The spectacular and hard-fought battle around the Sherpur Cantonment outside Kabul, that led on 23rd December 1879 to the defeat of the Afghan tribesmen led by Mohammed Jan

British and Punjab cavalry attacking the Afghans in the Chardeh Valley at the Battle of Kabul in December 1879 during the Second Afghan War

The previous battle of the Second Afghan War is the Battle of Charasiab

The next battle of the Second Afghan War is the Battle of Ahmed Khel

To the Second Afghan War index

Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Roberts VC, British commander at the Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War

Battle: Kabul 1879

War: Second Afghan War.

Date of the Battle of Kabul 1879: 23rd December 1879

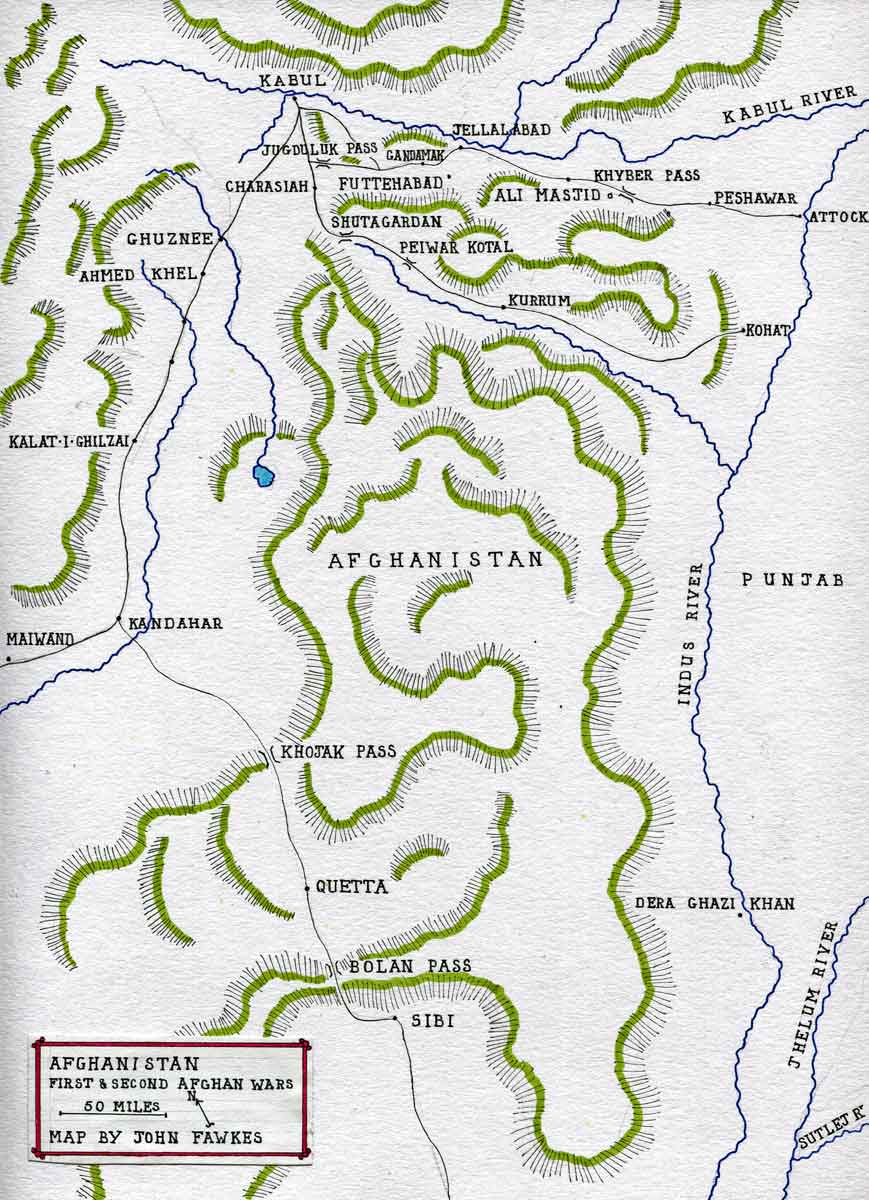

Place of the Battle of Kabul 1879: Kabul in Northern Afghanistan.

Combatants at the Battle of Kabul 1879: British and Indian troops against Afghan tribesmen.

Generals at the Battle of Kabul 1879: Major General Sir Frederick Roberts VC against Mohammed Jan.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Kabul 1879: 7,000 British and Indian troops against a varying number of Afghan tribesmen and regular soldiers, probably around 50,000 at the largest.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Kabul 1879:

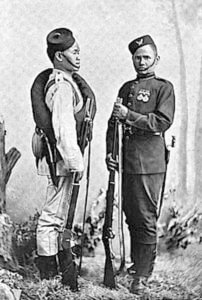

The British and Indian forces were made up, predominantly, of native Indian regiments from the armies of the three British presidencies, Bengal, Bombay and Madras, with smaller regional forces, such as the Hyderabad contingent, and the newest, the powerful Punjab Frontier Force.

The Mutiny of 1857 had brought great change to the Indian Army. Prior to the Mutiny, the old regiments of the presidencies were recruited from the higher caste Brahmins, Hindus and Muslims of the provinces of central and eastern India, principally Oudh. Sixty of the ninety infantry regiments of the Bengal Army mutinied in 1857 and many more were disbanded, leaving few to survive in their pre-1857 form. A similar proportion of Bengal Cavalry regiments disappeared.

The British Army overcame the mutineers with the assistance of the few loyal regiments of the Bengal Army and the regiments of the Bombay and Madras Presidencies, which on the whole did not mutiny. But principally, the British turned to the Gurkhas, Sikhs, Muslims of the Punjab and Baluchistan and the Pathans of the North-West Frontier for the new regiments with which Delhi was recaptured and the Mutiny suppressed.

After the Mutiny, the British developed the concept of ‘the Martial Races of India’. Certain Indian races were more suitable to serve as soldiers, went the argument, and those were, coincidentally, the races that had saved India for Britain. The Indian regiments that invaded Afghanistan in 1878, although mostly from the Bengal Army, were predominantly recruited from the martial races; Jats, Sikhs, Muslim and Hindu Punjabis, Pathans, Baluchis and Gurkhas.

Prior to the Mutiny, each Presidency army had a full quota of field and horse artillery batteries. The only Indian artillery units allowed to exist after the Mutiny were the mountain batteries. All the horse, field and siege batteries were, from 1859, found by the British Royal Artillery.

92nd Highlander in Afghanistan: Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Skeoch Cumming

In 1878, the regiments were beginning to adopt khaki for field operations. The technique for dying uniforms varied widely, producing a range of shades of khaki, from bottle green to a light brown drab.

As regulation uniforms were unsatisfactory for field conditions in Afghanistan, the officers in most regiments improvised more serviceable forms of clothing.

Every Indian regiment was commanded by British officers, in a proportion of some 7 officers to 650 soldiers, in the infantry. This was an insufficient number for units in which all tactical decisions of significance were taken by the British and was particularly inadequate for less experienced units.

The British infantry carried the single shot, breech loading, .45 Martini-Henry rifle. The Indian regiments still used the Snider; also a breech loading single shot rifle, but of older pattern and a conversion of the obsolete muzzle loading Enfield weapon.

The cavalry were armed with sword, lance and carbine, Martini-Henry for the British troopers, Snider for the Indian sowars.

The British artillery, using a variety of guns, many smooth bored muzzle loaders, was not as effective as it could have been, if the authorities had equipped it with the breech loading steel guns being produced for European armies. Artillery support was frequently ineffective and on occasions the Afghan artillery proved to be better equipped than the British.

Gatling gun crew in the Sherpur Cantonment: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

The army in India possessed no higher formations above the regiment in times of peace, other than the staffs of static garrisons. There was no operational training for staff officers. On the outbreak of war, brigade and divisional staffs had to be formed and learn by experience.

The British Army had, in 1870, replaced long service with short service for its soldiers. The system was not yet universally applied, so that some regiments in Afghanistan were short service and others still manned by long service soldiers. The Indian regiments were all manned by long service soldiers. The universal view seems to have been that the short service regiments were weaker both in fighting effectiveness and disease resistance than the long service.

Indian Cavalry Regiment: Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Mortimer Menpes

Winner of the Battle of Kabul 1879: The British and Indian army.

British and Indian Regiments at the Battle of Kabul 1879:

British Regiments:

9th Lancers, now the 9th/12th Royal Lancers. *

67th Foot, later the Hampshire Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment. *

72nd Highlanders, later the Seaforth Highlanders and now the Royal Regiment of Scotland. *

92nd Highlanders, later the Gordon Highlanders and now the Royal Regiment of Scotland. *

Indian Regiments:

12th Cavalry

14th Murray’s Lancers

Queen’s Own Corps of Guides

5th Cavalry, Punjab Frontier Force

1st PWO Sappers and Miners

23rd Bengal Native Infantry (Pioneers)

28th Bengal Native Infantry (Punjabis)

3rd Sikh Infantry

5th Punjabis (Vaughan’s Rifles)

2nd Gurkhas

4th Gurkhas

5th Gurkhas PFF.

Account of the Battle of Kabul 1879:

The murder of Britain’s emissary in Kabul, Sir Louis Cavagnari, and his escort of Queen’s Own Corps of Guides, commanded by Lieutenant Walter Hamilton, on 3rd September 1879 provoked the second phase of the Second Afghan War. Major General Sir Frederick Roberts VC led the Kabul Field Force over the Shutargardan Pass into Central Afghanistan and, defeating the Afghan Army at Charasiab on 6th October 1879, occupied Kabul.

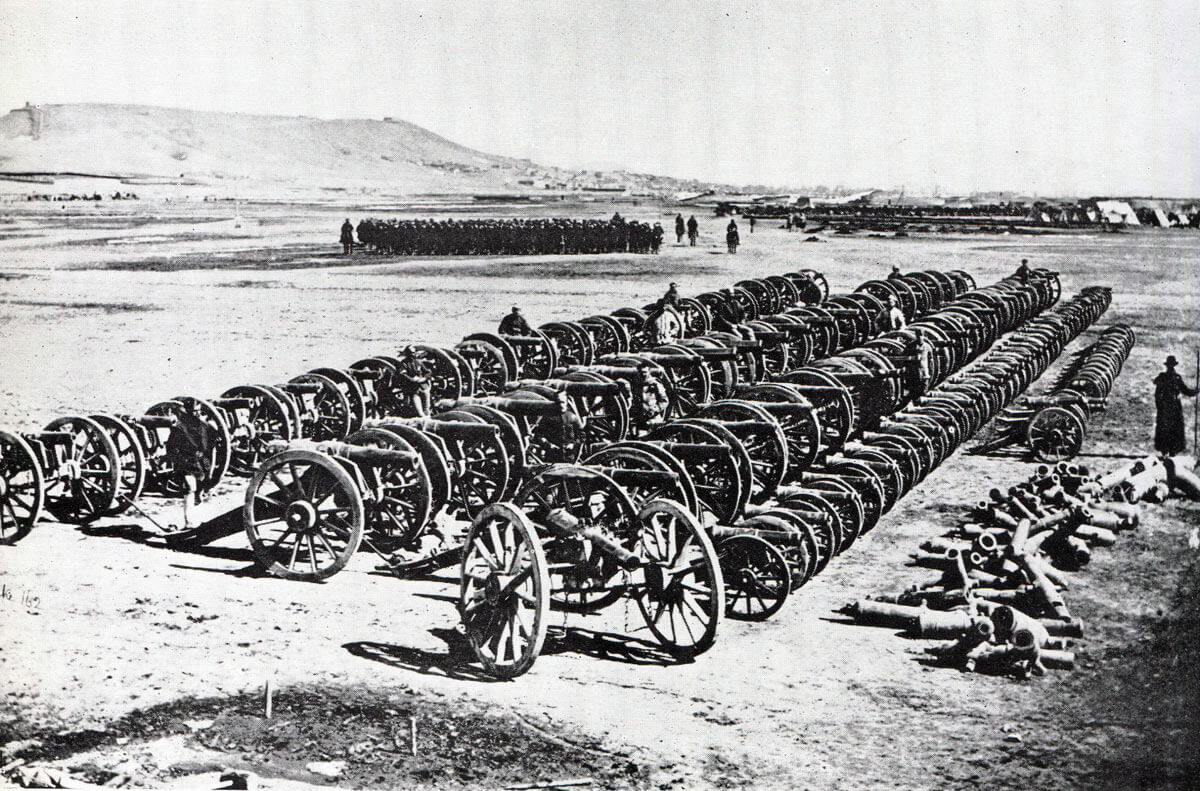

Captured Afghan guns in the Sherpur Cantonment: Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War

The British and Indian troops took over the Sherpur military cantonment north of Kabul, built by their predecessors in 1839 during the occupation of the city in the First Afghan War, rebuilt the accommodation and, finally, in early December 1839 moved into the vast compound.

Communications with India were established along the Khyber Pass route, with substantial numbers of troops deployed along its length, to keep the mountain tribes at bay.

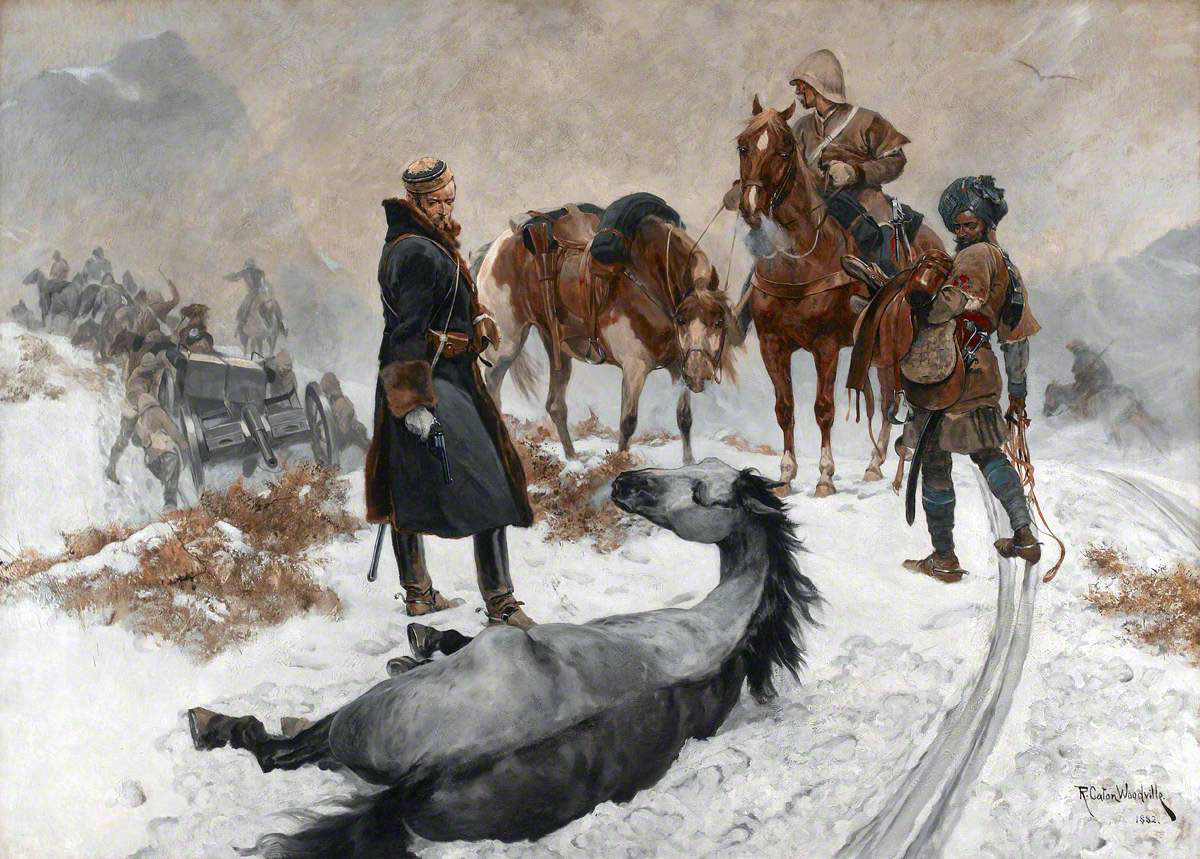

5th Punjab cavalry attacking Afghan cavalry in the Chardeh Valley: Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Roberts restored the Ameer, Yakoub Khan, to his throne and rounded up the soldiers of the mutinous Afghan Herati regiments and others reported as having stormed the British residency in the Bala Hissar and killed Cavagnari and his Guides escort. Numbers were hanged, creating considerable unrest in the population and the surrounding country.

9th Lancers in England: Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Orlando Norie

Towards the end of November 1879, reports reached the British of considerable numbers of Afghan tribesmen gathering in the area to the North of Kabul, under the command of Mohammed Jan, who had declared Musa Jan to be the new Ameer of Afghanistan in place of Yakoub Khan, widely seen as a puppet of the British.

Roberts sent two forces into the area of the Chardeh Plain to the North of the city, under Brigadier-Generals Baker and Macpherson, intending to catch the Afghans in a pincer movement. After several days of hard fighting in and around the Chardeh Plain, culminating on 11th December 1879 in a series of near disastrous engagements, the two forces managed to pull back to the Sherpur Cantonment, lucky that they had escaped from the enveloping mass of Afghan tribesmen. In one incident, the Royal Horse Artillery lost several guns in a ravine, although they were recovered later.

An aggressive leader, Robert’s view was that the Afghans should always be attacked, almost regardless of their strength. The lack of effective intelligence left Roberts in ignorance of the scale of the Afghan uprising. On this occasion, the overwhelming Afghan numbers came close to inflicting a disastrous defeat on the British and Indian force.

While some work had been carried on the defences of the Sherpur Cantonment, much remained to be done. With the threat from Mohammed Jan increasing day by day, with tens of thousands of Afghans flocking to join the uprising, the British and Indian troops toiled to complete the defences.

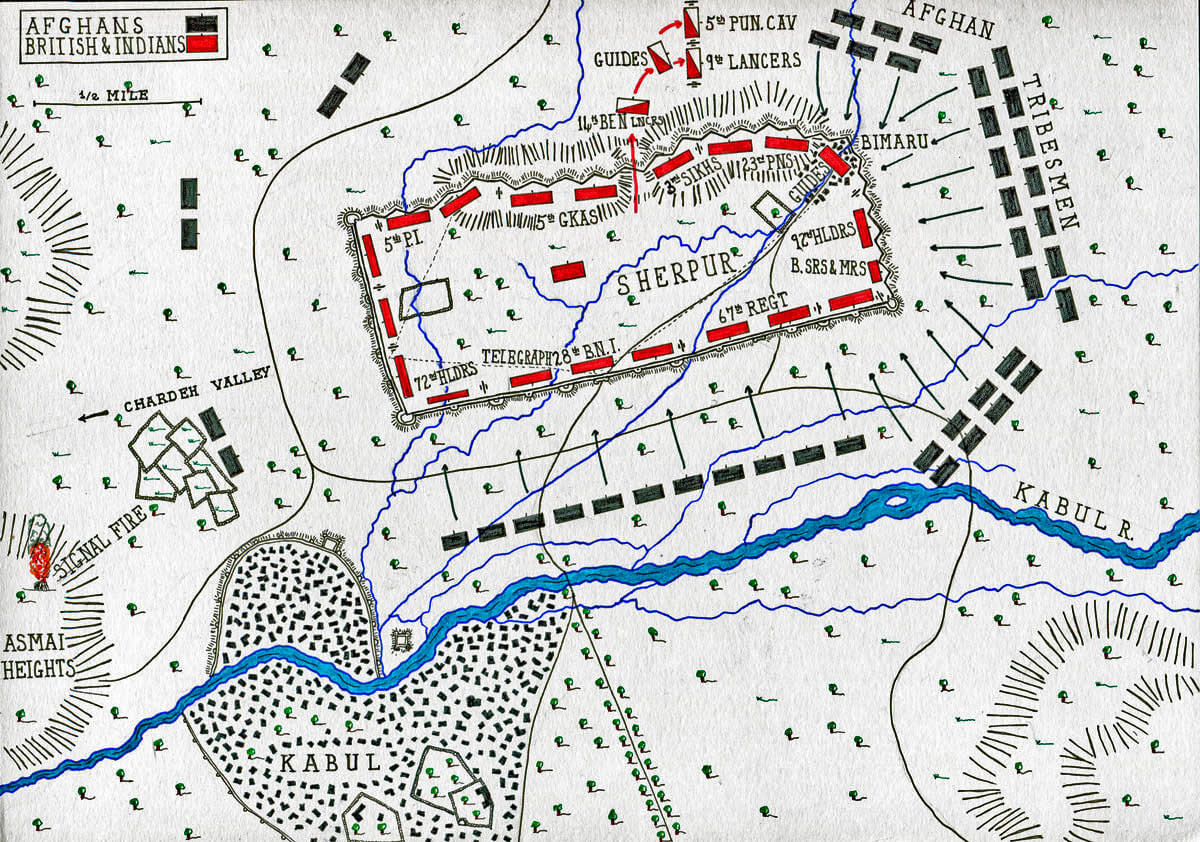

The Sherpur Cantonment, a large rectangular encampment to the north of Kabul, had been built by the British and Indian army in the First Afghan War, within a five-mile outer perimeter. The mile and a half long south wall was complete. The west wall was near completion. The northern side of the cantonment rested on the Bimaru Heights, where, in 1841, so much skirmishing had taken place and relied entirely on the heights themselves for its fortification. The east wall reached to the area of Bimaru Village and petered out.

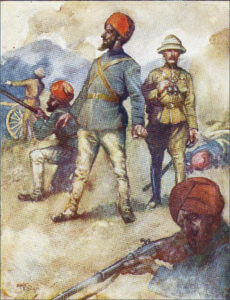

General Roberts’ Sikh Orderly covering the general: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

Mud towers were built along the heights and the village fortified. At one point, a ditch was dug and filled with captured Afghan guns and wire entanglements. An extensive telegraph system provided communications across the cantonment.

Robert’s artillery comprised twelve field guns, eight mountain guns and two Gatling guns with a small number of usable Afghan guns, which were distributed around the perimeter.

The 72nd Highlanders held part of the south and west walls. Major General Hills held the rest of the west wall and half the heights with 5th Punjab Infantry, 3rd Sikhs and 5th Gurkhas. The 23rd Pioneers held the eastern end of the heights. The Guides held the north-eastern corner around Bimaru village.

Companies from the 92nd Highlanders, 67th Foot, 28th Bengal Native Infantry and a company of Bengal Sappers and Miners held the east wall and the end of the south wall. General Roberts’ headquarters was in the west wall.

Mohammed Jan’s hordes of tribesmen hovered around the cantonment, but lacked the training and equipment to conduct a full siege.

On 17th December 1879, the British and Indian cavalry moved out of the main gate and patrolled around the cantonment walls. Provoked by this display of bravado, the Afghans gathered on the Asmai and Siah Sang Heights, to the south west and south-east, where they were bombarded by the British artillery.

On the evening of 18th December 1879, it snowed hard, causing the Afghans to disperse to Kabul for the night. Over the next few days the British and Indian troops undertook a sortie from the cantonments to capture a neighbouring fort, but otherwise awaited events.

Abattis surrounding the Sherpur Cantonment with Afghan guns in the ditch: Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War

On 21st December 1879, Brigadier General Charles Gough, commanding the First Brigade of Bright’s Second Division and already advancing towards Kabul, received, at Jagdalak, a message from Roberts ordering him to march for the Sherpur Cantonment with his brigade without delay, a move he promptly began.

Gough’s march towards Kabul finally provoked the mass attack on the cantonment that the British and Indians both hoped for and feared. Hoped for, because a decisive repulse of the assault would break up the mercurial Afghan army and feared, because the Afghans might penetrate the defences, in which case it would be all up with the heavily outnumbered garrison.

5th Gurkhas, Punjab Frontier Force: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War

On 22nd December 1879, Roberts received intelligence that the attack would be launched the next day, information that proved correct. Afghans gathered from all over the north-east of the country for the battle that was expected to destroy the invading army of British and Indians, just as their predecessors had been destroyed at the Battle of Gandamak in 1842.

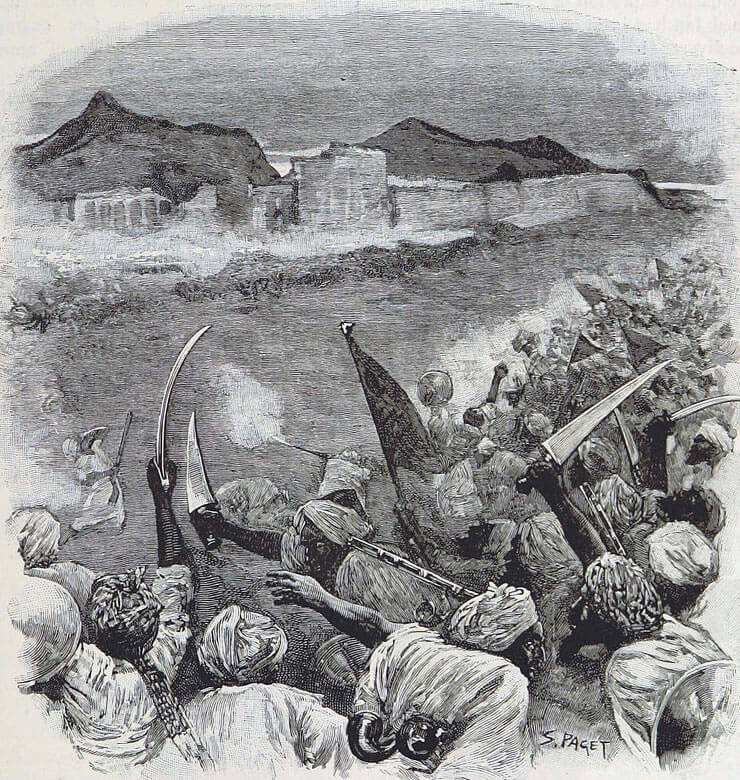

The attack was signalled before dawn by an enormous bonfire, lit on the Asmai Heights by a militant cleric, dramatically lighting up the area of the cantonment.

92nd Highlanders in the lines at the Sherpur Cantonment: Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Skeoch Cumming

50,000 Afghans, headed by white clothed Ghazis, fanatical religious leaders, rushed the cantonment fortifications. The garrison guns illuminated the area with star shells as the defending infantry poured volleys into the attacking tribesmen.

By dawn on 23rd December 1879, the attack was in full flood against the west, south and east walls, with the emphasis on the east side and Bimaru village. Only in the north-east corner did the Afghans make any lodgement. The hard-pressed Guides were reinforced by companies of Sikhs from the neighbouring heights which had not been attacked.

Afghan attack on the Sherpur Cantonment: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War: print by S. Paget

After reaching a peak of ferocity between 10am and 11am, the attack generally slackened, the Afghans returning to the assault many times, but with diminishing enthusiasm.

At around 11am, Roberts sent a force of guns and cavalry through the gap in the Bimaru Heights, to open a bombardment on the right flank of the Afghans attacking the village. Under this fire, the attackers withdrew.

9th Lancers attacking at the Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War: print by S. Paget

At around midday, the British and Indian cavalry issued from the cantonment and began the work of dispersing the remaining Afghan forces and pursuing the retreating tribesmen, while the infantry cleared the villages around the cantonment. No quarter was given to Afghans found with weapons.

On the morning of the 24th December 1879, Roberts was preparing to eject the Afghan tribesmen from Kabul city, when he received news that Mohammed Jan’s enormous army had completely dispersed.

‘Cruel to be kind’: Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Despite pursuit by the British and Indian cavalry, Mohammed Jan and his entourage escaped to Ghuznee.

Casualties at the Battle of Kabul 1879:

British and Indian casualties were 33. General Roberts estimated that the Afghan casualties, almost all killed, were 3,000.

Second Afghan War medal with clasps for Kandahar, Kabul and Charasia and Kabul and Kandahar Star: Battle of Kabul December 1879 in the Second Afghan War

Follow-up to the Battle of Kabul 1879:

The British and Indian governments, relieved at the success of the battle, now required the enormous expense of the Afghan War to be brought to an end. Over the following six months, a new Ameer was found in Abdurrahman and preparations made to withdraw the army to India. In the spring of 1880, Major General Stewart would march from Kandahar and take Ghuznee and the combined forces would withdraw to India, by the Khyber route. Kandahar would be created as a separate state and a British/Indian garrison retained there.

However, the British and Indian armies still had three hard battles left to fight, with the outbreak of serious trouble in Southern Afghanistan.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Kabul 1879:

- As a result of the experiences of the cavalry in the Chardeh Valley fighting, General Roberts recommended that the arrangements for carrying sword and carbine be reversed. Prior to the battle, the sword was carried on the trooper’s belt and the carbine in a saddle bucket. A number of British and Indian cavalrymen were unhorsed in the fighting. They found they were impeded by the sword at their waist, which restricted their movements and was of little use as a dismounted weapon. Most of these men were separated from their mounts, making their carbines, the weapons they most needed, inaccessible. By the new arrangement, the sword was hung from the saddle and the carbine was worn slung on the trooper’s back. A dismounted cavalryman would no longer be tripped up by his sword and would have his firearm immediately available. The arrangement for sword and carbine before the change can be seen in the illustration of the 9th Lancers above.

References for the Battle of Kabul 1879:

The Afghan Wars by Archibald Forbes

The Road to Kabul; the Second Afghan War 1878 to 1881 by Brian Robson.

Recent British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Second Afghan War is the Battle of Charasiab

The next battle of the Second Afghan War is the Battle of Ahmed Khel

To the Second Afghan War index