Wellington’s victory on 22nd July 1812 over the French army of Marshal Marmont, during the Peninsular War, leading to the re-capture of Madrid; also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapils

Podcast of the Battle of Salamanca: Wellington’s victory on 22nd July 1812 over the French army of Marshal Marmont, during the Peninsular War, leading to the re-capture of Madrid; also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

Podcast of the Battle of Salamanca: Wellington’s victory on 22nd July 1812 over the French army of Marshal Marmont, during the Peninsular War, leading to the re-capture of Madrid; also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Almaraz

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Garcia Hernandez

Marshal Marmont, French Commander at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Battle: Salamanca or Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

War: Peninsular War

Date of the Battle of Salamanca: 22nd July 1812

Place of the Battle of Salamanca: in Spain, between Ciudad Rodrigo on the Portuguese border and Madrid

Combatants at the Battle of Salamanca: British, Portuguese and Spanish against the French

Commanders at the Battle of Salamanca: Lieutenant General the Earl of Wellington against Marshal Marmont

Size of the armies at the Battle of Salamanca: 50,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish troops against 52,000 French troops.

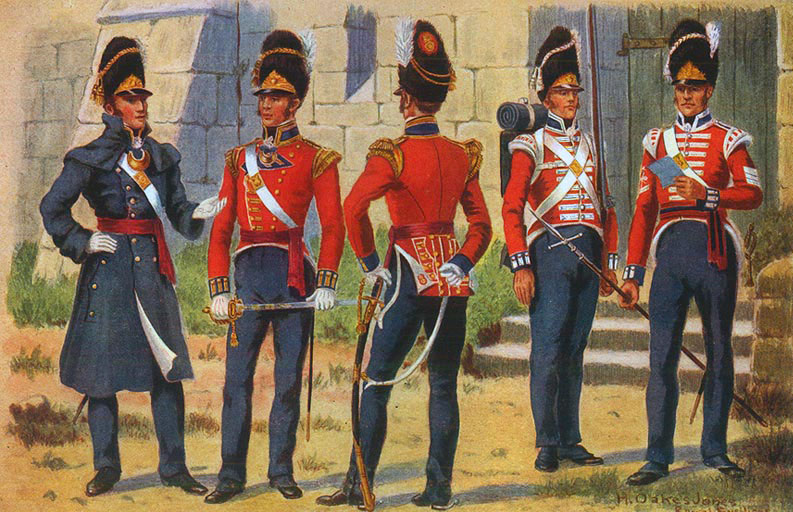

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Salamanca:

The British infantry wore red waist-length jackets, grey trousers, and stovepipe shakos. Fusilier regiments wore bearskin caps. The two rifle regiments wore dark green jackets and trousers.

The Royal Artillery wore blue tunics.

Highland regiments wore the kilt with red tunics and black ostrich feather caps.

British heavy cavalry (dragoon guards and dragoons) wore red jackets and black cocked hats. The change in uniform brought in during 1812 saw the British heavy cavalry adopt ‘Roman’ style helmets with horse hair plumes.

It seems uncertain when regiments changed from the old uniforms to the new 1812 uniforms. They may have fought at Salamanca in the old or the new.

British 5th Dragoon Guards {in the new uniforms) at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: picture by Richard Simkin

The British light dragoons wore light blue uniform coats and a leather helmet with a fur crest running front to back.

From 1812, the British light cavalry increasingly adopted hussar uniforms, with some regiments changing their title from ‘light dragoons’ to ‘hussars’.

The King’s German Legion (KGL) was formed largely from the old disbanded Hanoverian army. The KGL owed its allegiance to King George III of Great Britain, as the Elector of Hanover, and fought with the British army. The KGL comprised both cavalry and infantry regiments. KGL uniforms followed the British.

Tirailleur and Voltigeur of the French Infantry: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War: picture by Hippolyte Belangé

The Portuguese army uniforms increasingly during the Peninsular War reflected British styles. The Portuguese line infantry wore blue uniforms, while the Caçadores light infantry regiments wore green.

The Spanish army essentially was without uniforms, existing as it did in a country dominated by the French. Where formal uniforms could be obtained, they were white.

The French army wore a variety of uniforms. The basic infantry uniform was dark blue.

The French cavalry comprised Cuirassiers, wearing heavy burnished metal breastplates and crested helmets, Dragoons, largely in green, Hussars, in the conventional uniform worn by this arm across Europe, and Chasseurs à Cheval, dressed as hussars.

The French foot artillery wore uniforms similar to the infantry, the horse artillery wore hussar uniforms.

The standard infantry weapon across all the armies was the muzzle-loading musket. The musket could be fired at three or four times a minute, throwing a heavy ball inaccurately for a hundred metres or so. Each infantryman carried a bayonet for hand-to-hand fighting, which fitted the muzzle end of his musket.

The British rifle battalions (60th and 95th Rifles) carried the Baker rifle, a more accurate weapon but slower to fire, and a sword bayonet.

Attack of the British Heavy Dragoons at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Field guns fired a ball projectile, of limited use against troops in the field unless those troops were closely formed. Guns also fired case shot or canister which fragmented and was highly effective against troops in the field over a short range. Exploding shells fired by howitzers, yet in their infancy. were of particular use against buildings. The British were developing shrapnel (named after the British officer who invented it) which increased the effectiveness of exploding shells against troops in the field, by exploding in the air and showering them with metal fragments.

Throughout the Peninsular War and the Waterloo campaign, the British army was plagued by a shortage of artillery. The Army was sustained by volunteer recruitment and the Royal Artillery was not able to recruit sufficient gunners for its needs.

3rd King’s Own Dragoons: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War: picture by Charles Hamilton Smith

Napoleon exploited the advances in gunnery techniques of the last years of the French Ancien Régime to create his powerful and highly mobile artillery. Many of his battles were won using a combination of the manoeuvrability and fire power of the French guns with the speed of the French columns of infantry, supported by the mass of French cavalry.

While the French conscript infantry moved about the battle field in fast moving columns, the British trained to fight in line. The Duke of Wellington reduced the number of ranks to two, to extend the line of the British infantry and to exploit fully the firepower of his regiments.

Winner of the Battle of Salamanca: The British, Portuguese and Spanish

British order of battle:

Commander in Chief: Lieutenant General (local General) the Earl of Wellington

Cavalry: commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Stapleton Cotton

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Gaspard Le Marchant: 5th Dragoon Guards, 3rdand 4th Dragoons

5th Dragoon Guards (in the old uniforms) at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General George Anson: 11th, 12th and 16th Light Dragoons

3rd Brigade: commanded by Major General Victor von Alten: 14th Light Dragoons and 1stHussars, King’s German Legion

4th Brigade: commanded by Major General Baron Bock: 1st and 2nd Dragoons, King’s German Legion

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General D’Urban: 1st, 11th and 12th Portuguese Dragoons.

King’s German Legion 1st Dragoons: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Infantry:

First Division: commanded by Major General Henry Campbell

1st Brigade: commanded by Colonel Fermor: 1st/Coldstream Guards, 1st/3rd Guards, 1 company of 5th/60th Foot

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Wheatley: 2nd/24th, 1st/42nd, 2nd/58th, 1st/79th Foot and Co 5th/60th Foot.

3rd Brigade: commanded by Major General Baron Löw: 1st, 2nd and 5th Line Battalions, King’s German Legion.

Third Division: commanded by Colonel (local Major General) Pakenham

1st Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Wallace: 1st/45th, 74th, 1st/88th and 3 companies of the 5th/60th Foot.

2nd Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Campbell: 1st/5th, 2nd/5th, 2nd/83rd and 94th Foot.

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Colonel Manley Power: 1st and 2nd/9th, 1st and 2nd/21st Portuguese Line and 12th Caçadores .

Fourth Division: commanded by Major General (local Lieutenant General) Lowry Cole

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General William Anson: 3rd/27th, 1st/40th, 1 company of 5th/60th Foot.

2nd Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Ellis: 1st/7th, 1st/23rd, 1st/48th and 1 company of the Brunswick Oels.

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Colonel George Stubbs: 1st and 2nd/11th and 1st and 2nd/23rd Portuguese Line and 7th Caçadores .

Fifth Division: commanded by Major General (local Lieutenant General) Leigh.

1st Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Greville: 3rd/1st, 1st/9th, 1st and 2nd/38th Foot and 1 company of Brunswick Oels.

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Pringle: 1st and 2nd/4th, 2nd/30th, 2nd/44th Foot and 1 company of Brunswick Oels.

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Spry: 1st and 2nd/3rd, 1st and 2nd/15th Portuguese Line and 8th Caçadores .

Sixth Division: commanded by Major General Clinton.

1st Brigade: commanded by Major General Hulse: 1st/11th, 2nd/53rd, 1st /61st and 1 company of 5th/60th Foot.

2nd Brigade: commanded by Colonel Hinde: 2nd, 1st/32nd and 1st/36th Foot.

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General de Rezende: 1st and 2nd/8th, 1st and 2nd/12th Portuguese Line and 9th Caçadores .

Seventh Division: commanded by Major General Hope.

1st Brigade: commanded by Colonel Colin Halkett: 1st and 2nd Light Battalions King’s German Legion, 7 companies of Brunswick Oels.

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General von Bernewitz: 51st, 68th Foot and Chasseurs Britanniques.

Portuguese Brigade: commanded by Colonel Collins: 1st and 2nd/7th, 1st and 2nd/19thPortuguese Line and 2nd Caçadores .

Light Division: commanded by Lieutenant General Charles, Baron von Alten.

1st Brigade: commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Barnard: 1st/43rd Foot, 2nd/95th Rifles (4 companies), 3rd/95th Rifles (5 companies) and 3rd Caçadores .

2nd Brigade: commanded by Major General Vandeleur: 1st/52nd Foot, 1st/95th Rifles (8 companies) and 1st Caçadores .

Independent Brigades:

1st Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Pack: 1st and 2nd/1st, 1st and 2nd/16th Portuguese Line and 4thCaçadores .

2nd Brigade: commanded by Brigadier General Bradford: 1stand 2nd/13th, 1st and 2nd/14th Portuguese Line and 5thCaçadores .

Spanish Division: commanded by Major General De España: 2nd/Princesa, Tiradores de Castilla, 2nd/Jaen, 3rd/1st Seville and Caçadores de Castilla.

Artillery: Lieutenant Colonel Hoylet Framingham: 54 guns

Troops of Ross, Bull and Macdonald, Royal Horse Artillery.

Batteries of Lawson, Gardiner, Greene, Douglas, May and Arriaga (Portuguese).

French Dragoon: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

French order of battle at the Battle of Salamanca:

Commander in Chief: Marshal Marmont, Duke of Ragusa

Cavalry:

Light Cavalry Division: commanded by General Curto: 18 squadrons of 3rd Hussars, 22nd, 26th and 28th Chasseurs à Cheval (1st Brigade) and 13th and 14th Chasseurs à Cheval (2nd Brigade)

Heavy Cavalry Division: commanded by General Boyer: 8 squadrons of 6th, 11th, 19th and 25th Dragoons

Infantry:

First Division: commanded by General Foy: 8 battalions of 6th and 69th of the Line (1st Brigade) and 19th and 76th of the Line (2nd Brigade)

Second Division: commanded by General Clausel: 10 battalions of 25th Light and 27th of the Line (1st Brigade) and 50th and 59th of the Line (2nd Brigade)

Third Division: commanded by General Ferey: 9 battalions of 31st Light and 26th of the Line (1st Brigade) and 47th and 70th of the Line (2nd Brigade)

Fourth Division: commanded by General Sarrut: 9 battalions of 2nd Light and 26th of the Line (1st Brigade) and 4th Light (2nd Brigade)

Fifth Division: commanded by General Maucune: 9 battalions 15th and 66th of the Line (1st Brigade) and 82nd and 86th of the Line (2nd Brigade)

Sixth Division: commanded by General Brennier: 8 battalions of 17th Light and 65th of the Line (1st Brigade) and 4th Etranger and 22nd of the Line (2nd Brigade)

Seventh Division: commanded by General Thomières: 8 battalions of 1st and 62nd of the Line (1st Brigade) and 23rd and 101st of the Line (2nd Brigade)

Eighth Division: commanded by General Bonnet: 12 battalions of 118th and 119th of the Line (1st Brigade) and 120th and 122nd of the Line (2nd Brigade)

Artillery commanded by General Tirlet: 78 guns

Wellington at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: picture by William Heath

Background to the Battle of Salamanca:

On 9th May 1812, the Emperor Napoleon left France for Dresden to launch his invasion of Russia.

No longer able to supervise French operations in Spain, Napoleon passed command of the French armies in the Peninsula to his brother, Joseph, the nominal King of Spain, leaving Joseph to attempt to impose a common aim on the highly independent French senior officers commanding in the different parts of the country: particularly, Marshal Soult in Andalusia in the south of Spain and Marshal Marmont, commanding the ‘Army of Portugal’ on the north-east Portuguese border.

French Horse Artilleryman: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: picture by Belangé

The main French commands in other parts of Spain were the Army of Valencia under General Suchet in the south-east, the Army of Catalonia under General Decaen in the north-east, the Army of the Ebro under General Reille and the Army of the North commanded by General Caffarelli, in succession to Dorsenne.

King Joseph directly commanded the Army of the Centre, in Madrid, with Marshal Jourdan as his chief of staff.

Napoleon imposed on Joseph the principal obligation of combatting the Spanish guerrilla bands across the country. Joseph was to adopt a holding strategy against the British-Portuguese-Spanish regular forces under Wellington, until Napoleon returned victorious from Russia and was able finally to achieve a full victory in the Peninsula with his Grand Army.

Napoleon’s instructions assumed that Wellington would remain on the defensive.

However, following the capture by the British and Portuguese of the city fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz in the early months of 1812, Wellington advanced into Spain on the road to Madrid.

Joseph ordered Marmont to remain at Salamanca and Soult to re-inforce D’Erlon on the Guadiana River.

Both commanders refused to obey these instructions, Soult going so far as to say that he had received no direction to accept orders from Joseph.

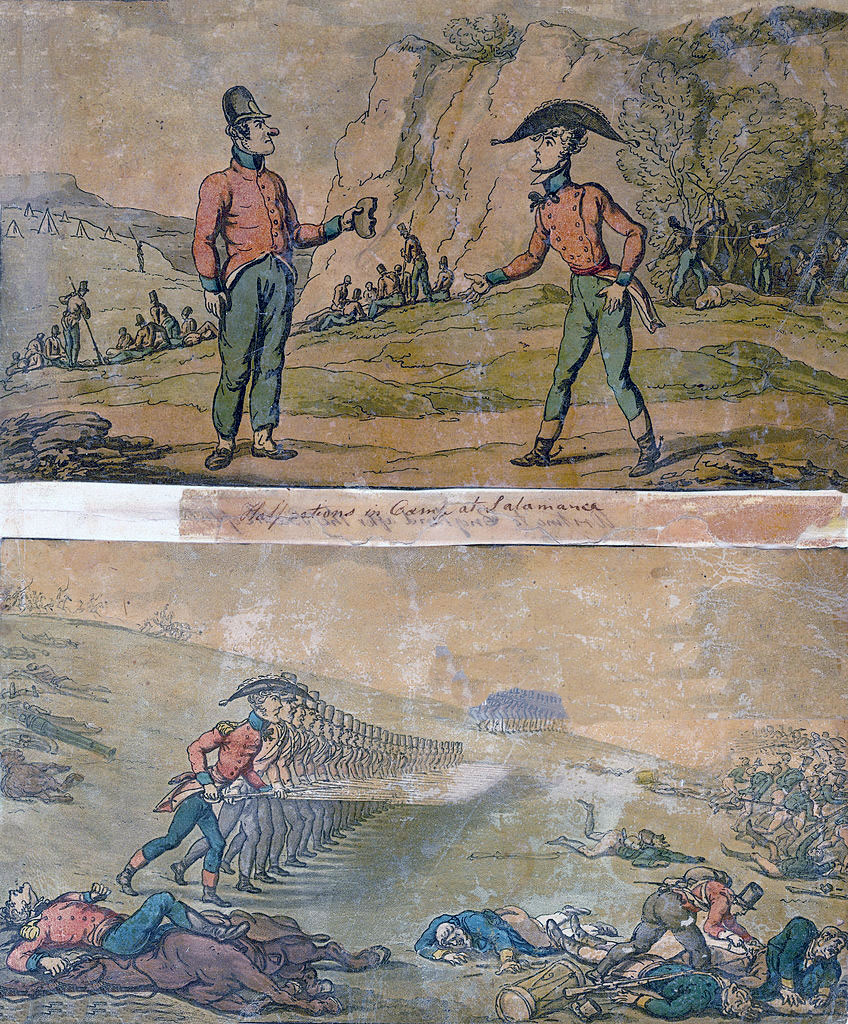

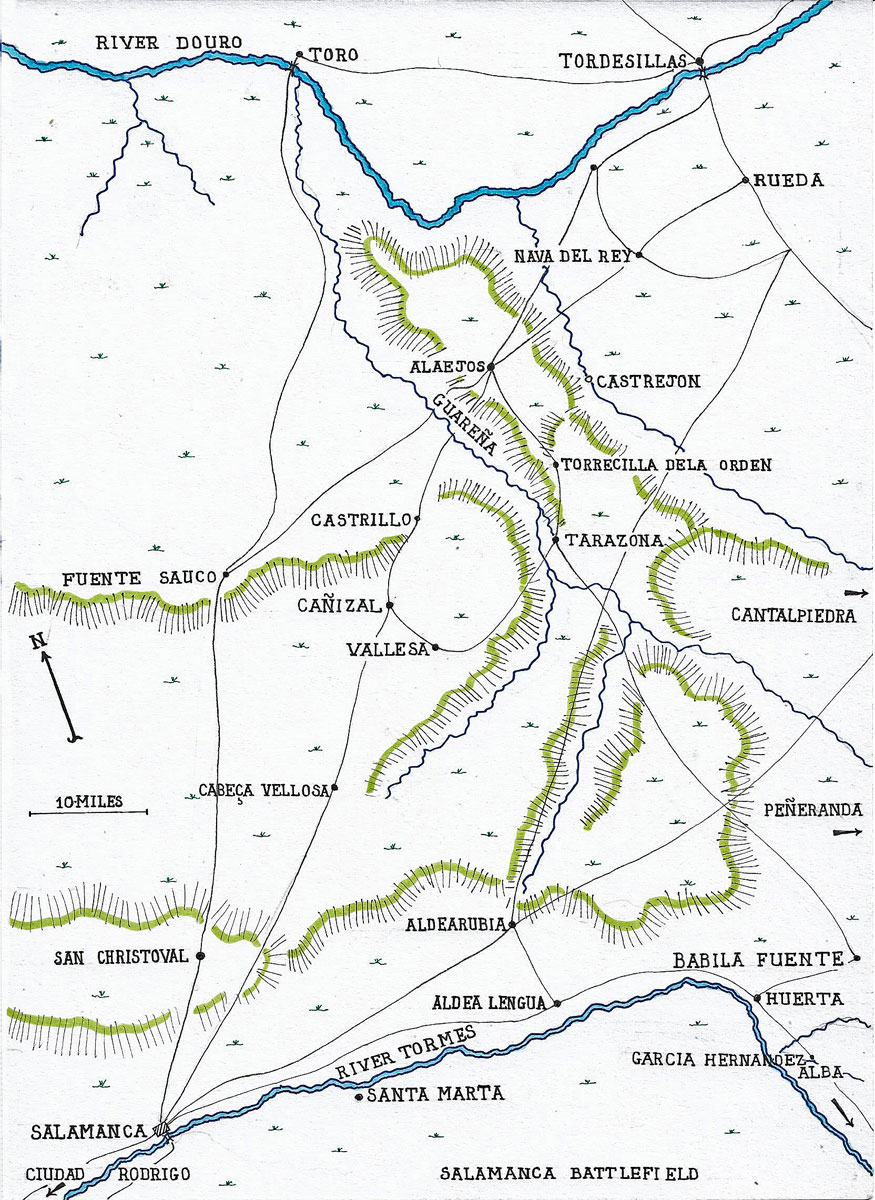

Map of the area of Spain between Salamanca on the River Tormes and Tordesillas on the River Douro: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: map by John Fawkes

Success for Wellington depended on the French armies remaining spread widely across Spain, rather than concentrating, in which case he would be heavily outnumbered. To this end, Wellington avoided an invasion of Andalucia, which would probably have caused Soult to leave the province and combine his army with Marmont’s Army of Portugal against Wellington.

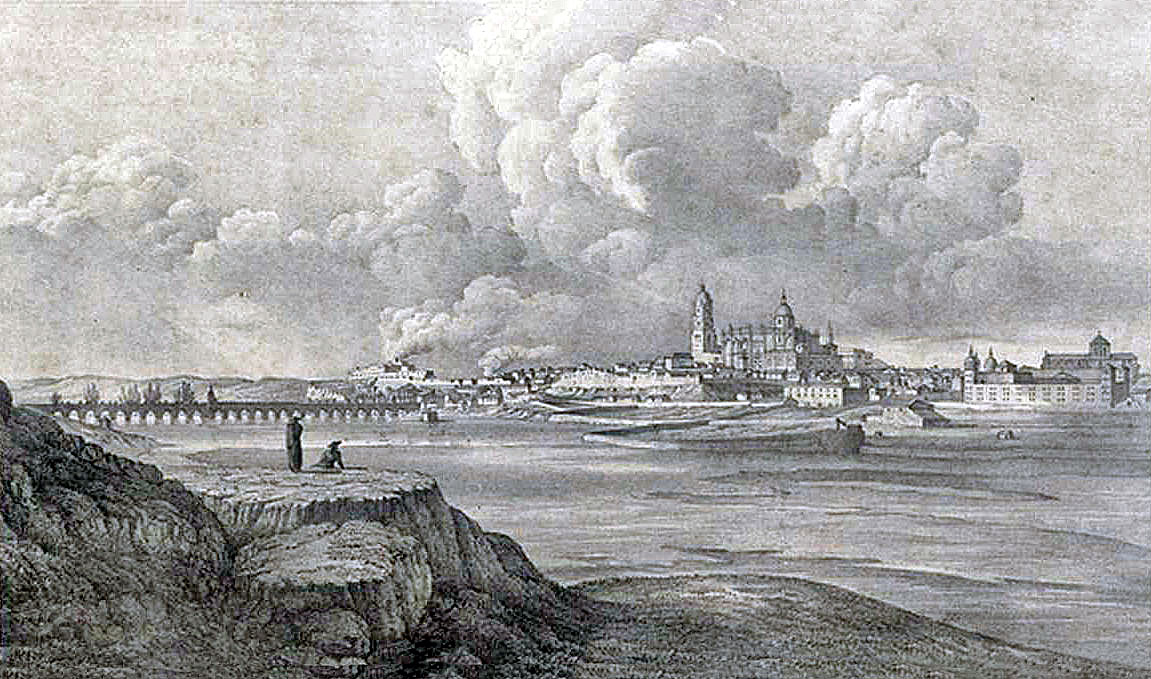

Salamanca: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: water colour sketch by Robert Kerr Porter

The British and Spanish authorities encouraged increased guerrilla activity across the whole of Spain, to tie down French troops and prevent their concentration at the point of Wellington’s attack, the road from Ciudad Rodrigo to Madrid, held by Marmont’s Army of Portugal.

Hill, with a substantial army, lay on the Guadiana River to the east of Badajoz, with the role of preventing D’Erlon or Soult from crossing the river and moving north in support of the Army of Portugal.

On 13th June 1812, Wellington crossed the Agueda River at Ciudad Rodrigo and advanced north-east up the road to Salamanca, with a British and Portuguese army of 43,000 men.

Wellington reached Salamanca on the River Tormes on 17th June 1812.

Lord Wellington entering Salamanca before the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Marmont’s two divisions in Salamanca withdrew to the north-east, towards the River Douro, leaving the city in Wellington’s hands, to the joy of the Spanish inhabitants.

The French retained a presence in Salamanca through their occupation of three forts, all conversions of convents, in the south-west corner of the city on the river bank.

Wellington was aware of these forts, but reports he received under-estimated their strength, leading to a failure to ensure that the army was accompanied by enough guns of sufficient size to enable a successful attack to be mounted upon them.

Nevertheless, on 17th June 1812, Wellington opened a bombardment of the three forts with some success.

On 20th June 1812, Marmont assembled five of his eight divisions at Fuente Sauco, 20 miles to the north-east of Salamanca and began an advance to relieve the French garrisons in the three forts.

Convent of San Vincente, converted to a fort by the French at Salamanca: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Wellington, receiving reports of Marmont’s approach, abandoned the attack on the forts and assembled his army on the Heights of San Cristobal to the north of Salamanca.

Marmont brought his troops to the foot of the San Christoval Heights. Wellington was tempted to launch an attack on Marmont’s divisions, but decided against it.

Over the night of 20th/21st June 1812, Marmont’s remaining three divisions marched up, giving him a force of 35,000 men.

Marmont, in turn, considered an assault on Wellington’s army, but a council of war of his generals advised against it and, on 22nd June 1812, after some fighting over an outlying hill, taken and lost by the French, Marmont’s army marched away to the east-north-east, 9 miles to Aldearubia, a position that commanded the ford of Huerta on the River Tormes and enabled Marmont to threaten Wellington’s right flank.

Attack on the French forts in Salamanca before the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Wellington moved forward, conforming to Marmont’s position, with his right on the Santa Marta ford over the River Tormes.

On 24th June 1812, two French divisions, with cavalry and guns, crossed the River Tormes and moved south, threatening Wellington’s communications.

General Graham advanced to meet this force with two British divisions and the heavy cavalry brigades of Bock and Le Marchant and the French withdrew across the Huerta ford.

Again, Wellington resisted taking advantage of the exposed position of the two French divisions and did not attack.

The assault on the three Salamanca forts, held by the French, resumed and, on 27th June 1812, the French garrisons surrendered, with 800 French troops becoming prisoners.

Marmont withdrew the 40 miles to Tordesillas, on the River Douro, on 27th June 1812 and began crossing the river on 2nd July 1812, making sure that the bridges outside Tordesillas were destroyed.

Wellington’s army pursued the French. The advanced guard of British dragoons and horse artillery encountered a strong force of French cavalry and infantry in Rueda, which they drove back.

Wellington despatched reconnaissance parties along the River Douro to see if there were any fords not guarded by the French, which might be used to cross the river, while his main body took up positions in the rear of the French crossing at Tordesillas.

British Infantry advancing at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Marmont was expecting substantial reinforcements from Caffarelli’s Army of the North, in accordance with King Joseph’s direction to Caffarelli. None arrived, giving rise to a sharp correspondence between Marmont and Caffarelli.

Marmont was forced to turn to King Joseph’s Army of the Centre for assistance, which Joseph, alone among the senior French commanders, was determined to give, to save his capital, Madrid.

On 9th July 1812, Joseph marched with 14,000 men to join Marmont. However, both copies of Joseph’s letter informing Marmont of his actions were intercepted by Spanish guerrillas, giving the information to Wellington, but leaving Marmont in ignorance.

Wellington accompanying the Fifth Division in its attack on Maucune’s Division at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Marmont was under pressure from his officers to take the offensive, after the failure to relieve the three French forts at Salamanca and the loss of their garrisons.

Between 3rd and 16th July 1812, Marmont’s army and Wellington’s three divisions remained inactive, on either bank of the River Douro between Toro and Tordesillas.

On 16th July 1812, Marmont conducted a feint move at Toro, Bonnet’s division crossing the River Douro, then crossing back during the following night and destroying the repaired bridge.

On 17th July 1812, the whole of Marmont’s army crossed the River Douro at Tordesillas and force marched the 10 miles to Narva del Rey, intending to circumvent Wellington’s right flank.

Wellington ordered his centre and left to concentrate around the town of Cañizal, but, only partly deceived by Bonnet’s feint crossing, the British Light and Fourth Divisions and Anson’s cavalry brigade, led by Cotton, moved to the east to Castrejon, in Marmont’s line of advance.

On 18th July 1812, skirmishing took place between Cotton’s cavalry and the advanced French picquets, causing Wellington to move three brigades of cavalry, in support of Cotton and the Fifth Division, to Torrecilla de la Orden, further south in Marmont’s line of march.

Advancing French cavalry attempted to take some British guns and a further skirmish took place, with Wellington and Beresford and their staffs forced to fight their way clear, to avoid capture.

Marmont brought his infantry up to Alaejos and Wellington ordered a withdrawal by Torrecilla de la Orden.

The two armies then marched in parallel columns in the blistering heat, each attempting to overtake the other, for some ten miles to the Guareña River.

The British reached the Guareña first and the troops rushed to drink from the river.

The French brought up guns and opened fire on the British, causing the British infantry to cross the river and withdraw up the hill on the far side.

Cathedral of Salamanca: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

The action at Castrillo:

The three British divisions continued on up the hillside and took position between Castrillo and Cañizal.

Wellington’s remaining divisions formed up, further to the right, at Vallesa.

The French resumed the advance in two columns.

Clausel, commanding the right column, sent a force of cavalry across the ford over the Guareña River near Castrillo, supported by an infantry battalion and 3 guns.

The French cavalry were engaged by Alten’s cavalry brigade and driven back on the infantry, with a loss of 94 prisoners, including the brigade commander, General Carrié.

The British 3rd Dragoons joined Alten’s brigade and Alten renewed his attack, to be in turn driven back.

The 27th and 40th Regiments from the British Fourth Division came up and dispersed the French infantry battalion at the point of the bayonet.

A squadron of KGL Hussars followed up the infantry success, taking 150 prisoners.

In this action, Alten’s cavalry suffered casualties of 145 killed, wounded and captured. The casualties of the 27th and 40th Regiments were 140 killed, wounded and missing.

Casualties for the whole of Wellington’s army during the day’s fighting were 442 killed, wounded and missing.

French casualties are unknown but are likely to have been much the same.

Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

The march continues:

Both sides rested during the morning of 19th July 1812. In the afternoon Marmont marched off to his left, to Tarazona, along the eastern branch of the Guareña River, while Wellington matched his movements on the south side, moving to the heights around Vallesa.

On 20th July 1812, instead of launching an attack, as Wellington expected, Marmont marched on to Cantalapiedra and crossed the Guareña River there, outflanking Wellington’s position.

Both armies resumed the marching contest, heading in parallel columns for the River Tormes.

The French outmarched the British, causing Wellington to abandon the race and turn westwards towards Aldearubia.

Only when night fell did the flare of the camp fires reveal to its opponents where each army was situated.

Marmont’s camp fires showed the French to be at Babila Fuentes, overlooking the ford across the River Tormes at Huerta. Wellington was outmanoeuvred.

British 12th Light Dragoons in the charge at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: picture by B. Granville Baker

Wellington brought forward his other divisions, assembling his army at Cabeça Vellosa, some fifteen miles to the north-west of the French encampment.

During the hurried forced marches of the day, the British and Portuguese forces lost some 400 stragglers taken by the French cavalry, with a significant number of D’Urban’s Portuguese cavalry mistakenly shot by the British Third Division.

On 21st July 1812, Wellington returned to his positions on the San Christoval heights. From there he wrote to the Spanish and British governments, stating that he would remain to cover Salamanca for as long as possible, but could not allow the French to sever his communications with Ciudad Rodrigo. Wellington was forced to contemplate the abandonment of his offensive and retreat back into Portugal.

A grave mishap now befell the Allied army. The Spanish General, Carlos D’España, holding the important crossing of the River Tormes at the town of Alba de Tormes, abandoned his post and withdrew. Further, through fear of Wellington’s reaction to this dereliction, D’España failed to warn Wellington of his actions.

Informed of D’España’s withdrawal, Marmont extended his position up the Tormes, so that his left flank lay at Alba, threatening Wellington’s communications with Ciudad Rodrigo.

City and Bridge of Salamanca: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

The French cross the River Tormes:

Generals Foy and Clausel urged Marmont to cross the River Tormes, which he did at midday on 21st July 1812, by way of the Huerta and Encinos de Abajo fords.

The advanced French cavalry occupied the villages of Calvarassa de Arriba and Nuestra Senhora de la Pena, on the heights to the west of the River Tormes.

Informed of the French movement across the Tormes between Huerta and Alba, Wellington put his army in motion, other than the Third Division and D’Urban’s Portuguese Cavalry, which remained to counter the French still at Babila Fuente.

The remainder of Wellington’s divisions crossed to the south bank of the River Tormes by the Salamanca bridge and the Santa Marta ford and took up an extended position concealed behind the ridge running south from the River Tormes at Santa Marta to a rugged hill called the Lesser Arapil.

The British, Portuguese and Spanish troops were still in motion, when a violent thunder-storm broke. So heavy was the rain that the River Tormes rose significantly, shoulder high for the Light Division soldiers crossing the ford of Santa Marta. The storm raged throughout the night, flooding entrenchments and causing horses to bolt.

That night, news reached Wellington that reinforcements of 1,700 cavalry and 20 guns, sent by Caffarelli’s Army of the North, were marching to join Marmont. King Joseph was also on the march to join Marmont, with 13,000 troops. Neither force would reach Marmont for several days.

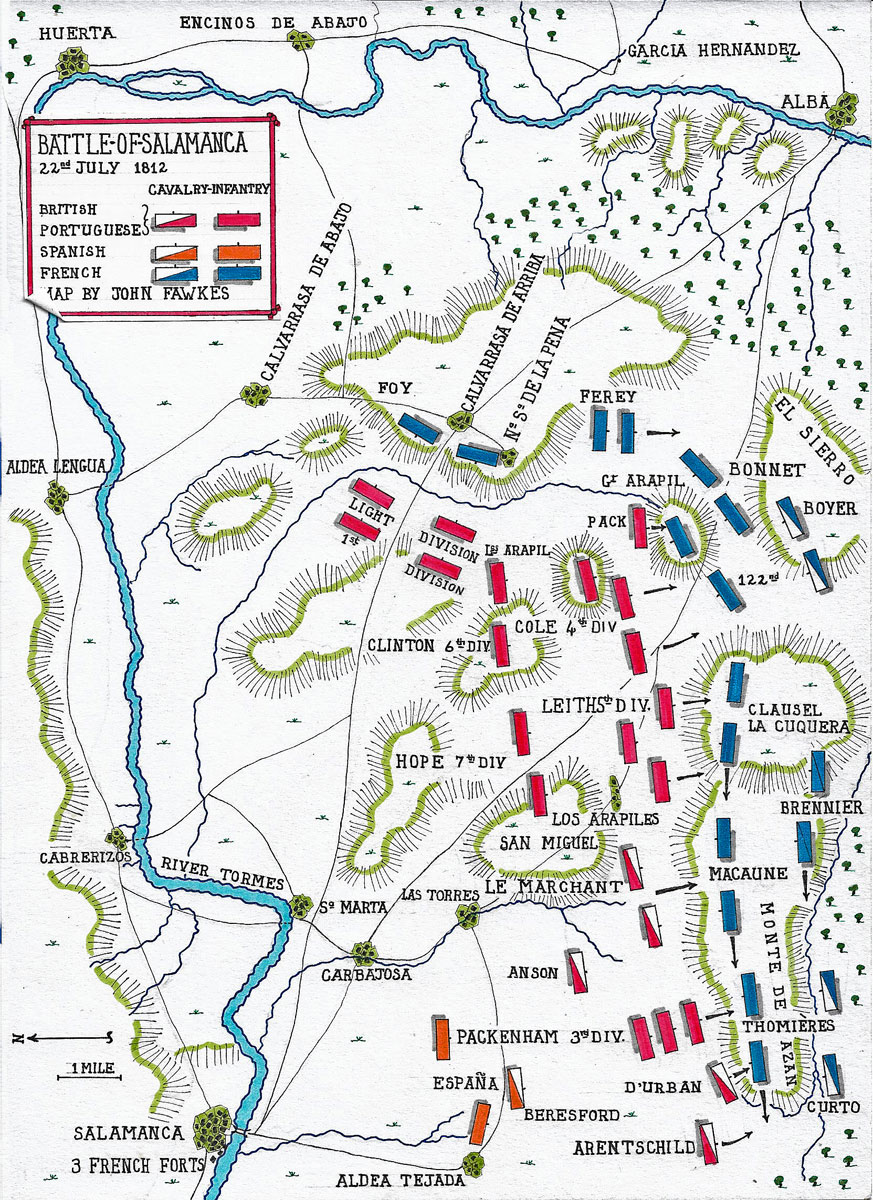

Map of the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: battle map by John Fawkes

The Battle of Salamanca:

At dawn on 22nd July 1812, Marmont rode to the heights of Calvarassa de Arriba to review the position of his army.

To his front could be seen the British Seventh Division, formed across the road to Salamanca.

Directly to the west, in the distance, was a small force ascending the hill towards Aldea Tejada. Marmont took this to be the escort of a baggage train heading towards Ciudad Rodrigo.

Examination of the remaining countryside revealed some parties of horsemen, but no substantial bodies of troops, other than a ‘small occupying force’ on the heights of San Cristobal, north of the River Tormes.

Marmont concluded that Wellington was in the process of retreating towards Ciudad Rodrigo.

The French were unable to see the line of Wellington’s divisions concealed behind the ridge of high ground that stretched from the two Arapils, directly in front of them, north to the Santa Marta ford on the River Tormes.

Marmont concluded that the British division he could see, the Seventh Division, was Wellington’s rear guard and the rest of Wellington’s army was moving through Salamanca to join the Ciudad Rodrigo road at Tejares.

Marmont rejected the idea of a direct attack and, after consideration, decided to march around Wellington’s southern flank to cut him off from Ciudad Rodrigo.

The two features, the Lesser Arapil and the Greater Arapil, lie at the southern end of the ridge running north to south from Santa Marta on the River Tormes.

Charge of the British Light Dragoons at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War

The Lesser Arapil rises steeply to about 100 feet and was where Wellington positioned the right-hand end of his line.

The Greater Arapil lies half a mile to its south and is equally steep, but higher. To the west of the Arapils stretches a wide area, with the village of Los Arapiles at the western end and a hill, the Teso of San Miguel, behind the village.

To the south lies the hill of La Cuquera.

The area was full of folds and hollows which would conceal the movement of troops involved in the ensuing battle.

Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Marmont’s intention was to march around the southern flank of Wellington’s army and either attack it in the rear or cut its communications with Ciudad Rodrigo. His advance would be through the gateway created by the Lesser and Greater Arapils into the area beyond.

Acting on Marmont’s order, General Bonnet sent troops to occupy the two Arapils.

Wellington, seeing the French on the move and equally appreciating the importance of the Arapils, despatched the Portuguese 7th Caçadores to take the Lesser Arapil.

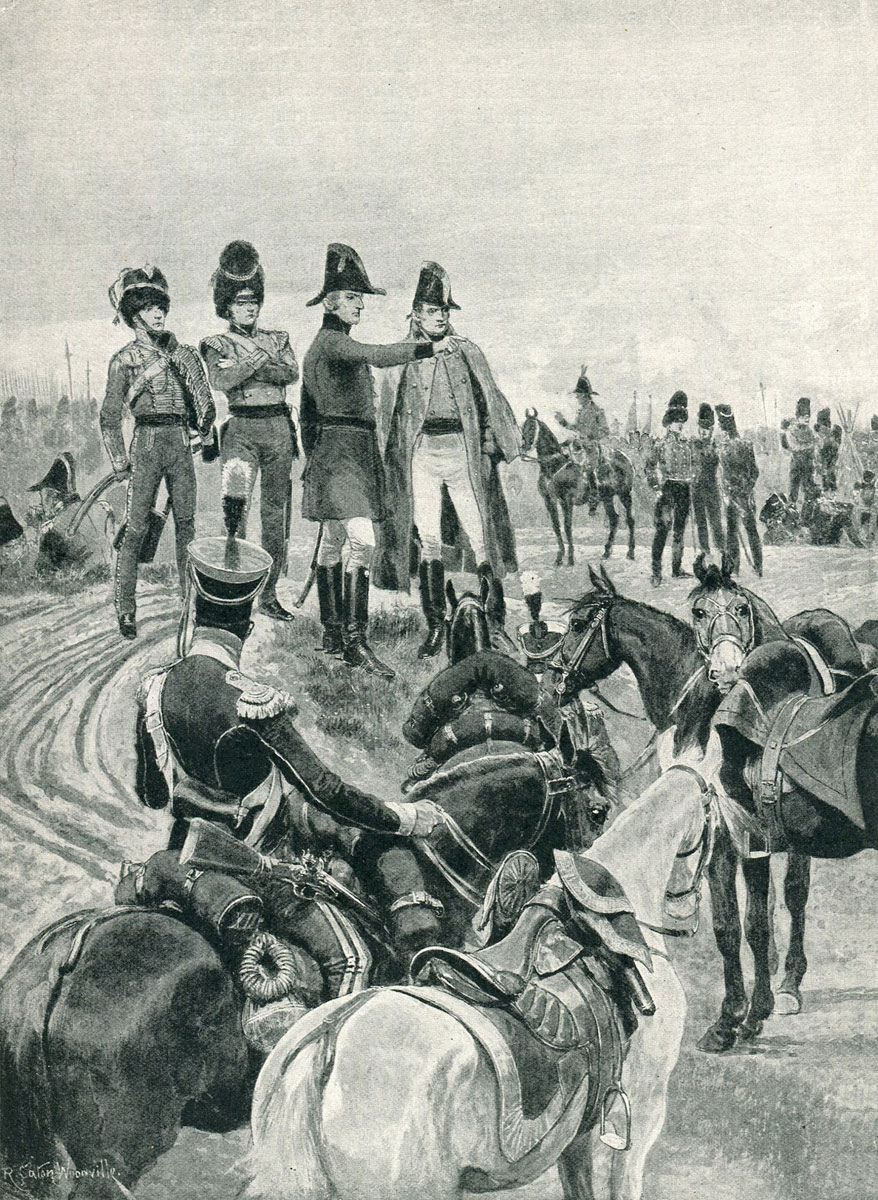

Wellington instructing Pakenham to begin the attack on the French columns at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Bonnet’s men occupied the Greater Arapil, but were beaten in the race for the Lesser Arapil by the 7th Caçadores.

The French carried guns to the top of the Greater Arapil. The hill was too steep to move guns in any other way. Bonnet’s Division formed behind the hill.

In the meantime, Marmont continued with his deployment.

Foy’s division remained on the Calvarrasa de Arriba plateau, supported by Ferey’s division, with Boyer’s Dragoon Division in the rear.

The divisions of Clausel, Sarrut, Maucune and Brennier, amounting to 20,000 men, were ordered to assemble in the rear of the Calvarrasa de Arriba position, on the edge of the forest that lay behind the high ground.

Thomières’ division moved forward to the El Sierro, an area to the south-east of the Greater Arapil, with Curto’s light cavalry division in support.

With his troops in these positions, Marmont waited to see what Wellington would do.

To counter the French moves, Wellington ordered the light companies of the British Foot Guards to occupy the village of Los Arapiles, with Cole’s Fourth Division in support on the Teso de San Miguel and on the Lesser Arapil, which was occupied by Anson’s Brigade.

Pakenham’s Third Division was ordered to cross the River Tormes to the south bank and march south-west, to take position behind Aldea Tejada, 3 miles north of Arapiles.

The Light Division moved forward to a position on the heights confronting Foy’s division at Nuestra Señora de la Pena, with the First Division in support.

The Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Divisions remained concealed on the reverse slope of the ridge Wellington’s army had occupied the previous night.

While the French columns were marching to take up their positions, Lawson’s battery of field artillery came up and opened fire. A heavy French fire was returned, silencing the British guns.

No further action took place until 11am, when Wellington brought forward the First Division, to drive the French off the Greater Arapil. Marmont was on the hill and, concluding that Wellington was launching a general assault, galloped back to his main body.

In fact, no British attack was delivered, as Beresford persuaded Wellington that this was not the moment.

5th Dragoon Guards pass Lord Wellington: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: picture by Richard Simkin

The heavy rain storms of the night gave way to a hot sunny morning and Marmont was able to see a cloud of dust in the direction of Salamanca, moving from the north-east to the south-west.

Marmont’s conclusion was that Wellington was re-inforcing his right wing, prior to beginning a general retreat towards Ciudad Rodrigo.

In fact, the dust cloud was generated by Pakenham’s Third Division in its march from the River Tormes at Cabrerizos to Aldea Tejada.

In response to the moves he took Wellington to be making, Marmont re-positioned the troops of his centre and left wing, moving forward the divisions of Maucune and Thomières, Brennier’s Division taking the place of Thomières’, with Clausel’s Division in reserve. The 122nd Regiment of the Line from Bonnet’s Division occupied the ground to the south-west of the Greater Arapil, to complete the line.

88th Regiment, the Connaught Rangers, at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Instead of adopting the position ordered by Marmont, Maucune took his division further to the west, while Thomières, instead of supporting Maucune, overtook him, also marching to the west. Fortescue’s conclusion is that the French generals assumed there was a resumption of the rival marching of the previous day and were determined to catch up with the retreating British.

In fact, unknowingly, the French army was making the classic battlefield error of marching across the front of the enemy, thereby exposing its flank to attack, when support for the threatened wing was unlikely to be available.

Wellington was having lunch in a farmhouse, when he was summoned by his staff to see the French movements. Wellington abandoned his lunch and rode to the Lesser Arapil for a better view, where, at the sight of the French left wing marching away from the support of the French centre and right wing, Wellington is reported as making the historic comment to his Spanish aide-de-camp, ‘M. d’Alava. Marmont est perdu!’ (M. d’Alava. Marmont is lost).

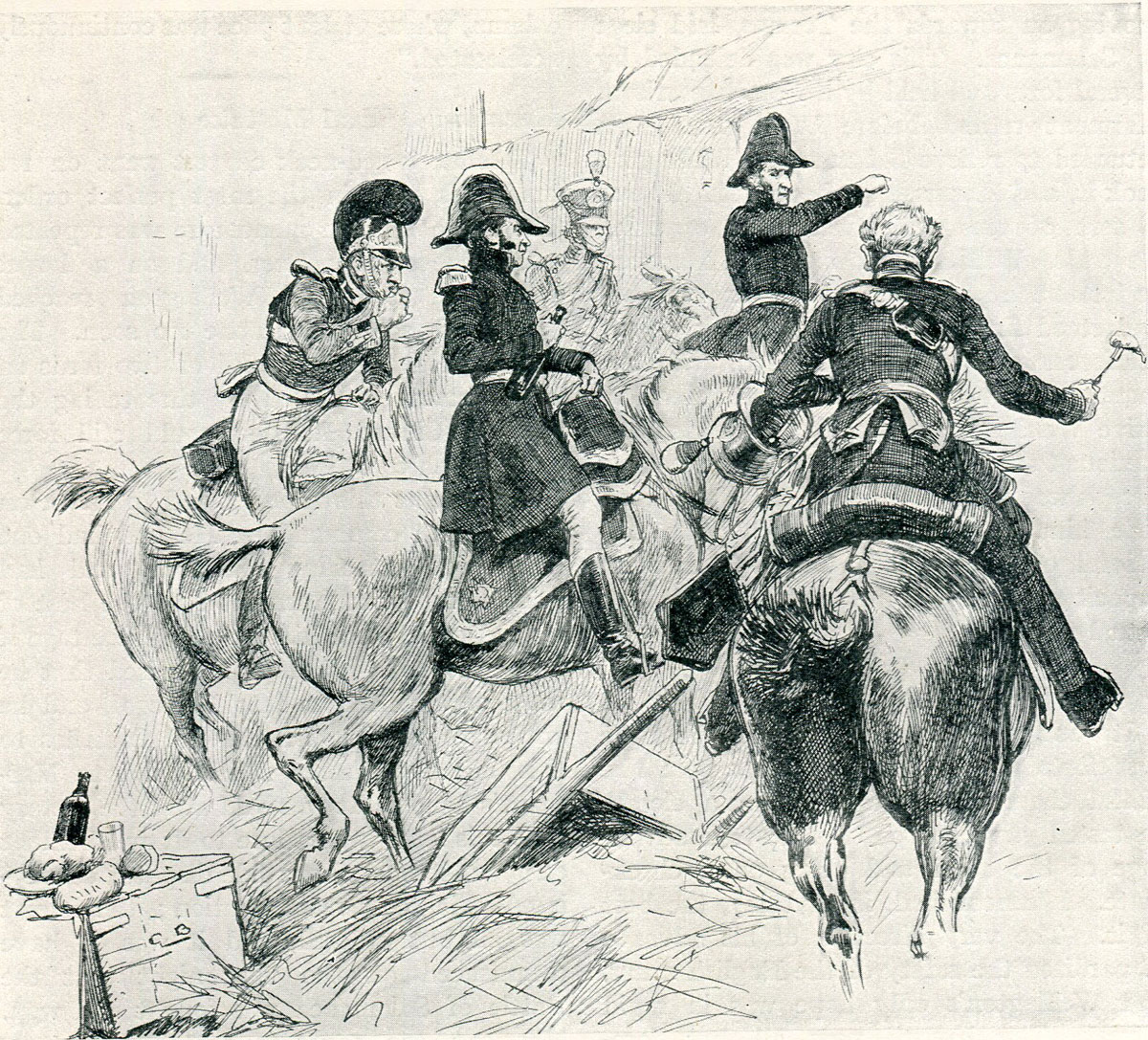

Wellington riding out of the farmyard to begin the attack on the French columns at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Wellington rapidly made the deployments to bring his prediction about, bringing up the Fifth Division behind the Fourth Division, with the Seventh and Sixth Divisions in support.

Beresford’s Portuguese Cavalry Brigade and Le Marchant’s British Heavy Cavalry Brigade formed behind the right rear of the Fifth Division.

Seeing the deployment of the British divisions on his left, Marmont sent urgent messages for the divisions of Ferey and Sarrut to march to the support of Thomières, Maucune and Brennier.

In the meantime, Wellington rode to Aldea Tejada on his extreme right, where he ordered Pakenham’s Third Division forward to attack the leading French divisions of Thomières, Maucune and Brennier, as they marched to the north-west.

Pakenham’s force, comprising his Third Division and Alten’s Cavalry Brigade, advanced over some 2½ miles in four columns, Alten’s cavalrymen forming the right-hand column.

D’Urban, riding in advance of his men, encountered Thomières’ leading battalion marching hard up the hill, with no covering cavalry or light infantry scouts. The French battalion was already beyond Pakenham’s front.

D’Urban brought forward his Portuguese cavalry and attacked the French battalion in the front and rear. The French infantry broke and escaped up the hill with heavy losses.

The rest of Thomières’ Division hurried on up the hill, with guns and skirmishers attempting to halt Pakenham’s advance.

88th Connaught Rangers capturing the ‘Jingling Johnnie’ from the French 101st Regiment at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Major Murphy, commanding the 88th, was shot down, upon which, the 88th and the rest of Wallace’s Brigade charged the French division, dissolving it into a mob of panic-stricken fugitives.

In the centre of the line, the artillery on each side opened a heavy bombardment, with Marmont himself wounded by the gunfire, as was General Bonnet, depriving the French army, at a critical moment, of its commander-in-chief and his deputy. It took some time for Clausel to be found and informed that he was now in command.

Wellington waited for Packenham’s Third Division to be heavily engaged on the right, before committing the troops in his centre. This left the British Fifth Division lying down in the open plain, exposed to a heavy French artillery fire, while Leith, the divisional commander, rode along the front of his troops to encourage them. French sharp shooters delivered multiple attacks on Arapiles village.

9th Royal Fusiliers: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapils

Satisfied with the progress of Pakenham’s attack, Wellington ordered Leith to form his division in two lines; the front line comprising the 1st Royals, 9th, 38th and 4th King’s Own; the second comprising the 4th King’s Own, 30th, 44th and 58th with Spry’s Portuguese Brigade.

Once Bradford’s Portuguese Brigade was in position on their right, the Fifth Division moved forward.

For a time, the commander-in-chief rode with the division as it advanced, before leaving to conduct the battle elsewhere.

The French artillery and skirmishers continued to fire on the Fifth Division, as it advanced up the slope. Reaching the brow, the British and Portuguese infantry came into the view of Maucune’s Division. The French were waiting in line and met them with a volley.

Leith’s men fired a volley in reply and charged Maucune’s Division, which dissolved in flight.

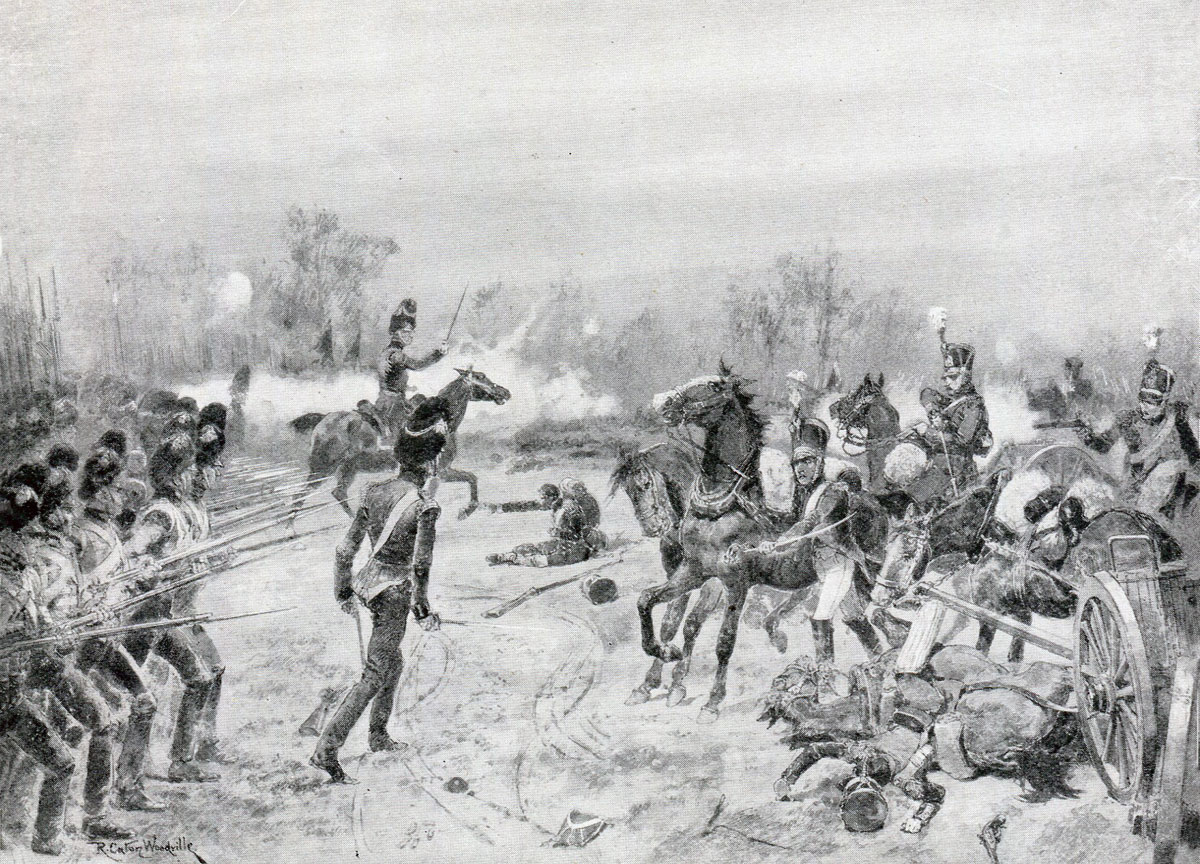

Attack of the British Fourth Division at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

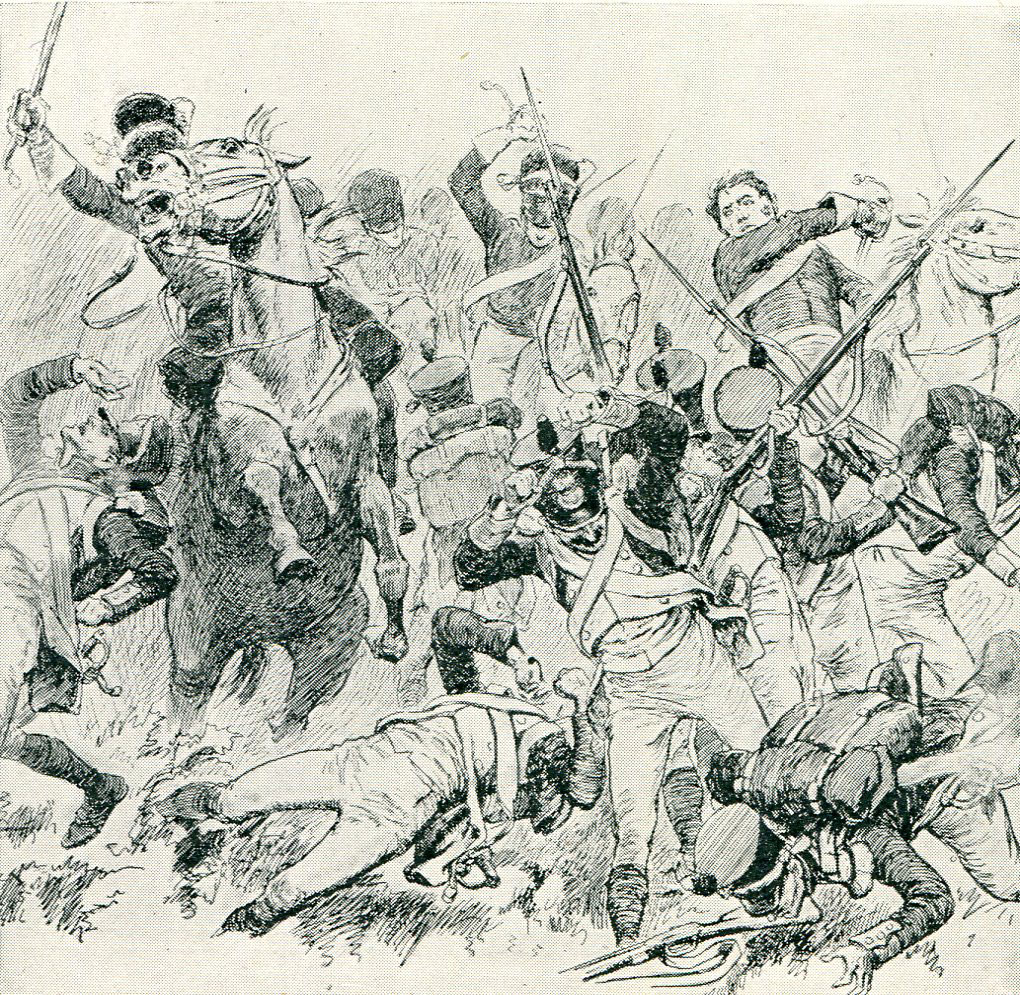

The Charge of Le Marchant’s Heavy Cavalry Brigade:

Wallace’s Brigade of Packenham’s Third Division, in pursuing Thomières’ troops, found itself confronted by an unbroken French brigade, whilst simultaneously threatened in the flank by Curto’s French Light Cavalry.

Pakenham and Wallace encouraged their battalions to form square, but the gorse was on fire and clouds of smoke engulfed the area, hampering the efforts of the officers.

At this point, the thunder of hooves was heard in the brigade’s left rear. The smoke rolled away, revealing Le Marchant’s British Heavy Cavalry Brigade, headed by General Cotton, advancing to assist the threatened infantry.

Charge of the 5th Dragoon Guards of Le Marchant’s Brigade at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Passing through Leith’s Division, Cotton led his dragoons into an attack on the French 66th of the Line, catching them before they could form square. The French regiment was dispersed, the prisoners being taken by Wallace’s infantry.

Le Marchant attacked the next French regiment, the 15th of the Line. While given more opportunity to prepare for the cavalry attack, after one volley the 15th was overrun in the same way.

Charge of Le Marchant’s British Heavy Cavalry Brigade during the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

The next regiment was the 22nd of the Line, the leading regiment of Brennier’s Division. Although not in square, the 22nd met the British dragoons with a controlled volley, but this was insufficient to halt their charge and the 22nd were also overwhelmed, many of the French infantrymen taking refuge in the British infantry lines, while those that escaped ran for the forest that lay in the French rear.

During this attack, the brigade commander, General Gaspard Le Marchant was killed.

Death of General Gaspard le Marchant at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

When the exhaustion of their horses forced the dragoons to halt, the light cavalry brigades of Anson, Arentschild and D’Urban took over.

The battle had, to this point, taken less than an hour and the French divisions of Thomières (Seventh) and Maucune (Fifth) were destroyed and that of Clausel (Second) badly damaged.

The British divisions, the Third and Fifth and the British and Portuguese cavalry re-organised, preparatory to sweeping to the east and attacking the remaining French formations.

Simultaneous with Leith’s attack, Wellington committed Cole’s Fourth Division on Leith’s left, to attack Clausel’s Division.

The Fusilier Brigade (7th Royal Fusiliers, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers and 48th Regiment) and Stubbs’ Portuguese Brigade marched through the village of Los Arapiles under a heavy French artillery bombardment and advanced on Clausel’s Division, drawn up to the right of Maucune’s Division.

Lord Wellington at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: picture by John Augustus Atkinson

After pushing back the French 122nd Regiment, stationed on the open ground between the Greater Arapil and the Monte de Azan, Cole detached the 7th Caçadores to hold back the 122nd, while his division pressed on against Clausel.

During this attack, Cole’s men suffered heavily from the French artillery on the Greater Arapil.

In conjunction with Cole’s advance, Pack’s Portuguese Brigade was directed to storm the Greater Arapil, to neutralise the French guns firing from the hill top into Cole’s left flank.

Pack’s assault on the Greater Arapil failed and the brigade was driven back off the hill with heavy losses.

The attack by Cole’s Fourth Division on Clausel began to falter, Cole himself wounded.

Three of Bonnet’s infantry regiments emerged from behind the Greater Arapil and advanced on Cole’s left flank, in spite of the gallant efforts of the 7th Caçadores to hold them back.

Advance of the Fusiliers of the British Fourth Division at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Carabinier of French 31st Light Regiment: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War

Clausel rallied his wavering first line, reinforced by his second line and attacked Cole’s two brigades, driving them back down the slope.

Officer of French 31st Light Regiment: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War

With Bonnet’s regiments on his right and supported by Ferey’s Division and Boyer’s Dragoons, Clausel advanced after Cole’s beaten Fourth Division.

Wellington’s centre was under severe threat.

Boyer’s Dragoons attacked Stubbs’ Portuguese Brigade and were driven off with difficulty, going on to charge the 53rd Regiment on the left flank of the British Sixth Division, advancing in support of the retreating Fourth Division.

However, the situation for the British and Portuguese in Wellington’s centre was about to be retrieved.

General Beresford led Spry’s Portuguese Brigade from the second line of Leith’s Fifth Division in an attack on Clausel’s left flank, bringing Clausel’s advance to a halt, Beresford himself being wounded.

Clinton’s Sixth Division came up behind Cole’s retreating men and, after an exchange of volleys, drove Bonnet’s battalions back behind the Greater Arapil.

French infantry attacked by British infantry at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: picture by Richard Simkin

With the retreat of Bonnet’s battalions on its right and attacked by Beresford on its left, Clausel’s Division was compelled to fall back.

Wellington now directed Campbell to advance into the gap between the Calvarassa de Arriba plateau and the Greater Arapil, to cut Foy’s Division off from the rest of the French army.

General of Division Claude François Ferey killed at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

Campbell failed to comply fully with this order, sending only his King’s German Legion sharpshooters.

The French 120th Regiment fell back on its parent division, Bonnet’s, in the face of the KGL skirmishers’ fire and the retreat of Clausel’s Division.

Clausel’s vigorous counter-attack against Cole’s Fourth Division had been decisively beaten back.

General Sarrut, now in command of the French left wing on the plateau of Monte de Azun, worked to save the remnants of the divisions of Thomières, Maucune and Brennier, but was relentlessly pressed back by the British Third and Fifth Divisions, supported by the Seventh Division and the Portuguese cavalry, while the cavalry brigades of D’Urban, Arentschild and Anson attacked Sarrut around his left flank.

Only two French divisions remained in reasonable fighting order, Foy’s and Ferey’s.

Foy was fully engaged holding the Calvarassa de Arriba plateau against the British Light and First Divisions.

Clausel positioned Ferey’s Division on ground to the south-east of the Greater Arapil, facing west. Ferey’s instructions from Clausel were to hold his line at all costs, to save the French army.

Ferey formed his nine battalions in line, with a battalion in square at each end of the line.

Clinton’s Sixth Division, after driving off Bonnet’s Division, advanced up the slope to attack Ferey.

Medal issued in London commemorating the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

The British Fusilier Brigade covered Clinton’s left.

At 600 yards, Clinton’s men were met with a storm of musketry and artillery grape shot, but pressed on, returning volleys at Ferey’s line.

This fight continued for an hour, the fading light augmented by the grass fires started by burning musket and cannon wads in the hot, dry weather, but obscured by the billowing smoke.

Finally, Ferey was forced to withdraw to the edge of the forest in his rear, covered by the intrepid battalions in square at each end of his line.

British guns came up and opened fire from the north flank of Ferey’s new position, raking his line, while Clinton ordered Rezonde’s Portuguese Brigade to take over the attack from his exhausted British battalions.

Ferey was killed by an artillery round, but his men repulsed the Portuguese attack.

The British battalions of the Sixth Division prepared to resume the assault, but at this point Leith’s Fifth Division came up on Ferey’s left flank.

British troops escorting French prisoners into the City of Salamanca after the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

The left regiment of Ferey’s Division, the 70th, broke under Leith’s attack, followed by the 26th and 77th of the Line, the French soldiers retreating into the forest.

The French 31st Light remained firm, covering their comrades escape, before they too retired and Ferey’s Division left the battlefield.

It was reported that there was chaos in the forest, with soldiers of all arms, supply carts and artillery intermingled.

General of Division Maximilien Sébastien Foy: Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: portrait by Horace Vernet

Clausel was wounded and taken to Alba for treatment.

It is reported that the only French infantry regiment of the divisions of the Centre and Left Wing that retained its discipline was the 31st Light.

Foy’s Division, ordered by Clausel to cover the retreat of the rest of the French Army, fell back before the British First and Light Divisions, Foy using every feature of the country to delay his attackers with what Fortescue describes as ‘consummate skill’.

Under cover of a feint counter-attack, Foy turned to the south-east and crossed the River Tormes at Alba, leaving Wellington with the belief that Foy was heading to cross the river at Huerta.

The First and Light Divisions continued to advance towards Huerta, while Cotton made for Alba with a force of cavalry.

On returning from Alba, the British cavalry was mistakenly fired on by Portuguese troops and Cotton severely wounded.

Arentschild’s brigade confirmed that Foy was crossing the River Tormes at Alba.

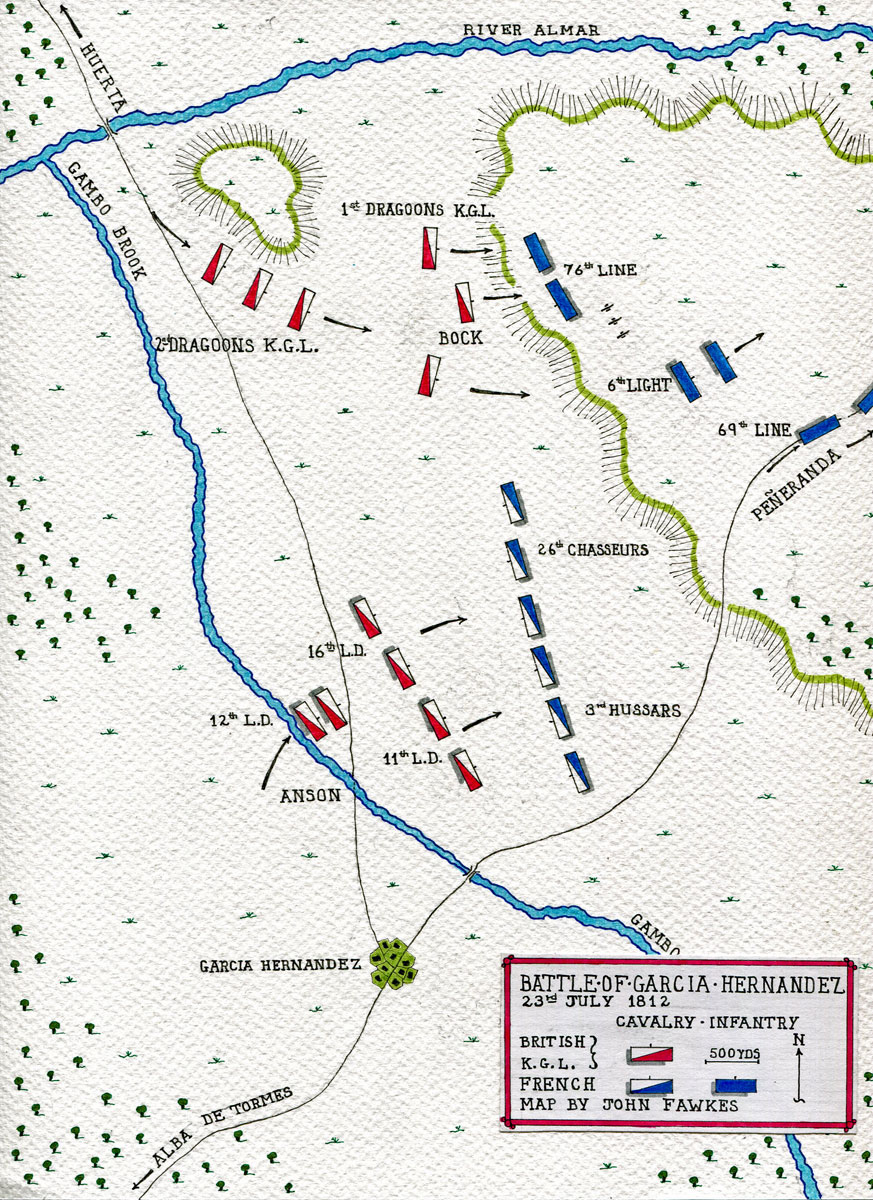

Battle of Garcia Hernandez:

At dawn on 23rd July 1812, the day after the main battle, Wellington resumed the pursuit of the beaten French army, crossing the River Tormes at Huerta with the First and Light Divisions and Bock’s Brigade of Cavalry and marching to cut the French line of retreat from Alba de Tormes, through Arevalo to Valladolid.

Anson’s Brigade of British Light Cavalry, crossing the River Tormes at Alba de Tormes, followed the French army up the Valladolid road.

Charge of the King’s German Legion Dragoons at the Battle of Garcia Hernandez on 23rd July 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Richard Knötel

The first main town on the road to Valladolid was Peñeranda. Brock’s King’s German Legion 1st and 2nd Dragoons were advancing by a difficult, stony road, when, at 2pm, they sighted French cavalry leaving the village of Garcia Hernandez, to the south of their line of march.

A French horse artillery battery unlimbered at the top of a hill to the north-east of Garcia Hernandez and began firing on the approaching German dragoons.

3 French infantry battalions formed square on the slope below the French horse artillery battery.

Seeing only the French cavalry leaving the village, Wellington ordered the cavalry to attack.

Anson’s Brigade, comprising the British 11th, 12th and 16th Light Dragoons, advancing from Garcia Fernandez across the bridge over the Gambo Brook, confronted the French 26th Chasseurs à Cheval and 3rd Hussars from Curto’s Light Cavalry Division to the right of the Valladolid road.

The British light dragoons drove back the left wing of the French cavalry.

2 French cavalry squadrons, not involved in the charge, moved along the high ground towards the French infantry formed in front of the guns.

Charge of the King’s German Legion Dragoons at the Battle of Garcia Hernandez on 23rd July 1812 in the Peninsular War: picture by Adolph Northen

The leading KGL Dragoon squadron, the First Squadron of the 1st Dragoons, with General Bock at their head, emerged from the road and immediately charged the 2 French squadrons on the slope. The French cavalry declined the action and moved away, leaving the German squadron subject to a damaging fire from the French infantry and guns on the hill.

Chevron awarded to Sergeant Thomas Cox 53rd Regiment for bravery at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War

The Third Squadron of the 1st Dragoons, coming up behind, found itself also subject to fire from the French infantry and guns on the hill. Wheeling to their left, the German dragoons attacked the nearest French infantry square, the 76th of the Line.

The German dragoon squadron received two volleys from the French infantry, before breaking into the square and virtually annihilating the battalion.

The Second Squadron of the 1st Dragoons, emerging from the road, followed the Third Squadron in turning on the French infantry. Its target was the 6th Light, now in column and hurrying up the hill to gain a more advantageous position.

The German dragoons immediately charged the French light infantry.

Captain Philippe halted the two rear companies of the 6th Light and, facing about, fired a volley into the German dragoons, causing some casualties, before the German squadron enveloped the French regiment, killing, wounding or capturing many of them.

The survivors from the various French infantry and cavalry regiments gathered at the top of the hill, where they were attacked by the Second KGL Dragoons, the other regiment of Bock’s Brigade and dispersed or captured.

Further up the road, the rear-guard of Foy’s Division formed squares and brought their artillery into action, bringing the KGL rampage to a halt.

Anson took over the chase of the retreating French army, until, on 25th July 1812, Wellington called a halt to the pursuit at Flores de Avila.

Casualties at the Battle of Salamanca: The British and Portuguese lost 5,000 killed and wounded (half of this number being casualties in the 6th and 4th Divisions). The French lost 7,000 killed and wounded and 7,000 as prisoners. The French also lost 20 guns. There were very few Spanish casualties.

The losses among the French general officers is noteworthy and in part explains the completeness of Wellington’s victory. The French commander-in-chief, Marmont, and his second-in-command, Bonnet were wounded as were Clausel and Menne. 3 French divisional commanders were killed or mortally wounded; Ferey, Thomières and Desgraviers.

Among the British general officers, Le Marchant was killed and Cotton, Leith, Cole, Beresford and Victor Alten severely wounded.

While all the French divisions were engaged in the battle and all suffered heavily, the fighting for Wellington’s army was mostly carried out by the Third, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Divisions and the cavalry brigades (not the First, Seventh and Light Divisions or the Spanish troops). In several instances the burden of the fighting by individual divisions was carried by a single brigade. Hence there was great disparity in the casualties suffered by British and Portuguese regiments.

‘Bloody 11th’ after the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

The heaviest casualties in the British contingent were in Hulse’s Brigade of the Sixth Division:

The 61st Regiment lost 24 officers and 342 soldiers killed and wounded (2/3 of its strength).

The 11th Regiment lost 16 officers and 325 soldiers killed and wounded (2/3 of its strength).

The 53rd Regiment lost 11 officers and 132 soldiers killed and wounded (1/2 of its strength).

Battle Honours and Medal for the Battle of Salamanca:

The Battle of Salamanca is a clasp on the 1848 Military General Service Medal and a battle honour for the following British regiments: 5th Dragoon Guards, 3rd and 4th Dragoons, 11th, 14th and 16th Light Dragoons, 1st Royals, 2nd Queen’s, 4th King’s Own, 5th, 7th Royal Fusiliers, 9th, 11th, 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, 27th, 30th, 32nd, 36th, 38th, 40th, 42nd Black Watch, 43rd Light Infantry, 44th, 45th, 48th, 51st, 52nd Light Infantry, 53rd, 58th, 60th Rifles, 61st, 68th, 74th, 79th Cameron Highlanders, 83rd, 88th Connaught Rangers, 94th and 95th Rifles.

Army Gold Medal:

In 1810 a Gold Medal was issued to be awarded to officers of rank of major and above for meritorious service at certain battles in the Peninsular War, with clasps for additional battles. The ‘Large Gold Medal’ was awarded to generals, the ‘Small Gold Medal’ to majors and colonels, with the medal replaced by a cross where four clasps were earned. The Battle of Salamanca was one of the battles.

Follow-up to the Battle of Salamanca:

On 12th August 1812, the British, Portuguese and Spanish army marched into Madrid. The effect of the Battle of Salamanca was to convince the British Government, finally, that the war in Spain should be continued. Wellington gained a moral ascendancy over his French opponents that he did not lose.

This aggressively conducted battle dispelled Wellington’s reputation for being a cautious general, who only fought defensive actions from positions of overwhelming strength.

Wellington’s victory reverberated through Europe. Napoleon was in increasing difficulty in Russia. Now his armies were being beaten in Spain.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Salamanca:

Lord Wellington and his staff at the Battle of Salamanca on 22nd July 1812 during the Peninsular War, also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles

- Kincaid records in ‘Adventures in the Rifle Brigade’ that before the Battle of Salamanca ‘We heard, about this time, that Marmont had just sent to his ci-devant landlord, in Salamanca, to desire that he would have the usual dinner ready for himself and staff at six o’clock; and so satisfied was “mine host” of the infallibility of the French marshal, that he absolutely set about making the necessary preparations.’

- Once Wellington’s troop dispositions were ordered, there was a period of an hour before the attack could begin. Wellington ordered his military secretary, Lord Fitzroy Somerset, to wake him when the head of the French column reached a particular stone. Wellington then fell asleep.

- When Wellington briefed General Pakenham on the attack to be made by the 3rd Division on the head of the French column, he ended by saying ‘Do you see those fellows on the hill, Pakenham? Throw your division into columns; at them directly and drive them to the devil…’ Pakenham saluted and asked to shake Wellington’s hand, saying ‘Let me shake the hand of a conqueror.’ Wellington was married to Pakenham’s sister, Kitty.

- As a reward for the victory, Lord Wellington was given a step up in the peerage. His reaction was to say ‘What the devil’s the use of making me a marquis?’

- Fortescue comments that every initiative by the British in the battle was triggered by Wellington in person. Wellington was not prepared to entrust his instructions to an adc or an orderly, but rode to each subordinate commander and gave him his orders in person, in several instances remaining to ensure they were carried out correctly. Fortescue makes the point that while this limited Wellington’s ability to monitor all that was going on across a wide battlefield, it enabled Wellington to ensure that each general received the correct instructions and fully understood what was required of him.

- Major General Gaspard Le Marchant, killed at the Battle of Salamanca commanding the 1st Brigade of British cavalry, was a major reforming figure in the British Army. Le Marchant was responsible for bringing in new training systems for the British cavalry at the end of the 18th Century, enabling them to meet the formidable French cavalry in battle on an equal footing. Le Marchant assisted in establishing the Army’s Staff College at High Wycombe and the junior branch at Marlow, before it was moved to its present location at Sandhurst. Le Marchant’s death at the Battle of Salamanca was a major loss to the British Army.

- During the charge of Wallace’s Brigade at the Battle of Salamanca, the 88th Regiment, the Connaught Rangers, captured a ‘Jingling Johnnie’ from the French 101st Regiment. The French regiment is said to have taken the instrument from the Moors in a previous engagement. The ‘Jingling Johnnie’ was carried on parade by the Connaught Rangers until their disbandment in 1922.

- The 5th Dragoon Guards were known as ‘the Green Horse’ from the colour of their cuffs and facings and their origins as one of the old Regiments of Horse, before their conversion to Dragoon Guards in the 1760s.

- The British 11th Regiment of Foot earned the nickname ‘the Bloody 11th’ due to its casualties at the Battle of Salamanca, fighting in Hulse’s Brigade of the Sixth Division.

References for the Battle of Salamanca:

See the extensive list of references given at the end of the Peninsular War Index.

The previous battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Almaraz

The next battle of the Peninsular War is the Battle of Garcia Hernandez

Podcast of the Battle of Salamanca: Wellington’s victory on 22nd July 1812 over the French army of Marshal Marmont, during the Peninsular War, leading to the re-capture of Madrid; also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

Podcast of the Battle of Salamanca: Wellington’s victory on 22nd July 1812 over the French army of Marshal Marmont, during the Peninsular War, leading to the re-capture of Madrid; also known as the Battle of Los Arapiles or Les Arapiles: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts