The destruction of Girard’s French Division by General Rowland Hill on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War

25. Podcast of the Battle of Arroyo Molinos: the destruction of Girard’s French Division by General Rowland Hill on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

25. Podcast of the Battle of Arroyo Molinos: the destruction of Girard’s French Division by General Rowland Hill on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of El Bodon

The next battle in the Peninsular War is the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo

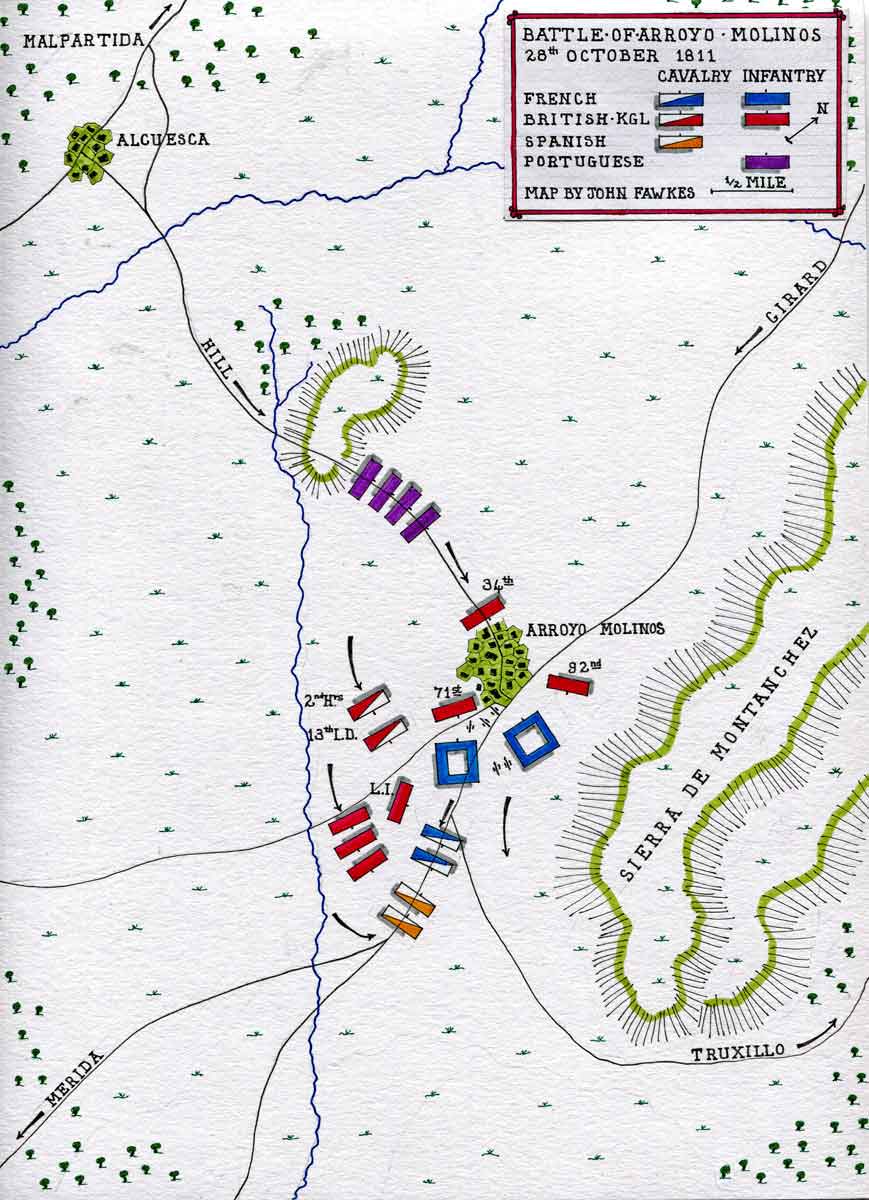

Battle: Arroyo Molinos

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of Arroyo Molinos: 28th October 1811

Place of the Battle of Arroyo Molinos: In South-Western Spain, to the north-east of Badajoz, near the Portuguese border.

Combatants at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos: British, Spanish and Portuguese troops against the French.

Rowland Hill, British commander at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War

Commanders at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos: The commander of the British and Portuguese force was General Rowland Hill.

The Spanish contingent was commanded by General Morillo.

The commander of the French force was General de Division Jean-Baptiste Girard.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos:

General Hill’s British and Portuguese contingent numbered around 8,000 men.

The Spanish contributed around 2,000 men to Hill’s force.

General Girard’s division numbered around 6,000 men.

General Girard, French commander at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos:

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers and shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments, the 60th and 95th, wore dark green jackets and trousers.

Highland troops wore the kilt and feather bonnets.

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light cavalry wore light blue tunics with characteristic leather helmets covered by a bearskin crest.

The Portuguese army uniforms during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue. Most infantry wore a shako headdress.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry. The horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket, that could be fired three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for around a hundred metres. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, fitting into the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, with a sword bayonet.

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who developed it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was not able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create a powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns, with the speed of French infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

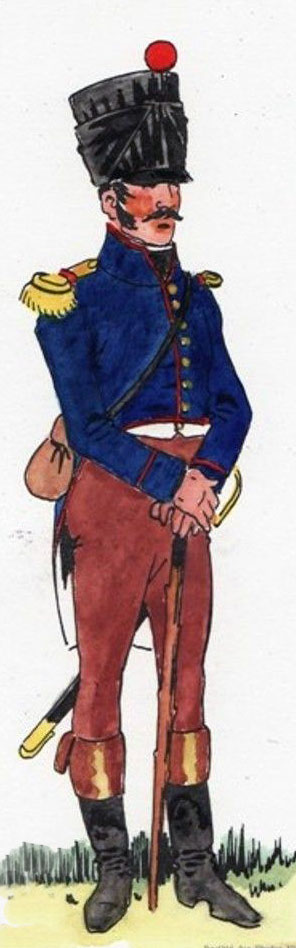

British 13th Light Dragoon: Battle of Arroyo Molinos on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

Winner of the Battle of Arroyo Molinos:

General Girard’s division was effectively destroyed, with the exception of the brigade led by General Rémond, which left Arroyo Molinos before the battle and evaded destruction.

British and Portuguese Order of Battle at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos:

Howard’s Brigade: 1st/50th, 1st/71st, 1st/92nd

Wilson’s Brigade: 1st/28th, 1st/34th, 1st/39th,

Long’s Cavalry Brigade: 9th and 13th Light Dragoons and 2nd Hussars K.G.L.

Portuguese Regiments: 4th, 6th, 10th, 18th Regiments (2 battalions each) and 6th Caçadores (1 battalion)

Background to the Battle of Arroyo Molinos: in October 1811, Marshal Marmont’s Army of Portugal returned to the north-west of Spain, leaving Wellington’s main army in positions along the Portuguese border, west of Ciudad Rodrigo.

Marshal Soult, with his Army of the South, was busy with his schemes for self-aggrandisement in Andalusia.

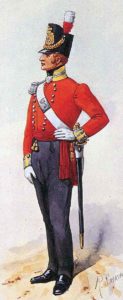

Officer of the 34th Regiment of Foot: Battle of Arroyo Molinos on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Simkin

General Rowland Hill, with around 16,000 men, was based at Portalegre, on the Portuguese-Spanish border to the west of Badajoz on the Guadiana River. Hill’s duty was to observe and cover D’Erlon’s French Fifth Corps in Estremadura.

The remnants of the Spanish army of Castaños, some 4,000 men, lay at Valencia de Alcantara to Hill’s north.

The obligation on D’Erlon was to maintain communications between Marmont in the north and Soult in the south.

To fulfil this obligation, D’Erlon dispatched General Girard with his division to occupy the gap between the River Tagus and the River Guadiana.

General Girard was left exposed to the north of the Guadiana River, with Hill and Castaños to his west.

In October 1811, Girard marched north from Merida on the Guadiana River, to drive back the Spanish, who had advanced as far as Caçeres, to preserve the area from which he could gather supplies.

Once it became clear that Soult did not intend any incursion into Estremadura to re-supply the French garrison in Badajoz, Hill sought Wellington’s leave to attack Girard, which Wellington gave.

Castaños agreed to provide a Spanish force for the enterprise.

Hill assembled his force and marched east, on 22nd October 1811, from Portalegre.

Hill’s route was through Alagrete, over the Serra de São Mamede, to La Cordosera.

French Light Infantryman: Battle of Arroyo Molinos on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by PA Leroux

The weather was bad, raining with heavy winds and the roads atrocious.

On 23rd October 1811, Hill’s army reached Alburquerque.

Receiving information from the Spanish that Girard was falling back to the east, Hill marched on to Aliseda, arriving on 25th October 1811.

That night Hill’s force marched on, in pouring rain, to Malpartida, a village 6 miles short of Caçeres, to discover that Girard had left that town the previous afternoon.

Hill halted to await firm information as to Girard’s route.

At 3am on 27th October 1811, Hill was informed that Girard had taken the road south to Torremocha.

Hill followed Girard, taking the road to the west of and parallel to the road through Torremocha.

On his way south, Hill received information from the local Spanish that Girard had turned east to Arroyo Molinos. Hill was also told that a French rear-guard had been left at Albalat, on the road from Torremocha. This indicated that Girard was unaware of Hill’s true route, if he realised at all that he was being followed.

———————————-

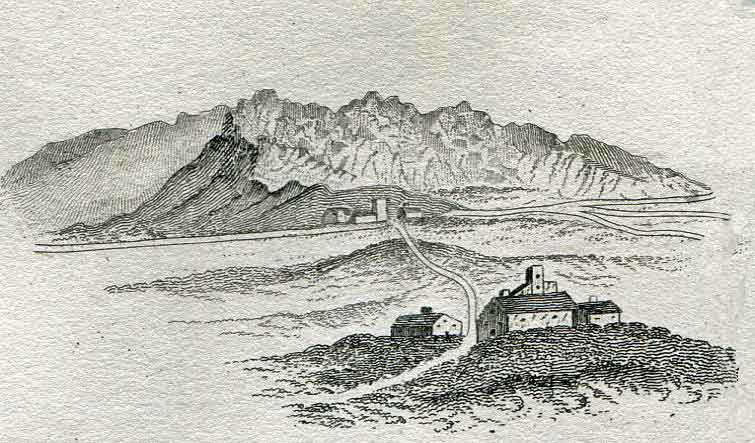

Arroyo Molinos with Alcuescar in the foreground: Battle of Arroyo Molinos on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War: drawn by General Napier

Hill hurried his men on, reaching the village of Alcuescar, 4 miles short of Arroyo Molinos, where Girard’s French force was passing the night. Hill had marched some 28 miles from Malpartida.

The 71st Highlanders occupied Alcuescar and positioned sentries to prevent anyone leaving on the road to Arroyo Molinos and warning the French of their danger.

The main column encamped short of Alcuescar. No fires were permitted. During the night a storm blew down the tents and soaked the soldiers.

Account of the Battle of Arroyo Molinos:

At 2am on 28th October 1811, the British and Portuguese regiments were aroused and fell in for the attack on Girard’s division.

The town of Arroyo Molinos lies on the edge of a high plain, bounded on its eastern side by the end of a mountain ridge, the Sierra de Montanchez.

The town is the centre of a web of five roads, along the western of which, Hill’s force was advancing to the attack.

At 6am on 28th October 1811, Hill’s troops arrived within a mile of Arroyo Molinos and halted.

Hill formed his force into three columns: the first, comprising Howard’s brigade and Morillo’s Spanish infantry, commanded by Colonel Stewart of the 50th Regiment, was to advance straight into Arroyo Molinos: the second, comprising Wilson’s brigade, 3 Portuguese battalions and 3 guns, commanded by General Howard, was to march around the southern side of Arroyo Molinos and cut the two roads to the south: the third, comprising the cavalry under General Sir William Erskine, was to be held as a reserve.

British 13th Light Dragoons attacking the French guns at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War

The final approach march of Hill’s force was covered by a thick fog.

On 28th October 1811, the French in Arroyo Molinos were intending to make an early start in their march to the south and the brigade of Rémond, with a regiment of cavalry, was on its way to Merida before dawn and beyond recall at the time of the battle.

The main part of Girard’s division was forming up outside the town, with the baggage and rear-guard still in the town, when Stewart’s column attacked.

The 71st and 92nd Highland Regiments charged down the main street, driving the French troops before them at the point of the bayonet. Dozens of French soldiers were taken prisoner.

Girard hurried his 6 battalions out of the town and formed them into two squares to receive the British attack. The French left was between the two southern roads, covered by cavalry.

The 71st lined the outer perimeter of the town and opened fire on the French as they endeavoured to take up their positions, while the 92nd formed up on the French flank, intending to charge.

The 3 guns of Howard’s column came up and opened fire with grape shot, cutting down swathes of French troops.

The Spanish cavalry occupied the road to Merida, Girard’s intended route, cutting off his escape to the south.

Girard instructed his 2 cavalry regiments, the 27th Chasseurs à Cheval and the 10th Hussars, to clear the Merida road at whatever cost.

2nd Hussars, King’s German Legion: Battle of Arroyo Molinos on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Knötel

General Long came up with the 2nd KGL Hussars and the British 9th Light Dragoons and joined the Spanish cavalry in their fight with the 2 French cavalry regiments.

In the desperate struggle, the 2 French regiments were overwhelmed and over 200 French troopers taken prisoner, together with the French chef de brigade, General Bron, who is said to have shot 2 troopers of the 9th, before surrendering to a light dragoon trumpeter.

With his escape route blocked, Girard led his division to the Truxillo road to the east, headed by the French artillery at the trot.

Howard’s column was marching around the town to cut off the Truxillo road, at a point where it rounds a promontory of the Sierra de Montanchez.

The light companies of Wilson’s brigade made to cut across to the road to intercept the French, but Hill ordered them to continue on to the promontory, leaving the pursuit to the cavalry.

Hill galloped on to the promontory, arriving with only his aide-de-camp, as the French column came up the road.

Simultaneously with the French, Hill was joined by the light companies, commanded by Lieutenant Blakeney of the 28th Regiment.

Hill directed Blakeney to lead his 200 men in a charge with the bayonet against the French column, which numbered some 1,500 men.

Girard, now wounded, ordered his men to disperse and, leaving his horse, led the escape on foot of some 200 of his men up the mountainside.

The remainder of the French column was now surrounded by the converging British and Portuguese troops and laid down their arms.

Blakeney’s light company men pursued Girard and his escaping troops over the mountain and down the far side, where the French found Hill’s cavalry waiting for them.

Girard’s men turned back up the mountainside and headed off, pursued by the Spanish troops over a distance of some 30 miles. Most of the French party were killed or captured.

Girard and his brigadier, Dombrowski, managed to escape.

With the battle finished, Hill sent Long’s cavalry and the unengaged Portuguese regiments in pursuit of Rémond. But, warned of the attack at Arroyo Molinos, by fleeing dragoons, Rémond hurried on without halt and escaped.

Hill marched, with his French prisoners, south to Merida and then, on Wellington’s orders, returned to his base of operations at Portalegre on 4th November 1811.

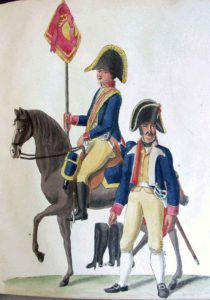

Standard Bearer and Trooper of Spanish Cavalry: Battle of Arroyo Molinos on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Suhl

Casualties at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos:

The British, Spanish and Portuguese force commanded by General Hill at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos suffered under 100 casualties.

The only British regimental casualties recorded are those of the 92nd, which suffered 4 officers wounded, 3 soldiers killed and 7 wounded.

From a force of 2,600 men, the French suffered 1,300 taken prisoner and 710 killed. Some 500 French soldiers escaped.

Among the captured French officers were General Bron, Colonel the Prince d’Arenberg, commander of the 27th Chasseurs à Cheval and a further 35 officers from the rank of lieutenant-colonel down.

The French troops who escaped abandoned their artillery, muskets, baggage and supplies.

However no Regimental Eagles were taken by the British.

Officer of D’Arenberg’s 27th Chasseurs à Cheval: Battle of Arroyo Molinos on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War: picture by Knötel

Follow-up to the Battle of Arroyo Molinos:

On receiving the report of the battle, Wellington said that Hill had performed his business handsomely. Hill received the acclamations of the whole army in the Peninsular.

The Emperor Napoleon was furious at the conclusive defeat of his troops at Arroyo Molinos and deprived Girard of his command. He also criticised Marshal Soult for leaving so small a force vulnerable to attack.

This short campaign concluded operations in the west of Spain for 1811.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Arroyo Molinos:

- Napier states that every Spanish resident of Arroyo Molinos knew of the impending attack, but no one warned the French. In contrast, Hill was given full information of Girard’s movements by the Spanish. This was a microcosm of the difficulties faced by the French throughout the Peninsular War. The inhabitants of the countryside told the French nothing, but told the British everything.

- On the other hand, the Prince D’Arenberg recorded that a Spanish couple came to him the night before the battle and warned him of the impending attack. Girard was informed but rejected the reports, saying that the British, Portuguese and Spanish were 8 leagues away.

- The Prince D’Arenberg, a Belgian nobleman, raised and commanded a regiment of Chasseurs à Cheval to serve in the French Army. Initially named the ‘Chasseurs D’Arenberg’ the regiment was incorporated into the French line as the 27th Chasseurs à Cheval. D’Arenberg was accompanied on campaign by a number of servants including a valet and a coachman. Captured at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos after the death of his horse, D’Arenberg was escorted to Lisbon by a party from the 34th Regiment and kept in captivity in England until Napoleon’s abdication in 1814. In order to sample Lisbon’s night life incognito, D’Arenberg was compelled to shave off his distinctive ‘Hussar Moustaches’.

- The only British regiment to be given the battle honour for the Battle of Arroyo Molinos was the 34th Regiment of Foot. This caused considerable resentment among the other regiments to have taken part in the battle, several of which considered their part to have been more significant than that of the 34th. A number of applications have been made, over the years, for the battle honour to be awarded to these regiments, particularly the two Highland regiments, the 71st and the 92nd. All applications to the authorities have been rebuffed. The 34th, later the Border Regiment, then the King’s Own Royal Border Regiment and now the Duke of Lancaster’s, is the only regiment to carry the battle honour ‘Arroyo dos Molinos’.

- The British 34th captured six drums of the French 34th of the Line and the drum major’s mace at the Battle of Arroyo Molinos.

- As Fortescue points out, the British Army has the name of the town wrong. It is called ‘Arroyo Molinos de Montanchez’ or ‘Mill stream of Montanchez’, not ‘Arroyo dos Molinos’ as shown on the 34th’s colours and cap badge.

- No clasp was issued for the Military General Service medal 1793-1814 for the Battle of Arroyo Molinos.

- For his conduct of the Battle of Arroyo Molinos, General Hill became Sir Rowland Hill with a Knighthood of the Bath. Pleasure at this honour was expressed by all those who knew the general. An officer of the King’s German Legion stated: ‘The man seems to be beloved by all.’

- General Girard was restored to the Emperor Napoleon’s favour and continued to serve in the French Army with distinction. Commanding the 7th Division at the Battle of Ligny on 16th June 1815, Girard was mortally wounded defending the important village of Saint-Amand-la-Haye against the Prussians. As one of the Emperor Napoleon’s last official acts, Girard was made ‘Duc de Ligny’, before he died.

References for the Battle of Arroyo Molinos:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle in the Peninsular War is the Battle of El Bodon

The next battle in the Peninsular War is the Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo

25. Podcast of the Battle of Arroyo Molinos: the spectacular destruction of Girard’s French Division by General Rowland Hill on 28th October 1811 in the Peninsular War: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts