Wellington’s hard-fought capture, on 6th April 1812, of the second French base on the Portuguese border, the southern gateway for the British invasion of Spain, during the Peninsular War

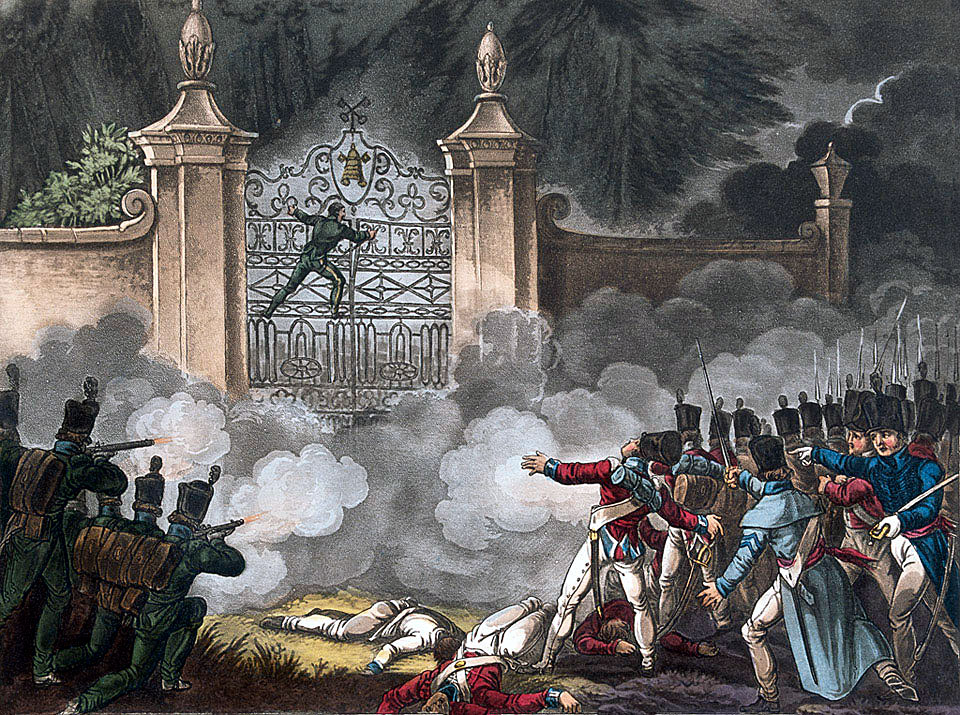

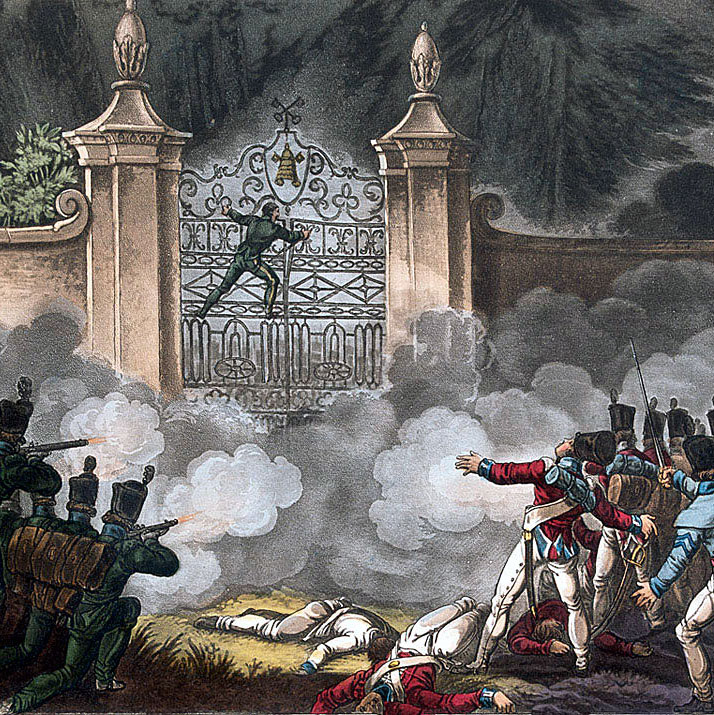

Attacking the Bishop’s Palace during the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

27. Podcast of the Storming of Badajoz: Wellington’s capture, on 6th April 1812, of the second French base on the Portuguese border, the southern gateway for the British invasion of Spain, during the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

27. Podcast of the Storming of Badajoz: Wellington’s capture, on 6th April 1812, of the second French base on the Portuguese border, the southern gateway for the British invasion of Spain, during the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Peninsular War is the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo

The next battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of Villagarcia

Battle: Storming of Badajoz

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Storming of Badajoz: 6th April 1812

Place of the Storming of Badajoz: In South-Western Spain, near the Portuguese border.

Combatants at the Storming of Badajoz: British and Portuguese troops against the French.

General Armand Philippon, French commander at the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

Commanders at the Storming of Badajoz: The commander of the British and Portuguese force was Lord Wellington.

The French governor of Badajoz was General Philippon, an officer with a reputation for resourcefulness and courage, fully borne out by his conduct of the defence of Badajoz.

Size of the armies at the Storming of Badajoz:

The formations in the assault were the Third, Fourth, Fifth and Light Divisions of Wellington’s army, around 25,000 men.

The French records show the garrison as numbering around 4,000 men. The French were well equipped with artillery.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Storming of Badajoz:

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers and shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments, the 60th and 95th, wore dark green jackets and trousers.

Highland troops wore the kilt and feather bonnets.

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light cavalry wore light blue tunics with characteristic leather helmets covered by a bearskin crest.

Wellington after the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

The Portuguese army uniforms during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue. Most infantry wore a shako headdress.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry. The horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket, that could be fired three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for around a hundred metres. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, fitting into the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, with a sword bayonet.

General James Leith, commander of the Fifth Division at the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who developed it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was not able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create a powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns, with the speed of French infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

Winner of the Storming of Badajoz:

On 6th April 1812, the British and Portuguese troops stormed the fortified city of Badajoz, albeit with heavy casualties, the French garrison surrendering.

Badajoz during the unsuccessful British siege in June 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Thomas Staunton St Clair

Background to the Storming of Badajoz:

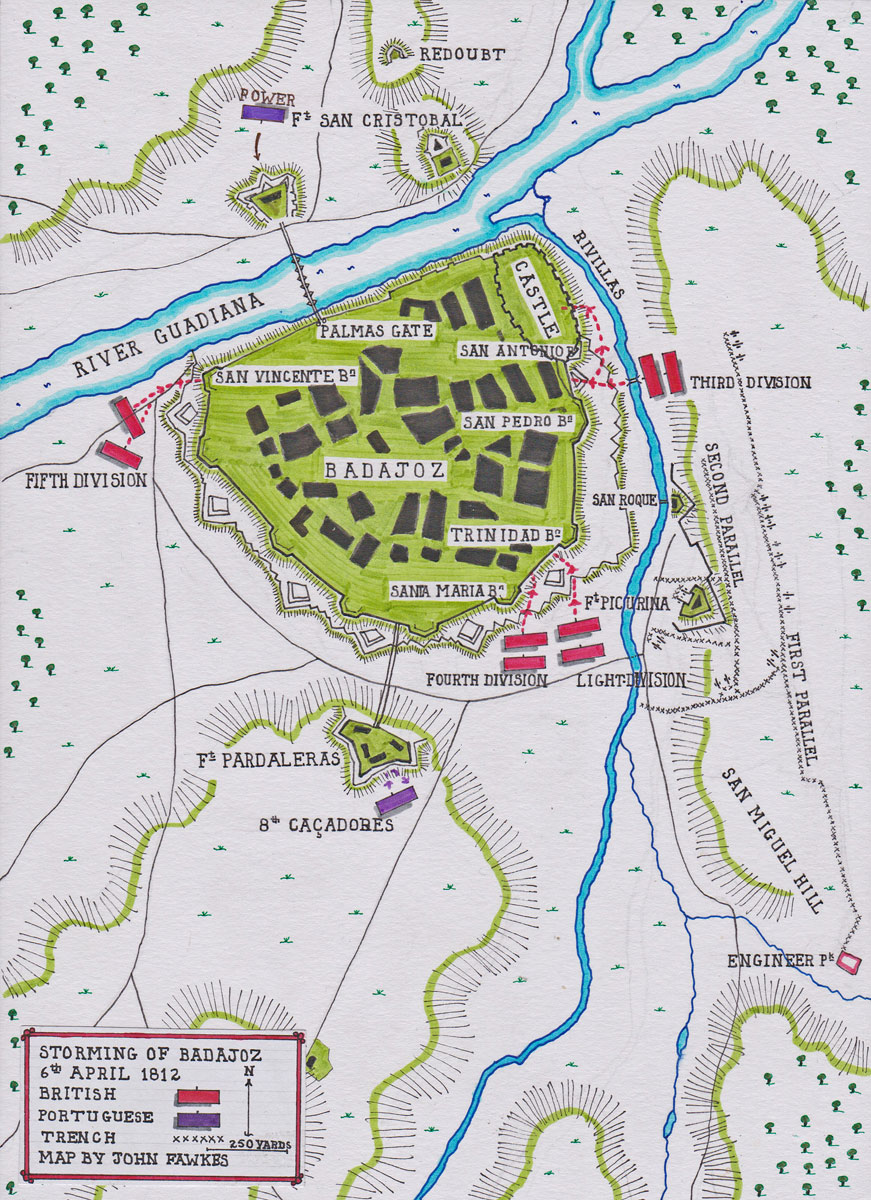

The city of Badajoz stands on the south bank of the Guadiana River, within 10 miles of the Portuguese border and was, with the city of Ciudad Rodrigo, one of the keys to an invasion from Portugal into Spain by Lord Wellington’s British and Portuguese army.

Wellington needed to take both cities, before he could launch his invasion into Spain.

Wellington captured Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812. He thereupon turned his attention to the southern city, Badajoz.

The broad strategic position of the French forces in Spain was that King Joseph, brother to the Emperor Napoleon, held Madrid and Castile.

Following the unsuccessful French invasion of Portugal in 1811, the French ‘Army of Portugal’, now commanded by Marshal Marmont in succession to Marshal Massena, lay in the north-west provinces of Spain.

The French ‘Army of the South’, commanded by Marshal Soult, held much of southern Spanish, where he struggled to establish and hold what Soult considered to be his personal fiefdom.

45th Regiment in the Third Division attack during the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

A number of features complicated the French operations in Spain: the various French marshals were bitter personal rivals and reluctant to assist each other: the hatred the Spanish bore the occupying French was such that the French found it difficult to gather information or supplies or even move about other than in large units: the Emperor Napoleon attempted to control operations in Spain from Paris; by the time his orders reached his marshals in Spain they were often no longer appropriate to the circumstances: in 1812, Napoleon began withdrawing from Spain key units, such as the Imperial Guard and Polish regiments, for his projected invasion of Russia.

Badajoz fell within the area of the French Army of the South. It was Marshal Soult’s responsibility to hold the city. However, Soult’s commitments were such that he could not relieve Badajoz in the event of a British attack, without the assistance of Marshal Marmont’s Army of Portugal, positioned further north.

At the end of January 1812, Wellington concluded that Marshal Marmont would not move against Ciudad Rodrigo and that he could move his army south to besiege and capture Badajoz.

Wellington directed that supplies be brought from the British depot on the Atlantic coast at Setubal, the estuary immediately to the south of Lisbon, to his base at Elvas, the Portuguese town 10 miles to the west of Badajoz.

On 28th January 1812, the weather changed from frost to heavy rain, immediately impeding all movement.

On 31st January 1812, the British troops returned from the area of Ciudad Rodrigo to their cantonments along the Portuguese border and, on hearing of this move, Marmont dispersed his assembled divisions.

Marshal Soult, in the far south of Spain, supervising the siege of the Spanish garrison in Cadiz, heard of the British capture of Ciudad Rodrigo on 31st January 1812 and concluded that Wellington’s next operation would be the capture of Badajoz, a prospect that threatened his own position.

27. Podcast of the Storming of Badajoz: Wellington’s capture, on 6th April 1812, of the second French base on the Portuguese border, the southern gateway for the British invasion of Spain, during the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

27. Podcast of the Storming of Badajoz: Wellington’s capture, on 6th April 1812, of the second French base on the Portuguese border, the southern gateway for the British invasion of Spain, during the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

A week later, Soult heard of the gathering of supplies by the British in the frontier town of Elvas.

On 9th February 1812, Soult wrote to Marmont, seeking his help for the relief of Badajoz and began his own preparations.

Soult’s subordinate, General D’Erlon, advanced to Medellin, on the Guadiana River, 50 miles to the east of Badajoz, but with a force of insufficient strength to interfere with any serious attack on Badajoz.

Other French formations occupied the areas under Soult’s command in Andalusia and Murcia.

At the same time, orders arrived from Paris requiring the dispatch of some 7,000 men to join the assembling Grand Army in Eastern Prussia,

Soult was compelled to appeal to Marmont for assistance in preventing the loss of Badajoz.

British 74th Regiment, Third Division, in the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

On hearing of the fall of Ciudad Rodrigo, the Emperor Napoleon wrote a series of enraged letters from Paris blaming the French commanders in Western Spain for the loss of the city. He also gave detailed instructions for the disposition of the French forces.

Napoleon based his directions on the supposition that Wellington did not have the strength to attack Badajoz, which was what Wellington was intending to do.

Napoleon was by now primarily concerned with his plans for the invasion of Russia, arranging affairs in Spain to enable more French troops to be available.

On 18th February 1812, Napoleon ordered the whole of the Imperial Guard in Spain to march for France within 24 hours.

In addition, Marmont and Soult were having great difficulty assembling sufficient supplies to support a heavy concentration of troops, making an attempt to relieve the French garrison of Badajoz problematic.

On the British side, Wellington was bringing forward his arrangements for the attack on Badajoz.

Wellington’s information on the French dispositions was sufficiently accurate to enable him to permit his army to disperse for the march south without fear of French interference.

The heavy guns used against Ciudad Rodrigo could not be moved south, due to the lack of draught oxen in sufficient health for the journey.

Major Dickson of the Royal Artillery was entrusted with assembling a new siege train. Dickson encountered considerable difficulty in obtaining appropriate heavy guns from the Royal Navy, the nearest source for such weapons.

Finally, on 30th January 1812, Dickson’s siege train began the journey from the Portuguese coast to Elvas, with guns from the Navy and twenty 24 pounders sent from England.

On 16th February 1812, Wellington’s regiments began the journey south from their cantonments west of Ciudad Rodrigo.

The British divisions took different routes, to collect new clothing and footwear brought up by river from the coastal depots.

Wellington remained with his headquarters at Freineda in Portugal, to the west of Ciudad Rodrigo, to deceive the French as to his intentions, finally leaving for the attack on Badajoz on 6th March 1812.

Wellington’s headquarters in Freineda, Portugal: Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

Marmont was, however, aware of the movement south of the British troops and began his deployment towards Badajoz.

On 22nd February 1812, Soult, acting on information from D’Erlon on the Guadiana River, formed the view that Wellington had abandoned his plans to attack Badajoz and dispatched the troops to France ordered by the Emperor.

On 5th March 1812, Soult received information from General Philippon, the French garrison commander in Badajoz and from D’Erlon that the British build up at Elvas had resumed, clearly there was to be a British attack on Badajoz.

Soult wrote to the Emperor’s chief of staff, Marshal Berthier, that unless his troops currently in the interior of Spain and 25,000 men from the Army of Portugal were sent to him he could not be responsible for the impending loss of Badajoz.

There was no satisfactory reply to Soult’s demands.

Wellington resolved to begin the siege of Badajoz on 16th March 1812, even though the build-up of supplies at Elvas was not complete and some British regiments were still on the march from the north.

On 15th March 1812, two bridges were erected over the Guadiana River, one 10 miles to the west of Badajoz and the other just above the city, to the east.

British Fifth Division escalading the San Vincente bastion in the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

On 16th March 1812, General Graham took the British First, Sixth and Seventh Divisions to the south-east of Badajoz to prevent Soult or D’Erlon from interfering with the siege operation.

The British Third and Fourth Divisions encamped on the heights to the south of Badajoz, where they were joined on 17th March 1812 by the Light Division.

To the north of the Guadiana River, General Hill took two further divisions and the British and Portuguese cavalry to the east of Badajoz, to keep a watch on Marmont’s troops, although, acting reluctantly on the Emperor’s orders, Marmont was compelled to withdraw most of his troops further north, making any attempt to relieve Badajoz impossible.

In the south, Soult could not attempt the relief of Badajoz without leaving Andalusia stripped of French troops and open to invasion by the Spanish General Ballesteros.

The siege of Badajoz:

The three British divisions about to launch the attack on Badajoz, the Third, Fourth and Light Divisions, comprised some 11,000 men.

On 17th March 1812, the British conducted a survey of the defences of Badajoz.

Considerable improvements to the fortifications had been made since the abandoned British siege of Badajoz in May and June 1811.

The fort of San Christobal on the north bank of the Guadiana River had been strengthened and a redoubt built on the neighbouring hill, the site of the British breaching battery in 1811.

Pardaleras, the fort to the south of the city’s perimeter, had been strengthened and connected with the main city fortifications.

The breach blown in the castle wall at the north-eastern corner of the city during the 1811 attack had been repaired and was now a fortification, housing a number of guns.

On the eastern side of Badajoz, the Rivillas Stream had been dammed to create an impassable inundation.

British siege works for the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Philippoteaux

On the hillside of San Miguel, to the east of the city, stood the lunette of San Roque, covering the Rivillas dam and to the south-east of the city and the substantial Fort Picurina.

On the western side of the city, the French had built three ravelins or triangular earth fortifications, with explosive mines buried in the ground in front of them.

140 pieces of cannon were mounted along the walls and the garrison comprised some 5,000 troops of all arms.

Due to the success of General Hill in preventing convoys from reaching the French garrison of Badajoz, there was an insufficiency of ammunition in the city for the substantial force of artillery.

There were adequate supplies of food for the garrison, to last 6 or 7 weeks.

Soon after the arrival of the British divisions before Badajoz, a warrant officer of the French engineers deserted to the British, with a set of the plans for the mines laid in front of the new fortifications on the west side of the city.

Wellington’s army was hampered by the absence in the British army of a corps of trained sappers and miners, an essential component in all European armies for conducting or resisting sieges.

This inadequacy and the threat of a relief attack by Soult or Massena excluded a conventional siege. The British, as at Ciudad Rodrigo, would simply blast breaches in the defences and storm them.

The result would inevitably be heavy casualties for the attacking army.

Preliminary operations before the Storming of Badajoz:

Wellington considered that he did not have the resources to attack the western side of the city and that the castle was too strong to attempt to escalade its walls.

The only possible point of attack was the south-eastern corner, with batteries mounted on the neighbouring San Miguel Hill to blast a breach in the defences.

The first major step would be to capture the Picurina Fort which stood on the western end of San Miguel Hill.

The British engineer park was positioned behind the San Miguel Hill and, on the night of 17th January 1812, a communication trench was begun to the planned site of the First Parallel encircling the Picurina Fort.

The next morning, the garrison of Fort Picurina and the guns on the city’s fortifications opened a furious bombardment on the British works.

Lieutenant Colonel Macleod leading the 43rd Light Infantry in the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by John Augustus Atkinson

In the evening of 18th January 1812, the position of two batteries was laid out, one facing each of the forward sides of the fort.

In the early afternoon of 19th January 1812, under cover of fog, 1,100 men of the French garrison launched a surprise attack on the British troops working on the right of the First Parallel while another party attacked the left.

A party of French cavalry rode round the hill and attacked the engineer park.

After initial success, the British troops were rallied and drove the French troops back into the fortifications.

French casualties were around 180 killed and wounded, the French carrying off a large number of tools.

British casualties were around 150 killed and wounded, with the chief engineer, Colonel Fletcher wounded in the attack, but continuing to supervise the siege works from his bed.

From then on, a squadron of British cavalry and a battery of field guns were maintained behind the San Miguel hill in case of any further French attack.

The British parallel was dug beyond the San Roque redoubt and additional batteries installed to batter the city’s defences. The work was hampered by heavy rain.

On 22nd March 1812, the French countered the work on the First Parallel by installing 3 field guns on the north bank of the Guadiana River, firing into the flank of the British works and causing extensive damage.

Wellington ordered the Fifth Division to advance from Campo Maior and occupy the north bank of the Guadiana, thereby displacing the 3 French field guns.

In the afternoon a heavy rain fell which flooded the British entrenchments and washed away the pontoon bridge over the Guadiana River.

On 24th March 1812, the weather cleared up, enabling the British to complete the six batteries, install 28 heavy guns and, the next day, to open fire on the San Roque lunette, Fort Picurina and the site of the intended breach in the main city fortifications, between the Trinidad and Santa Maria bastions.

In spite of a heavy fire from the guns on the city’s fortifications, the guns in Picurina were quickly silenced and the works damaged.

The French prepared to defend against the assault on Fort Picurina, which was clearly impending.

The capture of Fort Picurina:

The British attack on Fort Picurina was delivered at around 9pm on 25th March 1812.

Parties assaulted each flank of the fort but were unable to gain access.

However, the French attention was diverted to these points of danger and General Kempt, commanding in the trenches, launched his reserve against the central angle of the fort’s defences.

This force quickly forced its way onto the parapet and drove the French troops back.

A British force, waiting to the rear of the fort, intercepted a French column, advancing from the city to assist the Picurina garrison and drove it back to the city fortifications.

A party from the Light Division battered down the main gate with axes and, after 45 minutes of fighting, Fort Picurina was taken. Of the fort’s garrison of 230 officers and men, 1 officer and 31 men escaped to the city. The remainder were killed or captured.

Of the British storming party, around 600 men mainly from the Third Division, 319 officers and men were killed or wounded. Few officers were left standing after the fight.

The French commandant of Badajoz, General Philippon, considered the Fort Picurina garrison to have behaved badly and that the British assault should have been repelled. The various mines, shells and powder barrels deployed for use against an assault were not exploded. Philippon issued a general order expressing this view.

88th Connaught Rangers attacking the Castle at the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

The Breach in the Badajoz fortifications:

British batteries were now established to fire more directly on the Trinidad and Santa Maria bastions and the entrenchments to their front and between them.

The British dug a Second Parallel along the face of the San Roque lunette, which protected the dam on the Rivillas Stream.

It was now clear to Philippon that the main British attack would fall on the south-east corner of the city, where the Trinidad and Santa Maria bastions stood and he re-doubled his efforts to improve the defences there.

French sharp shooters took up positions in sandbagged emplacements to pick off the British troops working in the advanced trenches and firing the siege guns.

French attempts to relieve Badajoz:

On 23rd March 1812, Soult launched an attempt to relieve Badajoz, marching north with around 21,000 men, the largest force he could raise without leaving Andalusia and the siege of Cadiz dangerously denuded.

Wellington ordered Hill to withdraw to Merida to cover the north side of the Guadiana River and moved the Fifth Division to support Graham to the south-east of the city, replacing it outside Badajoz by a Portuguese brigade.

To the north, Marmont managed to assemble supplies for an advance and a number of large guns, with the intention of threatening Ciudad Rodrigo and thereby compel Wellington to abandon the attack on Badajoz and come to the assistance of the Spanish garrison.

Nevertheless, Wellington proceeded with the attack on Badajoz without pause.

Light Division jumping into the ditch at the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

Preparations for the British assault on Badajoz:

Between 30th March and 5th April 1812, 38 British guns bombarded the French defences in the south-eastern corner of Badajoz.

While initially the British assault was set for the evening of 5th April 1812, it was deferred for a day to inflict more damage on the breach, with 14 heavy howitzers brought up to add to the firepower.

Wellington felt pressed for time as Soult had reached Llerena, some seventy miles from Badajoz.

Plans were put in place to give battle to Soult at Albuera, in the event that he came too close before Badajoz could be captured.

The time for the assault on the city was finally set for 10pm on 6th April 1812.

In the context of conventional European siege warfare, the assault was premature. More bombardment should have been carried out on the Main Breach, to level the earth ramparts the French had built on each side of the ditch.

The French garrison under Philippon had prepared additional defences. Retrenchments had been dug across the breaches between the Trinidad and Santa Maria bastions and the San Pedro and San Antonio bastions on the eastern fortification adjacent to the castle.

The French had also dug a further ditch along the base of the outer rampart, increasing its height. The ditch had, without the British observing, been flooded so that the attacking parties faced an unexpected moat in the fortifications.

The French had, so far as possible, kept the breaches clear of rubble.

A French battery had been erected overlooking the Great Breach.

Where the parapet had collapsed under the bombardment, it had been replaced with sacks of wool or sand. The slope of the breach was covered with planks studded with spikes. Chevaux de frises made of sword blades welded together were ready to be deployed in front of the defences when the attack was delivered.

A row of mines had been dug beneath the Main Breach to be exploded under the attacking party. Barrels of gunpowder were ready to roll down the slope and explode.

Around a quarter of the garrison were allocated to the area of the expected attack, each man provided with several muskets, to enable him to maintain a continuous fire.

Picton’s Third Division capturing the Castle during the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by R. Westall

The plan for the assault on Badajoz:

Picton’s Third Division was to attack the castle in the north-east corner of the city.

The Fourth Division and the Light Division were to attack the Main Breach between La Trinidad and Santa Maria bastions, the Fourth turning to attack La Trinidad and the Light the Santa Maria.

General Leith’s Fifth Division was to make a feint attack on Pardaleras, followed by a genuine attack on the San Vincente bastion in the north-west corner of the city.

Major Wilson of the 48th Regiment was to lead the trench guards in an attack on the San Roque lunette.

General Power’s Portuguese were to make a diversionary attack on the bridge-head on the north bank of the Guadiana River.

Each attacking column was led by a ‘forlorn hope’ of an officer and around 50 men, all volunteers, few of whom could expect to survive the assault.

‘Forlorn Hope’ at the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Vereker Hamilton

The final British assault on Badajoz:

At 8pm on 6th April 1812, the British and Portuguese troops assembled for the assault.

The night was dark and misty. The guns were silent.

Napier describes the British troops as looking like savages, brown unshaven faces, in battered uniforms, trousers rolled up and tunics loosened.

As the columns from the Fourth and Light Divisions prepared to advance, at 9.30pm, the first attack went in.

The trench guards opened fire on the San Roque lunette, while a party made its way around the back of the work and stormed in. The French were taken by surprise and San Roque quickly captured.

The British immediately set to work to destroy the dam on the Rivillas Stream and release the inundation. This was not completed in time to assist the other assaults.

Soon afterwards, Picton’s leading brigade reached the Rivillas Stream and the advanced party of the 60th Regiment crossed the dam, where they came under fire.

The French opened a general fire on Picton’s men, who crossed the narrow dam with considerable difficulty and suffered many casualties. Picton himself was wounded.

Once across the dam, the Third Division men attempted to scale the wall between the San Pedro and San Antonio bastions. The British troops were subjected to a devastating cross-fire from the two bastions, with explosive devices thrown down on them by the French lining the parapet above them.

After 45 minutes the Third Division troops fell back and took cover.

Sir Thomas Picton leads the Third Division in capturing the Castle during the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by J,J.Jenkins

Officer of the 83rd Regiment: Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

The attack by the Fourth and Light Divisions:

At around 10pm on 6th April 1812, the Fourth and Light Divisions advanced to the edge of the main ditch and climbed down into it, using ladders.

All firing had ceased in the area, the French holding their fire.

Once the ditch was full of British troops, the French detonated a line of shells buried along the ditch bottom. The resulting explosion killed or wounded most of the Light Division storming party and many of the Fourth Division party.

The French expectation was that this blow would end the attack.

In fact, the following columns from the two divisions pressed forward to take the places of their fallen comrades.

The British troops jumped or scrambled down into the ditch, which was much deeper than expected and flooded. Many of the troops were drowned.

Due to the darkness and confusion of battle, the attacking columns mistook a different section of the fortifications for the breach and swarmed over it to meet a heavy fire.

Repeated rushes were made up the steep slope to be met by devastating volleys or stopped by the various obstacles erected by the French garrison.

The attack was resumed several times, once on the arrival of the Portuguese Reserve, until almost all the officers and many of the soldiers were casualties.

At this point, some two hours after the onset of the attack, the recall was sounded and the remnants of the two divisions fell back to the quarry where they had assembled.

83rd Regiment attacking the Castle in the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

The attack on the Castle:

After the initial failure of the Third Division attack, General Picton, once he had recovered from the shock of his wound, led a further assault with his second brigade.

This time the Third Division assault was against the walls of the Castle.

General Thomas Picton, commander of the British Third Division at the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

The 5th (Northumberland) Regiment led the attack, placing its ladders against a section of the wall that had been breached in the 1811 siege and, although repaired, was lower than the rest of the wall.

Major Ridge, the commanding officer of the 5th, led his regiment’s grenadiers up onto the parapet and found the French unprepared for the attack.

The 5th drove the French they encountered out of the castle but were halted at the outer gate which the French barricaded and defended vigorously.

Medal commemorating the capture of the Castle by General Picton in the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

Picton withdrew his men to the inner gate and awaited events.

The French 88th Regiment of the Line, ordered by Philippon to re-take the Castle, marched up to the inner gate and a voice demanded entry in English.

Not fooled by this ploy, Picton admitted the French troops, but subjected them to a volley and charge, driving them back through the outer gate. Again, the British troops were unable to penetrate the gate and gain access to the city.

Picton abandoned his attempts to pass the outer gate and sent word to Wellington of his division’s success.

Wellington received the news of Picton’s capture of the Castle immediately after the reports from the Fourth and Light Divisions of the failure of their attacks on the Main Breach.

Fifth Division scaling the San Vincente Bastion during the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

The Fifth Division’s attack on the San Vincente bastion:

The feint attack on Fort Pardeleras was carried out by the Portuguese 8th Caçadores.

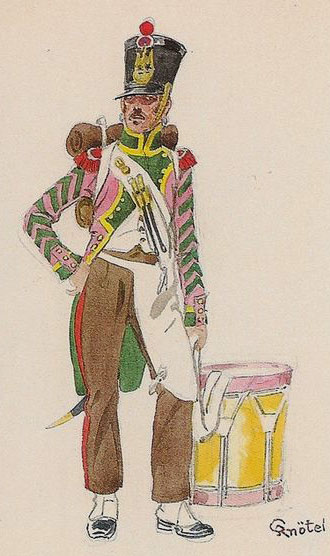

Grenadier Drummer of the French 88th of the Line: Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Knotel

The ladders for the Fifth Division’s attack were delayed and the division was not in place to deliver its attack on the San Vincente bastion in the north-west corner of the Badajoz fortifications until midnight, the time at which the main attack by the Third and Light Divisions was being abandoned.

Walker’s brigade of the Fifth Division, with 3 battalions, headed the attack.

In spite of there having been no preparatory artillery bombardment, Walker’s brigade (4th, 30th and 44th regiments, headed by their light companies) stormed the defences against a heavy direct and flanking fire. They were immediately followed by the 38th and 44th Regiments.

French sources stated that a large proportion of the garrison of that part of the defences, amounting to 2 companies of infantry, were sent to recover the Castle, leaving the San Vincente Bastion seriously undermanned.

As the attack went in, it was found that the ladders were too short to reach the top of the wall, forcing the troops to scramble up to the parapet.

One embrasure was found to be unmanned, enabling Walker’s men to enter.

Once over the wall, the 4th King’s Own Regiment attempted, unsuccessfully, to force its way into the city, while the rest of Walker’s brigade advanced along the ramparts, capturing three bastions. In the third bastion, General Walker was seriously wounded.

French garrison surrenders after the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

From there the French drove the brigade along the ramparts back to the San Vincente bastion, where they were met by the second brigade of the Fifth Division.

The British 38th Regiment destroyed the French assault with a single concerted volley.

The whole of the Fifth Division then advanced around the town towards the Main Breach with its bugles blaring the advance.

The bugle calls were met by calls from Picton’s men in the castle, at which French resistance collapsed, the garrison of the Main Breach breaking their arms and surrendering to the now advancing Fourth and Light Divisions.

General Philippon crossed the river to the bridgehead, from where he despatched his small force of cavalry to Marshal Soult to inform him of the fall of Badajoz and then surrendered to Lord Fitzroy Somerset.

British troops looting after the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

Army Gold Medal awarded to Lord Fitzroy Somerset for bravery at the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War

Aftermath to the Capture of Badajoz:

Following the capture of Badajoz, the British and Portuguese troops indulged in three days of looting the city, before order could be restored.

As in the rioting following the capture of Ciudad Rodrigo, a number of British soldiers feel into vats of drink and were drowned.

Finally, a gallows was erected in the city centre and several British soldiers were hanged.

Thereafter order was slowly restored in the British and Portuguese regiments.

Receiving Philippon’s report of the fall of Badajoz, Soult withdrew to the south.

Wellington marched his army north, where Massena abandoned his threat to Ciudad Rodrigo, before moving into Spain and fighting the decisive Battle of Salamanca.

Military General Service Medal with clasp for the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: awarded to Private J. Jeane of 4th King’s Own Regiment

Battle Honours and Medal for the Storming of Badajoz:

The Storming of Badajoz is a clasp on the 1848 Military General Service Medal and a battle honour for the following British regiments: 4th King’s Own, 5th, 7th Royal Fusiliers, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 27th, 30th, 38th, 40th, 43rd Light Infantry, 44th, 45th, 51st, 52nd Light Infantry, 60th Rifles, 74th, 77th, 83rd, 88th Connaught Rangers, 92nd, 94th, 97th and 95th Rifles.

Casualties at the Storming of Badajoz:

Three quarters of the British and Portuguese assaulting parties became casualties in the attack, with 4,000 British killed and wounded and 1,000 Portuguese killed and wounded.

6 generals were wounded: Picton, Walker, Colville, Kempt, Bowes and Harvey.

4 battalion commanders were killed: Ridge of the 5th, Grey of the 30th, McLeod of the 43rd Light Infantry and O’Hare of the 95th Rifles.

In the Light Division, the 43rd suffered 347 casualties, the 52nd suffered 323 casualties and the 95th Rifles suffered 258 casualties. Each of these battalions comprised around 950 all ranks before the attack.

In the Fifth Division the 4th King’s Own Regiment suffered 230 casualties from 530 all ranks.

The whole French garrison of around 4,000 men was killed or captured, other than the small party of cavalry sent out by Philippon after the city had been lost.

In the British attack on the Main Breach, it is said that not more than 20 French soldiers became casualties.

British regiments at the Storming of Badajoz with casualties (killed and wounded):

Royal Artillery: 2 officers and 20 soldiers

Royal Engineers: 5 officers and 5 soldiers

Light Division

43rd Light Infantry: 18 officers and 329 soldiers

52nd Light Infantry: 18 officers and 305 soldiers

1st/95th Rifles: 14 officers and 179 soldiers

3rd/95th Rifles: 8 officers and 56 soldiers

Officer of the 30th Regiment: Storming the San Vincente Bastion in the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Third Division

5th: 4 officers and 41 soldiers

45th: 14 officers and 83 soldiers

74th: 7 officers and 47 soldiers

77th: 3 officers and 10 soldiers

83rd: 8 officers and 62 soldiers

88th: 10 officers and 135 soldiers

94th: 2 officers and 154 soldiers

Fourth Division

7th: 17 officers and 153 soldiers

23rd: 17 officers and 134 soldiers

27th: 15 officers and 170 soldiers

40th: 16 officers and 124 soldiers

48th: 19 officers and 154 soldiers

Fifth Division

1st: 2 officers (this battalion was acting as the commander-in-chief’s escort)

4th: 17 officers and 213 soldiers

30th: 6 officers and 126 soldiers

9th: no casualties

38th: 5 officers and 37 soldiers

44th: 9 officers and 95 soldiers

Divisional troops:

60th: 4 officers and 30 soldiers

Brunswick Oels: 2 officers and 30 soldiers

Escalade of the San Vincente Bastion by 2nd/30th Regiment at the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Anecdotes and traditions from the Storming of Badajoz:

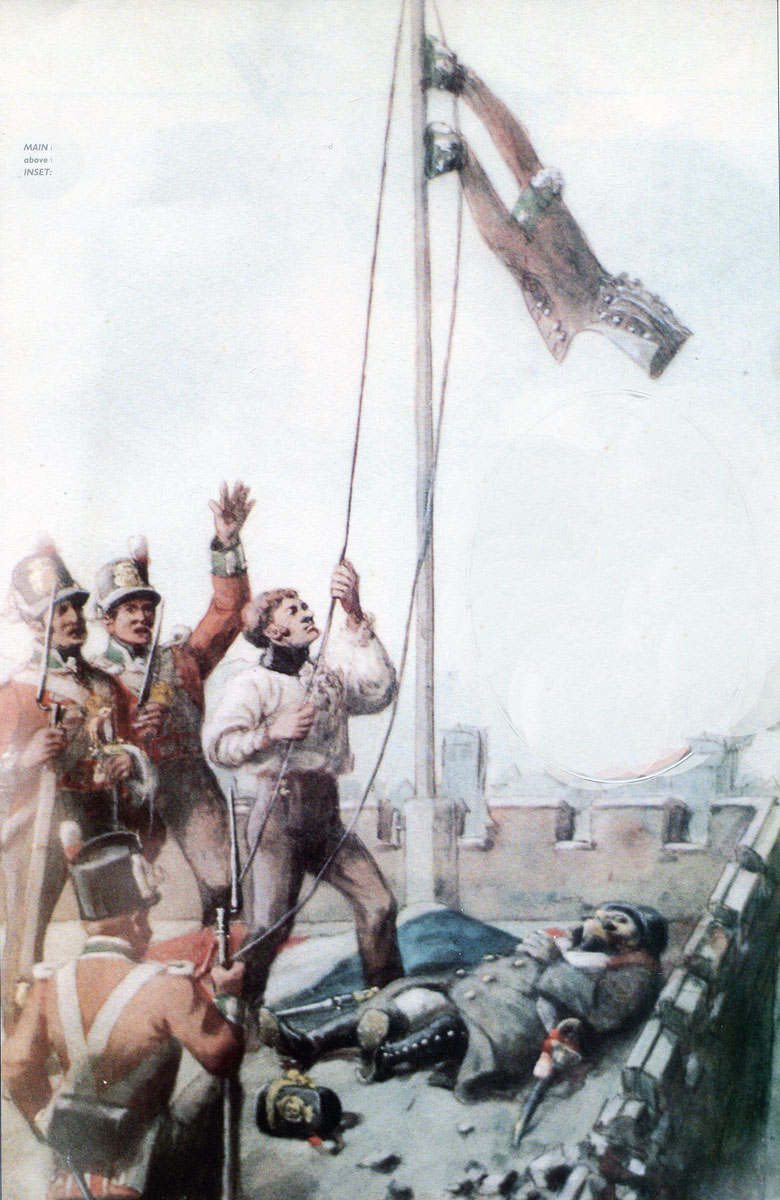

Lieutenant Macpherson of the 45th Regiment hoisting his jacket at the Storming of Badajoz on 6th April 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

- Once the Castle was taken by the Third Division, the capture was signalled by Lieutenant Macpherson of the 45th Regiment hoisting his red jacket to the top of the flagpole. The occasion has been marked by the regiment and its successors with the hoisting of a red jacket on the anniversary of the battle.

- When Wellington heard of the number of casualties suffered by the British and Portuguese armies in the assault on Badajoz, he broke down and burst into a ‘passion of tears’.

- It would seem that the British army’s lack of expertise in siege operations told heavily against Wellington. Fortescue expresses the view that once the Main Breach had been retrenched by the French, it became the strongest part of the fortifications. In any case no British soldier managed to scale the breach, so that the retrenchment remained untested. Badajoz was captured due to the success of the two attacks on parts of the fortifications that had not been bombarded and consequently were not considered to be at risk by the French, who were unprepared at those points.

- The attacks by Picton’s Third Division and Leith’s Fifth Division were originally intended by Wellington to be feint attacks only. It was due to the pleadings of the two generals that they were permitted to carry out a full attack in addition to the feint. It was these two full attacks that won the city for Wellington.

- Lieutenant Colonel Grey, commanding the 30th Regiment in Leith’s Fifth Division, was a great friend of Sir John Moore. After serving in 32 general engagements unscathed, Grey received a mortal wound leading his regiment in the attack on the San Vincente bastion. Grey’s wife urged Grey always to carry a tourniquet into battle in case he was wounded. On this occasion Grey omitted to have a tourniquet with him and bled to death. Grey’s apparent wish was that, if fatally wounded in battle, he would receive the same wound that killed his friend Sir John Moore. His wish was granted. Grey was awarded a posthumous Peninsular Gold Medal.

- During the storming of the San Vincente bastion, Private George Hatton of the 4th King’s Own Regiment’s light company bayonetted the ensign carrying the colours of the Regiment of Hesse Darmstadt in the French service and captured the colours. The next day Hatton presented the colours to Wellington. Hatton was presented with a medal by his comrades. The medal is in the museum of the King’s Own Border Regiment in Carlisle Castle.

- Fortescue wrote: ‘. the storm of Badajoz remains and must always remain one of the great deeds of the British army, one of those actions that show forth above others the might and prowess of the British soldier.’

- It is said that some British commanders told their troops before the attack that they were free to loot Badajoz after its capture.

- During the rioting by British soldiers after the capture of Badajoz, General Philippon, the commander of the French garrison and his daughters were protected by two British officers with drawn swords.

- Following the capture of Badajoz, two Spanish sisters took refuge from the rioting in the camp of the 95th Rifles. The younger, 14 years of age, subsequently married the Brigade Major, Harry Smith and accompanied him across Spain for much of the rest of the campaign. General Sir Harry Smith later became governor of Natal in Southern Africa. The town of Ladysmith was named after his Spanish wife.

- General Philippon was taken to Britain where he lived in Oswestry on parole. Philippon is said to have broken his parole and escaped to France on a smuggler’s ship in July 1812. He commanded a division at the Battle of Leipzig and was captured with the surrender of St Cyr’s corps. Philippon left the French army in 1814.

References for the Storming of Badajoz:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

Redcoats against Napoleon by Carole Divall, an account of the 30th Regiment in the Peninsular War, contains an interesting description of the regiment’s involvement in General Leith’s Fifth Division’s attack on the San Vincente bastion and the subsequent disorders.

The previous battle in the Peninsular War is the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo

The next battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of Villagarcia

27. Podcast of the Storming of Badajoz: Wellington’s capture, on 6th April 1812, of the second French base on the Portuguese border, the southern gateway for the British invasion of Spain, during the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts