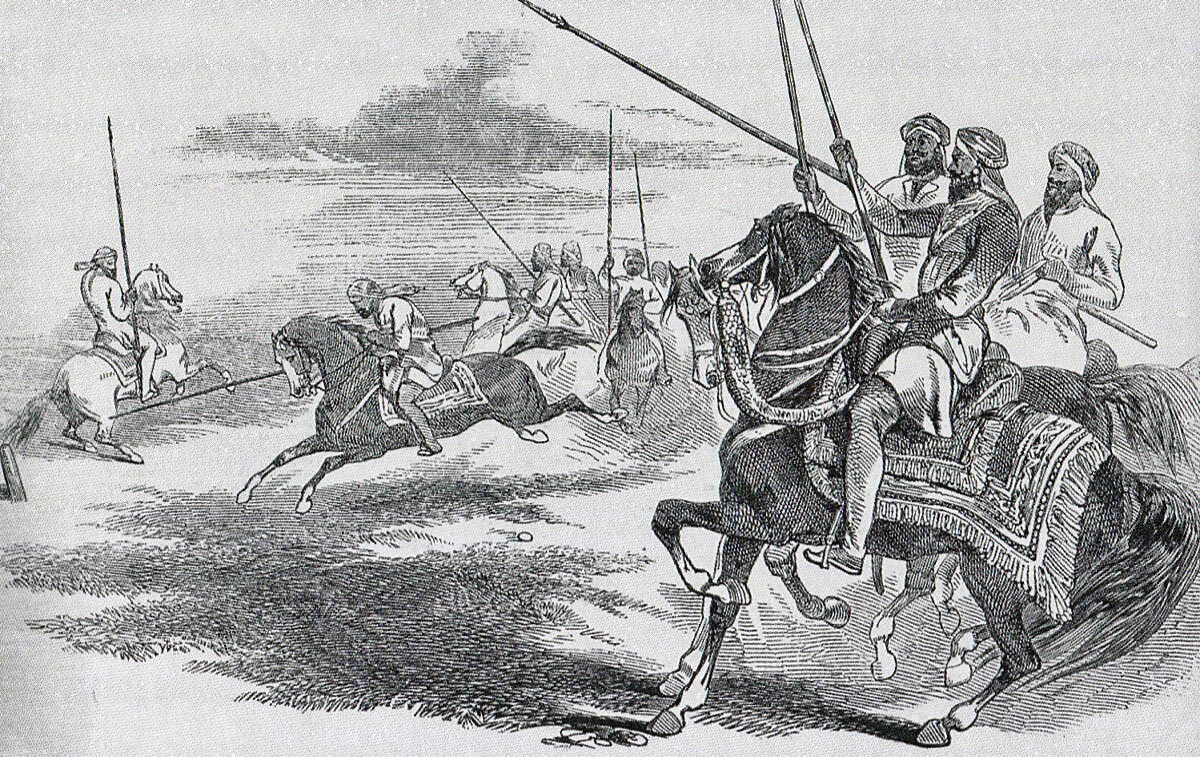

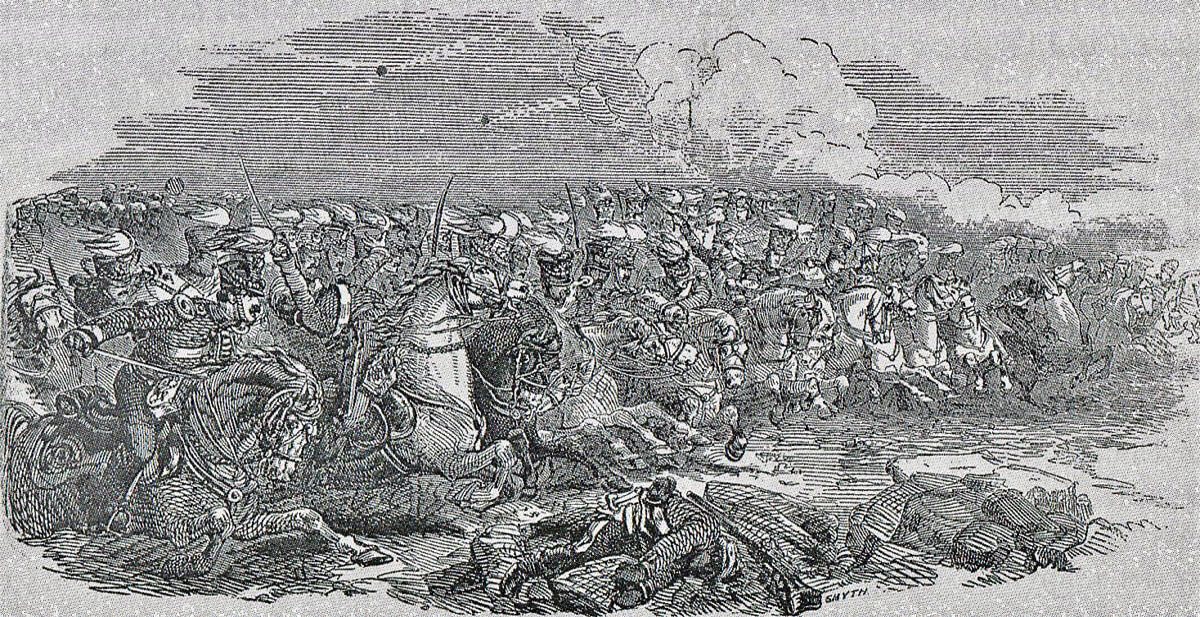

The savage skirmish on the banks of the Chenab River on 22nd November 1848 in the Second Sikh War, that led to the deaths of General Cureton and Colonel Havelock of the 14th Light Dragoons

14th Light Dragoons charging at the Battle of Ramnagar on 22nd November 1848 during the Second Sikh War

The previous battle, from the First Sikh War, is the Battle of Sobraon

The next battle of the Second Sikh War is the Battle of Chillianwallah

Battle: Ramnagar

War: Second Sikh War.

Date of the Battle of Ramnagar: 22nd November 1848.

Place of the Battle of Ramnagar: In the Punjab in the north-west of India.

Combatants at the Battle of Ramnagar: British troops and Indian troops of the Bengal Presidency against Sikhs of the Khalsa, the army of the Punjab.

Commanders at the Battle of Ramnagar: Major General Sir Hugh Gough against Shere Singh.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Ramnagar: 12,000 British and Bengali troops and 60 guns against 20,000 Sikhs and 50 guns.

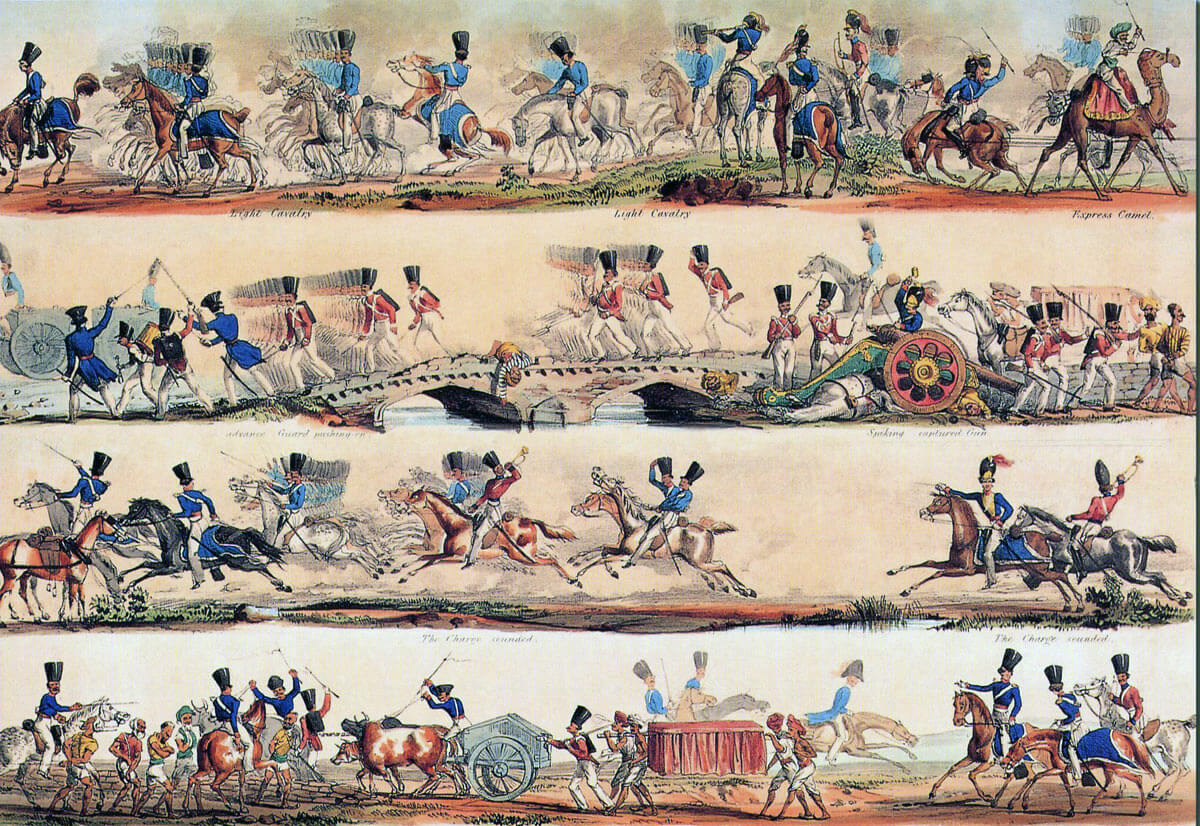

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Ramnagar (this section is the same in each of the battles of the Sikh Wars):

The two wars fought between 1845 and 1849 between the British and the Sikhs led to the annexation of the Punjab by the British East India Company, and one of the most successful military co-operations between two races, stretching into a century of strife on the North West Frontier of British India, the Indian Mutiny, Egypt and finally the First and Second World Wars.

The British contingent comprised four light cavalry regiments (3rd, 9th, 14th and 16th Light Dragoons- the 9th and 16th being lancers) and twelve regiments of foot (9th, 10th, 24th, 29th, 31st, 32nd, 50th, 53rd, 60th, 61st, 62nd and 80th regiments).

The bulk of General Gough’s ‘Army of the Sutlej’ in the First Sikh War and ‘Army of the Punjab’ in the Second Sikh War comprised regiments from the Bengal Presidency’s army: 9 regular cavalry regiments (the Governor-General’s Bodyguard and 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th and 11th Bengal Light Cavalry), 13 regiments of irregular cavalry (2nd, 3rd, 4th, 7th to 9th and 11th to the 17th Bengal Irregular Cavalry), 48 regiments of foot (1st to 4th, 7th, 8th, 12th to 16th, 18th, 20th, 22nd, 24th to 27th, 29th to 33rd, 36th, 37th, 41st to 54th, 56th, 59th, 63rd and 68th to 73rd Bengal Native Infantry), horse artillery, field artillery, heavy artillery and sappers and miners.

Arrival in India of the 14th King’s Light Dragoons in 1842: Battle of Ramnagar on 22nd November 1848 during the Second Sikh War

The Bombay presidency contributed a force that marched in from Scinde, in the west, and gave considerable assistance at the Siege of Multan; the 19th Bombay Native Infantry gaining the title of the Multan Regiment for its services in the siege, a label still held by its Indian Army successor.

A Bombay brigade under Brigadier Dundas joined General Gough’s army for the final battle of the Second Sikh War at Goojerat, where the two regiments of Scinde Horse, Bombay Irregular Cavalry, particularly distinguished themselves. The brigade comprised: 2 regiments of Scinde Horse, 3rd and 19th Bombay Native Infantry and Bombay horse artillery and field artillery.

Each of the three presidencies, in addition to their native regiments, possessed European infantry, of which the 1st Bengal (European) Infantry, 2nd Bengal (European) Light Infantry and 1st Bombay (European) Fusiliers took part in the Sikh Wars.

Other corps fought under the British flag, such as the Shekawati cavalry and infantry and the first two Gurkha regiments: the Nasiri Battalion (later 1st Gurkhas) and the Sirmoor Battalion (later 2nd Gurkhas).

General Gough commanded the British/Indian army at 6 of the 7 major battles (not the Battle of Aliwal). An Irishman, Gough was immensely popular with his soldiers, for whose welfare he was constantly solicitous. The troops admired Gough’s bravery, in action wearing a conspicuous white coat, which he called his ‘Battle Coat’, so that he might draw fire away from his soldiers.

Gough’s tactics were heavily criticised, even in the Indian press in letters written by his own officers. At the Battles of Moodkee, Sobraon and Chillianwallah, Gough launched headlong attacks, considered to be ill-thought out by many of his contemporaries. Casualties were high and excited concern in Britain and India. By contrast, Gough’s final battle, Goojerat, which decisively won the war, cost few of his soldiers their lives and was considered a model of care and planning.

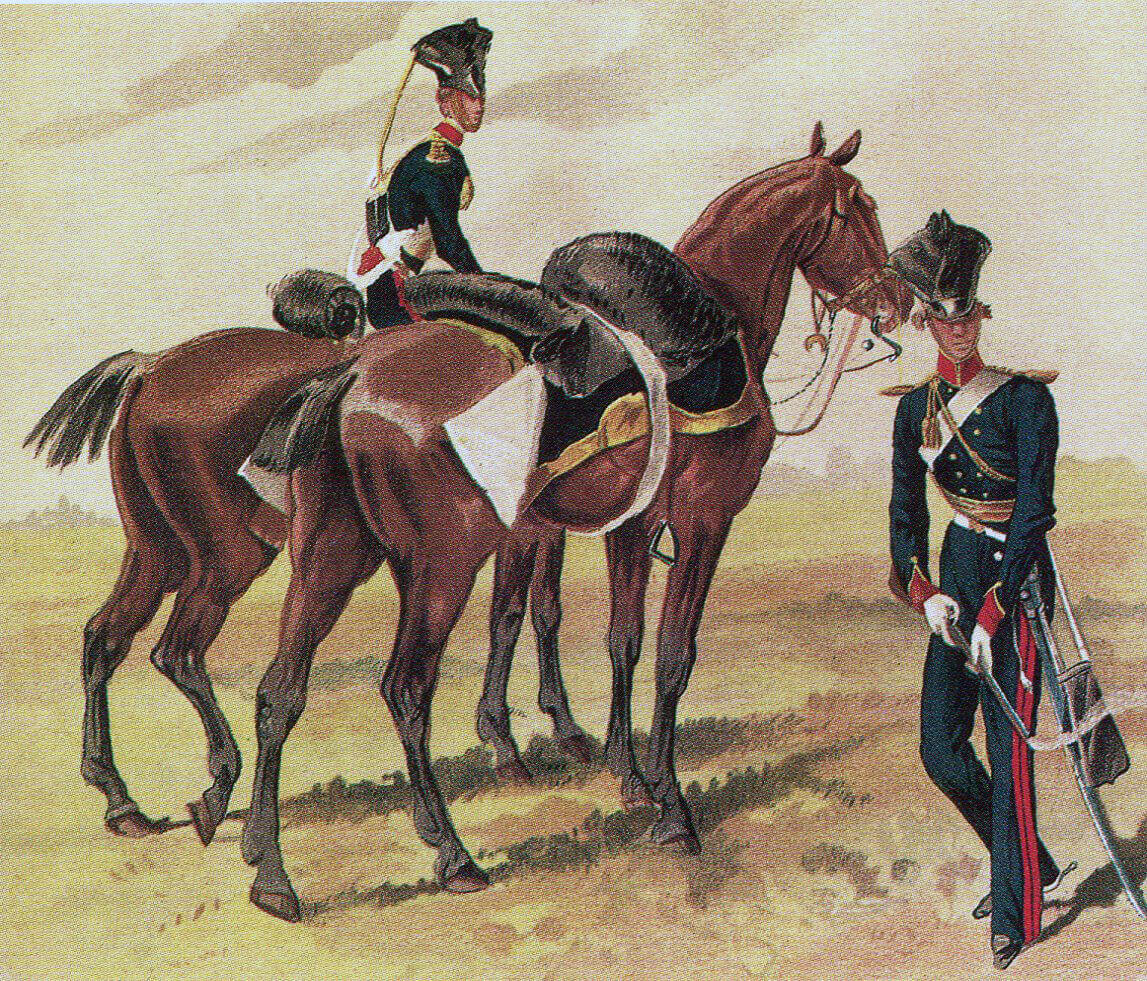

Every battle saw vigorous cavalry actions, with HM 3rd King’s Own Light Dragoons and HM 16th Queen’s Royal Lancers particularly distinguishing themselves. The British light cavalry wore embroidered dark blue jackets and dark blue overall trousers, except the 16th who bore the sobriquet ‘the Scarlet Lancers’ for their red jackets. The headgear of the two regiments of light dragoons was a shako with a white cover; the headgear of the lancers the traditional Polish tschapka.

HM regiments of foot wore red coats and blue trousers with shakos and white covers.

The Bengal and Bombay light cavalry regiments wore pale blue uniforms. The infantry of the presidency armies wore red coats and peak less black shakos.

The weapons for the cavalry were the lance for the lancer regiments and sword and carbine for all; the infantry was armed with the Brown Bess musket and bayonet.

Commands in the field were given by the cavalry trumpet and the infantry drum and bugle.

In the initial battles, the Sikh artillery outgunned Gough’s batteries. Even in these battles and in the later ones, the Bengal and Bombay horse and field artillery were handled with great resource and were a major cause of Gough’s success.

Many of the more senior British officers had cut their military teeth in the Peninsular War, and at the Battle of Waterloo: Gough, Hardinge, Havelock of the 14th Light Dragoons, Cureton, Dick, Thackwell and others. Many of the younger men would go on to fight in the Crimea and the Indian Mutiny.

The Sikhs of the Punjab looked to the sequence of Gurus for their spiritual inspiration, and had established their independence, fiercely resisting the Moghul Kings in Delhi and the Muslims of Afghanistan. The Sikhs were required by their religion to wear the ‘five Ks’, not to cut their hair or beard and to wear the highly characteristic turban, a length of cloth in which the hair is wrapped around the head.

The Maharajah of the Punjab, Ranjit Singh, whose death in 1839 ended the Sikh embargo on war with the British, established and built up the powerful Sikh Army, the ‘Khalsa’, over the twenty years of his reign. The core of the ‘Khalsa’ was its body of infantry regiments, equipped and trained as European troops, wearing red jackets and blue trousers. The Sikh artillery was held in high esteem by both sides. The weakness in the Sikh army was its horse. The regular cavalry regiments never reached a standard comparable to the Sikh foot, while the main element of the mounted arm comprised clouds of irregular and ill-disciplined ‘Gorcharras’.

The traditional weapon of the Sikh warrior is the ‘Kirpan’, a curved sword kept razor sharp and one of the ‘five Ks’ a baptised Sikh must wear. In battle, at the first opportunity, many of the Sikh foot abandoned their muskets and, joining their mounted comrades, engaged in hand to hand combat with sword and shield. Horrific cutting wounds, severing limbs and heads, were a feature of the Sikh Wars, in which neither side gave quarter to the enemy.

It had taken the towering personality of Ranjit Singh to control the turbulent ‘Khalsa’, he had established. Ranjit Singh’s descendants found the task beyond them and did much to provoke the outbreak of the First Sikh War, in the hope that the Khalsa would be cut down to size by the armies of the British East India Company. The commanders of the Sikh armies in the field rarely took the initiative in battle, preferring to occupy a fortified position and wait for the British and Bengalis to attack. In the opening stages of the war there was correspondence between Lal Singh and the British officer, Major Nicholson, suggesting that the Sikhs were being betrayed by their commander.

Pay in the Khalsa was good, twice the rate for sepoys in the Bengal Army, but it was haphazard, particularly after the death of Ranjit Singh. Khalsa administration was conducted by clerks writing in the Persian language. In one notorious mutiny over pay, Sikh soldiers ran riot looking for anyone who could, or looked as if they could, speak Persian, and putting them to the sword.

The seven battles of the war and the siege of the city of Multan were hard fought. Several of the battle fields were wide flat spaces broken by jungly scrub, from which the movement of large bodies of troops in scorching heat raised choking clouds of dust. As the fighting began, the dust clouds intermingled with dense volumes of musket and cannon smoke. With the thunder of gunfire and horses’ hooves, the battle yells and cries of the injured, the battles of the Sikh Wars were indeed infernos.

Winner of the Battle of Ramnagar: As Gough’s aim was to drive the Sikhs back across the Chenab River and he achieved this, it could be said that the action was successful. On the other hand, the result was the death of Brigadier Cureton, probably the best cavalry general in India, and many other men, including the commanding officer of the 14th Light Dragoons, Lieutenant Colonel Havelock.

Bengal Light Cavalry: Battle of Ramnagar on 22nd November 1848 during the Second Sikh War: print by Ackermann

British and Indian Regiments at the Battle of Ramnagar:

British Regiments:

HM 3rd King’s Own Light Dragoons, now the Queen’s Royal Hussars.

HM 9th Queen’s Royal Light Dragoons (Lancers), now the 9th/12th Royal Lancers.

HM 14th the King’s Light Dragoons, now the King’s Royal Hussars.

HM 24th Foot, later the South Wales Borderers and now the Royal Welsh Regiment.

HM 29th Foot, later the Worcestershire Regiment and now the Worcestershire and Sherwood Foresters Regiment.

HM 61st Foot, later the Wiltshire Regiment and now the Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Regiment.

Bengal Army:

1st Bengal Light Cavalry.

5th Bengal Light Cavalry.

6th Bengal Light Cavalry.

9th Bengal Light Cavalry.

2nd European Light Infantry.

6th Bengal Native Infantry.

15th Bengal Native Infantry.

20th Bengal Native Infantry.

25th Bengal Native Infantry.

30th Bengal Native Infantry.

31st Bengal Native Infantry.

36th Bengal Native Infantry.

45th Bengal Native Infantry.

56th Bengal Native Infantry.

69th Bengal Native Infantry.

70th Bengal Native Infantry.

Cavalry:

All the regular Bengal cavalry regiments that fought at Sobraon ceased to exist in 1857.

Infantry:

2nd Bengal (European) Light Infantry, from 1861 102nd Light Infantry, from 1880 the Munster Fusiliers, disbanded in 1922.

31st Bengal Native Infantry in1861 became the 2nd Bengal Light Infantry, in 1903 2nd (Queen’s Own) Rajput Light Infantry, in 1922 1st (Queen Victoria’s Own) Light Infantry Battalion 7th Rajput Regiment and in 1947 became 4th Battalion the Brigade of the Guards of the Indian Army.

70th Bengal Native Infantry from 1861 11th Bengal Native Infantry, from 1903 11th Rajputs, from 1922 5th Battalion 7th Rajput Regiment and from 1947 5th Battalion, the Rajput Regiment of the Indian Army.

The remaining Bengal infantry regiments that fought at Ramnagar ceased to exist in 1857.

Ramnagar is not a battle honour for British or Bengal regiments. It is subsumed in the general battle honour of “Punjab 1848-49”.

Order of Battle of the Army of the Punjab at the Battle of Ramnagar:

Cavalry Division: Brigadier General Cureton.

1st Brigade: Brigadier White; HM 3rd Light Dragoons, HM 14th Light Dragoons, 5th and 8th BLC.

2nd Brigade: Brigadier Pope; HM 9th Lancers, 1st and 6th BLC.

1st Infantry Division: General Gilbert.

1st Brigade: Brigadier Mountain; HM 29th Foot, 30th and 56th BNI.

2nd Brigade: Brigadier Godby; 2nd European LI, 31st and 70th BNI.

2nd Infantry Division: General Thackwell.

1st Brigade: Brigadier Pennycuick; HM 24th Foot, 25th and 45th BNI.

2nd Brigade: Brigadier Hoggan; HM 61st Foot, 6th and 36th BNI.

3rd Brigade: Brigadier Penny; 15th, 20th and 69th BNI.

Six horse batteries: Lane, Christie, Huish, Warner, Duncan and Fordyce.

Three field batteries: Dawes, Kenleside and Austin.

Two heavy batteries.

14th King’s Light Dragoons: Battle of Ramnagar on 22nd November 1848 during the Second Sikh War: print by Ackermann

Account of the Battle of Ramnagar:

The First Sikh War ended in 1846 with the Treaty of Lahore, leaving the Punjab dependent on the British, but stopping short of outright annexation. The treaty required that the Khalsa, the Sikh army, be reduced in size and number of guns, although it is doubtful that this was complied with. The Sikh government agreed to pay a large sum in reparations to the British, with compliance secured on Kashmir. When the Sikhs found themselves unable to pay, Kashmir became forfeit, to the dismay of the British who lacked the resources to occupy the remote Himalayan province.

Difficulties over Kashmir were followed by the killing of two British officers by Sikh soldiers in Multan in April 1848. A force of Sikh troops moved against the rebels commanded by a British officer, Herbert Edwardes, but the Sikhs began to desert, and it became apparent that the rebels were acting with the encouragement of the Sikh rulers.

Edwardes intended to conduct a siege of Multan, while Major General Sir Hubert Gough, the British commander-in-chief in the First Sikh War, gathered his forces, this time on the River Chenab, further north than the Sutlej River, the scene of the fighting in the first war.

14th King’s Light Dragoons at the Battle of Ramnagar on 22nd November 1848 during the Second Sikh War

Edwardes did not have sufficient strength for a siege, and the enterprise passed to Major General Whish with two brigades of infantry, a brigade of cavalry and a siege train.

Until this force captured Multan and re-joined him, Gough was forced to delay taking the offensive against the Sikhs, with his newly named “Army of the Punjab”.

At this stage in the Second Sikh War, it was far from clear who would be fighting against the British.

A Sikh general, Shere Singh, revolted against the Punjab government and marched with his army up the Chenab River towards the north of the province. Gough feared that Shere Singh would join his father, Chattar Singh, in the area of Peshawar. The rebels also held the capital of the Punjab, Lahore.

Shere Singh halted with his troops at Ramnagar, on the northern bank of the Chenab, and pushed outposts and guns across the river.

While the plain itself was good cavalry country, at this time of year the wide Chenab River shrank to a thin winding stream in a wide sandy bed, treacherous for horses and guns. The troops needed to ensure that they kept out of the river bed.

Gough decided to attack the Sikh troops on the southern side of the river, and, on 21st November 1848, sent forward Major General Campbell with a brigade of infantry and Brigadier General Cureton with the cavalry division.

In the early hours of 22nd November 1848, Gough joined Campbell’s division and ordered an attack on the Sikhs who were hurrying to cross back over the Chenab. Two batteries of horse artillery, accompanied by cavalry, advanced to the edge of the river and opened fire on the retreating Sikhs.

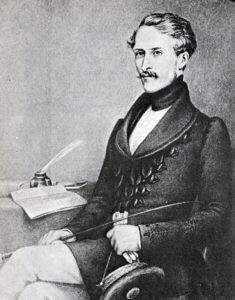

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Havelock, commanding 14th King’s Light Dragoons at the Battle of Ramnagar on 22nd November 1848 during the Second Sikh War

A force of mounted Sikh Gorcharras crossed from the north bank to protect their infantry comrades. As the Gorcharras advanced onto the plain, they were charged by Brigadier White with the 3rd King’s Own Light Dragoons, who drove the Sikhs back into the river bed, where White sensibly declined to follow.

One of the guns of the Bengal horse artillery, following in support, stuck in the quicksands of the river bed. The gunners were unable to extract the gun and it had to be abandoned.

Their success in forcing the Bengal horse artillery to abandon a gun caused the Sikhs to push more cavalry across the river. This time against Gough’s right flank.

General Gough ordered the 14th Light Dragoons to drive this new force back across the river. The colonel of the 14th, William Havelock, led his regiment and the 5th Bengal Light Cavalry in a headlong charge at the Sikhs, and, without stopping at the edge of the bank, led his men into the river.

It was apparent to the divisional commander, General Cureton, that Havelock was taking his two regiments into considerable danger. Cureton led a party of the 5th Bengal Light Cavalry in an attempt to halt the 14th in its charge, but was shot dead as he rode forward.

Havelock was killed in the melee in the river, while 12 other officers and 84 men of the two cavalry regiments became casualties before the 14th turned back and the battle ended.

The Sikhs had been cleared from the south bank of the River Chenab.

Casualties at the Battle of Ramnagar: British and Bengali casualties were around 150. Sikh casualties are estimated at a few hundred.

The body of Lieutenant Colonel Havelock, who had led the 14th King’s Light Dragoons into the charge, was found in the river bed twelve days after the action. The head had been cut off and the left arm and leg nearly severed. He lay with nine dead troopers of his regiment.

Piquet of the 14th King’s Light Dragoons in 1842: Battle of Ramnagar on 22nd November 1848 during the Second Sikh War

Follow-up to the Battle of Ramnagar: Gough decided to hold the Sikh force at Ramnagar, while General Sir Joseph Thackwell, who had taken over command of the Cavalry Division on the death of General Cureton, marched upstream and crossed to the north bank.

Thackwell, with a force of cavalry, infantry and guns marched up the Chenab, and crossed to the north side. To Gough’s chagrin no full action materialised, but the Army of the Punjab had forced the River Chenab.

Brigadier Cureton, killed at the Battle of Ramnagar on 22nd November 1848 during the Second Sikh War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Ramnagar:

- The death of Brigadier General Cureton, a cavalry commander of great experience and ability, was considered a grave loss to the British Army. Cureton fought through the Peninsular War in the ranks of the 14th Light Dragoons, the most consistently successful British cavalry regiment in that campaign, rising to the rank of sergeant. In 1813, Cureton was given a commission in an infantry regiment, before exchanging into the 16th Lancers in India. Of his three sons, one was severely wounded at Moodkee serving in the 3rd Light Dragoons, another was killed at Chillianwallah, while the third was at Aliwal as his father’s aide de camp and went on to raise his own Bengal Army cavalry regiment, Cureton’s Multanis. Cureton took air cushions on campaign with him as the most comfortable form of bedding. See the note to the Battle of Aliwal for Sir Harry Smith’s assessment of Cureton’s performance at that battle.

- Colonel William Havelock, who led the 14th Light Dragoons into the river at the Battle of Ramnagar and lost his life in the charge, also made his name in the Peninsular, acquiring from the Spanish troops that he led the nickname of “el chico blanco” or the blonde boy. It was said of him by his brother, the Henry Havelock of Indian Mutiny fame, “it was natural that an old Peninsular officer, who had not seen a shot fired in anger since Waterloo, should desire to blood the noses of his young dragoons.”

- At the beginning of the battle, the 14th Light Dragoons were dismounted, gathering turnips in a field. When the trumpets sounded to mount, a Sergeant Clifton quickly put a turnip inside his shako. In the charge, Clifton’s shako was cut to pieces by Sikh sword cuts. The turnip prevented Clifton from receiving any injury to his head, although he was cut about the shoulders. The turnip was sliced up.

- General Gough presented a sum of 5,000 rupees to the 5th Bengal Light Cavalry for their conduct in the battle. The 5th spent the sum in entertaining the 14th Light Dragoons to a feast. As their religion prevented them from eating with non-Hindus the soldiers of the 5th waited on the British troopers of the 14th.

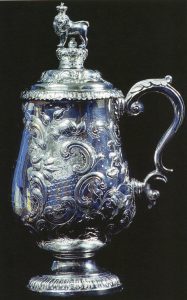

- The 5th Bengal Light Cavalry presented a silver tankard to the 14th King’s Light Dragoons to commemorate the battle. The tankard, entitled the ‘Ramnuggur Cup‘ is engraved with the battle honours of the 14th.

- “Ramnuggur Day” has been celebrated by the 14th Light Dragoons and its successor regiments on the anniversary of the battle, and is still commemorated by the King’s Royal Hussars.

Medals and decorations:

British and Indian soldiers who took part in the Second Sikh War received the silver medal entitled “Punjab Campaign, 1848-9”.

Clasps were issued for the battles (or in the case of Mooltan the siege) which were described as: “Mooltan”, “Chillianwallah”, and “Goojerat”. There was no clasp for Ramnagar.

Description of the medal:

Obverse. -Crowned head of Queen Victoria. Legend: “Victoria Regina.”

Reverse. -The Sikh army laying down its arms before Sir W.R. Gilbert and his troops near Rawal Pindi. Inscription “To the Army of the Punjab.” In exergue “MDCCCXLIX.”

Mounting. -Silver scroll bar and swivel.

Ribbon. -Dark blue with two thin yellow stripes, 1 ¼ inch wide.

References for the Battle of Ramnagar:

History of the British Army by Fortescue.

History of British Cavalry by the Marquis of Anglesey.

The previous battle, from the First Sikh War, is the Battle of Sobraon

The next battle of the Second Sikh War is the Battle of Chillianwallah