The battle fought in and to the north of the City of St Albans, on 17th February 1461 in the Wars of the Roses

The previous battle of the Wars of the Roses is the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross

The next battle of the Wars of the Roses is the Battle of Towton

War: Wars of the Roses

Date of the Second Battle of St Albans: 17th February 1461

Place of the Second Battle of St Albans: In and to the north of the City of St Albans in Hertfordshire in England.

Combatants at the Second Battle of St Albans: Lancastrians against the Yorkists

Queen Margaret of Anjou: Second Battle of St Albans, fought on 17th February 1461 in the Wars of the Roses

Commanders at the Second Battle of St Albans: Queen Margaret of Anjou nominally commanded the Lancastrian army assisted by Sir Andrew Trollope. Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, was the commander.

The principal Yorkist commanders were; Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, known as ‘Warwick the Kingmaker’, his brother, Lord Montagu and the Duke of Norfolk.

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, known as ‘Warwick the Kingmaker’: Second Battle of St Albans, fought on 17th February 1461 in the Wars of the Roses

Size of the armies at the Second Battle of St Albans: The Lancastrian army probably comprised some 10-12,000 men. The Yorkist army probably comprised some 8-10,000 men.

Winner of the Second Battle of St Albans: The Lancastrians under Queen Margaret defeated the Yorkist army, re-capturing King Henry VI.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Second Battle of St Albans: The senior commanders and their noble supporters and knights rode to battle on horseback, in armour, with sword, lance and shield.

Their immediate entourage comprised mounted men-at-arms, in armour and armed with sword, lance and shield, although often fighting on foot.

Both armies comprised strong forces of longbowmen.

Handheld Firearms were beginning to appear in numbers on the battlefield, but were still unreliable and dangerous to discharge.

Artillery, although widely used in warfare, was heavy, cumbersome and difficult to move and fire.

The end of the Hundred Years War caused numbers of English and Welsh men-at-arms and archers to return to their home countries from France. The wealthier English and Welsh nobles were able to recruit companies of disciplined armed retainers from these veterans, which formed the backbone of their field armies.

The Lancastrian army of Queen Margaret of Anjou, during its march from the North of England, attracted numbers of Border Reivers and other bandit elements, intent on pillaging the countryside and towns and having little intention of fighting for the Lancastrian cause.

It is said that Warwick failed to take advantage of his time in London to raise troops to face the Lancastrian advance from the north.

However, Warwick did equip his army with a wide range of implements of war; guns, both cannon and hand-held and petards or early hand-grenades, brought by a contingent of Burgundian mercenaries from Europe; caltrops or multi-pointed metal obstacles, thick nets interlaced with metal spikes to block the enemy’s advance and portable shields for the protection of archers and crossbowmen. All these instruments were deployed at the Second Battle of St Albans, unfortunately facing in the wrong direction.

Background to the Second Battle of St Albans: At the Battle of Northampton on 10th July 1460, a disastrous defeat for the Lancastrian cause, King Henry VI fell into the hands of the Yorkists, who escorted him back to London.

For the time being, the King was a puppet in the hands of the Yorkist nobles and was compelled to endorse their decisions in government.

Queen Margaret escaped to Wales with the young Prince Edward, while the Lancastrian nobles in the north raised a new army.

In early December 1460, the Duke of York marched north to meet the Lancastrians.

The two sides met in battle at Wakefield on 30th December 1460. The Yorkists were heavily defeated. The Duke of York was killed in the battle and his seventeen-year-old son, the Duke of Rutland, was recognized and killed by Lord Clifford in Wakefield after the battle. The Earl of Salisbury was captured and executed.

The heads of the three senior Yorkist nobles, York, Rutland and Salisbury, were displayed on stakes in the City of York, a matter of some irony for the Lancastrians.

Queen Margaret, now in Scotland seeking assistance from the Regent, Mary of Goulder, mother of the child King James III, left to join the Lancastrian army in York and begin a march on London.

As the Lancastrian army advanced south, swollen with northern freebooters, it sacked the towns of Grantham, Stamford, Peterborough, Huntingdon and Royston.

The south of England was terrorised by the advancing Lancastrian freebooters.

The main Yorkist army, commanded by the Earl of Warwick, with his younger brother, John Neville, Lord Montagu and the Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk was in London.

A second Yorkist army, commanded by the Earl of March (later King Edward IV), lay at Ludlow on the Welsh border.

Hard on the heels of the news of the Yorkist defeat at Wakefield, the Earl of March heard that a Lancastrian army had landed in South-West Wales.

March advanced to meet the Lancastrians and soundly beat them at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross on 2nd February 1461.

On 12th February 1461, taking King Henry VI with him, Warwick marched north to St Albans from London to intercept Queen Margaret’s Lancastrian army.

London to St Albans is a distance of around 19 miles. It is said that the Yorkist army arrived at St Albans in the evening of the same day.

Over the next three days, the Yorkists prepared to give battle to Queen Margaret’s Lancastrian army at St Albans.

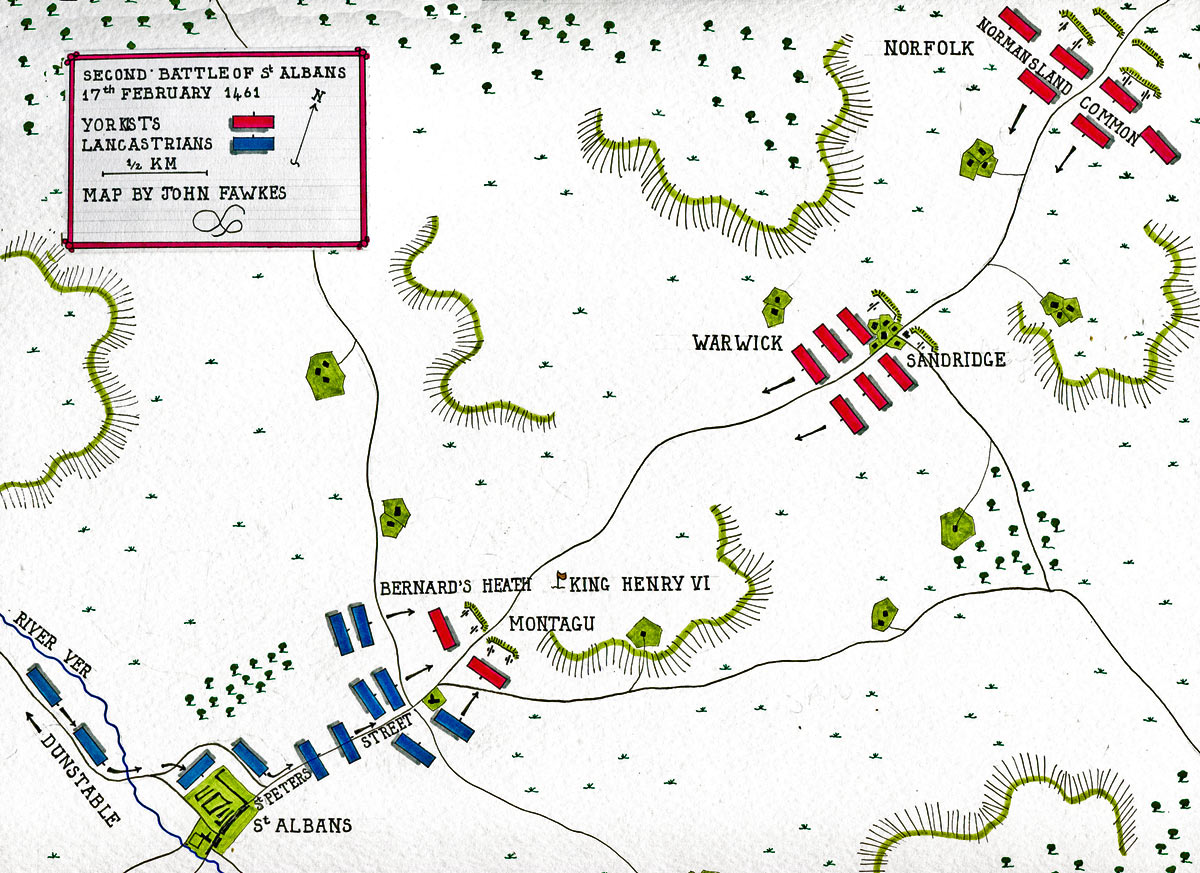

For the Lancastrian army, the direct route to London was down the London Road from Royston to Hitchin, join the road towards St Albans at Wheathamstead and, crossing Normansland Common and Bernard’s Heath, via the hamlet of Sandridge, into St Albans down the northern St Peter’s Street.

South of St Albans, the route to London followed the old Roman Watling Street.

Warwick appears to have made the assumption that the Lancastrians would take this route and prepared the Yorkist positions on this basis.

A strong contingent of Yorkist longbowmen was stationed in the centre of St Albans, around the Market Place.

Lord Montagu occupied the ground at Bernard’s Heath, on the road leading north out of St Albans. Warwick’s men occupied Sandridge and the Duke of Norfolk was furthest to the north, at Normansland Common.

It is reported that the Yorkist army spent the three days, from 12th to 16th February 1461, preparing fortified defences, using the various apparatus and setting up the guns of the Burgundian mercenaries.

The focus of the Yorkist defences was northwards up the road towards Hitchin, the expected line of the Lancastrian approach.

Meanwhile, the Lancastrians were diverted from their expected route by news of a Yorkist rising in Dunstable, led by a local butcher and assisted by a small contingent of Yorkist troops, led by Sir Robert Poynings, one of the Duke of Norfolk’s men.

Instead of continuing south from Hitchin, Queen Margaret’s Lancastrian army turned west and made for Dunstable, where the butcher’s rising was suppressed with considerable violence and the town sacked.

It is said that the butcher killed himself in remorse at the devastation he had brought on his town.

The Lancastrians continued on their way towards St Albans, but now on Watling Street, approaching St Albans from the west and bypassing the Yorkist army deployed on the road to the north of St Albans.

———————————-

Map of the Second Battle of St Albans, fought on 17th February 1461 in the Wars of the Roses: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Second Battle of St Albans: The Yorkists deployed scouts or ‘prickers’ in advance of their positions to warn of the Lancastrian approach.

One of these scouts came in to report that Queen Margaret’s army was nine miles away on the Dunstable road.

Criticism is levelled at Warwick and the Yorkist command that nothing, or too little, was done, in the light of this information, to re-orientate the Yorkist army to face the Lancastrian advance.

The Lancastrians did not halt at Dunstable. After destroying the small Yorkist rising led by the butcher, Queen Margaret’s army marched through the night down Watling Street, reaching St Albans earlier than Warwick was likely to have expected.

Large medieval armies were made up of different elements, under diverse leadership and did not readily comply with sudden and unexpected changes in orders.

After spending several days establishing defensive positions facing north on the northern road, it would have been far from easy for the Yorkists to move to new positions, facing in a different direction, at such short notice.

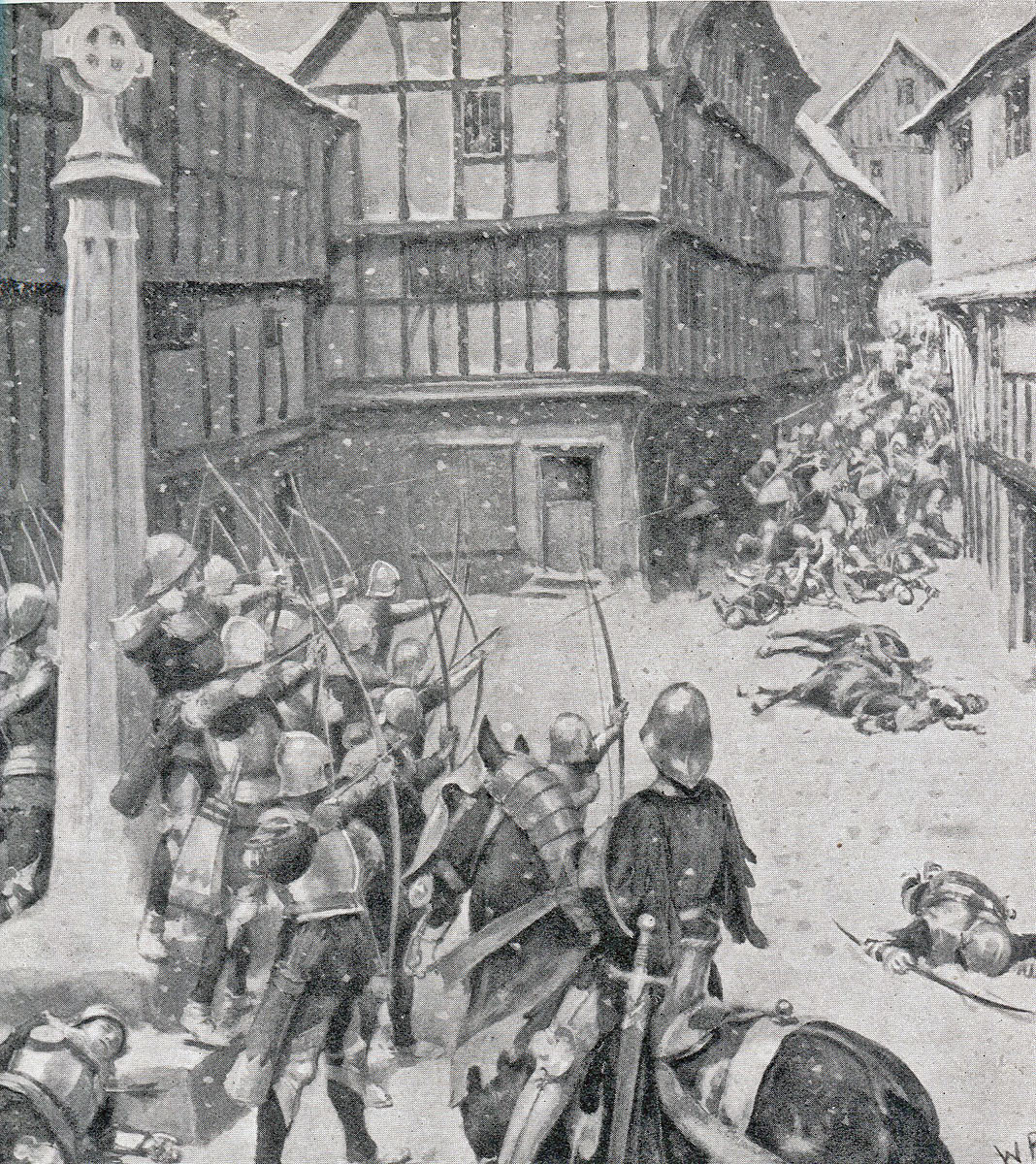

At dawn on 17th February 1461, the Lancastrian vanguard, led by Sir Andrew Trollope and containing a force of 5,000 experienced and disciplined men, marched into St Albans from the west and the south and began the attack on the Yorkist rearguard, established in the city.

Heavy fighting started as the Lancastrians encountered the Yorkist archers in the area of the Market Place in the centre of St Albans, particularly around the clock tower.

Yorkist archers fire on the attacking Lancastrians at the Second Battle of St Albans, fought on 17th February 1461 in the Wars of the Roses

Lancastrian mounted troops, commanded by the Earl of Somerset, entered the north-west of the city and advanced into St Peter’s Street. The Lancastrians turned north and began the attack on Lord Montagu’s men outside the city, at Bernard’s Heath.

Montagu’s entrenchments were built, over the previous days, to face an enemy advancing from the north. He was now being attacked in the rear and was forced to extemporise a defence in that direction.

The cumbersome guns required to be turned around, a difficult and time-consuming exercise, not easily done in the face of a fast-moving and unexpected assault.

A fierce fight developed between Montagu’s men and the advancing Lancastrians.

While little support appears to have come up for Montagu from the rest of the Yorkist army, positioned along the northern road, a stream of Lancastrian troops continued to arrive from Dunstable and joined the attack on Montagu.

Eventually, heavily outnumbered and with little support from the rest of the army, Montagu’s force disintegrated and fled, Lord Montagu and Lord Berners being captured.

Clock Tower in the centre of the city: Second Battle of St Albans, fought on 17th February 1461 in the Wars of the Roses

King Henry VI was accompanying the Yorkist army, nominally as their leader, but, in practice, under duress. The King’s tent was pitched on Bernard’s Heath with Lord Montagu’s force, as the Yorkist leadership expected this to be in the rear of any battle and therefore a safe place to preserve the King from injury and to ensure that he remained with the Yorkist army.

During the course of the defeat of Lord Montagu’s men, a Yorkist knight, Thomas Hoo, suggested to the King that he join the Lancastrian army, as the Yorkist army was disintegrating around him.

King Henry VI took up this proposal and sent a message to the Earl of Northumberland, saying that he proposed to join his Queen’s army.

A number of Lancastrian noblemen collected the King from his tent and took him into their lines, taking care to display the Royal Standard in the Lancastrian lines.

In addition to being routed by the Lancastrian troops, the Yorkists saw that they were now no longer fighting for the King, but against him and might well be classed as traitors. The disintegration of Montagu’s force was further accelerated.

At the northern end of the Yorkist positions, Warwick was completely surprised by the Lancastrian attack in his rear.

It took a considerable time for Warwick to persuade his men to march back and support Lord Montague. At this point a Kentish squire in the Yorkist army, named Lovelace, changed sides, causing additional confusion and dismay in the Yorkist ranks.

The rout enveloped the rest of the Yorkist army, which began to break up in flight.

Warwick rallied his men and conducted a fighting withdrawal up the road through Sandridge and halted on the high ground before the Normansland Common.

Warwick was not further attacked by the pursuing Lancastrians, who were by now widely dispersed across the battlefield.

As night fell, the Earl of Warwick marched away, with around 4,000 men, probably less than half the army with which he had started the battle. In addition to his casualties, Warwick had also lost the King, the essential tool for Warwick to rule the realm.

Elizabeth Woodville, future queen of King Edward IV: Second Battle of St Albans, fought on 17th February 1461 in the Wars of the Roses

Casualties at the Second Battle of St Albans: The casualties were probably some 500 Lancastrian dead and wounded and around 2,000 Yorkist dead and wounded.

The only prominent Lancastrian killed was Sir John Grey of Groby, father of Elizabeth Woodville, later Queen to King Edward IV.

Lord Montagu and Lord Berners were made prisoner by the Lancastrians.

Follow-up to the Second Battle of St Albans: After the battle, King Henry VI was re-united with his wife, Queen Margaret. At her suggestion the King knighted the Prince of Wales, Prince Edward. He also knighted some thirty Lancastrians.

The Earl of Warwick, with the remains of the Yorkist army, marched west to join the Earl of March in Ludlow.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Second Battle of St Albans:

- Included among the Lancastrians knighted by King Henry VI after the battle, was Sir Andrew Trollope, who led the initial attack on the Yorkist archers in St Albans. Trollope stated that he was wounded in the foot by a caltrop. He went on to say ‘My Lord, I have not deserved this (the knighthood) for I slew no more than fifteen men… I stood still in one place and they came to me… but they stayed with me..’

- The Yorkists placed King Henry VI in the care of Lord Bonville and Sir Thomas Kyriell for the battle. Once the battle was lost, Bonville and Kyriell escorted the King to Lord Clifford’s tent, where he was joined by Queen Margaret. The Queen asked the Prince of Wales how Bonville and Kyriell should die and the Prince replied that they should be executed, which they duly were.

References for the Second Battle of St Albans:

The Battles of St Albans by Peter Burley, Michael Elliott and Harvey Watson

The Wars of the Roses by Michael Hicks

The Chronicles of the Wars of the Roses

British Battles by Grant

The previous battle of the Wars of the Roses is the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross

The next battle of the Wars of the Roses is the Battle of Towton