General Graham’s notable victory, also known as the Battle of Chiclana, over the French during the march to Cadiz on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Baron Lejeune

17. Podcast of the Battle of Barrosa: fought on 5th March 1811 during the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcast

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Busaco

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Campo Maior

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of Barrosa: 5th March 1811

Place of the Battle of Barrosa: east of Cadiz in Southern Spain.

Combatants at the Battle of Barrosa: British, Portuguese and Spanish against the French.

General Sir Thomas Graham: Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

Commanders at the Battle of Barrosa: The nominal commander of the British, Portuguese and Spanish army was the Spanish General La Peña. The British officer, Lieutenant General Thomas Graham, conducted the battle.

The French were commanded by Marshal Victor.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Barrosa:

The British, Portuguese and Spanish force commanded by General La Peña comprised 15,000 troops.

General Graham commanded 5,200 British and Portuguese troops.

9,800 Spanish troops were present, but few of them took any part in the fighting.

The French force that attacked the British and Portuguese contingent comprised 7,000 troops.

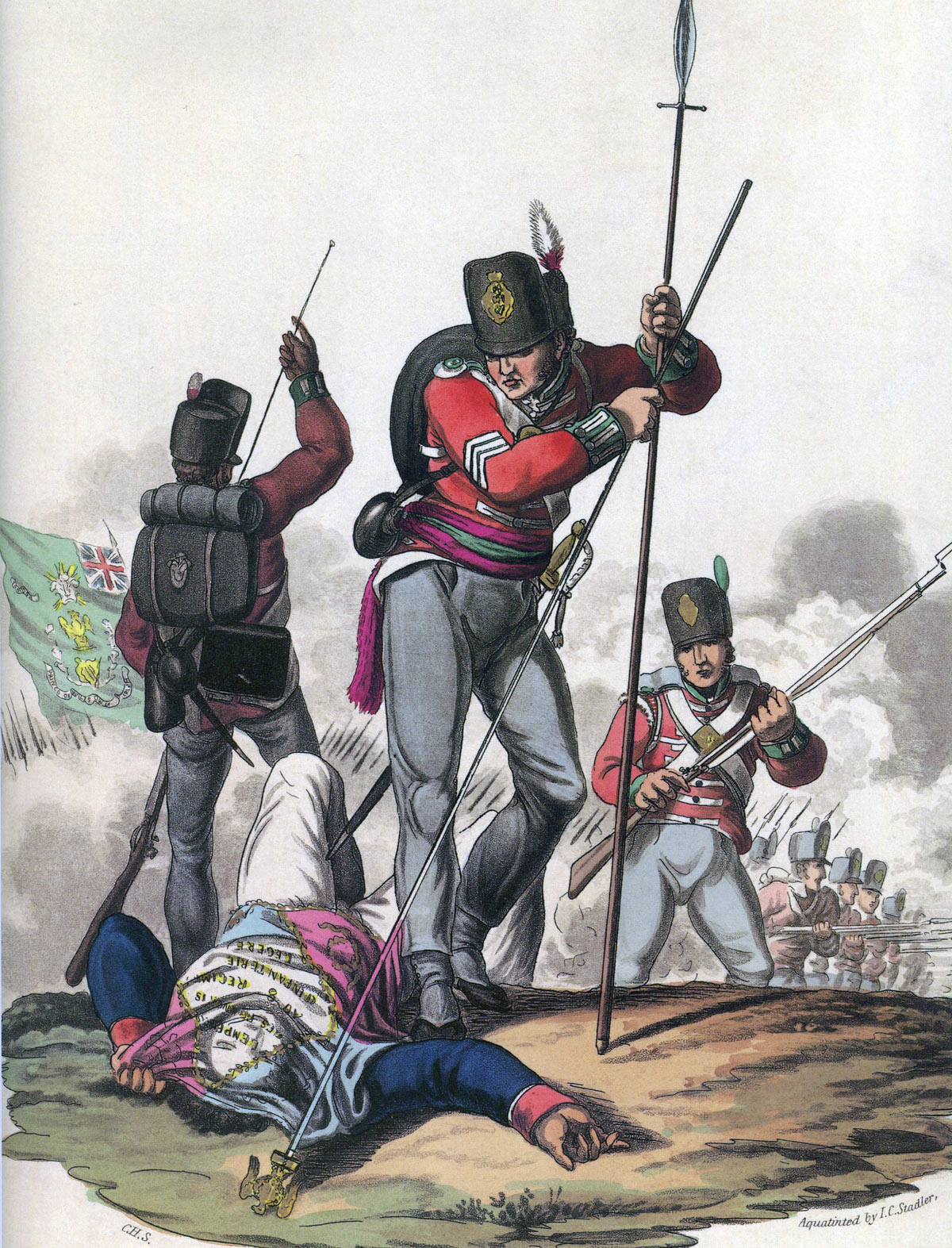

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Barrosa:

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers, and stovepipe shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments wore dark green jackets and trousers.

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

Highland regiments wore the kilt with red tunics and black ostrich feather caps.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light cavalry was increasingly adopting hussar uniforms, with some regiments changing their titles from ‘light dragoons’ to ‘hussars’.

The King’s German Legion was the Hanoverian army in exile. The owed its allegiance to King George III of Great Britain, as the Elector of Hanover, and fought with the British army. The King’s German Legion comprised both cavalry and infantry regiments. King’s German Legion uniforms mirrored the British.

The Portuguese army uniforms increasingly during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe, and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry, the horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket. The musket could be fired at three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for a hundred metres or so. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, which fitted the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, and a sword bayonet.

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who invented it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was not able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create his powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns with the speed of the French columns of infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

British 47th Regiment: Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Winner of the Battle of Barrosa:

The Battle of Barrosa took place during a raid by the Spanish and British/Portuguese force on the French siege works to the east of the southern Spanish city of Cadiz.

The aim of the raid, to inflict damage on, if not destroy, the French siege works was not achieved, but heavy casualties were inflicted on the two French divisions involved in the battle and the British, Portuguese and Spanish force was able to return to Cadiz unimpeded. The British consider the battle a victory.

British Third Foot Guards: Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

British order of battle at the Battle of Barrosa:

General Officer Commanding: Lieutenant General Thomas Graham

1 Squadron of King’s German Legion Hussars

1st Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Dilkes

2nd/1st Guards, 2nd/Coldstream Guards (2 companies),

2nd/3rd Guards (3 companies), 3rd/95th

Rifles (2 companies).

2nd Brigade: commanded by Colonel Wheatley

1st/28th Foot (less flank companies), 2nd/67th

Foot, 2nd/87th Foot

Gibraltar Flank Battalion formed from 1st/9th Foot, 1st/28th

Foot, 2nd/82nd Foot

Cadiz Light Battalion. Formed from 2nd/47th Foot, 3rd/95th

Rifles.

Portuguese Flank Battalion formed from 1st/20th and 2nd/20th

Line Regiment.

Artillery: commanded by Major Duncan

10 guns of Hughes’ and Shenley’s batteries.

General Ruffin, French divisional commander at the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

French order of battle:

Marshal Victor

General Vilatte’s Division

General Ruffin’s Division

9th Light, 96th of the Line, 24th of the Line and 6 guns

General Leval’s Division

54th of the Line, 8th of the Line, 47th of the Line and 10 guns

Background to the Battle of Barrosa:

In January 1810, Joseph Bonaparte, the French king imposed on Spain by the Emperor Napoleon with Marshal Soult advanced into the southern Spanish province of Andalusia with a French army and captured Seville, the city from where the Spanish Cortes, or supreme council, had been directing the war against the French invaders of Spain.

Soult delayed the further French advance on the important port of Cadiz, 50 miles to the south of Seville, giving time to the Spanish Duke of Albuquerque to slip into the city and hold it against the French.

Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by J.J. Jenkins

Cadiz, reached by an isthmus, was impregnable when fully garrisoned, as it now was.

Soult began a desultory siege of Cadiz, while Joseph returned to Madrid.

The garrison of Cadiz was increased by further Spanish, British and Portuguese troops, brought in by sea by the Royal Navy.

The British and Portuguese contingent was commanded by Lieutenant General Thomas Graham.

In early 1811, Soult took a substantial part of his Andalusian army north to attack the Spanish border town of Badajoz, in an attempt to relieve Massena’s Army of Portugal, in considerable difficulties before the Lines of Torres Vedras outside Lisbon.

The Spanish and British commanders in Cadiz decided to seize the opportunity of Soult’s absence to disrupt the French siege works outside Cadiz with an attack on the French rear.

The command of the sea exercised by the British Royal Navy made this possible.

General Graham and the British and Portuguese contingent took ship along the coast to Algeciras, across the bay from Gibraltar. Graham was joined by troops from the Gibraltar garrison, including a battalion formed from the flank companies (grenadier and light companies) of the garrison, commanded by Major Browne of the 28th Foot.

Spanish Regiments of Toledo and the Walloon Guards: Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Denis Dighton

General La Peña arrived with a Spanish force and, having a larger contingent, took command of the combined army.

La Peña ordered the army to march along the coast westwards towards Cadiz.

Criticism is made of La Peña that he marched the troops too hard and kept changing their destination.

Rather than fulfilling the purpose of the expedition, which was to destroy as much of the French siege works outside Cadiz as possible, La Peña resolved to march along the coast and back into Cadiz, with the assistance of the Spanish force waiting on the far side of the Santi Petri River.

The French Marshal Victor moved to intercept La Peña.

General La Peña left directions with his subordinate in Cadiz, General Zayas, that he would be beginning his assault on the rear of the French siege lines on 3rd March 1811.

La Peña ordered Zayas to carry out an attack across the River Santi Petri from Cadiz, to take the French in the front while La Peña’s army attacked them in the rear.

Zayas crossed the River Santi Petri on 2nd March 1811, but due to La Peña’s incompetent conduct of the march from Tarifa, his army was not in position to conduct his part of the attack.

Victor struck at Zayas’s force and drove it back across the river into Cadiz.

Following this action, Victor deployed his army, with Vilatte’s division in place to prevent Zayas making another crossing from Cadiz and prevent La Peña from reaching the River Santi Petri, positioning his remaining two divisions, commanded by Leval and Ruffin at Chiclana, ready to intercept La Peña’s army by attacking its right flank as it approached the River Santi Petri.

Map of the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

The Battle of Barrosa:

La Peña’s army comprising his Spanish troops and Graham’s smaller British and Portuguese division, was passing the Barrosa Hill, known as the Cerro de Porco, marching west along the coast towards Cadiz, when his cavalry advanced guard warned him of the presence of Villatte’s troops at the Torre de Bermeja, a quarter of a mile short of the River Santi Petri.

La Peña launched an attack on Vilatte and was repelled until Zayas again crossed the river in Vilatte’s rear, causing Vilatte to withdraw northwards across the Almansa Creek and take up a position defending the ford over the creek.

Spanish General and his staff: Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Denis Dighton

Following this apparent success, limited as it was, La Peña decided to move his whole force further forward towards the River Santi Petri.

Graham objected to this course, as it would entail abandoning Barrosa Hill and enable the French to block the force into a confined area, whereas continuing to occupy the hill would deter the French from attacking.

Coldstream Guards at the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

La Peña agreed to leave Whittingham’s Spanish cavalry with a number of Spanish infantry battalions and Browne’s British battalion to defend Barrosa Hill.

The rest of the force was ordered to march to Bermeja, a mile short of the River Santi Petri.

While La Peña’s Spanish formations marched closer to the sea, Graham led his British troops by a route further to the north, towards Chiclana, through the thick pine-woods that lay to the north-west of the Barrosa Hill.

Graham followed the path through the pine forests taken by the artillery of the Spanish officer Lardizabal, with Wheatley’s Brigade in the lead, followed by Dilkes’ Brigade and the artillery and the 95th Rifles in the rear.

The pine-woods were thick and rendered the keeping of formation difficult.

Victor, the French commander, was aware that there were Spanish troops at Bermeja, more on the banks of the River Santi Petri and a further force on Barrosa Hill, but he did not know how many were in each place.

In particular, Victor was without information as to where the British contingent lay.

Victor decided that he had the opportunity to take Barrosa Hill and shut La Peña’s army into the narrow coastal stretch, as Graham feared.

Victor’s two divisions marched south from Chiclana, Leval’s Division on the road and Ruffin’s Division taking a route immediately to the east around a lake known as Laguna del Puerco.

French infantry advancing at the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by R. Granville Baker

Victor ordered his cavalry, some 500 troopers, to march around Barrosa Hill by the south-east, to the coast and Ruffin’s Division, amounting to 2,500 men, to take the summit of the hill from the east, while Leval’s Division of 4,000 men advanced on the hill from the north.

As this attack developed, Brown’s battalion and a squadron of the King’s German Legion 1st Hussars were on the southern side of Barrosa Hill recovering from the exertions of the day’s marches, significantly extended by the frequent changes of plan imposed on the troops by the indecisive and timorous La Peña.

La Peña was himself with the troops on Barrosa Hill, when a German hussar galloped in and announced the imminent approach of the French troops marching from Chiclana.

La Peña’s Spanish battalions set off along the coast road to the west, towards Bermeja, while Whittingham held the coast road with his cavalry and some Spanish infantry battalions.

One of the squadrons of the 1st King’s German Legion Hussars was falling back before Leval’s Division.

This squadron presented so threatening a demeanour to the French infantry, that Victor halted the division and ordered the battalions into square, before continuing the advance south.

Ruffin’s Division was not so impeded and moved swiftly onto the slopes of Barrosa Hill, the cavalry in advance, the infantry in column followed by the artillery.

Spanish guns opened fire on Ruffin’s Division, but La Peña quickly ordered a retreat and for a time two of these guns were abandoned, before being recovered.

Whittingham retained two Spanish regiments to defend the coastal road, the Ciudad Real and the Walloon Guards.

Two battalions from these regiments moved to the summit of the hill, while the remainder drove off the French cavalry pillaging the Spanish baggage, piled on the road at the bottom of the hill.

As the baggage followed the rest of the Spanish troops, these regiments fell back along the coast road, to a position from where they kept the French skirmishers at bay.

British First Foot Guards at the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Once La Peña began his march to the west, Browne set off with his battalion to the north-west, across the heavily wooded Barrosa Hill, to join the rest of Graham’s British and Portuguese Division and warn him of the French approach.

Graham’s division was clearing the thickly wooded slopes of Barrosa Hill, marching to the west, when a patrol of the 1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion came in with the warning that French troops were marching towards the hill from the north.

In the meantime, Ruffin’s Division reached the lower slopes of the Barrosa Hill and turned west to march up to the summit.

There, Browne’s battalion was seen hurrying away through the woods and a squadron of French cavalry pursued them.

Browne formed square to hold off the French cavalry, but a squadron of German hussars intervened and drove the French cavalry back, enabling Browne to continue on into the forest.

Browne sent several messengers to Graham, warning him of the presence of the French on Barrosa Hill in strength.

On receipt of this information, Graham turned his division about to return and attack the French on Barrosa Hill, in the belief that La Peña’s Spanish troops would need assistance in defending the hill against the French.

Riding out of the wood, heading east towards Barrosa Hill, Graham encountered Browne himself, who informed him that the Spanish were in full retreat and from the edge of the wood Graham could see that this was so, the Spanish regiments streaming along the coastal road to the west.

Graham could also see Ruffin’s Division on Barrosa Hill and Leval’s Division on the British left flank.

Graham decided to attack the two French divisions, while they were still advancing and before they could unite.

Graham’s Division was not in good order for the attack, after a long series of exhausting marches and now moving through the dense pine forest.

There was not the time to put the troops in order before launching the attack and the various regiments were left to force their way back out of the forest and begin the assault as best they could.

Spanish troops: Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Suhl

Browne’s battalion turned about and marched back up Barrosa Hill to attack Ruffin’s Division.

This put Browne in the centre of Graham’s line and well in front of it, with the rest of Dilkes’ Brigade coming up on his right and Wheatley’s Brigade on his left.

Ruffin’s Division was forming up on the summit of Barrosa Hill, when Browne’s battalion appeared from the woods at the bottom of the western side of the hill.

A broad ravine impeded Browne’s advance and, coming under heavy musketry with grape shot from Ruffin’s guns and suffering heavy casualties, Browne’s men took cover and could not for the moment be persuaded to resume the attack, but continued to fire on the French.

On the left of Browne’s battalion, Captain Norcott’s two companies of the 95th Rifles emerged from the woods with the British guns.

These guns took up position between the two British brigades and opened fire on Leval’s advancing division.

Dilkes’ Brigade came up on the right of Browne’s battalion, in front of Ruffin, while Wheatley’s Brigade was advancing on the left, to confront Leval.

British Foot Guards attacking at the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

In Dilkes’ Brigade, the First Guards came into action on the left, followed by companies of the Third Guards to their right and then companies of the 67th Regiment.

Two companies of the 47th Regiment were attached to the guns for their protection, while other companies had become detached from their parent battalions in the dense forest and joined in the attack wherever they happened to contact the French line.

In spite of the disorder caused by the advance through the woods, all the British battalions attacked the two French divisions without pausing to reform.

The British guards were subjected to a storm of artillery fire but did not pause, as they advanced on the French 24th of the Line, with two battalions of grenadiers and the 96th of the Line in support.

The French regiments were driven back.

Victor was present with Ruffin’s Division and brought forward the grenadiers and the 96th to reinforce the 24th.

Browne’s battalion, no longer subject to the heavy fire that had restrained their attack, rushed forward and poured a volley into the French 96th.

At this point, the British 67th and Norcott’s riflemen came into the fight, out flanking the French left wing.

The exchange of musketry between the infantry is described as ‘one-sided’, as the French regiments were in column and could not match the volleys of the British regiments firing ‘in line’.

British infantry attacking at the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

Ruffin was wounded and a number of his officers, who were inevitably greatly exposed, were killed or wounded.

The French troops out-flanked and out-shot began to waver.

The British troops were ordered to charge and rushed forward, driving the disordered French division down the hill and capturing two guns.

On the British left, the attack was being pressed against Leval’s Division.

The initial assault was by the skirmishing line of Barnard’s companies of the 95th Rifles and the Portuguese 20th Caçadores.

The heavily wooded area enabled the British skirmishers to reach within 300 yards of the French troops before opening a heavy fire.

In addition, the British guns, brought forward to the centre of the British line, were concentrating their fire on Leval’s Division.

Leval’s regiments were in the process of deploying from the squares caused by the threat from the enterprising squadron of King’s German Legion 1st Hussars, making them particularly vulnerable to the British fire and preventing them from responding fully.

Behind Barnard’s skirmishing line, Wheatley’s regiments were emerging from the woods and forming line, although under a heavy fire from Leval’s guns.

Graham brought up the Coldstream Guards to cover the advance of two British batteries, which unlimbered at close range and began to ply the French infantry with grapeshot and shrapnel.

Finally deployed from their squares into column, Leval’s infantry began to advance, the French 54th of the Line on the right and the 8th of the Line on the left, with a battalion of the 45th in the reserve.

The French advance drove away Barnard’s skirmishers and continued towards the British line.

Wheatley’s Division confronted the 2,700 men of Leval’s Division with 1,400 men, but they were formed in a line that extended beyond Leval’s flanks on each wing.

Hugh Gough, commander of the 87th Regiment at the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

On Wheatley’s left was the 28th Regiment (less its flank companies which were with Browne), then two companies of the Coldstream, the 87th Regiment commanded by Major Hugh Gough and the 67th Regiment (less the companies that found themselves on the right wing with Dilkes’ Brigade).

On Wheatley’s right, the British guns, with their escort of two companies of the 47th, now advanced to within 600 yards of the French line.

The French regiments fired volleys as they advanced, but due to the different rates of fire between the French battalions, their line advanced at an uneven rate, making it convex. The first regiments to clash were Gough’s 87th with the 8th of the Line.

Fortescue describes the 87th as firing three times as many rounds as the French battalion, which quickly recoiled from the contest and broke on another battalion of the 8th.

Graham shouted for the British regiments to cease firing and charge.

The Guards and the 87th immediately threw themselves on the French columns with the bayonet, quickly joined by the 67th and the Coldstream at either end of the line.

The French regiments were in a state of collapse and quickly suffered terrible casualties at the hands of the British Guards, the Irish 87th and the other British regiments.

Sergeant Masterson of the 87th Regiment taking the Eagle of the French 8th of the Line at the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Hamilton Smith

The eagle of the French 8th Regiment of the Line became the centre of a desperate struggle, as the soldiers of the Irish 87th fought to take the standard and the French escort fought as hard to defend it.

Finally, Sergeant Masterson of the 87th captured the standard with its eagle crest.

As the desperate struggle between the two lines came to a climax, Leval ordered up the battalion of the 45th of the Line to relieve his other hard-pressed regiments.

Seeing the approaching 45th, Gough managed to collect a small party of the 87th and attacked the advancing French battalion.

The 45th numbered some 700 men and had taken no part in the battle, but they were demoralised at the sight of the terrible beating the other battalions of their division were taking at the hands of Graham’s troops.

As Gough’s small party came within 50 yards of the 45th, the French battalion broke and fled.

On Wheatley’s left, the centre companies of the 28th came into line and advanced on a battalion of the 54th, which the 28th outflanked.

The 28th did not fire until close to the 54th and its volley forced back the French battalion.

The 28th then delivered three charges, the third of which broke the 54th, which turned and fled to the protection of the grenadier battalion covering the withdrawal of Leval’s defeated regiments.

Both French divisions were now in retreat.

Dilkes’ Brigade halted on the top of Barrosa Hill and reformed, too exhausted and depleted by casualties to follow up the defeated French with any speed.

Victor rallied Ruffin’s Division, assisted by his dragoons.

Dilkes’ Brigade resumed its advance turning to the north-east.

The French dragoons, which had been engaged with Whittingham’s force of Spanish and King’s German Legion cavalry, changed their focus of attack to the right wing of Dilkes’ Brigade, forcing the Third Guards to form square.

Ponsonby’s charge of the King’s German Legion 1st Hussars at Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

Colonel Ponsonby took command of a squadron of the King’s German Legion Hussars, which he found in advance of Whittingham’s main force and led them in an attack on the French dragoons, charging through them and then charging the guns of Ruffin’s Division and the infantry beyond, who stood firm and drove the German hussars off.

Had Whittingham committed his whole force of cavalry, he might well have routed and destroyed the remnants of Ruffin’s Division.

The two French divisions retreated towards Chiclana and, passing the Laguna del Puerco, Victor halted and reformed them behind the lake, with their flank on the pine forests.

Carabiniers of the French 9th Light at the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

The British infantry were too exhausted, after the intense activity of the previous 24 hours, to do more than follow up the French retreat for a short distance.

The British guns came up and bombarded the French out of the position adopted by Victor and the French marshal withdrew his defeated force to Chiclana.

Throughout the battle on Barrosa Hill, La Peña and his Spanish troops held aloof, leaving the British, Germans and Portuguese to fight alone.

Had, at the very least, the Spanish cavalry joined the King’s German Legion Hussars, the French losses would have been disastrous. Victor’s force might well have been destroyed.

Once the French had been driven off, Graham’s force resumed their march along the coast and crossed the River Santi Petri back into Cadiz.

No attempt was made to destroy any of the French siege works.

Casualties at the Battle of Barrosa:

The French lost 2,062 men killed, wounded or captured. Of these casualties, the 8th of the Line suffered 726, or half its compliment.

Generals Vilatte and Ruffin were wounded, Ruffin being captured.

General Rousseau was wounded and died during the night in British captivity.

The British and Portuguese suffered casualties of 1,238 men killed, wounded or captured.

British regimental casualties:

The First Guards lost 10 officers and 210 soldiers killed or wounded

The Coldstream Guards lost 3 officers and 54 soldiers killed or wounded

The Third Guards lost 2 officers and 99 soldiers killed or wounded

The Royal Artillery lost 8 officers and 46 soldiers killed or wounded

The 9th Foot lost 4 officers and 64 soldiers killed or wounded

The 28th Foot lost 8 officers and 151 soldiers killed or wounded

The 47th Foot lost 2 officers and 69 soldiers killed or wounded

The 67th Foot lost 4 officers and 40 soldiers killed or wounded

The 82nd Foot lost 2 officers and 97 soldiers killed or wounded

The 87th Foot lost 5 officers and 168 soldiers killed or wounded

The 95th Rifles lost 4 officers and 62 soldiers killed or wounded

Military General Service Medal with Barrosa clasp: Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

Medal and Battle Honour for the Battle of Barrosa:

The Military General Service Medal 1848 was issued to all those serving in the British Army present at specified battles during the period 1793 to 1840, who were still alive in 1847 and applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one or more of the clasps. There were 21 clasps available for service in the Peninsular War.

The Battle of Barrosa was one of the clasps.

The battle honour ‘Barrosa’ was awarded to the following British regiments: First Guards, Coldstream Guards, Third Guards, 28th, 67th, 87th Regiments and 95th Rifles.

Army Gold Medal:

In 1810 a Gold Medal was issued to be awarded to officers of rank of major and above for meritorious service at certain battles in the Peninsular War, with clasps for additional battles. The ‘Large Gold Medal’ was awarded to generals, the ‘Small Gold Medal’ to majors and colonels, with the medal replaced by a cross where four clasps were earned. The Battle of Barrosa was one of the battles.

Follow-up to the Battle of Barrosa:

GeneralGraham was furious at the failure of La Peña to support him and at the way the Spanish general had conducted the raid.

The Spanish Cortes awarded Graham the position of Grandee of the First Class which he refused, resigning his post as commander of the British and Portuguese forces in Cadiz and returning to the main army in Portugal.

Colours of the 87th Regiment showing the Eagle of the 8th and the Battle Honour of the Battle of Barrosa or Chiclana fought on 5th March 1811 in the Peninsular War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Barrosa:

- Baron Lejeune, the artist-general of the French Napoleonic Army, painted a striking picture of the Battle of Barrosa, under the name of the ‘Battle of Chiclana’, although he was not himself present. The picture shows the combat between Dilkes’ Brigade and the French 9th Light Regiment. General Ruffin appears on the right of the picture urging his division into battle. The picture appears on this site.

- Lieutenant General Thomas Graham of Balgowan was a Scottish Landowner and keen cricket player. While in France after the Revolution in 1789, Graham’s wife died. A French mob treated his wife’s coffin with considerable disrespect. Enraged, Graham, at the age of 45, raised a regiment at his own expense in his home county of Perthshire, the 90th Foot, becoming its colonel. The 90th became a light infantry regiment and was known as the ‘Perthshire Grey Breeks’ from the colour of the soldier’s trousers. Prevented from promotion any earlier by the Duke of York’s regulations, Graham was promoted major general at the specific dying wish of Sir John Moore. Graham subsequently became Wellington’s second in command and a peer as Lord Lynedoch.

- Judge Advocate Larpent, in his private journal, records that Graham was reputed to have stood in a river before the Battle of Barrosa, after jumping off his horse, shouting encouragement to his troops as they waded across. Some of Graham’s men called to him ‘Come, old corporal, do go and take care of yourself and get out of our way.’

- At the Battle of Barrosa, Sergeant Patrick Masterson captured the first French eagle to be taken in battle, from the French 8th of the Line, and was commissioned. One of the French regiments to take a prominent part in the Battle of Barrosa was the 45th of the Line, which was to lose its eagle to the Royal Scots Greys at Waterloo.

- Sergeant Masterson’s regiment, the 87th Foot, were known in the Peninsular for their battle cry ‘Faugh a Ballagh’, the Irish for ‘Clear the way’. Following the Battle of Barrosa, the 87th Regiment was recommended to the Prince Regent, who awarded them the title of ‘Prince of Wales’ Own Irish Regiment’ and directed that they wear an eagle on their colours and appointments.

- Major Browne led his composite flank companies battalion into the attack singing his favourite song ‘Hearts of Oak’, or so it is said.

- General Ruffin was shot in the neck, the wound leaving him paralysed. After his capture, General Graham ensured that Ruffin was cared for. Ruffin died on the voyage to England and was buried with full military honours.

- General Rousseau was found lying on the battle field with his white poodle beside him. The dog refused to allow the British soldiers to approach the general and had to be restrained in a cloak to allow the wounded officer to be moved. Rousseau died at midnight and was buried. The dog escaped and tried to dig his master’s body up. The dog was taken to General Graham who adopted him and took him home.

- Major Hugh Gough went on to command the British army in the Sikh Wars, fighting the battles of Moodkee, Ferozeshah, Sobraon, Ramnagar, Chillianwallah and Goojerat in much the same way that he fought at Barrosa, with headlong charges and overwhelming courage,

References for the Battle of Barrosa:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Busaco

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Campo Maior

17. Podcast of the Battle of Barrosa fought on 5th March 1811 during the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcast