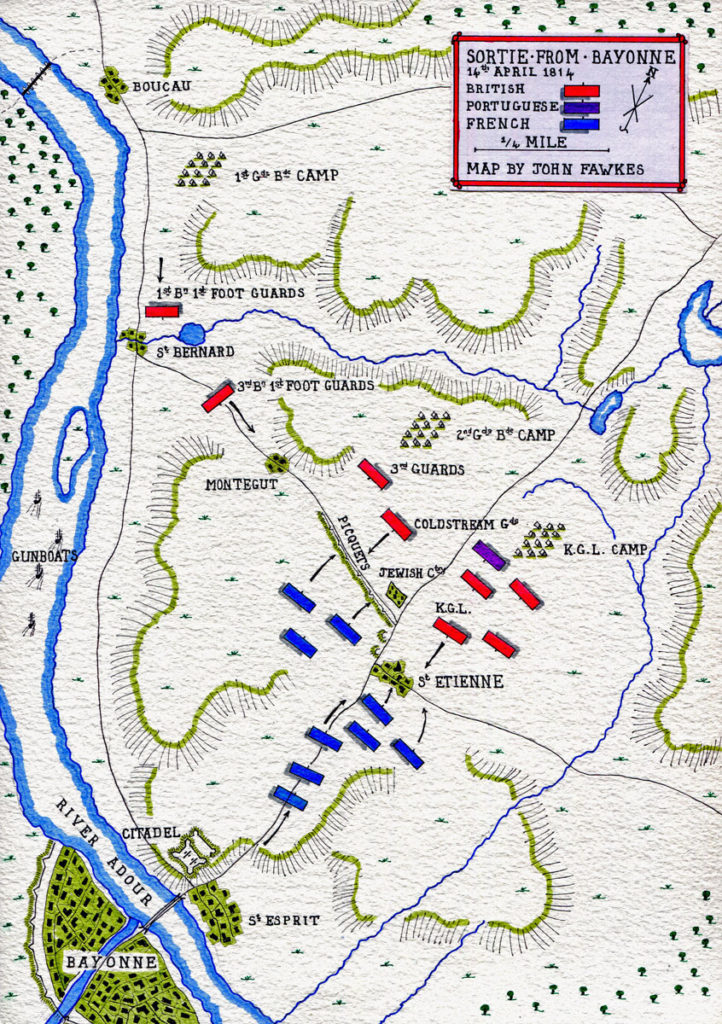

The terrible night-time clash outside Bayonne on 14th April 1814, that marked the end of the Peninsular War, but occurred after the abdication of the Emperor Napoleon on 4th April 1814

51. Podcast on the Sortie from Bayonne: the terrible night-time clash outside Bayonne on 14th April 1814, that marked the end of the Peninsular War, but occurred after the abdication of the Emperor Napoleon on 4th April 1814: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Toulouse

The next battle in the British Battles Sequence is the Battle of Cape St Vincent

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Sortie from Bayonne: 14th April 1814

Place of the Sortie from Bayonne: The city of Bayonne in the south-west corner of France.

Combatants at the Sortie from Bayonne: British, King’s German Legion and Portuguese troops against the French.

Commanders at the Sortie from Bayonne: Major-General Sir John Hope, followed, after his wounding and capture, by General Howard, commanded the British, Portuguese and Spanish Corps blockading Bayonne.

General Thouvenot, French governor of Bayonne, commanded the troops that carried out the Sortie from Bayonne.

Size of the armies at the Sortie from Bayonne:

The French garrison of Bayonne comprised around 14,000 men. Of this number, around 5,000 carried out the Sortie supported by the guns of the Citadel of Bayonne.

The British force on the north bank of the River Adour resisting the Sortie numbered around 6,000 men from the First and Fifth Divisions.

Winner of the Sortie from Bayonne:

The French sortie from Bayonne was repelled after a night of heavy fighting.

Orders of Battle:

British order of battle:

First Division (Howard): Maitland’s Brigade: 1st/1st Foot Guards, 3rd/1st Foot Guards, Stopford’s Brigade: 1st/Coldstream Guards, 1st/3rd Foot Guards, 1 Co 5th/60th. Hinüber’s Brigade: 1st, 2nd and 5th Line Battalions and 1st and 2nd Light Battalions, King’s German Legion.

Fifth Division (Colville): Hay’s Brigade: 3rd/1st Royal Scots, 1st/9th, 1/38th, 2nd/47th and 1 Co Brunswick-Oels.

Major General Bradford’s Portuguese Brigade: 13th and 24th Line Regiments and 5th Caçadores

British, KGL and Portuguese Regiments involved in the battle:

1st/1st Foot Guards, 3rd/1st Foot Guards, 1st/Coldstream Guards, 1st/3rd Foot Guards, 1 Co 5th/60th.

3rd/1st Royal Scots, 1/38th, 2nd/47th Regiments

King’s German Legion:

1st, 2nd and 5th Line Battalions and 1st and 2nd Light Battalions,

Portuguese:

13th Line Regiment and 5th Caçadores

French regiments involved in the battle:

5th and 27th Light Regiments

64th, 66th, 82nd, 94th, 95th, 119th and 130th Line Regiments

Background to the Sortie from Bayonne:

Bayonne is a major city in the south-west corner of France. Lying on the estuary of the River Adour, Bayonne was a major obstacle to Wellington’s continued advance into France in 1814 and a necessary port for the supply of Wellington’s army.

Bayonne remained in French hands until the end of the Peninsular War.

The garrison of Bayonne in 1814 was commanded by General Pierre Thouvenot.

Before Marshal Soult marched to Toulouse in March 1814, following the Battle of Orthez, Soult reinforced Thouvenot’s garrison in Bayonne with Abbe’s Division, increasing the garrison to 14,000 men.

Wellington left General Sir John Hope’s Corps to blockade and capture Bayonne, while he pursued Soult to Toulouse with the rest of his army.

The war against France was coming to an end. Every day news was expected from the north that Napoleon ceased to be Emperor of France, with an end to hostilities.

Expectation of an end to the war persuaded both Hope and Wellington to defer an all-out assault on Bayonne, which must incur substantial casualties to both sides and would probably turn out to be unnecessary.

The French garrison of Bayonne intended otherwise and was planning a vigorous attack on the besiegers.

It is unclear whether the impetus for a French sortie from Bayonne came from the governor, General Pierre Thouvenot, or from ardent supporters of the Emperor Napoleon among his senior officers and staff.

Wellington directed Hope that he was to maintain a blockade of the city, until the British siege train came up, when he would be expected to capture the Bayonne Citadel, situated on the north bank of the River Adour.

The British siege train arrived at Bayonne on 13th April 1814.

The French sortie was initially planned for 4th April 1814, but was delayed due to the continuing storms.

It is far from clear what the French hoped to achieve by a sortie, even if successful; possibly destruction of a section of the entrenchments surrounding the city.

On around 8th April 1814, word reached Hope from the French Royalists in Bordeaux, headed by Napoleon’s erstwhile diplomat, Talleyrand, that the Emperor Napoleon had abdicated on 4th April 1814 and that the war was over.

This information was passed informally to French officers on the picquet lines outside Bayonne, but was not believed by Thouvenot or his officers.

The garrison of Bayonne was short of supplies and it was clear to the French troops that the war was all but lost. In addition, there was an informal truce with the besieging troops. These factors led to significant numbers of French soldiers deserting from Bayonne and either making their way home or surrendering to the British.

Sortie from Bayonne:

The new date for the French Sortie from Bayonne was set for the early morning of 14th April 1814.

The attack was to be northwards from the Bayonne Citadel upon the British entrenchments along the road between Boucau in the west and St Etienne on the main road from Bordeaux to Toulouse.

General Hay’s Brigade of Colville’s Fifth Division manned the picquets and fortified posts in St Etienne.

To the west of St Etienne, Stopford’s Guards Brigade held the cross-roads and the Jewish Cemetery in the north-west corner of the cross-roads, with 1 company in St Etienne and provided the picquets along the road to Boucau.

The picquets from Stopford’s Brigade were that night commanded by Captain Willoughby Cotton of the 3rd Foot Guards.

Maitland’s Guards Brigade was in camp near Boucau.

Hinüber’s KGL Brigade was in camp to the north of St Etienne.

At 1am on 14th April 1814, a French deserter came into the British picquets with word of an impending French attack.

The general officer on duty in the area was General Hay of the Fifth Division, whose brigade held St Etienne.

Napier says that Hay spoke no French and took the deserter to the King’s German Legion brigade commander, General Hinüber, whose brigade camp lay behind St Etienne.

In the light of the deserter’s information, the British formations in the area were alerted and put under arms.

The first French move was a feint attack to the south-west of Bayonne towards Anglet launched at 3am on 14th April 1814. This feint attack was shortly afterwards followed by the main assault.

Three French columns, comprising 5,000 men, left the Bayonne Citadel around 3am.

French gunboats sailed into the estuary and began bombarding the British positions along the shore, giving rise to fears for the safety of the bridge of boats across the River Adour in the mouth of the estuary.

The first two French columns attacked St Etienne and the line of picquets along the Boucau-St Etienne Road.

The French came up at the double out of the dark, supported by blasts of gunfire from the citadel and charged through the British picquet line; the right column taking the St Etienne cross-roads within 15 minutes of the commencement of the assault; the left column capturing the St Bernard road as far as Montegut

The British picquets along the St Etienne to Montegut road from the Coldstream and 3rd Regiments of Foot Guards were overwhelmed and almost entirely killed or captured, after defending themselves with the bayonet.

The French supporting column burst through the cross-roads and rushed north up the Bordeaux road, driving the British troops before them.

General Hay was killed in St Etienne early in the fighting, his last order being to hold the St Etienne church to the last.

Sir John Hope, cantering up the road from Boucau to St Etienne with his staff in answer to the alarm, rode straight into the French troops and was wounded twice.

Sir John’s horse was shot dead and fell, trapping his leg. The British commander was captured together with three of his staff who rode back to assist him.

News of Sir John Hope’s capture reached his deputy, General Howard, who took command.

In the meantime, the French advance through St Etienne had been stopped by a vigorous defence of one of the houses in the centre of St Etienne by Captain Forster with a party of troops from the 38th Regiment.

The French were unable to dislodge Foster and his men.

In the British centre, on the western side of the Bordeaux road, a force of British Foot Guards held the Jewish cemetery and again could not be forced out.

General Hinüber launched his brigade of the King’s German Legion in a counter-attack into St Etienne, headed by the 2nd KGL Light Infantry, driving the French out of the village and relieving Captain Forster’s party holding out in the house.

Hinüber’s attack was supported by Portuguese troops from the 13th Line Regiment and 5th Caçadores.

To the west of St Etienne, the 3rd Battalion of the 1st Foot Guards from General Maitland’s Brigade attacked the French from the direction of Boucau, while Colonel Guise, commanding the Second Guards Brigade after the wounding of General Stopford, launched the 1st Battalion of the Coldstream Guards in a counter-attack on the French in the area of the hollow road.

Fearing to be cut off from Bayonne, after a hard-fought resistance, the French fell back to the citadel.

During the course of the French retreat, a British gun was brought into action firing into the French eastern flank, causing them further casualties.

Casualties in the Sortie from Bayonne:

French casualties in the Sortie from Bayonne were 900 killed and wounded and 13 taken prisoner.

British casualties were 678 killed and wounded with 236 taken prisoner, including Major General John Hay of Colville’s Fifth Division killed and Major General Sir John Hope, the British commander, wounded and captured by the French with 3 of his staff officers. Major General Stopford, commanding the Second Guards Brigade, was wounded.

Portuguese casualties were 33 killed and wounded.

Casualties of the General Staff and the British Foot Guards:

General Staff: 1 captain killed, 3 captains and 1 lieutenant wounded and captured.

Maitland’s Brigade:

1st/1st Foot Guards: 1 soldier killed and 2 sergeants and 4 soldiers wounded.

3rd/1st Foot Guards: 2 soldiers killed: 2 lieutenants, 1 sergeant and 30 soldiers wounded: 1 captain, 3 sergeants and 15 soldiers captured.

Stopford’s Brigade:

1st/Coldstream Foot Guards: 1 captain, 1 lieutenant, 1 sergeant, 1 drummer and 30 soldiers killed: 1 captain, 2 lieutenants, 2 ensigns, 11 sergeants and 111 soldiers wounded: 2 sergeants and 82 soldiers captured.

1st/3rd Foot Guards: 35 soldiers killed: 4 lieutenants, 1 staff, 8 sergeants, 3 drummers and 95 soldiers wounded: 1 ensign, 1 sergeant and 56 soldiers captured.

Several of the wounded men subsequently died, including 2 lieutenants in the 1st/3rd Foot Guards.

Aftermath to the Sortie from Bayonne:

Finally, on 27th April 1814, General Thouvenot received a letter from Marshal Soult informing him of the abdication of the Emperor Napoleon and ordering him to cease fighting.

The Peninsular War was over.

Battle Honours and Medal for the Sortie from Bayonne:

The Military General Service Medal 1848 was issued to all those serving in the British Army present at specified battles during the period 1793 to 1840 and who applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one of the 11 clasps.

The Sortie from Bayonne was not one of those clasps.

No regimental battle honour was issued for the Sortie from Bayonne.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Sortie from Bayonne:

- The French attack seems to have been launched in the middle of the night due to awareness that a deserter was warning the British. The fighting during the attack on St Etienne and the picquets along the road was conducted, unusually, with the bayonet, leading to extensive dangerous wounds on both sides. Napier attributes the failure of the French attack to the resolute defence of the house in St Etienne by Captain Forster and his men from the 38th Regiment and the defence of the Jewish Cemetery by the Second Guards Brigade.

- Wellington was outraged that General Thouvenot should initiate such a destructive battle when it was known that the Emperor Napoleon had abdicated and the war was effectively over. Wellington called Thouvenot a ‘Blackguard’.

- Sir John Hope’s adc, Lieutenant George Moore, 52nd Light Infantry, was a nephew of Sir John Moore, the British commander-in-chief killed at Corunna in 1809. Lieutenant Moore and the group of Hope’s staff officers, on encountering the French attack, rode off to escape capture. They realised that Sir John Hope was not with them and rode back to rescue him. All were captured, with Moore and Captain Herries severely wounded.

- The Second Guards Brigade picquet line, that received the French attack along the Boucau to St Etienne road, was commanded by Captain Willoughby Cotton of the 3rd Foot Guards. Cotton attended Rugby School, where he led a revolt against the headmaster, who called out the local militia to quell the rebellious pupils and expelled Cotton. This wayward antecedent does not seem to have hindered Cotton in obtaining a commission in a prestigious regiment.

- Gronow recounts how Captain Willoughby Cotton was taken prisoner by French soldiers during the Sortie from Bayonne, but secured his release by handing over his watch and the money he was carrying, a Spanish dollar. The French soldiers gave him a beating before releasing him ‘because the sum was so mean’.

- Gronow records that Captain Townsend of the Guards was also captured, hinting that he was too corpulent to outpace the pursuing French.

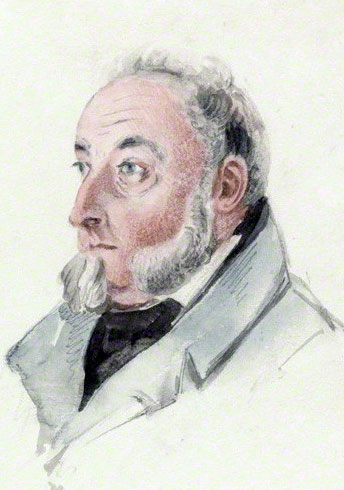

- Robert Batty, whose pictures are shown above, served as an officer in the 1st Foot Guards in the Western Pyrenees and was wounded at the Battle of Waterloo. Batty took a degree in medicine at Gaius College, Cambridge in 1813, before joining the army. A talented artist, Batty toured Europe, after leaving the army, executing sketches and pictures of various landmarks and cities, publishing books and becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society. Batty wrote and illustrated accounts of the campaigns he experienced.

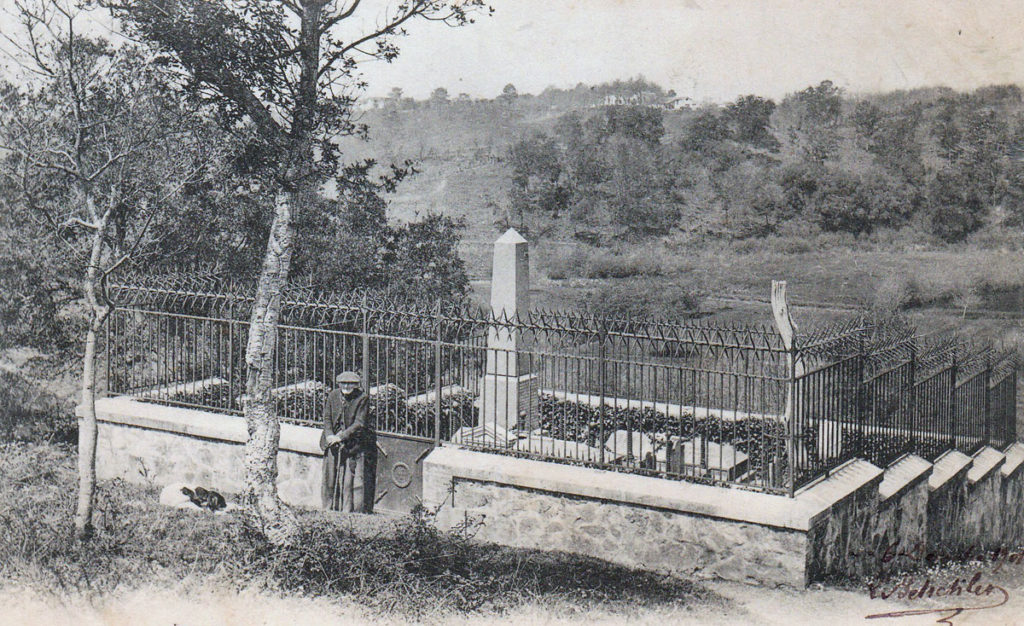

- The Sortie from Bayonne is of poignant significance for the British Foot Guards, in view of the large number of officers and soldiers killed and wounded. British graves from the battle were restored and placed in a single graveyard through the efforts of P.A. Hurt, a British resident of Bayonne, in the second half of the 19th Century. Queen Victoria visited the graveyard in 1889 and King Edward VII visited the graveyard in 1909.

References for the Sortie from Bayonne:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

51. Podcast on the Sortie from Bayonne: the terrible night-time clash outside Bayonne on 14th April 1814, that marked the end of the Peninsular War, but occurred after the abdication of the Emperor Napoleon on 4th April 1814: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Toulouse

The next battle in the British Battles Sequence is the Battle of Cape St Vincent