Battle of Kandahar, also known as the Battle of Baba Wali, fought on 1st September 1880 and the last battle of the Second Afghan War; General Roberts’ crowning success after his march from Kabul

General Roberts’ army on the march from Kabul to Kandahar: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Henri Dupray

The previous battle of the Second Afghan War is the Battle of Maiwand

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Isandlwana

To the Second Afghan War index

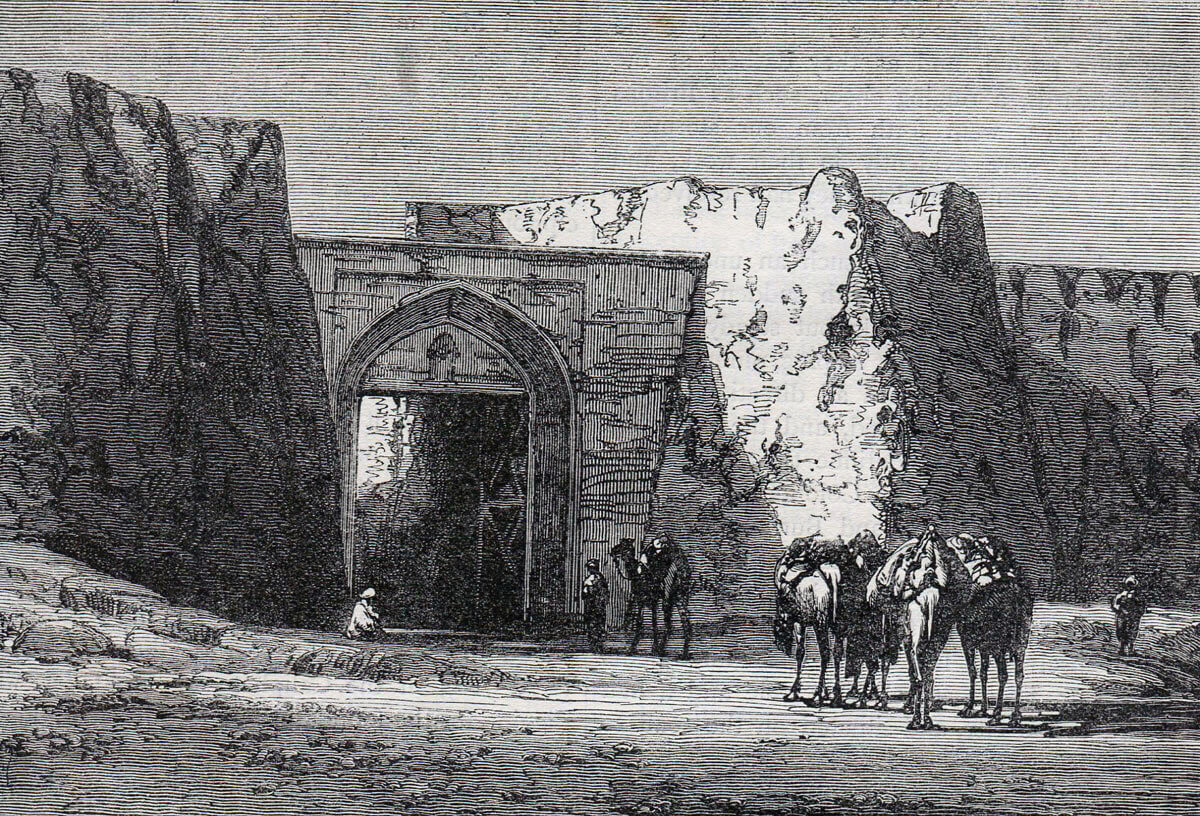

Baba Wali in the Argandhab Valley: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

Battle: Battle of Kandahar or the Battle of Baba Wali.

War: Second Afghan War

Date of the Battle of Kandahar: 1st September 1880.

Place of the Battle of Kandahar: Southern Afghanistan.

Combatants at the Battle of Kandahar: Troops of the British, Bengal and Bombay Armies against Afghan regular troops and tribesmen.

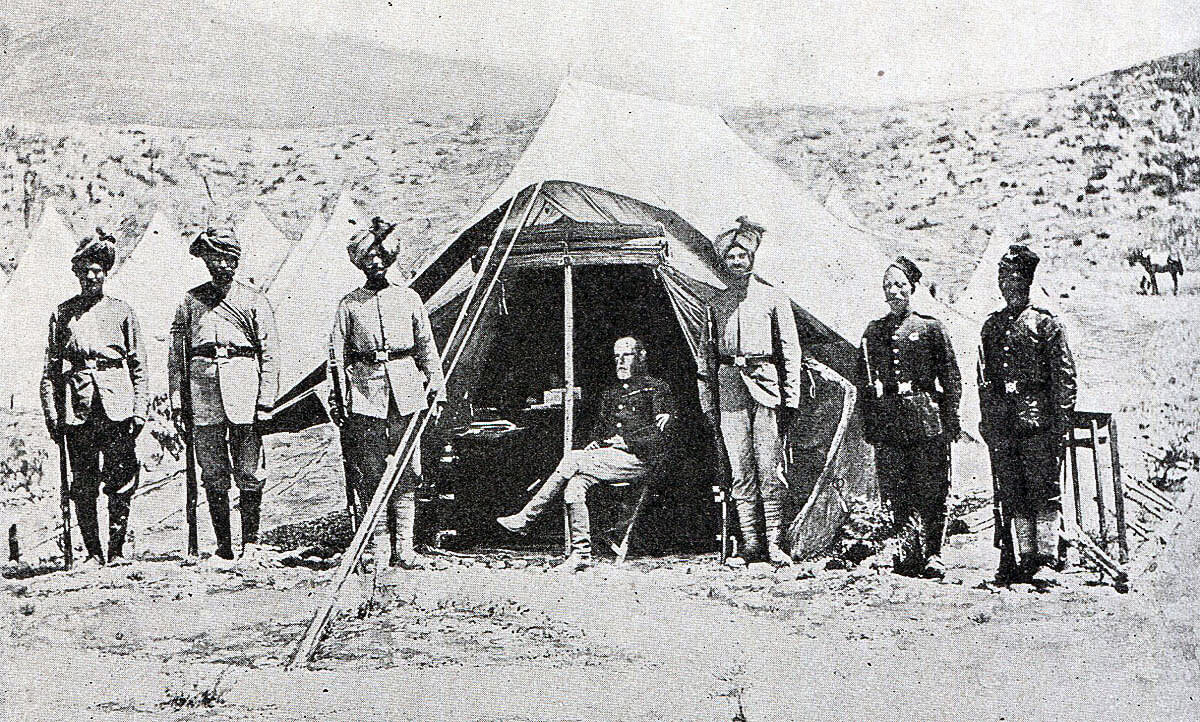

Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Roberts VC with his Pathan, Sikh and Gurkha orderlies: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

Generals at the Battle of Kandahar: Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Roberts VC KCB against Ayub Khan.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Kandahar: General Roberts force from Kabul comprised 2,562 British and 7,151 Indian troops. Some 2,000 troops also took part in the final battle from the British and Indian troops of the Kandahar garrison. The Afghan army comprised 3,000 cavalry and 12,000 infantry and tribesmen with 6 batteries of artillery (36 guns) and the two RHA guns captured at the Battle of Maiwand.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Kandahar:

The British and Indian forces were made up, predominantly, of native Indian regiments from the armies of the three British presidencies, Bengal, Bombay and Madras, with smaller regional forces, such as the Hyderabad contingent, and the newest, the powerful Punjab Frontier Force.

The Mutiny of 1857 brought great change to the Indian Army. Prior to the Mutiny, the old regiments of the presidencies were recruited from the higher caste Brahmins, Hindus and Muslims of the provinces of central and eastern India, principally Oudh. Sixty of the ninety infantry regiments of the Bengal Army mutinied in 1857 and many more were disbanded, leaving few to survive in their pre-1857 form. A similar proportion of Bengal Cavalry regiments disappeared.

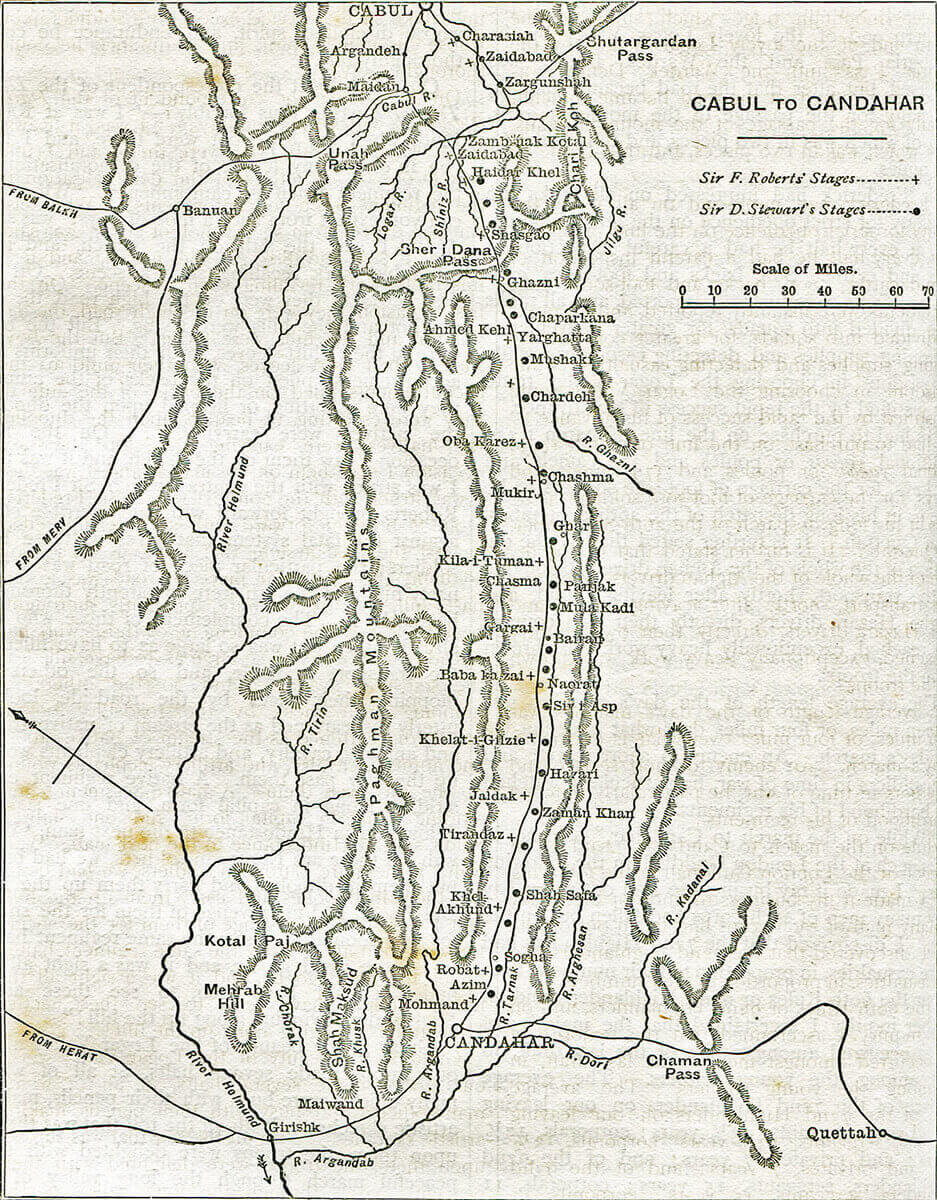

Map showing the routes of General Stewart and General Roberts between Kabul and Kandahar in the Second Afghan War

The British Army overcame the mutineers with the assistance of the few loyal regiments of the Bengal Army and the regiments of the Bombay and Madras Presidencies, which on the whole did not mutiny. But principally, the British turned to the Gurkhas, Sikhs, Muslims of the Punjab and Baluchistan and the Pathans of the North-West Frontier for the new regiments with which Delhi was recaptured and the Mutiny suppressed.

After the Mutiny, the British developed the concept of ‘the Martial Races of India’. Certain Indian races were more suitable to serve as soldiers, went the argument, and those were, coincidentally, the races that had saved India for Britain. The Indian regiments that invaded Afghanistan in 1878, although mostly from the Bengal Army, were predominantly recruited from the martial races; Jats, Sikhs, Muslim and Hindu Punjabis, Pathans, Baluchis and Gurkhas.

Robert’s army on the march from Kabul to Kandahar: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Orlando Norie

Prior to the Mutiny, each Presidency army had a full quota of field and horse artillery batteries. The only Indian artillery units allowed to exist after the Mutiny were the mountain batteries. All the horse, field and siege batteries were, from 1859, found by the British Royal Artillery.

In 1878, the regiments were beginning to adopt khaki for field operations. The technique for dying uniforms varied widely, producing a range of shades of khaki, from bottle green to a light brown drab.

As regulation uniforms were unsatisfactory for field conditions in Afghanistan, the officers in most regiments improvised more serviceable forms of clothing.

Every Indian regiment was commanded by British officers, in a proportion of some 7 officers to 650 soldiers, in the infantry. This was an insufficient number for units in which all tactical decisions of significance were taken by the British and was particularly inadequate for less experienced units.

The British infantry carried the single shot, breech loading, .45 Martini-Henry rifle. The Indian regiments still used the Snider; also a breech loading single shot rifle, but of older pattern and a conversion of the obsolete muzzle loading Enfield weapon.

The cavalry was armed with sword, lance and carbine, Martini-Henry for the British troopers, Snider for the Indian sowars.

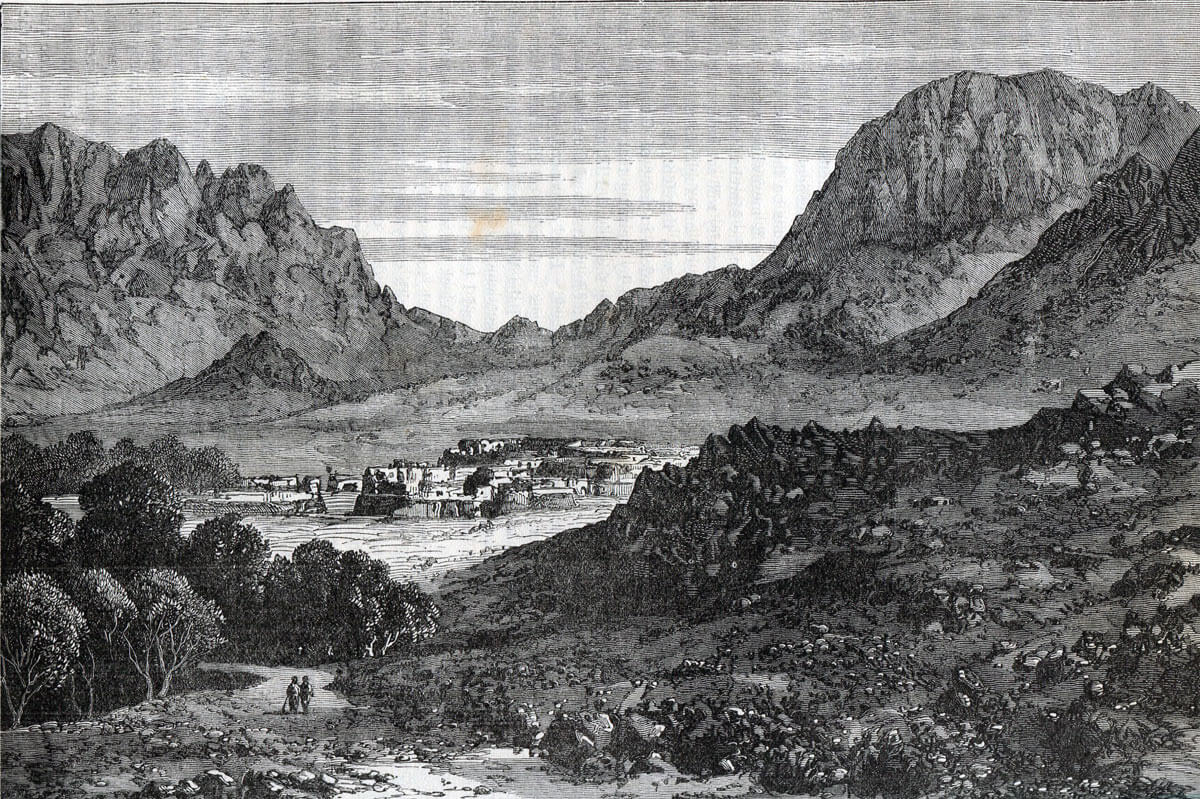

First view of Kandahar for the invading British and Indian Army: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

The British artillery, using a variety of guns, many smooth bored muzzle loaders, was not as effective as it could have been, if the authorities had equipped it with the breech loading steel guns being produced for European armies. Artillery support was frequently ineffective and on occasions the Afghan artillery proved to be better equipped than the British.

General Roberts’ army on the march from Kabul to Kandahar: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

The army in India possessed no higher formations above the regiment in times of peace, other than the staffs of static garrisons. There was no operational training for staff officers. On the outbreak of war, brigade and divisional staffs had to be formed and learn by experience.

The British Army, in 1870, replaced long service with short service for its soldiers. The system was not yet universally applied, so that some regiments in Afghanistan were short service and others still manned by long service soldiers. The Indian regiments were all manned by long service soldiers. The universal view seems to have been that the short service regiments were weaker both in fighting effectiveness and disease resistance than the long service.

Central India Horse: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by A.C. Lovett

Winner of the Battle of Kandahar: The British and Indian Army.

British Regiments at the Battle of Kandahar:

Regiments from Kabul:

9th Lancers, from 1966 9th/12th Royal Lancers *

3rd Bengal Cavalry *

23rd Bengal Cavalry *

1st Central India Horse *

2nd Central India Horse *

three batteries of Mountain Artillery.

2nd Battalion 60th Rifles, now the Rifles. *

72nd Highlanders, later Seaforth Highlanders, now the Royal Regiment of Scotland. *

92nd Highlanders, later Gordon Highlanders, now the Royal Regiment of Scotland. *

15th Bengal Native Infantry (Ludhiana Sikhs) *

23rd Bengal Native Infantry (Punjab Pioneers) *

24th Bengal Native Infantry (Punjabis) *

25th Bengal Native Infantry (Punjabis) *

2nd Prince of Wales’s Own Gurkhas *

4th Gurkhas *

5th Gurkhas *

2nd Sikh Infantry *

3rd Sikh Infantry *

Kandahar Regiments:

E/B Battery Royal Horse Artillery

3rd Queen’s Own Cavalry (Bombay Army) *

3rd Scinde Horse (Bombay Army) *

HM 7th Royal Fusiliers, now the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. *

HM 66th Regiment (remainder of), from 1882 the Royal Berkshire Regiment and now the Rifles. *

1st Grenadiers (Bombay Army) *

4th Bombay Native Infantry *

19th Bombay Native Infantry *

28th Bombay Native Infantry (Jacob’s Rifles) *

29th Balluch Battalion *

* These regiments have Kandahar as a battle honour.

The Order of Battle of the Kabul-Kandahar Field Force:

Commander in Chief: Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Roberts VC. KCB.

Cavalry Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Hugh Gough VC CB.

9th Lancers

3rd Bengal Cavalry

23rd Bengal Cavalry

Central India Horse

Artillery Brigade: commanded by Colonel Alured Johnson

three batteries of Mountain Artillery.

Infantry Division: commanded by Major General Sir John Ross KCB

First Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General H. Macpherson VC CB

92nd (Gordon) Highlanders

23rd Bengal Native Infantry (Punjab Pioneers)

24th Bengal Native Infantry (Punjabis)

2nd Prince of Wales’s Own Gurkhas

Hauling a gun out of a ravine on the March from Kabul to Kandahar: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Second Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General TD Baker CB

72nd (Duke of Albany’s) Highlanders

2nd Sikh Infantry

3rd Sikh Infantry

5th Gurkhas

Third Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General CM MacGregor CB

2nd Battalion 60th Rifles

15th Bengal Native Infantry (Ludhiana Sikhs)

25th Bengal Native Infantry (Punjabis)

4th Gurkhas

Account of the Battle of Kandahar:

The disastrous defeat at the Battle of Maiwand, forty miles west of Kandahar, on 27th July 1880, threw British plans into disarray, after two years of uninterrupted success in the Second Afghan War. The remaining Bombay brigade found itself besieged in Kandahar by Ayub Khan’s victorious army, the nearest support hundreds of miles away in Kabul and in Quetta, forces commanded by General Roberts and Brigadier General Phayre respectively.

Roberts moved first, his troops being relatively concentrated around the Afghan capital, while Phayre’s Bombay troops were scattered along the lengthy lines of communication connecting Kandahar with India, from Quetta to the Indus River.

On 8th August 1880, Roberts marched out of the Sherpur Cantonment in Kabul with his Kabul-Kandahar Field Force; his renowned march to Kandahar had begun.

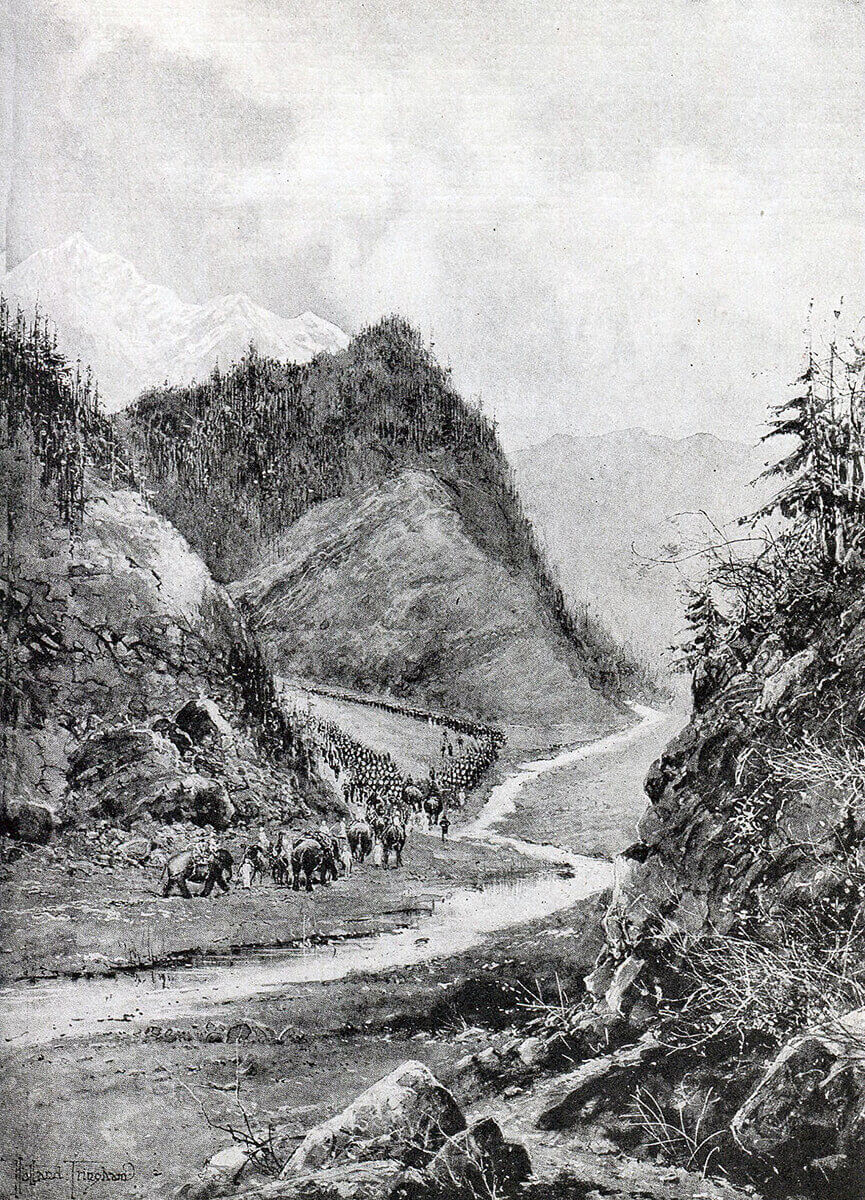

The Central Indian Horse and a battery of artillery, coming up from Gandamak, caught up the next day as Robert’s army moved across high ground to join the main Kandahar road near Ghuznee, before marching south down that road. The pace was forced as hard as possible; only mountain artillery accompanying the infantry and cavalry; with supplies carried by camel. The days were hot and the nights cold; the troops marching out in the early morning to avoid the full heat of the sun, halting a few minutes every hour, with camp pitched at around midday. With this routine, Roberts’ troops managed to cover up to twenty miles a day.

General Roberts’ army on the march from Kabul to Kandahar: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Joseph Holland Tringham

On 23rd August 1880, the force reached Kelat-i-Ghilzai, one hundred and forty miles beyond Ghuznee. The pace of the march was taking its toll, with soldiers falling sick at the rate of five hundred a day.

Messages from Kandahar informed Roberts that there was no pressing urgency, as the garrison was well able to hold out for some time yet and so, with eighty-eight miles to go, Roberts’ permitted his force to rest at Kelat-i-Ghilzai. When he moved on, Roberts took the British garrison with him, it no longer being part of the British plan to hold the town.

92nd Highlanders attacking Gaudi-Mullah-Sahibdad during the Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

On 27th August 1880, word reached Roberts that Ayub Khan had abandoned his siege of Kandahar and withdrawn westwards. Roberts sent Brigadier General Gough’s cavalry brigade to search him out.

Roberts halted at Robat on 28th August 1880, to allow his force to concentrate. Officers came out from Kandahar to give him the latest intelligence and consult with him.

72nd Highlanders and 92nd Highlanders at the Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Richard Simkin

On 31st August 1880, the Kabul Field Force reached Kandahar and entered the city. Roberts’ 10,000 troops had marched three hundred miles in three weeks.

Drummer Roddick defending his officer during the Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

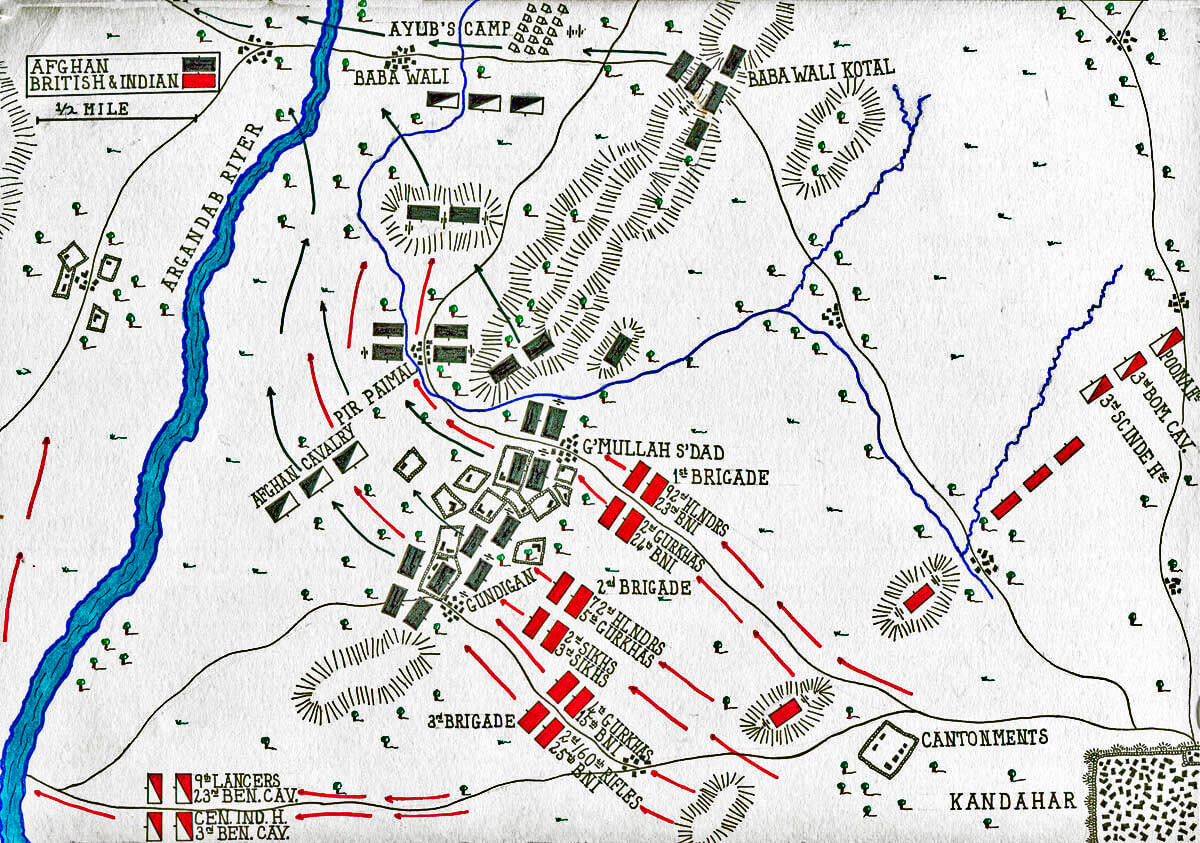

Roberts resolved to move against Ayub Khan the same day. Ayub’s camp lay to the west of Kandahar, between the Baba Wali range of hills, which rise to 5,000 feet and the Argandab River, the hills breached by the Baba Wali Kotal, a defile, and the Murcha Pass. The main assault would be made by the Kabul Field Force, with Bombay troops providing a diversion. Nuttall’s brigade of Bombay cavalry, survivors from the battle at Maiwand, was to picket the Murcha, while Bombay infantry and the 7th Royal Fusiliers threatened the Baba Wali Kotal. In the main attack, Robert’s Bengal force would move around the southern end of the hills and advance north up the river to Ayub’s camp, taking the villages on the way.

Roberts had 11,000 men and 32 guns in the field, against Ayub Khan’s 15,000 Afghan regular troops and tribesmen and 32 guns.

The battle began the next morning at around 9.30am with artillery bombardments of the Baba Wali Kotal and the foremost villages held by the Afghans.

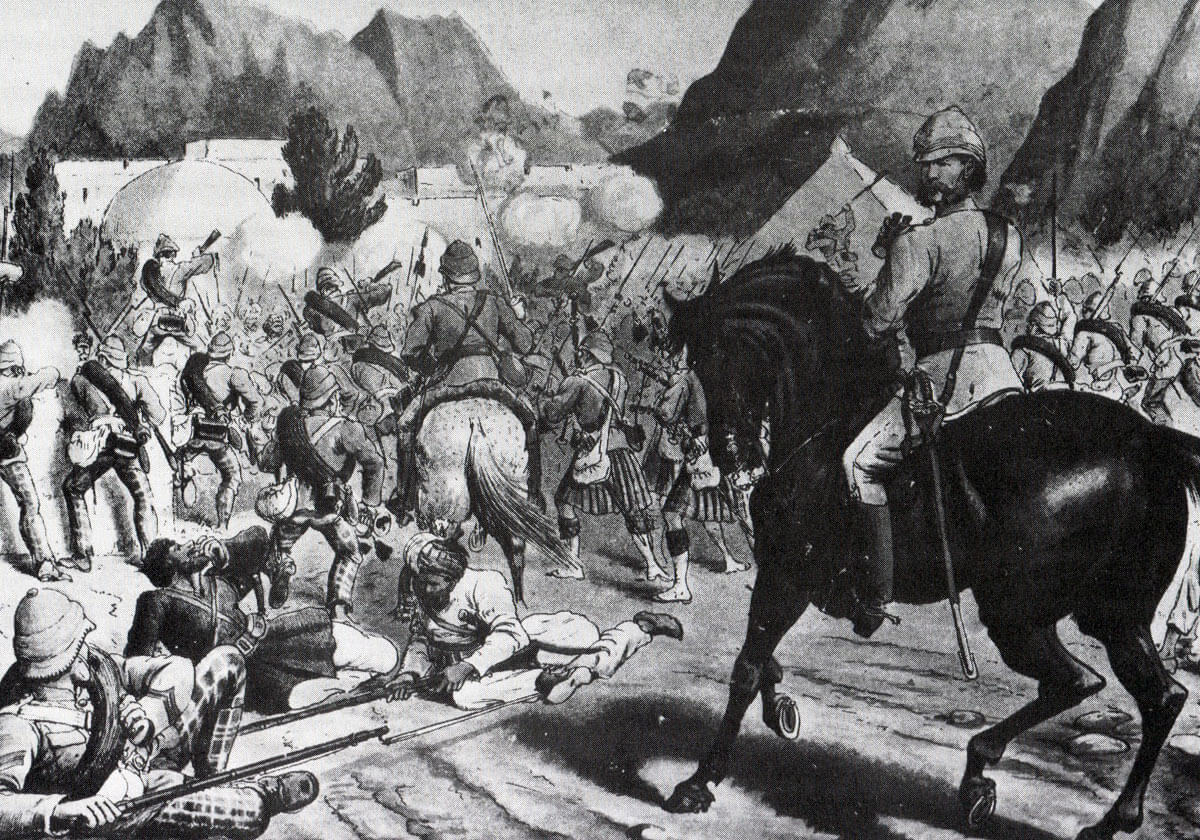

Following the bombardment, the 92nd Highlanders and the 2nd Gurkhas, supported by the 23rd and 24th BNI attacked the village of Gundimullah Sahibdad. After two hours of close combat the village was carried and the British and Indian troops moved on to the next fortified village, Pir Paimal.

To the south, the 72nd (Albany) Highlanders and the 2nd Sikhs took Gundigan, the colonel of the 72nd being killed in the assault.

2nd Gurkhas and Highlanders repelling an Afghan attack during the march to Kandahar: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

At around midday, both infantry brigades began the assault on Pir Paimal, the last stronghold shielding Ayub’s camp, the Third Brigade coming up in support.

As Roberts planned, the Afghans, their retreat threatened by the advance on Pir Paimal, began to melt away. The final Afghan fortifications, outside the camp, were heavily defended by guns, leading the British and Indian troops to expect a severe test. The regiments stormed forward, led by Major George White of the 92nd and Lieutenant Colonel Money of the 3rd Sikhs, to find the line abandoned. The Afghans had gone.

As the infantry advanced, Gough’s cavalry brigade picked its way through the maze of walled gardens and fields, only to be ordered back, to cross the Argandab River and cut off the Afghan retreat. By the time the cavalry had retraced their path and crossed the river, the horses were exhausted and the Afghans had largely gone, retreating west towards Herat.

The last battle of the Second Afghan War had been fought.

Casualties at the Battle of Kandahar:

Roberts’ force captured all Ayub Khan’s guns, including the two guns captured from the Royal Horse Artillery at the Battle of Maiwand. British and Indian casualties were 248 killed and wounded. Afghan casualties were estimated at around 2,500 killed, wounded and captured.

The commanding officer of the 72nd Highlanders, Lieutenant Colonel Brownlow, was killed.

Madras Sappers and Miners: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Richard Simkin

Follow-up to the Battle of Kandahar:

The British and Indian regiments finally withdrew from Afghanistan in April 1881. By the Treaty of Gandamak, signed the previous year, a substantial swathe of Afghan territory became part of India, including much mountainous tribal territory. The result was sixty-five years of almost incessant warfare between those tribes and the British and Indian Armies.

The Second Afghan War imposed an enormous financial strain on the Government of India, leading to the disbanding of several Indian Army regiments, as an economy measure.

92nd Highlanders attacking Gaudi-Mullah-Sahibdad during the Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

- Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Kandahar:

• Roberts’ march to Kandahar captured the imagination of the Victorian British Empire and was considered a triumph of determination and organisation. General Roberts was later elevated to the peerage as a baron, earl and then a viscount.

• General Roberts, an artillery officer known to his soldiers affectionately as ‘Bobs’, suffered the loss of an eye in childhood. An Old Etonian, Roberts won the Victoria Cross in the Indian Mutiny and went on to command the Indian Army and then the British and Empire troops in the Boer War. He suffered personal tragedy in the death of his son, Freddie dying in the attempt to rescue the guns at the Battle of Colenso in the Boer War, winning a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Lieutenant Menzies of the 92nd Highlanders defended by Drummer Roddick during the Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Skeoch Cumming

• During the assault on Gundimullah, Lieutenant Menzies of the 92nd was attacked by several Ghazis, or fanatical Afghan tribesmen. Knocked to the ground, Menzies was rescued first by a drummer from his own regiment and then by a Gurkha.

- Major George White earned the Victoria Cross leading the attack on the Afghan fortification. He was followed by Sepoy Inderbir Lama of the 2nd Gurkhas, who marked an Afghan gun as taken for his regiment by hanging his cap over the muzzle. White commanded the British force shut up in Ladysmith during the Boer War.

• During the confusion of the final attack on the Afghan camp, Lieutenant Hector Maclaine, Royal Horse Artillery, a prisoner from the retreat after the Battle of Maiwand, was murdered by his Afghan guards, with a sepoy prisoner.

• During the Second Afghan War, Colour Sergeant Hector MacDonald of the 92nd was commissioned in the field for bravery and initiative. MacDonald achieved promotion to brigadier and distinguished himself in the Egyptian campaign.

• A week after the battle, Brigadier General Daubeny and a force marched to Maiwand, to bury the British and Indian dead and examine the scene of the heavy defeat of the previous month.

British Officer wearing the Second Afghan War Medal and the Kabul and Kandahar Star: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

• British officers irreverently referred to Roberts’ march to Kandahar, apparently competing with Phayre to relieve the city, as ‘the Race for the Peerage’.

- A memorial to Lieutenant Colonel Brownlow and the casualties of the 72nd Highlanders in the Second Afghan War stands on the Edinburgh Castle Esplanade.

References for the Battle of Kandahar:

The Afghan Wars by Archibald Forbes

The Road to Kabul; the Second Afghan War 1878 to 1881 by Brian Robson.

Recent British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Second Afghan War is the Battle of Maiwand

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Isandlwana

To the Second Afghan War index