Wellington’s decisive defeat of Joseph Bonaparte’s French army on 21st June 1813 in North-Eastern Spain in the Peninsular War

28. Podcast of the Battle of Vitoria: Wellington’s decisive defeat of Joseph Bonaparte’s French army on 21st June 1813 in North-Eastern Spain in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

28. Podcast of the Battle of Vitoria: Wellington’s decisive defeat of Joseph Bonaparte’s French army on 21st June 1813 in North-Eastern Spain in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of San Millan and Osma

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Storming of San Sebastian

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of Vitoria: 21st June 1813

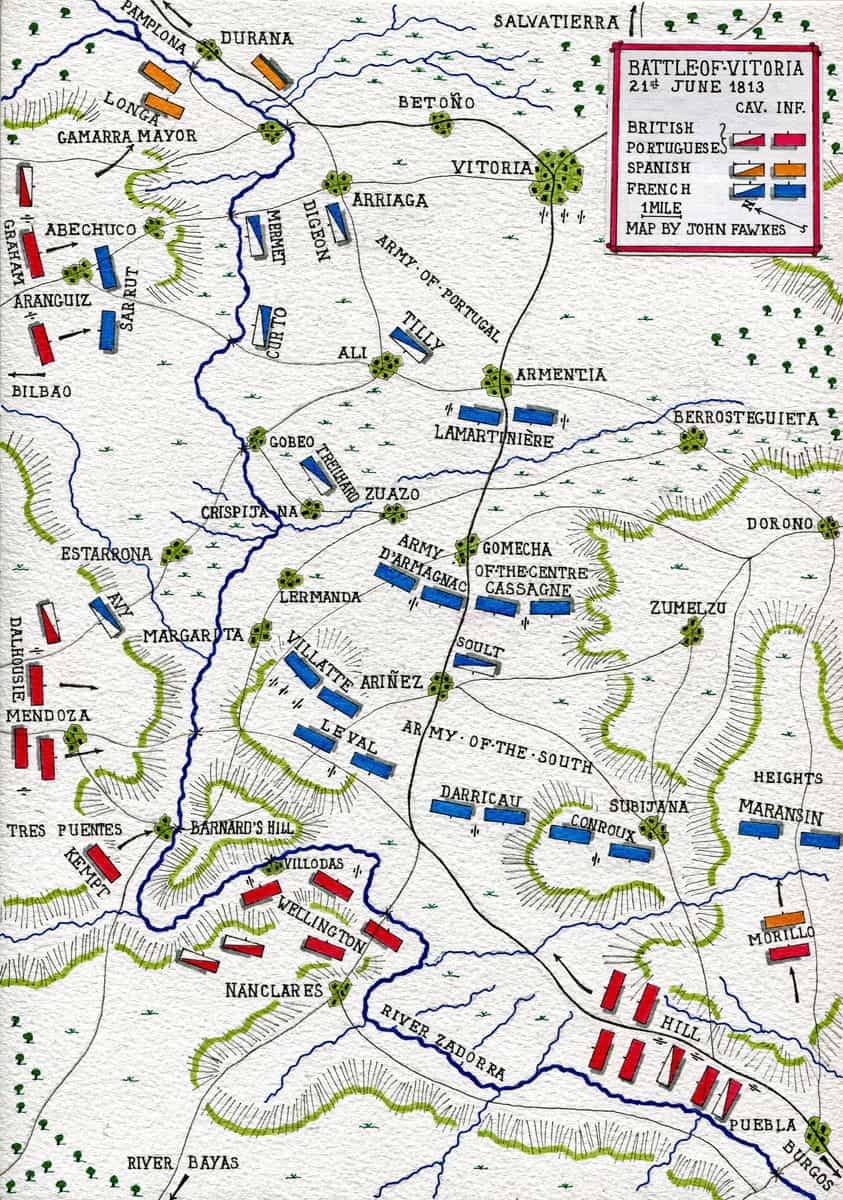

Place of the Battle of Vitoria: in North-Eastern Spain, to the South of Bilbao and near the French border.

Combatants at the Battle of Vitoria: British, Portuguese and Spanish against the French.

Commanders at the Battle of Vitoria: The Marquis of Wellington (from 1814, the Duke of Wellington) against Joseph Bonaparte, brother of the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, who had imposed him on the Spanish people as their king.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Vitoria: Wellington’s army comprised 52,000 British and 28,000 Portuguese troops. An army of 25,000 Spanish troops co-operated in the campaign. Wellington’s army had 90 guns.

The French army, drawn from the Army of the South, the Army of the Centre and the Army of Portugal, comprised 50,000 troops (including 7,000 cavalry), with 150 guns.

Joseph also commanded a small Spanish contingent.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Vitoria:

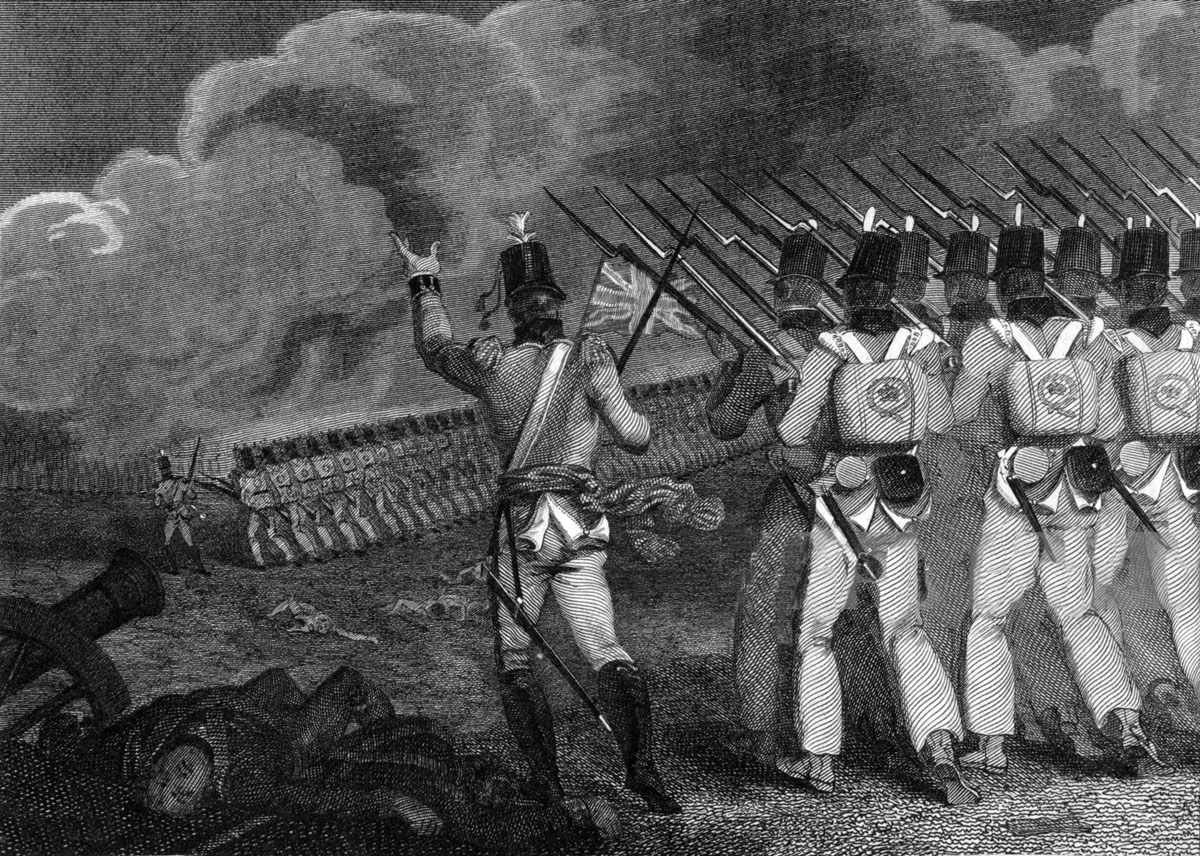

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers, and stovepipe shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments wore dark green jackets and trousers.

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

Highland regiments wore the kilt with red tunics and black ostrich feather caps.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and black fore and aft cocked hats. The change in uniform brought in during 1812 saw the British heavy cavalry adopt ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light dragoons wore light blue uniform coats and a leather helmet with a fur crest running front to back.

In 1807, the British 7th, 10th, 15th and 18th Light Dragoons were converted to Hussar Regiments of Light Cavalry and adopted the standard Europe-wide Hussar uniform, comprising a frogged tunic, dolman jacket hanging from the shoulder, tall fur busby cap, tight britches, heeled boots, moustaches and a curved sword.

The King’s German Legion (KGL) was formed largely from the old disbanded Hanoverian army. The KGL owed its allegiance to King George III of Great Britain, as the Elector of Hanover and fought with the British army. The KGL comprised both cavalry and infantry regiments. KGL uniforms followed the British.

The Portuguese army uniforms increasingly during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

The Spanish army was essentially without uniforms, existing as it did in a country dominated by the French. Where formal uniforms could be obtained, they were white.

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform coat was dark blue.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green and wearing crested helmets, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry, the horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket. The musket could be fired three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for a hundred metres or so. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, fitting into the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire and a sword bayonet.

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who invented it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was unable to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create his powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns with the speed of the French columns of infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

Winner of the Battle of Vitoria: The British, Portuguese and Spanish.

British order of battle at the Battle of Vitoria:

Commander: Lieutenant General (local General) the Marquess of Wellington

Officers of the Royal Horse Guards in Spain: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Denis Dighton

Right Column: commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Rowland Hill

Cavalry:

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Victor von Alten: 14th Light Dragoons and 1st Hussars, King’s German Legion

2nd Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant General Fane: 3rd Dragoon Guards and 1st Royal Dragoons

Infantry:

Second Division: commanded by Lieutenant General William Stewart

1st Brigade: commanded by Colonel Cadogan: 1st/50th, 1st/71st 1st/91st Foot and 1 company of 5th/60th Foot

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Byng: 1st/3rd, 1st/57th Foot, 1st Provisional Battalion (2nd/31st and 2nd/66th Foot) and 1 company of 5th/60th Foot

3rd Brigade: commanded by Colonel O’Callaghan: 1st/28th, 2nd/34th, 1st/39th Foot and 1 company of 5th/60th Foot

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Ashworth: 1stand 2nd/6th, 1stand 2nd/18th Portuguese Line and 6th Caçadores

Portuguese Division: commanded by Major General Silveira, Conde de Amaranthe

1st Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General de Costa: 1st and 2nd/2nd, 1st and 2nd/14th Portuguese Line

2nd Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Archibald Campbell: 1st and 2nd/4th, 1st and 2nd/10th Portuguese Line and 10th Caçadores

Spanish Division: commanded by Major General Morillo

Artillery: commanded by Major Carncross

Beane’s Troop Royal Horse Artillery

Maxwell’s Battery Royal Artillery

2 Portuguese batteries under Major Tulloh

Right Centre Column: commanded by the Marquess of Wellington

Cavalry

1st Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Sir Robert Hill: 1st and 2nd Life Guards and Royal Horse Guards

2nd Brigade: commanded by Colonel Colquohon Grant: 10th, 15th and 18th Light Dragoons (Hussars)

3rd Brigade: commanded by Major General William Ponsonby: 5th Dragoon Guards, 3rd and 4th Dragoons

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General D’Urban: 1st, 11th and 12th Portuguese Dragoons

Infantry:

Fourth Division: commanded by Major General (local Lieutenant General) Lowry Cole

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General William Anson: 3rd/27th, 1st/40th, 1st/48th, Provisional Battn. (1st and 2nd/53rd Foot) and 1 company of 5th/60th Foot

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Skerrett: 1st/7th, 20th, 1st/23rd, and 1 company of Brunswick Oels

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Colonel George Stubbs: 1st and 2nd/11th and 1st and 2nd/23rd Portuguese Line and 7th Caçadores

Light Division: commanded by Lieutenant General Charles, Baron von Alten.

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Kempt: 1st/43rd Foot, 1st/95th Rifles (8 Cos), 3rd/95th Rifles (5 companies) and 3rd Caçadores

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General John Ormesby Vandeleur: 1st/52nd Foot, 2nd/95th Rifles (6 companies) and 1st Caçadores

Artillery: commanded by Major Augustus Simon Frazer

Ross’s, Gardiner’s and Ramsay’s Troops, Royal Horse Artillery

Sympher’s Battery, King’s German Artillery

28. Podcast of the Battle of Vitoria: Wellington’s decisive defeat of Joseph Bonaparte’s French army on 21st June 1813 in North-Eastern Spain in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

28. Podcast of the Battle of Vitoria: Wellington’s decisive defeat of Joseph Bonaparte’s French army on 21st June 1813 in North-Eastern Spain in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

Left Centre Column: commanded by Lieutenant General the Earl of Dalhousie

Infantry:

Third Division: commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Picton

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Thomas Brisbane: 1st/45th, 74th, 1st/88th and 3 companies of 5th/60th Foot

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Colville: 1st/5th, 2nd/83rd, 2nd/87th and 94th Foot

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Major General Manley Power: 1st and 2nd/9th, 1st and 2nd/21st Portuguese Line and 11th Caçadores

Seventh Division: commanded by Lieutenant General Lord Dalhousie

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Barnes: 1st/6th Foot, 3rd Provisional Battalion (2nd/24th and 2nd/58th Foot), Brunswick Oels (7 companies)

2nd Brigade: commanded by Colonel William Grant: 51st, 68th, 1st/82nd Foot and Chasseurs Britanniques

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Major General Le Cor: 1st and 2nd/7th, 1st and 2nd/19th Portuguese Line and 2nd Caçadores

Artillery: commanded by Major Buckner

Batteries of Cairnes and Douglas

1st Foot Guards: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 in the Peninsular War: picture by Hamilton Smith

Left Column: commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Graham

Cavalry:

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General George Anson: 12th and 16th Light Dragoons

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Baron Bock: 1st and 2nd Dragoons, King’s German Legion

Infantry:

First Division: commanded by Major General Kenneth Howard

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Kenneth Stopford: 1st/Coldstream Guards, 1st/3rd Guards, and 1 company of 5th/60th Foot

2nd Brigade: commanded by Colonel Collin Halkett: 1st, 2nd and 5th Line Battalions, 1st and 2nd Light Battalions, King’s German Legion

Fifth Division: commanded by Major General Oswald

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Hay: 3rd/1st, 1st/9th, 1st/38th Foot and 1 company of Brunswick Oels

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Robinson: 1st/4th, 2nd/47th, 2nd/59th Foot and 1 company of Brunswick Oels

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Spry: 1st and 2nd/3rd, 1st and 2nd/15th Portuguese Line and 8th Caçadores

Independent Portuguese Brigades:

1st Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Pack: 1st and 2nd/1st, 1st and 2nd/16th Portuguese Line and 4th Caçadores

2nd Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Bradford: 1st and 2nd/13th, 1st and 2nd/24th Portuguese Line and 5th Caçadores

Spanish troops on the march: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Cristoph and Cornelius Suhl

Spanish Division: commanded by Colonel Francisco Longa

Artillery:

Dubordieu’s and Lawson’s batteries Royal Artillery

Army Artillery: commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Dickson

Webber Smith’s troop Royal Horse Artillery

Parker’s battery Royal Artillery

Arriaga’s battery Portuguese Artillery

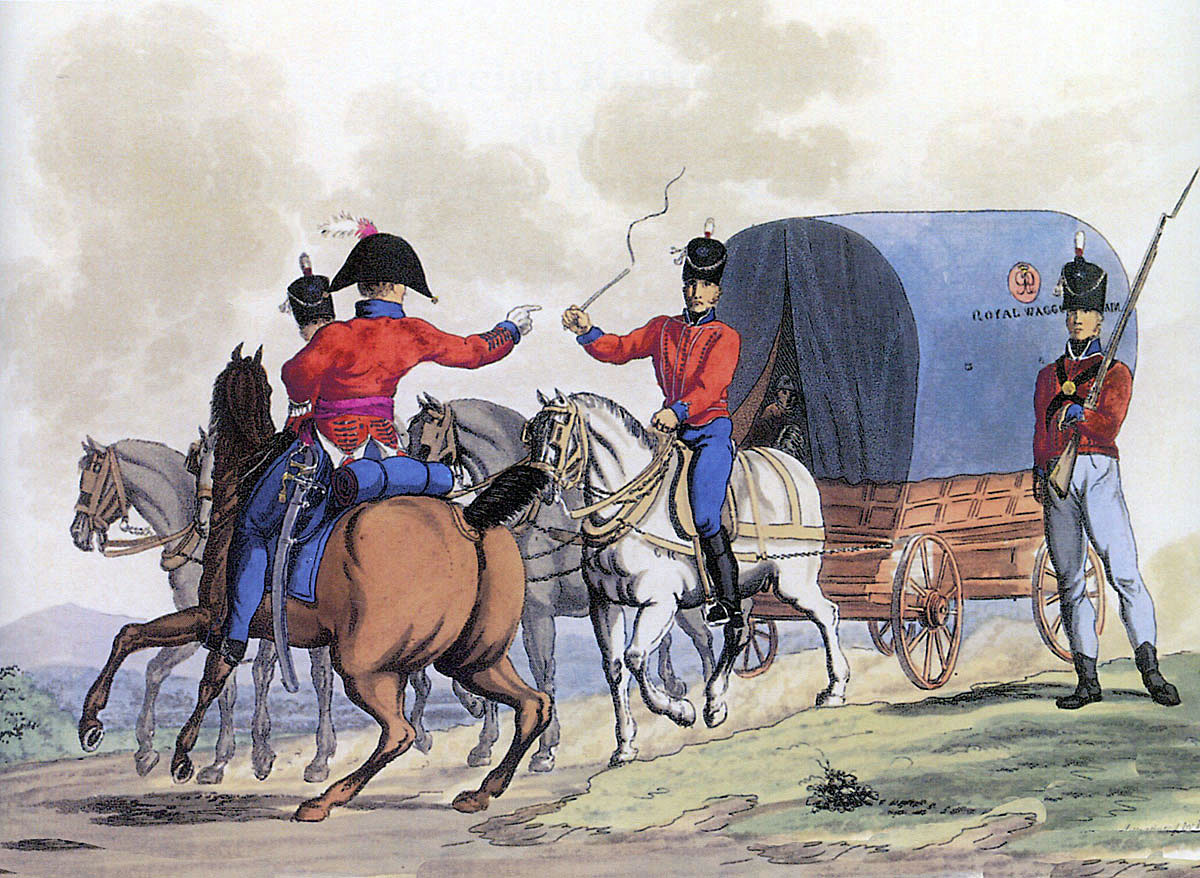

Royal Wagon Train: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Charles Hamilton Smith

French order of battle at the Battle of Vitoria:

Commander in Chief: Prince Joseph Napoleon, King of Spain

Chief of Staff: Marshal Jean Baptiste Jourdan

Army of the South: commanded by General Gazan

Cavalry:

1st Light Cavalry Division: commanded by General Soult

1st Division of Dragoons: commanded by General Tilly

Infantry:

1st Division: commanded by General Leval

3rd Division: commanded by General Villatte

4th Division: commanded by General Conroux

5th Division: commanded by General Maransin

6th Division: commanded by General Daricau

French Cavalry: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Cristoph and Cornelius Suhl

Army of the Centre: commanded by General Count D’Erlon

Cavalry:

Division of Dragoons: commanded by General Treilhard

Light Cavalry Brigade: commanded by General Avy

Infantry:

1st Division: commanded by General D’Armignac

2nd Division: commanded by General Cassagne

Artillery

Army of Portugal: commanded by General Reille

Cavalry

2nd Division of Dragoons: commanded by General Digeon

Division of Dragoons: commanded by General Mermet

Division of Light Cavalry: commanded by General Curto

Infantry:

Division: commanded by General Sarrut

Division: commanded by General Lamartinière

King Joseph’s Spanish Army:

Guard (Cavalry and Infantry)

Background to the Battle of Vitoria:

Lord Wellington began the 1812 campaign, the year before the Battle of Vitoria, by capturing the two cities on the Portuguese border that were key to driving the French from Spain; Ciudad Rodrigo on 19th January 1812 and Badajoz on 6th April 1812.

In May 1812, the Emperor Napoleon began the preparations for his fateful invasion of Russia, leaving his brother, King Joseph, in nominal command of the French armies in Spain.

French Infantry: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Cristoph and Cornelius Suhl

Napoleon told his brother that Wellington would remain on the defensive for the rest of 1812. Napoleon was wrong.

Following his capture of Badajoz, Wellington brought his army back to Ciudad Rodrigo and began an advance north-east up the main road leading to Salamanca, Burgos and the North-East of Spain.

On 22nd July 1812, Wellington heavily defeated Marshal Marmont’s Army of Portugal at the Battle of Salamanca.

Following Salamanca, on 12th August 1812, Wellington occupied Madrid, the Spanish capital, driving Joseph into a hurried retreat to the east with his army and the Spanish rash enough to support him.

In September 1812, Wellington resumed his advance up the main road, arriving before Burgos and beginning his attack on Burgos Castle on 19th September 1812.

The attack was unsuccessful, forcing Wellington to spend the rest of 1812 in a fighting retreat back to Ciudad Rodrigo.

The French hope was that Wellington would be unable to resume the offensive for some time, leaving the French armies across Spain to deal conclusively with the Spanish insurrections that were such a drain on their resources.

Wellington spent the winter of 1812/13 re-organising his forces and bringing in re-inforcements from Britain. He also meticulously planned his 1813 offensive against the French.

Joseph and his chief of staff, Marshal Jourdan, were advised by all the French generals with knowledge of the country, that if Wellington was to advance in 1813, he would be forced to use the well-trodden route from Ciudad Rodrigo to Salamanca, Valladolid and Burgos. The French needed only to repeat their strategy of the previous year and hold that road to bring Wellington to a halt, as they had in 1812.

Jourdan suspected that Wellington would not use the Burgos road but outflank the French armies by advancing from the north-eastern Portuguese border around their north-western flank.

Jourdan was nearly alone in this fear. The other French commanders asserted that the mountains to the north-west were impassable to an army with artillery. But this was exactly Wellington’s plan.

Wellington’s army of British, Portuguese and Spanish troops assembled in the area between Ciudad Rodrigo in the south and northern Portugal and began its advance in May 1813, the right flank of the advance being initially on the road to Salamanca.

The difficulties of the French armies were substantial. Napoleon was draining away drafts of experienced veterans from the regiments in Spain to re-build the French army destroyed in the Russian campaign.

Clausel was operating against Spanish insurrectionists in Navarre in the north-east of Spain, with a significant part of the ‘Army of Portugal’.

As throughout the Peninsular War, the French commanders were unable to obtain reliable information on Wellington’s movements or even communicate effectively with each other, due to the operations of the all-pervasive Spanish guerrillas, while Wellington was well informed on French movements by the same guerillas.

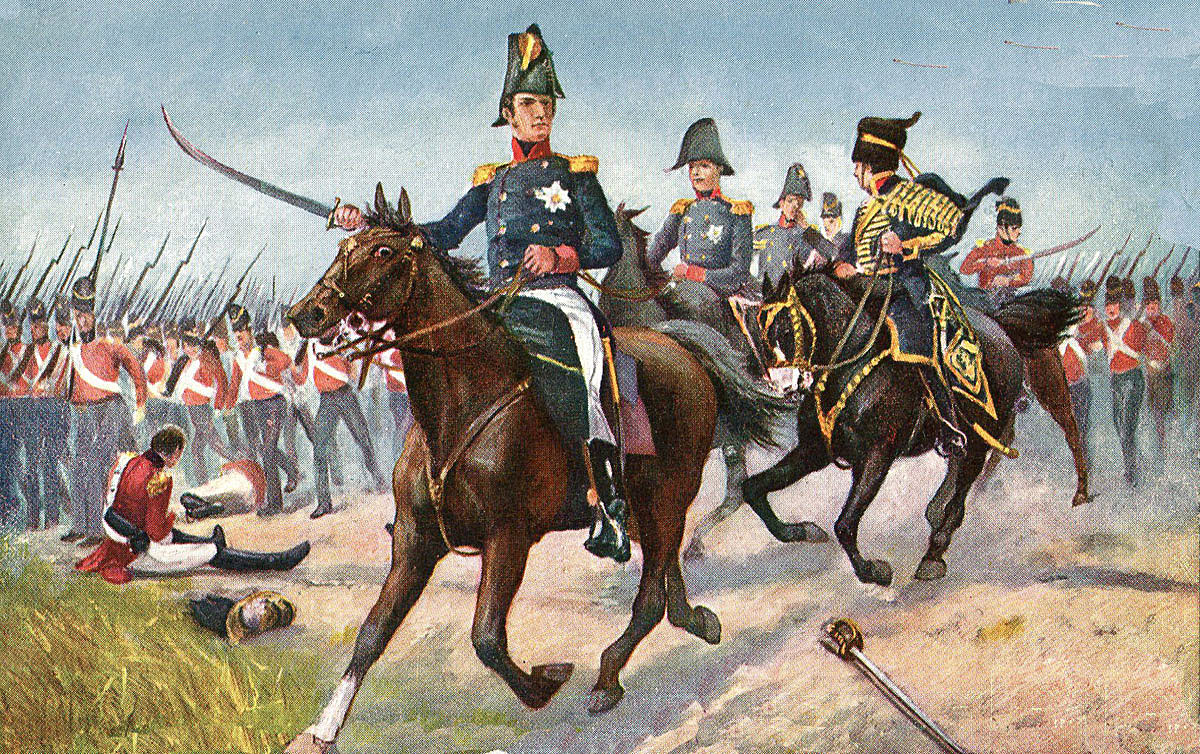

Wellington directing the attack by the Fourth Division at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War

Wellington’s army was supported by an extensive and efficient commissariat, which made the advance across the barren mountainous region of the north-west of Spain possible, although demanding.

As Wellington advanced, his army’s base of supply was moved from Lisbon in Portugal to Santander in the north-east of Spain.

Difficulties with communications through the guerrilla-infested country impeded Joseph in concentrating his forces to meet the threat from Wellington’s army.

With Madrid no longer tenable, Joseph dispatched two substantial convoys of valuables and money to the north-east of Spain. These convoys reached Vitoria and it was there that Joseph was forced to confront Wellington’s army.

On 30th May 1813, British divisions crossed the River Esla and joined their comrades crossing the River Douro.

Wellington’s army, now united, turned east and began the march in behind the French right flank, fighting, on 18th June 1813, the Battle of San Millan and Osma against General Reille.

Three French armies; the Army of the South, the Army of the Centre and the Army of Portugal, were concentrating at Vitoria, where they awaited General Clausel and his Army of the North (formed from divisions of the Army of Portugal). Clausel arrived the day after the Battle of Vitoria.

Lord Wellington at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by George Jones

Vitoria lies at the eastern end of a rectangular plain stretching from east to west. The main road to France heads north-east across the plain. The Madrid road runs to the south-west. Forming a cross-roads with these roads are the north-south roads to Bilbao.

The River Zadorra flows along the northern boundary of the plain and makes a wide curve to the south, leaving the plain at its south-western corner through a narrow defile at La Puebla.

The foothills of the Pyrenees Mountains surround the plain.

The River Zadorra was described by French officers who reconnoitred it as ‘shallow and fordable at all points’. This was partially true, but the river banks were steep and high in many places making access difficult and the river was dammed for the use of several mills, creating wide, deep lagoons.

Several bridges crossed the Zadorra.

The French army gathered at Vitoria from 20th June 1813 suffered significant handicaps. Its soldiers were imbued with the fighting spirit, training and experience of the French armies of the time, but it lacked a strong central command.

Three separate French armies were present at Vitoria; armies that had operated for years in different areas of Spain, under commanders only reluctantly acknowledging the authority of Joseph.

While Joseph’s chief of staff, Marshal Jourdan, was a prominent French soldier, he was not a commander and consequently lacked authority.

Preparations for the Battle of Vitoria:

On the night of 18th June 1813, Wellington’s army lay along the north-west to south-east road between Mambliga and Espejo, some 20 miles to the west of Vitoria, with Reille’s 3 divisions of the Army of Portugal around Salinas de Anaña, a few miles away. The rest of Joseph’s army lay further south, marching towards Vitoria.

Only at this time did Joseph and his chief of staff, Marshal Jourdan, finally resolve that a stand must be made in the Vitoria plain. The decision was influenced by the need to cover the substantial convoys of valuables, cash and official documentation either in Vitoria or heading there and the danger to Clausel’s Army of the North (drawn from the Army of Portugal) expected in Vitoria from the north-east.

Reille was ordered to fall back on Subijana de Morillas on the River Bayas, resisting the advance of Wellington’s columns as he did so, to enable Joseph’s troops to cross the Bayas and reach Vitoria before being cut off by Wellington’s advance.

Reille carried out this order, enabling the divisions of D’Erlon and Gazan to cross the River Zadorra, before he was forced back.

On the night of the 19th June 1813, Wellington’s divisions encamped along the River Bayas.

Jourdan was unsure what Wellington was planning. Reports were coming in of activity from the direction of Bilbao and Jourdan could not rule out the prospect of an attack on Vitoria from the north rather than the west.

With the decision to make a stand around Vitoria, Joseph and Jourdan were putting their trust in the arrival of General Clausel, who, after receiving Joseph’s summons to join his army at Burgos, was marching south-west from Pamplona with ample supplies, Taupin’s and Barbot’s divisions of the Army of Portugal and Abbé’s and Vandermaesen’s divisions of the Army of the North, some 12,000 men in all.

While Clausel was unaware that Joseph and his army had been forced into headlong retreat up the Burgos road, his journey to Burgos should take him through Vitoria, where he would meet Joseph’s army.

The question was whether Clausel would arrive in time for the battle with Wellington, in which case his additional troops could well tip the scales in favour of Joseph. In the event Clausel did not arrive in time.

General Foy was operating towards Bilbao, when he received Joseph’s instructions to bring his division to join the army at Vitoria. Foy’s commitments in relation to Bilbao and the French convoys passing through the city prevented him from immediately obeying Joseph’s instruction and his division also missed the battle.

French positions in the plain of Vitoria on 20th June 1813:

As the French army marched into the Vitoria plain it took up defensive positions behind the River Zadorra.

The Army of the South, 22,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry and 50 guns, positioned itself furthest to the west, becoming the inevitable target for Wellington’s opening assaults.

In the south-west corner of the Vitoria plain, a single French brigade, Maransin’s, occupied the village of Subijana, with troops on the extensive and lofty Puebla Heights south of the village.

3 further divisions of the Army of the South formed a line along the hills from south to north behind the western arm of the River Zadorra, overlooking the village of Nanclares on the far bank: Conroux’s, Darricau’s and Leval’s: Each division with a battery of artillery posted to its front.

British Hussar Brigade attacks Sarrut’s Division at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by John Augustus Atkinson

To the right rear of these divisions, the division of Villatte occupied the knoll of Ariñez with 3 field batteries.

Of the three divisions of cavalry of the Army of the South, Soult’s light cavalry was at Ariñez, Tilly’s dragoons at Ali, some 5 miles to the rear of the infantry and Digeon’s dragoons at Arriaga, on the River Zadorra immediately north of Vitoria.

The Army of the Centre, 9,000 infantry, 1,000 cavalry and 14 guns, occupied the heights to the west of the village of Gomecha, behind the Army of the South and in the centre of the Vitoria plain: D’Armagnac’s division to the north of the main west-east road and Cassagne’s division to the south of the road.

Joseph’s Spanish contingent was far in the rear, on the road to Salinas, north-east of Vitoria.

British Hussar Brigade repels Digeon’s Division at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by John Augustus Atkinson

The cavalry of the Army of the Centre, Treilhard’s dragoons and Avy’s light cavalry, were in the rear.

The Army of Portugal, 11,000 infantry, 1,200 cavalry and 42 guns, was positioned with much of its infantry, the divisions of Lamartinière, Maucune and Sarrut, each with a battery, some 4 miles immediately behind the Army of the South, between the villages of Ali and Armentia.

The cavalry of the Army of Portugal lay along the northern arm of the River Zadorra between Gobeo and Margarita, guarding the various fords and bridges and the area to the north of the river.

25 of the guns of the Army of Portugal were in the artillery reserve held in Vitoria with the reserve of the Army of the Centre.

French artillery at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Dalmau

The position on 20th June 1813:

Joseph and Jourdan intended to conduct a review of the French positions on 20th June 1813 and make a final decision as to their deployment for the battle.

There was little time as Wellington’s army lay nearby, behind Subijana on the River Bayas, 6 miles west of the River Zadorra at Nanclares and was clearly resting from the exertions of its march, before attacking the French.

The restriction on Joseph’s freedom of choice was the vast accumulation of stores, treasure and records of government at Vitoria. A large convoy left for the French border on 19th June 1813, still leaving much to dispose of.

Jourdan was ill on 20th June 1813 and the review put off to the next day; a fatal postponement.

Jourdan’s continuing apprehension was that Wellington intended to advance on Bilbao and attack the French armies at Vitoria from the north.

An infantry brigade from the Army of Portugal, supported by a brigade of dragoons was dispatched up the northern road towards Murguia. The French troops were stopped by the Spanish force commanded by Longa and driven back.

This encounter confirmed Jourdan in his suspicion that this was the true direction of Wellington’s attack on Vitoria and he ordered Sarrut’s division across the River Zadorra by the Ariaga bridge, with orders to hold the road at Aranguiz.

Arriving on the River Bayas on 20th June 1813, Wellington’s troops needed the day to recover from the arduous march from the Portuguese border. Wellington also needed to prepare his dispositions for the attack on the French.

British 6 pounder cannon in action: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 in the Peninsular War: Firepower Museum

Graham and Giron were ordered to occupy Murugia, on the far left wing of the army.

The British Third and Seventh Divisions crossed the River Bayas and prepared to launch the main attack from the west.

The Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813:

At 1am on 21st June 1813, Sarrut’s Division crossed the River Zadorra and took up position at the village of Aranguiz, supported by a battery of artillery and a brigade of light cavalry from Curto’s division.

At 3am, Joseph’s second large convoy left Vitoria for Bayonne, escorted by Maucune’s Division, thereby reducing his army by around 4,000 men.

Soon afterwards, at around 5am, Joseph and Jourdan began the reconnaissance postponed from the previous day. They began their inspection at the village of Zuazo, 3 miles west of Vitoria.

Joseph and Jourdan were favourably impressed by the defensive potential at Zuazo; a position on raised ground, giving a good field of fire for guns, with a mountain on its left flank and the River Zadorra on the right and near to Aranguiz, the point beyond the river threatened by the impending British advance from the direction of Bilbao.

Officer and soldier of the 71st Highland Light Infantry: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Joseph and Jourdan were considering bringing back the divisions positioned further forward overlooking the western arm of the River Zadorra, when they received warning from Gazan, the commander of the Army of the South, that Wellington’s troops were on the move. It was too late to make any re-disposition.

At around 8am, the outposts of Maransin’s Division situated on the Puebla Heights sent word that two British and Spanish columns had crossed the River Zadorra at Puebla. One column, comprising Morillo’s Spanish troops was scaling the Puebla Heights and the other, comprising the main body of Hill’s Second Division was advancing up the main Burgos road toward Vitoria.

The flanking threat on the Puebla Heights was of great concern to Jourdan, who ordered Gazan to send the whole of Maransin’s Division onto the heights and to support him with an additional division. 5 batteries were ordered forward from the Army of Portugal’s reserve at Vitoria to support Gazan and D’Erlon.

British infantry at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Additional news came in from Avy, with his light cavalry division on the northern bank of the River Zadorra, that a strong column of British troops was advancing south towards Tres Puentes.

Jourdan ordered D’Erlon to send D’Armagnac’s Division to defend the Tres Puentes crossings, accompanied by the cavalry of the Army of the Centre, Treilhard’s Dragoon Division and the rest of Avy’s Light Cavalry Division.

On the French left flank, Morillo’s Spanish troops reached the summit of the Puebla Heights, where they engaged Maransin’s troops.

Hill re-inforced Morillo with the 71st Highland Light Infantry and the light companies of Walker’s Brigade. Slowly the French were driven back up the hillside.

In the meantime, Wellington was holding up his planned attack elsewhere on the battlefield, because Dalhousie’s left centre column, allotted the task of attacking across the northern arm of the River Zadorra east of Tres Puentes, had lost its way during the approach march and failed to appear.

British troops were massed around Nanclares, awaiting events, with a party making its way up the River Zadorra to Villodas.

While Gazan considered Morillo’s advance up the Puebla Heights to be a feint, Jourdan was considerably disturbed by the attack, taking the opposite view to Gazan and considering the advance towards the northern arm of the River Zadorra to be the feint.

None of Wellington’s attacks were feints. They were all full assaults on the various French armies.

Joseph followed Jourdan ’s urgings that the Puebla Heights must be retaken. Cassagne’s infantry division was moved to the village of Berrostequieta at the eastern end of the heights with Tilly’s dragoon division, while Vilatte’s infantry division was ordered onto the heights via Zumelu, to sweep along the crest to the west and drive back the Spanish and British attack.

Hill was now advancing up the main Burgos road.

71st Highland Light Infantry at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

Hill sent the 50th and 92nd Regiments of Callaghan’s brigade to support the 71st, while the rest of the brigade attacked Subijana, where a lengthy struggle took place in the village and the surrounding woods.

Drummer 92nd Highlanders: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

The position of the 71st and the Spanish troops on the Puebla heights was threatened by the attack of Villatte’s Division.

Colonel Cameron, now commanding all 3 British regiments, the 50th, 71st and 92nd, on the heights, required his men to sit down, out of sight, until the French were within 30 yards. The British troops stood up and delivered a volley that sent Villatte’s men rushing back across the mountainside.

Vilatte’s men re-formed for a further attack, but became increasingly unsure, as they saw the developments in the open ground to their north, until finally no advance was made.

While these attacks were taking place, the other formations of Wellington’s army were finally beginning their advance.

The Light Division and the Hussar Brigade, directed by Wellington himself, marched up the River Zadorra from Nanclares and formed for the attack, concealed from the French on the far side of the river by the thick banks of scrub.

Cole’s column formed up behind Nanclares.

Picton’s Third Division formed at Mendoza, to the north of the bend in the River Zadorra.

Wellington only awaited the arrival of the balance of Lord Dalhousie’s Seventh Division at the northern end of the line, to begin the attack.

While Dalhousie’s first brigade was in place, the main part of his Seventh Division lost its way during the approach march over the mountains, holding up Wellington’s plan, while he waited for the missing formation.

15th King’s Light Dragoons (15th Hussars) crossing the bridge at Tres Puentes in the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Soldiers from the 95th Rifles engaged French skirmishers across the river while they waited.

A Spanish peasant approached some British officers and informed them that there was a bridge at Tres Puentes unoccupied by the French.

The peasant’s offer to conduct the British to the bridge was accepted and Kempt’s Brigade of the Light Division, led by the 1st/95th Rifles, set off. Kempt’s Brigade took a path leading back into the mountains, to conceal their move.

Arriving at the bridge, Kempt’s Brigade doubled across and climbed into the hills on the south bank. Led by Colonel Barnard, the 1st/95th halted in a hollow, within a short distance of D’Armagnac’s Division, at that moment accompanied by Joseph Bonaparte.

Colonel Andrew Barnard, commanding 1st/95th Rifles at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War

Shortly afterwards, Kempt summoned the 15th Hussars across the bridge in support of his brigade.

Avy’s Division of French Light Cavalry was still on the north bank of the River Zadorra, to the north of Tres Puentes. A party of troops from Avy’s Division rode down to the bridge and were subjected to fire by Kempt’s men on the far bank.

D’Erlon heard from Avy that British troops were across the River Zadorra at Tres Puentes and hurried to the scene, to find that Joseph and Jourdan, unaware of the threat to their position, were about to dispatch the divisions of D’Armagnac and Cassandre to counter-attack Hill in his advance up the Burgos road.

On hearing D’Erlon’s information, Joseph and Jourdan were amazed to find the position of the Army of the Centre so badly compromised, without any of its senior officers being aware of the British incursion across the river at Tres Puentes.

Further to the south, Hill was now in possession of the village of Subijana, enabling Wellington to order an attack across the River Zadorra by Picton’s Third Division (part of Dalhousie’s Left Centre Column) and Cole’s Fourth Division (part of Wellington’s Right Centre Column).

Picton advanced to the bridge across the River Zadorra at Mendoza, a half mile east of Tres Puentes.

Picton’s men were resisted by French skirmishers and a battery of guns. Hearing the burst of firing, Colonel Barnard’s 95th Rifles left its position on the southern bank overlooking the Tres Puentes bridge and drove off the French troops and guns blocking Picton’s advance.

Picton’s two brigades crossed the river by the bridge and a ford and formed in columns on the southern bank.

Dalhousie finally arrived at the Mendoza Bridge and crossed the river.

The Fourth Division also crossed to the French bank, by way of the bridge at Nanclares.

Lord Wellington at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Thomas Jones Barker

With the line of the River Zadorra taken by Wellington’s divisions, Jourdan ordered a French withdrawal step by step, back to the heights of Zuazo, by the divisions of the left wing; Maransin’s, Villatte’s, Conroux’s and Darricau’s.

To enable these divisions to withdraw, Gazan ordered Leval’s Division to the knoll of Ariñez, while D’Erlon led the divisions of D’Armagnac and Cassagne to Margarita. In addition, some 60 guns were massed in the area of the knoll to give the left wing the best chance of withdrawing to the Zuazo position.

As Wellington’s attack on the knoll of Ariñez was developing, cannon fire could be heard from the far end of the battlefield with a pall of smoke, indicating that Graham, acting on his own initiative, was opening an assault on the French right flank beyond Vitoria.

Dalhousie and Colville’s Brigades of Picton’s Division attacked D’Erlon around Margarita and Lermanda, while Kempt and Brisbane’s Brigades attacked the knoll of Ariñez.

A hard-fought struggle took place in and around the village of Ariñez, with Picton leading the assault and Wellington supervising from a position further back.

Wellington himself halted the 88th and 74th Regiments and re-formed them, before permitting them to continue with their attack on the village.

Major Dickson, commanding the British artillery, brought the guns up the main Burgos road and formed them up to deliver a substantial bombardment on Leval’s division.

95th Rifles storming the village of Margarita in the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by WAS Stott

The French were forced back and a mounted battery lost 3 of its guns in retreating through the village.

Substantial casualties were suffered by each side, but particularly by the British at the hands of the French skirmishers.

Leval pulled his division and its accompanying artillery back, contesting the ground all the way, to a position at the northern end of Gazan’s line based on Zuazo.

As Leval fell back, he left D’Erlon flank exposed. D’Erlon’s divisions until this point were resisting the advance of Colville’s Brigade.

Dalhousie seems to have allowed his attention to shift from D’Erlon to the attack on Ariñez, leaving Colville to engage D’Erlon’s divisions alone.

Seizing an opportunity, Vandeleur’s Brigade of the Light Divisions (1st and 2nd/95th Rifles and 52nd Regiments) stormed Margarita, with Dalhousie’s 2nd Brigade in support.

Shortly afterwards, Colonel Gough led his 87th Regiment in the capture of Lermanda.

D’Erlon was well into his withdrawal by now, taking up positions that extended Gazan’s Zuazo line to the River Zadorra at Crispiana, with Treilhard’s and Avy’s cavalry divisions behind him.

Along Wellington’s line his divisions were coming up in pursuit of the withdrawing French.

Wellington at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by R. Granville Baker

Graham’s attack on the French Right Wing:

The French right wing, held by Reille’s Army of Portugal, lay to the north-east of Vitoria, on the eastern section of the River Zadorra, some 7 miles from the area where Wellington was assaulting the Armies of the Centre and the South.

Graham began his attack on the Army of Portugal at 2pm, on his own initiative.

Two columns of infantry and one of cavalry advanced on Sarrut’s Division, positioned north of the Ariaga Bridge, causing the French to fall back towards the bridge.

Reille, informed of the British movement to the north of the River Zadorra, moved Lamartiniere’s Division to the bridge at Gamarra, immediately to the east of the Ariaga bridge.

Graham sent Longa’s Spanish Division to tackle the Gamarra bridge and the next bridge to the east, at Durana, held by Joseph’s Spanish troops, who immediately abandoned their position, leaving Longa free to cross the River Zadorra and move on Reille’s right flank, a step Longa failed to take, remaining at the bridge for the rest of the battle.

Reille reacted to the threat from Graham’s columns with a number of dispositions.

Menne’s Brigade of Sarrut’s Division in Abechuco covered the bridge at Arriaga.

Lamartiniere’s Division held Gamarra Mayor, with Fririon’s Brigade of Sarrut’s Division positioned between Abechuco and Arriaga to provide support for both formations.

Of the cavalry, Digeon’s Division of Dragoons supported the French in Arriaga and Mermet’s Division of Dragoons supported Gamarra Mayor.

A brigade of Curto’s Light Cavalry covered the River Zadorra between Arriaga and Gobeo.

4th, 47th and 69th Regiments storming Gamarra Mayor at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 in the Peninsular War: picture by JP Beadle

General Oswald now launched Robinson’s Brigade of the Fifth Division (1st/4th, 2nd/47th, 2nd/59th Regiments) in an attack on Gamarra Mayor.

These British regiments were caught by a blast of fire from a battery on their flank and thrown into confusion.

The attack was renewed and the brigade took Gamarra Mayor and stormed across the bridge, capturing a gun.

On the far bank, the three British regiments were caught in the fire of yet another French battery and driven back across the bridge by Lamartiniere’s troops.

A French officer reported after the battle that the opposing regiments charged each other, back and forth, on seven occasions.

General Oswald now sent forward Hay’s Brigade (3rd/1st, 1st/9th, 1st/38th Regiments) to take over the attack from Robinson’s.

Again, the British took the bridge and were again driven back by the French.

While the fighting was taking place around Gamarra Mayor, Graham launched a further attack on Abechuco. Preceded by a bombardment from two British batteries, Halkett’s two light battalions of the King’s German Legion stormed Abechuco, taking four French guns. No further advance towards the bridge at Arriaga was made.

The French withdrawal of their Centre and Left:

French 12th Dragoons: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Édouard Detaille

Wellington ordered the advance of the British and Portuguese troops against the French Army of the South, positioned behind Zuazo and D’Erlon’s divisions along the north arm of the River Zadorra, while the British and Spanish troops fought on the Puebla Heights with Maransin’s and Vilatte’s Divisions.

The British and Portuguese, advancing on the lower ground, suffered from the heavy artillery fire of the French guns in the extended Zuazo position.

D’Erlon stood fast in Crispijana, but as Wellington’s line advanced, Gazan’s Army of the South fell back from the Zuazo position towards Vitoria, leaving D’Erlon’s left flank badly exposed.

At around 5pm on 21st June 1813, Joseph made the decision that the battle was lost and sent orders to all the French generals in the field to disengage and retreat by the eastern road out of Vitoria towards Salvetierra.

Joseph sent General Tirlet to ensure that the guns and baggage in the park in Vitoria were evacuated.

In the meantime, Sarrut and Digeon attempted to hold the bridge at Arriaga, Digeon in vain sending messages to Vitoria calling for a single division and 12 guns to hold back Graham’s attack. No such reinforcements were forthcoming.

The Armies of the South and the Centre made a last stand on a line between the villages of Ali and Armentia, halting the advance of the Third Division, before beginning the final withdrawal through Vitoria.

British Hussars attack the French baggage train in the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War: picture by Henri Dupray

Fighting effectively until this point, the French divisions became unsteady in this final withdrawal.

The British Fourth Division launched an assault on the left of the French line which drove the French troops out of their positions in confusion.

On the British left, D’Erlon’s withdrawal left a gap, through which the British Hussar Brigade advanced and attacked the exposed left flank of Sarrut’s Division.

Digeon’s 5th and 12th Dragoon Regiments charged repeatedly, attempting to rescue Sarrut’s infantry, but were repelled.

On the French right flank, the British First Division crossed the bridge of Arriaga and the Fifth Division crossed the bridge at Gamarra.

Reille withdrew his brigades in succession, aided by Digeon’s dragoons.

Wellington’s army was now occupying most of the roads, forcing D’Erlon’s and Reille’s Divisions to retreat to the Salvetierra road across country, abandoning their guns.

Reille’s Army of Portugal finally rallied in Betoño, 3 miles north-east of Vitoria, at around 7 pm.

Top Hat worn by Sir Thomas Picton at the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War

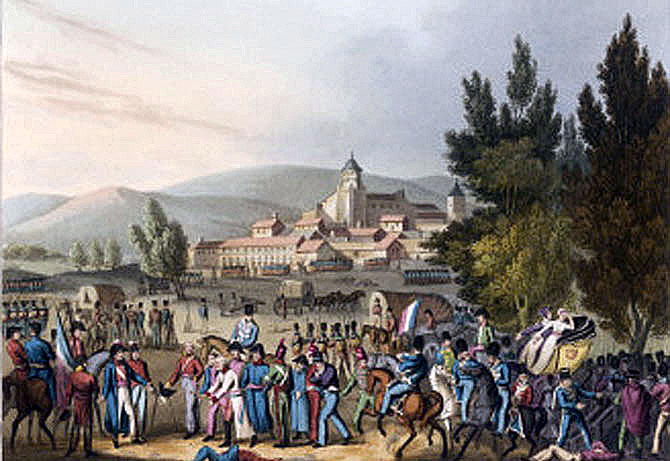

Wellington’s army enters Vitoria:

By 7.30pm on 21st June 1813, the British Hussar Brigade was in Vitoria and some regiments were looting and no longer available for combat.

Anson’s and Bock’s Brigades of cavalry, after crossing the bridge at Gamarra, were pursuing the French in the direction of Pamplona.

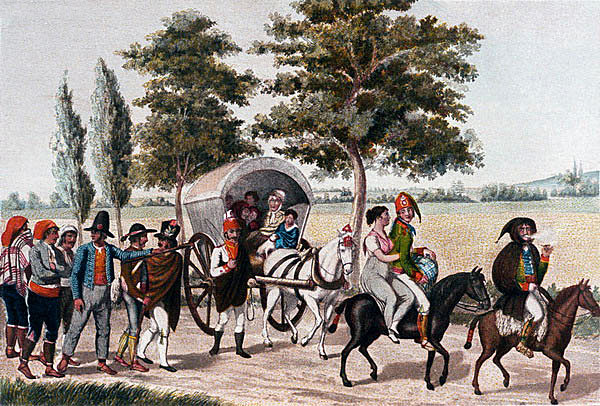

3,000 vehicles were crammed into the area of Vitoria, filled with goods being removed by Joseph’s army, together with herds of livestock. These were extensively looted by troops of all nationalities involved in the battle.

There were also crowds of civilians attempting to escape the collapse of the French regime in Spain. Joseph is said to have abandoned his coach and escaped on horseback from the British 18th Hussars.

Reille’s divisions continued east out of Betoño, evading or fighting off the pursuit and finally marched down the road towards Salvetierra.

Later that night, Joseph, Jourdan and the senior French officers gathered in Salvetierra to contemplate the approaching end of their dominance of Spain.

14th Light Dragoons capturing Joseph Bonaparte’s baggage: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War

Casualties at the Battle of Vitoria:

The British suffered 3,675 troops killed or wounded, the Portuguese 921 and the Spanish 562.

The French suffered 8,000 troops killed, wounded or captured and lost all their 150 guns, except one.

Soldier of the Royal Scots, 1st of Foot: Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War

British casualties were more than double the total of Portuguese and Spanish casualties.

Losses fell disproportionately on British regiments.

The 71st Highland Light Infantry, involved in the extensive fighting on the Puebla heights, lost 15 officers and 301 soldiers killed or wounded.

The other regiments in the same brigade (Cadogan’s) lost 104 casualties for the 50th and 20 for the 92nd.

In O’Callaghan’s Brigade of the Second Division, the 39th lost 209 of all ranks killed or wounded, the 28th lost 200 and the 34th lost 76.

In Brisbane’s Brigade of the Third Division, the 88th lost 215 of all ranks killed or wounded, the 74th lost 83 and the 55th lost 74.

In Colville’s Brigade of the Third Division, the 87th lost 187 of all ranks killed or wounded, the 5th lost 163, the 83rd lost 74 and the 94th lost 66.

In the Seventh Division, the 86th Regiment lost 125 of all ranks killed or wounded.

In the Fifth Division the Royal Scots lost 111 of all ranks killed or wounded, the 4th lost 91, the 47th lost 112 and the 59th lost 145.

The Fourth and Light Divisions had few casualties.

Several British and German brigades, including the two Brigades of Foot Guards, did not fire a shot in the battle.

Casualties in the cavalry regiments were few.

Joseph Napoleon escaping after the Battle of Vitoria on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War: picture by B. Granville Baker

Military General Service Medal 1848 with clasp for the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 in the Peninsular War

Follow-up to the Battle of Vitoria:

The battle was of wide significance throughout Europe. The Emperor Napoleon was already reeling from the catastrophe of the Russian campaign. Vitoria helped to show that his dominance of the continent was coming to an end. The battle established Lord Wellington’s reputation throughout Europe, as indicated by Beethoven’s tribute (see below).

On hearing the news of the battle, the Austrians mobilised and declared war on France. The Emperors of Russia and Austria both offered Lord Wellington command of their armies, which he declined.

Fortescue considers the battle to have been an unsatisfactory victory. He points out that the French suffered few casualties regiment by regiment. The French defeat is however marked by their loss of 150 guns and the loss of their baggage.

Fortescue’s judgement is that the British divisions were not well handled in the battle, with some regiments allowed to suffer heavy casualties while inadequately supported.

Fortescue questions why Wellington’s troops did not cross the shallow River Zadorra at more points. He asks why Graham failed to push his substantial force across the almost undefended bridge taken by Longa at Durana and attack Reille’s Army of Portugal in the flank.

Medal by Mills and Lefevre commemorating the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 in the Peninsular War

Battle Honours and Medals for the Battle of Vitoria:

Small Gold Medal awarded to Major Robert Kelly of 5th/60th Rifles for the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813 during the Peninsular War

The Battle of Vitoria is a clasp on the 1848 Military General Service Medal and a battle honour for the following British regiments: 3rd and 5th Dragoon Guards, 3rd Dragoons, 11th, 12th, 13th and 16th Light Dragoons, 10th, 15th and 18th Hussars, 1st Royals, 4th King’s Own, 5th, 7th Royal Fusiliers, 20th, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 27th, 28th, 31st, 34th, 38th, 39th, 40th, 43rd Light Infantry, 45th, 47th, 48th, 50th, 51st, 52nd Light Infantry, 53rd, 57th, 59th, 60th Rifles, 66th, 68th, 71st, 74th, 82nd, 83rd, 87th, 88th Connaught Rangers, 92nd, 94th and 95th Rifles.

Army Gold Medal:

In 1810 a Gold Medal was issued to be awarded to officers of rank of major and above for meritorious service at certain battles in the Peninsular War, with clasps for additional battles. The ‘Large Gold Medal’ was awarded to generals, the ‘Small Gold Medal’ to majors and colonels, with the medal replaced by a cross where four clasps were earned. The Battle of Vitoria was one of the battles.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Vitoria:

- One of the items looted from Joseph Bonaparte’s baggage was a silver chamber pot. The regiment that ‘liberated’ the pot, the 14th Light Dragoons (later 14th Hussars and now the King’s Royal Hussars), retained it as a trophy and, to this day, use it on regimental guest nights for the toasts, filled with champagne. The chamber pot is known as ‘the Emperor’.

- To commemorate the battle Beethoven wrote a symphony that he called ‘Wellington’s Victory’.

- One of the changes implemented in the British Army during the winter of 1812/13 was to give the senior sergeant in each infantry company the new rank of ‘colour sergeant’, with the regimental colours embroidered beneath his chevrons, while in the cavalry the senior sergeant in each troop was given the new rank of ‘troop sergeant major’.

- General Picton went into battle at Vitoria wearing his characteristic blue topcoat and top hat.

- The 1st/95th Rifles led Kempt’s Brigade across the River Zadorra at Tres Puentes. The hill the 95th mounted on the south bank was given the name of ‘Barnard’s Hill’, after the commanding officer of the battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Barnard.

- When Wellington’s army entered Vitoria General Ponsonby’s Brigade of Cavalry (5thDragoon Guards, 3rd and 4th Dragoons) rode past a pile of dollars lying in the street. No soldier attempted to touch them. General Ponsonby left a sergeant-major to gather as many of the coins as he could and a distribution was made of $5 to each of the 1,300 men in the brigade.

References for the Battle of Salamanca:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of San Millan and Osma

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Storming of San Sebastian

28. Podcast of the Battle of Vitoria: Wellington’s decisive defeat of Joseph Bonaparte’s French army on 21st June 1813 in North-Eastern Spain in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts