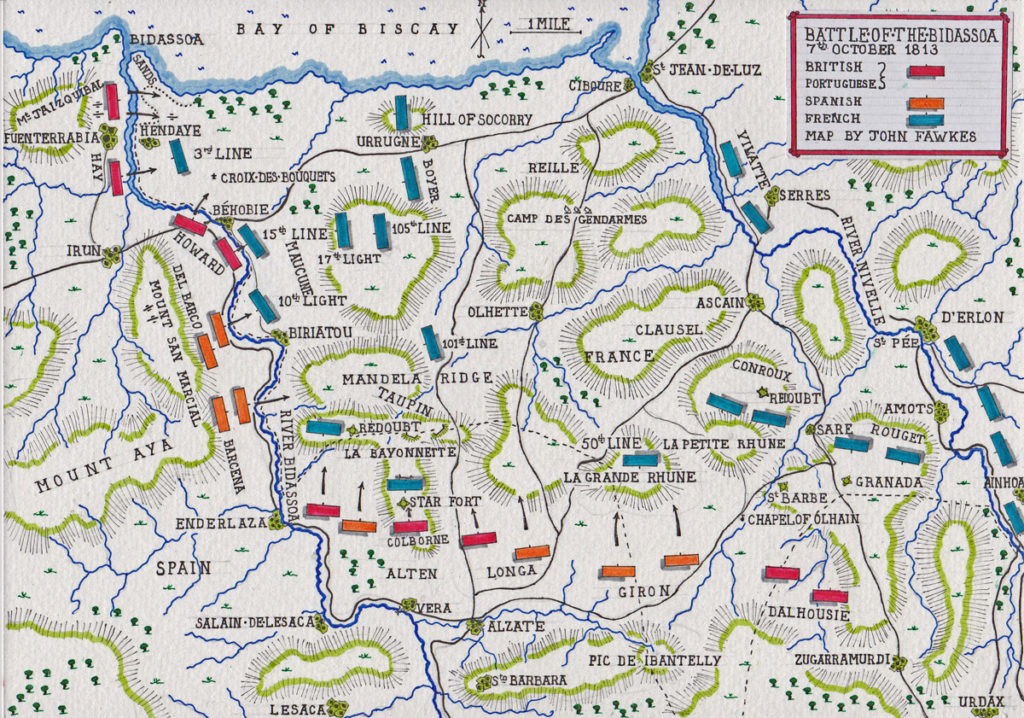

The Battle fought on 7th October 1813, during the Peninsular War; Wellington’s army crossing the River Bidassoa into France

44. Podcast on the Battle of the Bidassoa fought on 7th October 1813 during the Peninsular War with Wellington’s army crossing the River Bidassoa into France: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of San Marcial

The next battle in the British Battles Sequence is the Battle of the Nivelle

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of the Bidassoa: 7th October 1813

Place of the Battle of the Bidassoa: In the north-east of Spain on the French border.

Combatants at the Battle of the Bidassoa: British, Portuguese and Spanish troops against the French.

Commanders at the Battle of the Bidassoa: General the Earl of Wellington against Marshal Soult.

Size of the armies at the Battle of the Bidassoa:

Wellington commanded an army of 80,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish troops.

Soult commanded 70,000 French troops of which 5,000 held the advanced positions along the Bidassoa River and around 45,000 were actively involved in the battle.

Winner of the Battle of the Bidassoa: The British, Portuguese and Spanish forced the French back from the River Bidassoa.

Background to the Battle of the Bidassoa:

At the end of 1813, after the successes of the Battle of the Pyrenees and the Storming of San Sebastian, Wellington was poised to invade France.

Wellington held back from invading France because he did not trust the coalition of states, Russia, Prussia, Austria, Sweden and others, coalescing against the Emperor Napoleon in northern Europe, to achieve victory against the French or even to remain together.

Wellington feared that, in the event of a collapse of the coalition, Napoleon would turn his forces on Wellington’s army, particularly if it had invaded France.

In addition, the Spanish city of Pamplona, held by the French, although under blockade, stood near to Wellington’s lines of communication into Spain.

