Wellington’s unsuccessful assault on the Spanish City of Burgos, between 19th September and 25th October 1812, during the Peninsular War, following the Battle of Salamanca

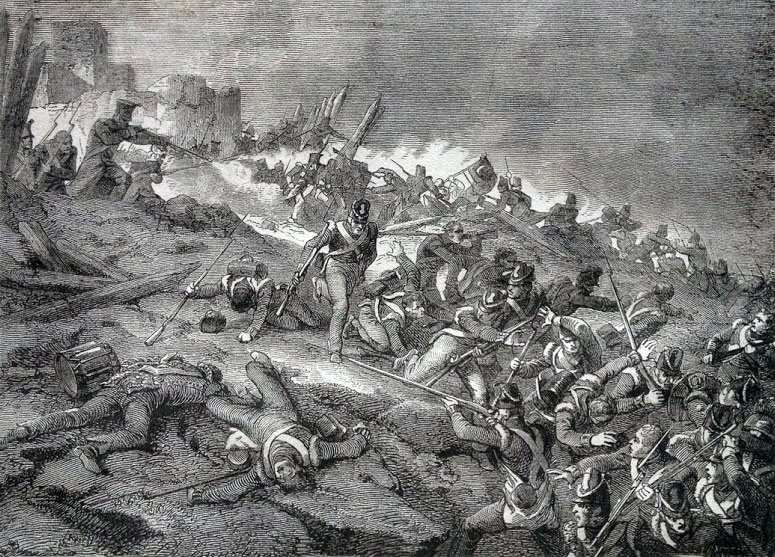

Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Heim

Podcast on the Attack on Burgos between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: Wellington’s unsuccessful assault on the Spanish City following the Battle of Salamanca: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

Podcast on the Attack on Burgos between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: Wellington’s unsuccessful assault on the Spanish City following the Battle of Salamanca: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Majadahonda

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Retreat from Burgos

To the Peninsular War index

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Attack on Burgos: 19th September to 25th October 1812

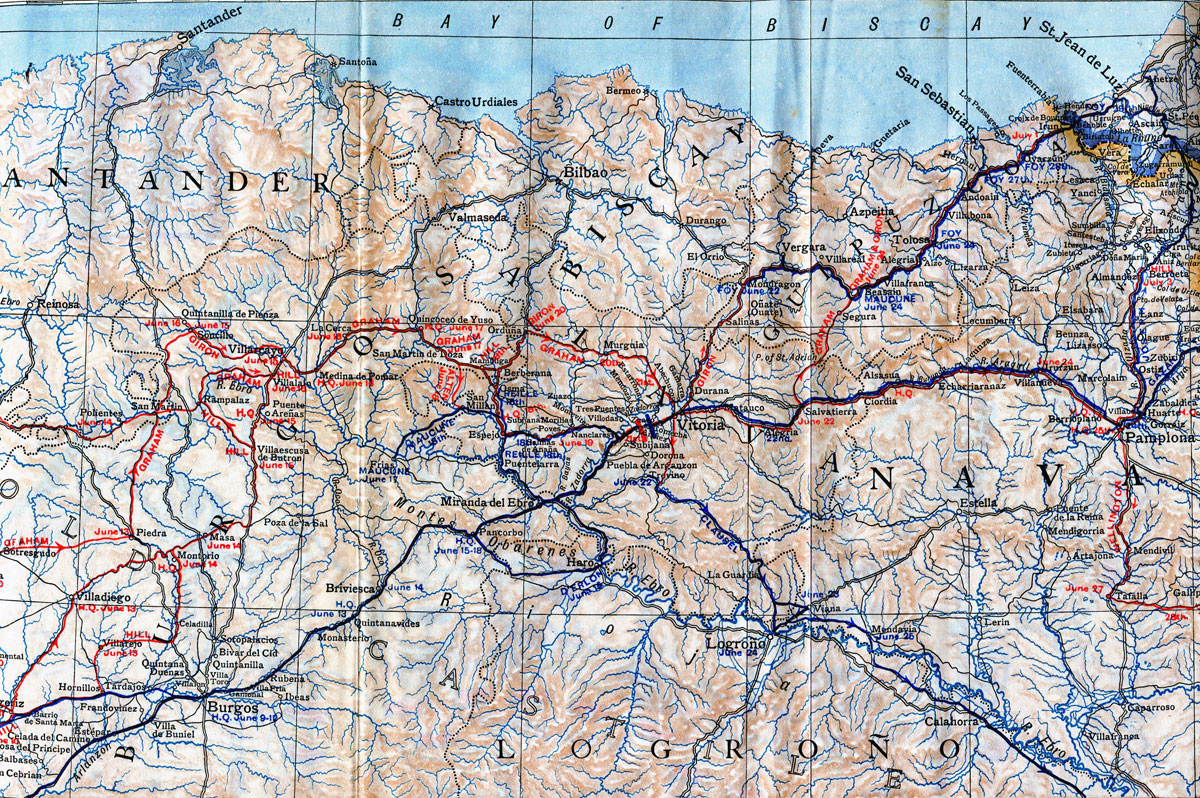

Place of the Attack on Burgos: in Spain, north-west of Madrid.

Combatants at the Attack on Burgos: British, Portuguese and Spanish against the French

General Dubreton, French garrison commander during the Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War

Commanders at the Attack on Burgos: Lieutenant General the Earl of Wellington against General Dubreton, the commander of the French garrison in Burgos Castle

Size of the armies at the Attack on Burgos: 35,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish troops against a garrison of 2,000 French troops.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Attack on Burgos:

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers, and stovepipe shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments wore dark green jackets and trousers.

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

Highland regiments wore the kilt with red tunics and black ostrich feather caps.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and black fore and aft cocked hats. The change in uniform brought in during 1812 saw the British heavy cavalry adopt ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

The British light dragoons wore light blue uniform coats and a leather helmet with a fur crest running front to back.

From 1812, the British light cavalry increasingly adopted hussar uniforms, with some regiments changing their title from ‘light dragoons’ to ‘hussars’.

The King’s German Legion (KGL) was formed largely from the old disbanded Hanoverian army. The KGL owed its allegiance to King George III of Great Britain, as the Elector of Hanover, and fought with the British army. The KGL comprised both cavalry and infantry regiments. KGL uniforms followed the British.

Private of the Coldstream Guards: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War

The Portuguese army uniforms increasingly during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

The Spanish army essentially was without uniforms, existing as it did in a country dominated by the French. Where formal uniforms could be obtained, they were white.

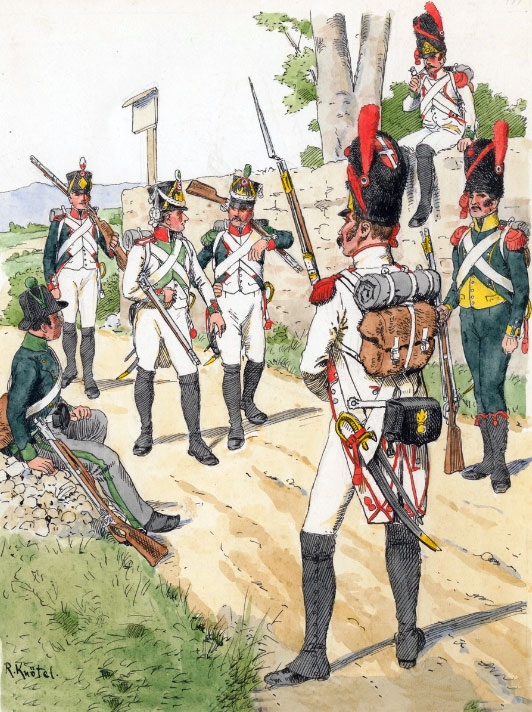

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe, and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry, the horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket. The musket could be fired at three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for a hundred metres or so. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, which fitted the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, and a sword bayonet.

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who invented it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was not able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create his powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns with the speed of the French columns of infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

Winner of the Attack on Burgos: Wellington’s attack was decisively repelled by the French garrison.

Background to the Attack on Burgos:

On 12th August 1812, Wellington’s army entered the Spanish capital, Madrid, following its victory over Marmont’s French Army of Portugal at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812.

Wellington’s army received an enthusiastic reception from the inhabitants, while Joseph Buonaparte, the Emperor Napoleon’s brother and King of Spain, escaped east towards Valencia with his French army and those residents of Madrid committed to the French.

A French garrison of 2,000 men remained in Madrid, in and around the Retiro Palace.

The next day, under threat of a heavy bombardment, the Retiro garrison surrendered to Wellington.

Other French garrisons between Madrid and the Portuguese border were in danger of capture.

Burgos Castle: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War

General Clausel, commanding the French Army of Portugal in place of Marmont, wounded at Salamanca, seized the opportunity of Wellington’s diversion to Madrid to march south and rescue such French garrisons as he could reach.

Clausel entered Valladolid on 16th August 1812 and sent General Foy west to rescue the outlying French garrisons. Foy returned to Valladolid on 29th August 1812, with the garrisons of Toro, Beneventa and Zamora; the French in Astorga having surrendered 36 hours before Foy reached them.

Wellington began his move against Clausel’s Army of Portugal on 16th August 1812, with the initial concentration of most of his army at the Escorial Royal Palace, 20 miles to the north-west of Madrid.

On the same day, Clausel marched north to positions around Burgos.

Wellington advanced on Burgos, preparing to attack Clausel’s army, but on 17th September 1812, Clausel marched through Burgos and continued north, leaving a French force in the castle.

The French garrison left to hold Burgos Castle comprised 2,000 men under the command of General Dubreton.

Assault on Burgos Castle:

Wellington took the view that the City of Burgos, once captured, would secure his position in western central Spain, standing as it does at the junctions of the roads from the north and from France in the north-east, with the roads leading south to Madrid and south-west to the Portuguese border. At Burgos, these roads cross the River Arlanson.

The difficulty Wellington faced was that, not expecting to win a decisive battle at Salamanca and expecting to be forced to retreat, he had ordered his heavy artillery back to Ciudad Rodrigo. The British army was without the heavy artillery required for an attack on a fortified citadel such as Burgos Castle.

French infantry: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Knotel

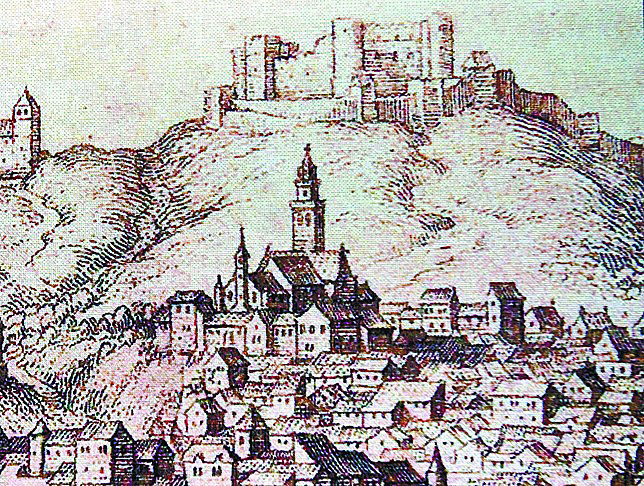

Fortescue describes Burgos in these terms: ‘The country about the upper waters of the Arlanson consists of chalk downs naturally scarped; and it is upon a chalk hill, rising high and abruptly from the north side of the river that the Castle of Burgos stands, with the town spread out at its foot.’

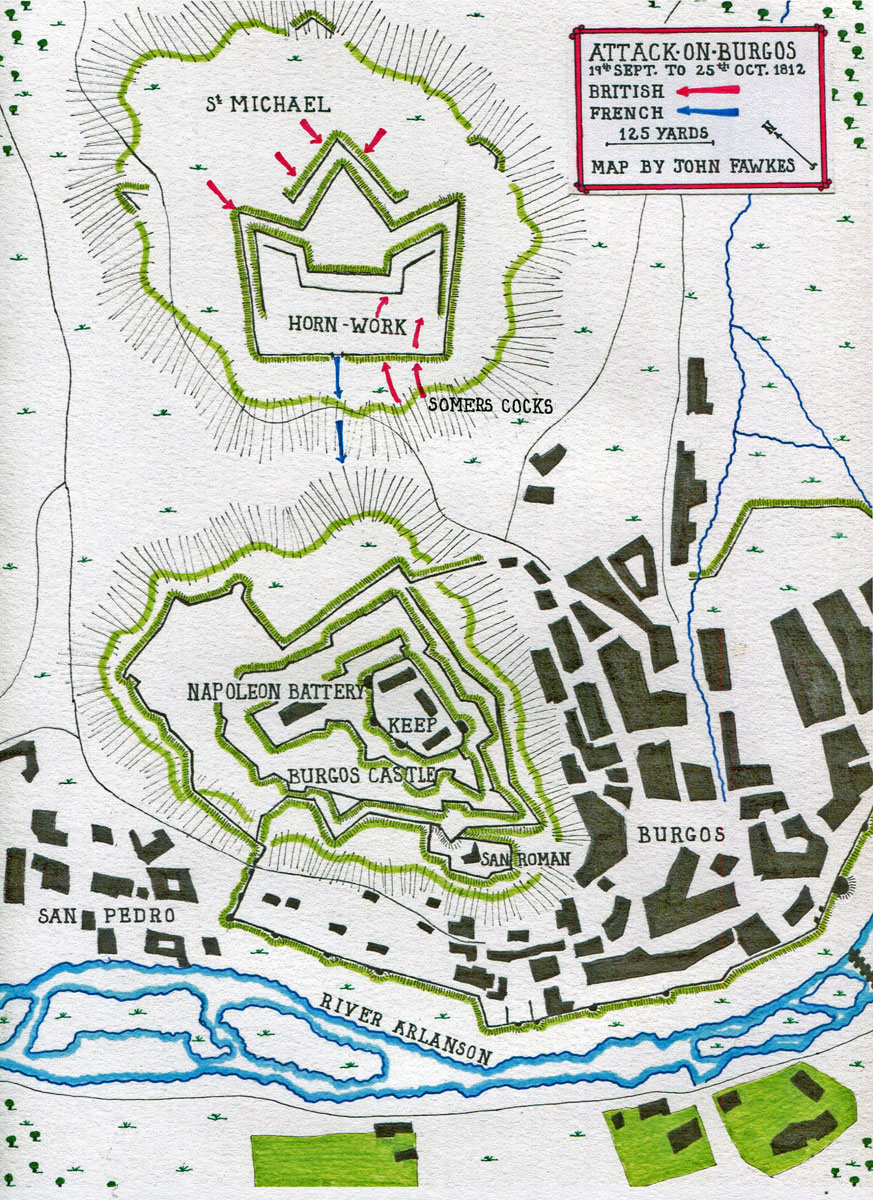

Burgos Castle was defended by three lines of fortification. The first was the old medieval wall, strengthened with an earth parapet. The second was a palisaded field-work. The third fortification was a revetted palisade protected by a ditch.

On the top of the Castle hill was a church and the ancient keep, now a retrenchment with a newly built casemated work called the Napoleon Battery.

300 yards to the north-east of Burgos Castle lies a hill called St Michael, which rises 150 feet higher than the castle.

When in Spain, Napoleon ordered the building of a horn-work on St Michael, similar in size to the Castle and rising to 150 feet above it. Much work remained to be completed, but it was a strong work with the rear closed by a palisade.

The guns in the Napoleon Battery dominated the interior of the horn-work on St Michael.

19th September 1812:

On 19th September 1812, Burgos Castle was surrounded by the British First, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Infantry Divisions with 2 Brigades of Portuguese infantry.

The Sixth Division occupied the south bank of the Arlanson River, while the remaining divisions crossed the river and occupied the St Michael heights in front of the horn-work and drove in the outlying French posts.

The remainder of Wellington’s army took up position 9 miles to the north-east of Burgos, at Monasterio de Rodilla on the road to France.

Fortescue states that taking Burgos Castle would have been little of a problem to an army with a full siege-team and experienced in such operations.

Unfortunately for Wellington, due to the threat from Marmont’s Army of Portugal before the Battle of Salamanca, he had sent his heavy guns back to Ciudad Rodrigo, to avoid their loss in the event of a sudden withdrawal.

For the attack on Burgos Castle, Wellington could deploy only three 18 pounder cannon and five 24 pounder howitzers and his supplies of gunpowder were inadequate for the expenditure required in a siege operation.

Against this armament, the French garrison deployed 9 heavy guns, 11 field guns and 6 mortars.

In addition, the ordnance of the Army of Portugal’s reserve artillery was stored in Burgos Castle, providing replacement pieces for any damaged or destroyed.

The initial operation, the storming of the horn-work on St Michael, took place on the first night.

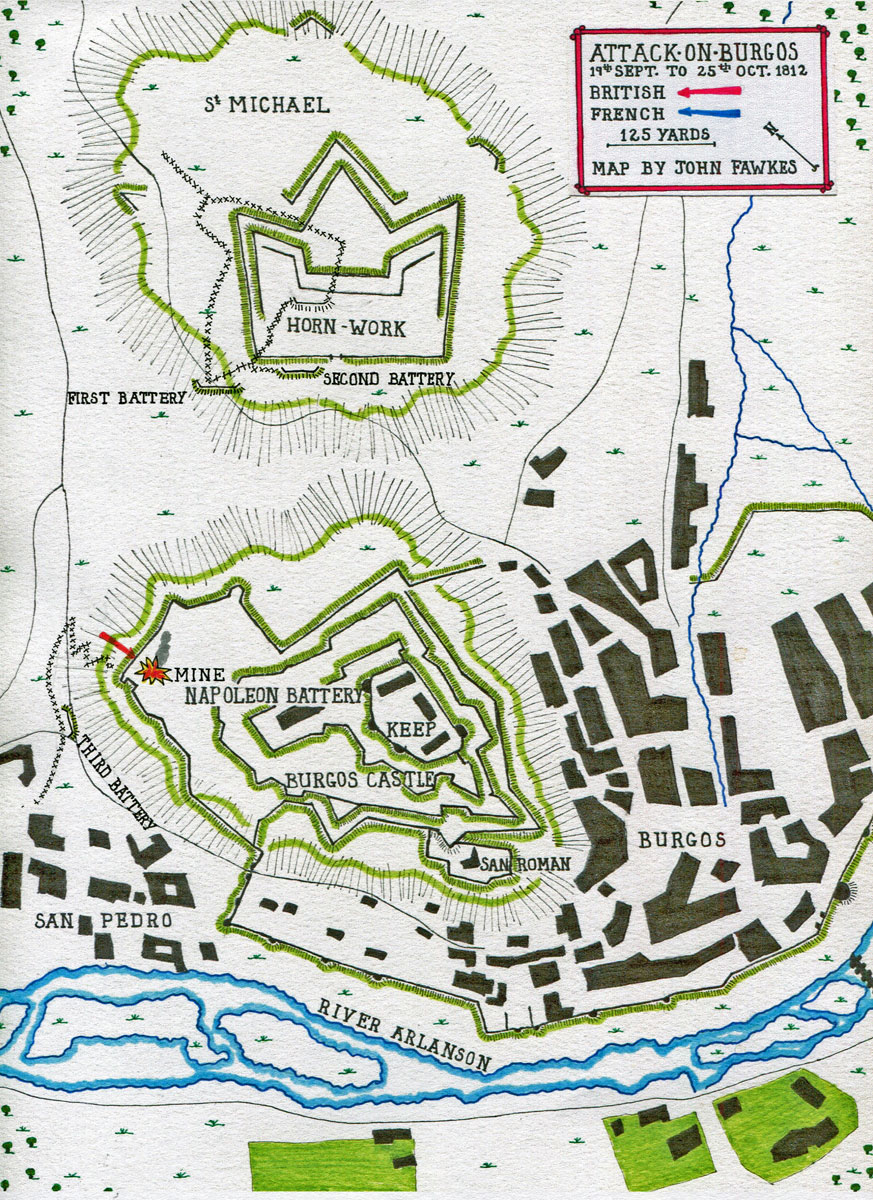

British attack on the St Michael horn-work on 19th September 1812: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

The Attack on the St Michael horn-work on 19th September 1812:

The 42nd Highlanders (Black Watch) provided a firing party to cover the main frontal assault, allotted to Pack’s Portuguese Brigade.

The light companies of the 2/24th, 1/42nd, 1/79th and the Guards, commanded by Major Somers Cocks, moved around the back of the horn-work, to prevent re-inforcement from the Castle and to make an additional assault into the rear.

42nd Highlanders attack the front of the French horn-work in the Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War

The attack was launched at 8pm in the dark and immediately encountered severe difficulties.

The frontal firing party was observed by the French and subjected to a damaging fire.

A party of Highlanders carried the escalading ladders into the ditch and propped them against the palisade, but the Portuguese troops failed to follow them and mount the ladders.

The Highlanders mounted the ladders in place of the Portuguese, but were insufficient in numbers and were driven back, leaving the attack on the front of the horn-work a failure.

At the rear of the horn-work, Major Somers Cocks’ men, under heavy fire from the Castle, scaled the palisade and drove the French back.

Leaving a small party to hold the sally-port in the rear palisade, Somers Cocks attacked the eastern bastion of the horn-work and overcame the French garrison.

Relieving French troops from the Castle forced their way through the horn-work rear sally-port, but were driven out by Somers Cocks’ troops, leaving the horn-work in British hands.

20th September 1812:

Wellington received news that a reinforcement of 7,000 men had reached the French Army of Portugal, with further drafts expected. It was necessary to press on with the attack on Burgos Castle without delay.

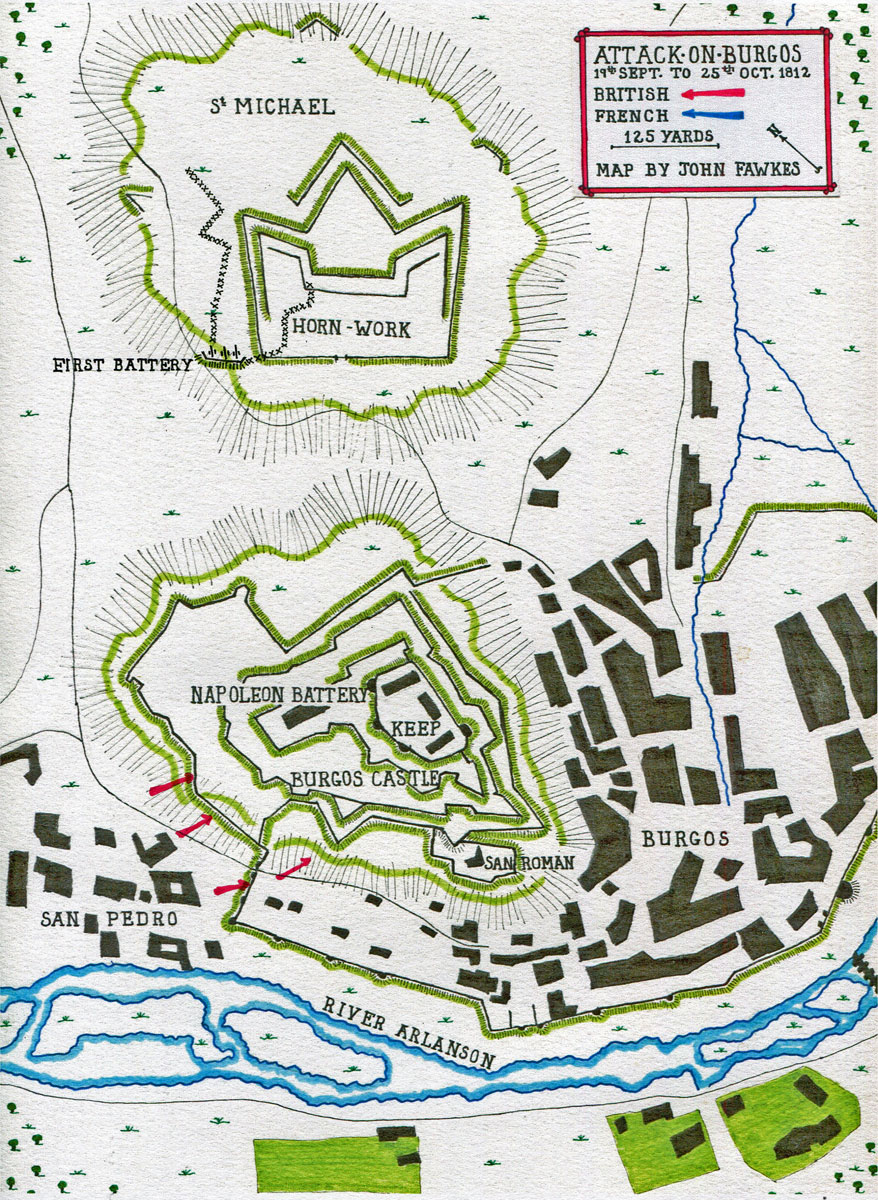

On the night of 20th September 1812, the British constructed their first battery, to the west of the horn-work.

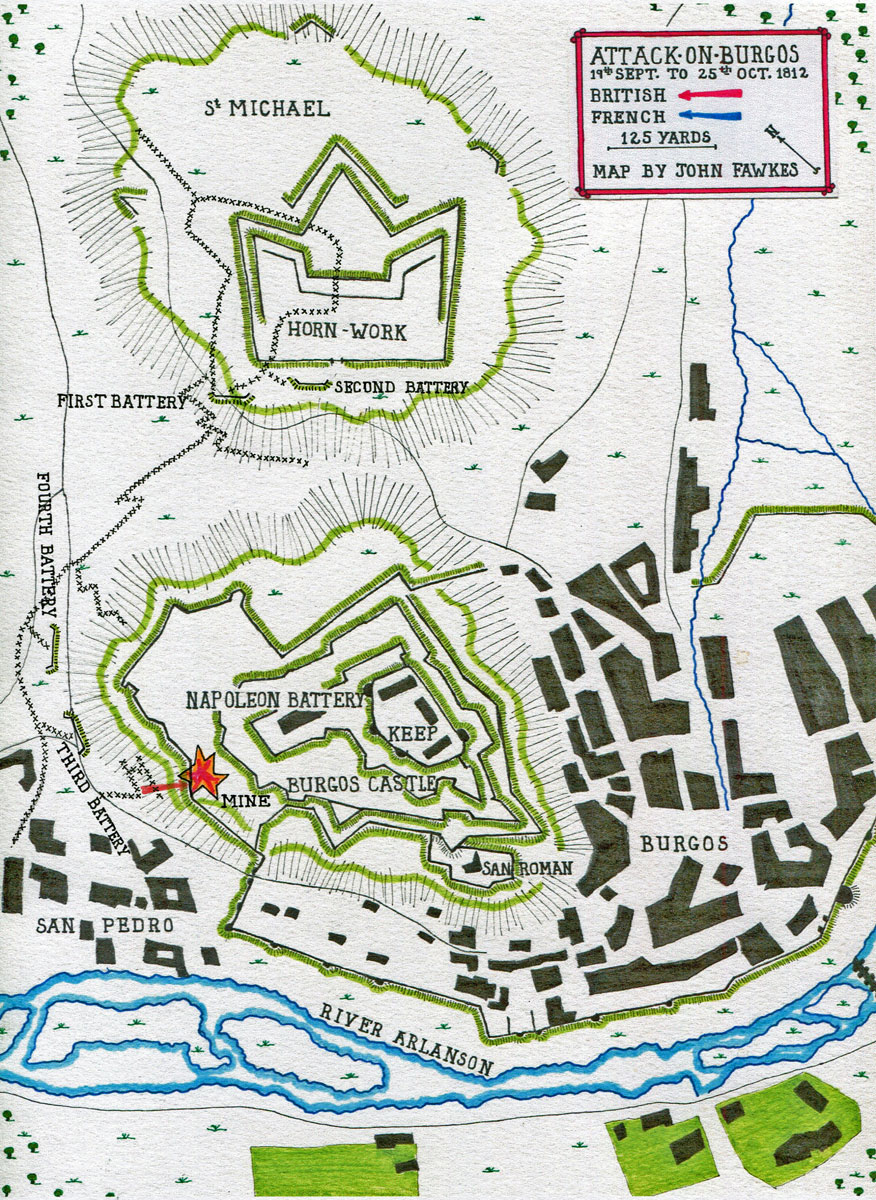

British and Portuguese attack on Burgos Castle on 22nd September 1812: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

Officer, 42nd Highlanders: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: statuette by Pilkington Jackson

22nd September 1812:

On 22nd September 1812, two 18 pounders and three field howitzers were mounted in the battery.

On the same night, an attack was launched by a Portuguese battalion on a weakly held part of the western palisade of Burgos Castle, while a force of 400 men, formed from all the battalions of the First Division, attacked a different part of the wall.

The attacks failed, the Portuguese refusing to advance and the British force all rushing into the ditch, when half were meant to have remained on the rim and provided covering fire. The French rolled down shells and rocks into the ditch and drove the British force back, with a loss of half their number.

French losses were reported as less than 20.

Mines:

The British now turned to mining the defences.

A parallel trench was constructed along the west side of Burgos Castle from the suburb of San Pedro.

Due to the heavy rain, the French garrison did not notice what was being built until dawn on 24th September 1812.

Thereupon, the French stationed sharp shooters in a palisade projecting from the fortifications and a telling fire was opened on the British troops working in the parallel trench, inflicting significant casualties.

Heavy howitzers were moved into the new battery, but were unable to hit the projecting palisade.

The fire of the howitzers and the 18 pounders in the second battery consumed the meagre store of British ammunition, forcing Wellington to send for more powder from Sir Home Popham’s Royal Navy squadron at Santander.

During the wait for the fresh powder supply, work was pressed forward on two mine galleries under the French fortifications on the western side of Burgos Castle.

At the same time, zig-zag approaches were built down the hill from the horn-work and a trench constructed to hold the infantry prior to an assault.

The work was slow due to the reluctance of the British troops to work under heavy fire in pouring rain and the active resistance of the French garrison.

British attack on Burgos Castle on 29th September 1812: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

British Infantryman: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War

29th September 1812:

With the completion of one of the mines, the assault was set for the night of 29th September 1812.

300 British troops were told off for the attack, with a forlorn hope of 1 officer and 20 men.

At midnight, the mine was fired, putting the French troops in the area in a panic and enabling the forlorn hope to gain the top of the parapet.

The following party of storming troops lacked a competent guide and lost its way in the dark, finally returning to its starting position, without making an assault and leaving the forlorn hope to abandon its position and retire.

Before the assaulting party could be redirected, the French were reinforced, making an assault no longer practicable.

Shortage of ammunition and heavy rain:

A siege requires a substantial store of artillery and small arms ammunition, due to the continual expenditure and Wellington’s ammunition was now exhausted, making further operations against Burgos Castle impossible until more ammunition was procured.

Heavy rain made the work of the besieging forces increasingly difficult and discipline deteriorated.

British and Portuguese working parties, other than the British Guards battalions, shirked their duties wherever possible.

A third battery was completed and mounted with three guns. These guns were knocked to pieces by French counter-battery fire before they could be brought into action.

Another battery, quickly built to the north of the third battery, suffered the same fate from the heavy plunging artillery fire of Burgos Castle.

The besieging force was now suffering severely from its lack of success, the rain that was falling and the heavy fire of the French artillery.

On the wet and stormy night of 2nd October 1812, the only troops to turn up for duty in the siege lines were the British Foot Guards, the others absenting themselves.

The two remaining 18 pounders were brought back to the first battery and the breach made by the first mine, now partially repaired by the French, was re-opened by bombardment. A second mine to the west of the first mine was completed.

British attack on Burgos Castle on 4th to 8th October 1812: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

4th October 1812:

At 5pm on 4th October 1812, the new mine was exploded and parties from the British 24th Regiment stormed the demolished works and the old breach, to be followed by other regiments.

The first line of the defences at these points was taken with casualties of 37 killed and 213 wounded or missing, including 9 officers.

This success was immediately followed with the building of trenches approaching the second French line. The British guns fired on this second wall, battering it down.

But once again the French preponderance in firepower and the lack of an adequate supply of ammunition brought Wellington’s troops up short.

Two of the British heavy guns were put out of action, while the heavy rain hampered the siege work.

French troops drive back a British assault during the Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War

8th October 1812:

At 2am on 8th October 1812, the French garrison sallied out and rushed the works under construction, achieving surprise. The approaches to the second wall were levelled by the French and large numbers of the besiegers’ tools were carried off.

The British troops rallied and counter-attacked the French, driving them back into Burgos Castle.

The British suffered 200 casualties in the attack and counter-attack, including the death of the recently promoted Colonel Charles Somers Cocks.

Wellington’s reserves of artillery and musket ammunition were now so low that active prosecution of the siege had to be reduced to attempting to set fire to the magazine in Burgos Castle, containing the French ammunition and supplies, by firing red-hot shot.

This attempt, maintained for 3 days, was unsuccessful. Small fires were generated in the roof of the magazine, easily put out by the French.

10th October 1812:

By 10th October 1812, ammunition for the British guns was so low that resort had to be made to collecting French projectiles from the battle field.

Eventually a convoy of powder arrived from Admiral Popham’s Royal Navy squadron at Santander and the British bombardment resumed.

A mine was begun towards the south-east corner of Burgos Castle at San Roman’s Church, used by the French as a storehouse.

On 11th October 1812, the British guns were almost out of ammunition and firing fell to a low level, enabling the French to repair the damage to the second wall.

15th October 1812:

On 15th October 1812, the British guns, comprising a howitzer and 2 damaged 18 pounders, opened fire from the second battery on the Napoleon Battery. These guns were quickly silenced by the heavier weight of artillery in the French defences.

The British fire was turned on the original breach in the second line. The breach was quickly widened and was nearly in a state where an assault could be made, when ammunition began to run out.

More ammunition arrived from Ciudad Rodrigo, but during the night, the heavy rain washed the battery walls away and the bombardment could not be resumed until they were rebuilt.

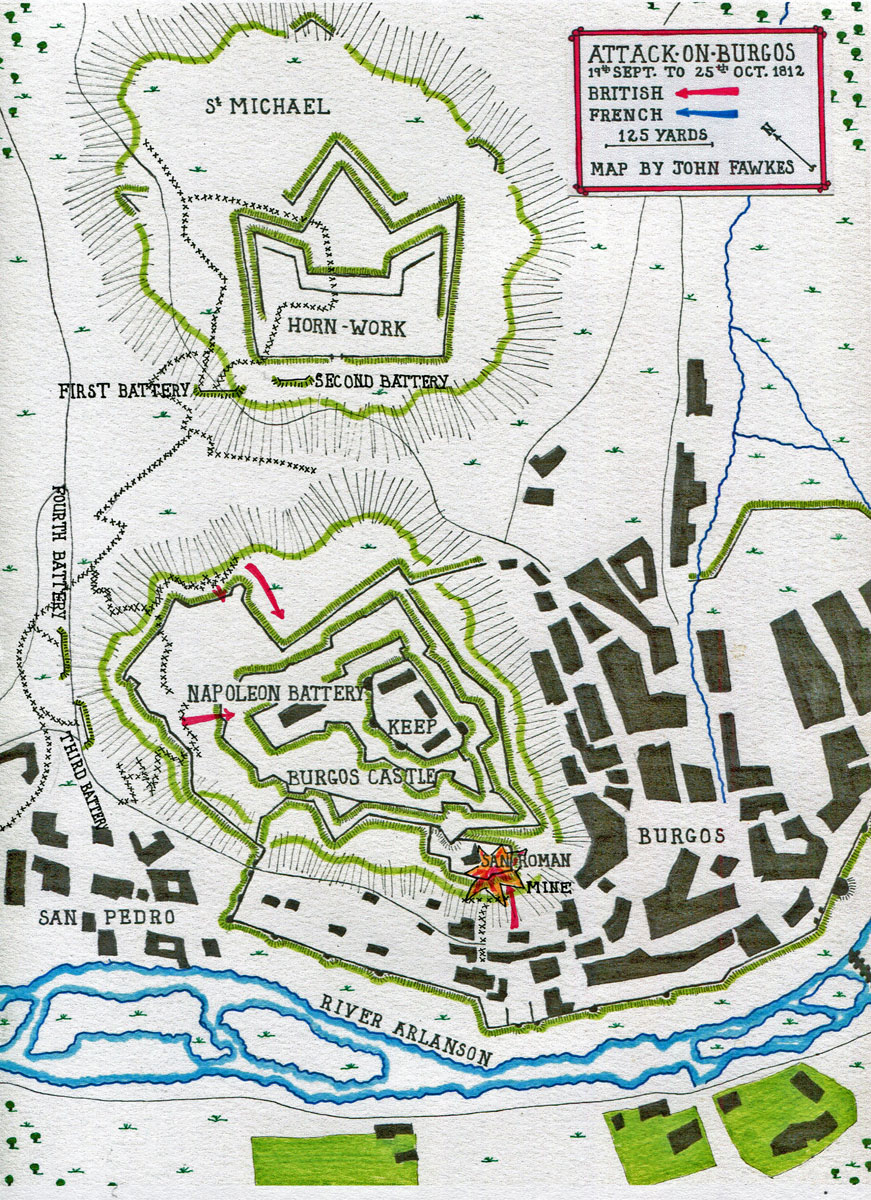

British, Spanish and Portuguese attack on Burgos Castle on 17th October 1812: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: map by John Fawkes

17th October 1812:

With firing resumed on the 17th October 1812, the few British guns managed to sweep away the retrenchments built by the French behind the breach and preparations were made for a final assault.

The attack was to be in three parts. The mine under the San Roman Church would be fired and a party of Spanish and Portuguese troops under Colonel Brown would rush the position.

Simultaneously, 200 troops of the Foot Guards would attack the eastern breach in the first line and then scale the second wall, while 200 of the King’s German Legion under Major Wurmb would assail the western breach in the second line.

The San Roman mine was fired and created a large hole in the defences, which was occupied by Brown’s Spanish and Portuguese troops.

The Guards advanced to the first line, passed it and formed up for the attack on the second line.

Half of Wurmb’s KGL party, having stormed into the second line, instead of turning and attacking a stockade on their flank, joined the Guards in their attack on the walls.

The other half of Wurmb’s party failed to appear, leaving an inadequate force to continue the assault.

The few KGL and Guards troops that penetrated the next line of French defences were killed and the rest driven back by a French counter-attack on their front and flanks.

The Coldstream Guards suffered losses of 60 killed and wounded including 4 officers, while the Third Guards lost 25 men, including 2 officers. The KGL lost 75 men, including 7 officers. Major Wurmb was killed.

San Roman Church, beneath Burgos Castle: Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War

22nd October 1812

On 22nd October 1812, Wellington abandoned the attack on Burgos Castle. The guns were withdrawn, the siege works destroyed, and the army fell back, leaving General Pack to continue the blockade of the French garrison.

Colonel Charles Somers Cocks, killed in the Attack on Burgos Castle between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War

Casualties in the Attack on Burgos:

British losses in the attack on Burgos Castle were some 92 officers and 1,972 soldiers, of whom 1/3 were killed.

French casualties were around 600 of whom ½ were killed.

Follow-up to the Attack on Burgos:

The Attack on Burgos is considered to be one of Wellington’s few failures in the field.

Following the unsuccessful Attack on Burgos, Wellington was compelled to retreat to Ciudad Rodrigo, his starting point in June 1812.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Attack on Burgos:

- Colonel Charles Somers Cocks: It is said that Wellington rarely showed grief, but did so at the military funeral of Colonel Somers Cocks. Somers Cocks began his Peninsular service with the 16th Light Dragoons. Somers Cocks was one of Wellington’s ‘Observing Officers’, carrying out reconnaissance behind French lines. The brilliance of his conduct earned him promotion to the majority in the 79th Cameron Highlanders and an acting colonel’s rank.

References for the Attack on Burgos:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Majadahonda

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Retreat from Burgos

Podcast on the Attack on Burgos between 19th September and 25th October 1812 in the Peninsular War: Wellington’s unsuccessful assault on the Spanish City following the Battle of Salamanca: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts