The British Light Division’s fierce battle to escape from Marshal Ney’s French corps across the River Coa on 24th July 1810 in the Peninsular War

British Light Division defending the bridge at the Battle of the River Coa on 24th July 1810 in the Peninsular War: picture by Christa Hook

13. Podcast of the Battle of the River Coa, the British Light Division’s fierce battle to escape from Marshal Ney’s French corps across the River Coa on 24th July 1810 in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Talavera

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Busaco

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of the River Coa: 24th July 1810

Place of the Battle of the River Coa: in eastern central Portugal near the Spanish border.

Combatants at the Battle of the River Coa: The British and Portuguese Light Division against the French.

Commanders at the Battle of the River Coa: Brigadier General Robert Craufurd commanded the Light Division against Marshal Ney.

Size of the armies at the Battle of the River Coa:

The British and Portuguese Light Division comprised the 14th and 16th Light Dragoons, 1st Hussars, King’s German Legion, 1st/43rd Light Infantry, 1st/52nd Light Infantry, 1st/95th Rifles, 1st and 3rd Portuguese Caçadores and Ross’s Troop of the Royal Horse Artillery, some 5,000 men.

Marshal Ney’s corps comprised some 30,000 men.

Winner of the Battle of the River Coa:

Craufurd’s Light Division crossed the River Coa in the face of a fierce attack by Marshal Ney’s Corps, in the process inflicting a reverse on the pursuing French troops.

Grenadier and Voltigeur of French Infantry: Battle of the River Coa on 24th July 1810 in the Peninsular War: picture by Bellangé

Background to the Battle of the River Coa:

In the spring of 1810, the French Emperor Napoleon appointed Marshal Massena to command the second French invasion of Portugal.

Massena arrived at Salamanca in Western Spain on 15th May 1810.

Relations between Massena and the other senior French officers in Spain were not good.

Fortescue reports that ‘Ney and he (Massena) were old enemies; Junot was furiously jealous at being superceded in command of the Army of Portugal; Reynier, with or without reason he (Massena) disliked.’

At their first meeting, Massena said to his staff; ‘Gentlemen, I am here against my own wish; I begin to find myself too old and weary for active service’. Massena had been almost constantly on the battlefield for 18 years, suffering a severe fall from his horse at the Battle of Wagram in 1809.

It was a constant burden for the French commanders in Spain that Napoleon attempted to control their operations from Paris, with weeks elapsing between the issuing of orders and their arrival in Spain.

Napoleon gave his orders to the French commanders in Spain for the French invasion of Portugal before Massena arrived.

Massena was to advance on Ciudad Rodrigo with the Sixth and Eighth Corps, capture the city and move on to the Portuguese border fortress town of Almeida.

Reynier’s Fifth Corps was to operate in the area of Alcantara in the south of Spain, threatening Lisbon from the east.

Napoleon repeatedly declared that the invasion of Portugal should be conducted methodically and without haste, beginning in September 1810, when the heat of the summer was passed and the crops were in.

Little account seems to have been given to the opportunity this gave Wellington to prepare his defence, perhaps because Napoleon discounted the ability of the British to mount an effective resistance.

There were few routes from the Spanish border to Lisbon and, relying on earlier Portuguese plans for dealing with invasion from Spain, Wellington oversaw the stripping of sources of supply on the routes most likely to be taken by the invading French army.

On the isthmus leading to Lisbon, British and Portuguese army engineers prepared the strip of fortified points known as the ‘Lines of Torres Vedras’.

Wellington’s preparations involved the concentration of his main army in the area to the west of Almeida, in anticipation of Massena’s advance into Portugal at this point.

On 30th May 1810, Ney arrived outside Ciudad Rodrigo, with his Sixth Corps and a division of cavalry, while Junot’s corps came up in support.

The French began the siege of Ciudad Rodrigo on 15th June 1810, their lack of urgency causing Wellington considerable surprise

‘This is not the way in which they have conquered Europe’ was Wellington’s comment.

In a sharp action on 4th July 1810 between a division of French cavalry and Craufurd’s Light Division, the British were forced back over the Rivers Dos Casas and Turones.

On 10th July 1810, after a spirited defence, the Spanish garrison of Ciudad Rodrigo surrendered the city to the French.

Following the fall of Ciudad Rodrigo, Wellington warned Craufurd that he should pull his division across the River Coa, to the west bank, if threatened by a French advance.

Wellington repeated this requirement to Craufurd in several communications.

Fortescue devotes considerable space in his ‘History of the British Army’ to his analysis of General Robert Craufurd’s character and abilities.

Fortescue describes Craufurd as an unrivalled commander in outpost warfare and a superb trainer of troops, but out of his depth in straight battle. He describes Craufurd as a supremely ambitious, self-centred and undisciplined commander with little sense of judgement.

That the Battle of the River Coa took place at all was due to Craufurd’s refusal to obey Wellington’s repeated orders not to be caught on the eastern side of the River Coa and it was due to the skill and initiative of the subordinate commanders in the Light Division that the battle was not a disastrous defeat, Craufurd’s conduct in the battle making the crisis worse for the British, rather than better.

Battle of the River Coa:

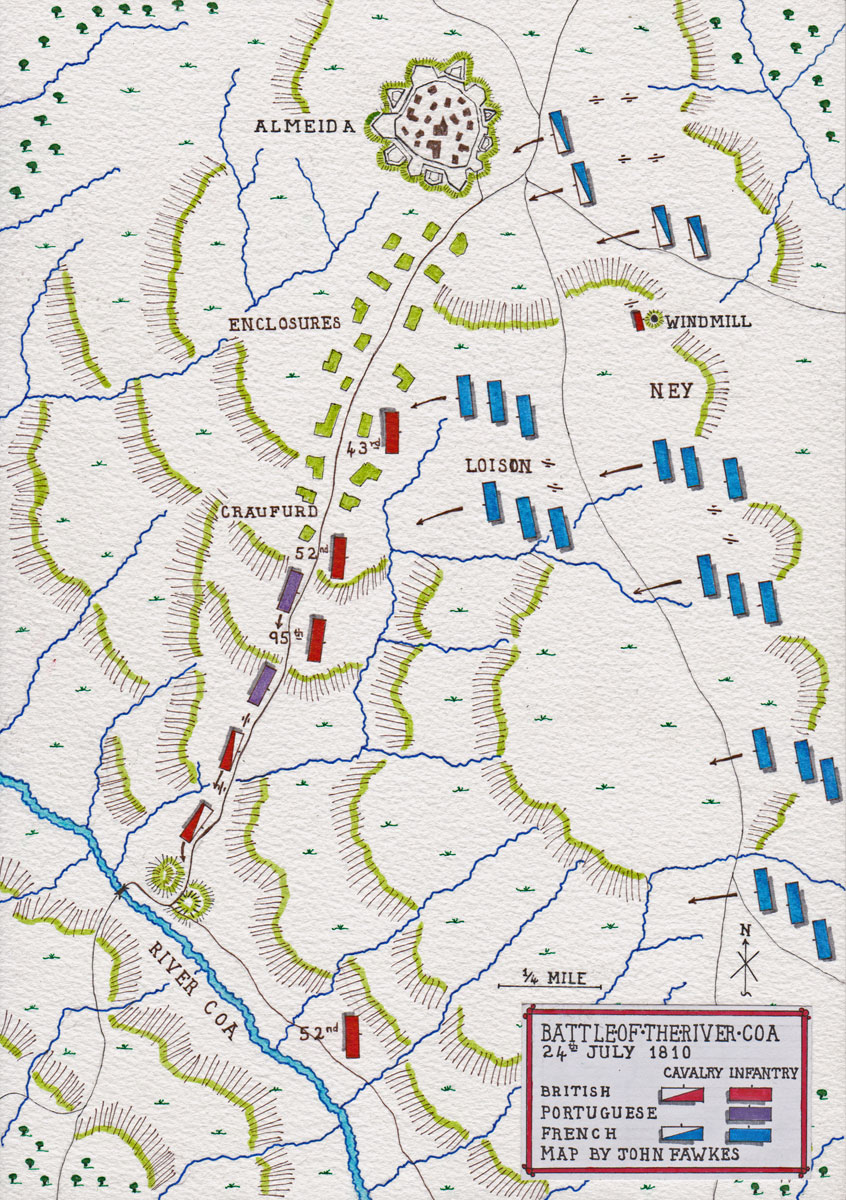

On 21st July 1810, Massena ordered Ney’s corps forward against Craufurd’s positions, which lay in a line to the south-east of the fortress town of Almeida, with the River Coa on the right flank, blocking Craufurd’s retreat to the south.

Ney halted three miles short of Craufurd’s positions along the ridge.

The fortress of Almeida lies on a plateau.

From Almeida a narrow steep road runs in a southerly direction down to the River Coa, which was crossed by a bridge that provided the only escape for Craufurd’s Light Division.

The upper stretches of the road were lined by walled allottments and orchards.

In the final approach to the bridge, the ground bordering the road was covered by rocks, making it particularly difficult for wheeled traffic to negotiate the approach to the bridge.

Fortescue describes the River Coa as a ‘boiling torrent’, due to the heavy rainfall.

Instead of complying with Wellington’s repeated orders and withdrawing his division, or at the very least the cavalry and guns across the River Coa, Craufurd maintained his position east of the river, with all his regiments, including his regiments of light cavalry and Ross’s battery of horse artillery.

Ney waited for several days before advancing to take advantage of Craufurd’s rashness with his full corps of around 30,000 men.

As Craufurd must have expected, the French attack, when it came, was fast moving and gave him little time to react.

Picquet of the 52nd Light Infantry holding the ruined mill at the Battle of the River Coa on 24th July 1810 in the Peninsular War

The left of Craufurd’s line lay around a ruined windmill, a half-mile to the south of Almeida, held by a half-company of the 52nd Light Infantry and two guns from Ross’s battery of horse artillery.

Next in line, to the south-west, lay the 43rd Light Infantry, the 95th Rifles, 1st Portuguese Caçadores, 3rd Caçadores and the 52nd Light Infantry.

The British cavalry formed picquets along the front of the line.

Craufurd’s line covered a mile and a half with its right on the River Coa.

Ney began his advance on the 24th July 1810, a wet and stormy day, but his corps took several hours to get under way.

Once the French troops began their advance they moved with speed.

British 43rd Light Infantry: Battle of the River Coa on 24th July 1810 in the Peninsular War: picture by Charles Stadden

The British cavalry and horse artillery were quickly forced back by the overwhelming strength of the French cavalry advancing against Craufurd’s left flank.

Craufurd’s near fatal error in failing to move his cavalry and guns through the awkward approach to the bridge and across the River Coa well in advance of the French attack quickly became apparent.

Even then Craufurd failed to order them to cross the river, forming them behind his left flank.

The French infantry advanced in force driving Craufurd’s line back to the road.

The regiments of Loison’s Division struck the left of Craufurd’s line, finding the Light Division’s regiments fragmented and dispersed among the enclosures lining the road, a series of traps from which the British infantry escaped with some difficulty.

In desperation, Craufurd ordered his three British battalions to hold their positions while the other regiments marched down the road to the bridge.

While the cavalry, guns and Portuguese infantry marched behind them, the 43rd, 52nd and 95th fought a savage skirmishing battle among the enclosures against 4 or 5 times their number of French troops.

French guns unlimbered at the top of the hill and opened fire on the retreating British force.

At the bottom of the hill, an ammunition limber overturned in the approach to the bridge, increasing the confusion as the French infantry closed in.

Several of the Light Division’s regimental officers showed the quality of their leadership in the absence of guidance from Craufurd.

Colonel John Charles Beckwith, 95th Rifles: Battle of the River Coa on 24th July 1810 in the Peninsular War

Major McLeod held one of the knolls overlooking the approach to the bridge with four companies of the 43rd Light Infantry, while Major Rowan held the knoll on the opposite side of the road with two companies of the 95th Rifles.

Under the protection of these two positions, he majority of the Light Division was enabled to cross the bridge, while the attacking French infantry was held at bay.

Once the division appeared to be crossing the bridge, Craufurd prematurely ordered Rowan’s 95th companies to leave the knoll they held and cross the river.

Craufurd overlooked the half battalion of the 52nd Light Infantry, still holding the right flank of the original line on the river bank, a mile and a half upstream of the bridge, with no instructions to withdraw.

Colonel Beckwith sent Major Charles Napier to find the 52nd and bring them to the bridge.

In the meantime, the French attacked McLeod’s party of the 43rd and drove them off the first knoll.

The bridge was still packed with Light Division troops crossing to safety.

McLeod led a determined counter-attack with the 43rd and 95th Rifles, recapturing the knoll and driving the French from behind a wall on the far side of the crest with such ferocity that the French were deterred from resuming their attack.

The 52nd appeared from their position further up the river and the remaining men of the Light Division were enabled to cross the bridge, even bringing the over-turned ammunition waggon.

Major Charles Napier assembled troops as they crossed the river and positioned them to defend the bridge against the inevitable French attack.

British 43rd Light Infantry crossing the bridge at the Battle of the River Coa on 24th July 1810 in the Peninsular War

On the west side of the River Coa, Craufurd dispatched his cavalry along the river to guard possible fording points, while Ross’s battery was positioned on the hillside and the 95th Rifles occupied the buildings overlooking the bridge.

Officer 52nd Light Infantry: Battle of the River Coa on 24th July 1810 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Very quickly the French skirmishers gathered along the river bank and engaged Napier’s men, while the French guns opened fire on the guns of Ross’s troop.

Soon on the scene, Ney ordered a search for a ford to enable his troops to outflank the British holding the bridge.

No such ford could be found and Ney ordered the grenadiers of the 66th of the Line to storm the bridge.

The French column was marching onto the bridge when the British light infantry and riflemen with Ross’s guns opened fire on them.

In a storm of fire, the officers and leading infantry files of the French grenadiers were mown down, the column being driven back with heavy loss.

Ney ordered a further attack by 300 picked marksmen, which came to grief in the same way, although a dozen men found cover on the British side of the bridge.

A third attack, carried out with significantly less enthusiasm than the first two, made no progress.

The combat continued with a steady artillery bombardment, until at around 4pm torrential rain brought firing to an end and the French fell back.

Casualties in the Battle of the River Coa:

French casualties in the Battle of the River Coa were 520 killed and wounded, most lost in the attack on the bridge at the end of the battle.

British and Portuguese casualties were:

1st/43rd Light Infantry: 11 officers killed or wounded, 116 soldiers killed, wounded or missing.

1st/52nd Light Infantry: 2 officers wounded, 20 soldiers killed, wounded or missing.

95th Rifles: 10 officers killed, wounded or missing and 119 soldiers killed, wounded or missing.

Portuguese (3rd and 5th Caçadores): 1 officer wounded and 30 soldiers killed, wounded or missing.

Cavalry: 1 officer wounded and 6 soldiers killed, wounded or missing.

Total British and Portuguese casualties 333.

Aftermath to the Battle of the River Coa:

While heavily criticising Craufurd for his errors in the battle, both in allowing it to take place by his insistence on remaining on the east bank of the River Coa in the face of overwhelming French forces and then by his mishandling of the battle, Fortescue points out that criticism must also fall on General Picton, whose division was specifically tasked with supporting the Light Division and when asked by Craufurd for support refused it in a bad tempered exchange between the two generals.

Battle Honours and Medal for the Battle of the River Coa:

The Battle of the River Coa is not a British regimental battle honour and there is no clasp for the Battle of the River Coa on the Military General Service Medal 1848.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of the River Coa:

- The half-company of the 52nd at the ruined mill on the British left flank was cut off by the swift French advance. Lieutenant Dawson, in command, kept his men hidden until nightfall before marching unobserved to Pinhel, where they rejoined the Light Division.

References for the Battle of the River Coa:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Talavera

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Busaco

13. Podcast of the Battle of the River Coa, the British Light Division’s fierce battle to escape from Marshal Ney’s French corps across the River Coa on 24th July 1810 in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s Britishbattles.com podcast.