Wellington’s hard-fought battle to prevent Massena relieving the fortress of Almeida on 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

British Light Division withdrawing across the plain at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by J.J. Jenkins

21. Podcast of the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro: Wellington’s hard-fought battle to prevent the French Army of Portugal under Marshal Massena relieving the fortress of Almeida on 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Sabugal

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Albuera

Battle: Fuentes de Oñoro

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro: 3rd to 5th May 1811

Place of the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro: on the Spanish-Portuguese border, west of Ciudad Rodrigo.

Combatants at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro: British, Portuguese and Spanish army against the French ‘Army of Portugal’.

Commanders at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro: Lieutenant General Viscount Wellington against Marshal André Massena, Prince of Essling and Duke of Rivoli.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro: 37,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish troops (1,500 being cavalry) with 48 guns, against 48,000 French troops (4,500 being cavalry) and 46 guns.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro:

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers, and stovepipe shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments wore dark green jackets and trousers.

Marshal André_Masséna, Duc de Rivoli, Prince D’Essling: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd -5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Renault

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

Highland regiments wore the kilt with red tunics and black ostrich feather caps.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light cavalry was increasingly adopting hussar uniforms, with some regiments changing their titles from ‘light dragoons’ to ‘hussars’.

The King’s German Legion (KGL) was the Hanoverian army in exile. The KGL owed its allegiance to King George III of Great Britain, as the Elector of Hanover, and fought with the British army. The KGL comprised both cavalry and infantry regiments. KGL uniforms mirrored the British.

The Portuguese army uniforms increasingly during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

The Spanish army essentially was without uniforms, existing as it did in a country dominated by the French. Where formal uniforms could be obtained, they were white.

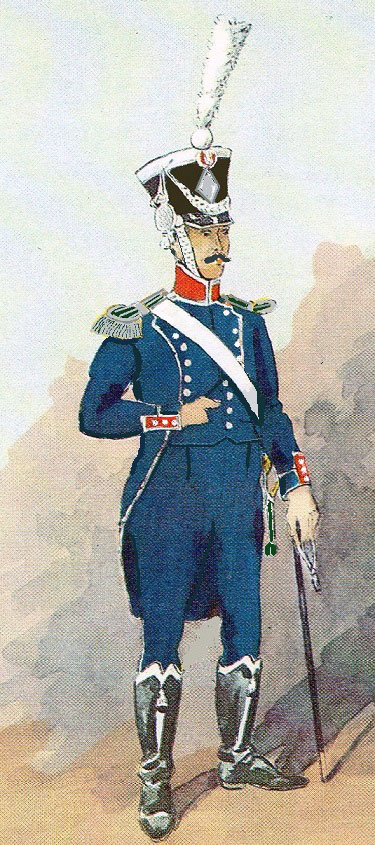

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, although no French cuirassiers served in the Peninsula, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe, and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry, the horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket. The musket could be fired at three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for a hundred metres or so. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, which fitted the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, with a sword bayonet.

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who invented it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was not able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create his powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns with the speed of the French columns of infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

Winner: The British, Portuguese and Spanish, although after the battle, Brennier’s French garrison in Almeida escaped, largely negating the purpose of the battle.

Officer of the British 14th Light Dragoons: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

British order of battle at the Battle

of Fuentes de Oñoro:

Commander: Lieutenant General Viscount Wellington

Cavalry: commanded by Major General Stapleton Cotton

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Slade: 1st Royal

Dragoons and 14th Light Dragoons.

2nd Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant Colonel von Arentschildt:

16th Light Dragoons and 1st Hussars, King’s

German Legion.

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Barbacena: 4th and

10th Portuguese Dragoons.

Infantry: commanded

by Lieutenant General Spencer

1st Division: commanded by Major General Nightingall

1st Brigade: commanded by Colonel Stopford: 1st Coldstream

Guards, 1st/3rd Guards, 1 company 5th/60th Rifles.

2nd Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant General Lord Blantyre: 2nd/24th Foot,

2nd/42nd Foot, 1st/79th Foot,

1 company 5th/60th Rifles.

British Royal Horse Artillery: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Hamilton Smith

3rd Brigade: commanded by Major

General Howard: 1st/50th Rifles, 1st/71st Foot,

1st /92nd Foot, 1 company 5th/60th Rifles.

4th Brigade: commanded by Major General Sigismund, Baron Löw: 1st,

2nd, 5th, 7th Line Battalions, King’s

German Legion, Detachments of Light Battalions, KGL.

3rd Division:

commanded by Major General Thomas Picton.

1st Brigade: commanded by Colonel Mackinnon: 1st /45th Foot,

1st/74th Foot, 1st/88th Foot,

3 companies 5th/60th Rifles

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Colville: 2nd/5th Foot,

2nd/83rd Foot, 2nd/88th Foot,

94th Foot

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Colonel Manley Power: 1st and

2nd/9th, 1st and 2nd/21st Portuguese

Line Regiments

5th Division: commanded by Major

General Sir William Erskine

1st Brigade: commanded by Colonel Hay: 3rd/1st Foot,

1st/9th Foot, 2nd/38th Foot,

company of Brunswick Oels

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Dunlop: 1st/4th Foot,

2nd/30th Foot, 2nd/44th Foot,

company Brunswick Oels

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Spry: 1st and

2nd/3rd and 1st and 2nd/15th Portuguese

Line Regiments, 8th Caçadores

6th Division: commanded by Major General

Alexander Campbell

1st Brigade: commanded by Colonel Hulse: 1st/11th Foot,

2nd/53rd Foot, 1st/61st Foot,

1 company 5th/60th Rifles

2nd Brigade: commanded by Colonel Robert Burne: 1st/36th Foot

(2nd Foot at Almeida)

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Frederick, Baron Eben: 1st and

2nd/8th Foot, 1st and 2nd/12th Portuguese

Line Regiments

7th Division: commanded by Major

General John Houston

1st Brigade: commanded by Brigadier John Sontag: 2nd/51st Foot,

85th Foot, Chasseurs Britanniques, Brunswick Oels Light

Infantry (8 companies)

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General John Doyle: 1st and

2nd/7th and 1st and 2nd/19th Portuguese

Line Regiments, 2nd Caçadores

Light Division: commanded by Brigadier General

Robert Craufurd

1st Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Sydney Beckwith: 1st/43rd

Foot, 1st/95th Rifles (4 companies), 2nd/95th Rifles

(1 company), 3rd Caçadores

2nd Brigade: commanded by Colonel George Drummond: 1st/52nd Foot,

2nd/52nd Foot, 1st/95th Rifles

(4 companies), Portuguese Brigade: 1st and 3rd Caçadores

Independent Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Colonel Ashworth: 1st and 2nd/6th, 1st and 2nd/18th Portuguese Line Regiments

Artillery: commanded

by Brigadier General Howorth, 48 guns

Troops of Ross and Bull, Royal Horse Artillery

Batteries of Lawson and Thompson

Portuguese batteries of Von Arentschild, da Cunha and Rozierres.

French Artillery and Train of the Imperial Guard: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd -5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Belangé

French order of battle at the Battle of

Fuentes de Oñoro:

Army of Portugal:

Commander-in-Chief: Marshal André Massena, Prince

of Essling and Duke of Rivoli

II Corps: commanded by General Reynier

1st Division: commanded by General Merle

2nd Division: commanded by General Heudelet

Cavalry Brigade: commanded by General Soult

VI Corps: commanded by General Loison

1st Division: commanded by General Marchand

2nd Division: commanded by General Mermet

3rd Division: commanded by General Ferey

Cavalry Brigade: commanded by General Lamotte

VIII Corps: commanded by General Junot, Duke of

Abrantes

2nd Division: commanded by General Solignac

IX Corps: commanded by General Count d’Erlon

1st Division: commanded by General Claparède

2nd Division: commanded by General Conroux

Cavalry Brigade: commanded by General Fournier

Reserve of Cavalry: commanded by General Montbrun

Artillery: commanded by General Eblé: 40 guns

Army of the North:

Commander-in-Chief: Marshal Bessières, Duke of Istria

Cavalry of the Imperial Guard: commanded by General Lepic

Light Cavalry Brigade: commanded by General Wathier

Artillery: 6 guns.

General Lepic leading the Horse Grenadiers of the Imperial Guard at the Battle of Eylau: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

Background to the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro:

Following the winter of 1810, spent by Marshal Massena’s Army of Portugal before the lines of Torres Vedras, the French retreated into Spain, leaving a garrison in the Portuguese border fortress of Almeida.

Wellington followed the French withdrawal with his British and Portuguese army and blockaded Almeida, which had to be taken before he continued his advance into Spain. Wellington was there joined by several Spanish guerrilla bands.

In April 1811, Massena assembled his Army of Portugal for an advance to relieve the French garrison in Almeida.

Northern Spain was under the control and command of the French Marshal Bessières.

Massena addressed repeated requests to Bessières to provide him with the supplies and ammunition his Army of Portugal needed after its disastrous retreat from before Lisbon.

While promising a great deal, Bessières failed to satisfy Massena’s needs.

On 1st May 1811, Bessières joined Massena’s army, bringing two brigades of cavalry and six guns, far below Massena’s expectations or what Bessières had promised.

On 2nd May 1811, Massena’s army crossed the River Agueda at Ciudad Rodrigo and advanced towards Almeida, the British cavalry and Light Division retiring before him.

Wellington devised a plan to confront the French in a major battle to cover his blockade of Almeida.

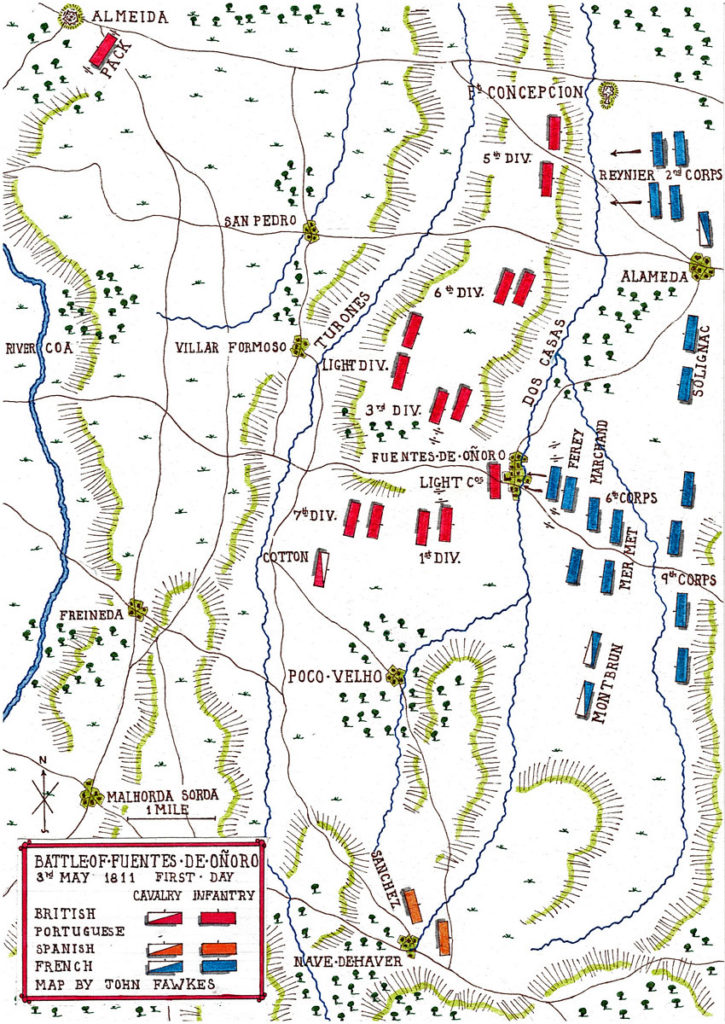

The position Wellington chose was based on Fuentes de Oñoro, a village on the north-south running stream of Dos Casas on the Portuguese-Spanish border.

Parallel to the Dos Casas and 3 miles to its west ran the stream of Turones with a ridge running between the two streams.

4 miles to the south of Fuentes de Oñoro lay the village of Poco Velho, in an area of flatter ground, covered in forest and scrub.

A further 3 miles to the south was the village of Nave de Haver, both these villages lying on the Dos Casas stream.

In the morning of 3rd May 1811, Massena began his advance, the French Second Corps marching towards Alameda, 5 miles to the north of Fuentes de Oñoro, Solignac’s Division approaching to the north of Fuentes de Oñoro and the Sixth Corps and Montbrun’s Cavalry, supported by the Ninth Corps, to the south of Fuentes de Oñoro.

Behind Massena’s army moved the convoy of supplies for the garrison in Almeida.

French Officer and Fusilier of the Line: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

Wellington detached a force to continue the blockade of Almeida, comprising Pack’s Portuguese Brigade, a regiment of Portuguese cavalry, a British battalion and two guns and deployed the rest of his army on the Fuentes de Oñoro position.

Wellington, with the French columns in sight, disposed his troops with the Fifth Division to the south of Fort Concepcioun, the fortification that covered the road to Almeida, 3 miles north-west of Alameda.

The Sixth Division was positioned to the right of the Fifth.

Wellington placed his right in the key village of Fuentes de Oñoro.

Fuentes de Oñoro was garrisoned by 28 light companies from the battalions of the First and Third Divisions, other than the Foot Guards, some 2,000 men commanded by Colonel Williams of the 95th Rifles.

Behind Fuentes de Oñoro were positioned the British First, Third and Seventh Divisions.

The only troops covering the flat ground to the south of Fuentes de Oñoro were the small number of Spanish guerrilla troops commanded by Julian Sanchez.

The Light Division was in reserve behind Fuentes de Oñoro, with the British cavalry on its right.

Account of the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on 3rd May 1811:

Officer 79th Cameron Highlanders: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

Massena, accompanying the Sixth Corps, decided that the principal French attack should be on the village of Fuentes de Oñoro and that it should be carried out by Ferey’s Division of 10 battalions, while Reynier made a feint on Fort Concepcion.

Wellington ordered the Light Division to march to the left to counter Reynier’s move, before he realised it was not a substantive attack and called it back.

Throughout the battle, both on the 3rd and 5th May 1811, Fuentes de Oñoro was the scene of heavy fighting, as the French strove to capture the village and the British battalions fought to drive them back.

Ferey’s first brigade attacked Fuentes de Oñoro and drove the British light companies up through the village to the walled church.

Williams counter attacked with his reserves and pushed the French back through the village.

Ferey committed his second brigade to the attack, made at two points on the village edge and drove the British back again, Williams being seriously wounded.

To restore the situation in Fuentes de Oñoro, Wellington despatched two Scottish regiments, the 71st Highland Light Infantry and the 79th Cameron Highlanders, with the 24th in support.

The 71st, led by Colonel Cadogan, charged through Fuentes de Oñoro and forced the French back, taking many prisoners.

Four battalions from Marchand’s Division were committed to Fuentes de Oñoro to repel the British counter-attack, but, by nightfall, the French held only a few buildings on the eastern side of the Dos Casas stream.

79th Cameron Highlanders attacking the village of Fuentes de Oñoro during the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on 3rd May 1811 in the Peninsular War

Fighting was suspended and the casualties of each side recovered.

British casualties in the fighting in Fuentes de Oñoro on that day were 259, while the French lost 652 killed, wounded or captured, 160 of them being prisoners of the British.

The French assault had been a failure and Massena realised that he had attacked at the wrong point.

On the morning of 4th May 1811, Montbrun conducted a reconnaissance of the area to the south of Fuentes de Oñoro and discovered that the only troops positioned there were Julian Sanchez’s guerrilla bands.

On this basis, Massena made his plans for a further attack the next day, 5th May 1811.

Reynier would repeat his feint against Fort Concepcion on Wellington’s left wing and Ferey was to threaten a further attack on Fuentes de Oñoro.

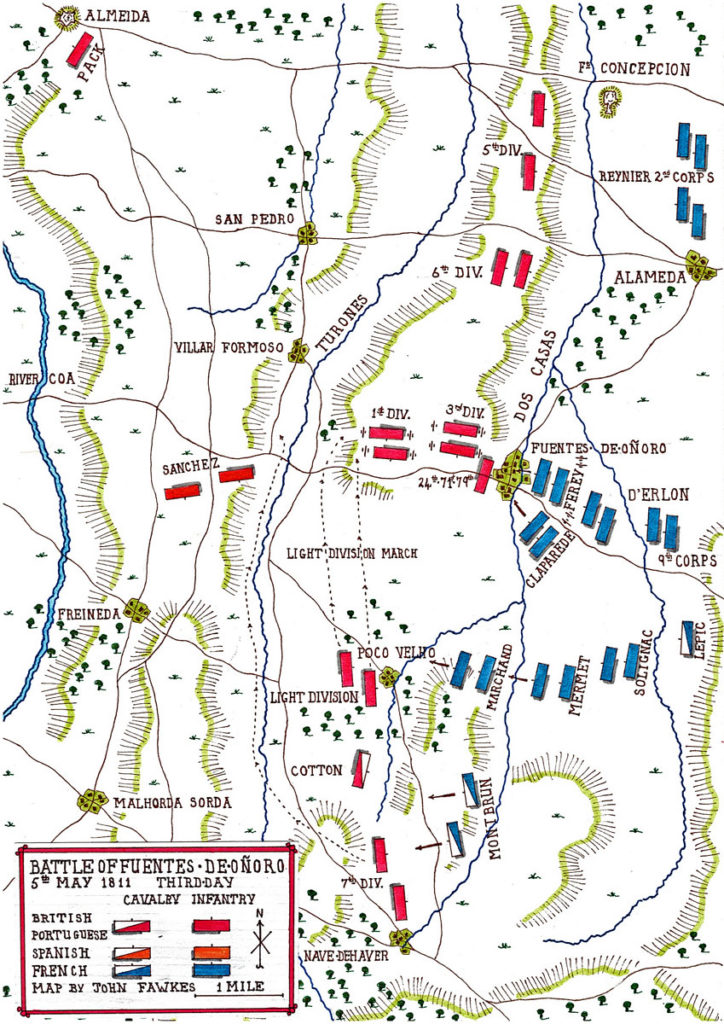

The Ninth Corps was to spread out to cover the area previously occupied by the Sixth Corps, which was to launch an assault around Wellington’s vulnerable right.

Mermet’s and Marchand’s Divisions, supported by Solignac’s Division, were to attack Poco Velho beyond Wellington’s right flank, while the cavalry of Montbrun’s Division and the brigades of Fournier and Wathier advanced through Nave de Haver even further to the south.

Wellington was able to observe Massena’s reconnaissance and its implications and was urged by Spencer to reinforce his right wing.

The British Seventh Division, only recently arrived in the army, was detached to the hill overlooking Poco Velho to defend the crossing of the Dos Casas stream.

General Houston occupied Poco Velho and the neighbouring wood with the 85th and the 2nd Caçadores and positioned his other regiments, the Chasseurs Britanniques and the Brunswick Oels Light Infantry, in the plain towards Nave de Haver.

The British light companies were withdrawn from Fuentes de Oñoro and replaced by the 71st and 79th regiments, with the 24th in support.

The Light Division moved back to the centre at the rear.

The length of Wellington’s line was now 12 miles.

On the evening of 4th May 1811, Robert Craufurd arrived back from England and resumed command of the Light Division, to the delight of all ranks and nationalities in the division.

Account of the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on 5th May 1811:

Early on 5th May 1811, Wellington observed a large body of French infantry and cavalry moving south towards his extreme right, the French Ninth Corps taking up positions to begin the attack.

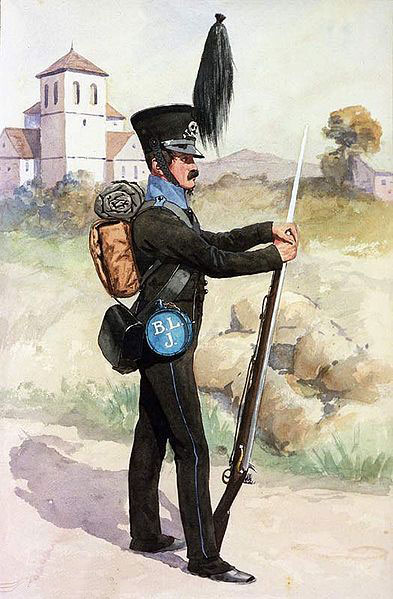

Chasseur Britannique: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd -5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Knötel

The British cavalry under Cotton, with Bull’s troop of Horse Artillery and the Light Division were sent to the right to support Houston’s Seventh Division and the First and Third Divisions were shuffled to their right.

The French divisions of Marchand and Mermet formed up behind Nave de Haver.

The first engagement of the day took place as the French cavalry advanced into the plain between Fuentes de Oñoro and Nave de Haver.

Lepic’s Horse Grenadiers of the Imperial Guard tried unsuccessfully to clear Houston’s skirmishers from the woods adjoining Poco Velho.

Fournier’s cavalry brigade was in the meantime advancing through Nave de Haver on Julian Sanchez guerrilla bands, which quickly withdrew.

This brigade next turned on two squadrons of the 14th Light Dragoons and drove them back to Poco Velho, where the French were repelled by a volley from a Seventh Division picquet concealed in the undergrowth.

Squadrons of the British 16th Light Dragoons and the KGL 1st Hussars charged Wathier’s Brigade, but were driven back on Poco Velho.

Incidents in which small groups of British cavalry attacked much larger French cavalry formations, usually without incurring many casualties, were a feature of the fighting in this part of the battlefield and helped keep the French at bay.

The French cavalry numbered some 3,000, while the British and Portuguese numbered around 1,500. The French cavalry failed to exploit the mismatch.

It would seem that a store of alcohol was discovered somewhere in this area of the battlefield and many of the French troopers are described as galloping around in no particular order, clearly drunk.

There was friction at the highest levels of command throughout the French army and particularly in the cavalry.

Montbrun requested Bessières to send him the six guns of the Imperial Guard that he had brought to the army. Bessières refused.

In addition, after their initial appearance on the battlefield, nothing was seen of the Horse Grenadiers of the Imperial Guard and it is said that Bessières refused to commit them again to the battle.

Following the French cavalry, Marchand’s Division emerged in column from behind Nave de Haver and marched north across the area of plain to Poco Velho, pushing the Seventh Division skirmishers back, before storming the village and driving its heavily outnumbered defenders of the 85th and the 2nd Caçadores up the hill.

These regiments were relieved by some British cavalry covering their right flank and the 95th Rifles advancing and bringing the French attack to a halt with their fire.

After something of a lull in the fighting, Montbrun ordered a general charge by the cavalry in the plain south of Poco Velho.

British 16th Light Dragoons attacking French Hussars: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd -5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

This charge cleared the British cavalry from the area.

Two guns of Bull’s horse artillery troop, commanded by Captain Norman Ramsay, found themselves caught up in the rush of French cavalrymen.

Ramsay and his gunners galloped through the French cavalry, defending themselves with their swords and reached safety in the British ranks behind Fuentes de Oñoro, assisted by troopers from the Royal Dragoons and the 14th Light Dragoons.

The main formations still remaining in the area around and beyond Poco Velho were the Light Division and Houston’s Seventh Division, now heavily threatened by the mass of French cavalry.

It was necessary for both these divisions to withdraw to the main British position at Fuentes de Oñoro, a distance of some 5 miles for Houston and 3 miles for the Light Division.

Craufurd formed the Light Division into squares to repel the French cavalry.

Escape of Captain Norman Ramsay with the 2 guns of Bull’s Troop at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by W. Heath

The Chasseurs Britanniques and Brunswick Oels Light Infantry of Houston’s Foreign Brigade repelled the French cavalry from an area of broken scrubland and positions behind a stone wall.

There was then a lull in the southern part of the battlefield.

The cavalry formations of Montbrun seem to have lost cohesion and Loison’s infantry divisions of Marchand and Mermet were involved in pursuing the British skirmishers in the woods instead of pressing an attack along the British line, at a time when the British Seventh and Light Divisions were isolated and vulnerable.

It would seem that internal strife amongst the French generals hampered their conduct of the battle, Bessières refusing to permit Montbrun to commit the Imperial Guard Cavalry Brigade of Lepic to the fighting.

Escape of Captain Norman Ramsay with the 2 guns of Bull’s Troop at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

Wellington ordered Houston to retreat in a north-westerly direction across the Turones stream, covered by the British cavalry and the Light Division.

The First and Third Divisions moved to the right of Fuentes de Oñoro, facing south and occupying a ridge running east-west, to block the French advance.

Houston fell back to the end of the right limb of the line with Julian Sanchez beyond his division.

Wellington’s line was in an L shape, his right resting on the deep ravine of the River Coa and Fuentes de Oñoro forming the angle.

Escape of Captain Norman Ramsay with the 2 guns of Bull’s Troop at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

It was now for the Light Division to undertake the daunting operation of retreating across the open plain from Poco Velho to Fuentes de Oñoro, a 3-mile march, subject to the hostile attention of Montbrun’s cavalry and guns.

Craufurd’s battalions set off across the plain, marching in close columns, ready to form square if attacked.

Marchand’s infantry took no part in the assault on Craufurd’s Division, but Montbrun unleashed all the cavalry available to him on the light infantrymen and rifles.

But the 3,000 French cavalry, while deeply threatening, were unable to press their attack on the Light Division, marching in good order across the plain, covered by skirmishing riflemen.

Completing the perilous march, the division came into position in the rear of the First Division.

Captain Home of the Third Guards attacked by a French Dragoon: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Harry Payne

Kincaid, who took part as an officer of the 95th Rifles, described the operation; ‘The execution of our movement presented a magnificent military spectacle, as the plain, between us and the right of the army, was by this time in the possession of the French cavalry, and, while we were retiring through it with the order and precision of a common field-day, they kept dancing around us, and every instant threatening a charge, without daring to execute it.’

The total casualties of the Light Division for the day were 67 among seven battalions.

The British cavalry passed behind the new line and dismounted after its supreme efforts against the overwhelming numbers of French horsemen.

Soon after this, a party of pursuing French hussars managed to overwhelm and capture a hundred Guards skirmishers deployed in front of Stopford’s Brigade.

British 1st Royal Dragoon: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd -5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Two squadrons of the Royal Dragoons and the 14th Light Dragoons charged to their rescue, releasing some of the Guardsmen and taking 25 prisoners among the French hussars.

This incident is described as the only solid success achieved by the French cavalry on that day.

For a time Montbrun’s cavalrymen lurked around in front of Wellington’s right wing, discharging their pistols and, in one incident, charging Thompson’s battery of guns, to be met with grape-shot and in another, attacking the 42nd, to be repelled by a volley.

After a time, the French cavalry drew off and their guns opened a long-range cannonade, doing little damage to the first British line, but inflicting casualties on the second line.

Wellington’s guns replied and their superior numbers enabled them to overpower the French guns.

A charge was made by the British 14th Light Dragoons and the Royal Dragoons against a French battery, but they were beaten off.

The French Sixth and Eighth Corps, throughout the day’s fighting, remained ready to launch attacks against the British Third and First Divisions, in Wellington’s centre.

No move was made, but their skirmishers advanced along the valley of the Turones, to be repelled by Captain O’Hare’s four companies of the 95th Rifles.

In Fuentes de Oñoro, Massena was cautious about renewing his attack on the strongly held village, following the French defeat two days before.

After around 3 hours of the French attack further south and its apparent progress, Massena ordered the village to be stormed for a second time.

Ferey’s Division again attacked Fuentes de Oñoro frontally, while three battalions of Claparède’s Division attacked the village on his left, accompanied by a heavy artillery bombardment.

The two Scottish regiments, the 71st Highland Light Infantry and the 79th Cameron Highlanders were driven back through the village, the 79th losing two companies taken prisoner.

The Scottish regiments rallied in the upper part of Fuentes de Oñoro and, reinforced by the 24th, went over to the attack, driving the French back to the river.

The French troops renewed the assault and drove the British regiments back to the top of the village, where they held on.

Escape of Captain Norman Ramsay with the 2 guns of Bull’s Troop at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Christopher Clark

Both sides reinforced their troops in Fuentes de Oñoro, Wellington sending in light companies from the First and Third Divisions and the 6th Caçadores and D’Erlon calling forward battalions from Conroux and Claperède’s Divisions.

The fresh French battalions, supported by a heavy artillery barrage, stormed through Fuentes de Oñoro, again pushing the British to the top of the village.

Colonel Cameron, commanding the 79th Cameron Highlanders, was killed.

British guns behind the village inflicted heavy casualties on the French Ninth Corps’ column, while General Pakenham brought forward the 88th Connaught Rangers, commanded by Colonel Wallace.

Under Officer of the French 9th Light Regiment: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd -5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

The 88th closed with the French 9th Light Infantry.

The 9th held their own for a time, but finally gave way and were driven back through the village by the 88th.

Another Highland battalion from Mackinnon’s Brigade, the 74th, joined the assault, while the 71st, 79th and 24th renewed the attack on the French in the village.

Terrible fighting took place throughout Fuentes de Oñoro.

It is reported that the 88th cornered a party of more than one hundred French grenadiers in a blind alley and bayonetted the entire force.

The British battalions drove the French columns back through Fuentes de Oñoro and across the Dos Casas Stream.

Following the second failed French assault on Fuentes de Oñoro, the French guns fired on the village, where the 88th and 74th fortified the lower streets, until the cannonade fell away and the battle ended.

The French attack had failed all along the British line.

On the 6th May 1811, the Light Division took over the defence of Fuentes de Oñoro from the 74th and 88th Regiments and spent the day fortifying the village, in case the French renewed their attack.

The day was otherwise spent in the removal of both sides’ casualties from the battlefield.

Casualties at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro:

In the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro, the British, Portuguese and Spanish had 1,522 men killed, wounded or captured.

The French had 2,192 men killed, wounded or captured.

Fortescue comments that the remarkable feature of the French casualties was the high number of officers, nearly triple the British officer casualties.

Fortescue takes this to indicate low morale in the non-commissioned ranks and an unwillingness to follow the officers into battle, leaving the officers unduly exposed.

This would not be surprising considering the ordeal the Army of Portugal had undergone in its invasion of Portugal and subsequent retreat and the obvious dissension among the senior French commanders.

Escape of Captain Norman Ramsay with the 2 guns of Bull’s Troop at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro on 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Robert Alexander Hillingford

British Regimental Casualties:

Officer British 52nd Light Infantry: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

1st Dragoons: 4 officers and 37

soldiers killed, wounded or captured

14th Light Dragoons: 5 officers and 32 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

16th Light Dragoons: 2 officers and 23 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

Royal Artillery: 3 officers and 28 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

Coldstream

Guards: 1 officer and 53 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

3rd Guards: 2 officers and 57 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

1st Foot: 9 soldiers wounded

5th Foot: 7 soldiers wounded

9th Foot: 4 soldiers wounded

24th Foot: 1 officer and 27 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

30th Foot: 4 soldiers wounded

42nd Foot: 1 officer and 32 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

45th Foot: 4 soldiers killed or wounded

50th Foot: 2 officers and 27 soldiers killed and wounded

51st Foot: 5 soldiers killed or wounded

60th Rifles: 4 officers and 24 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

71st Foot: 11 officers and 133 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

74th Foot: 4 officers and 66 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

79th Foot: 14 officers and 224 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

83rd Foot: 2 officers and 42 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

85th Foot: 4 officers and 49 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

88th Foot: 3 officers and 65 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

92nd Foot: 3 officers and 50 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

94th Foot: 7 soldiers killed or wounded

95th Rifles: 2 officers and 22 soldiers killed, wounded or captured

Follow-up to the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro:

Following the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro, Massena resolved to abandon Almeida. Three soldiers were sent with messages to the French commander in Almeida, General Brennier, ordering him to escape from the town with his garrison and join the main army.

One of the three messengers managed to reach the town and, on the night of 10th May 1811, Brennier led his garrison out of Almeida and with considerable skill managed to evade the British and Portuguese forces assembled to catch him and re-joined the Army of Portugal, although losing his baggage.

Massena withdrew his army across the River Agueda to Ciudad Rodrigo and Barba del Puerco.

‘In the Midst of Battle’ Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd -5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Sir John Everett Millais

Wellington was infuriated by the failure to intercept Brennier’s force and considered that Brennier’s escape from Almeida largely negated the success of the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro.

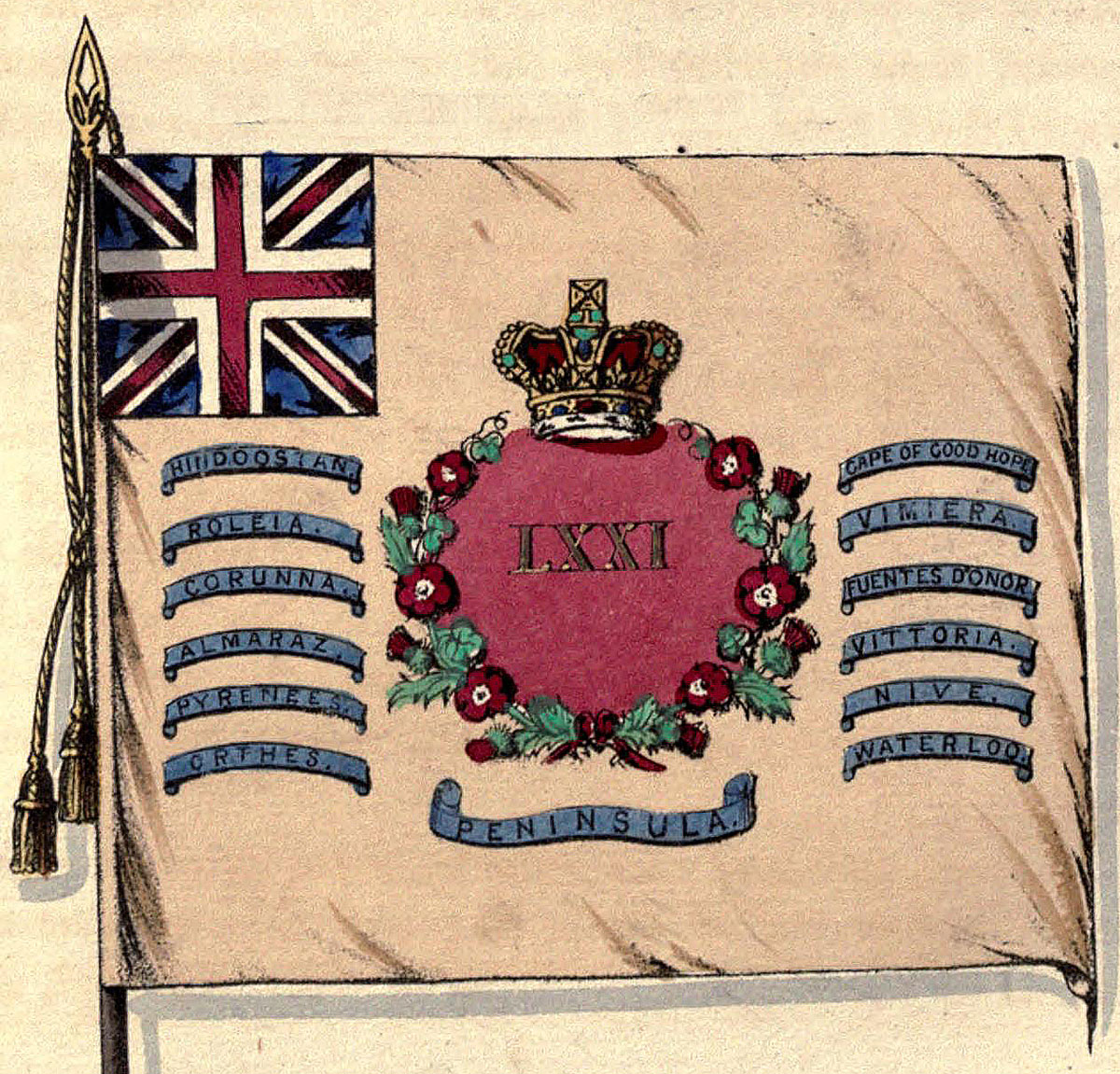

Regimental Colour of the 71st Highland Light Infantry showing the Battle Honour of the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

On 10th May 1811, General Foy arrived in Massena’s camp with letters from the Emperor Napoleon, relieving Massena of command of the Army of Portugal and appointing Marshal Marmont, the Duke of Ragusa, in his place.

After his considerable efforts on what was an impossible task, in invading Portugal, Massena was understandably enraged, although, on subsequent reflection, he may have been relieved to be removed from the nightmare of France’s involvement in the Peninsula.

Wellington did not claim the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro as a victory. He considered he had not handled the battle well, unnecessarily extending his line too far and putting the Seventh and Light Divisions in danger.

Military General Service Medal with clasp for ‘Fuentes d’Onor’: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

Medal and Battle Honour for the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro:

The Military General Service Medal 1848 was issued to all those serving in the British Army present at specified battles during the period 1793 to 1840, who were still alive in 1847 and applied for the medal. The medal was only issued to those entitled to one or more of the clasps. There were 21 clasps available for service in the Peninsular War.

The Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro, spelt as ‘Fuentes d’Onor’, was one of the clasps.

The battle honour ‘Fuentes de Oñoro’ , spelt as ‘Fuentes d’Onor’ was awarded to the following regiments: 1st Royal Dragoons, 14th and 16th Light Dragoons, 2nd and 3rd Foot Guards, 24th, 42nd, 43rd, 45th, 51st, 52nd, 60th, 71st, 74th, 92nd, 79th, 83rd, 85th, 88th Regiments and 95th Rifles.

Gold Medal awarded to Lieutenant Colonel Clement Archer 16th Light Dragoons for the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro

Army Gold Medal:

In 1810 a Gold Medal was issued to be awarded to officers of rank of major and above for meritorious service at certain battles in the Peninsular War, with clasps for additional battles. The ‘Large Gold Medal’ was awarded to generals, the ‘Small Gold Medal’ to majors and colonels, with the medal replaced by a cross where four clasps were earned. The Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro was one of the battles.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro:

- The episode during the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro of Captain Ramsey and the two guns of Bull’s Troop of Royal Horse Artillery bursting through the large force of French cavalry inspired an outpouring of paint by historical artists; Robert Hillingford, George Bryant Campion, William Barnes Wollen and many others. One striking representation is the picture ‘In the midst of Battle’ by Sir John Everett Millais. The details of the incident, the uniforms and guns are far from accurate but the subject matter comes through clearly.

- Bull’s Troop continues to serve in the British Army as I Parachute Headquarters Battery (Bull’s Troop), 7th Parachute Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery in 16 Air Assault Brigade.

- During the French assault on Fuentes de Oñoro on 3rd May 1811, one of Ferey’s battalions was Hanoverian in the French service. Their red tunics caused the British to take them to be friends and enabled them to form and fire unimpeded.

- Napier described the hazardous withdrawal of the Light Division from Poco Velho to behind Fuentes de Oñoro saying “there was not during the whole war a more perilous hour”.

Medal awarded to Major A. McIntosh of the 85th Light Infantry for gallantry at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War

- After the battle and before marchig away, the French paraded their British prisoners before Fuentes de Oñoro, mainly guardsmen and soldiers from the 79th Cameron Highlanders, Kincaid recorded in his book ‘Adventures in the Rifle Brigade’.

- The ‘Foreign Brigade’ in Houston’s Seventh Division comprised the Chasseurs Britanniques and the Brunswick Oels Light Infantry, along with the British 51st and 85th regiments. The Chasseurs Britanniques were formed from French Royalist émigré soldiers of the Prince of Conde’s army and fought in the British army until 1814, when the regiment was disbanded on Napoleon’s abdication. The Brunswick Oels corps, called ‘the Owls’ by their British comrades, was formed By the Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel to fight Napoleon. Both these regiments suffered from the difficulty of raising recruits during the course of the war in Spain, relying heavily on deserters from the French army and, in turn, suffering heavily from desertion.

- An incident occurred during the retreat of Houston’s Seventh Division, when a Portuguese battery commanded by a German officer mistakenly fired shrapnel over the Brunswick Oels Light Infantry, although no casualties were inflicted. The German officer was mortified to hear he had fired on his compatriots and then doubly mortified to hear that his gunners inflicted no casualties.

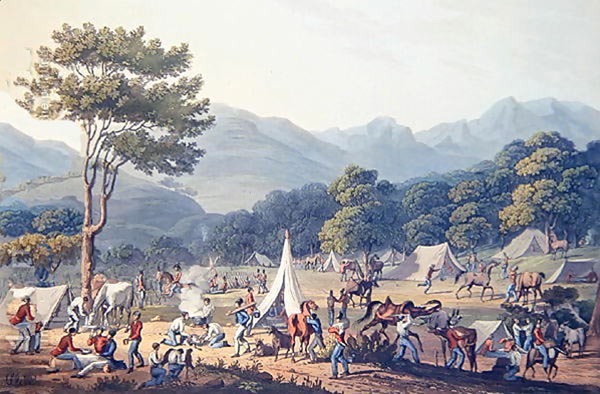

British troops bivouacking: Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by C. Turner

References for the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Sabugal

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Albuera

21. Podcast of the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro: Wellington’s hard-fought battle to prevent the French Army of Portugal under Marshal Massena relieving the fortress of Almeida on 3rd to 5th May 1811 in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts.