The series of battles fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War; Wellington decisively repelling Marshal Soult’s incursion across the border to relieve the French garrisons in Pamplona and San Sebastian

Wellington at the Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: picture by John Singleton Copley

42. Podcast on the Battle of the Pyrenees: the battles fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War; Wellington decisively repelling Marshal Soult’s incursion across the border to relieve the French garrisons in Pamplona and San Sebastian: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

42. Podcast on the Battle of the Pyrenees: the battles fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War; Wellington decisively repelling Marshal Soult’s incursion across the border to relieve the French garrisons in Pamplona and San Sebastian: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Storming of San Sebastian

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of San Marcial

Marshal Soult: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

War: Peninsular War

Dates of the Battle of The Pyrenees: 25th July to 2nd August 1813

Place of the Battle of The Pyrenees: In the north-west section of the Pyrenees Mountains on the Spanish side.

Combatants at the Battle of The Pyrenees: British, Portuguese and Spanish against the French

Commanders at the Battle of The Pyrenees: General the Earl of Wellington against Marshal Soult.

Size of the armies at the Battle of The Pyrenees: 50,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish against 70,000 French troops.

Winner of the Battle of The Pyrenees: The British, Portuguese and Spanish.

Background to the Battle of The Pyrenees:

At the Battle of Vitoria on 21st June 1813, Wellington’s British, Portuguese and Spanish army defeated the troops commanded by Joseph Bonaparte and Marshal Jourdan, comprising the French Armies of the Centre (of Spain), the South (of Spain) and of Portugal. The French retreated towards the border between Spain and France in the Pyrenees Mountains followed by Wellington’s army, leaving garrisons in San Sebastian and Pamplona.

Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: picture by J.J. Jenkins

While the British Fifth Division, with Spanish and Portuguese troops, began the attack on the coastal city of San Sebastian and a Spanish force blockaded the French in Pamplona, Wellington positioned the rest of his army along the Pyrenees Mountain frontier between Spain and France.

The Emperor Napoleon, on hearing of the Battle of Vitoria, ordered Marshal Soult to return to Spain and take over command of the French armies in the country, in place of Joseph Bonaparte and his chief of staff, Marshal Jourdan. Soult was given the title of ‘Lieutenant of the French Armies in Spain and the South of France’.

Soult was ordered to save Pamplona and San Sebastian for the French interest, as an immediate aim and then to re-establish French control of Spain.

Spanish infantry: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: picture by the Suhls

Arriving at Bayonne, near the French-Spanish border, Soult set about re-organising the French army in the area and restoring its morale, before beginning his counter-attack against Wellington.

Soult formed the French armies from Spain into a Right Wing; commanded by Reille and comprising the divisions of Foy, Maucune and Lamartinière; a Centre; commanded by D’Erlon and comprising the divisions of Darmagnac, Abbé and Maransin; a Left Wing; commanded by Clausel and comprising the divisions of Conroux, Vandermaesen and Taupin; a Reserve under Villatte; a First Light Cavalry Division commanded by Pierre Soult (brother of the marshal) and a Second Dragoon Cavalry Division commanded by Treilhard.

Fortescue describes Marshal Soult in these terms: ‘…Soult was an extremely able administrator, acute of perception, keen of insight, swift and firm of decision. As a general his strategic gifts were remarkable. No man had greater skill in bringing his troops up to the battle-field, but in the actual combat he was weak, timid and diffident.’

British bivouac before the Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, in the Peninsular War

While Soult achieved a great deal in restoring the fighting spirit of the French army defeated at Vitoria and forced to retreat headlong into France, he faced considerable difficulties.

Napoleon was draining troops from the army in Spain to re-build his Grande Armée, leaving a shortage of officers and regiments understrength.

Used to quick campaigns in foreign countries, where they could subsist on the countryside, Soult’s troops were now on French soil and without a functioning supply system. The soldiers were compelled to loot their own countrymen.

In one incident a train of oxen assembled to move French artillery up to the border was set upon by starving French soldiers, who had to be driven away by force.

Nevertheless, Soult prepared to take the offensive against Wellington by advancing on his left across the Pyrenees Mountains towards Pamplona. Once that city was relieved the French would march to the north-west, thereby compelling Wellington to abandon his attack on San Sebastian.

Comte D’Erlon: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

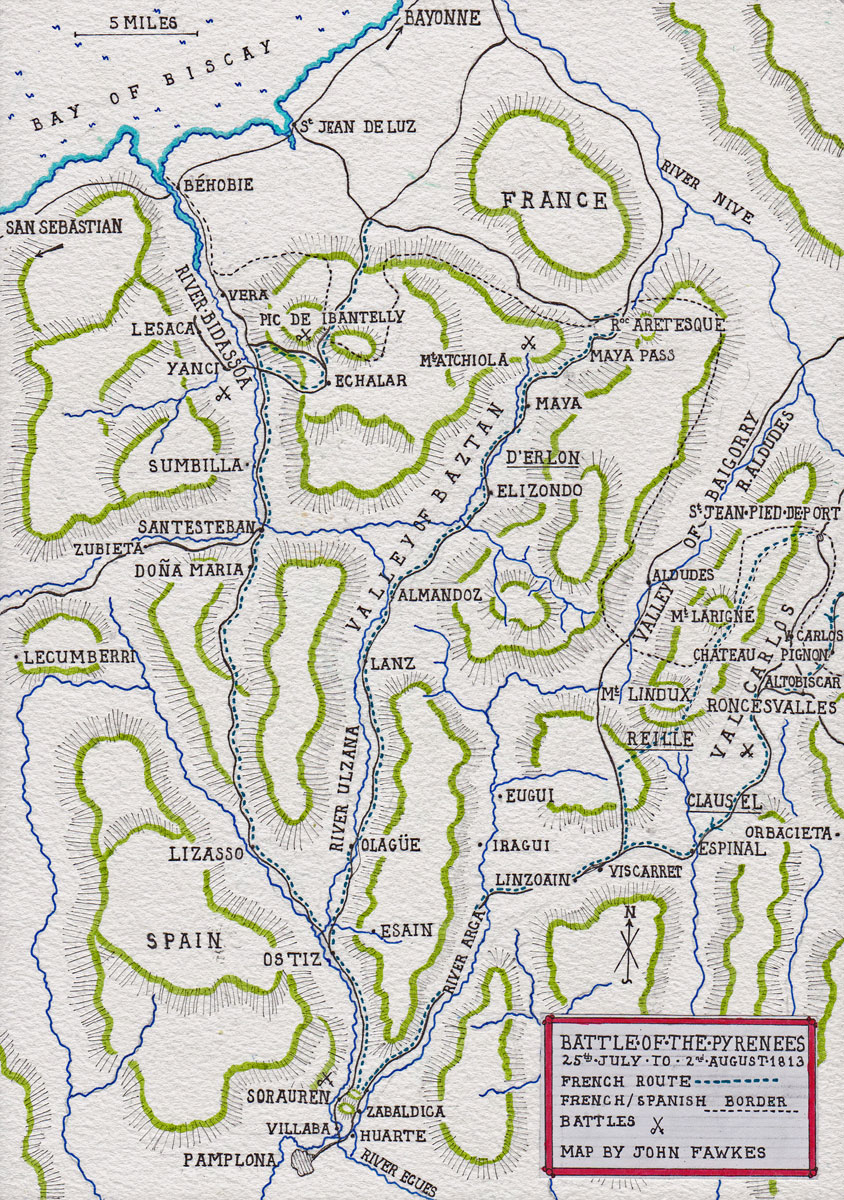

Fortescue describes the area in these terms: ‘the field of operations was the quadrilateral within the four fortresses of Bayonne on the north, St Jean Pied de Port on the east, Pamplona on the south, and San Sebastian to the west, all of which were in the possession of the French. …from Bayonne to St Jean Pied de Port is about twenty-seven miles…. From St Jean Pied de Port to Pamplona is about thirty miles; from Pamplona to San Sebastian forty miles; and from San Sebastian to Bayonne some twenty-nine miles….the principal lines of defence [in the coastal area between San Sebastian and Bayonne] are formed by three rivers……. the Nive… the Nivelle ….and the Bidassoa.

… In any advance upon Pamplona from the French side the great spine itself [the western arm of the Pyrenees Mountains] …. can be surmounted only by three principal routes. Of these the most westerly is the valley of Baztan….. these ingresses descend upon a single road ….. due south by …..Sorauren to Pamplona. The next valley to eastward is that of Baigorry, which follows the course of the river Aldudes, but has no issues southward except the roughest of tracks……… The third entrance is by the valley known as the Val Carlos ….. crossing the main ridge at the pass of Roncesvalles…..joining the road from the valley of Baztan at Villaba, runs with it into Pamplona.’

The roads in all of these valleys were bad…. and the lateral communications between them were even worse. Yet such lateral communications did exist…..But these rough tracks were practicable only for infantry and such cannon as could be carried on a mule’s back……’

Soult planned two simultaneous attacks, one on Maya down the Baztan Valley and the other, further east, down the Val Carlos by the Pass of Roncesvalles, the two advances to converge on Pamplona.

Map of the area between Pamplona, Sr Jean de Luz and St Jean pied de Port: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: the battle sites are marked by crossed swords. French routes are shown by dotted blue lines: map by John Fawkes

Positions of Wellington’s army:

The right wing of Wellington’s army was commanded by General Cole, commander of the Fourth Division.

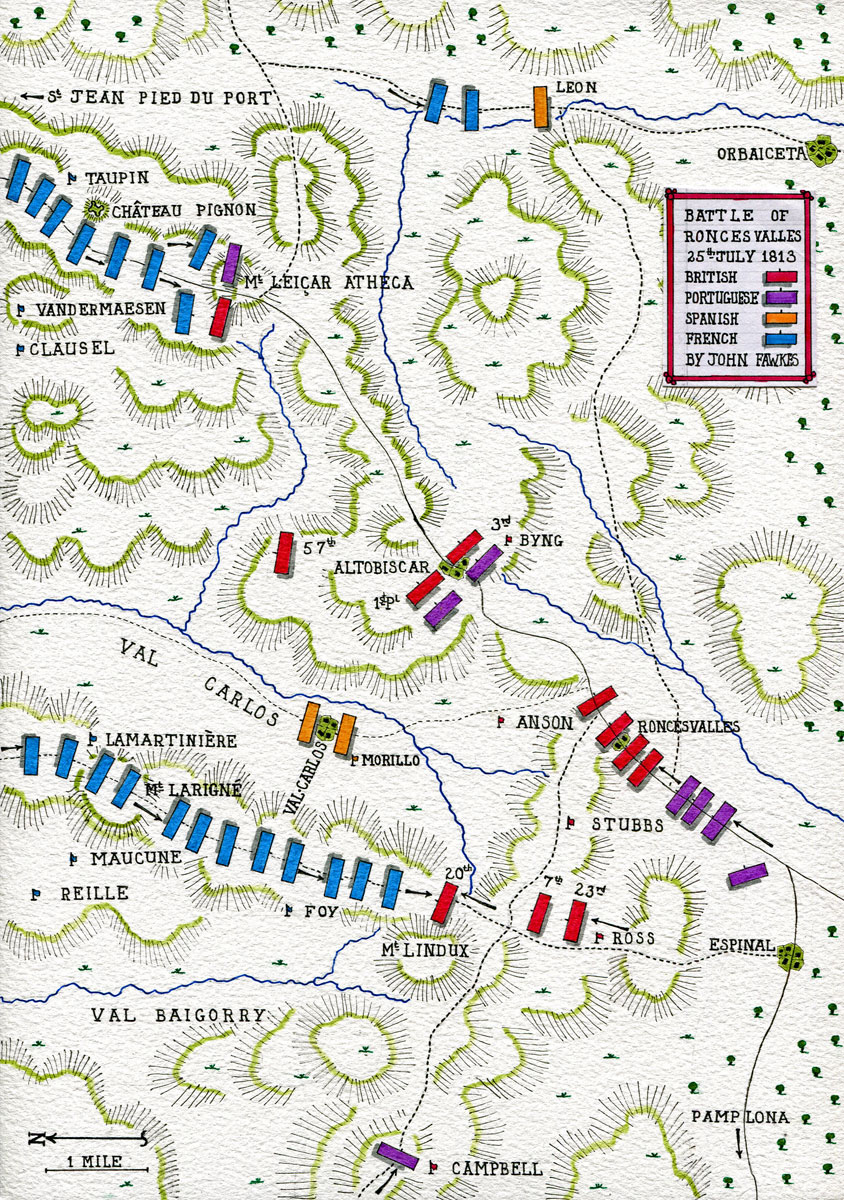

Byng’s British brigade of the Second Division, with two Spanish battalions, occupied Altobiscar, north-east of the Pass of Roncesvalles in the Val Carlos.

Morillo’s Spanish force stood to the south of the village of Val Carlos.

Campbell’s Portuguese brigade was at Aldudes above the valley of Baigorry.

The British Fourth Division lay at Viscarret, south-west of Roncesvalles.

General Hill commanded the centre, in the Baztan Valley, with the balance of the Second Division, a Portuguese brigade and some cavalry, amounting to 10,000 men.

Halting in the mountains during the Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, in the Peninsular War

Hill’s two British brigades of the Second Division, under General William Stewart, held the Pass of Maya in the Baztan Valley.

As a reserve for the Right and Centre, Picton’s Third Division lay at Olagüe.

The Light Division was at Vera to the north-west, the Seventh Division at Echalar and the Sixth Division at Santestaban.

Longa’s Spanish division on the extreme left formed a link with Graham’s Fifth Division at San Sebastian, the port city under siege.

Wellington’s headquarters lay at Lesaca.

The Battle of The Pyrenees:

Soult was informed on 15th July 1813 that the French garrison in San Sebastian could hold out for a further two weeks, enabling him to carry out his planned attack to relieve Pamplona, on Wellington’s right.

Sergeant 92nd Gordon Highlanders: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Soult ensured that on 22nd July 1813, Wellington received reports that the French were preparing to bridge the River Bidassoa at Béhobie, near the Atlantic coast. This caused Wellington to believe that Soult’s attack was to fall on his left, to relieve San Sebastian.

In fact, the bulk of Soult’s army was moving south-east along the mountain roads to St Jean Pied de Port, to attack Wellington’s centre and right.

Soult’s plan was for Reille’s three divisions of the Right Wing to advance down the crest that divided the valley of Baigorry from Val Carlos, to Mount Lindux and from there to dispatch forces to seize the key positions on each side of the crest.

At the same time, Clausel’s three divisions of the Left Wing, were to march down the road from Château Pignon to Altobiscar, via the Pass of Roncesvalles, to the east of the Baigorry Valley.

On the assumption that Byng, in the Pass of Roncesvalles, would feel compelled to retreat, Clausel was to continue his advance, join with Reille and continue a general advance on Pamplona.

The French attack was due to begin at 4am on 23rd July 1813.

Soult reckoned without the difficulty of moving large numbers of troops by bad mountain roads, in very wet weather.

St Jean Pied de Port, the starting point for the French advance, was overwhelmed by the number of largely starving French troops attempting to move through the town in the pouring rain.

Reille’s divisions were severely delayed in their advance.

Clausel’s divisions on the other hand were in position along the road leading south past Chateau Pignon by the night of 24th/25th July 1813.

Raids on British outposts warned Byng in the Pass of Roncesvalles that he could expect to be attacked the next day, information he passed to Cole, who ordered Ross’s Brigade to march to Lindux to cover Byng’s left flank. Anson’s Brigade and Stubbs’ Portuguese moved up to Espinal to replace Ross.

Battle of Roncesvalles on 25th July 1813: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

Battle of Roncesvalles:

At 6am on 25th July 1813, Clausel launched his attack on Byng’s Brigade with the 1st of the Line and the 25th Light from Vandermaesen’s Division. Soult, himself, supervised the attack.

Byng resisted strongly with his two battalions, 3rd Buffs and 31st/66th (the two battalions forming one provisional battalion, due to their small numbers).

At 10am, Clausel called off the attack, renewing it towards midday with more regiments from Vandermaesen’s Division.

Carabinier, Chasseur and Voltigeur of the French 25th Light; Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Byng continued to resist the overwhelming numbers until, at 3pm, his ammunition beginning to fail, he fell back to Altobiscar.

Cole arrived before Byng’s withdrawal and, seeing the advance of Reille on the west side of the Val Carlos, diverted Anson’s Brigade from its move to Orbacieta on Byng’s right, to support Stubbs’ Brigade at the head of the Val Carlos.

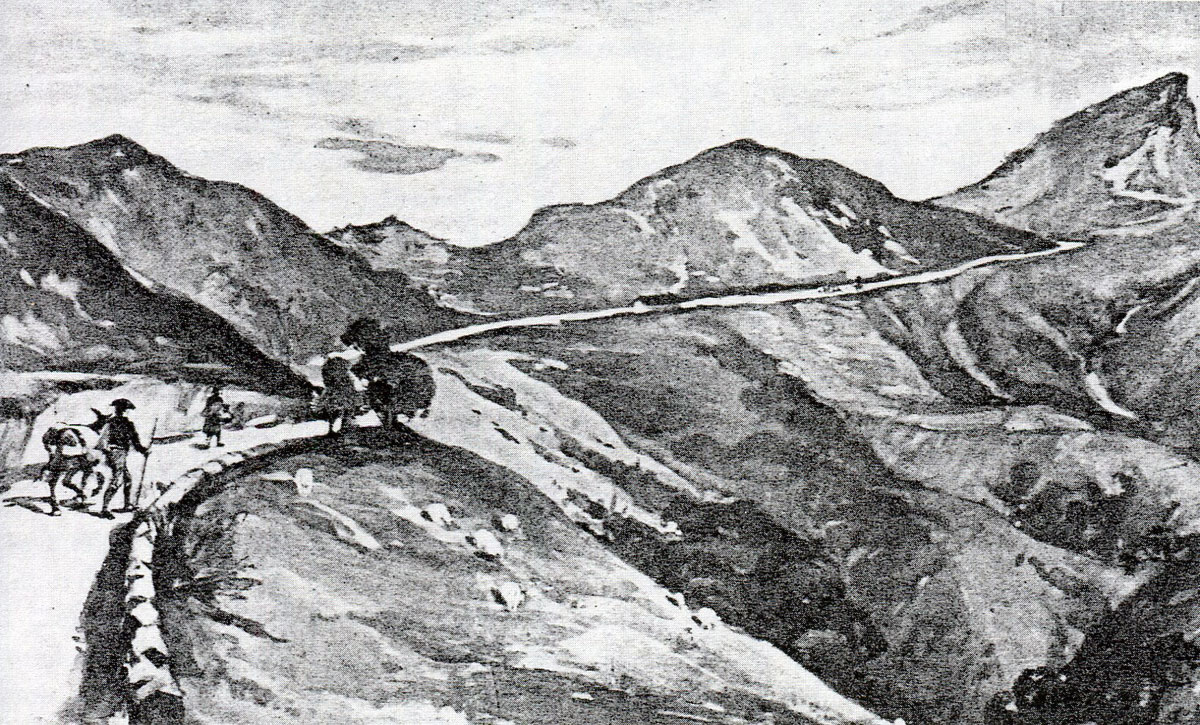

Pass of Roncesvalles: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

In mid-afternoon, a heavy fog came down on the mountains.

Byng, fearing that Clausel would send a force to Orbacieta that would outflank him on the right, fell back, having resisted an overwhelming French force for the majority of the day.

One of the French casualties was the wounded General Vandermaesen.

Clausel encamped on the night of 25th July 1813 at Altobiscar.

Reille’s advance on 25th to 31st July 1813:

Reille’s column set off at 6am on 25th July 1813, in parallel and to the west of Clausel’s advance.

Reille’s divisions were forced to march along a narrow path on the mountain ridge in single file. Consequently, Reille’s rear guard did not leave camp until around 1pm, when Reille’s advanced troops were still approaching Mount Larigné, two miles short of Lindux, the target for their attack.

The fight on Mount Larigné:

As the leading regiment of Foy’s Division, the 6th Light, was climbing Mount Larigné from the north, General Ross lead forward 3 companies of the 20th Regiment and a company of Brunswickers up Mount Larigné from the south.

A savage fight with the bayonet ensued, only resolved by the arrival of the full strength of the 6th Light which drove Ross’s men off the peak.

French troops in the mountains: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

In the meantime, the main body of Ross’s Brigade formed at Lindux and Foy’s advance was checked.

The bayonet fight cost Ross 181 men killed and wounded.

Ross’s Brigade of Cole’s Fourth Division comprised 1st/7th Royal Fusiliers, 20th Regiment, 1st/23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 3 Companies of Brunswick-Oels and 11th and 23rd Portuguese Regiments and 7th Portuguese Caçadores.

Reille’s advance was now considerably hampered by the nature of the ground. His troops were advancing along a ridge only 30 yards wide with steep slopes falling away on each side. The area was covered in thick scrub and was intersected by a deep trench dug in earlier fighting. Bringing up his divisions was a slow and difficult process.

The ground behind the British positions was much easier of access.

William Anson’s Brigade (3rd/27th, 40th and 48th Regiments) and Campbell’s Portuguese Brigade came up in Ross’s rear.

French National Guard: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Campbell, before coming up in support of Ross, had driven back a force of French National Guard and threatened Reille’s right flank, while counting Reille’s divisions as they passed, enabling him to give Cole an accurate assessment of the size of the French force that was advancing on Ross.

Reille’s leading division, Foy’s, finally got clear of the mountain path and Foy’s skirmishers began their attack on Ross’s men. They made no headway against the British.

The difficulty of negotiating the narrow hill-top path delayed the arrival of Maucune’s and Lamartinière’s Divisions until the evening.

The fog descended and all further attack was ruled out.

Reille’s force bivouacked where they stood at 7pm.

French casualties in the fight with Ross amounted to 370 killed and wounded.

At nightfall, General Cole decided to fall back, in view of the numbers he faced. Campbell’s report showed Cole that the French force facing him was at least three times the size of his own.

Soult’s plan was that Clausel and Reille be in command of the passes by the evening of 25th July 1813. Neither achieved this aim in full, but they had forced back Wellington’s forward units in the Baigorry Valley.

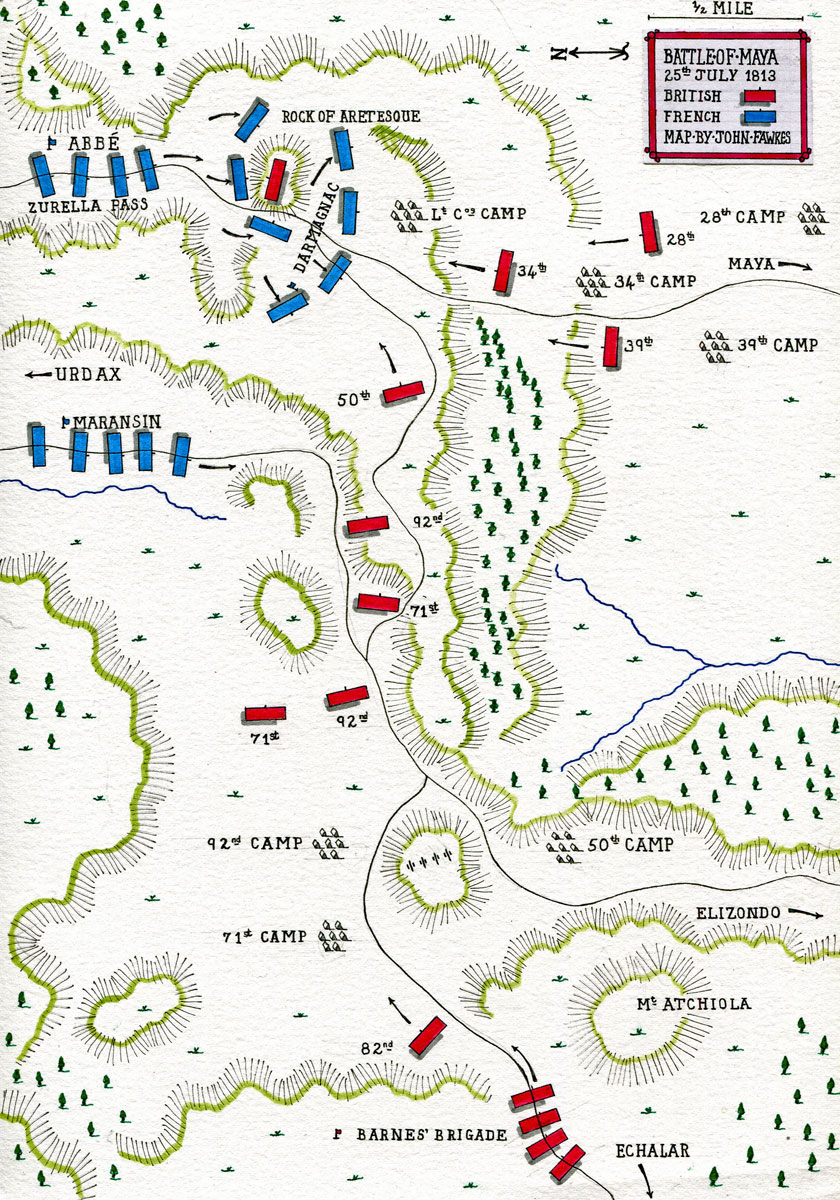

Map of the Battle of Maya on 25th July 1813: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

The Battle of Maya:

The British regiments holding the Pass of Maya, in the Bazantan Valley, to the west of the Val Carlos, were from Sir Roland Hill’s Second Division, temporarily led by General William Stewart, as Hill was in command of the whole right wing.

The brigades of the Second Division were; Cameron’s Brigade, comprising 1st/50th, 1st 71st Highland Light Infantry, 1st/92nd Highlanders and 1 company of 5th/60th Rifles and Pringle’s Brigade comprising 1st/28th, 2nd/34th, 1st/39th and 1 company of 5th/60th Rifles.

Pass at Maya, seen from the French side: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Stewart heard the firing from the neighbouring valley, where Campbell’s Portuguese were engaging the French National Guard.

Instead of staying with his command, Stewart rode down to Elizondo, to see what was happening.

Stewart took the view there was no threat from the French on his front. By leaving he left his troops with no overall direction.

French National Guard: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

The most advanced British post was the Rock of Aretesque, occupied by a piquet of 80 men from Pringle’s Brigade. The rest of the brigade, the 34th, 39th and 28th Regiments were encamped to the south of the Rock.

Cameron’s Brigade was encamped in the Maya Pass to the west of Pringle.

During the night of 24th July 1813, D’Erlon’s three divisions marched south towards the Maya Pass, assembling for the assault on the British positions by 9am.

The road down which the French were advancing, unobserved by the British, came south towards Pringle’s position before snaking to the west and then south again through Cameron’s position.

The initial French attack was to be made on the piquet at the Rock of Aretesque, whilst Darmagnac’s and Abbé’s Divisions advanced along the path circumventing the Rock of Aretesque.

Maransin’s Division was to halt on the main road until informed that the Rock of Aretesque was taken and then to attack down the Pass of Maya.

The piquet on the Rock of Aretesque was relieved at 7am on 25th July 1813. The incoming officer was Captain Moyle Sherer of the 34th Foot. The outgoing piquet commander informed Sherer that infantry and cavalry had been seen around dawn advancing down the pass.

Battle of Maya on 25th July 1813: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Sherer asked that this information be passed to General Stewart. The information was given to the Divisional Headquarters, but Stewart was by now absent, having ridden over to Elizondo.

A divisional staff officer came up to investigate the report and directed that the brigade’s light companies move up to the Rock of Aretesque.

Carabinier and Voltigeur of the 16th Light: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

The French attack on the Rock of Aretesque was made by Darmagnac’s Divisional voltigeurs and the 16th Light.

Sherer held back the French attack while the rest of the brigade assembled and hurried up the mountainside to his support.

The 34th Foot, in camp nearest the rock, came up and the regiment with the light companies resisted the French attack for several hours.

The French 8th of the Line skirted around the Rock of Aretesque and intercepted the other two battalions of Pringle’s Brigade, the 39th and the 28th, preventing them from reaching the summit and joining their comrades of the 34th.

Three more French regiments joined the attack on the Rock of Aretesque, forcing the 34th Foot to abandon the post and retreat to the main road. The 34th lost a substantial number of prisoners to the French, including Captain Moyle Sherer.

Maransin’s Division was now able to begin its advance into the Maya Valley.

All three of Clausel’s divisions met the regiments of Cameron’s Brigade coming up the valley.

The British 50th Regiment charged and drove back a force of French infantry emerging from the Zurella Pass, before forming up with the 34th Regiment.

These two regiments met the advancing troops of Darmagnac’s Division with destructive volleys, until forced back by the overwhelming strength of the French columns.

The 34th and 50th joined the right wings of the two Highland Regiments, the 71st Highland Light Infantry and the 92nd on the next ridge with 4 Portuguese guns.

Maransin’s Division emerged from the side valley and joined the French attack on Cameron’s Brigade and the 34th Regiment and the Portuguese guns.

Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

General Stewart arrived at this point and ordered the British regiments to fall back to Mount Atchiola, covered in turn by the left wings of the 71st and 92nd and the right wings of the 71st and the 50th.

150 men of the 92nd under Captain Campbell ran out of ammunition, while defending the crest of Mount Atchiola and were forced to roll stones down the hillside at the advancing French infantry.

At around 6pm, Stewart felt compelled to order a further retreat and the abandonment of Mount Atchiola.

Before this order could be given, General Barnes marched up with his brigade from Dalhousie’s Division (6th, 24th and 2nd/58th Regiments and the Brunswick Oels), answering an urgent call for assistance sent earlier by Stewart.

Soldiers of the 95th Rifles and 71st Highland Light Infantry and corporal of the 79th Cameron Highlanders: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Barnes led the 6th Foot and the Brunswick Regiment in an attack on Maransin’s advancing division, driving them back to the Maya Pass.

D’Erlon sent a brigade from Abbé’s Division to support Maransin, who was facing 3 battalions with 6 or more battalions. D’Erlon also recalled Damargnac from Maya to deal with the crisis brought about by Barnes’ attack.

The action soon came to an end, with D’Erlon’s advance brought to a halt.

Portuguese Cavalry Officer: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: picture by Denis Dighton

Casualties at the Battle of Maya:

Damargnac’s Division suffered losses of 1,400 killed and wounded.

Maransin’s Division suffered losses of 600 killed and wounded.

Abbé’s Division probably suffered losses of 500 killed and wounded.

The 92nd Highlanders suffered losses from a strength of 853 men of around 350 killed and wounded and 20 taken prisoner.

The 50th Foot suffered 44 men killed and 101 men wounded.

The 34th suffered losses from a strength of 530 men of 105 killed and wounded and 83 officers and men taken prisoner (including Captain Moyre Sherer).

The 39th suffered losses of 188 men killed and wounded and 22 missing.

The 28th Foot suffered losses of 157 killed and wounded.

The 71st Highland Light Infantry lost 7 officers and an unknown number of men at this particular part of the battle.

The 4 Portuguese guns were taken by the French.

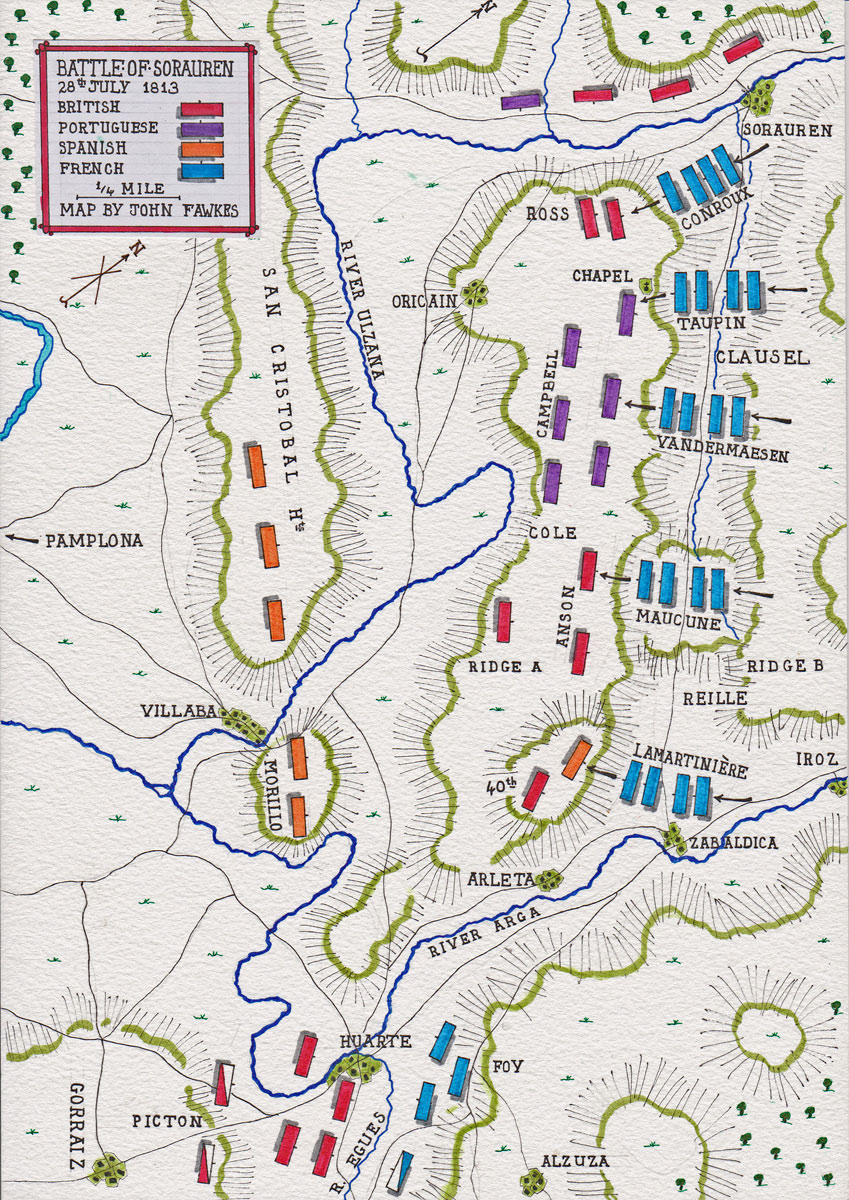

Battle of Sorauren on 28th July 1813: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

The Battle of Sorauren on 28th July 1813:

At nightfall on 25th July 1813, Cole withdrew to a position south of Linzoain, well on the road to Pamplona, abandoning the main ridge.

On 26th July 1813, Wellington received news of the fighting that had taken place in the Baigorry and Baztan Valleys, although without reliable detailed information as to what had happened. Communications in the mountains were difficult and information frequently incomplete.

Wellington made such dispositions as seemed appropriate, keeping his formations well forward in the centre and preparing to abandon the operation to take San Sebastian if necessary.

Highland soldiers: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: picture by Horace Vernet

Later in the day, Wellington rode to the Baztan Valley and obtained a reliable account of the Battle of Maya.

Late on 26th July 1813, Picton and Cole took the decision to fall back to Pamplona in view of the overwhelming French force they faced.

Early on 27th July 1813, Soult became aware that the British regiments the French had been battling in the eastern valleys were in full retreat.

Soult directed Reille to advance to the east bank of the River Ulzana, putting his corps behind Hill’s Division. Clausel was to march on Pamplona down the west bank of the Arga, with the artillery and cavalry.

D’Erlon’s Corps lay well behind the other two, due to D’Erlon’s failure to advance after the aggressive counter-attack by Barnes in the Maya Valley.

A sortie by the French garrison in Pamplona caused the Spanish force of O’Donnell to prepare to abandon the blockade of the city. O’Donnell was reinforced by the Corps of Carlos D’España, keeping him in place.

Picton’s Third Division and Cole’s Fourth Division were passing the town of Huarte, heading south-west, when Picton resolved to make a stand against Soult’s army.

At this point the valleys of the River Ulzana and the River Arga, converged to within two miles of each other, making it possible to block the French advances down each valley.

Picton directed Cole to take up a position between the two rivers.

Sorauren and Ridge A: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

The line Cole selected for his Fourth Division was a ridge running west to east, between the village of Sorauren on the River Ulzana and a conical hill above the village of Zabaldica, on the River Arga (Ridge A).

Ridge A was high, with a steep slope running into the valley along its north side, beyond which was a further ridge (Ridge B).

Picton’s Third Division, with the cavalry and artillery, adopted a position further to the south and east of Ridge A, along the River Egues, to the east of Huarte.

Morillo’s Spanish troops occupied a position between Huarte and Villaba, in direct support of Cole.

Two Spanish battalions, reinforced by a Portuguese battalion occupied the conical hill at the right-hand end of Cole’s position on Ridge A.

From right to left from the conical hill were posted; Anson’s Brigade, Campbell’s Portuguese Brigade and Ross’s Brigade, on whose flank was a chapel overlooking the village of Sorauren in the valley.

Byng’s Brigade stood in reserve behind Anson’s Brigade and Stubb’s Portuguese Brigade in reserve in the centre.

Clausel’s Corps marched down the valley of the River Arga and, on arriving at Zabaldica, Clausel sent a detachment up the conical hill to secure it, without realising that Ridge A was already occupied by Cole’s troops.

The Spanish battalions drove Clausel’s detachment back down the side of the conical hill.

Seeing that Ridge A was already occupied, Clausel marched his corps onto the ridge to the north of Cole’s ridge, Ridge B.

French Light Infantry Drummer: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

A further French attack was launched on the conical hill, but after initial success was again driven back.

During the course of the day Reille’s Corps made its way down the valley of the River Arga, encumbered with the baggage train, the artillery and the French cavalry.

D’Erlon still lay a long way north, in the Bazantan Valley.

Wellington made his way down the Ulzana River valley from Almandoz towards Sorauren.

Wellington issued orders for the British Sixth and Seventh Divisions to operate in the upper reaches of the Ulzana River, unaware that Soult’s army was already a considerable distance in advance of him and that they would be between Soult and D’Erlon’s Corps.

On reaching Ostiz, ten miles short of Sorauren, Wellington encountered Long’s Brigade (13th Light Dragoons) and was for the first time informed of Picton’s retreat to Huarte.

Leaving General Murray, his chief of staff, to prevent any troops from moving further south down the Ulzana River, Wellington galloped on down the valley, accompanied only by Lord Fitzroy Somerset, the one member of his staff sufficiently well mounted to keep up with him.

Wellington arrived at the bridge in Sorauren, to see the French divisions of Taupin and Vandermaesen along the ridge (Ridge B) facing Cole (on Ridge A).

Wellington despatched Somerset with orders for the Sixth and Seventh Divisions to leave the valley of the River Ulzana and march to Sorauren by a circuitous route to the west, with all speed.

Wellington then galloped his horse up the steep incline to join Cole at the summit, passing cheering Portuguese battalions of Campbell’s Brigade and British troops of Ross’s Brigade.

Wellington and Somerset at the Bridge in Sorauren on 27th July 1813: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: picture by Thomas Jones Barker

Arriving at the top of the ridge, Wellington rode onto a knoll, from where he could see the entire ridge and be seen by his own army and the enemy.

On the far side of the steep valley, the French divisions of Clausel’s Corps were taking up their positions (on Ridge B). In their midst could be seen Marshal Soult and his staff.

Soult’s plans were already unravelling. His intention was to attack with the entire strength of his four front-line corps, but Reille was struggling down the valley of the River Arga, instead of being in the valley of the River Ulzana, as his orders directed and D’Erlon was still far in the rear, advancing tentatively down the Ulzana.

The position taken up by Cole’s Fourth Division on Ridge A was a formidable one, due to the extreme steepness of the valley side, which was the only way the French divisions could reach the Spanish, British and Portuguese troops along the top.

Général de Division Damargnac: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

In the mid-afternoon, when Soult had still not delivered his attack, Wellington sent out orders to the divisions not present on the field; at dawn the Sixth Division was to march to Sorauren and the Seventh and Second Divisions were to follow.

If Soult deferred his attack further, he would face a significantly reinforced army.

Reports suggested that the French were planning to block the road to Sorauren, which caused Wellington to despatch 2,000 Spanish troops to keep the road open.

On the evening of 27th July 1813, Soult held a council of war with his generals and met near universal approval for a frontal attack on Cole’s position in the morning, only Clausel dissenting.

Soult’s orders were that Conroux’s Division was to move into the valley of the River Ulzana; Clausel’s three Divisions were to attack the western end of Cole’s position; Maucune and Lamartinière were to attack the eastern end of the ridge and the Spanish on the conical hill.

Foy, with the support of Pierre Soult’s Light Cavalry Division, was to move against Picton’s position at the eastern end of the line.

In the morning of 28th July 1813, Wellington sent the 40th Regiment to support the Spanish on the conical hill, but otherwise left Cole’s deployment unchanged.

Soult spent the morning reconnoitring the field, ordering that no move was to be made before 1pm.

Fortescue describes this delay as inexplicable, as Soult must have been aware that reinforcements were hurrying up, which would double the size of the force he was facing.

British 50th Regiment: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: print by Richard Simkin

At 10.30am, Pack’s Sixth Division began arriving from the west on the bank of the River Ulzana south of Sorauren.

Clausel sent Conroux’s Division into Sorauren, where heavy fighting broke out with Pack’s arriving troops.

Taupin’s and Vandermaesen’s Divisions were formed in the bottom of the valley and began their ascent to assault Cole’s men at the summit of Ridge A.

Clausel ordered Conroux to pull his men out of Sorauren and join the assault on the ridge.

Conroux’s men were brought to a halt by heavy fire from Campbell’s Brigade on the ridge and from the Sixth Division.

Taupin’s Division, by a supreme effort, reached the chapel and drove the 7th Caçadores back, but were then bundled off the ridge by a counter-attack from Ross’s Brigade and the 7th Caçadores.

Vandermaesen’s Division slowly scaled the steep hill-side, while Maucune’s men moved across the bridging ridge.

Battle of Sorauren: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

While this attack was initially successful against Ross’s Brigade and the 10th Portuguese, Wellington brought up Anson’s Brigade, which drove the French back down the hill-side into the valley.

On the left of the French attack, Gaulthier’s Brigade of Lamartinière’s Division attacked the conical hill. The French 120th and 122nd of the Line drove the Spanish back, but then encountered the British 40th Regiment, with which they exchanged volleys at close range, before being driven back down the hill.

On Soult’s extreme left, Foy’s men saw no action, other than a skirmish between hussars of each side conducted with firearms from the saddle, from which the French retired.

At 4.30pm, Soult called off the attack, having failed at every point to make headway against Cole’s men.

Wellington in the mountains during the Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Casualties of the Battle of Sorauren, first day:

Clausel suffered losses of 2,000 killed and wounded in his three divisions.

Maucune suffered losses of 600 killed and wounded in his division.

Gauthier suffered losses of ‘several hundred killed and wounded’

Fortescue states that French casualties can be taken at around 3,000.

The British, Portuguese and Spanish suffered losses of around 2,600 killed and wounded.

Battle of Sorauren, second day, 29th July 1813:

Having failed in his attack on the Sorauren Heights, Soult was bound to retreat. His troops were low on ammunition, without supplies and exhausted.

Soult abandoned his attempt to relieve the French garrison in Pamplona. Instead of advancing to the south-west, the French army would retreat north-west towards the coast and attempt to relieve the French garrison in San Sebastian.

Already the French reserves under Villatte were marching down the coast road in the direction of San Sebastian.

Grenadier and Voltigeur of a French Line Regiment: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: picture by Bellangé

On 29th July 1813, D’Erlon continued his march down the valley of the River Ulzana to Ostiz.

Soult’s instructed D’Erlon to leave the valley and march 5 miles north-west to Lizasso.

At Sorauren, Cole’s men were manhandling guns up onto the ridge, while working parties from both sides buried the dead from the previous day’s fighting.

In order to proceed with his march to San Sebastian, Soult had the difficult task of extricating Reille’s and Clausel’s Corps from the positions they had adopted for the previous day’s abortive assault.

Clausel was ordered to move into the valley of the River Ulzana, while Reille held the ridge facing Cole’s Fourth Division (Ridge B).

Once night fell Clausel was to march up the valley with Reille following.

Soult’s army would leave the Baztan and march through Lizasso for Santesteban.

At midnight, Foy’s Division left the heights of Alzuza and reached Zabaldica at 1am the next morning.

In the difficult process of moving his division along Ridge B, Maucune’s Division became delayed and was still on Ridge B when dawn came. British and Portuguese light troops moved forward and engaged the French columns.

The British and Portuguese artillery opened up on Conroux’s troops still in Sorauren and Maucune’s men on Ridge B.

After the uncertainty of command during the opening phase of the Battle of the Pyrenees, Wellington was now on the spot and firmly in control of his army.

Picton Third Division was marching up the River Arga from its position east of Huarte, ready to take Soult’s army in the rear by turning onto the ridge held by Reille (Ridge B).

Cole’s Fourth Division was ready to attack Reille in front, once Picton’s men were in action around the conical hill.

Byng’s Brigade, Pakenham’s Sixth Division and O’Donnell’s Spanish troops were advancing north, up the River Ulzana, ready to cut Reille off from the rest of Soult’s army.

Dalhousie’s Seventh Division was marching north, parallel with the River Ulzana, on the west bank and ready to take any opportunity to attack Soult’s men in the river valley.

Hill’s Second Division was further north, in the area of Olagüe, also looking for the opportunity to attack Soult.

Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Due to the delay on Ridge B, opposite Cole, Foy’s Division was forced to remain stationary under the artillery fire from the opposing ridge, while Picton’s Third Division advanced on his left flank and Pakenham’s Sixth Division threatened to cut off his line of retreat up the River Ulzana.

Wellington ordered a general attack along the line of Ridge B and on Sorauren.

Ordered by Reille to retreat out of Sorauren, Maucune’s men were forced to climb back up onto the ridge (Ridge B) instead of moving north up the river valley, while Byng’s Brigade stormed into the village from the chapel.

Maucune’s Division lost some 1,800 men in the fighting around Sorauren.

At the eastern end of Ridge B, Lamartinière’s Division fought desperately to hold back Picton’s advance in the area of Iroz, finally withdrawing further onto the ridge.

Cole’s men moved off the ridge and began an assault on Foy’s position.

The divisions of Reille’s Corps were collapsing into a disorderly mass on the ridge and escaping as best they could across the high ground to the north.

Taupin’s Division, leading the retreat by Clausel’s and Reille’s Corps in the Baztan Valley, took up positions in the hills to the east of Ostiz, facing south, in expectation that Reille’s corps would march up the river valley.

Battle of Sorauren during the Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, in the Peninsular War

Instead, the first formation to approach Taupin’s position was Dalhousie’s Seventh Division.

Taupin withdrew to Olagüe and finally joined D’Erlon at Lizasso.

The remains of Maucune’s and Lamartinière’s Divisions made their way up the River Ulzana valley, joining Clausel between Olagüe and Lizasso.

Foy took command of an assortment of units from his own division and other troops and directed them across the hills to the north, narrowly avoiding capture himself, reaching Esain at 1pm.

Foy’s column lost its way and found itself at Iragui in the valley of the River Arga, instead of the Ulzana River Valley, the Baztan.

Rather than risk the attempt to march west over the mountains to reach the Ulzana valley, fearing that he would be intercepted by Wellington’s troops, Foy marched north up the Valley of Baigorry to St Jean Pied de Port, implicitly acknowledging the failure of Soult’s operation to relieve either Pamplona or San Sebastian.

Other French troops finding themselves lost in the same area, made their way back to France via Maya.

Fortescue estimates that the operations so far had caused Soult losses the equivalent of two divisions.

During the morning of 29th July 1813, while Clausel and Reille were fighting the desperate battle around Ridge B, Soult, acting on information received from English deserters, decided that Hill’s Corps, further north in the Baztan Valley was isolated and vulnerable.

Soult hurried up the river to meet D’Erlon and ordered him to attack Hill’s position.

D’Erlon despatched Darmagnac’s Division to attack Hill in front, while Abbé outflanked Hill, occupying high ground on Hill’s left.

On receiving the French attack, Hill fell back to the next range of hills, where he was joined by Morillo’s Spanish and Campbell’s Portuguese.

With these additional forces, Hill kept this position for the rest of 30th July 1813.

Soult considered the battle was going well for him, without being aware of the disastrous outcome of the fighting around Sorauren.

Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Soult was disabused when Clausel and Reille arrived at his position in the area of Lizasso that evening and reported to him the devastating effect of the day’s fighting on their corps.

On the night of 30th July 1813, Soult’s army lay around Olagüe and Lizasso, no longer a fighting force, other than D’Erlon’s corps, having suffered around 15,000 casualties.

Wellington was, with difficulty, assessing what Soult’s plans were.

There were French troops making their way north up the valleys of Baigorry and Baztan.

Wellington laid his plans on the assumption that Soult proposed to retreat to France by the valley of the Baztan.

Wellington directed Picton’s Third Division to take the route through Roncesvalles, while Pakenham’s Sixth Division with Campbell’s Portuguese joined Picton by way of Eugui.

Cole’s Fourth Division was to march up the valley of the River Ulzana in the Baztan Valley, while Hill’s Second Division and O’Donnell’s Spanish were to move to Lanz in the Baztan Valley, to cut off the French retreat up the valley.

Dalhousie’s Seventh Division with Morillo’s Spanish were to march to the Pass of Doña Maria on the road to Santestaban.

Alten’s Light Division was ordered to march to Lecumberri, to cover any march by the French directly west and then return to Zubieta, 7 miles to the south-west of Santestaban.

The closing stages of the Battle of the Pyrenees:

For his retreat route, Soult chose the road via Santesteban, rather than the Baztan Valley.

D’Erlon’s men were too far to the west to get back to the Baztan Valley.

Soult assumed that Wellington would use the Baztan Valley for his advance, enabling the French to get away to the coast.

The route was to be via Santestaban, where Soult’s army would concentrate.

At 1am on 31st July 1813, Soult’s main body moved out along a road that was little more than a track.

51st Light Infantry: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

The French column of march was; Soult leading with two cavalry divisions and the artillery, followed by Reille’s two divisions, which marched up from Olagüe, with Clausel’s corps and D’Erlon’s corps in the rear.

Hill’s Second Division and Dalhousie’s Seventh Division caught up with the French rear-guard, formed of Abbé’s Division, in a wood north of Lizasso.

Stewart attacked Abbé’s Division in front while Dalhousie worked around his left flank.

Abbé extracted his men and fell back, but was attacked again.

Darmagnac’s Division took over as rear-guard, to be attacked in turn.

Finally, the onset of a heavy fog assisted the French to get away from their pursuers.

The tail of D’Erlon’s corps reached Santestaban late that night.

Wellington was unable to decide on the route Soult intended to take, due to the substantial difficulties of reconnaissance and communication in the mountainous region.

The confusion led to Wellington’s divisions being widely dispersed.

Initially Wellington was of the mistaken belief that the main French concentration was along the Ulzana River.

After the fighting around Lizasso, Wellington ordered Hill’s Second Division to move into the Baztan Valley.

Wellington himself went to Elizondo in the Baztan Valley, to find only a French convoy escorted by a single battalion, that was speedily dispersed by Byng’s Brigade.

Wellington received no communication from Picton in the Roncesvalles Valley or from Alten’s Light Division, whose brigades were adrift on the left, one even marching towards the south.

Finally, on the evening of 31st July 1813, Wellington was able to assess that six of Soult’s divisions were at Santestaban, with the remaining three in the valleys to the east, although much of Foy’s command, retreating up the Roncesvalles Valley, was little more than a mob.

Pyrenees Mountains by Delacroix: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Wellington now realised that much of his army was in the wrong place. In particular, Hill’s Second Division was in the Baztan Valley, leaving Dalhousie’s Seventh Division alone at Doña Maria, facing Soult.

Orders were immediately sent to Hill recalling him to Doña Maria and to Cole’s Fourth Division, ordering him to Santestaban, although he had a considerable distance to march from the Roncesvalles Valley.

Soult now realised that the Baztan Valley route back to France was no longer open to him and that he would have to take the road down the valley of the River Bidassoa to the coast or use difficult mountain tracks going north-east.

Reille was sent ahead to Sumbilla on the Bidassoa with Treilhard’s Dragoon Division and the artillery, with his infantry to follow.

On the morning of 1st August 1813, Reille despatched the 118th Regiment from Sumbilla to secure the bridge at Yanci, where the road to Echalar branches to the east from the Bidassoa valley road.

The rest of Soult’s army followed after Reille, with D’Erlon’s Corps in the rear.

Due to a number of mistakes in the route, Soult’s formations, weighed down by the many wounded being carried, became inter-confused and the retreat effectively came to a halt.

Cole’s Fourth Division caught up with the French rear-guard. His light companies deployed along the hilltops on each side of the road and fired on the French columns, causing casualties and further chaos.

Pyrenees Mountains by Delacroix: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

Action at Yanci:

General Graham, commanding the Fifth Division at San Sebastian, delegated to General Longa, commanding a Spanish Division, the task of intercepting Soult’s retreat down the River Bidassoa at Yanci, where a bridge crosses the Bidassoa.

Of Longa’s force, only two companies took up position at the bridge, but they were sufficient to bring the French retreat to a halt, by firing into the crowded road.

The Spanish companies were driven off, enabling the French to establish a flank guard and resume their retreat past Yanci.

In the evening, the first brigade of Alten’s Light Division arrived, after a forty mile march, drove the French flank guard off, took up positions along the road and opened fire on the French troops attempting to pass along the road.

By the time the whole brigade was in position, there were three battalions of the 95th Rifles spread along the road, firing into the French column.

The riflemen were concealed in the undergrowth and unreachable on the far side of the river, the French penned onto the road by the steep mountains and unable to escape from the British fire.

The French cavalry rode through the infantry to get through and escape, while French infantrymen looted their baggage and the wounded were abandoned.

Several French formations dispersed into the hills to escape the riflemen’s fire.

Finally Darmagnac’s division drove the Spanish off the bridge and managed to hold back the British riflemen until the remainder of the French troops passed.

The action ceased with the onset of darkness.

During the night Soult’s army lay around Echalar or on the road to Vera in ruins.

Many of the French regiments ceased to exist as disciplined bodies.

Maucune’s Division numbered less than a thousand men. The 1st Regiment of the Line from Vandermaesen’s Division numbered 27 men.

Fortescue states: ‘The French had lost nearly all their baggage and several hundreds of prisoners, and were left without food, without ammunition, without discipline, and without confidence.’

At the end of the 1st August 1813, Wellington’s troops were positioned with his headquarters at Santestaban, Alten’s Light Division at Yanci, Cole’s Fourth Division on the road between Yanci and Sumbilla, Dalhousie’s Seventh Division between Sumbilla and Santestaban and Hill’s Second Division near Maya.

Action at Echalar:

On 2nd August 1813, Soult moved north, the road down the Bidassoa Valley towards the coast being closed to him by the presence of Alten’s Light Division at Yanci.

Soult’s force took up a position across the road between Echelar and Sarre near the French border.

Clausel’s Corps occupied a position along high ground, with Reille’s Corps to its right rear and D’Erlon’s Corps to its left rear.

Wellington’s troops advanced to attack; Alten’s Light Division moving by way of Lesaca, across the main Vera road and into the mountains to the Santa Barbara heights; Cole’s Fourth Division and Dalhousie’s Seventh Division advancing through Echalar.

Attack of Barnes’ Brigade at the Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War

The first formation to make contact with the French was Barnes’ Brigade of the Seventh Division (6th, 24th, 2nd/58th Regiments and Brunswick Oels).

Without waiting for support, Barnes immediately attacked the divisions of Conroux and Vandermaesen, a force four times the size of his own.

The French troops, dispirited and low in ammunition, began to give way. Even when Vandermaesen’s Division joined the action, Barnes men were only held back for a short time, before the French line broke.

During this fighting, Kempt’s Brigade of the Light Division climbed the Pic de Ibantelly and attacked Reille’s Corps. Here also the French line dissolved.

During the afternoon, Soult’s army fell back from the crest of the mountain line that marked the border with Spain and withdrew back into France.

Both sides substantially resumed the positions they occupied before Soult’s incursion to relieve Pamplona two weeks before.

The Aftermath of the Battle of The Pyrenees:

The battle marked the near-end of Napoleon’s ambitions in Spain.

Marshal Soult would make one last attempt to renew the French conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

Casualties at the Battle of The Pyrenees:

French casualties (from Les Archives de la Guerre):

Reille’s Corps

Foy’s Division: Officers: 6 killed, 9 wounded, 0 captured: Men: 78 killed, 193 wounded and 69 captured: Total casualties 555

Maucune’s: Officers: 14 killed, 17 wounded, 25 captured: Men: 789 killed, 500 wounded and 1,102 captured: Total casualties 2,457

Lamartinière’s Division: Officers: 10 killed, 16 wounded, 3 captured: Men: 79 killed, 657 wounded and 216 captured: Total casualties 981

British soldier capturing 2 French officers: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: picture by John Augustus Atkinson

D’Erlon’s Corps

Darmagnac’s Division: Officers: 13 killed, 65 wounded, 1 captured: Men: 191 killed, 1,925 wounded and 30 captured: Total casualties 2,225

Abbé’s Division: Officers: 9 killed, 21 wounded, 1 captured: Men: 130 killed, 560 wounded and 29 captured: Total casualties 750

Maransin’s Division: Officers: 11 killed, 34 wounded, 0 captured: Men: 105 killed, 783 wounded and 126 captured: Total casualties 1,059

Clausel’s Corps

Conroux’s Division: Officers: 16 killed, 35 wounded, 12 captured: Men: 145 killed, 1,432 wounded and 747 captured: Total casualties 2,387

Vandermaesen’s Division: Officers: 16 killed, 30 wounded, 2 captured: Men: 153 killed, 978 wounded and 301 captured: Total casualties 1,480

Taupin’s Division: Officers: 6 killed, 38 wounded, 0 captured: Men: 125 killed, 1,007 wounded and 26 captured: Total casualties 1,202

1st Cavalry Division: Officers: 0 killed, 2 wounded, 1 captured: Men: 10 killed, 25 wounded and 16 captured: Total casualties 54

2nd Cavalry Division: Officers: 0 killed, 2 wounded, 1 captured: Men: 12 killed, 33 wounded and 19 captured: Total casualties 67

Total: Officers: 101 killed, 277 wounded, 45 captured: Men: 1,807 killed, 8,268 wounded and 2,665 captured:

Total French casualties 13,163

The casualties in Wellington’s army were around 4,000 killed, wounded and captured.

British regimental casualties:

Royal Artillery lost Officers 0 killed and 1 wounded: Men 1 killed and 19 wounded

14th Light Dragoons, no casualties

2nd lost Officers 0 killed and 1 wounded: Men 1 killed and 9 wounded

3rd lost Officers 1 killed and 1 wounded: Men 3 killed and 27 wounded

6th lost Officers 1 killed and 7 wounded: Men 14 killed and 140 wounded

7th lost Officers 1 killed and 10 wounded: Men 52 killed and 187 wounded

11th lost Officers 0 killed and 4 wounded: Men 7 killed and 62 wounded

20th lost Officers 3 killed and 17 wounded: Men 38 killed and 189 wounded

23rd lost Officers 3 killed and 8 wounded: Men 23 killed and 85 wounded

24th lost Officers 0 killed and 0 wounded: Men 0 killed and 1 wounded

7th Royal Fusiliers: Battle of the Pyrenees fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

27th lost Officers 3 killed and 11 wounded: Men 58 killed and 228 wounded

28th lost Officers 1 killed and 6 wounded: Men 9 killed and 11 wounded

29th lost Officers 11 killed and 11 wounded: Men 11 killed and 121 wounded

31st lost Officers 0 killed and 3 wounded: Men 2 killed and 37 wounded

32nd lost Officers 0 killed and 4 wounded: Men 4 killed and 51 wounded

34th lost Officers 1 killed and 5 wounded: Men 48 killed and 122 wounded*

36th lost Officers 0 killed and 3 wounded: Men 8 killed and 35 wounded

39th lost Officers 2 killed and 7 wounded: Men 11 killed and 118 wounded

40th lost Officers 2 killed and 10 wounded: Men 22 killed and 197 wounded

42nd lost Officers 0 killed and 0 wounded: Men 4 killed and 26 wounded

45th lost Officers 0 killed and 1 wounded: Men 0 killed and 7 wounded

48th lost Officers 2 killed and 10 wounded: Men 12 killed and 109 wounded

50th lost Officers 3 killed and 12 wounded: Men 30 killed and 198 wounded

51st lost Officers 0 killed and 0 wounded: Men 7 killed and 62 wounded

53rd lost Officers 0 killed and 1 wounded: Men 1 killed and 20 wounded

57th lost Officers 0 killed and 3 wounded: Men 4 killed and 68 wounded

58th lost Officers 0 killed and 6 wounded: Men 10 killed and 61 wounded

60th lost Officers 2 killed and 6 wounded: Men 8 killed and 72 wounded

61st lost Officers 0 killed and 4 wounded: Men 3 killed and 38 wounded

68th lost Officers 1 killed and 3 wounded: Men 8 killed and 41 wounded

71st lost Officers 2 killed and 7 wounded: Men 28 killed and 181 wounded

74th lost Officers 1 killed and 4 wounded: Men 6 killed and 38 wounded

79th lost Officers 0 killed and 1 wounded: Men 5 killed and 47 wounded

82nd lost Officers 4 killed and 6 wounded: Men 17 killed and 146 wounded

91st lost Officers 0 killed and 7 wounded: Men 13 killed and 100 wounded

92nd lost Officers 0 killed and 26 wounded: Men 55 killed and 363 wounded

95th lost Officers 0 killed and 2 wounded: Men 7 killed and 28 wounded

*The 34th Regiment in the defence of the Rock of Aretesque during the Battle of Maya lost around 80 men as prisoners to the French, including Captain Moyle Sherer.

Battle Honours and Medal for the Battle of The Pyrenees:

The Battle of the Pyrenees is a battle honour for all the British regiments involved: 14th Light Dragoons, 2nd Queen’s, 3rd Buffs, 6th Regiment, 7th Royal Fusiliers, 10th, 11th, 24th, 23rd Royal Welch Fusilier, 27th, 28th, 29th, 31st, 32nd, 34th, 39th, 40th, 42nd Royal Highlanders, 43rd Light Infantry, 45th, 48th, 50th, 51st, 53rd, 57th, 58th, 60th Rifles, 61st, 71st Highland Light Infantry, 74th Highland Light Infantry, 79th Highlanders, 81st, 91st Highlanders, 92nd Gordon Highlanders and 95th Rifles.

The Military General Service Medal for service in the Peninsular War and other areas between 1793 and 1814 (not including the Battle of Waterloo, which had its own medal) was issued with a clasp for Pyrenees, to all those still alive in 1848 who claimed the medal and were entitled to it. No medal was issued without one or more, up to 11, of the 29 battle clasps recognized.

Army Gold Medal:

In 1810 a Gold Medal was issued to be awarded to officers of rank of major and above for meritorious service at certain battles in the Peninsular War, with clasps for additional battles. The ‘Large Gold Medal’ was awarded to generals, the ‘Small Gold Medal’ to majors and colonels, with the medal replaced by a cross where four clasps were earned. The Battle of the Pyrenees was one of the battles.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of The Pyrenees:

- The Battle of Maya was followed by a blazing row between General Stewart and Wellington who blamed the loss of the battle on Stewart’s whimsical departure from his post of duty, leaving his two brigades without direction. Wellington wrote Stewart a stinging letter of rebuke, bringing from Stewart a vigorous letter of protest. Wellington refused to amend his criticism. The affair ended when a letter from the Government in London arrived informing Wellington that Stewart was being made Commander of the Bath and that Wellington was to carry out the investiture.

- Fortescue queries why Hill, who had overall command for this section of the line failed to take over control of the battles at Roncesvalles and Maya. Hill, at his headquarters in Elizondo, appears to have been unaware of the battles taking place.

- In the Battle of Sorauren, first day, Fortescue states that many of the French troops were starving, due to the wholly inadequate supply system and either did not have the strength to climb the steep ridge, or, having done so, did not have the strength to conduct a strenuous fight with the troops they were attempting to attack.

- On the day after the Battle of Sorauren, first day, British and French working parties mingled on the hillside of Ridge A, burying the dead from the battle. In particular the highland soldiers fraternised closely with the French.

- Fortescue states of the Battle of Sorauren, first day; ‘Considering that the strength of the French was practically double that of the Allies [British, Portuguese and Spanish], the action has been by some authorities considered one of the most honourable that is recorded of British troops..’

- Fortescue also states, ‘.. a mountain campaign is essentially a blind affair, and many things are obscure to a commander at the moment which seem very clear when reviewed upon paper a hundred years after the event.’

- The commander of ‘Barnes’ Brigade’ in the Battle of the Pyrenees, later Lieutenant General Sir Edward Barnes served in the Waterloo campaign in 1815 as adjutant general, where he was referred to as ‘our fire eating adjutant general’. Barnes distinguished himself as governor of Ceylon where he carried out many public works and introduced coffee as a crop.

- Captain Moyle Sherer of the 34th Regiment described the defence of the Rock of Aretesque and his capture during the Battle of Maya in his book ‘Recollections of the Peninsula’.

References for the Battle of The Pyrenees:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Storming of San Sebastian

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of San Marcial

42. Podcast on the Battle of the Pyrenees: the battles fought between 25th July and 2nd August 1813 in the western Pyrenees Mountains, during the Peninsular War; Wellington decisively repelling Marshal Soult’s incursion across the border to relieve the French garrisons in Pamplona and San Sebastian: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts