Sir Arthur Wellesley’s victory over the French army of Marshal Junot in Portugal on 21st August 1808, his first major victory in the Peninsular War, which nearly ruined his military career

Podcast of The Battle of Vimeiro: Sir Arthur Wellesley’s victory over the French army of Marshal Junot in Portugal on 21st August 1808, his first major victory in the Peninsular War, which nearly ruined his military career: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcasts.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Roliça

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Sahagun

Battle: Vimeiro

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of Vimeiro: 21st August 1808

Place of the Battle of Vimeiro: Central Portugal

Combatants at the Battle of Vimeiro: British and Portuguese against the French

Generals at the Battle of Vimeiro: Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Wellesley against Marshal Junot

Size of the armies at the Battle of Vimeiro:

The British Army comprised 500 British and Portuguese cavalry, 20,000 infantry and 18 guns.

The French Army comprised 1 cavalry division of 2,000 men, 5 infantry brigades of 12,000 men and 23 guns.

Winner of the Battle of Vimeiro: British and Portuguese

British order

of battle at the Battle of Vimeiro:

Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Wellesley

Cavalry: 20th Light Dragoons

First Brigade, Major General Hill: 1st/5th, 1/9th and 1st/38th Regiments

Second Brigade, Major General Ferguson: 36th, 1st/40th and 1st/71st Regiments

Third Brigade, Major General Nightingall: 29th and 1st/82nd Regiments

Fourth Brigade, Brigadier General Bowes: 1st/6th and 1st/32nd Regiments

Fifth Brigade, Brigadier General Catlin Craufurd: 1st/45th and 91st Regiments

Sixth Brigade, Brigadier General Fane: 1st/50th, 5th/60th and 4 Cos 2nd/95th Regiments

Seventh Brigade, Brigadier General Anstruther: 2nd/9th, 2nd/43rd, 2nd/52nd and 2nd/97th Regiments

Eighth Brigade, Major General Acland: 2nd, 7 Cos 20th and 2 Cos 1st/95th Regiments

Artillery: 18 guns (6 and 9

pounders) and 660 all ranks

Portuguese at the Battle of Vimeiro: Colonel Trant

Infantry 1,400

Cavalry 250

French order of battle at the Battle of Vimeiro:

Marshal Junot

Delaborde’s Division:

Brennier’s brigade: 3rd/2nd Light, 3rd/4th Light, 1st and 2nd/70th Line

Thomière’s brigade: 1st and 2nd/86th Line and 2 Cos 4th Swiss

Loison’s Division:

Solignac’s brigade: 3rd/12th Light, 3rd/15th Light and 3rd/58th Line

Charlot’s brigade: 3rd/32nd Light and 3/82nd Line

Reserve: 4 battalions of grenadier companies

Margaron’s Cavalry Division: 1st Provisional Chasseurs à Cheval, 3rd, 4th and 5th Provisional Dragoons and 1 Squadron Volunteers.

23 guns

Background to

the Battle of Vimeiro:

In July 1808 the British

government of the Duke of Portland sent a British army to Portugal, to assist

the Portuguese in their insurrection against Marshal Junot’s French army of

occupation.

The commander of this army, for the time being and in the absence of the more senior commanders, was Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Wellesley (later to become the Duke of Wellington).

Wellesley’s army arrived by sea at the Portuguese city of Oporto on 24th July 1808, where he consulted with the Supreme Junta of Portugal.

Wellesley received news that a British naval squadron had secured the area of Mondego Bay, providing a landing point for Wellesley’s troops in the southern half of Portugal, from which he could march on the Portuguese capital, Lisbon.

Podcast of The Battle of Vimeiro: Sir Arthur Wellesley’s victory over the French army of Marshal Junot in Portugal on 21st August 1808, his first major victory in the Peninsular War, which nearly ruined his military career: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcasts.

Sir John Moore was at Corunna, in north-west Spain and had reasonable expectations that he would be given command of the British troops assembling on the west coast of Spain and Portugal.

The Government intended that the command would in due course fall on Sir Arthur Wellesley, but Wellesley was a lieutenant general junior to Moore.

Not until Moore left the theatre of war could Wellesley take on the role of commander-in-chief.

To this end the Government appointed two more senior, although less experienced or competent generals to take overall command; General Sir Hew Dalrymple and General Sir Harry Burrard.

Dalrymple and Burrard were yet to reach Portugal.

The Royal Navy convoy carrying Wellesley’s troops arrived off Mondego Bay on 30th July 1808.

Wellesley disembarked his army between 1st and 8th August 1808.

During this time, more troops commanded by General Spencer arrived and Wellesley received information that a further 10,000 men were on their way, as were the two senior officers who would take over command from him.

After a period assembling land transport in the area, on 10th August 1808, Wellesley broke camp and began his march on Lisbon in the south of Portugal.

The French General Loison was inland with a division of troops.

Marshal Junot recalled Loison to Lisbon and sent General Delaborde with a force to hinder Wellesley’s advance and assist Loison in his withdrawal.

On 17th August 1808, Wellesley defeated Delaborde’s force at the Battle of Roliça and forced its hurried withdrawal towards Torres Vedras and Lisbon.

On 18th August 1808, Wellesley reached Vimeiro, where his army covered the landing in the mouth of the River Maceira of General Anstruther’s and General Acland’s brigades.

Marshal Junot prepared to advance and attack the British, first distributing garrisons around Lisbon. His field army assembled at Torres Vedras.

Wellesley also planned to advance and attack Junot.

On the evening of 20th August 1808, Wellesley learnt that the British frigate HMS Brazen was in the bay with General Sir Harry Burrard, Wellesley’s superior officer, on board.

Before Burrard could land from the frigate, Wellesley went aboard and gave Burrard a frank view of the situation.

Wellesley’s assessment was that the British outnumbered the approaching French army, although the French cavalry was significantly stronger than the single regiment of light dragoons, the 20th, in Wellesley’s army.

Supplies were difficult to procure ashore and the army was dependent on the fleet.

A shortage of horses left the artillery almost incapable of movement, while the French artillery was larger and fully mobile.

Burrard took the view that the army must await the arrival of Sir John Moore’s Corps from England before hostile operations could begin and ordered Wellesley to abandon his planned advance.

In the Lisbon area Marshal Junot was assembling his army to take the offensive against the British landing.

An appearance by a few British ships off Lisbon, a feint arranged by Wellesley, caused Junot to commit 7 battalions, comprising 6,000 men, to defensive positions around the city, significantly reducing the size of his field army.

On 15th August 1808, Junot marched north with 2 battalions of infantry, a cavalry regiment, a squadron of volunteers and 10 guns, with a substantial convoy of supplies.

Junot was joined by Loison and finally by Delaborde, after his defeat at the Battle of Roliça, giving Junot a force of 13,000 men and 23 guns, which he formed into 2 divisions of infantry, each of 2 brigades, a reserve of grenadiers, around 11,000 men and a cavalry division of 2,000 men (as set out in the ‘order of battle’ above).

This army constituted just over half Junot’s total force in Portugal.

Aware that he had committed too much of his force to defending the Portuguese capital, Junot sent orders for further troops to come up from the Lisbon garrison. These troops were unable to join him before the Battle of Vimeiro.

On 19th and 20th August 1808, Junot’s cavalry spread around the British camp, restricting movement by small bodies of troops. However, the disembarkation of the two newly arrived British brigades continued.

Junot had the French general’s supreme contempt for the armies of other nations and resolved to attack the day after his arrival, on 21st August 1808, in spite of the clear disparity in numbers between his own army and Wellesley’s.

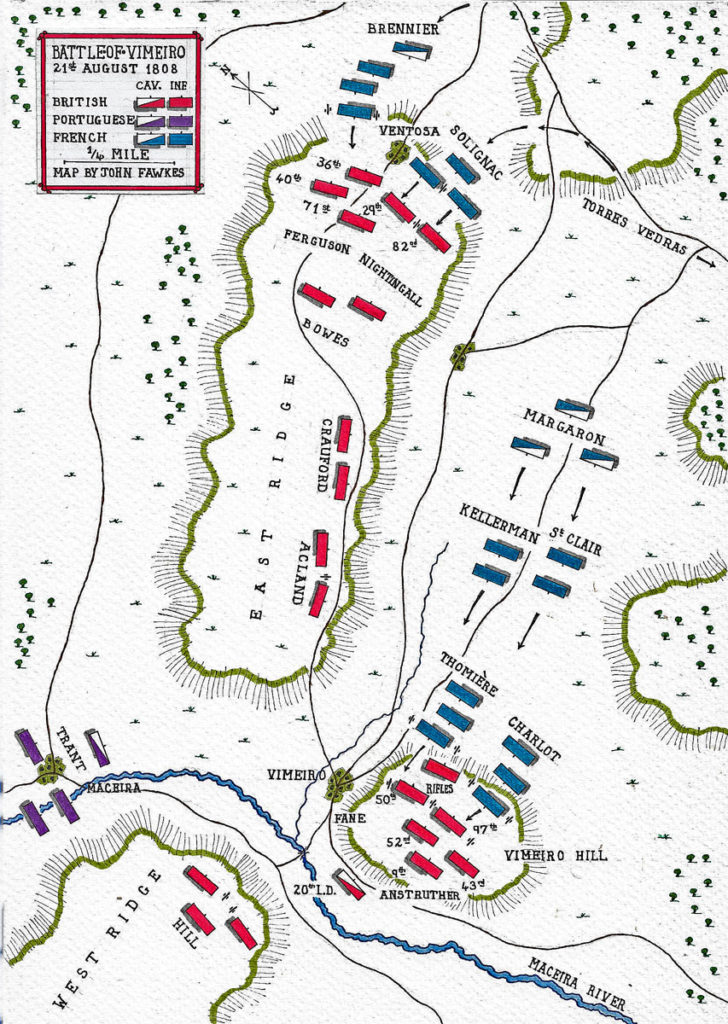

The position at Vimeiro:

The village of Vimeiro lies behind and to the north of a low hill. Behind Vimeiro, rises a high steep ridge that runs west to east from the coast before curving to the north-east.

At the point where the ridge turns north-east, behind Vimeiro, the ridge is split by a steep gorge, in which the Maceira Stream runs.

The part of the ridge to the west of the Maceira Stream is referred to as the West Ridge; the part of the ridge to the north-east of the Maceira Stream is referred to as the East Ridge.

The hill to the south of Vimeiro is referred to as Vimeiro Hill.

The village of Maceira lies at the northern end of the gorge.

The village of Ventosa lies at the north-eastern end of the East Ridge.

The lengths of each of the two ridges is approximately 1 ½ miles. The distance from Vimeiro village to Ventosa is approximately 1 ½ miles.

The Battle of Vimeiro:

Wellesley’s army was encamped in the area waiting to advance, not positioned for battle.

Most of the army was on the Western Ridge, where there was a good supply of water, essential for an encampment: Hill’s, Craufurd’s, Nightingall’s, Acland’s, Bowes’ and Ferguson’s Brigades with 8 guns.

Only the 40th Regiment was on the Eastern Ridge, where there was little water.

Trant’s Portuguese Brigade was at Maceira.

Fane’s and Anstruther’s Brigades were on Vimeiro Hill.

The 20th Light Dragoons, the rest of the artillery, 400 bullock carts and 500 pack mules were encamped on the flat ground to the north and west of Vimeiro.

Infantry picquets were in forward positions with the cavalry patrolling out towards Torres Vedras.

In the early hours of 21st August 1808, a German officer serving in the 20th Light Dragoons rode into Wellesley’s headquarters and reported that the French army was within an hour’s march of Vimeiro.

Wellesley ordered guns to be brought onto Vimeiro Hill; three 9 pounders and three 6 pounders.

The troops were under arms by dawn, as was the practice.

At around 7am, a dust cloud announced the imminent arrival of the French army, however not on the road from the south leading directly to Vimeiro, but on the parallel road, 6 miles to the east.

At 8am, Margaron’s cavalry advanced over the hills to the east of Vimeiro, while Junot’s infantry and guns came up behind them.

Junot, after surveying the scenery in front of him, decided to occupy the East Ridge, which appeared unoccupied, with a single brigade, while he attacked Vimeiro Hill from three sides with the rest of his infantry.

At about the same time, Wellesley was bringing Acland’s brigade up onto the West Ridge.

Junot directed Brennier’s Brigade, comprising the 4 battalions that had fought under Delaborde at Roliça, with a regiment of dragoons, to advance onto the East Ridge.

Brennier was to continue north and, turning west, to advance onto the East Ridge at its furthest point.

Junot’s intention was, as soon as Brennier’s attack was well under way, to launch an assault on Vimeiro Hill.

Seeing the dust arising from Brennier’s move to the north, Wellesley ordered Ferguson’s, Nightingall’s, Bowes’ and Acland’s Brigades to move to the East Ridge.

Craufurd’s Brigade marched to Maceira to support Trant.

Fortescue concludes that Junot probably saw the move of the brigades from the West Ridge, but that they would have gone out of sight behind Vimeiro Hill, leading Junot to conclude that the move was to reinforce the British in Vimeiro village.

The French attack on Vimeiro Hill was made by Thomière’s Brigade and Charlot’s Brigade, comprising 4 ½ battalions.

Delaborde led Thomière’s on the right and Loison led Charlot’s on the left, with 7 guns.

The French attack on Vimeiro Hill fell on Fane’s Brigade (1st/50th, 5th/60th and 4 Cos 2nd/95th Regiments) on the British left and Anstruther’s Brigade (2nd/9th, 2nd/43rd, 2nd/52nd and 2nd/97th Regiments) on the British right.

The British infantry were supported by 12 guns.

Due to the nature of the ground and the tree cover, the French approached unseen until they were 900 yards from the British line.

The French deployed to their left and advanced swiftly in dense columns, supported by the fire of their guns.

The British replied with the fire of their 12 guns and the rifle fire of Fane’s 60th and 95th Rifles, advancing in skirmishing order.

The French paused at a hedge running along the rim of the hill, before pushing on behind the retreating British skirmishers.

Thomière’s attack fell on the 50th Regiment, on the left flank of Fane’s Brigade.

The French column inclined to the right, leaving Colonel Walker, commanding the 50th, free to wheel his right wing round the flank of the French column.

Walker’s right-hand companies fired into the French column and the regiment charged.

The drivers of 3 French guns cut the traces of their horses, freeing them from the guns and galloped into their infantry, causing considerable disorder.

Further volleys from the 50th caused Thomière’s Brigade to break and rush back down the slope, in ‘utter rout and confusion’ (Fortescue’s words).

While Thomière was engaging Fane, Charlot advanced on Anstruther’s Brigade.

Anstruther’s regiments were largely concealed in the broken ground, the 97th in line with Fane, the 43rd behind the 97th’s right wing, the 52nd behind its left wing and the 9th behind the 52nd.

As Charlot’s Brigade emerged from a wood, 150 yards away, the 97th fired several volleys that shook the French column.

The 97th began to advance with increasing impetuosity.

Seeing that the 97th could not be restrained, Anstruther ordered the 52nd to double around the 97th ‘s left flank and attack the French column.

The combined charge of the 97th and the 52nd broke up the French column and drove it back down the hillside.

The attacking French force was completely disordered, all its guns captured and two of the French generals, Delaborde and Charlot, wounded.

Junot decided to commit his remaining infantry reserve, the four battalions of grenadiers, to an attack on Vimeiro Hill, under Generals St Clair and Kellerman, supported by 4 guns.

General St Clair led his two battalions of grenadiers along the road previously taken by Thomière.

As they advanced, the French grenadiers came under fire from British howitzers, brought forward from the reserve.

The howitzers were firing shrapnel shells and inflicted heavy casualties on the French troops with their bursting charges.

The French guns attempted to reply, but could only unlimber from time to time, to avoid being left behind by the hurrying infantry column.

St Clair’s grenadiers were about to deploy from their marching column when they came within range of three British battalions, waiting in line. The British troops unleashed a converging volley fire on the grenadier column.

The leading French platoons were annihilated and many of the artillery horses shot down, with both artillery colonels wounded.

The rest of St Clair’s column turned and fled down the hill into a gully.

General Kellerman was leading his two grenadier battalions.

along a hollow road quarter of a mile to the north, also heading towards Vimeiro.

Kellerman’s route took him around the left flank of Fane’s Brigade.

Anstruther sent the 43rd Regiment to hold the village of Vimeiro against Kellerman’s troops, while Acland, positioned on the East Ridge, opened fire with his guns and sent 4 companies of light infantry to fire into Kellerman’s flank.

The British 43rd met Kellerman’s grenadiers in the entrance to Vimeiro village and a confused and savage fight took place with bullet and bayonet, until Kellerman’s men were driven back.

Vimeiro Hill was covered with retreating French infantrymen and gunners, all the guns being abandoned to the British.

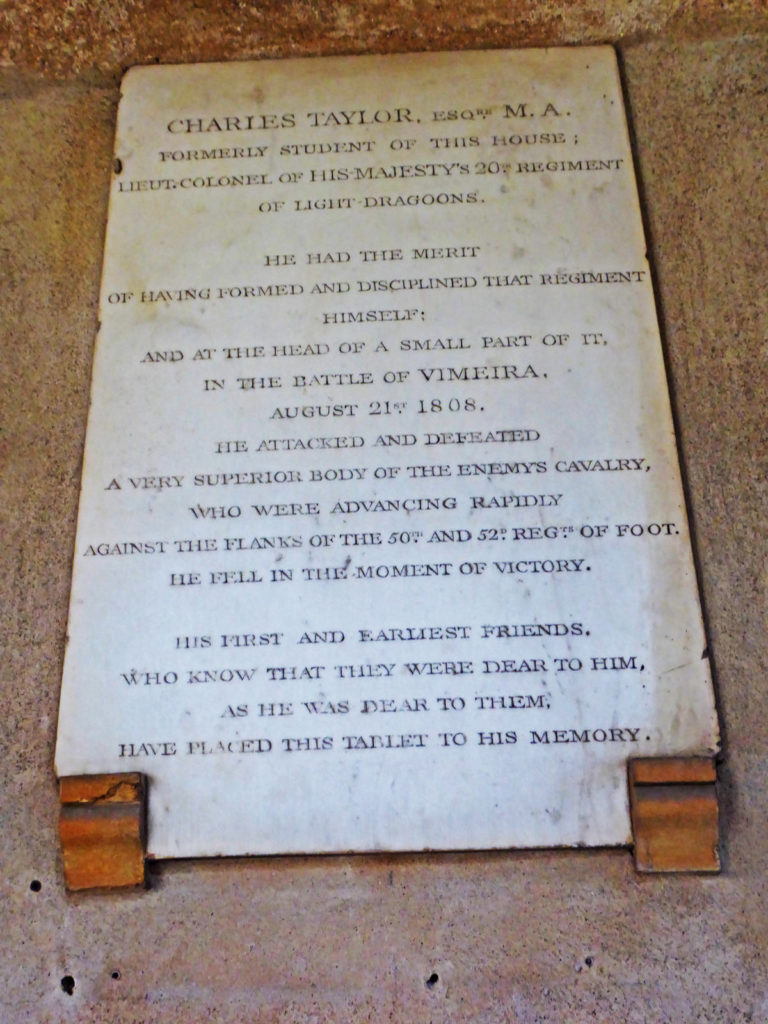

At this point, the British 20th Light Dragoons were led by their commander, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Taylor into the attack, cutting down the escaping French infantrymen.

General Margaron brought his cavalrymen forward and, charging the 20th Light Dragoons, dispersed them, killing Taylor and inflicting significant casualties on the regiment.

In the face of the threat from the French cavalry, the British infantry fell back to their positions on the hill.

It was only at 10.30am, when the fighting around Vimeiro was coming to an end, that the action on the East Ridge began.

During the attacks on Vimeiro Hill, Junot, becoming aware of the movement of the British brigades across the gorge onto the East Ridge and that Brennier was in danger of being heavily outnumbered, ordered Solignac’s Brigade with 6 guns to move to Brennier’s support.

Junot’s instruction to Brennier was to march his brigade north and, taking the track leading west, to come into the village of Ventosa and advance south-west along the East Ridge.

Brennier seems to have taken the next road to the north, which bypassed Ventosa and brought him, after a considerable delay, to the north-west side of the East Ridge.

Seeing the British troops moving across from the West Ridge onto the East Ridge and, fearing that Brennier would be heavily outnumbered, Junot sent Solignac’s Brigade of 3 battalions with 3 guns to support Brennier.

Solignac took the correct road and arrived at Ventosa, where he was confronted by the brigades of Ferguson, Bowes and Nightingall with 7 battalions.

The British troops were lying down behind the crest of the ridge and Solignac was unable to see the strength of the force he was confronting.

Solignac deployed his 3 battalions and led them to the attack up the steep slope, under a heavy fire from the British light infantry skirmishers.

At 100 yards range, the British infantry rose up and discharged two volleys before advancing with fixed bayonets.

Solignac was wounded and his brigade fell back in confusion, abandoning their guns.

Ferguson left the 71st and 82nd Regiments to guard the captured guns and pursued the retreating French troops with the 36th and 40th Regiments.

Brennier, by this time coming up on Solignac’s right, was drawn to the fighting by the sound of firing and surprised the 71st and 82nd Regiments, which were not expecting a French counter-attack, particularly up the slope from the north.

The British regiments were driven back and the French guns retaken.

At this point, the 29th Regiment came forward and took Brennier’s men in the flank, while the 71st rallied and counter-attacked, driving the French infantry back into the ravine, from which they had surprised the two British battalions.

During this struggle the 71st used the captured French guns against Brennier’s troops.

Brennier, wounded, captured and taken to Wellesley, made indiscrete enquiries about the progress of the French assault on Vimeiro, revealing to Wellesley that Junot must have committed all his reserves in the various attacks.

At every point the French had been heavily defeated and their guns captured.

While Wellesley’s army outnumbered Junot’s, the victory had been gained by 12 British battalions fighting against 13 French, with a heavy preponderance of French guns and cavalry.

The only French success was Margaron’s overwhelming of the British 20th Light Dragoons.

The French infantry fled east, leaving the road to Torres Vedras open. 14 of Junot’s 24 guns were in British hands. From Wellesley’s British brigades, those of Hill, Craufurd and Bowes had not fired a shot. The remaining brigades were flushed with success. The road to Lisbon was open.

At this point Sir Harry Burrard came up and took over command of the army from Wellesley.

Wellesley said to Burrard ‘Sir Harry, now is your time to advance. The enemy are completely beaten, and we shall be in Lisbon in three days. We have a large body of troops which have not yet been in action; let us move them from the right on the road to Torres Vedras and I will follow the French with the left.’

Burrard refused to adopt Wellesley’s urgent proposal, ordering the army to stay put.

Ferguson sent an urgent message saying that the remnants of Solignac’s Brigade were in a ravine and it only needed British troops to seal off the ravine for the French brigade to be forced to surrender. Burrard refused Ferguson permission to take this step.

General Thiébault took command of the survivors from Brennier’s and Solignac’s Brigades and led them east to join Junot.

Due to the British failure to follow up the success at Vimeiro, Junot was enabled to reform his battered army and lead it back to Lisbon.

Casualties at the Battle of Vimeiro:

720 British troops were killed

or wounded.

The British regiments with the largest numbers of casualties were the 43rd Regiment with 118 killed and wounded, the 71st with 112 killed and wounded and the 50th with 89 killed and wounded.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Taylor of the 20th Light Dragoons was killed. The 20th Light Dragoons suffered 44 casualties, Taylor being the only officer casualty.

French casualties were around 2,000 killed, wounded or captured (several hundreds were made prisoner). 14 French guns were taken.

The French generals Delaborde, Charlot, Brennier and Solignac were wounded, Brennier being captured.

Medal and Battle Honour for the Battle of Vimeiro:

The Military General Service Medal 1848 was issued to all those serving in the British Army present at specified battles during the period 1793 to 1840 who were still alive in 1847 and applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one or more of the clasps. There were 21 clasps available for service in the Peninsular War.

The Battle of Vimeiro (mistakenly embossed on the clasp as Vimiera) was one of the clasps.

The battle honour ‘Vimiera’ was awarded to the following regiments: 20th Light Dragoons, 2nd Queen’s, 5th, 6th, 9th, 20th, 29th, 32nd, 36th, 38th, 40th, 43rd Light Infantry, 45th, 50th, 52nd Light Infantry, 60th, 71st, 91st and 95th.

Army Gold Medal:

In 1810 a Gold Medal was issued to be awarded to officers of rank of major and above for meritorious service at certain battles in the Peninsular War, with clasps for additional battles. The ‘Large Gold Medal’ was awarded to generals, the ‘Small Gold Medal’ to majors and colonels, with the medal replaced by a cross where four clasps were earned. The Battle of Vimeiro was one of the battles.

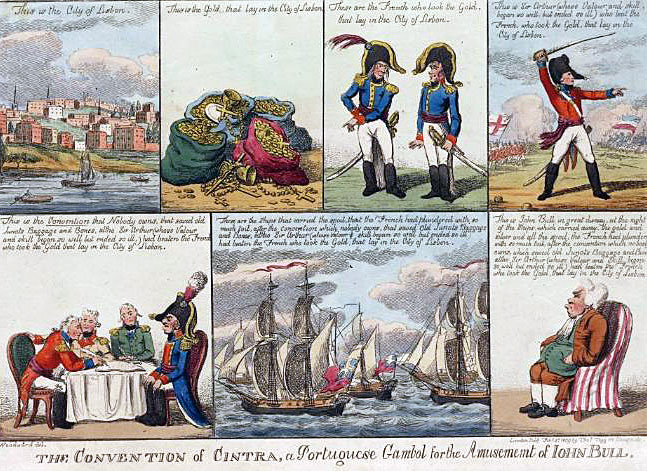

Follow-up to the Battle of Vimeiro:

After the Battle of Vimeiro, the French Marshal Junot asked for a capitulation on the terms that he and his army be repatriated to France on British ships.

The two British generals who had superceded Wellesley, Dalrymple and Burrard, agreed to the terms and the French Army was transported by the British Fleet to France, together with the loot the French had taken while in Portugal.

There was outrage in Britain and the three senior officers involved, Dalrymple, Burrard and Wellesley were subjected to an enquiry. Command of the British army in Spain passed to Sir John Moore.

Sir Arthur Wellesley was exonerated by the enquiry and re-instated in command in the Peninsular. In the meantime, Sir John Moore had conducted the retreat to Corunna and been killed.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Vimeiro:

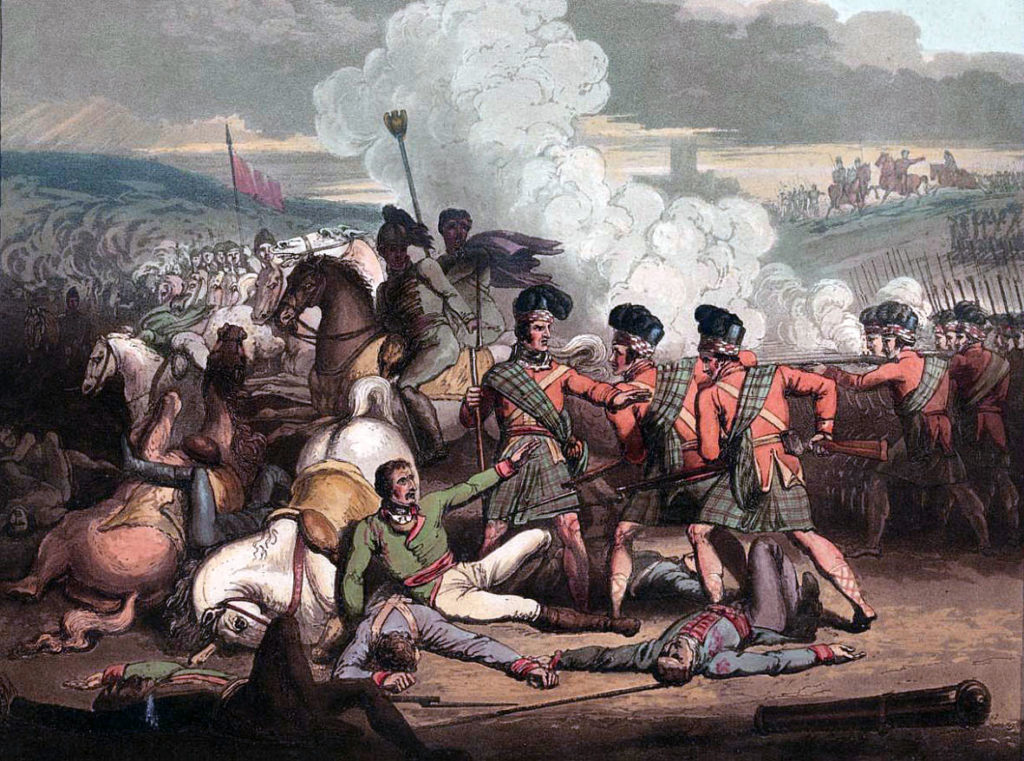

- It was a quirk of the Battle of Vimeiro that the French troops, due to the intense heat, wore their white linen fatigues and not blue field uniforms. The French in white coats are shown in many of the pictures of the battle.

- French cavalry: the designation ‘Provisional’ was given to a regiment assembled for a particular campaign with troops from a range of regiments.

- Fortescue describes the Battle of Vimeiro as ‘a great victory marred by the failure to follow up’. He places the blame for that failure squarely on Burrard who assumed command of the British and Portuguese army at the moment of victory through senior rank to Wellesley.

- British artillery used the ‘Shrapnel Shell’ for the first time at the Battle of Vimeiro. Developed by Lieutenant Shrapnel of the Royal Artillery, shrapnel shells exploded over the target, showering large numbers of bullets onto the enemy.

- During the fighting in Vimeiro, Sergeant Patrick of the 43rd Regiment and a French soldier were found dead, having bayoneted each other simultaneously through the body.

- Piper George Clarke of the 71st Highland Light Infantry was wounded during the Battle of Vimeiro, but continued playing his pipes, sitting on a rock. Piper Clarke was presented with a set of silver mounted pipes by the Highland Society of Edinburgh for his conduct at the Battle of Vimeiro.

- The friends of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Taylor, killed at the head of his regiment, the 20th Light Dragoons, at the Battle of Vimeiro, placed a memorial plaque in the cloisters of Christchurch College, Oxford, which states: CHARLES TAYLOR esq. M.A. formerly student of this House: Lieut: Colonel of his Majesty’s 20th Regiment of Light Dragoons. He had the merit of having formed and disciplined that regiment himself: and at the head of a small part of it, in the Battle of Vimeira, August 21st 1808. He attacked and defeated a very superior body of the enemy’s cavalry, who were advancing rapidly against the flanks of the 50th and 52nd Regiments of Foot. He fell in the moment of victory. His first and earliest friends, who know that they were dear to him, as he was dear to them, have placed this tablet to his memory.

- Following the Battle of Vimeiro, Wellesley’s senior officers presented him with a piece of plate, in appreciation for his leadership and victory over Junot. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the King of Prussia presented to the Duke of Wellington a set of plate portraying his victories over the French. A soup tureen showed the Battle of Vimeiro. This set is displayed in Apsley House.

References for the Battle of Vimeiro:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Roliça

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Sahagun

Podcast of The Battle of Vimeiro: Sir Arthur Wellesley’s victory over the French army of Marshal Junot in Portugal on 21st August 1808, his first major victory in the Peninsular War, which nearly ruined his military career: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcasts.