwynne deceived the English authorities as to his language skills. All the captured crew were hanged after their interrogation.

- On 10th September 1588 the San Estéban and another Spanish ship came ashore off the coast of County Clare. The Sheriff of Clare, Boetius Clancy, acting on the instruction of the Lord Deputy executed all the survivors in an area known since that day as the Field of Hangings. From that time, every seven years a service has been held at a church in Spain formally to curse the name of Boetius Clancy the Sheriff of Clare for his murder of the Spanish prisoners.

- Ghosts of members of the crew from the wrecked Spanish Armada ship San Esteban, hanged by Boetius Clancy, Sheriff of Clare after they had been captured and tortured are said to haunt the beach below Doonagore Castle on the coast of County Clare.

- On 15th September 1588 three Spanish ships were wrecked on the Sligo coast; one thousand bodies were counted on the single stretch of beach.

- Several of the Spanish ships reached Spain in a sinking condition; one urca going down in harbour. The galleon Santa Ana exploded and sank at Santander, while another ship ran aground, the crew too exhausted to take in the sails and anchor. Thousands of Spanish crew died of disease and exhaustion in the months following the return of the Armada.

- The Falcon Mayor, a hulk from Hamburg, returned to her home town and resumed normal maritime life. In 1589 she was recognized by Drake sailing in the Channel and taken.

- The Armada campaign was enormously costly for Spain. Philip II was forced to take out large loans and increase taxation significantly to meet the expenses including claims for compensation from owners of foundered ships. The Armada campaign was expensive for England as well.

- Philip II ordered two enquiries into the conduct of officers of the Armada in an attempt to establish the reasons for its failure.

- The religious authorities in Spain were at a loss to explain why God allowed the Armada to fail: it was finally decided the reason was that the Spanish had taken too long to evict the Moors from Granada in the previous century.

Queen Elizabeth reviews the Earl of Leicester’s troops at Tilbury when she made her renowned speech: Spanish Armada June to September 1588

References for the Spanish Armada campaign:

The literature on the Armada is extensive. A sample:

The Voyage of the Armada by David Howarth.

The Defeat of the Spanish Armada by Garrett Mattingley.

Full Fathom Five: Wrecks of the Spanish Armada by Colin Martin.

The previous battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Pinkie

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Edgehill

Spanish Armada charts published 1590: 2 Armada and English Fleet off Plymouth 30th and 31st July 1588

Spanish Armada charts published 1590: 3 English ships attack the Armada off Plymouth on 31st July 1588

Spanish Armada charts published 1590: 4 English fleet pursues the Armada up the Channel, 31st July to 1st August 1588

Spanish Armada charts published 1590: 5 Action between the English Fleet and the Armada off Portland Bill on 1st and 2nd August 1588

Spanish Armada charts published 1590: 6 Armada Charts 6 English ships attack the Armada between Portland Bill and the Isle of Wight on 2nd and 3rd August 1588

Spanish Armada charts published 1590: 7 English fleet attacks the Armada off the Isle of Wight on 4th August 1588

Spanish Armada charts published 1590: 8 English Fleet and the Armada sail up the Channel to Calais on 4th to 6th August 1588

Spanish Armada charts published 1590: 9 Eight English fire ships attack the Armada on 7th August 1588

Spanish Armada charts published 1590: 10 English Fleet attacks the Armada at Gravelines on 8th August 1588