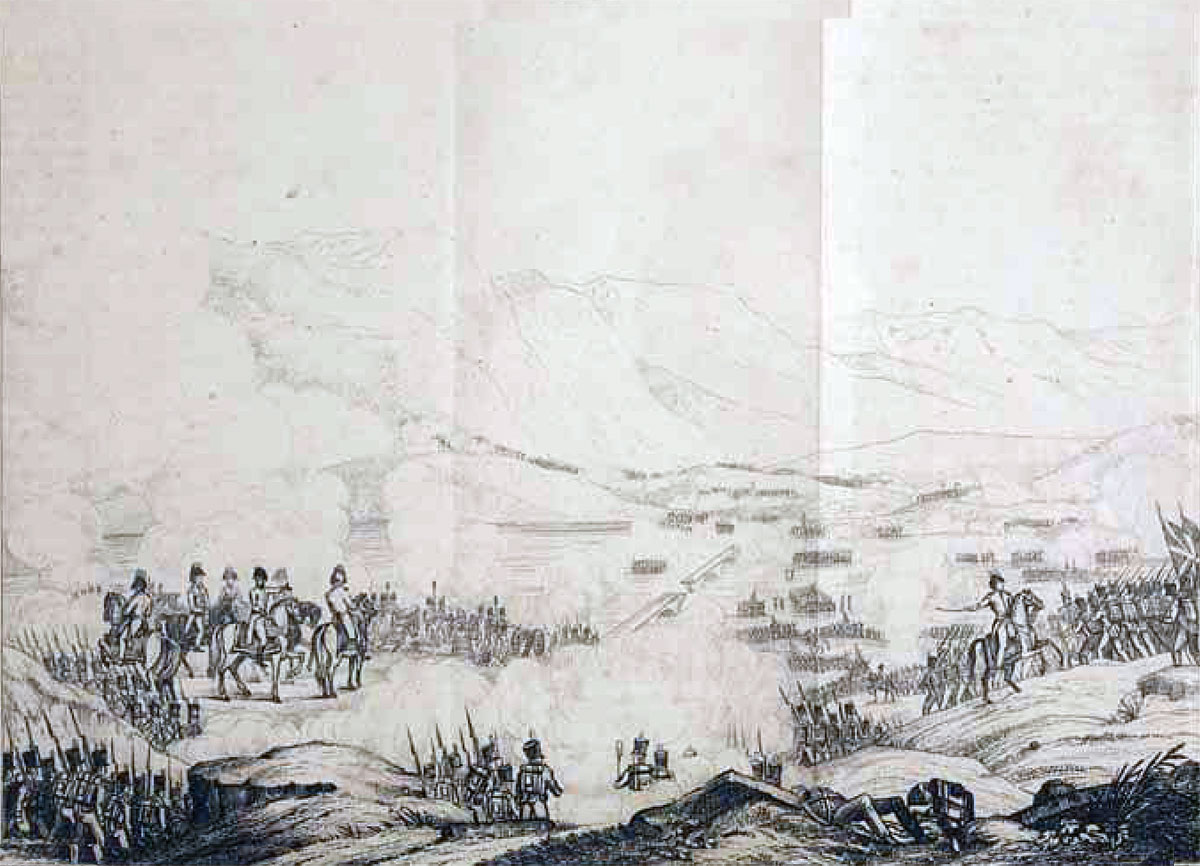

British Army crossing the Bidassoa at the Battle of the Bidassoa on 7th October 1813 during the Peninsular War: drawing by eye-witness William Graham

News of the series of victories against Napoleon in northern Europe, forcing the French armies back into France, began to reach Wellington in early to mid-September 1813.

There were clear indications of a Royalist rising in France, ready to ally itself with Wellington’s army once it crossed the border.

In mid-September 1813, Wellington decided to force the line of the River Bidassoa and invade France.

Soult’s Deployment:

Marshal Soult’s French army on the River Bidassoa comprised the corps of Reille, Clausel and D’Erlon.

Following the unsuccessful Battle of San Marcial, these formations returned to the positions they held before the attack.

On the French right, Reille’s Corps deployed with Boyer’s Division (late Lamartinière’s) holding Urrugne, Maucune’s Division holding the positions around Croix des Bouquets and Villatte’s Division around Serres.

In the French centre was Clausel’s Corps, with Conroux’s and Rouget’s (late Vandermaesen’s) Divisions holding Sare and Taupin’s Division on the Heights of La Bayonette.

On the left, the divisions of D’Erlon’s Corps, Darmagnac’s, Abbé’s and Maransin’s Divisions, were positioned around Ainhoa.

Foy’s Division again occupied St Jean Pied de Port.

The morale of the French troops was low, with their repeated defeat in battle, the continuous rain and lack of supplies.

Due to the shortage of forage for the horses, Soult was forced to pull his cavalry and most of his artillery behind the River Adour, some 15 miles behind his front line.

The French infantry spent their time fortifying their positions and waiting to be attacked.

The Battle of the Bidassoa:

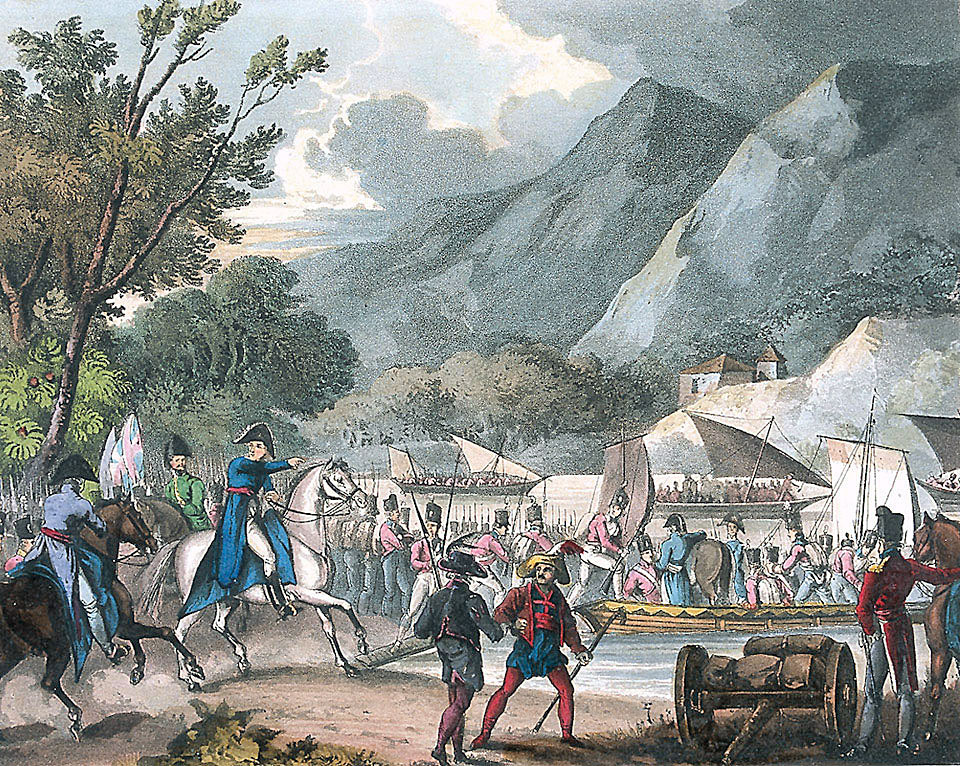

As soon as Wellington’s army captured San Sebastian on 9th September 1813, the order was given for the pontoon train to advance to Oyarzun for a crossing of the estuary of the River Bidassoa and an attack on the French positions on the east bank.

While the pontoon train made its slow journey, Wellington’s officers reconnoitred routes across the estuary, assisted by local fishermen.

On 1st October 1813, Campbell’s Portuguese Brigade attacked the French at Aldudes, in the Baigorry Valley at the eastern end of the French line and drove them back with the loss of 40 men and 2,000 sheep.

The activities to the east caused Soult anxiety, but his real concern arose when he heard from a deserter on 14th September 1813 that Wellington’s pontoon train was moving along the coastal road towards the River Bidassoa.

Wellington resolved to launch his attack on 7th October 1813.

On 6th October 1813, Hill marched his Portuguese division from the valley of Baigorry into the valley of Baztan, releasing Picton’s Division to move to Atchuria, and in turn Dalhousie’s Division to move to Echalar.

On the evening of 6th October 1813, heavy rain storms broke.

In the early hours of 7th October 1813, Wellington’s troops assembled under arms and began their march to the Bidassoa Estuary, their movements concealed by the driving rain.

At 7am, General Hay’s British Fifth Division, marched through Fuentarrabia on the west bank of the Bidassoa Estuary and began its crossing of the Bidassoa in three columns; Greville’s Brigade on the right, the Portuguese Brigade in the centre and Hay with Robinson’s Brigade, two squadrons of the 12th Light Dragoons and two batteries of artillery on the left.

A single French battalion from the 3rd Line guarded the lower estuary of the Bidassoa.

The crossing was not easy, the water at times coming up to the British and Portuguese infantrymen’s armpits.

As Hay’s division reached the sandbank in the centre of the Bidassoa Estuary, a rocket fired from Fuenterrabia announced the beginning of Wellington’s assault and the batteries on San Marcia opened fire on the French lines.

Only then did the French realise they were under attack and opened fire across the river.

On reaching the French shore, Hay’s left column drove the French battalion back and advanced, swinging well to the left to outflank the French positions.

Further upstream, Howard’s British First Division crossed the River Bidassoa by fords above and below Behobie, covered by the fire of the three batteries positioned on Mount San Marcial.

Reille ordered Boyer’s 9th Division to assemble and march from Urrugne to reinforce Maucune’s 3rd, facing the irruption of British and Portuguese troops across the Bidassoa River.

By the time the body of Boyer’s 9th Division began to arrive, the battalions of the 3rd Division, with the limited reinforcements sent in advance, were being forced back by Hay’s and Howard’s divisions.

The French, after a disorderly retreat, with some of their guns only extricated with difficulty, took up a defensive line on either side of the main road to the east of Urrugne, stretching from the Hill of Socorry in the north to the Camp des Gendarmes in the south.

A number of additional French regiments, 2nd and 10th Light and 119th and 101st of the Line, driven back from around Biriatou by Freire’s Spanish Divisions, joined Reille’s position east of Urrugne.

Hay and Howard halted on the high ground on the right bank of the River Bidassoa, although parties of skirmishers penetrated into Urrugne, to be driven back by the French.

The attacking columns captured a French battery of 4 heavy guns near the mouth of the estuary and 7 other field guns along the line of the River Bidassoa.

While the attack was carried out on the French right by the columns crossing the Bidassoa Estuary, the divisions of Alten, Longa and Giron were advancing in the centre, where they faced Clausel’s Corps; Conroux north of Vera, Taupin on the Heights of La Bayonette and Maransin on the left.

The French 50th of the Line held the feature, La Grande Rhune.

Observing that Giron’s troops were threatening the position, Clausel ordered Maransin to re-inforce the 50th with the 34th of the Line.

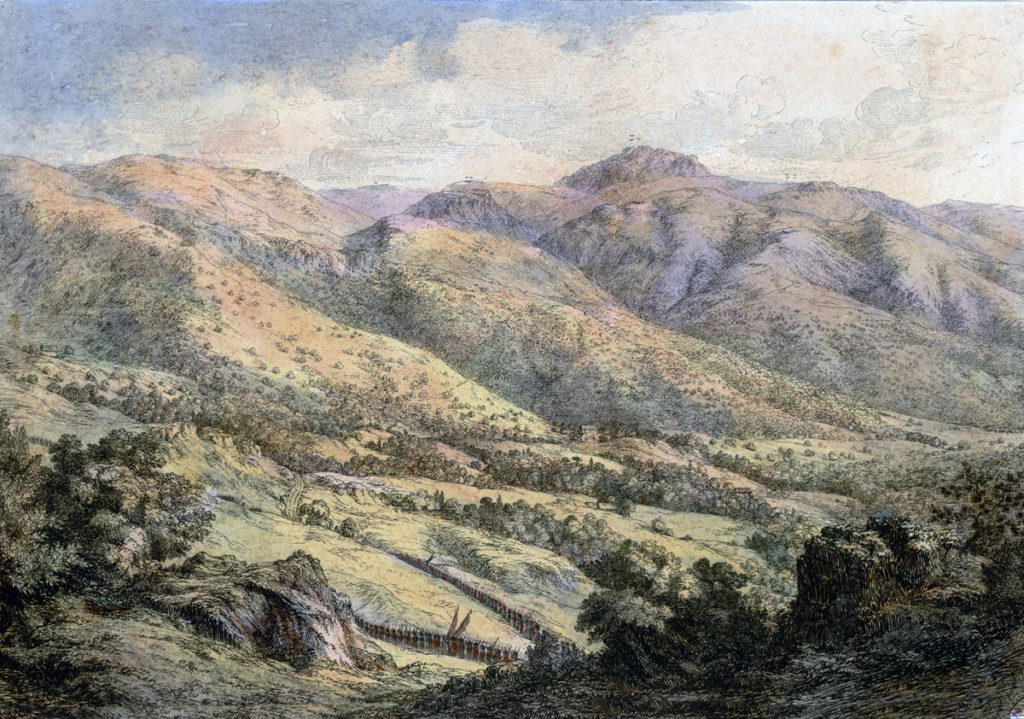

Alten and Giron resolved to launch a joint attack on La Bayonette, a mountainous feature on the right bank of the Bidassoa, held by 4 companies of the French 31st of the Line.

At 7am, five companies of the 3rd/95th Rifles with 17th Portuguese attacked the western end of La Bayonette, while a Spanish battalion attacked the eastern end, clearing the French off the flanks of the hill.

The rest of Kempt’s Brigade joined these forces on the hillside, while Colborne’s Brigade of the Light Division attacked the entrenched redoubts, one main and three subsidiary, on La Bayonette.

Colborne divided his troops into three columns for the attack.

Colborne led the main attack by his own regiment, 52nd Light Infantry, in the centre, while the Rifles and 3rd Cacadores attacked the left and the 1st Cacadores the right.

The French drove the Rifles and 3rd Cacadores down the hill, but on encountering the 52nd, were driven back and out of their redoubt, which the 52nd stormed out of hand.

Colborne then captured the other three redoubts. Coming up to La Bayonette itself, Colborne was held up for some time by the fierce resistance of the French infantry, supported by a mountain battery, before storming the position, capturing three guns and driving the French down the hillside into France.

Seeing some French troops drawn up on the hillside, Colborne, who was a considerable distance ahead of his brigade and accompanied only by his staff, ordered the French officer to hand over his sword and surrender, which the French officer did. Colborne kept this body of French troops in awe long enough for his own men to come up and secure them, making prisoner 22 officers and 400 soldiers.

On the right, Kempt and Longa, with some difficulty, fought forward through the thorny scrub and drove Taupin’s Division out of its positions, forcing the French back to La Grande Rhune.

At 4pm Giron launched an attack with his Spanish Division to drive the French off La Grande Rhune.

Clausel was in the Hermitage on La Grande Rhune, with several battalions of his corps displaced by the capture of positions along the line, particularly La Bayonette.

These troops repelled Giron’s attack.

East of La Grande Rhune, Conroux’s Division was kept motionless by the threatening presence of Dalhousie’s Seventh Division.

On Wellington’s extreme right, Colville’s Third Division held down Darmagnac’s Division and kept the attention of D’Erlon’s three divisions, preventing them from assisting their comrades in the French centre and right.

At the beginning of the battle, Marshal Soult was in Ainhoa on a tour of inspection. Hearing the British bombardment, Soult galloped off to the north-west, arriving in Urrugne at 1pm, with the battle already lost and Wellington over the River Bidassoa.

Action on 8th October 1813:

The British, Portuguese and Spanish encamped on the ground they had won.

There was no fighting on the morning of 8th October 1813, due to a heavy fog.

Once the fog cleared, Giron attacked the French posts in the Chapel of Olhain.

Dalhousie’s light companies threatened the redoubts of Sainte Barbe and Granada, south of Sarre and Colville threatened the bridge over the River Nivelle at Amoto.

Along the line, the French continued to withdraw, abandoning La Grande Rhune and pulling back to the village of Sare, which they held against an attack by skirmishers from Dalhousie’s Seventh Division.

With Wellington’s resolution not to advance further at this stage, the battle petered out.

Casualties at the Battle of the Bidassoa:

In the attack on the estuary of the River Bidassoa, British/Portuguese casualties were 280 killed or wounded and Spanish casualties in the more arduous climb of the Mandela Heights, across the river from San Marcial, were some 300 killed or wounded.

Reille’s Corps suffered 400 killed or wounded. In Fortescue’s view this small casualty level arose from the inadequacy of the French strength along the estuary, 5,000 French troops facing attack across the Bidassoa Estuary by 15,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish.

In the attacks on La Bayonette, Colborne’s 52nd Light infantry suffered 82 killed and wounded and the 2nd/95th Rifles suffered 102 killed and wounded. Portuguese casualties were fewer.

Taupin’s Division, 4,600 strong at the start of the battle, suffered casualties of 350 killed and wounded and 500 taken prisoner.

The Battle of the River Bidassoa cost the French 1,654 killed, wounded and captured and 10 guns.

British, Portuguese and Spanish casualties overall were of the same order, with half of the casualties being Spanish.

The Aftermath to the Battle of the Bidassoa:

Fortescue’s judgment on the Battle of the Bidassoa was ‘..the movement which outwitted Soult and all his subordinates was the fording of the estuary, arm-pit deep, which they had left out of all their calculations as impossible. Considering the extreme delicacy and hazard of this passage, the complete surprise of the French commanders from the highest to the lowest, and the perfect concert in the working of every column of the Allies over a wide front in an extremely blind and difficult country, the passage of the Bidassoa must be ranked among the most masterly, both in conception and execution, of all Wellington’s operations.’

The impact of the battle on Soult’s army was significant. The French troops considered they had been defeated and further lost confidence that they could defeat Wellington’s army.

Men of all ranks up to general seized upon the slightest wound as an excuse to leave the ranks.

French troops turned to plundering the countryside. There was nothing unusual in this for a French army, except that they were now in France.

Marshal Soult took harsh measures in an attempt to control the plundering.

Battle Honours and Medal for the Battle of the Bidassoa:

The Battle of The Bidassoa is not a battle honour for British regiments, nor is it a clasp on the 1847 General Service Medal.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of the Bidassoa:

- During Giron’s attack on Taupin’s Division, a British staff officer, Lieutenant William Havelock, arrived with a message for the Spanish general. Seeing the French in position behind an abattis, Havelock called to the Spanish troops to follow, rode at the abattis and jumped it. The Spanish troops followed him, storming the abattis and driving the French back to La Grande Rhune. William Havelock, the brother of Henry Havelock, who relieved Lucknow, fought in the Indian Mutiny.

- In repelling Giron’s attack on La Grande Rhune, Clausel’s men rolled huge stones down the side of the mountain onto the climbing Spanish troops.

- Robert Batty, whose pictures are shown above, served as an officer in the 1st Foot Guards in the Western Pyrenees and was wounded at the Battle of Waterloo. Batty took a degree in medicine at Gaius College, Cambridge in 1813, before joining the army. A talented artist, Batty toured Europe, after leaving the army, executing sketches and pictures of various landmarks and cities, publishing books and becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society. Batty wrote and illustrated accounts of the campaigns he experienced.

References for the Battle of the Bidassoa:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of San Marcial

The next battle in the British Battles Sequence is the Battle of the Nivelle

44. Podcast on the Battle of the Bidassoa fought on 7th October 1813 during the Peninsular War with Wellington’s army crossing the River Bidassoa into France: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts