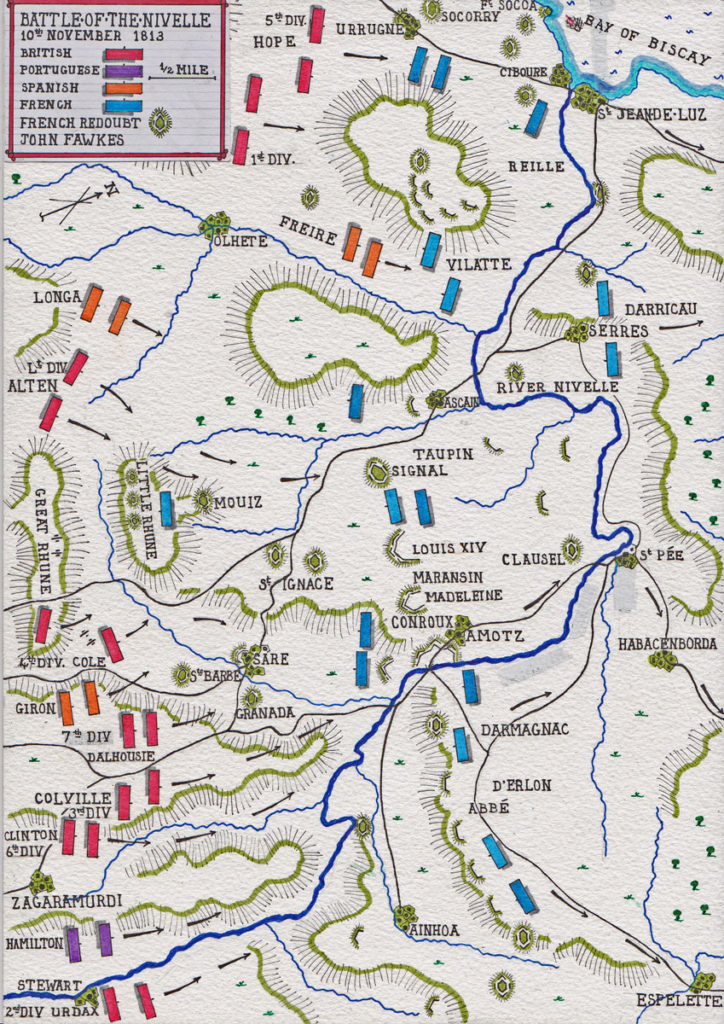

The Battle fought on 10th November 1813, during the Peninsular War; Wellington’s army crossing the River Nivelle and moving from the Pyrenees Mountains into the plains of France

45. Podcast on the Battle of the Nivelle: fought on 10th November 1813, during the Peninsular War; Wellington’s army crossing the River Nivelle and moving from the Pyrenees Mountains into the plains of France: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of the Bidassoa

The next battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of the Nive

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of the Nivelle: 10th November 1813

Place of the Battle of the Nivelle: In the north-east on the Spanish-French border.

Combatants at the Battle of the Nivelle: British, Portuguese and Spanish troops against the French.

Commanders at the Battle of the Nivelle: General the Earl of Wellington against Marshal Soult.

Size of the armies at the Battle of the Nivelle:

Wellington commanded an army of 90,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish troops, not including the troops blockading Pamplona.

Soult commanded 67,000 French troops

Winner of the Battle of the Nivelle: The British, Portuguese and Spanish forced the French back from the River Nivelle to the River Nive and beyond.

Background to the Battle of the Nivelle:

News of the Emperor Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Leipzig on 19th October 1813 brought the British Government to the view that all efforts should now be made to defeat the French and steps were taken to increase the flow of reinforcements for Wellington’s army on the Spanish-French border.

The one restraint on Wellington’s invasion of France was the continued resistance by the French garrison in the City of Pamplona, positioned in his right rear and blockaded by the Spanish troops of Carlos d’España.

With the Pamplona garrison’s supplies exhausted, the French commander, General Cassan, despairing of relief by Marshal Soult, surrendered the city on 30th October 1813.

With the fall of Pamplona and the news from Northern Europe, Wellington considered himself free to continue with his invasion of France.

In addition, Wellington needed to move his army out of the mountains into the plains of France.

The severe winter weather was setting in, the troops in the mountains suffering from exposure with Hill’s Second Division at Roncesvalles in knee-deep snow.

In the meantime, Marshal Soult’s army was building a chain of redoubts to keep Wellington’s troops out of French territory.

Wellington paid daily visits to Alton’s Light Division’s positions on la Grande Rhune to monitor the progress of Soult’s defensive chain.

During one of these visits, Wellington commented to Colborne, the redoubtable colonel of the 52nd Light Infantry and one of Alton’s brigade commanders, that he would overrun the French line with ease because there were not enough French troops to man the length of the defences and Soult could not know where the assault would fall.

Wellington’s attack was delayed by the winter weather, with snow in the mountains and rain at the lower altitudes.

On 4th November 1813, the weather improved and the attack was planned for 8th November 1813, although later delayed.

Wellington’s main assault was to be against the village of Sare, the Light Division and Longa’s Spanish troops storming la Petite Rhune positions at the western end, while Giron’s Spanish took the eastern end.

Cole’s Fourth Division was to attack directly towards Sare, while Colville led the Seventh Division down the Nivelle to take the bridge at Amots, an important link in the French line between Clausel’s Corps in the centre and D’Erlon’s Corps on the French left.

Beresford was to command the formations on the eastern side of la Grande Rhune.

While in the Bidassoa battle the main attack was driven along the sea coast, in the Battle of the Nivelle the coast was the scene for a feint attack, with several divisions committed under the command of Sir John Hope (First and Fifth Divisions, with Portuguese brigades and two cavalry brigades).

A squadron of the Royal Navy under Commodore Collier was to bombard the French fort at Socoa.

A substantial force, comprising the Sixth and Second Divisions with cavalry and Portuguese infantry, was to advance on the extreme right, in the mountains, with Morillo’s Spanish threatening the French flank.

The Battle of the Nivelle:

The improvement in the weather with the noticeable movement of artillery warned Soult that he was about to be attacked.

Soult’s conclusion was that Wellington’s attack would be on his left, centre and right.

Reille’s Corps held the right wing by the sea coast. Clausel’s Corps held the ground from Ascain to the Nivelle River at Amotz, while D’Erlon’s Corps held the ground east of the Nivelle.

In re-arranging his formations, Soult moved Darricau’s Division to Serres and brought Foy’s Division, less a garrison left in St Jean Pied de Port, further west to Biddaray.

Soult also brought forward his brother’s division of dragoons, with a brigade of Treilhard’s dragoons, across the River Nive in support of his entrenched infantry.

Wellington’s attack began at 6am on 10th November 1813, with the feint attack by Hope’s guns and picquets on the French positions at Socorry by the coast.

Soult, after his absence from the Bidassoa attack due to his position at the other end of the line, was on the extreme French right, near the Biscay coast.

Following a heavy bombardment, the British Fifth Division with Stopford’s Guards Brigade, Halkett’s King’s German Legion Brigade and Aylmer’s Brigade attacked the French positioned around Socorry and Urrugne, pushing them back.

Soult felt his personal position to be correct as this seemed to be the point of Wellington’s main attack.

On the right flank of Hope’s force, Freire’s Spanish pushed Vilatte’s Division back towards Ascain.

Vilatte fell back across the River Nivelle and joined Darricau at Serres. These two French divisions remained there facing Freire’s Spanish and took no further part in the battle.

The casualties of each side in this part of the battle are described as ‘trifling’.

The effect of Hope’s feint was to deceive Soult as to the true point of attack and to take four French Divisions out of the battle, pinning them in the coastal area.

In the early hours of 10th November 1813, Alten’s Light Division advanced to la Grande Rhune and prepared to attack the French positions on la Petite Rhune, comprising a series of redoubts.

To the north of la Petite Rhune lay the main redoubt in this part of the line, the Mouiz Redoubt.

A shoulder of the mountain connected the redoubts on la Petite Rhune to the Mouiz Redoubt, lined by a dry-stone wall.

The shoulder was held by battalions of the French 40th and 34th of the Line.

The regiments of the Light Division, the 95th Rifles, the 43rd, the 52nd with the 17th Portuguese launched their assault on the various French positions on and around la Petite Rhune.

The result of the attacks was that the French were driven from all their positions on and around la Petite Rhune and fell back in considerable disorder.

Alten halted his regiments to enable the neighbouring divisions to come up in line with him.

To the right of the Light Division, Cole’s Fourth Division, supported by three horse artillery batteries, advanced on the Sainte Barbe redoubt, promptly abandoned by its French garrison, comprising Barbot’s brigade of Maransin’s Division, which fell back on the St Ignace Redoubts.

The British guns turned their fire on the Granada Redoubt, causing the French garrison to follow their comrades from the Sainte Barbe redoubt.

Cole now advanced on the village of Sare, defended by Rey’s Brigade of Conroux’s Division, with Giron’s Spanish troops enveloping the village from the west and Dalhousie’s Seventh Division from the east.

Further east still, Colville’s Third Division was advancing down the River Nivelle, reaching the bridge at Amots, where Conroux’s second brigade was engaged.

British skirmishers swarmed into Sare and drove the French out.

Maransin was holding the redoubts behind Sare, the Louis XIV and the Madeleine, from where he was compelled to dispatch troops to bolster up the various French positions, until he was forced to withdraw.

In the centre of the French line, Taupin’s Division held the area around Ascain, the Signal Redoubt, the St Ignace Redoubts and the high ground around them.

Clausel reformed Maransin’s and Taupin’s Divisions to cover the area between the Louis XIV Redoubt, the Signal Redoubt and the River Nivelle.

The Light Division now developed a new attack to envelop the French positions around Ascain.

Soon after 10am, the British, Portuguese and Spanish troops advanced up the slope on which stood the Louis XIV Redoubt.

The vigorous advance by Alten’s Light Division caused Taupin to fear that he would be cut off from the French centre around Ascain and Serres. Taupin pulled his troops back from supporting the Louis XIV Redoubt.

Colville’s Third Division launched an assault from the bridge at Amots on Conroux’s Division. The attack was vigorously resisted, until Conroux himself was mortally wounded and his division gave way and retreated down the bank of the River Nivelle, leaving Maransin unsupported.

By 11am, Colville’s Division was well established on the hill to the east of the Louis XIV Redoubt.

French artillery came into action in support of Conroux’s retreating troops, but was in turn silenced by Ross’s troop of horse artillery, which was managing, in spite of the difficult terrain, to keep up with the rapidly advancing British Third Division.

The British Fourth, Seventh and Third Divisions then attacked the Louis XIV Redoubt.

Maransin’s Division was forced out of the redoubt which was stormed and taken with 180 French prisoners.

Briefly taken prisoner, Maransin withdrew his surviving troops from hilltop to hilltop, pressed closely all the way, until he was able to cross the River Nivelle at St Pée.

Taupin’s Division remained at the Signal Redoubt, between Ascain and the Louis XIV Redoubt, expecting support from Darricau’s Division at Serres. Support which did not come.

Taupin now found himself threatened, not only on his left but also by the swiftly advancing Light Division to his front.

The British 52nd Light Infantry, in a spirited advance, at times under artillery fire, reached a concealed point 80 yards from the French positions and in a sudden charge took the whole of the St Ignace Redoubt complex, dispersing the French 70th of the Line, which formed most of the garrison.

While Clausel was trying to organise a counter-attack to retake the St Ignace Redoubts, it became clear that the advances on each side of the redoubt were endangering his line of retreat and that only one road leading to a bridge over the Nivelle was still open.

Clausel’s last move before a general retreat was the extraction of the 88th of the Line from the Signal Redoubt, now under threat by Colborne and the 52nd Light Infantry.

Several French regiments were ordered to support the 88th, but none obeyed, all continuing their precipitate retreat to the Nivelle bridge.

None of the staff officers sent to warn the 88th to withdraw got through.

After several costly attempts to storm the Signal Redoubt, Colborne sent a message to the French commander requiring him to surrender to the British or face capture by the vengeful Spanish troops of Giron. The French commander reluctantly surrendered the Signal Redoubt to Colborne.

The regiments of Clausel’s Corps managed to cross to the north bank of the River Nivelle in various places, using bridges and fords, under heavy pressure from the British, Portuguese and Spanish troops.

During the course of the heavy defeat of Clausel’s Corps by a force four times its size, Marshal Soult initially remained in St Jean de Luz, where he faced only Wellington’s feint attack.

At 10.30am, Soult moved to Serres. Fortescue criticises Soult for failing to send Darricau’s Division to the support of Clausel’s hard pressed corps.

On the French left, the divisions of Darmagnac and Abbé from D’Erlon’s Corps held the fortified line from the bridge at Amots to Ainhoa and into the mountain line to the east of Ainhoa.

Hill’s divisions advanced along the line of the River Nivelle, moving downstream from Urdax, Clinton’s British Sixth Division leading Hamilton’s Portuguese Division and Stewart’s Second Division.

Clinton and Hamilton crossed the River Nivelle and advanced on the main French positions.

After being held up by French artillery fire from his right flank, while he crossed a ridge to reach the main French position, Hamilton was able to follow Clinton’s advance towards the French line.

Stewart came up on the line of the river and crossed to the right bank to take his position for the assault on the Ainhoa line.

Skirmishers from Colville’s Third Division crossed the bridge at Amots, threatening Darmagnac’s right flank in the Ainhoa position.

At around 1pm, Hill launched his attack on the French line, each of his three divisions assaulting one of the redoubts.

As Clinton’s Division rushed the left-hand redoubt, his men suffered considerable casualties before the French abandoned the position.

Hamilton advanced on the next French redoubt to the right, to find that the hutments had been set ablaze making it impossible for his men to enter the area: That is until the grenadier companies and a battalion of caçadores moved around the right-hand end of the fire and stormed the redoubt.

At this point D’Erlon ordered Darmagnac to withdraw to Habacenborda, leaving Abbé’s Division to look after itself, unsupported.

Attacked by Stewart’s Second Division, led by Ashworth’s Portuguese Brigade and Byng’s Brigade, Abbé put up a considerable resistance in defending his redoubt, until, seeing he was left unsupported, he withdrew his division to Espelette.

D’Erlon, on reaching Habacenborda with Darmagnac’s Division, found the village already held by Conroux’s Division and moved further north into France.

On the extreme French left, Foy’s Division drove back the Spanish troops of Mina and Morillo, then judging by the firing that the French Centre had been forced back, Foy joined the general French retreat.

Wellington halted the advance of his army at St Pée, while Hill’s Corps came up in line, which he did at around 5pm.

The British Third and Seventh Divisions crossed the River Nivelle and drove the French out of Habacenborda.

Wellington considered that it was now too late in the day to achieve anything further in the battle and did not intend any further advance.

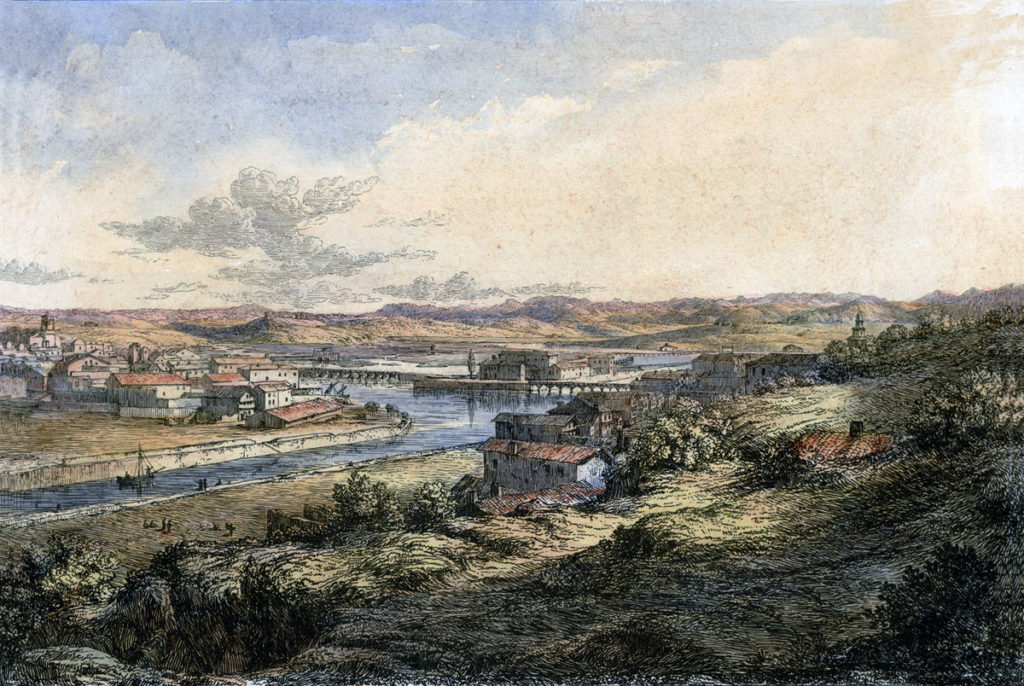

Soult however still felt threatened and ordered Reille to withdraw across the Nivelle, destroying the two bridges at St Jean de Luz and take up positions on the heights of Bidart, some miles back.

The divisions of Clausel’s and D’Erlon’s Corps also fell back, leaving only Darmagnac and Foy in positions at Ustaritz and Cambo.

On 12th November 1813 Wellington intended to launch another assault, but Soult pulled further back towards Bayonne.

Hill attempted to attack Foy in the area of Cambo, but dense fog and heavy rain, making the Nive River at Cambo impassable, brought Hill’s attack to a halt.

The Battle of the Nivelle ended with Wellington’s army established in France.

Casualties at the Battle of the Nivelle:

French losses in the battle were 4,300 killed, wounded and captured. Of these, 2,700 were lost by Clausel’s three divisions.

The French lost 69 guns.

The British, Portuguese and Spanish suffered 2,700 men killed, wounded and captured.

Casualties were particularly heavy in the British Light Division.

The Aftermath to the Battle of the Nivelle:

Wellington considered the battle to have been unsuccessful. His expectation was that the attack on Clausel would have been decisive and enabled him to cut off the retreat of Reille’s Corps.

Wellington’s attack was held up by the intervention of D’Erlon, although hesitant and indecisive, leaving insufficient daylight to press his attack.

Wellington was still concerned as to the permanence of the alliance against Napoleon. He was also worried by the hostility of the Spanish government to him and was not prepared to risk a reverse.

Battle Honours and Medal for the Battle of the Nivelle:

The Battle of The Nivelle is a clasp on the 1847 General Service Medal.

The Battle of the Nivelle is a battle honour for the following British regiments: 2nd Queen’s, 3rd Buffs, 5th, 6th, 11th, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 24th, 27th, 28th, 29th, 31st, 32nd, 34th, 39th, 40th, 42nd Royal Highland Regiment, 43rd Light Infantry, 45th, 48th, 49th, 51st, 52nd Light Infantry, 53rd, 57th, 58th, 59th, 60th Rifles, 61st, 66th, 68th, 76th, 79th Cameron Highlanders, 82nd, 83rd, 84th, 85thLight Infantry, 87th, 91st Highlanders, 94thand 95th Rifles.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of the Nivelle:

- The 52nd Light Infantry suffered 240 killed and wounded in the Battle of the Nivelle, principally in the attack on the Signal Redoubt. Of these casualties, 100 lightly wounded light infantryman refused to seek treatment and appeared on parade on the following day.

References for the Battle of the Nivelle:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of the Bidassoa

The next battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of the Nive

45. Podcast on the Battle of the Nivelle: fought on 10th November 1813, during the Peninsular War; Wellington’s army crossing the River Nivelle and moving from the Pyrenees Mountains into the plains of France: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts