The successful rear-guard actions fought on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War, west and south of Ciudad Rodrigo, by Wellington’s troops against French cavalry

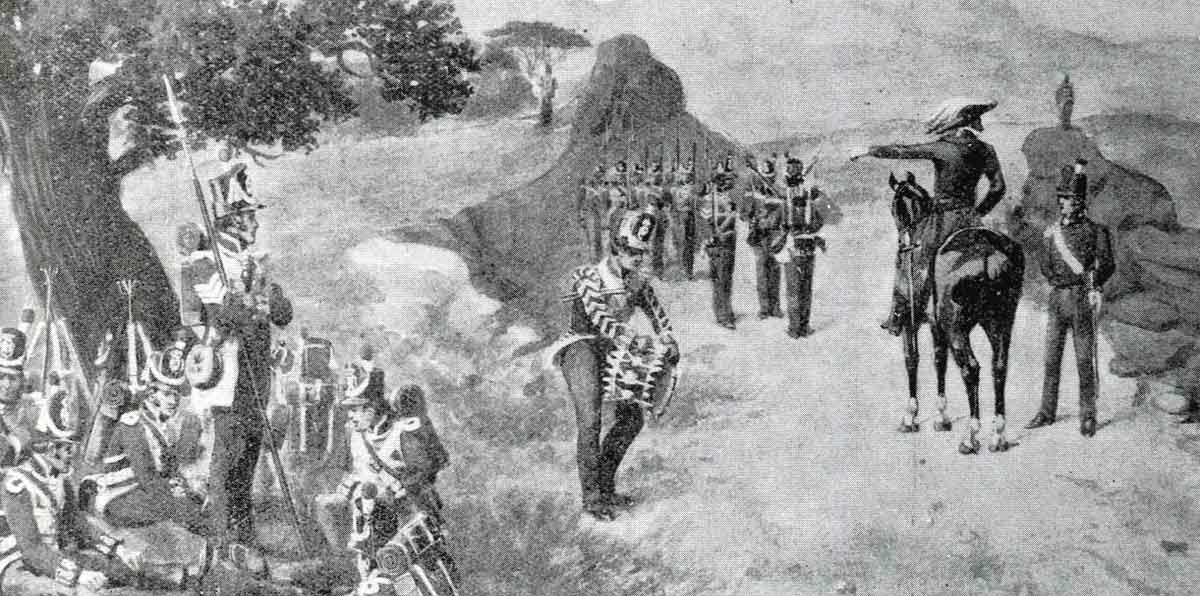

5th (Northumberland) Regiment of Foot attacking the French Cavalry at the Battle of El Bodon on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

24.  Podcast of the Battle of El Bodon: The successful rear-guard actions fought on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War by Wellington’s troops against French cavalry: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

Podcast of the Battle of El Bodon: The successful rear-guard actions fought on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War by Wellington’s troops against French cavalry: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of Usagre

The next battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of Arroyo Molinos

Battle: El Bodon

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of El Bodon: 25th September 1811

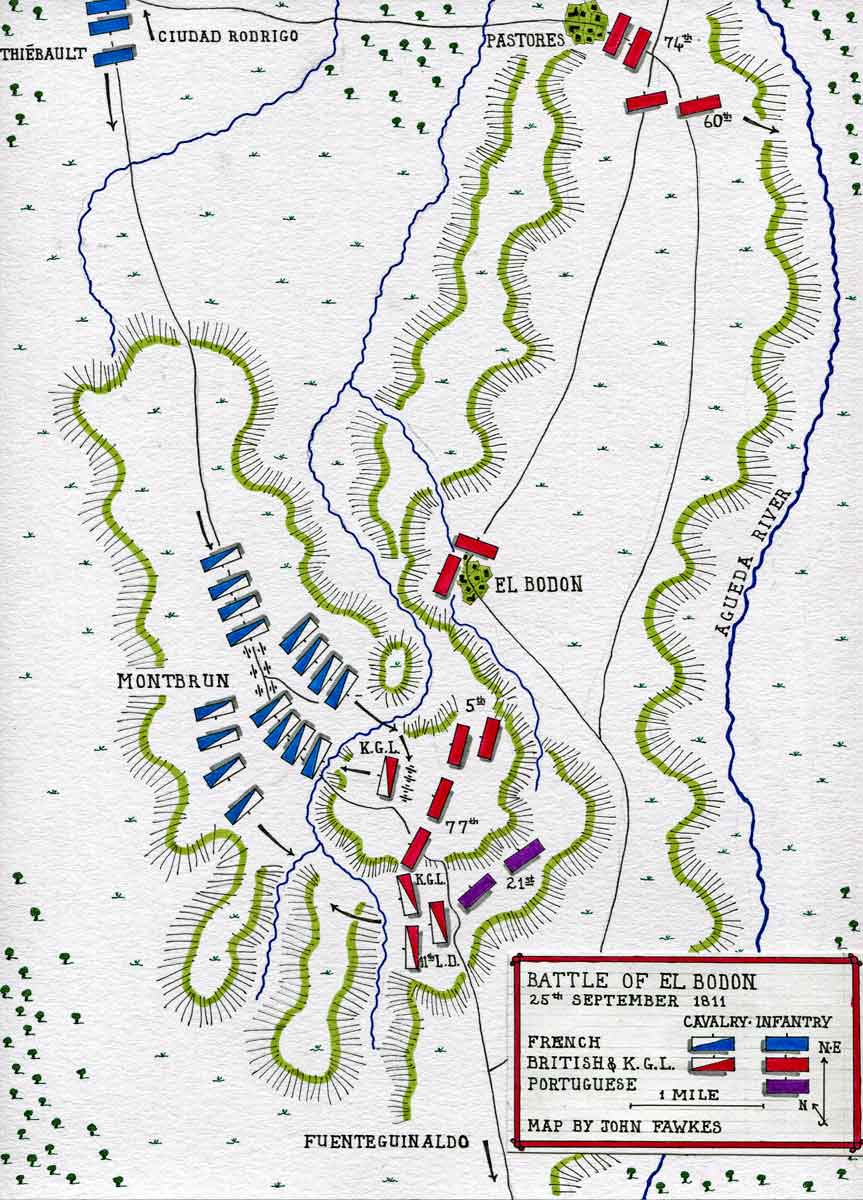

Place of the Battle of El Bodon: In Western Spain, immediately to the south of Ciudad Rodrigo, near the Portuguese border

General de Division Louis-Pierre de Montbrun, French commander at the Battle of El Bodon on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War

Combatants at the Battle of El Bodon: British and Portuguese troops against the French.

Commanders at the Battle of El Bodon: The overall commanders were Lieutenant General Viscount Wellington commanding the British and Portuguese army and Marshal Marmont commanding the French army.

The immediate commanders of the French troops were General Wathier and General Montbrun.

Size of the armies at the Battle of El Bodon: The numbers of troops immediately involved in the fighting were some 7,000 British and Portuguese troops against some 12,000 French troops.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of El Bodon:

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers and shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments, the 60th and 95th, wore dark green jackets and trousers.

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light cavalry wore light blue tunics with characteristic leather helmets covered by a bearskin crest.

The Portuguese army uniforms during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

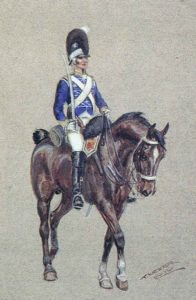

Drummer of the 1st Hussars, King’s German Legion: Battle of El Bodon on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue. Most infantry wore a shako headdress.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry. The horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket, that could be fired three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for around a hundred metres. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, fitting into the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, with a sword bayonet.

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who developed it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was not able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create a powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns, with the speed of French infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

Winner of the Battle of El Bodon:

The battle can be considered a success for Wellington. Attacked by Marmont’s cavalry, the British drove Wathier’s cavalry back to the River Azava and the British Third Division extricated itself from an awkward situation.

Background to the Battle of El Bodon:

In September 1811, Wellington’s army of British and Portuguese troops was deployed to the south and south-west of Ciudad Rodrigo on the Spanish border with Portugal.

The French garrison in Ciudad Rodrigo was under blockade from the British and Portuguese of Wellington’s army to the south and by Spanish troops to the north.

Although Marshal Marmont admitted in a despatch to Paris that the French were now on the defensive, on the receipt of a reinforcement of 2 divisions, Marmont felt bound to advance and re-supply the French garrison in Ciudad Rodrigo.

On 22nd September 1811, Marmont began his advance to Ciudad Rodrigo.

On 23rd September 1811, Marmont’s army combined with General Dorsenne’s army, giving a combined force of 58,000 men, of which some 5,000 were cavalry.

Wellington’s army numbered 46,000, of which some 28,000 were British.

Wellington’s army was hard hit by disease. 14,000 British troops were on the sick list, mainly from regiments newly landed from Walcheren and from the Guadiana.

Wellington could not prevent Marmont from entering Ciudad Rodrigo, but such a large French force was likely to reduce the supplies in Ciudad Rodrigo, rather than augment them.

Wellington’s army was dispersed between Fuenteguinaldo, to the south of Ciudad Rodrigo and Fuentes de Oñoro, to the west of the town, a spread of nearly 80 miles by road.

General Graham, Wellington’s second-in-command and commanding on the left, was uneasy at such a wide distribution.

Marmont decided to launch a strong cavalry probe of Wellington’s positions.

Dorsenne’s cavalry was to march towards Espeja, across the Azava River to the west of Ciudad Rodrigo.

Montbrun with his cavalry division would march south, towards Fuenteguinaldo.

Account of the Battle of El Bodon:

The two French cavalry forces began their forays at 8am on 25th September 1811.

The cavalry from Dorsenne’s army comprised the brigades of General Wathier and Lepic, commanded by Wathier. Among the French regiments were the Lancers of Berg.

Wathier left 6 squadrons at Carpio and advanced to the Azava River, the British falling back before him.

After crossing the Azava, Wathier left 4 squadrons at the river and advanced with the remaining 4 squadrons.

These 4 French squadrons were charged by 2 British squadrons, 1 from each of the 14th and 16th Light Dragoons and driven back.

The French cavalry rallied and resumed their advance but were subjected to a volley from the light companies of Hulse’s infantry brigade. They were then charged by 4 further squadrons, 2 from each of the 14th and the 16th Light Dragoons and pursued back to the river, ending Wathier’s incursion across the Azava.

South of Ciudad Rodrigo, Montbrun marched his 4 brigades of some 2,500 sabres straight down the road to Fuenteguinaldo, heading for the area occupied by the British Third Division.

General Craufurd commander of the Light Division at the Battle of El Bodon on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War

Wallace’s brigade of the Third Division was divided equally between Pastores and El Bodon, towns on the road between Fuenteguinaldo and Ciudad Rodrigo.

The road divided with one branch going through those two towns and the other taking the higher ground to the west.

The 5th (Northumberland) Regiment occupied the western road at this high point, with the remaining three battalions of Colville’s brigade (2/83rd, 2/88th and the ‘Old 94th) further back down the road.

Wellington took personal command of the situation.

Once it was clear that Montbrun was taking the higher, western road, Wellington ordered 2 Portuguese batteries, the 77th Regiment and 5 squadrons of Alten’s Brigade to support the 5th Regiment. In addition, the 21st Portuguese Regiment and a brigade from the Fourth Division in Fuenteguinaldo were ordered to support the 5th.

Marmont, cautious of Wellington’s ability to conceal his troops, assumed that the widely dispersed Third Division was fully supported and sent no infantry with Montbrun’s cavalry.

The British troops occupied a ridge over which the road ran through a rocky hollow.

Wellington deployed these troops with 2 squadrons of the 1st King’s German Legion Hussars in the centre, supported by the Portuguese guns. The British 5th (Northumberland) Regiment was placed on the right and another 1st Hussars squadron and 2 squadrons of the 11th Light Dragoons further back on the left.

1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion: Battle of El Bodon on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War

Montbrun’s cavalry advanced up the ridge in three columns, under heavy fire from the Portuguese guns.

As the central French column reached the crest of the ridge, it was charged by the 2 KGL Hussar squadrons and driven back to the foot of the incline.

On the left, the remaining KGL squadron and the 11th Light Dragoons drove Montbrun’s right column down from the ridge.

77th Regiment at the Battle of El Bodon on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War: pictures by Richard Simkin

On the British right, the French column broke into the Portuguese battery and captured 4 guns.

Before the French could remove the guns, the 5th (Northumberland) Regiment came forward in line, fired a volley into the French cavalry and attacked with the bayonet, driving them after their fellows down the ridge.

Montbrun sent forward more squadrons, but the whole force was held in check by repeated single squadron charges from the KGL Hussars and the 11th Light Dragoons.

The British 77th Regiment came up and assisted in holding off the French cavalry.

Montbrun persisted with his unsuccessful frontal attacks, until Thiébault’s infantry division appeared marching up the road from Ciudad Rodrigo in his support.

At this point, Montbrun sent a force of cavalry to work its way around the British right flank.

It was time for the British and Portuguese to abandon the position they had held so successfully.

Wellington formed the 5th and 77th Regiments into a single square and began the march back to Fuenteguinaldo, preceded by the 21st Regiment, which had come up in support, in another square.

On the eastern road, General Picton extracted his battalions from El Bodon and withdrew to join Colville’s brigade, fired on by the pursuing French artillery, but throughout in good order.

All these troops withdrew the 6 miles to Fuenteguinaldo.

Further British reinforcements from Fuenteguinaldo met the retreating column, headed by the 3rd Dragoon Guards. Montbrun abandoned his attack and fell back towards Ciudad Rodrigo.

With the arrival of Thiébault’s infantry, the two British regiments in Pastores, the 74th and the 60th, found themselves cut off from Fuenteguinaldo. Led by Colonel Trench of the 74th, they crossed to the far bank of the River Agueda, marched to Robleda and crossed back to the Fuenteguinaldo road, capturing a French patrol on the way.

Casualties at the Battle of El Bodon:

From Wathier’s incursion across the Azava River, the French lost 50 killed, wounded and captured, while the British casualties were no more than 12.

French casualties in the fighting in the area of El Bodon were probably around 200, while the British, German and Portuguese casualties were around 150.

Follow-up to the Battle of El Bodon:

Wellington was by no means in the clear once his troops were withdrawn.

Marmont ordered his infantry to march up to threaten the British Third Division positions in Fuenteguinaldo.

Wellington gave instructions to the divisions on the left flank to close in and withdraw.

He directed the Light Division to march immediately to Fuenteguinaldo, with the aim of falling back to a safer position.

General Craufurd, commanding the Light Division, for his own reasons, instead of obeying his instructions to march straight to Fuenteguinaldo, halted for the night, arriving at Fuenteguinaldo the next afternoon.

Grenadier of the 5th (Northumberland) Regiment: Battle of El Bodon on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Grenadier Officer of the 5th (Northumberland) Regiment: Battle of El Bodon on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Wellington was compelled to wait for Craufurd until the following afternoon, under threat of attack from the build-up of Marmont’s infantry, before beginning his retreat to a safer position.

In fact, Marmont had no intention of attacking Wellington and, on 26th September 1811, the French withdrew to Ciudad Rodrigo.

On 1st October 1811, after resupplying the French garrison in Ciudad Rodrigo and destroying quantities of gabions and fascines Wellington’s soldiers had prepared for the intended siege works, Marmont and Dorsenne parted company and left Ciudad Rodrigo, Marmont heading north.

The French garrison was left to deal with the threat from Wellington’s army as best it could.

Medal issued by the British 77th Regiment to commemorate the Battle of El Bodon on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War

Medal and Battle Honour:

The Battle of El Bodon is not a clasp on the Military General Service Medal 1848 and is not a British Regimental Battle Honour.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of El Bodon:

- The 5th (Northumberland) Regiment of Foot was led into action at the Battle of El Bodon by Major Ridge. Napier described Ridge as a ‘daring man’. Fortescue refers to the regiment as ‘the Fifth Fusiliers’. In fact, the 5th was not made a Fusilier regiment until 1836. At this time the only Fusilier regiments were the Royal (7th), Royal Scots (21st) and Royal Welch Fusiliers (23rd).

- Fortescue commented of the Battle of El Bodon: ‘The whole affair of course was a repetition on a smaller scale of the retreat of the Light Brigade from Fuentes de Oñoro; and in both actions the same features are conspicuous, namely the powerlessness of the French cavalry against British squares, and the ease with which it could be thrust back by a mere handful of British or German horse.’

References for the Battle of El Bodon:

History of the Peninsula War by Sir William Napier Volume 1

History of the British Army by John Fortescue Volume 8

The previous battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of Usagre

The next battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of Arroyo Molinos

24.  Podcast of the Battle of El Bodon: The successful rear-guard actions fought on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War by Wellington’s troops against French cavalry: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

Podcast of the Battle of El Bodon: The successful rear-guard actions fought on 25th September 1811 in the Peninsular War by Wellington’s troops against French cavalry: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts