Wellington’s retreat to Ciudad Rodrigo following the unsuccessful Attack on Burgos in the autumn of 1812 in the Peninsular War

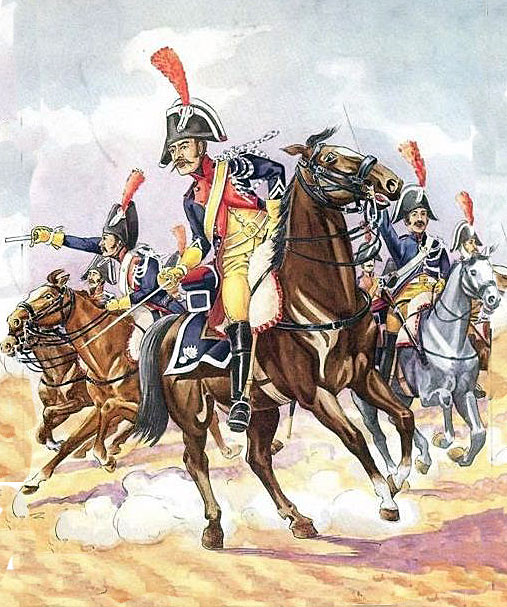

Capture of General Paget by French Dragoons on 17th November 1812 during the Retreat from Burgos in the Peninsular War

Podcast on the Retreat from Burgos: Wellington’s retreat to Ciudad Rodrigo following the unsuccessful attack on Burgos in the Autumn of 1812 in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Attack on Burgos

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Morales de Toro

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Retreat from Burgos: 21st October to 19th November 1812

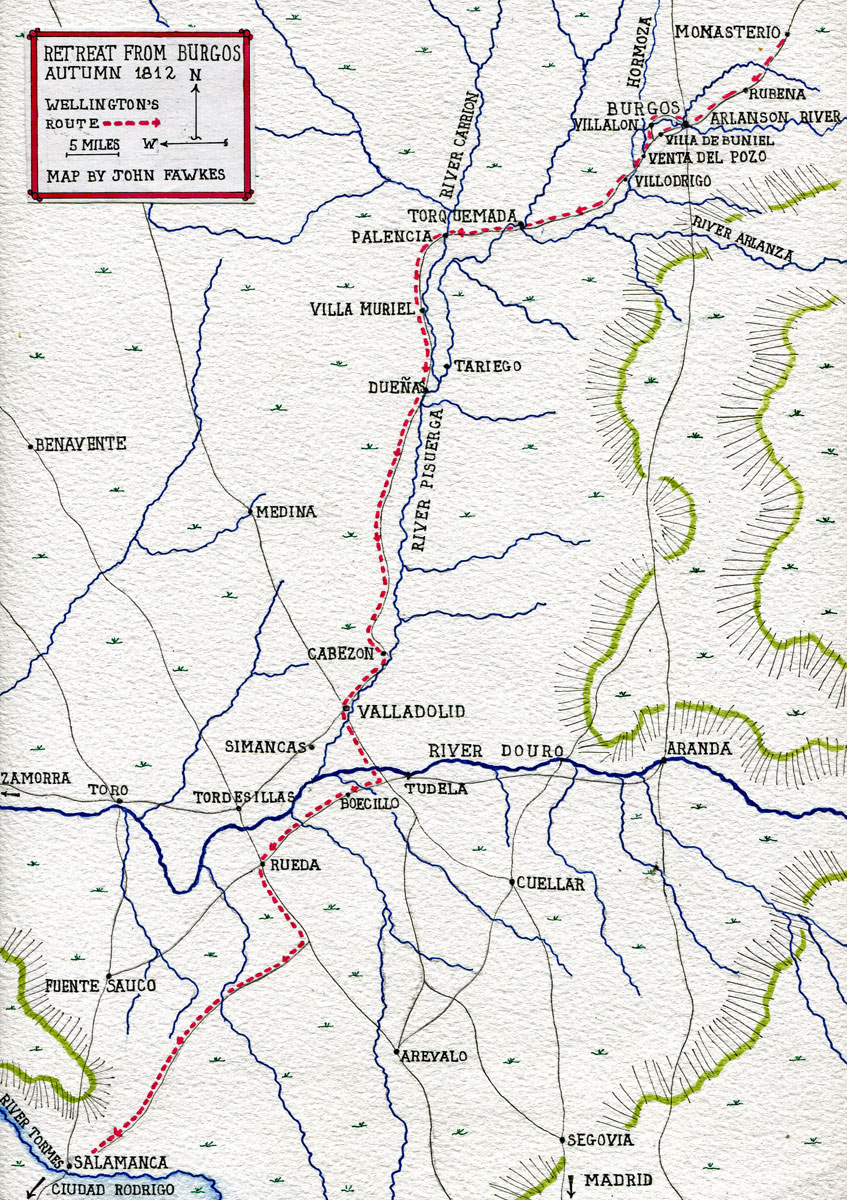

Place of the Retreat from Burgos: In Spain, down the main road from Burgos to the Portuguese border at Ciudad Rodrigo.

Combatants at the Retreat from Burgos: British, Portuguese and Spanish against the French

Commanders at the Retreat from Burgos: Lieutenant General the Earl of Wellington against General Souham, Marshal Soult and Joseph Bonaparte.

Size of the armies at the Retreat from Burgos: around 65,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish troops against a final total of around 115,000 French troops.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Burgos:

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers, and stovepipe shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments wore dark green jackets and trousers.

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

Highland regiments wore the kilt with red tunics and black ostrich feather caps.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and black fore and aft cocked hats. The change in uniform brought in during 1812 saw the British heavy cavalry adopt ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light dragoons wore light blue uniform coats and a leather helmet with a fur crest running front to back.

From 1812, the British light cavalry increasingly adopted hussar uniforms, with some regiments changing their title from ‘light dragoons’ to ‘hussars’.

2nd Light Infantry Battalion King’s German Legion: Battle of Venta del Pozo and Villodrigo on 23rd October 1812 in the Peninsular War

The King’s German Legion (KGL) was formed largely from the old disbanded Hanoverian army. The KGL owed its allegiance to King George III of Great Britain, as the Elector of Hanover, and fought with the British army. The KGL comprised both cavalry and infantry regiments. KGL uniforms followed the British.

The Portuguese army uniforms increasingly during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

The Spanish army essentially was without uniforms, existing as it did in a country dominated by the French. Where formal uniforms could be obtained, they were white.

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe, and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry, the horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket. The musket could be fired at three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for a hundred metres or so. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, which fitted the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, and a sword bayonet.

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who invented it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was not able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create his powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns with the speed of the French columns of infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

Winner of the Retreat from Burgos:

This was a fighting retreat conducted over a distance of some 200 miles, successfully carried out in difficult circumstances by Wellington.

Background to the Retreat from Burgos:

In June 1812, after capturing Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz, the essential bases for an incursion into Spain, Wellington advanced up the main road, north-east towards Salamanca, Valladolid, Burgos, Vitoria and the French border at the northern end of the Pyrenees.

On 22nd July 1812, Wellington heavily defeated the French Army of Portugal, commanded by Marshal Marmont, at the Battle of Salamanca, causing the Army of Portugal to retreat north-east towards Burgos and Joseph Bonaparte to leave the Spanish Capital City of Madrid for the south-east of Spain.

On 13th September 1812, Wellington began an attack on the French garrison in Burgos Castle.

The French response to Wellington’s victory and advance was to assemble their various armies from across Spain, under Joseph Bonaparte and his chief of staff, Marshal Jourdan, to meet the threat of Wellington’s incursion.

This was a time-consuming process. Communications for the French across Spain were difficult due to the activities of the Spanish guerrilla bands across the country, intercepting French couriers unless strongly escorted.

The senior French commanders were little inclined to co-operate and all held Joseph Bonaparte in contempt.

Nevertheless, by the early autumn of 1812 the process of combination was under way.

Marshal Soult, with his Army of the South, met Joseph with the Army of the Centre at Almanza to the south of Madrid and in the middle of October 1812 Soult and Joseph began their advance on Madrid, with a combined army of 60,000 men and 84 guns.

In their path stood Hill’s force of some 20,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish troops.

North of Burgos, the Army of Portugal, under the command of General Souham, recently restored in morale and discipline by the efforts of Clausel and reinforced with drafts from France to take it to 45,000 men, began an advance to relieve the French garrison in Burgos Castle.

In support, marched the Army of the North under Caffarelli, contributing a further 8,000 infantry, 1,000 cavalry and 16 guns.

Souham ordered the concentration of the Army of Portugal at Briviesca, 50 miles north-east of Burgos, on the main road.

Map of Wellington’s retreat from Burgos to Salamanca in the Autumn 1812 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

Retreat from Burgos:

Following the Battle of Salamanca and his occupation of Madrid, Wellington continued his advance north-east towards the French border.

Wellington’s aim was to capture the City of Burgos, lying on this main road, from its French garrison.

Wellington’s attack on Burgos took place between 19th September and 25th October 1812 and was a failure.

With French armies gathering in overwhelming strength, Wellington faced the prospect of retreating the length of the main road, to where he had begun the year’s campaigning, the city of Ciudad Rodrigo on the Portuguese border.

Souham’s advance:

With Wellington still conducting his attack on the French garrison in Burgos Castle, the line of demarcation between the French and the British lay around the village of Monasterio, 15 miles north-east of Burgos, where the main road crossed a small stream.

On 18th October 1812, the French forced the line of the stream and captured a piquet of Brunswickers.

Wellington took up a position along a ridge at the village of Rubena, 5 miles from Burgos, from which the British First Division repelled an advance by Maucune with 2 divisions of infantry and some cavalry, forcing the French back some distance. Wellington resolved to hold his position and give battle to Souham.

Wellington was unaware that Souham was reinforced by Caffarelli’s Army of the North, giving him a combined force of 54,000 men, against which Wellington could put into the field only 21,000 British and Portuguese with 12,000 Spanish troops.

At 2pm on 21st October 1812, Wellington received a letter from Hill, commanding the British, Portuguese and Spanish troops covering Madrid, announcing the advance of Soult and Joseph on the Spanish capital and his own enforced withdrawal. It was clearly time for a general retreat.

At sunset Souham’s army appeared and halted at a distance from Wellington’s position.

Sir Colin Halkett, commander of the Brigade of King’s German Legion Light Infantry: Retreat from Burgos Autumn 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by William Salter

The retreat through Burgos:

Wellington directed his army to retreat that night by a number of routes and rendezvous at Villa de Buniel, 10 miles south-west of Burgos on the River Arlanson.

A substantial portion of the army, comprising the First, Sixth and Seventh Divisions, with two brigades of Portuguese and a Spanish Division, was to march through the city of Burgos itself, crossing the River Arlanson by the two city bridges.

General Paget, commanding the force, queried the decision in view of the proximity of the French garrison in Burgos Castle. Wellington replied ‘I do not think they will see you.’

Initially Wellington was right. The First and Seventh Divisions crossed the bridges unnoticed by the French in Burgos Castle, the gun wheels muffled and the soldiers carrying their muskets at the trail to give the impression they were no more than crowds of locals crossing the bridges.

Only when a Spanish cavalry regiment galloped across a bridge did the French open a heavy fire on the two bridges, preventing any further crossing.

The Sixth Division was compelled to march around the north of Burgos and cross the river at Villalon, using the route taken by the Fifth Division.

The various detachments of Wellington’s army re-joined the main road to Valladolid beyond Burgos at Villa de Buniel and marched on to Celada del Camino, some 15 miles from Burgos.

Wellington had adroitly disengaged from Souham’s army, passed the awkward obstacle of Burgos Castle and set his army well on its retreat to the south-west.

Action at Venta del Pozo and Villodrigo on 23rd October 1812:

Souham realised in the evening of the following day, 22nd October 1812, that Wellington’s army had marched away and immediately set off in pursuit.

Wellington’s troops crossed the Pisuerga River at Torquemada and Cordovillas, while the rear-guard held back the French advance at Venta del Pozo.

The rear-guard, commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Stapleton Cotton, comprised Anson’s Brigade of Light Cavalry (the British 11th, 12th and 16th Light Dragoons numbering some 700 men), Bock’s Brigade (1st and 2nd King’s German Legion Dragoons numbering 300 men), Bull’s troop of horse artillery, the Spanish guerrilla cavalry of Marquinez and Halkett’s Brigade of the 1st and 2nd King’s German Legion Light Infantry Battalions.

Cotton positioned Anson’s Brigade on the French side of the bridge over the Hormoza Stream at Venta del Pozo, with the KGL Light Battalions concealed on the near bank and in the village of Celada.

At 9am on 23rd October 1812, the French cavalry attacked and were repelled twice by Anson’s Brigade, before pushing across the stream, when they came under fire from the KGL light infantrymen and were driven back. The action lasted until midday.

More French cavalry came up and Wellington, taking over command, directed Halkett’s KGL Light Infantry battalions to withdraw down the main road to the south-west, their retreat covered by repeated charges from Anson’s Brigade.

Halkett’s battalions came up with Bock’s Brigade at the village of Villodrigo, greeting their Hanoverian countrymen with enthusiasm.

At Villodrigo, Bock’s Dragoons, numbering only 300 men, were positioned 500 yards behind a canal bridge, with the River Arlanson on their right. Bull’s troop of horse artillery covered the bridge. Halkett’s KGL Light Infantry battalions crossed the bridge and occupied an area of high ground behind the dragoons.

King’s German Legion 1st Dragoons: Action at Villodrigo on 23rd October 1812 during the Retreat from Burgos in the Peninsular War

At 5pm, Anson’s Light Dragoons came down the road in considerable disorder, with the Spanish guerrilla cavalry, after being charged in the flank by a confused mass of guerrillas and French cavalry and having to fight its way back for some miles.

Anson’s men crossed the bridge, closely followed by the French cavalry, inevitably masking Bull’s guns. (there must be considerable doubt as to whether Bull’s troop of horse artillery was in fact present at the action as Fortescue states).

The French cavalry quickly formed line after crossing the bridge and launched an attack.

Bock’s and Anson’s brigades charged the French cavalry, but were carried back by the overwhelming French strength, reforming behind Halkett’s two KGL Light Infantry battalions.

The French charged on to attack Halkett’s battalions, which formed squares and repelled the French cavalry with significant loss. Two unsuccessful charges were delivered against each KGL battalion without success.

The French cavalry drew off and the British rear-guard was enabled to march on to Torquemada.

The French General Caffarelli, in his report on the action, complained that Boyer’s Division rode off to the north at the moment of crisis, thereby failing to ensure the destruction of the British and German cavalry.

Losses to the British and German regiments were 15 officers and 215 soldiers killed and wounded. Halkett’s two battalions suffered only a few men wounded.

French losses are unknown, other than that they lost 32 officers killed and wounded, suggesting overall casualties twice the British and German figures.

French 3rd Hussars: Battle of Venta del Pozo and Villodrigo on 23rd October 1812 in the Peninsular War

The French cavalry involved in the action at Venta del Pozo and Villodrigo comprised these formations:

Curto’s Division: 1st Brigade: 3rd Hussars, 22nd, 26th, 28th Chasseurs: 2nd Brigade: 13th and 14th Chasseurs (115 officers and 1,761 men).

Boyer’s Division: 6th, 11th, 15th and 25th Dragoons (75 officers and 1,599 men).

Light Cavalry Brigade: 1st Hussars and 31st Chasseurs (53 officers and 693 men)

Brigade from Army of the North: 15th Chasseurs, 20th Dragoons, Berg Lancers and Gendarmes (117 officers and 1,606 men)

French Gensdarmes at the Battle of Venta del Pozo and Villodrigo on 23rd October 1812 in the Peninsular War

Torquemada:

Wellington’s army bivouacked around the village of Torquemada on the night of 23rd October 1812.

The wine harvest was complete and the villages in the area contained stores of the new-made wine.

The consequence was wide-spread drunkenness among Wellington’s troops. It is said ‘that 12,000 British troops were helplessly drunk in one moment.’

Fortescue attributes to this episode the beginning of a breakdown in discipline in the British regiments that lasted to the end of the retreat.

Royal Artillery firing on French Hussars: Retreat from Burgos Autumn 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Denis Dighton

The Palencia-Villa Muriel-Dueñas position:

On 24th October 1812, Wellington took up an extended position at the junction of the Carrion and Pisuerga Rivers.

Wellington’s left (the most northern position) lay at Palencia on the River Carrion, his centre at Villa Muriel, also on the Carrion and his right (the most southern position) at Dueñas at the junction of the Rivers Carrion and Pisuerga.

These villages, Palencia, Villa Muriel and Dueñas, were approximately 5 miles apart, each with a bridge over the river and each an inevitable point of conflict between Wellington’s retreating army and Souham’s vigorously pursuing French Army of Portugal.

During the move to this position, the British Sixth Division and some cavalry remained on the east bank of the Carrion north of Torquemada.

The French advanced into Torquemada and attempted to cross the river under British artillery fire. The French came to a halt under the same handicap suffered by Wellington’s army. The French troops found the newly-made wine and became helplessly drunk in their thousands.

The British troops withdrew across the River Carrion and Wellington ordered the destruction of the bridges over the Carrion at the three villages, Palencia, Villa Muriel and Dueñas and the bridge over the Pisuerga at Tariego.

On 25th October 1812, Foy attacked Palencia, while Maucune advanced on Villa Muriel.

Destroying the stone bridges of Spain was not an easy process. A hole had to be bored into the masonry, using hammers and chisels, large enough to take a charge of gunpowder sufficiently powerful to destroy the arch of the bridge. It took a team of soldiers working on the hole, engineer officers to insert and then fire the charge, all protected by a force covering the bridge. The destruction of such a stone bridge could take several hours.

King’s German Legion Dragoon: Battle of Venta del Pozo and Villodrigo on 23rd October 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

The bridge at Villa Muriel was safely destroyed, but only as the French advanced to capture it.

The engineer officer deputed to destroy the bridge at Tariego, hearing, falsely, that the French were already in the village, delayed in going to Tariego and by the time he got there, there was insufficient time to do the work. The French cavalry overwhelmed and captured the demolition party before the bridge could be blown.

Taking the bridge at Tariego gave Souham the opportunity to march on to Tudela on the River Douro and get there before Wellington.

It is reported that the British dragoon, sent with the order to blow the bridge at Palencia, lost his way and failed to reach the Fifth Division, which was responsible for demolishing the bridges, until 8am the following morning, with the result that the demolition work was begun too late.

Chemineau’s Brigade rushed the town and drove out its garrison, comprising the Spanish guerrilla cavalry and the 3rd/1st Regiment (the Royal Scots), capturing the bridge intact with the demolition party.

At Villa Muriel, the British Fifth Division was present in strength behind the destroyed bridge.

It is said that a French dragoon rode up to the river bank and persuaded British soldiers to point out a ford to him, on the pretence that he was trying to desert. The soldiers indicated a ford and the dragoon rode back to his comrades who launched an attack across the disclosed ford.

It would seem more likely that the French identified available fords simply through questioning the inhabitants or by observation. Livestock tended to cross rivers by ford rather than by bridge, which might involve the payment of a toll. Fords regularly used in such a way have a pattern of hoof marks and worn points of access.

Maucune’s troops pushed back the Spanish positioned on the west bank.

Wellington ordered General Oswald, recently appointed to command the Fifth Division, to launch both his brigades in a counter-attack.

Oswald retook the village of Villa Muriel, forcing Maucune back across the River Carrion.

British soldiers on the march: Retreat from Burgos Autumn 1812 in the Peninsular War: a contemporary cartoon

Fifth Division: commanded by Major General Oswald.

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Barnes: 3rd/1st, 1st/9th, 1st and 2nd/38th Foot and 1 company of Brunswick Oels.

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Pringle: 1st and 2nd/4th, 2nd/30th, 2nd/44th Foot and 1 company of Brunswick Oels.

British and Spanish casualties were around 350 killed or wounded, the French probably losing around 700.

With the French over the River Carrion at Palencia and over the River Pisuerga at Tariego, the positions at Villa Muriel and Dueñas were no longer tenable and Wellington ordered the resumption of the retreat towards Valladolid.

The march began in the evening of 25th October 1812, the army marching through the night, the Fifth Division alone remaining in position for a time.

On the morning of 26th October 1812, the army reached Cabezon where it crossed the River Pisuerga and took up further positions on the east bank of the river, while the Seventh Division marched on to secure the bridges across the River Pisuerga at Valladolid and Simancas and across the Douro at Tordesillas.

On 27th October 1812, Souham’s army came up to Cabezon, having repaired and crossed the broken bridges.

With the more open country, Wellington was able to see the size of the French army that faced him. Substantially outnumbered and with the French armies of Soult and Joseph advancing on Sir Rowland Hill via Madrid, it became clear that Wellington could not maintain a position on the Douro and would need to retreat further to the south-west.

Wellington wrote to Sir Rowland Hill warning him of the danger.

Valladolid and Simancas:

On 28th October 1812, the French army attacked the bridges at Valladolid and Simancas.

The British Seventh Division repelled the French attack at Valladolid.

The bridge at Simancas was held by Colonel Halkett’s Brigade of the 1st and 2nd KGL Light Infantry Battalions, with the Brunswick Battalion and 2 guns.

Halkett sent the Brunswickers to hold Tordesillas while his two KGL Light Infantry Battalions held back Foy’s Division as it attempted to storm the bridge at Valladolid.

The preparations finally being complete, the British engineers blew the charge and destroyed the Valladolid bridge.

Tordesillas:

The bridge in Tordesillas was broken in June 1812. All the Brunswickers had to do was ensure that the French were unable to cross the river, take over the ruins of the bridge and repair it.

Following the destruction of the bridge at Valladolid, Foy despatched troops from his division to Tordesillas.

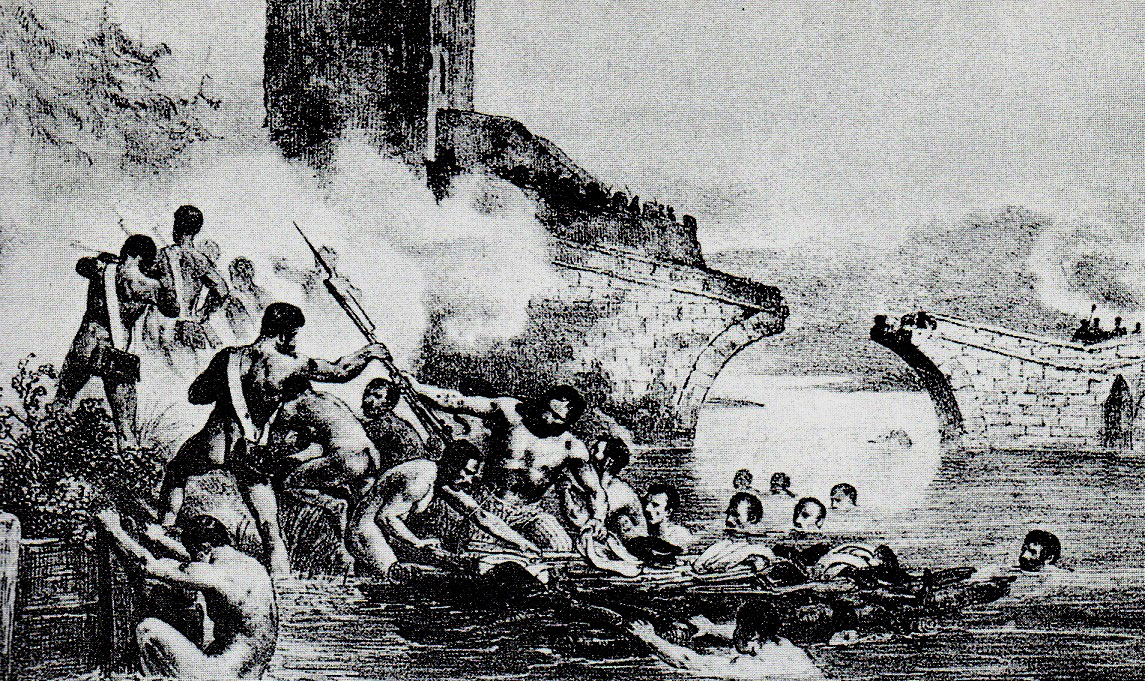

French 6th Light Infantry commanded by Captain Guingret swimming the River Douro at Tordesillas during Wellington’s Retreat from Burgos Autumn 1812 in the Peninsular War

Arriving at the northern side of the damaged bridge, a party of volunteers from the French 6th Light Infantry swam across the River Douro during the night, pushing their weapons on a makeshift raft.

Crossing, naked, to the far bank, the French light infantry, without dressing, stormed the tower held by the Brunswickers, leaving the French in control of the ruined bridge.

On the evening of 28th October 1812, Wellington, after destroying the bridges at Cabezon and Valladolid, crossed the Douro to Boecillo. Souham could be seen marching west along the Douro.

During the night, Wellington heard of the loss of the damaged bridge at Tordesillas. He marched his army to that town and sent parties on to destroy the bridges at Zamora and Toro.

While at Tordeslilas Wellington, to his relief, received notice from Hill that he was now able to march through the Guardarrama Mountains and join the main army.

Operations around Salamanca:

Soult, with the French Army of the South and Joseph, with the French Army of the Centre, began their advance from the south-east on Madrid by 17th October 1812.

On 30th October 1812, Soult carried out a reconnaissance of Hill’s position and attacked the British brigade at Puenta Larga. The bridge in the town was due to be blown, but the mine failed and had to be re-laid.

In the meantime, the British 47th Regiment and the 95th Rifles were forced to defend the bridge, until it was successfully blown.

After re-entering Madrid, Joseph and Soult joined the French Army of Portugal, now under Souham, giving Joseph a combined force of some 90,000 men, including 11,000 cavalry and some 200 guns.

Sir Rowland Hill, withdrawing before Soult’s advancing troops, joined Wellington on the River Tormes, giving Wellington a combined force of 52,000 British and Portuguese and 12,000 Spanish troops, of which 3,500 were cavalry and 108 guns.

With this considerable imbalance in force, the contestants took up position on either side of the River Tormes, to the east of Salamanca.

On 14th November 1812, Soult’s Army of the South began crossing the River Tormes around Ejeme, 3 miles upstream from Alba de Tormes.

Soult’s move, although slow and deliberate, outflanked Wellington’s positions along the River Tormes and provoked him into a general retreat, which did not end until his army marched, exhausted, into Ciudad Rodrigo, the rear-guard arriving on 19th November 1812.

On 17th November 1812, as Wellington’s army began the final stage of its retreat, his deputy General Sir Edward Paget was surprised unescorted by French Dragoons and taken prisoner. Paget’s loss was keenly felt by Wellington and the Army.

While Wellington was back where he had begun the 1812 campaign, it was not considered that he was in any way defeated. He had advanced a considerable distance, beaten the French Army of Portugal and driven it north. He had compelled Joseph to escape from his capital city in an ignominious rush and he had forced Soult to abandon his fiefdom in the south of Spain.

One of Wellington’s principal aims was to cause the French to concentrate their armies against him, giving the guerrilla bands all over Spain the opportunity to operate against French interests without interruption.

This Wellington certainly achieved in the autumn of 1812.

1813 would see Wellington resuming his advance against the French in Spain. This time with more permanence.

In the meanwhile, Wellington’s army needed time to recover from an arduous year.

Follow-up to the Retreat from Burgos:

Once Wellington’s troops were established in Ciudad Rodrigo and in the various cantonments behind the city in Spain and Portugal, Wellington began the task of re-building his army. Substantial re-inforcements were received from Britain over the winter of 1812/13.

Wellington, on arrival at Ciudad Rodrigo, issued a document to his divisional and brigade commanders expressing extreme dissatisfaction at the breakdown in discipline during the retreat from Burgos. The contents of this document became known throughout the army and caused considerable outrage.

The retreat had been conducted in exacting circumstances and with a near collapse in the system of supply. The troops and junior officers considered they had conducted themselves creditably, particularly in view of the length of the campaign season in 1812, some 10 months, and the substantial distances they had been required to march; for some regiments in excess of 500 miles during the year. They had conducted three assaults on cities and one major battle, in addition to minor skirmishes.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Retreat from Burgos:

Silver Medal issued in Germany to commemorate the Battle of Venta del Pozo during the Retreat from Burgos Autumn 1812 in the Peninsular War

- Stanhope recounted how at Villodrigo on 23rd October 1812, ‘the riflemen brought the enemy down as if they had been partridges’, when describing the conduct of Halkett’s KGL Light Infantrymen.

- The action at Venta del Pozo, on 23rd October 1812, was carried as a battle honour by the two KGL Light Infantry Battalions and their successor corps until 1918, when the Imperial German Army ceased to exist at the end of the First World War.

- The presence of Bull’s troop of horse artillery at the action of Venta del Pozo on 23rd October 1812 is recorded in Fortescue. Beamish in his ‘History of the King’s German Legion’, the authoritative account of the KGL’s actions in the Peninsular and Napoleonic Wars, published in 1832 from eye witness accounts taken from members of the KGL, makes no mention of the presence of Bull’s troop of horse artillery at the action at Venta del Pozo. This account is detailed and was clearly important for Beamish’s History, in view of the distinguished conduct of the KGL Light Battalions and the involvement of Bock’s KGL Dragoon Brigade. It may be that Fortescue is mistaken in placing Bull’s troop in the action. It is hard to see how the troop could have escaped capture by the French if it had been present.

- At Venta del Pozo on 23rd October 1812, Sir Stapleton Cotton, the commander of the rear-guard, is described in Beamish’s History of the King’s German Legion as being rescued from a French dragoon by his orderly, Private Schutte of the KGL 1st Hussars, who cut down the French trooper.

- Private Eckhard Bohne of the 2nd Light Battalion of the King’s German Legion was awarded the Hanoverian Guelphic Medal for his conduct at Vento del Pozo and at Vittoria, where he was wounded but refused to leave the ranks until the end of the day. He was also awarded the Hanoverian Medal for Volunteers.

- During the long retreat from Burgos to Ciudad Rodrigo, much of it in driving rain, the British and Portuguese artillery were forbidden from taking up straggling soldiers, many of them wounded, on their carriages and guns for fear of overloading the horses and thereby losing the guns.

References for the Retreat from Burgos:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

Podcast on the Retreat from Burgos: Wellington’s retreat to Ciudad Rodrigo following the unsuccessful attack on Burgos in the Autumn of 1812 in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

Podcast on the Retreat from Burgos: Wellington’s retreat to Ciudad Rodrigo following the unsuccessful attack on Burgos in the Autumn of 1812 in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Attack on Burgos

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Morales de Toro