The sudden capture by Wellington, on 19th January 1812, of Marmont’s ‘base of operations’ for the intended third French invasion of Portugal, during the Peninsular War

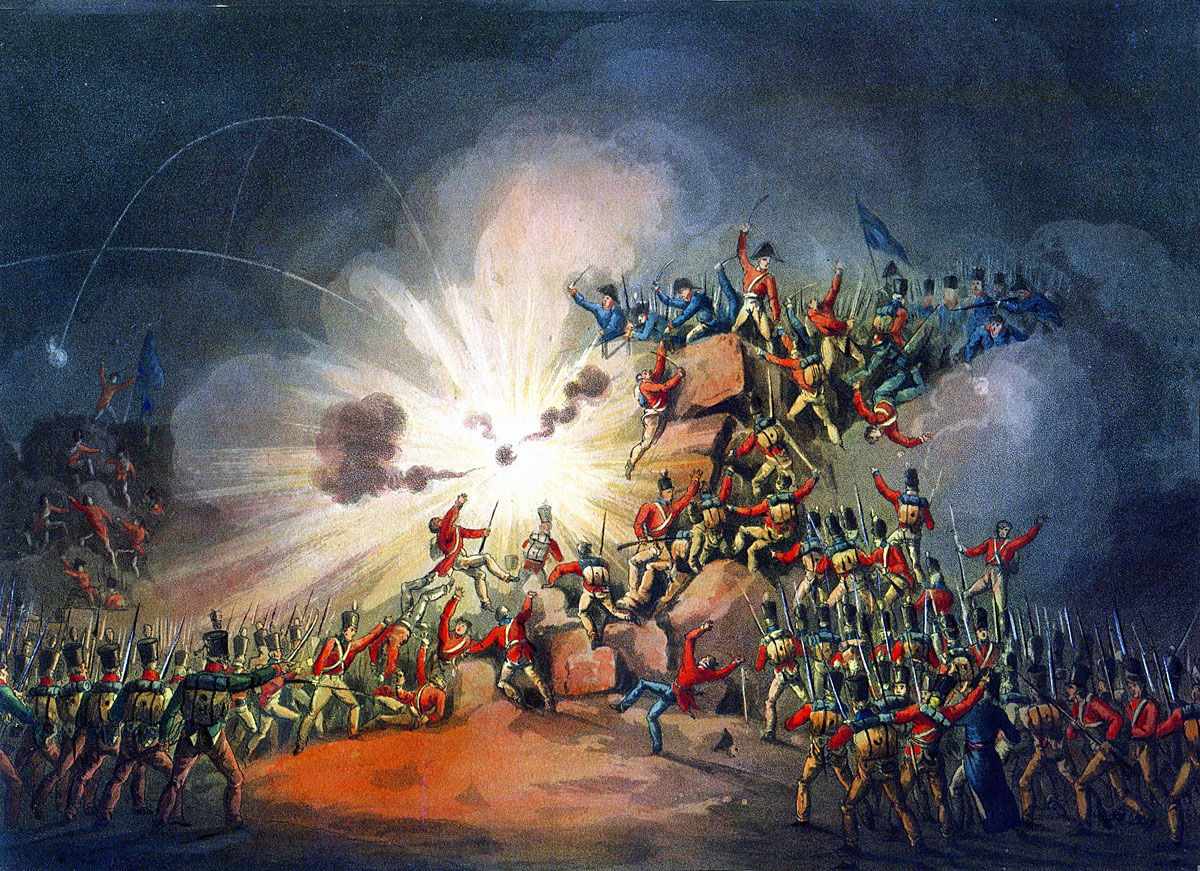

Explosion of the French magazine in the Main Breach, during the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by J.J.Jenkins

26. Podcast of the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo: The sudden capture by Wellington on 19th January 1812 of Marmont’s ‘base of operations’ for the intended third French invasion of Portugal during the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

26. Podcast of the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo: The sudden capture by Wellington on 19th January 1812 of Marmont’s ‘base of operations’ for the intended third French invasion of Portugal during the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of Arroyo Molinos

The next battle in the Peninsular War is the Storming of Badajoz

Battle: Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo: 19th January 1812

Place of the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo: In Western Spain, near the Portuguese border.

Combatants at the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo: British and Portuguese troops against the French.

Wellington giving instructions for the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

Commanders at the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo: The commander of the British and Portuguese force was Lord Wellington.

The commander of the French garrison of Ciudad Rodrigo was General Barrié.

Size of the armies at the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo:

The main formations in the assault were the Third and Light Divisions of Wellington’s army, probably around 12,000 men.

The French records show the garrison as numbering around 1,800 men. The French were well equipped with artillery, having the Siege Train of the Army of Portugal in the city.

The French garrison comprised: the 34th Light and 133rd of the Line, comprising 1,552 men, 2 companies of artillery, comprising 168 men, 15 engineers, 40 staff and 163 sick, all less 120 dead and deserted.

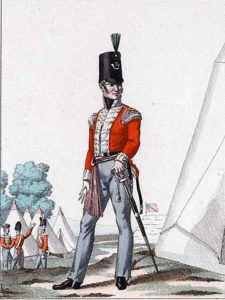

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo:

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers and shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments, the 60th and 95th, wore dark green jackets and trousers.

Highland troops wore the kilt and feather bonnets.

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light cavalry wore light blue tunics with characteristic leather helmets covered by a bearskin crest.

The Portuguese army uniforms during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

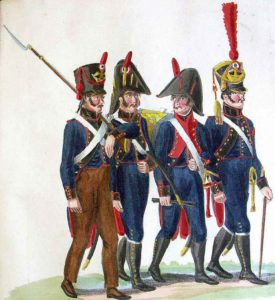

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue. Most infantry wore a shako headdress.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry. The horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket, that could be fired three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for around a hundred metres. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, fitting into the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, with a sword bayonet.

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who developed it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was not able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create a powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns, with the speed of French infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

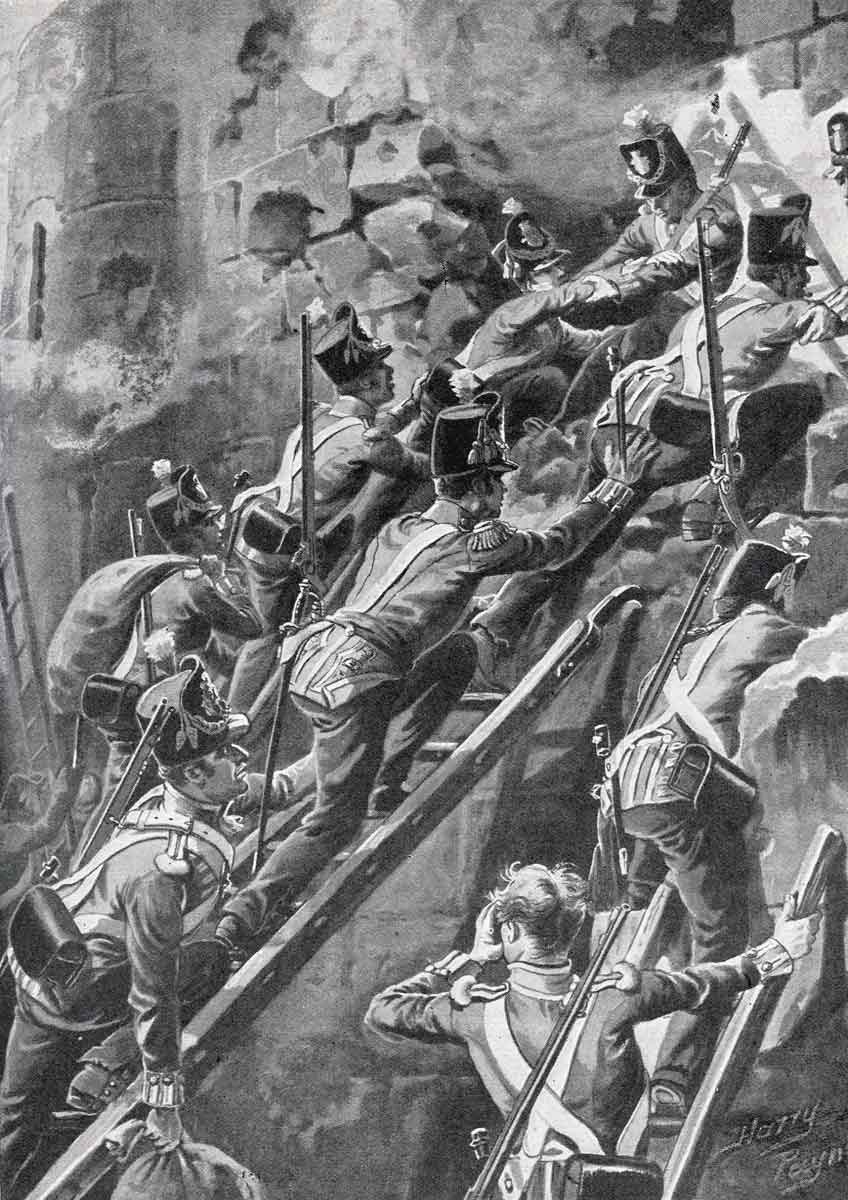

88th Connaught Rangers during the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Harry Payne

Winner of the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo:

On 19th January 1812, the British and Portuguese troops stormed the fortified city of Ciudad Rodrigo, the French garrison surrendering.

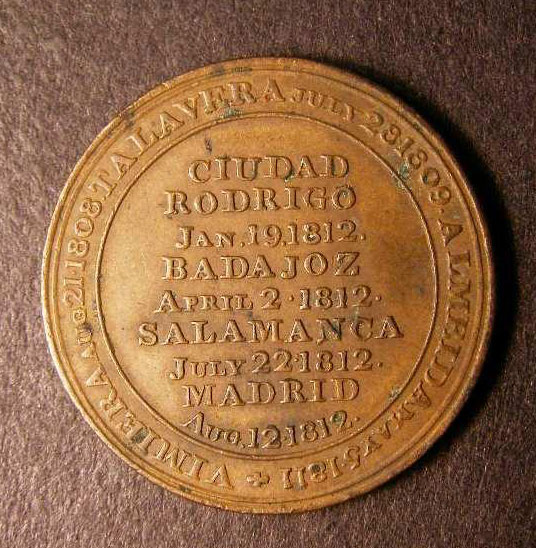

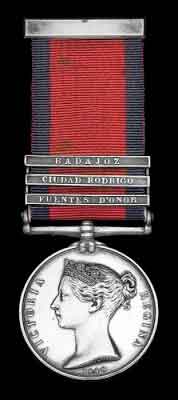

Medal commemorating the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 and other battles in the Peninsular War

Background to the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo: With the French under Marshal Marmont pushed back across the border from Portugal into Spain, at the end of 1811, Wellington’s plan was to capture the Spanish border city of Ciudad Rodrigo; situated on the River Agueda and a key base for either side, for a French invasion of Portugal or a British invasion of Spain.

At the end of 1811, the French armies across Spain were distracted by Suchet’s winter invasion of Valencia on the east coast of Spain, for which all the French commanders in Spain were required to provide reinforcements.

In December 1811, Marmont was ordered by the Emperor Napoleon to dispatch 12,000 men to Suchet and to provide a further 3,000 men to guard Suchet’s lines of communication.

At the same time, Marmont dispersed his remaining troops, while intending to march, himself, to Cuenca, between Madrid and Valencia.

The Imperial Guard was being withdrawn from Spain to take part in the Emperor Napoleon’s intended invasion of Russia.

Marmont then received further instructions, which kept him at Talavera, in the River Tagus valley, pending a move to Valladolid, north of Madrid.

On 1st January 1812, Lord Wellington issued his instructions for the attack on Ciudad Rodrigo.

The time of year led to extreme difficulties, the ground being covered in snow, causing casualties among the troops and making transport difficult.

The first step in Wellington’s attack on Ciudad Rodrigo was to build a bridge at Marialva, over which equipment and supplies could be brought from Portugal across the Azana River.

Wellington planned to ‘break ground’ (i.e. begin siege operations) outside Ciudad Rodrigo on 6th January 1812, but delays put this back and it was on 4th January 1812 that the infantry divisions designated to take Ciudad Rodrigo; the First, Second, Third, Fourth and Light Divisions, began to move forward and occupy towns around the city.

Distant view of the City of Ciudad Rodrigo: Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War

Ciudad Rodrigo:

The city of Ciudad Rodrigo stands on the north bank of the River Agueda, on an oval shaped hill that rises one hundred and fifty feet above the river.

The main city was 750 yards from west to east (along the river) and 500 yards from south to north (away from the river).

The city was surrounded by a 30-foot wall of medieval build and modern 18th Century fortifications outside that wall, except along the river frontage, where the position of the medieval wall left no room for further works.

In the south-west corner of the city, a bridge crossed the River Agueda to the southern suburbs and routes to the south.

To the north-west of the city, a stream flowed along a valley, beyond which is a ridge called the ‘Little Teson’.

Beyond the Little Teson, another valley and brook gave way to a higher and more substantial hill feature called the ‘Great Teson’.

To the north-east of the city, lay the suburbs, in a low-lying area. There were five convents around the northern boundaries of the city, two of which were to feature in the fighting; the Convent of Santa Cruz, to the west of the city and the Convent of San Francisco to the north of the city, beneath the eastern edge of the Great Teson.

As the Great Teson was higher than the city, the French built a redoubt on the south-eastern corner of the Great Teson, called the ‘San Francisco Redoubt’, after the convent over which it looked.

The French Garrison of Ciudad Rodrigo:

The French garrison of Ciudad Rodrigo numbered around 1,880 men.

The French governor of Ciudad Rodrigo was General Barrié. Marshal Marmont described Barrié as ‘a detestable officer, endowed neither with vigilance nor with resolution.’ If this was so, it is hard to see how Barrié was given the command of such a vital post, containing the siege train of the Army of Portugal.

Barrié was required to perform this duty with an inadequate garrison. The Spanish garrison from whom Marshal Ney captured Ciudad Rodrigo in 1810 numbered 5,000.

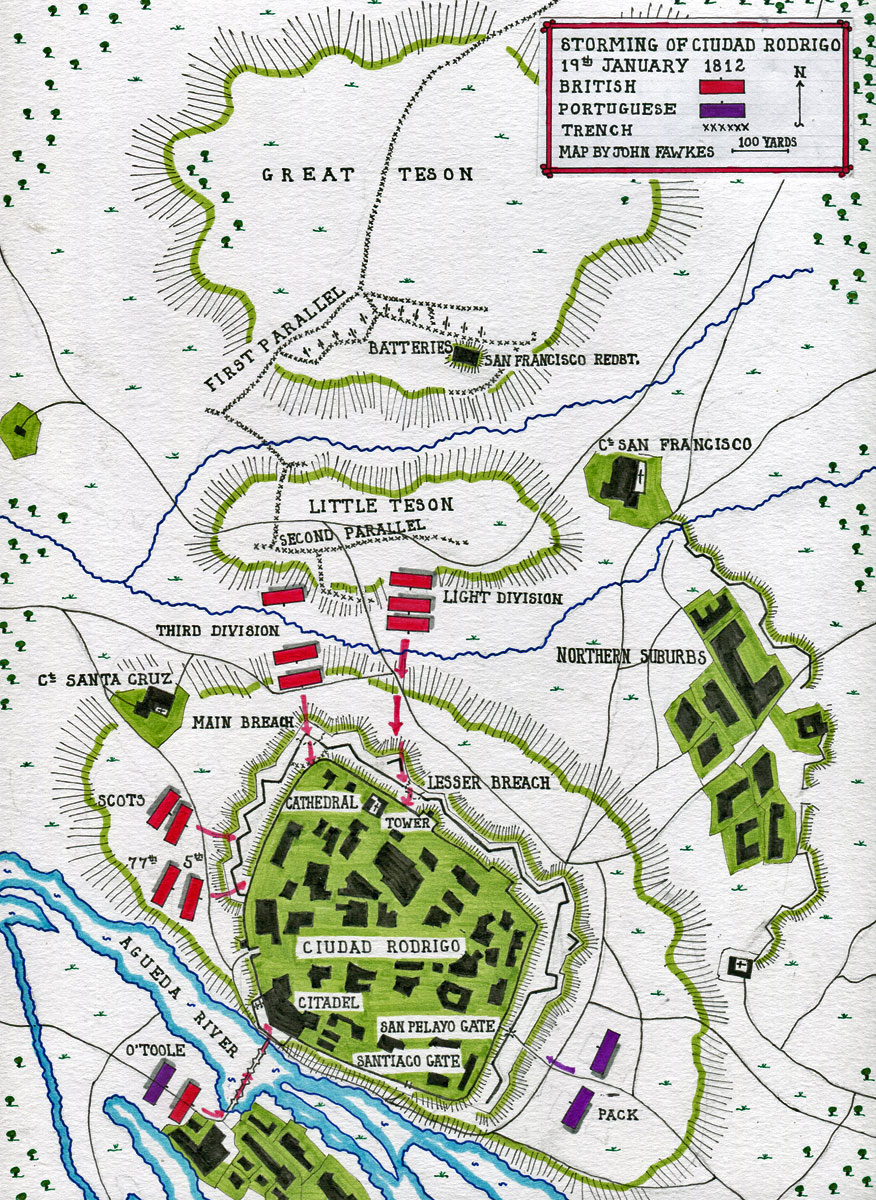

Map of the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo:

It was clear to both the besiegers and the besieged that the attack on the fortifications must be launched from the Great Teson.

Lord Wellington made a show of examining the city from all angles, but it is unlikely that the French were misled by this ploy.

Major John Colborne of the 52nd Light Infantry: Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War

At 8pm on 8th January 1812, a party from the Light Division commanded by Major Colborne, comprising 10 companies of the 43rd, 52nd and 95th Regiments and the 1st and 3rd Portuguese Caçadores, formed up beneath the crest of the Great Teson and advanced to attack the San Francisco Redoubt.

Using ladders, a storming party entered the redoubt, covered by the fire of their comrades. The redoubt was taken in 20 minutes, with all but 7 of the French garrison of 55 men captured, at a loss of only 3 killed.

The French expectation was that the San Francisco Redoubt would hold out for 5 days.

Immediately after the capture of the redoubt, construction was begun of the First Parallel on the site of the trench dug by the French in the 1810 siege of the city.

The French garrison, while short on numbers, was well equipped with artillery manned by experienced and dedicated gun crews. As soon as the few members of the redoubt’s garrison to escape reached the city, a heavy bombardment was opened on the redoubt and the Great Teson.

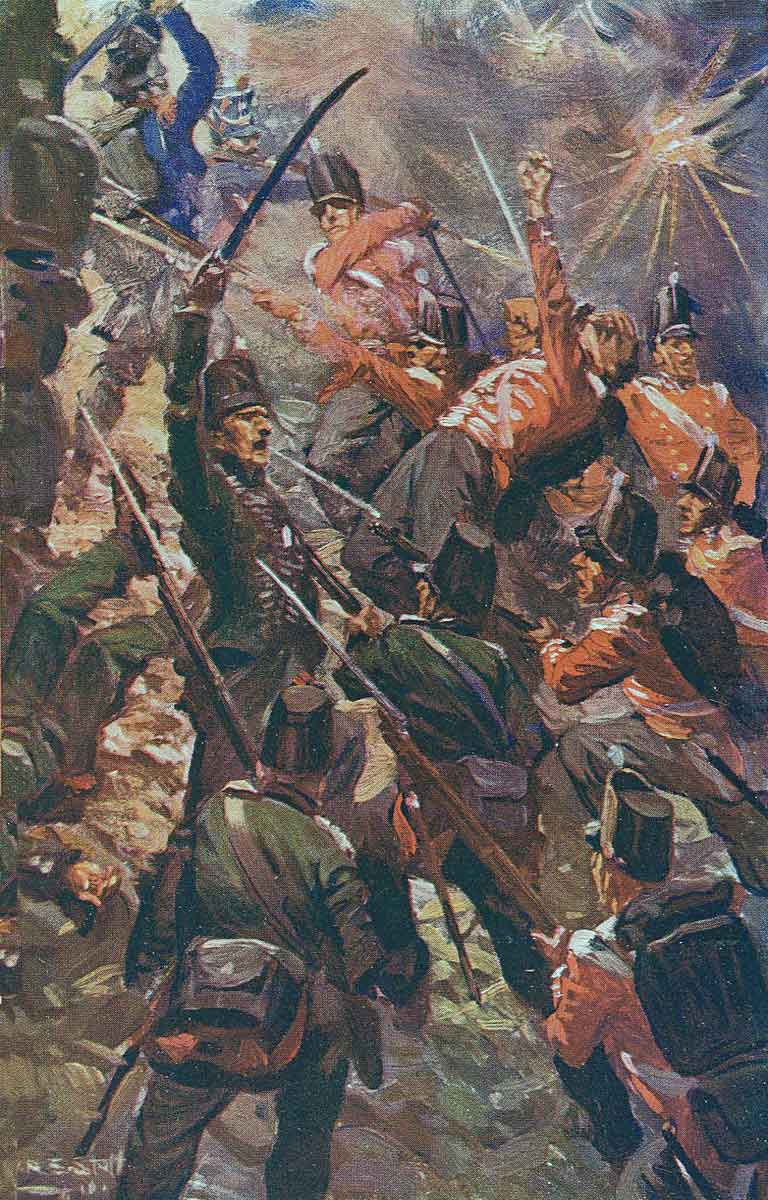

Third Division assault on the Main Breach, during the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War

Throughout the short siege, the heavy and accurate French gunfire made it difficult for the besiegers, destroying much of the siege works as soon as they were built and forcing the besiegers to dig their gun batteries into the ground, rather than place them behind raised earthworks, which were quicker to build but easier to destroy.

The winter climate, with snow across the countryside, added to the difficulties of the besiegers.

The strain of building the siege works under heavy fire and in the extreme cold was addressed by changing the divisions in the siege lines every 24 hours.

Kincaid points out that this was an inefficient system, as so much time was spent marching back and forth from quarters, all several miles away. For the divisions quartered south of the Agueda, the march involved wading across the river and spending much of the duty in freezing wet clothes.

9th January 1812:

On 9th January 1812, the British engineers began the work of building the first 3 batteries for 27 guns.

Wellington’s plan was to have 33 guns firing from the Great Teson and, under their covering barrage, to work forward onto the Lesser Teson and position guns on that feature, using the much shorter range to blast a breach in the city’s defences, through which the assault would be made.

13th January 1812:

On 13th January 1812, Wellington heard that Marshal Marmont was marching from Salamanca to the River Douro and formed the view that Marmont was preparing to relieve Ciudad Rodrigo with the French Army of Portugal and that he had only a few days in which to capture the city.

Wellington was advised by his engineers that a breach, sufficient for a successful attack, could be made in the defences using the guns already in place on the Great Teson, without the need to build further batteries on the Little Teson. Wellington resolved to take this course.

Offices of the French Foot Artillery: Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Suhl

Barrié sent out 3 messengers to Marmont at Salamanca during 9th and 10th January 1812, informing him that Ciudad Rodrigo was under attack by Wellington’s army. All the messengers were intercepted by Spanish guerrillas. It seems likely that none of the senior French commanders, including Marmont, became aware of the attack on Ciudad Rodrigo until 15th January 1812.

The move by Marmont that alarmed Wellington, seems to have been simply in compliance with directions given by the Emperor Napoleon in Paris, not in preparation for a march to relieve Ciudad Rodrigo.

Wellington resolved to begin the digging of the Second Parallel along the summit of the Little Teson.

To enable this work to be carried out, an attack was launched on the French garrison in the Convent of Santa Cruz, lying to the south-west of the Little Teson ridge.

The attack, by 300 men of the 60th Rifles and the King’s German Legion was successfully carried out overnight, with 37 casualties.

27 guns were mounted in the new battery and the Second Parallel driven forward.

14th January 1812:

On 14th January 1812, the French responded to the previous day’s attack by re-capturing the Convent of Santa Cruz with a force of 500 men, enabling them to destroy the new works.

The French were about to attack the new battery, when General Graham’s Third Division arrived and drove them back.

In the afternoon, the newly placed British guns opened fire on the most northern angle of the city defences, the point which would become the ‘Main Breach’.

In the evening, the British 40th Regiment stormed the Convent of San Francisco and went on to occupy the northern suburbs beyond the convent.

Officer of the 52nd Light Infantry: Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War

15th January 1812:

Throughout 15th January 1812, the British guns fired on the ‘Main Breach’, until both the outer and inner walls were heavily damaged.

Fire was then opened on a section of the defences 200 yards east of the Great Breach, to create a second point of attack, to be known as the ‘Lesser Breach’.

Included in the targeting of the Lesser Breach, was a tower in the old fortifications which provided a point of vantage over the length of wall to the Main Breach.

Overnight, 5 more guns were added to the battery.

16th January 1812:

A dense fog settled over Ciudad Rodrigo in the early morning of 16th January 1812, bringing all gun fire to a halt.

The British used the fog cover to extend the Second Parallel and install teams of marksmen in rifle pits covering the Main Breach.

17th January 1812:

The fog lifted at noon on 17th January 1812, allowing a furious cannonade to be unleashed by both sides.

French Light Infantry Drummer: Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Knotel

18th January 1812:

At dawn of 18th January 1812, a new battery on the Great Teson opened fire on the Main Breach and Lesser Breach.

The Tower collapsed ‘like an avalanche’, leaving a substantial gap in the city’s defences.

A gun and howitzer were positioned to fire into the Main Breach to prevent any work on re-trenching the gap.

19th January 1812:

At dawn on 19th January 1812, 30 British guns opened fire on both breaches.

In the afternoon, it was considered that the two breaches were sufficient for an attack to be mounted.

The British guns switched to firing at any point of apparent French strength along the fortifications and preparations were made for the assault, Wellington drawing up his plans from one of the advanced positions.

The duty on the 19th was on the Fourth Division, which manned the siege works.

The Third Division and the Light Division arrived in the trenches, as nightfall approached, to carry out the assault on the city.

The Assault on Ciudad Rodrigo on the night of 19th January 1812:

A diversionary attack was mounted by Pack’s Portuguese Brigade on the San Pelayo Gate in the eastern wall of the city.

The assault on the Main Breach fell to the Third Division, while the Light Division attacked the Lesser Breach.

The 83rd Regiment manned the trenches of the Second Parallel, from where it provided covering fire for the attack, shooting at every Frenchman the soldiers could see.

The first task fell to Colonel O’Toole, who, with the Portuguese 2nd Caçadores and the light company of the 83rd Regiment, crossed the Agueda River from the south and seized 2 French guns that were trained on the entrance to the ditch that the initial storming party would have to pass through.

Soldiers of the French Foot Artillery: Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Suhl

Once this was done, the 5th Regiment, followed by the 77th Regiment, which should have remained in reserve, moved quietly from the Convent of Santa Cruz to the gate into the ditch, which they cut through, the noise masked by the continuous aimless firing of the French troops on the ramparts.

The 5th and 77th Regiments were pressing through the gate, to climb the wall to the ditch, when inexplicably a young officer gave an excited whoop, thereby alerting the French garrison that they were under attack. The French troops immediately rained down hand grenades and shells on the British troops.

The soldiers of the 5th placed their ladders against the wall and scaled it, descending into the ditch and rushing round to the site of the Main Breach.

The 5th and 77th were there joined by the Scots Brigade (Colville’s) under the command of Colonel Campbell which had advanced around the outer ditch.

Campbell advanced into the Main Breach but was only able to make limited progress, due to the small number of men available to him.

Later than intended, the Storming Party of the Third Division advanced into the Main Breach from the parallels on the Great Teson.

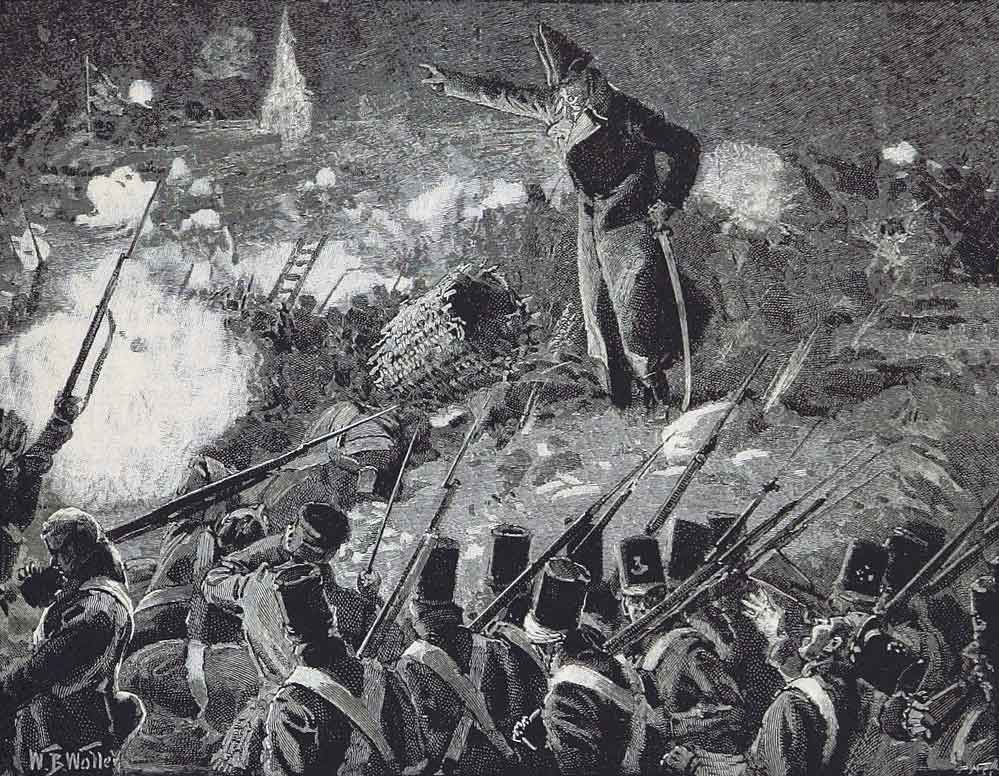

As Colonel Mackinnon led the principal Third Division storming party against the Main Breach, a French magazine exploded hurling many of the attackers into the air. Two well placed French guns opened fire with considerable effect, until the gunners were overwhelmed and the Third Division was enabled to storm through the Main Breach into the city.

Further to the east the Light Division delivered its assault on the Lesser Breach, later than the attack on the Main Breach, as Major George Napier, the commander of the Light Division storming party, was still being briefed by Wellington when the attack on the Main Breach got under way.

The plan was that parties of British sappers and Portuguese Caçadores would carry forward bags of wool and straw to drop into the ditch for the storming party to jump onto.

In the event, the storming party rushed forward at such speed that there was no opportunity for the ditch to be filled in this way, the stormers simply jumping onto the bare earth.

There was some confusion in the attack and it took time for the storming party to identify the direction of the breach, during which, the Light Division stormers suffered significant casualties from the French fire.

General Craufurd directing the Light Division during the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by William Barnes Woollen

Among the casualties were Napier and the commander of the Light Division, Brigadier General Robert Craufurd, shot through the lung.

Some of the Light Division stormers rushed off to the right and were caught up in the magazine explosion that engulfed many of the Third Division stormers.

The main party of the Light Division identified the site of the Lesser Breach and stormed into the city, there being no French re-trenchment in the breach to hold them back.

British stormers from both the Light Division and the Third Division rushed into the city’s cathedral square at about the same time, the French resistance collapsing before them.

The French commander, General Barrié surrendered his sword to Lieutenant Gurwood of the 52nd Light Infantry, leader of the Light Division’s ‘Forlorn Hope’.

British troops proceeded to sack the city of Ciudad Rodrigo, being for the rest of the night beyond the control of their officers. In a French store vats of rum were broken open and consumed, some of the British soldiers being pushed into the vats in the crush and drowned.

Wellington takes down the French flag after the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War

Casualties at the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo:

British and Portuguese casualties during the siege of Ciudad Rodrigo were 533, of which 136 were Portuguese. During the storming British and Portuguese casualties were 105 killed and 394 wounded.

The explosion of the magazine caused around 150 casualties, including Colonel Mackinnon among the dead.

A number of senior British officers were wounded: General Vandeleur, Colonel John Colborne and Major George Napier of the Light Division.

General Robert Craufurd died of his wound on 24th January 1812.

1,800 French troops were captured as a result of the surrender of the garrison. It is not clear what numbers of dead and wounded the French suffered.

Brigadier General Robert Craufurd, mortally wounded during the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War

Brigadier General Robert Craufurd:

General Robert Craufurd died of his wound on 24th January 1812.

The death of Craufurd was a major loss to the British Army.

Craufurd, although only a brigadier general, was the officer to whom Wellington entrusted many important initiatives, particularly those involving the outpost security of the army.

At the beginning of the Peninsular War, Craufurd commanded the Light Brigade, comprising the 43rd and 52nd Light Infantry and the 95th Rifles. Craufurd kept the brigade together by the force of his personality and his fierce discipline during the demanding Corunna campaign.

The success of the brigade caused Wellington to expand the formation to a division by attaching regiments of Portuguese Caçadores.

Craufurd was not popular with his brother officers but was very well thought of by the rank and file of the Light Division, particularly for his impetuous acts of kindness. Craufurd carried a brandy flask and doled out measures to soldiers during the terrible retreat in January 1809.

Craufurd’s skill and experience in conducting outpost operations proved a great asset to Wellington, who permitted him to act with the most cursory of instructions.

Craufurd was inspired by battle and possessed great stamina, remaining in the saddle for long periods during operations.

His loss was mourned by the soldiers of his regiments, particularly the troopers of the 1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion, with whom he had a close working relationship, assisted by his fluency in German.

Follow-up to the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo:

Marshal Marmont received the first report of the siege of the French garrison in Ciudad Rodrigo on 15th January 1812. He immediately ordered a concentration of his troops at Medina del Campo and Salamanca, summoning back the reinforcements sent to Suchet in Valencia and calling up the Young Guard.

Marmont reckoned on having 32,000 men facing Wellington on the Agueda River by 26th or 27th January 1812. As Ciudad Rodrigo was stormed on 19th January 1812, this was too late.

Marmont was stunned to hear that Wellington had taken Ciudad Rodrigo, commenting ‘Never was an operation pushed forward with the like activity.’

Not only was his forward base for the projected re-invasion of Portugal lost to him, but also lost was the French siege train, essential for the project.

While Wellington took the steps necessary to ensure Ciudad Rodrigo was safe from a French counter-stroke, filling in the British siege works, his assessment was that Marmont would not move, once he heard of the capture of the city.

Wellington was correct. Marmont cancelled the intended urgent French advance.

However, Marmont did not disperse the French concentration until the end of the month, waiting to see if Wellington intended an advance into Spain, following the capture of Ciudad Rodrigo, which he did not.

The impact on the French army in Spain of the enforced concentration to relieve Ciudad Rodrigo was substantial. In complying with Marmont’s orders to concentrate, the various French divisions were compelled to carry out forced marches over considerable distances with insufficient supplies, causing casualties and a general drain on the efficiency of the troops.

The absence of the French forces encouraged the Spanish guerrilla bands and enabled them to re-establish control in a number of areas.

In several significant ways, Wellington’s capture of Ciudad Rodrigo was a major disaster for the French.

‘Forlorn Hope’ Medal and GSM awarded to James Morris of the 52nd: Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War

Battle Honours and Medal for the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo:

The Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo is a clasp on the 1848 Military General Service Medal and a battle honour for the following British regiments: 5th, 7th Royal Fusiliers, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 24th, 40th, 42nd Black Watch, 43rd Light Infantry, 45th, 48th, 52nd Light Infantry, 60th Rifles, 74th, 77th, 83rd, 88th Connaught Rangers, 94th and 95th Rifles.

Military General Service Medal with clasp for the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo:

- The French commander of Ciudad Rodrigo seems to have been surprised by the assault on the evening of 19th January 1812. The defenders failed to ensure that the Lesser Breach was defended by a re-trenchment, only attempting to block the gap with a cannon placed sideways. An officer of the British 5th Regiment, captured early in the attack, was told by the French commander, General Barrié, that he had prepared his plan to counter the attack during the morning. Fortescue discounts this and expresses the view that Barrié was unprepared for the assault.

- The British lacked expertise in conducting sieges. The engineer staff had been recently established and lacked experience. The French, on the other hand, had conducted and resisted many sieges across Europe during the 18th Century and the early years of the 19th Century. The main textbook on the subject was in French.

- Fortescue relates that the British artillery was concentrated on blasting the two breaches in the walls, rather than countering the French cannon and musket fire from the fortifications. This led to greater levels of British and Portuguese casualties, although enabling the assault to be made more quickly.

- The officers of the 52nd Light Infantry, in 1820, instituted a ‘Forlorn Hope’ medal, awarded to the survivors of the regimental forlorn hope parties in the storming of Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz and San Sebastian. The medal replaced a laurel badge worn on the right arm with the initials ‘VS’ for Valiant Stormer.

French illustration of the Assault on the Breach at the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 in the Peninsular War

References for the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of Arroyo Molinos

The next battle in the Peninsular War is the Storming of Badajoz

26. Podcast of the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo: The sudden capture by Wellington on 19th January 1812 of Marmont’s ‘base of operations’ for the intended third French invasion of Portugal during the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts