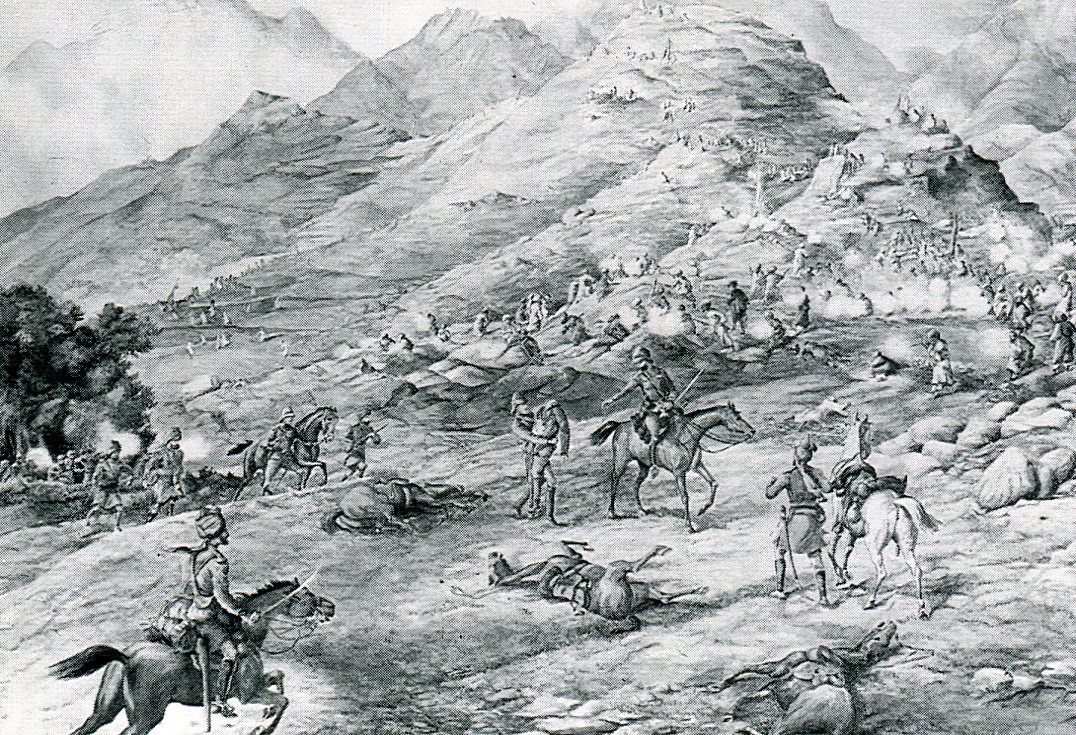

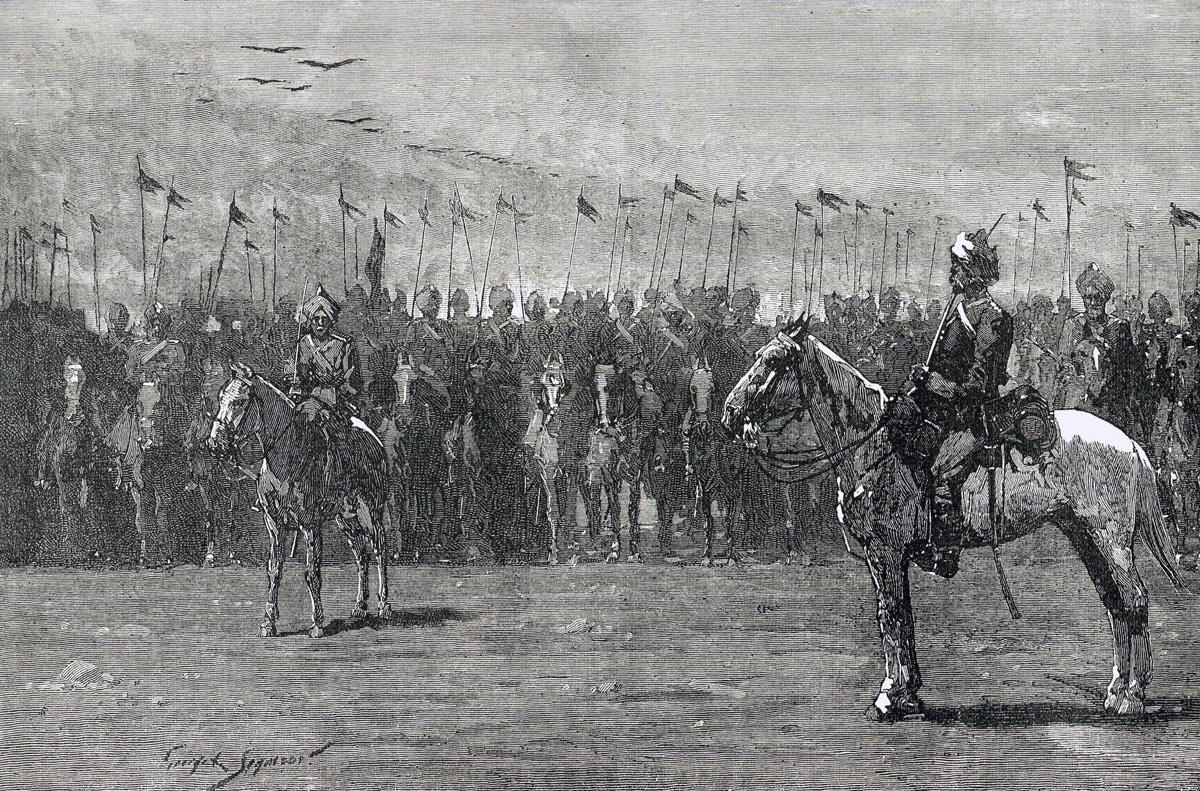

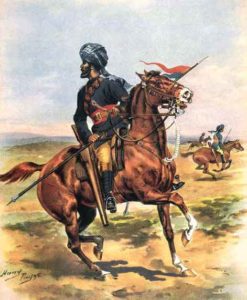

The triumph of British and Bengal light cavalry: General Lake’s defeat of the Gwalior Mahrattas on 1st November 1803, after capturing Delhi, the future capital city of British-ruled India

Podcast on the Battle of Laswaree: The triumph of British and Bengal light cavalry in General Lake’s defeat of the Gwalior Mahrattas on 1st November 1803, after capturing Delhi, the future capital city of British-ruled India: John Mackenzie’s britishbattles.com podcasts

The previous battle in the Second Mahratta War is the Battle of Assaye

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Roliça

To the Second Mahratta War index

Battle: Laswaree

War: Second Mahratta War

Date of the Battle of Laswaree: 1st November 1803

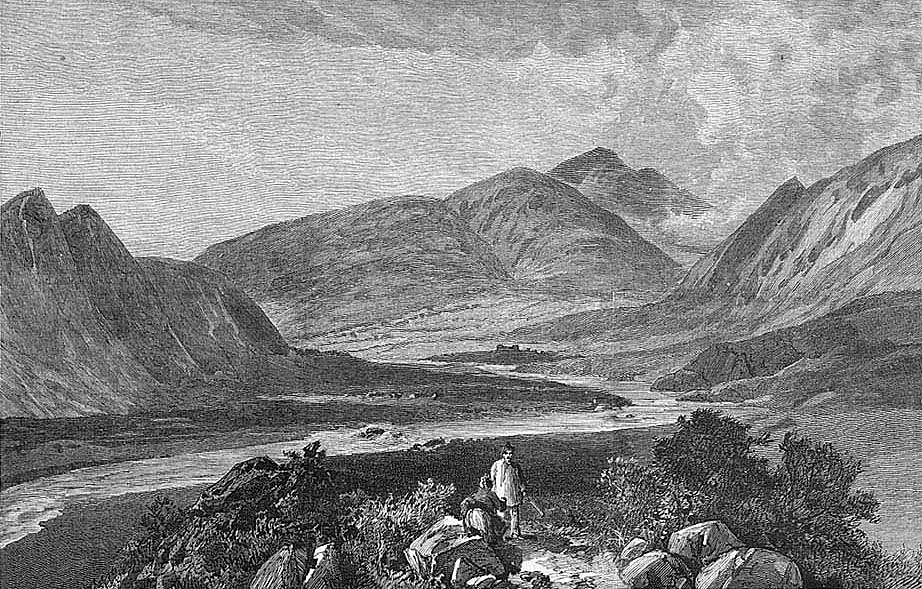

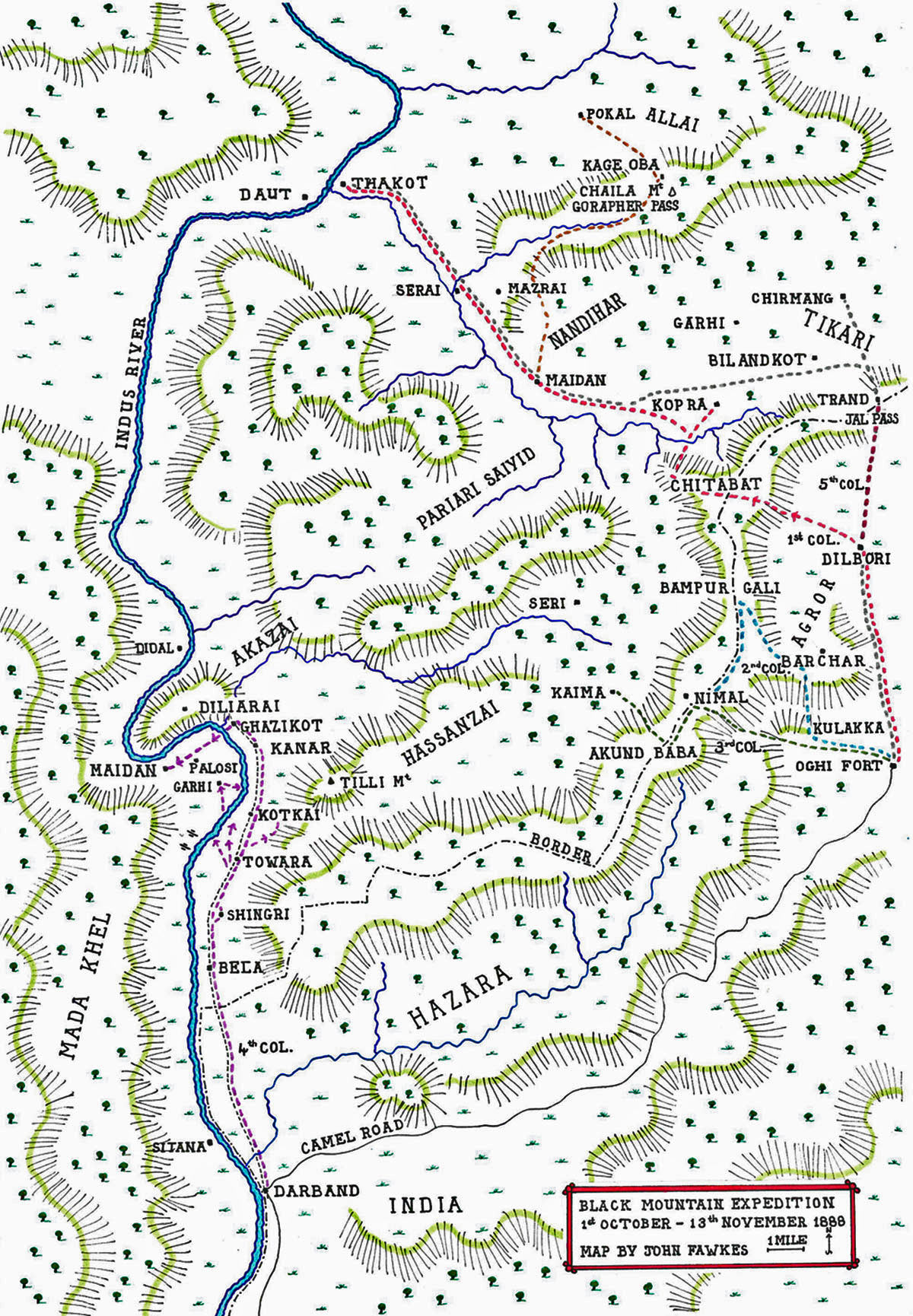

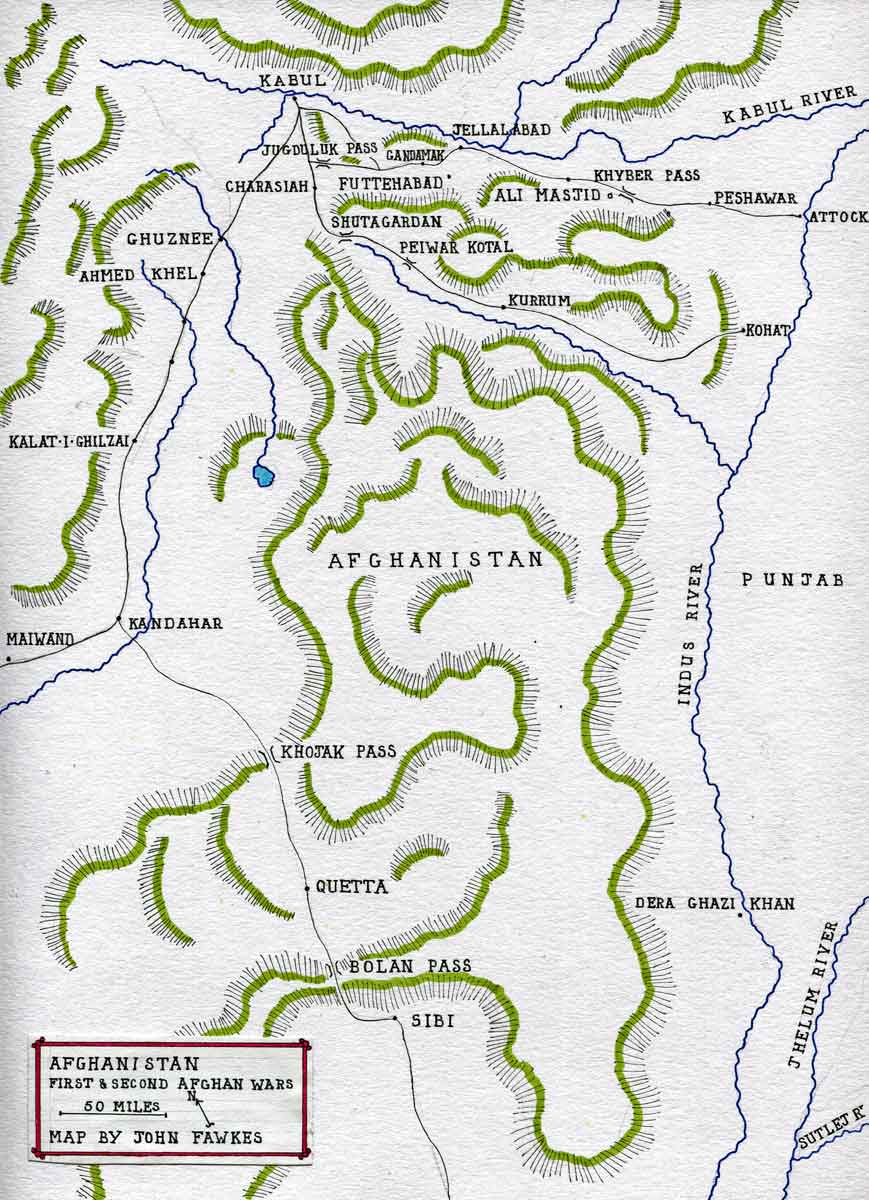

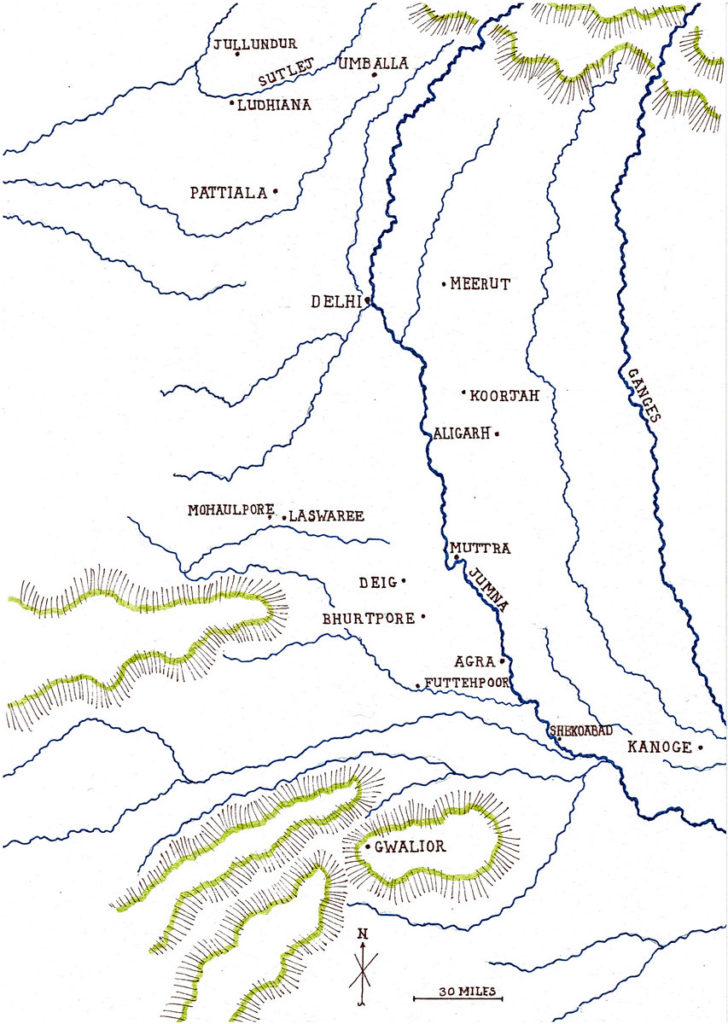

Place of the Battle of Laswaree: Northern India, 80 miles to the south-west of Delhi

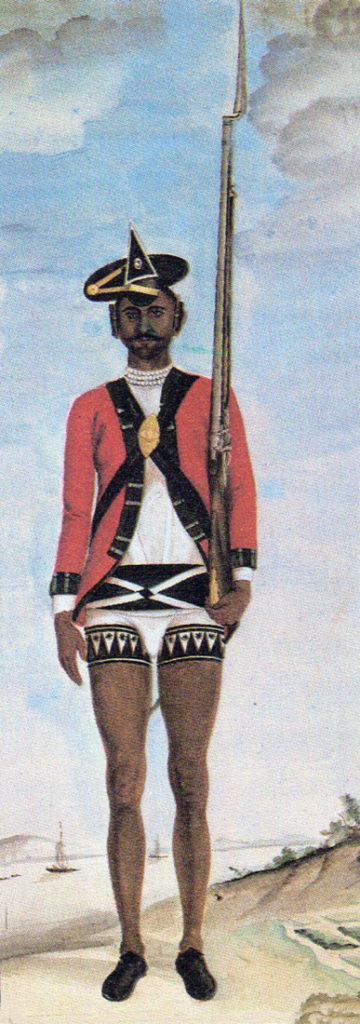

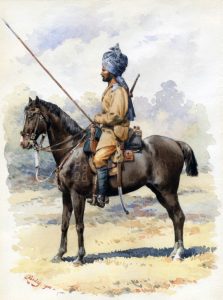

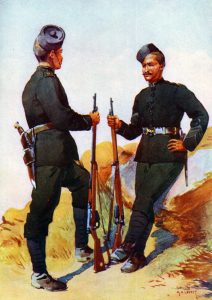

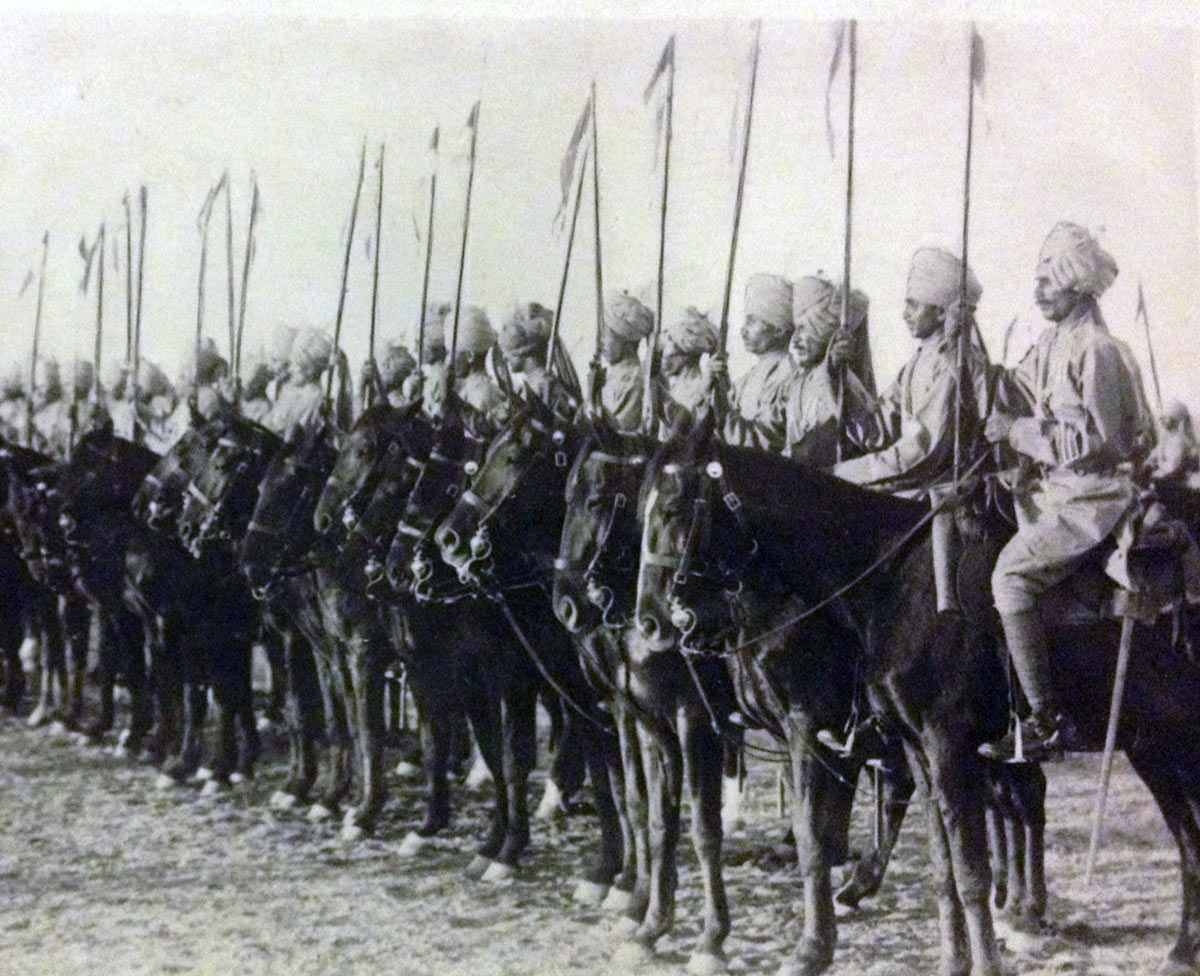

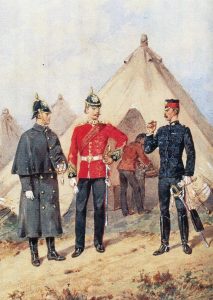

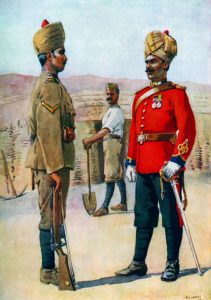

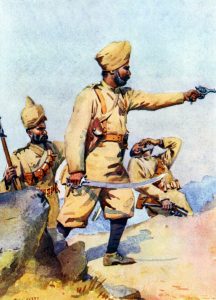

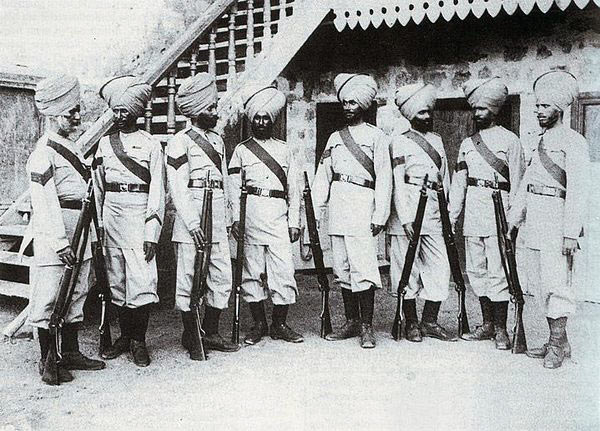

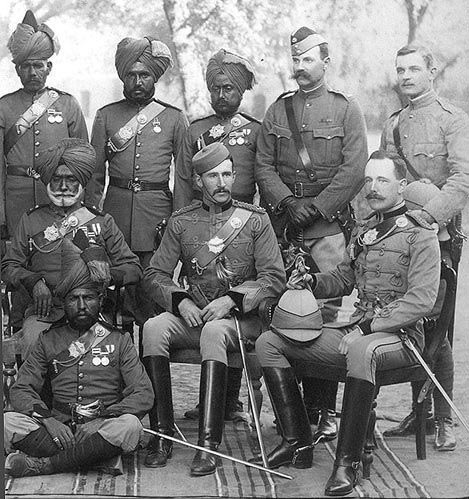

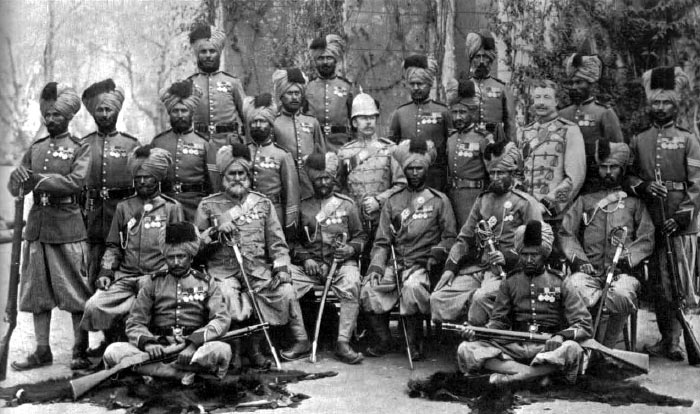

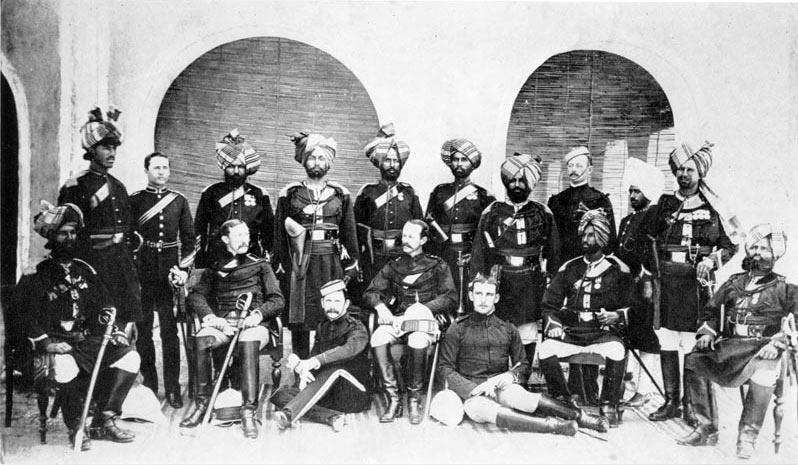

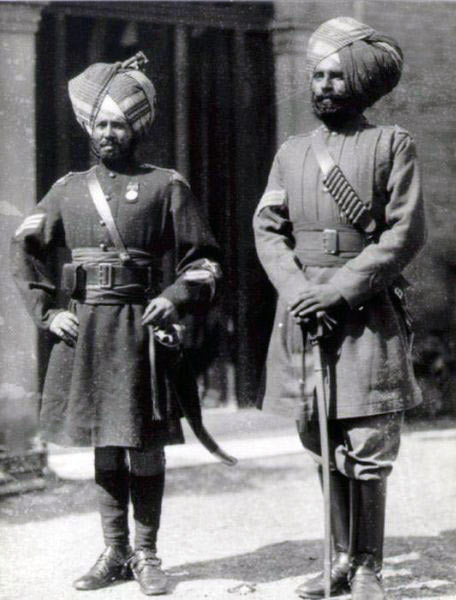

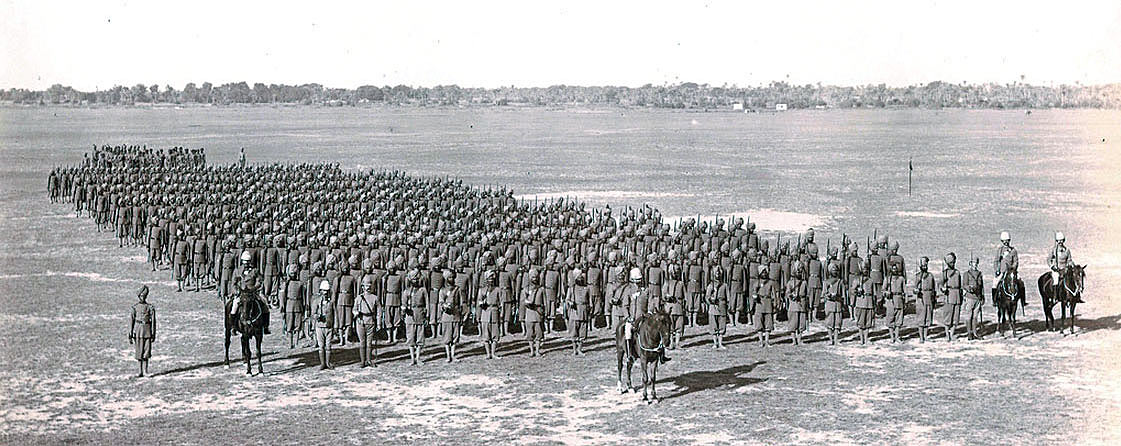

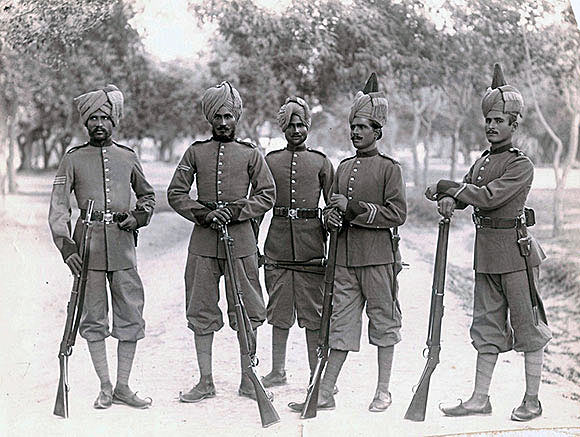

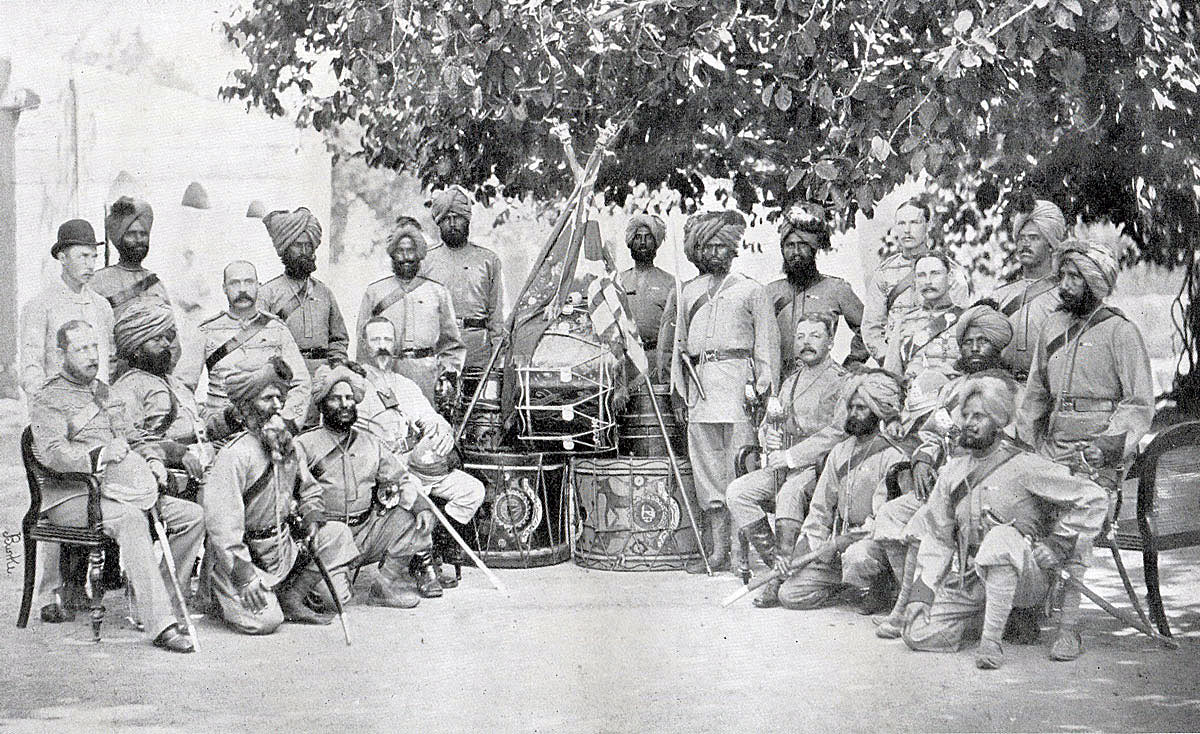

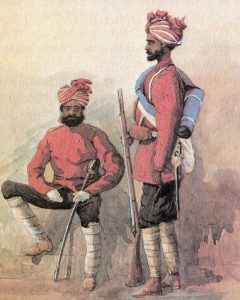

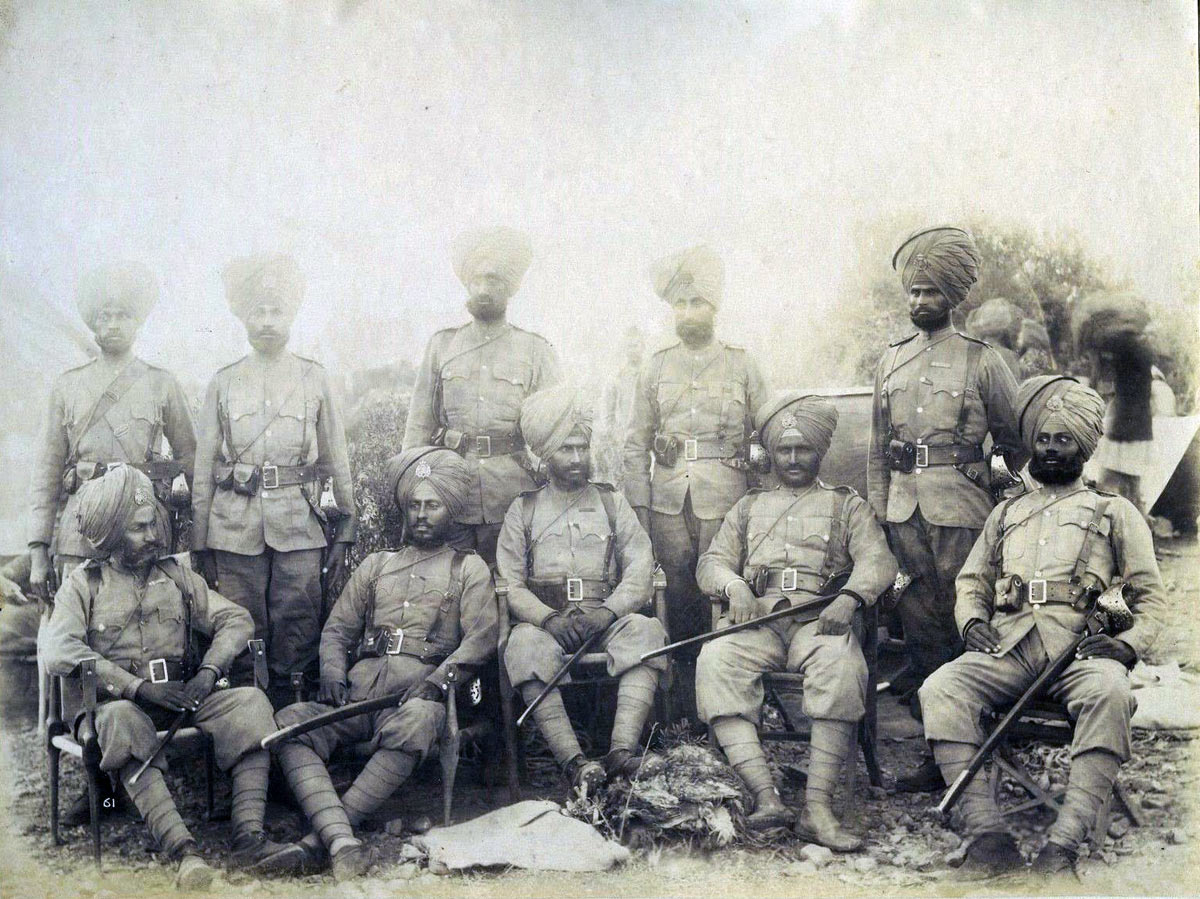

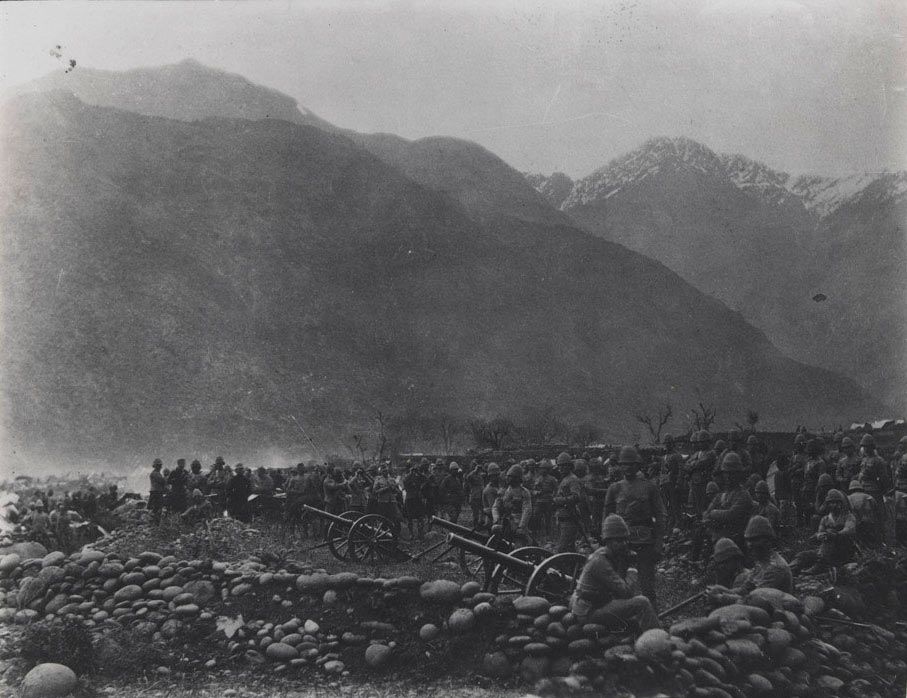

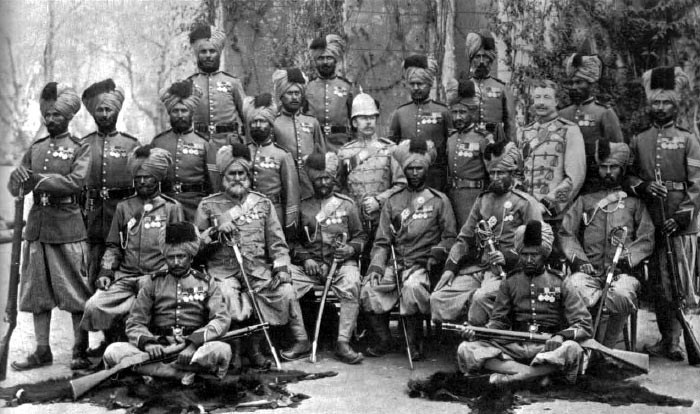

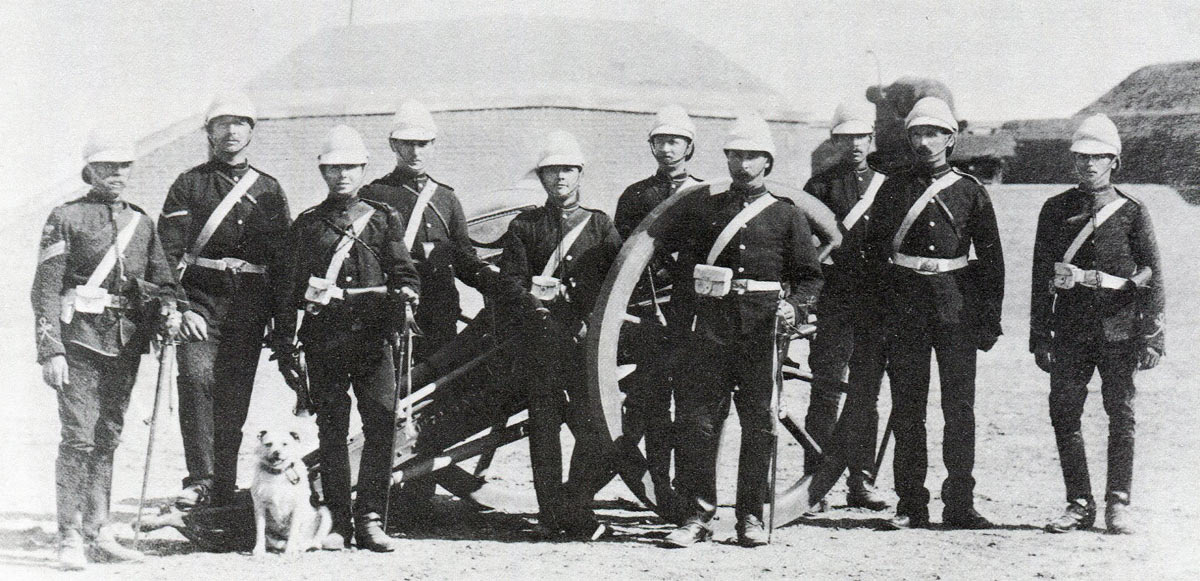

Combatants at the Battle of Laswaree: An army of British and sepoy troops from the Bengal Presidency of the East India Company against an army of the Mahratta ruler of Gwalior, Daulat Rao Scindia.

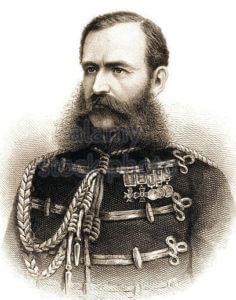

Commanders at the Battle of Laswaree: General Lake against the Mahratta general Abaji.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Laswaree: Lake’s army at the Battle of Laswaree numbered around 6,000 men.

Scindia’s Mahratta Army at the Battle of Laswaree numbered some 9,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry with 72 guns.

Winner of the Battle of Laswaree:

The British Bengal army of General Lake.

Background to the Battle of Laswaree:

In 1800, the East India Company, the British governing agency in India, occupied three areas of the sub-continent; the port of Bombay on the west coast of India; an area around Madras, stretching north and south of the city along the east coast; and the substantial presidency of Bengal, based on the trading port of Calcutta in the Hoogli delta. The three presidencies were separated by tracts of country governed by Indian potentates.

In the Deccan, the southern central area of the Indian isthmus, the British controlled the principalities of Hyderabad and Mysore in the very south.

Separating the three British presidencies, stretching from coast to coast and up to the borders of Nepal in the North and the Punjab in the West, lay the sprawling Mahratta Confederacy, combining the five principalities of the Peshwa Baji Rao, Daulat Rao Scindia, Jeswant Rao Holkar, the Bhonslar Raja of Berar and the Gaikwar of Baroda.

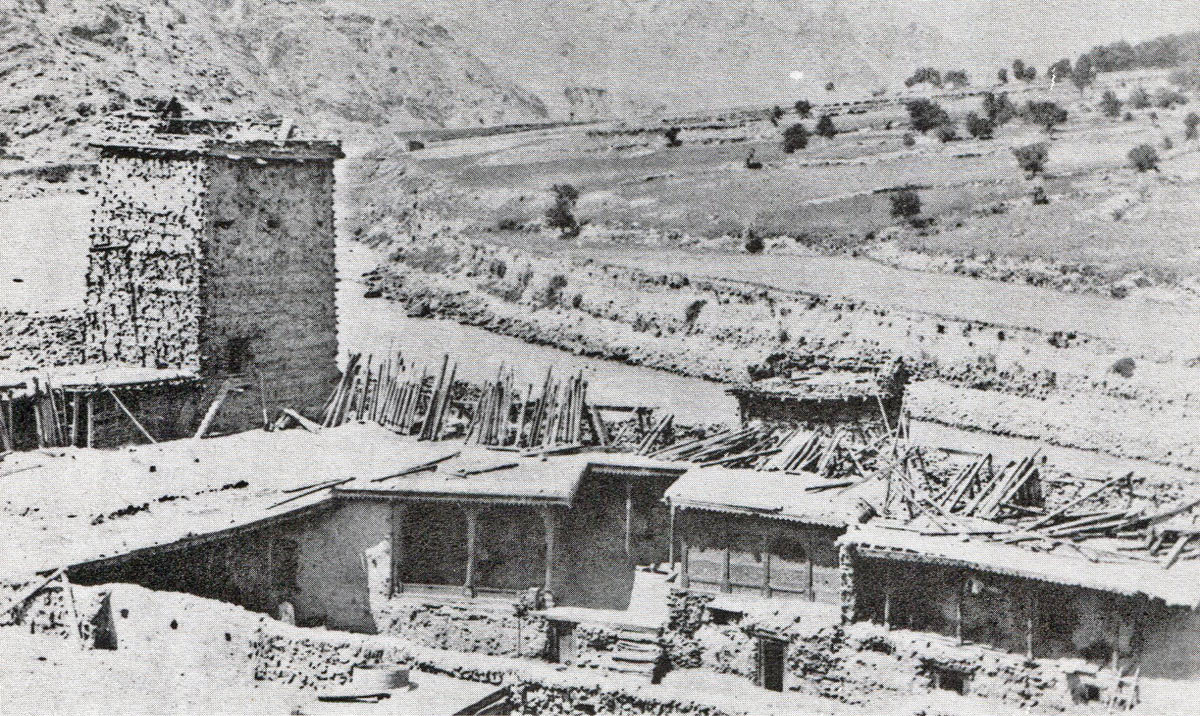

Daulat Rao Scindia was the Mahratta ruler of Gwalior. Scindia’s territory in the north included the powerful fortress of Aligarh, the city of Agra and the old Moghul capital of Delhi, each with garrisons of French trained troops.

Scindia’s interests were represented by the French officer, Colonel Perron, based in Delhi and the effective ruler of the north of Scindia’s dominion.

In 1802, war broke out within the Confederacy, with Holkar and Berar defeating the Peshwa and Scindia and driving the Peshwa from his territory to seek refuge with the East India Company.

The British Governor-General, the aggressive and resourceful Lord Mornington, seized on the pretext of re-instating the Peshwa in his capital, Poona, close to the British city of Bombay, to invade the Confederacy from Mysore in the South and from Oudh in the North.

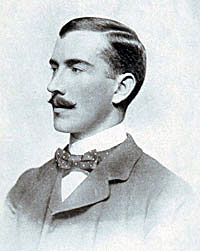

While General Arthur Wellesley led the attack to restore the Peshwar in Poona, the incursion from Oudh was to be led by General Lake.

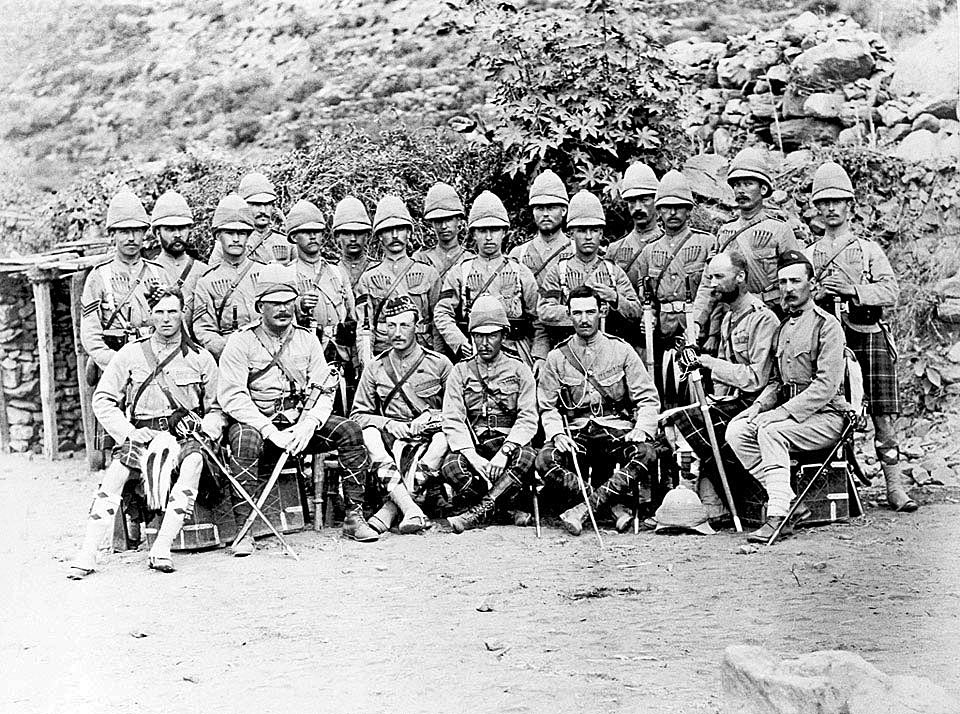

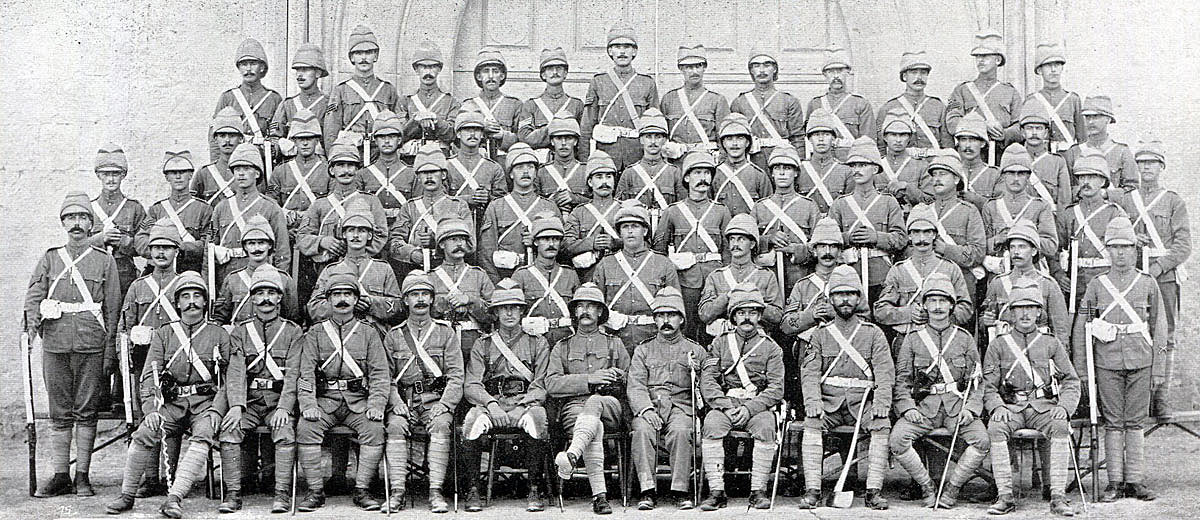

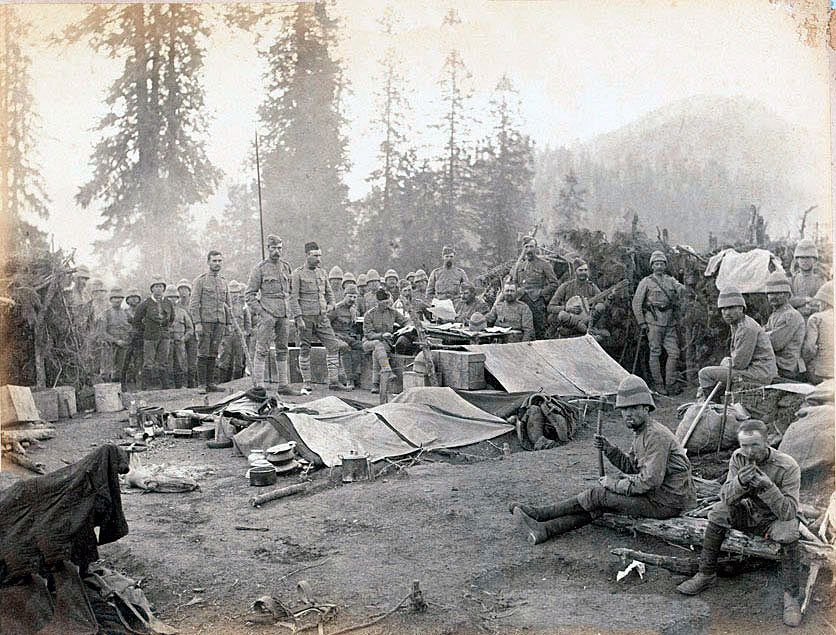

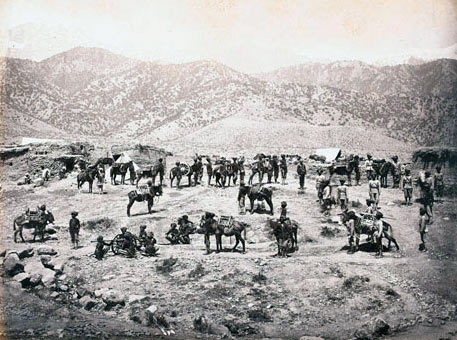

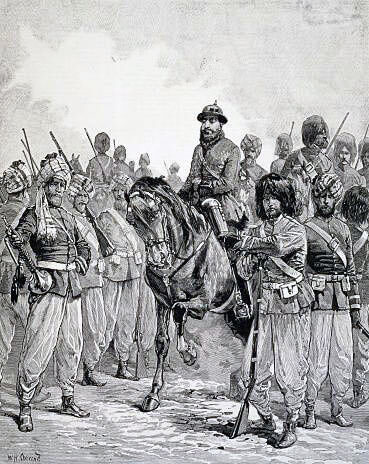

In August 1803 Lake assembled his army at Kanoge on the River Ganges, forming three cavalry brigades and four infantry brigades:

Cavalry:

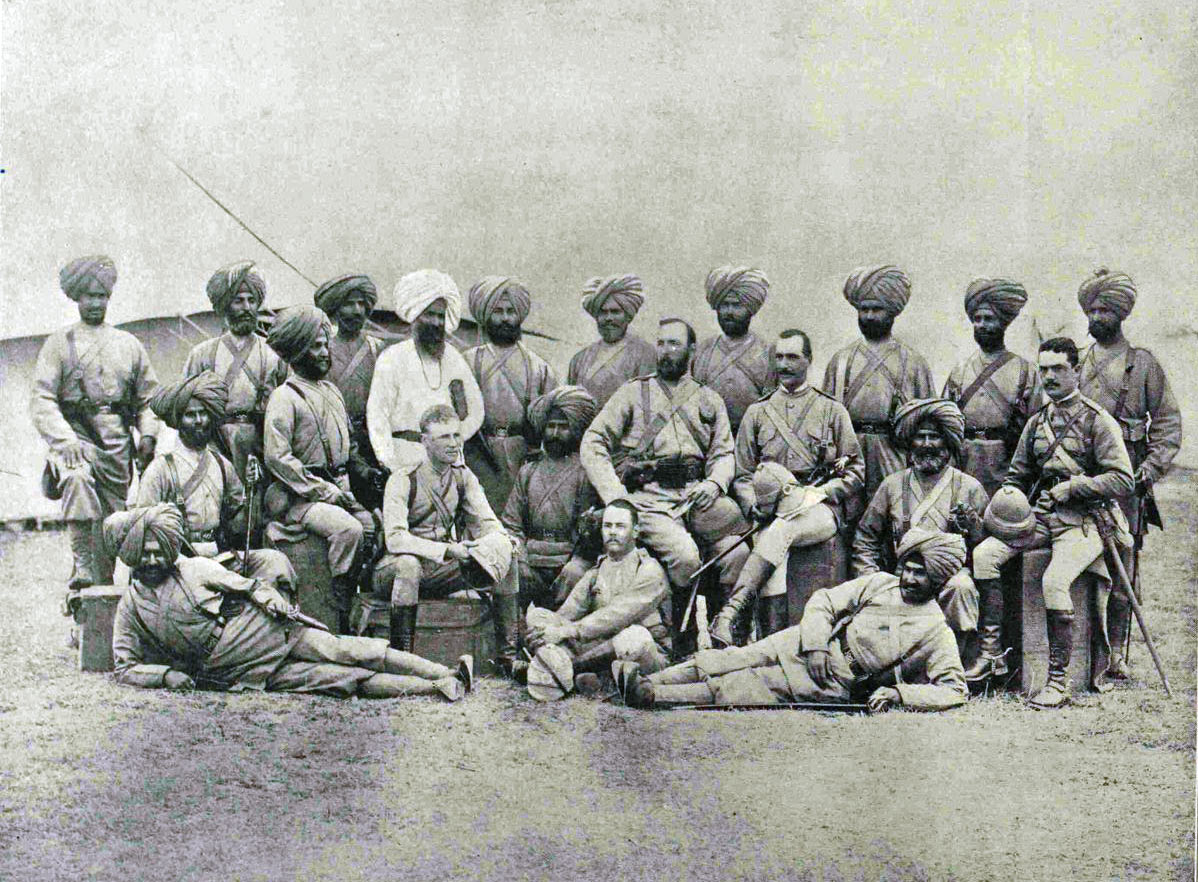

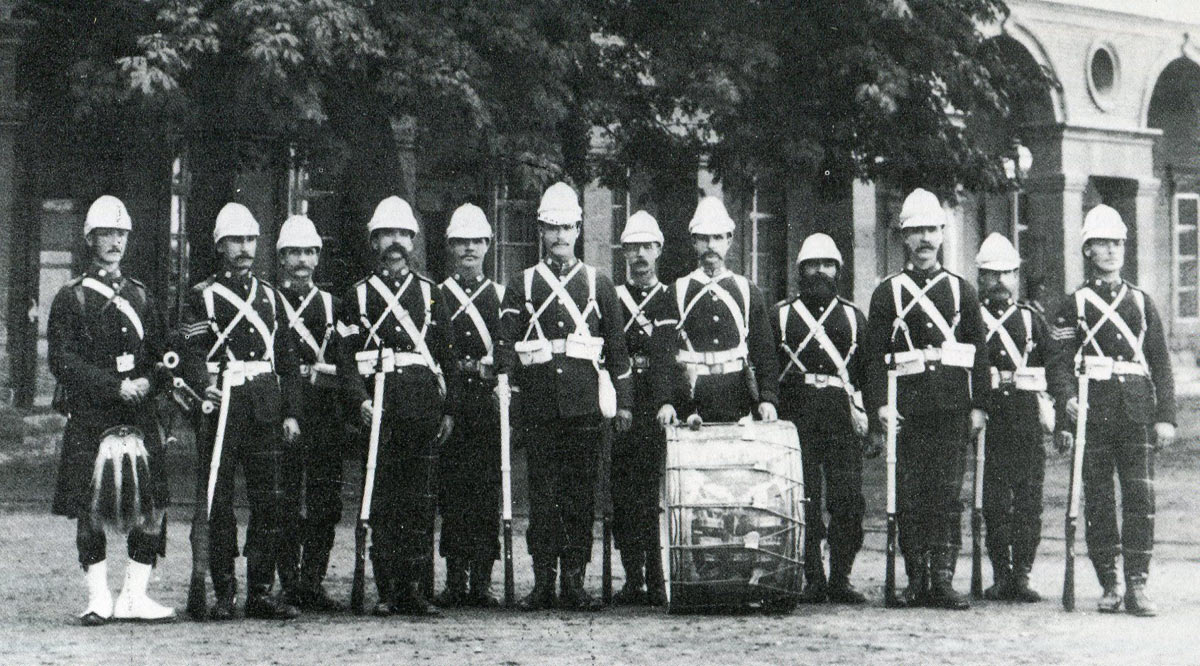

1st Brigade commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Vandeleur: HM 8th Light Dragoons, 1st and 3rd Bengal Native Cavalry

2nd Brigade commanded by Colonel St Leger: HM 27th Light Dragoons, 2nd and 6th Bengal Native Cavalry

3rd Brigade commanded by Colonel Macan: HM 29th Light Dragoons, 4th Bengal Native Cavalry

Infantry:

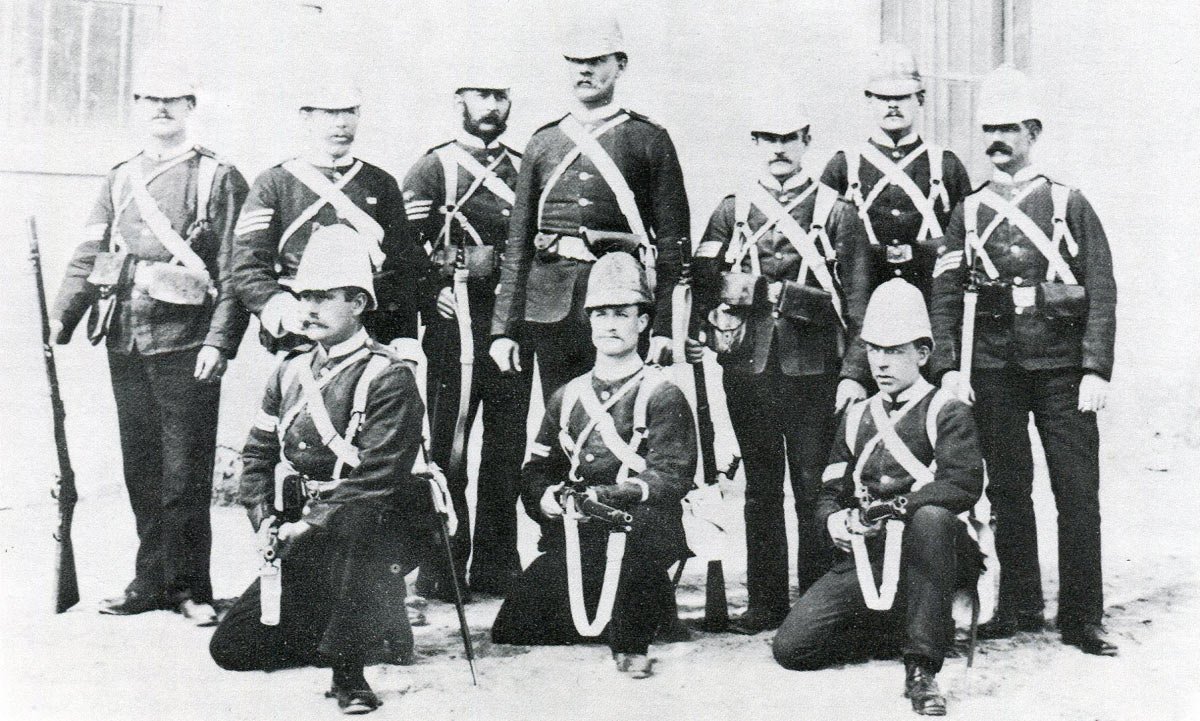

1st Brigade commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Monson: HM 76th, 1st and 2nd/4th Bengal Native Infantry, 4 Cos 17th Native Bengal Native Infantry

2nd Brigade commanded by Colonel Clarke: 2nd/8th, 2nd/9th, 1st/12th and 6 Cos 16th Bengal Native Infantry

3rd Brigade commanded by Colonel Macdonald: 2nd/12th, 1st and 2nd/15th Bengal Native Infantry

4th Brigade commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Powell: 1st and 2nd/2nd, 1st/14th Bengal Native Infantry

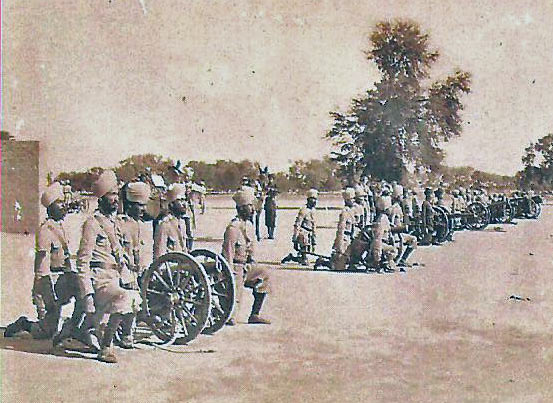

Artillery: 2 galloper guns to each cavalry regiment (16 guns), 1 battalion gun to each infantry battalion (12 guns), 1 brigade of horse artillery (6 guns), 6 six pounders, 4 twelve pounders and 3 five and a half inch howitzers. Total of 47 guns.

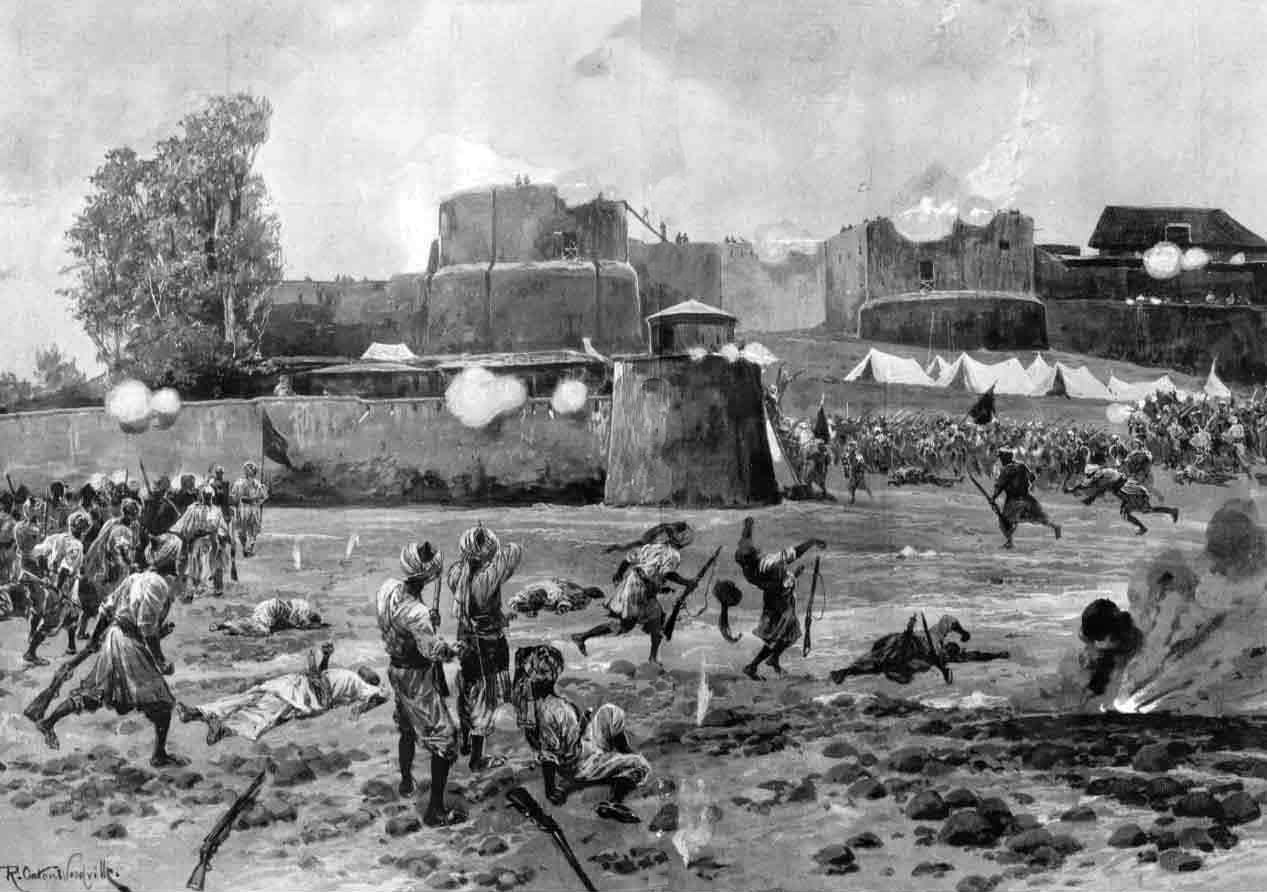

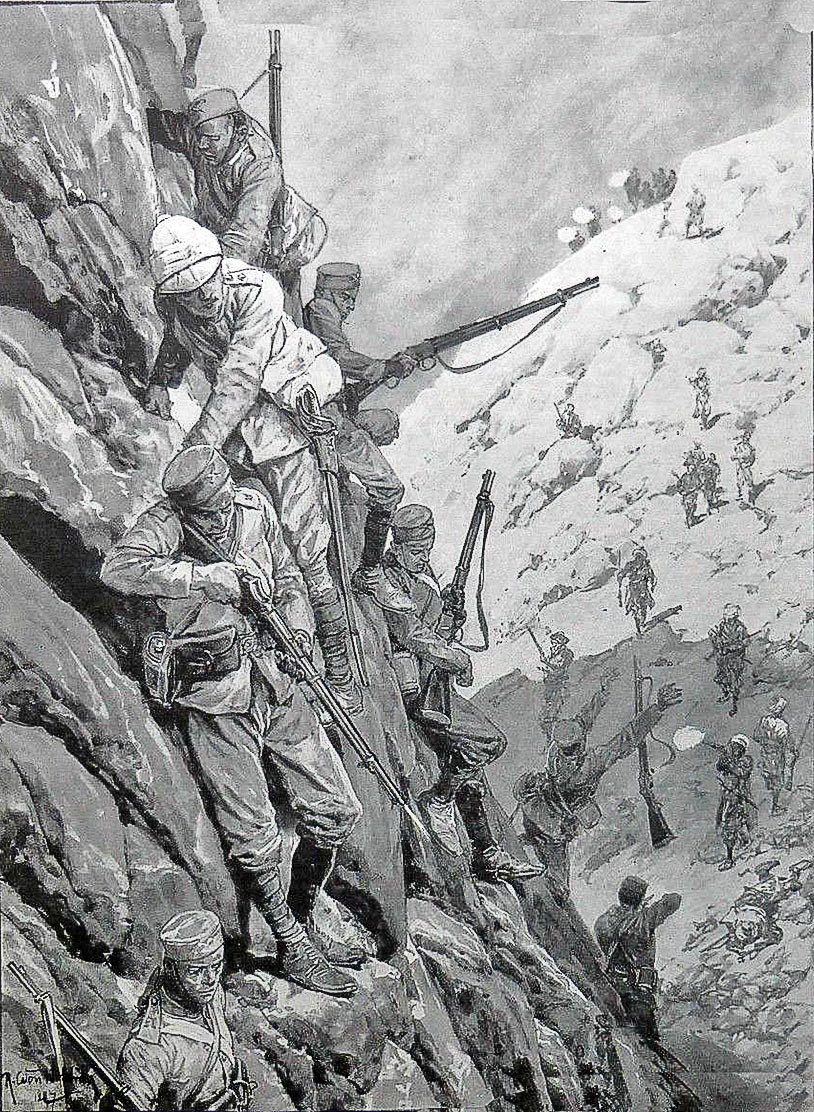

The Battle of Aligarh:

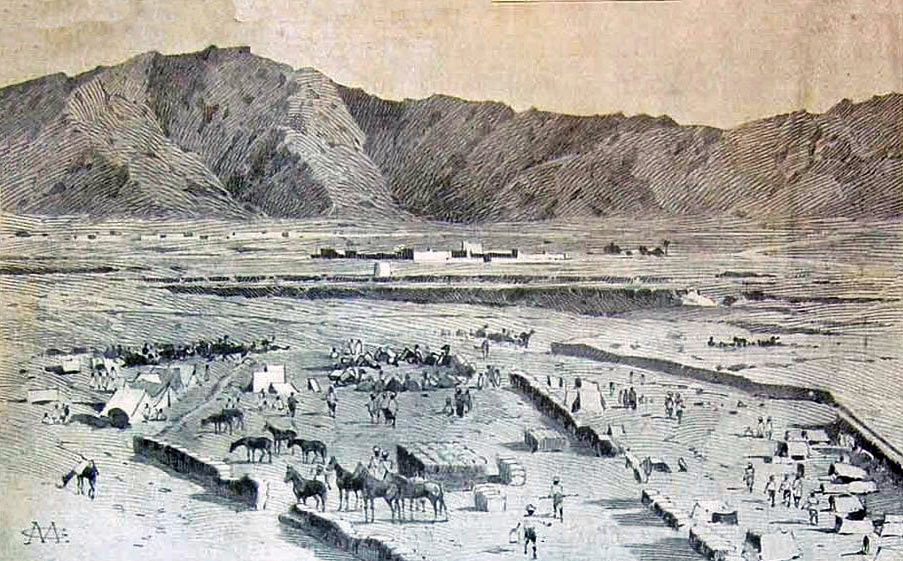

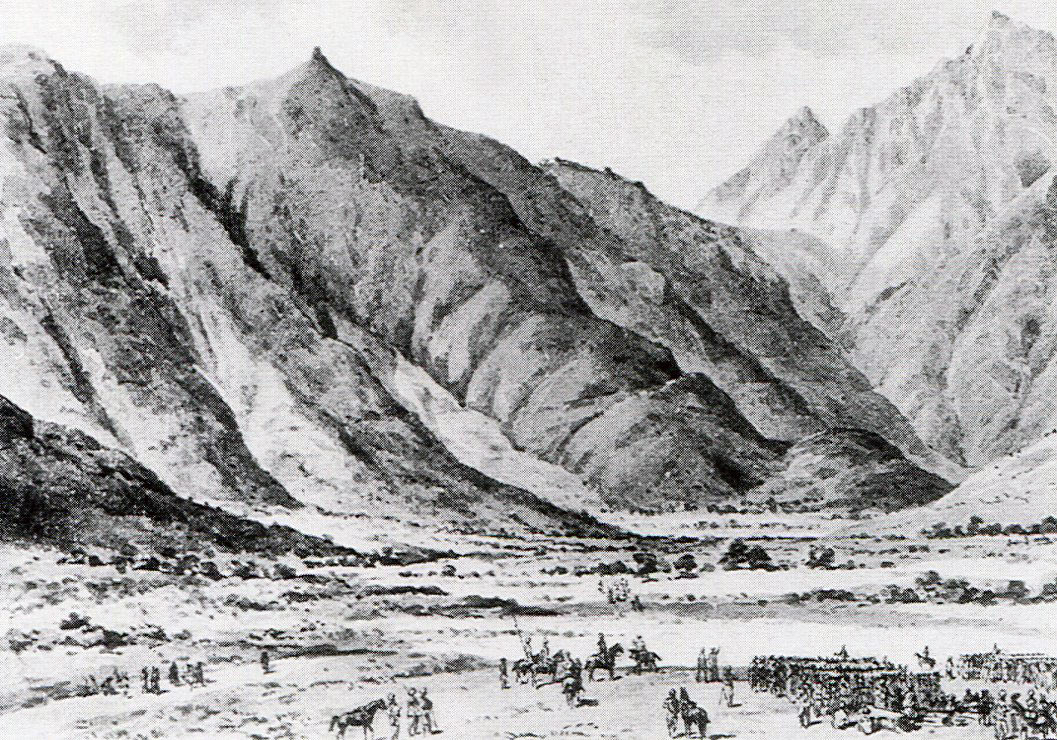

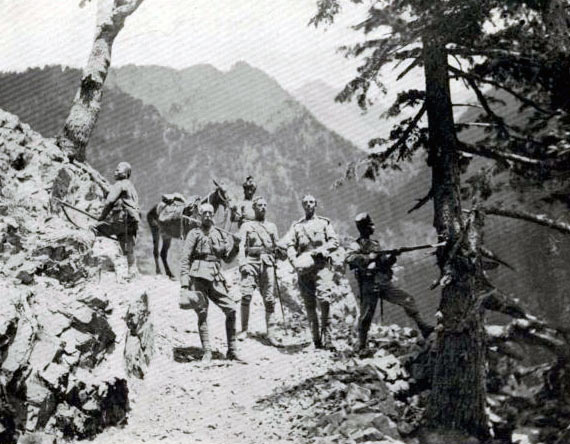

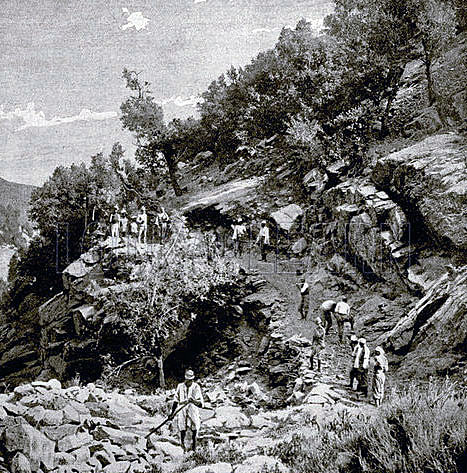

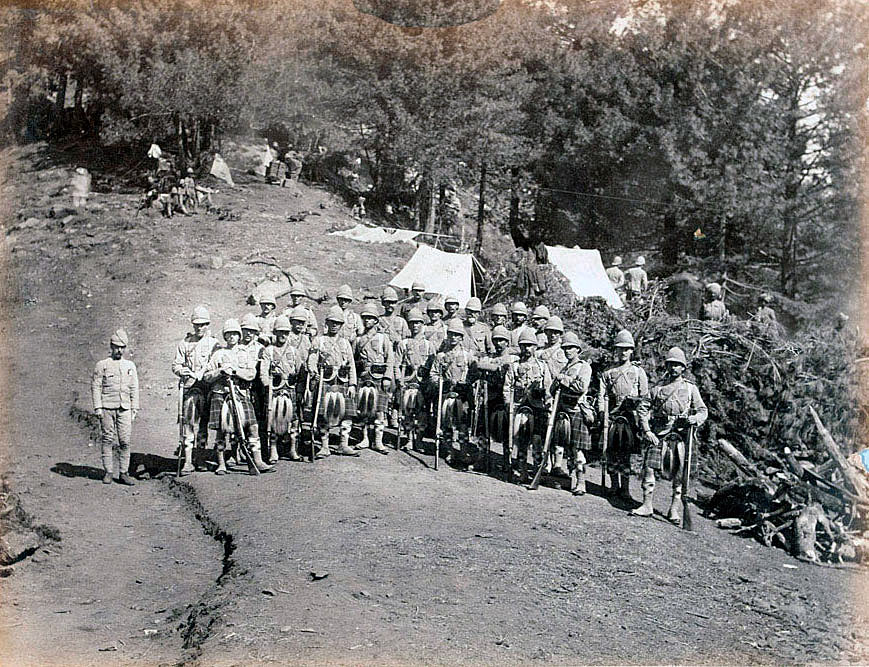

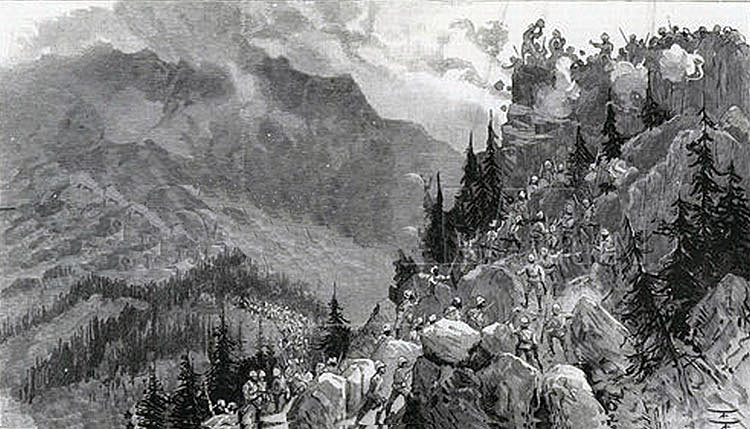

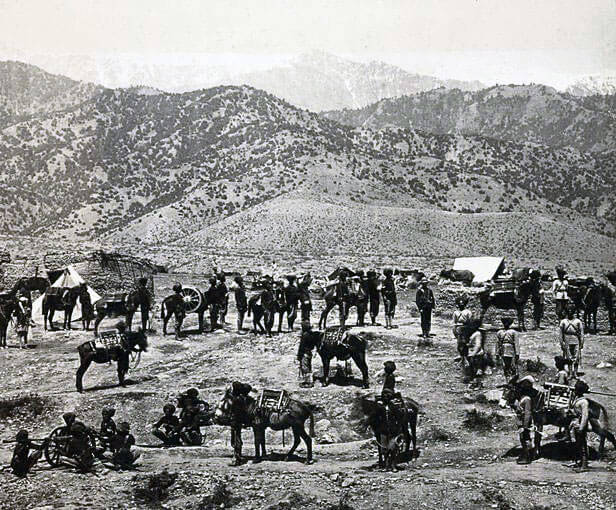

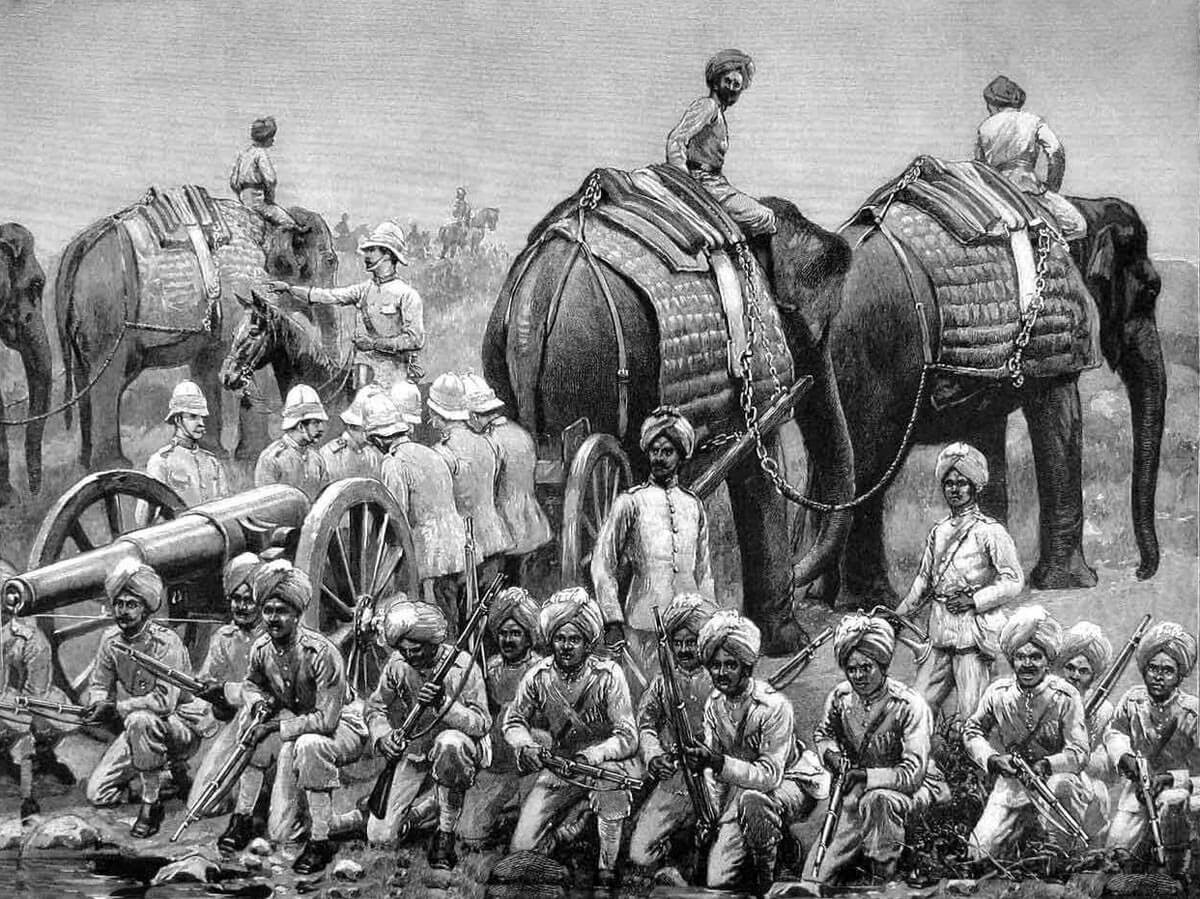

On 29th August 1803, marching in a large square and swelled by followers ten times the number of soldiers, Lake’s army entered Mahratta territory, moving towards the fortress of Aligarh, where the French general commanding Scindia’s army in his northern lands, General Perron, was encamped.

Lake’s army left its baggage and continued towards Aligarh, finding Perron’s army in the process of striking camp.

The Mahratta cavalry, numbering around 20,000 men, formed up in the plain, behind a large marshy area, with the fortress of Aligarh on their right and a village on their left.

Lake took command of his cavalry and led the three brigades off to the right, around the marshy area.

Lake’s guns played on the Mahratta cavalry, firing directly across the area of marsh and inflicting casualties, while the Mahrattas fell back before Lake’s cavalry force and finally left the field.

Perron with his bodyguard rode off to Agra, leaving his subordinate Colonel Pedron to defend Aligarh.

Lake called on Pedron to surrender, a summons that caused six of Pedron’s European officers to desert to the British.

Pedron answered Lake’s demand with an evasive response, seeking time to improve his defences.

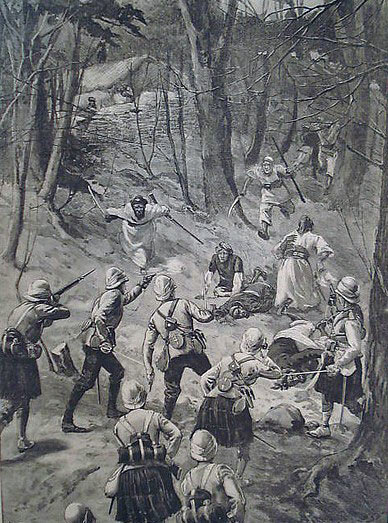

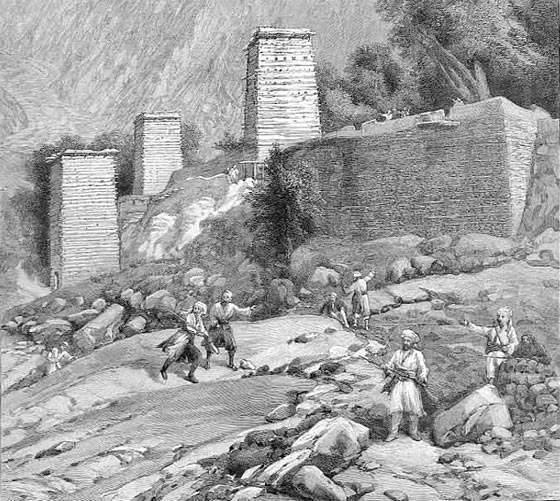

On 3rd September 1803, Lake concluded that Pedron did not intend to surrender and prepared his attack.

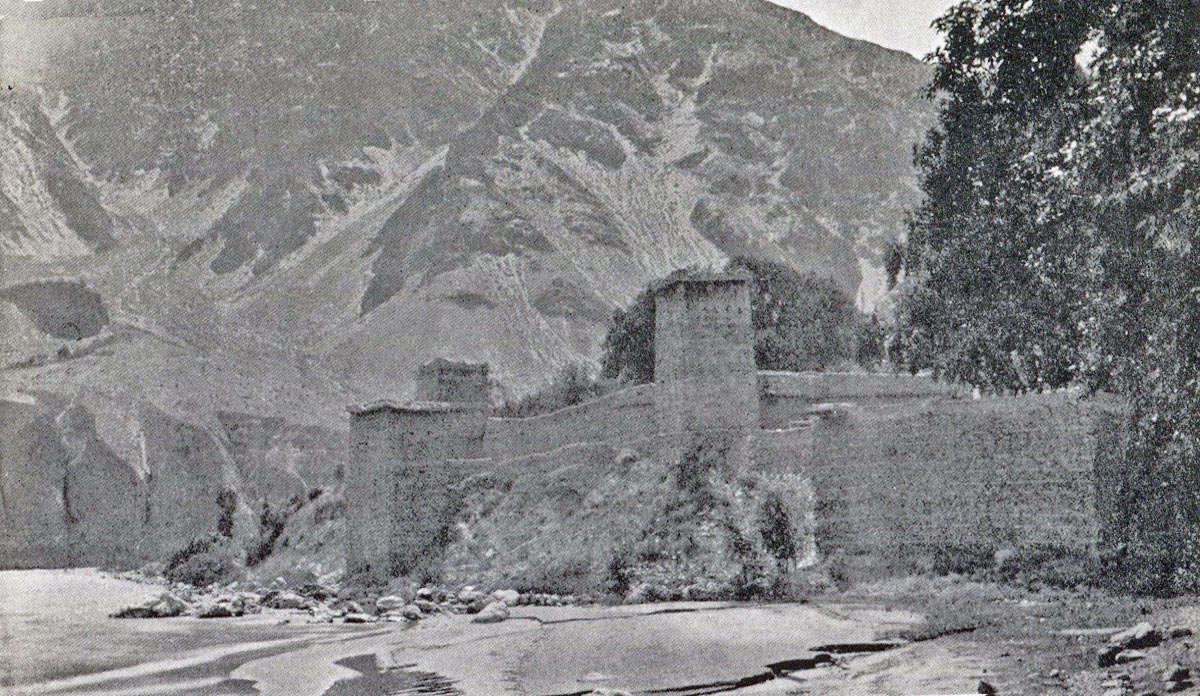

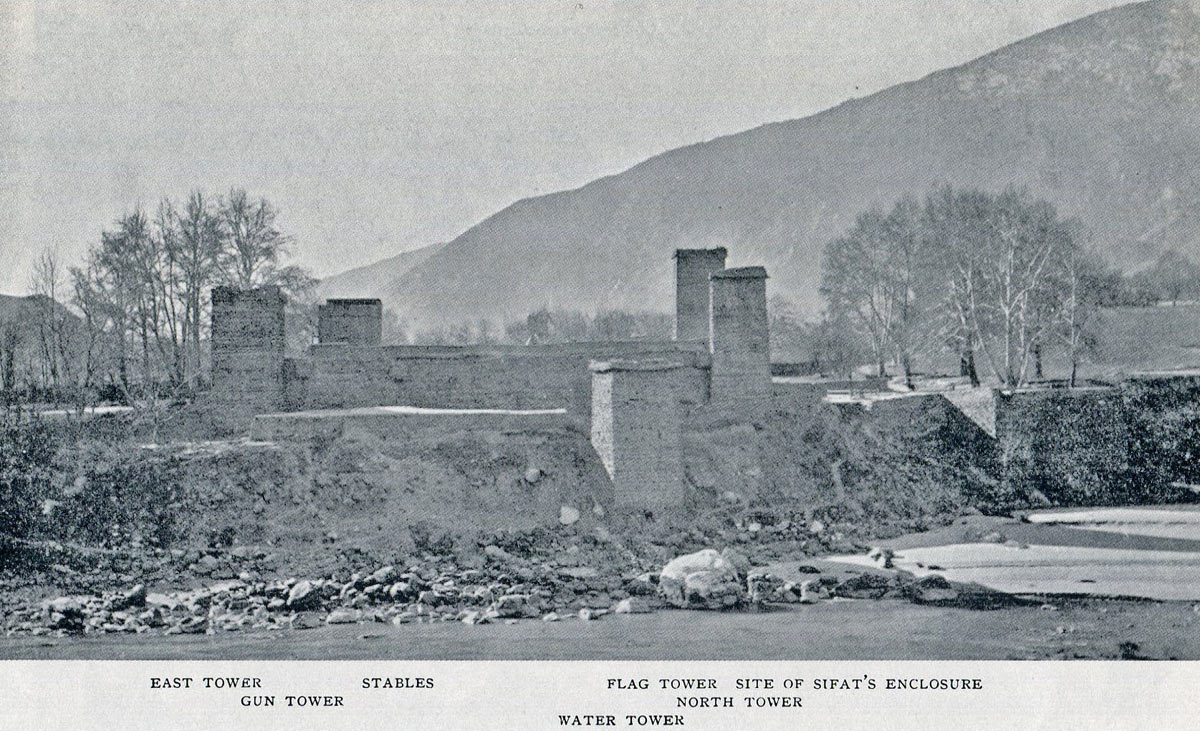

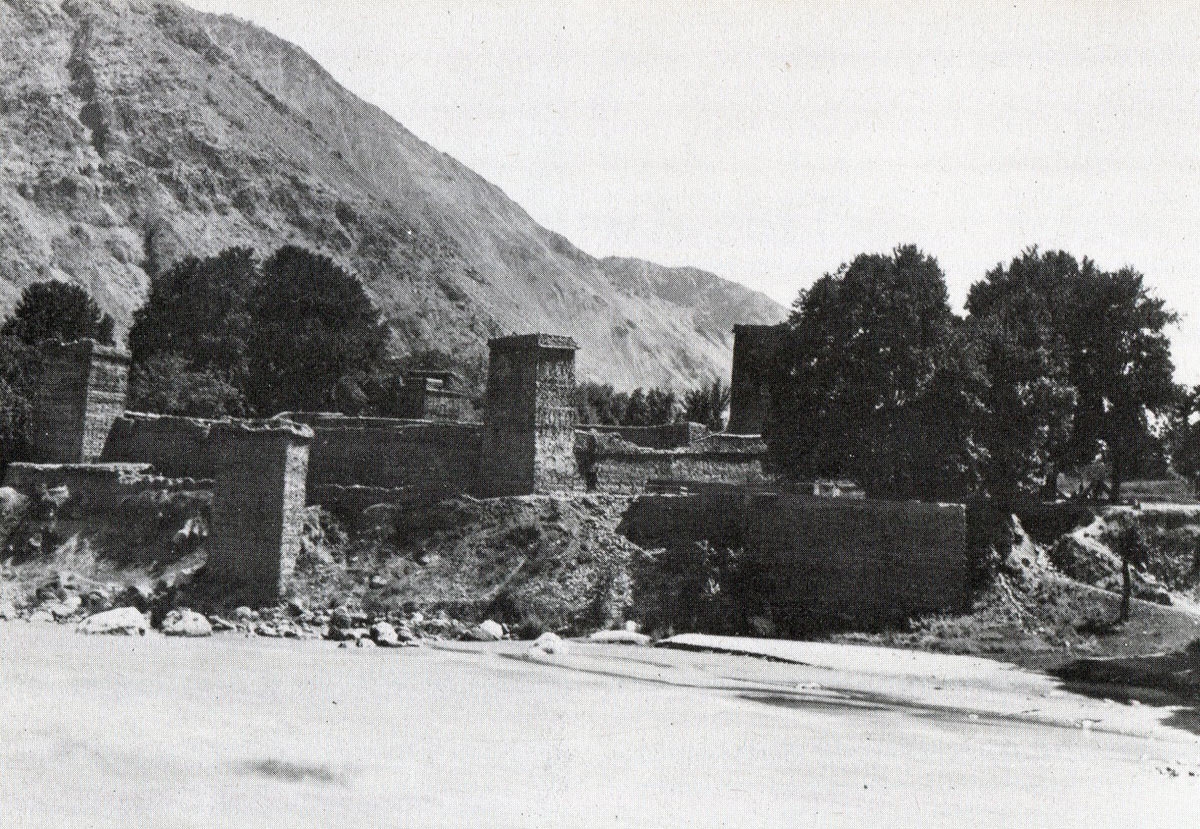

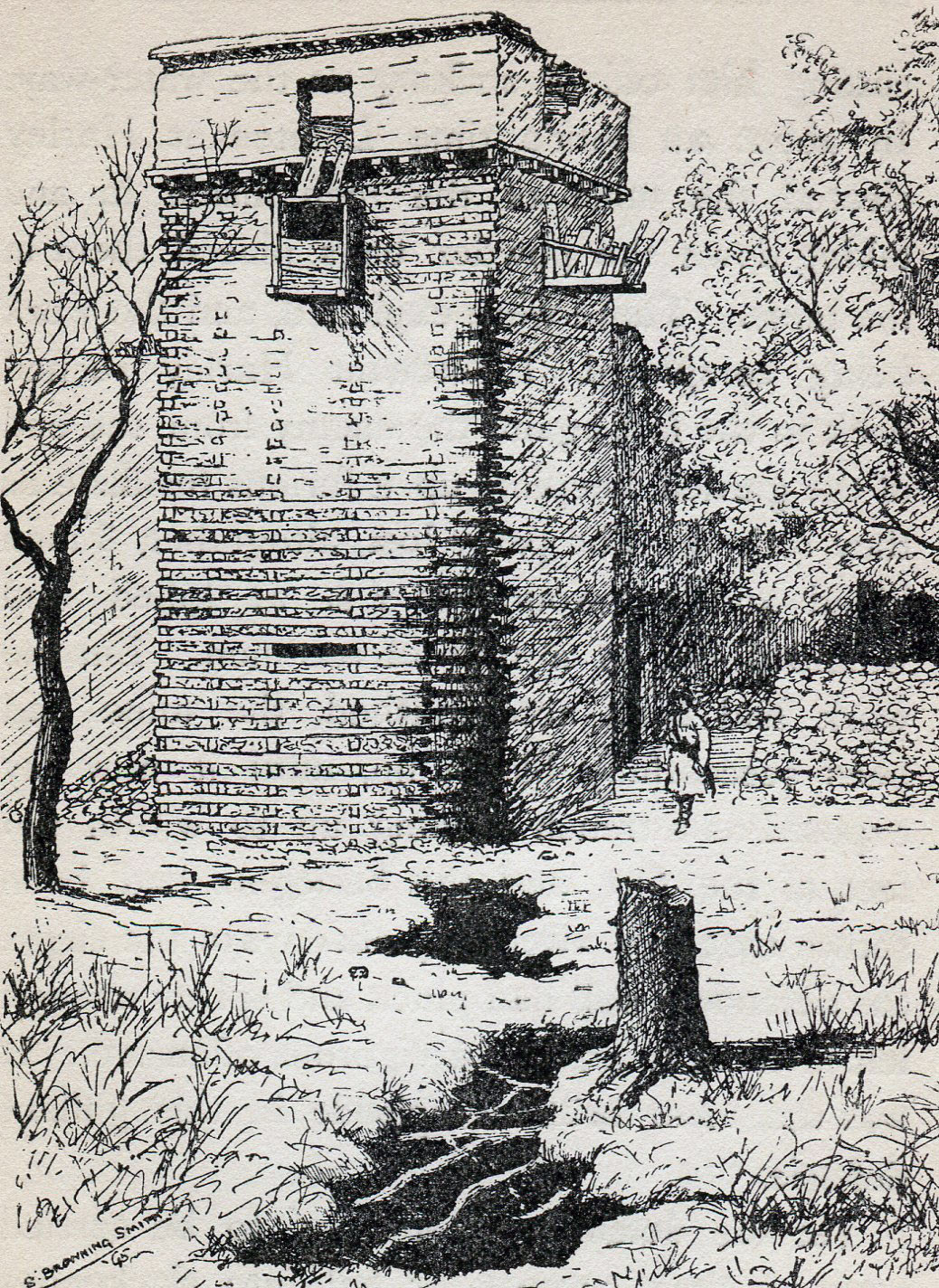

Aligarh comprised inner and outer forts, surrounded by a wide and deep flooded ditch, crossed by a single bridge leading to the main gate.

The forts mounted 73 guns of a wide range of calibres, with reserves in the arsenal.

The only point of attack was the main gate.

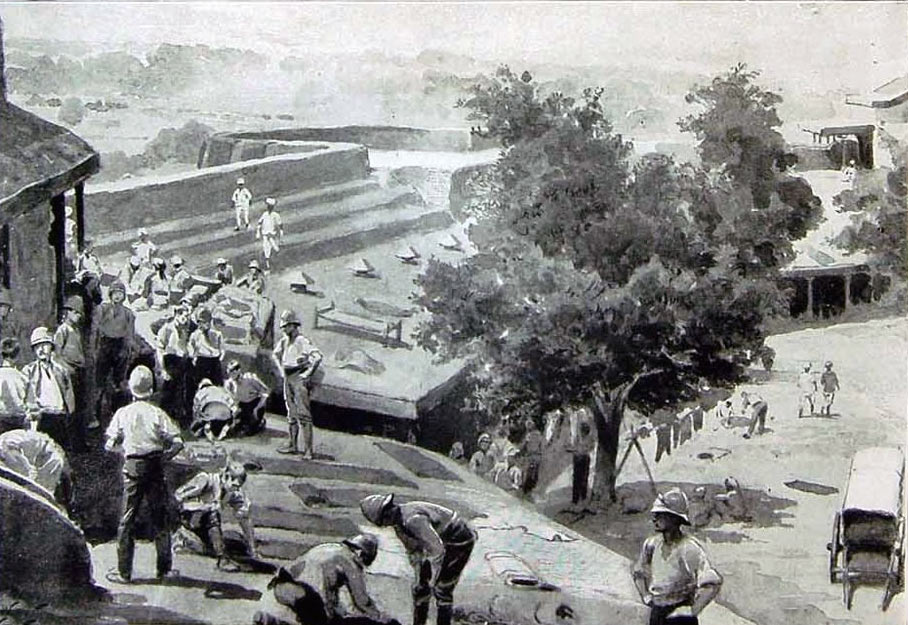

Lake constructed two batteries to fire on the gate and a storming party was formed of four companies of HM 76th Regiment and four companies of the 4th Bengal Native Infantry, with a further Bengal Native Infantry battalion in support.

The storming party, led by a forlorn hope, moved towards the main gate of the fortress at 3am on 4th September 1803.

A party of Mahratta infantry were collected around a camp fire outside the gate.

Soldiers of the 76th moved forward, with the intention of panicking the Mahratta party into running for the gate, so that the British soldiers could follow them through before the gate could be shut.

Inadvertently, all the Mahrattas were killed or severely wounded, leaving none to run to the gate and forcing the British soldiers to retire before they were spotted from the fortress walls.

At dawn on 5th September 1803, the storming party rushed the gate, but were unable to penetrate the gatehouse against determined Mahratta resistance.

A six-pounder gun was brought forward and then a twelve-pounder and after a number of cannon balls had been discharged into the gate it gave way and the storming party took the gatehouse.

A lengthy circular road led round to a second gate.

The storming party raced along the road, under a heavy fire from the ramparts and quickly penetrated the second gate.

The storming party now faced a causeway leading to the main fortress with a third gate, which they seized before it could be closed.

The storming party was now in the passageway between the outworks and the main fortress and were subjected to a heavy fire before it could reach the fourth gate.

While the twelve-pounder was brought up and deployed in vainly battering at this gate, soldiers of the 76th entered a wicket gate and penetrated onto the ramparts.

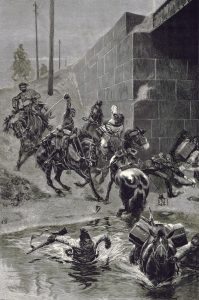

At this point the Mahratta garrison despaired of holding the fortress and attempted to escape, many being drowned in the fortress moat, while others were cut down by HM 27th Light Dragoons waiting on the far side of the fortress.

Lake’s troops occupied the fortress.

The casualties in the assault were 5 officers and 19 soldiers of the 76th killed and 4 officers and 62 soldiers wounded, with overall British and Bengali casualties 52 killed and 205 wounded.

Mahratta casualties in the assault on Aligarh are not recorded.

On 7th September 1803, Lake marched on to Delhi, leaving a sepoy battalion to garrison Aligarh and despatching Macan’s cavalry brigade to pursue a body of Mahratta horse that was attacking a small force of Bengal sepoys at Shekoabad.

On 8th September 1803, Lake reached the fortress of Koorjah to find the garrison had left, not wishing to be subjected to a storm, as at Aligarh.

Lake on that day received a letter from the Frenchman, Colonel Perron, saying that he had left Scindia’s service and seeking safe conduct out of Mahratta territory, which Lake gladly gave.

Command of Scindia’s troops in the north now fell to the French officer, Louis Bourquain.

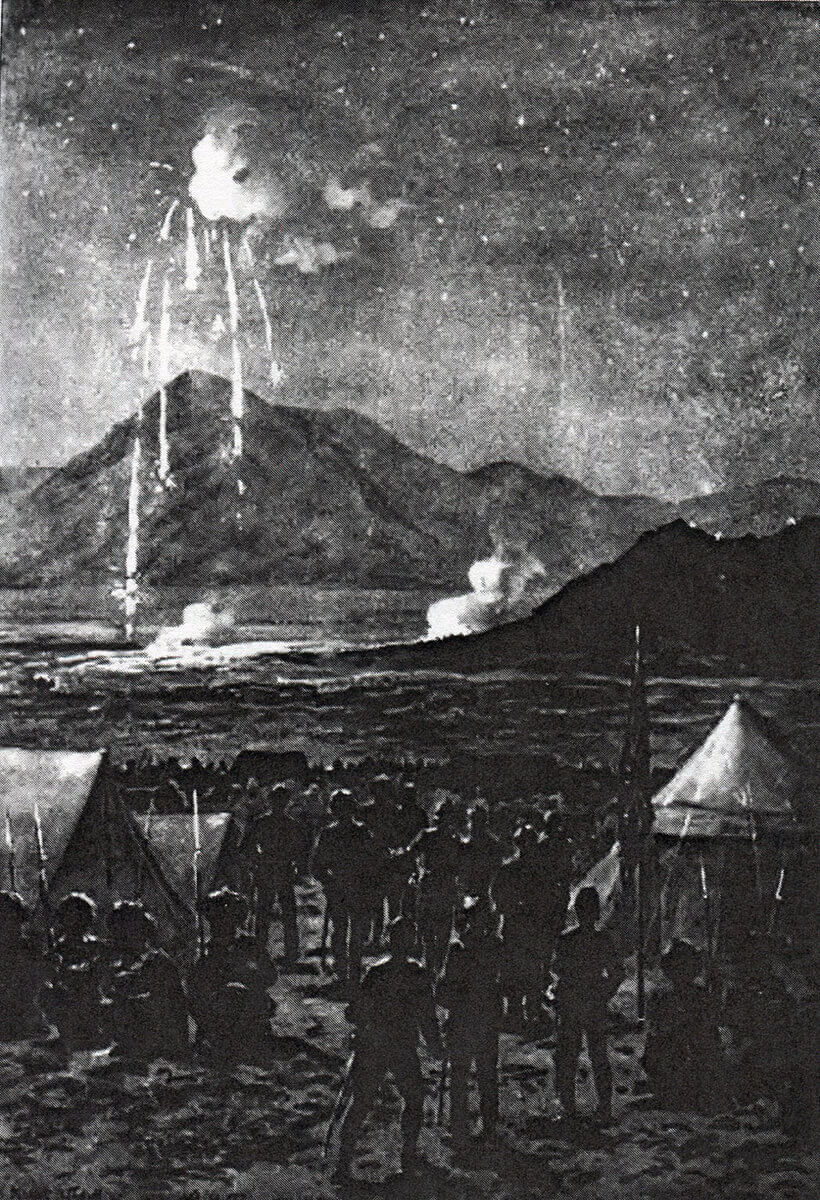

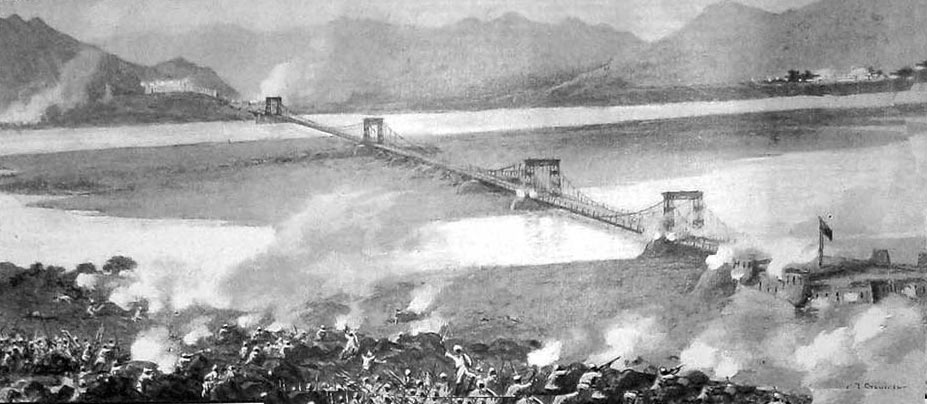

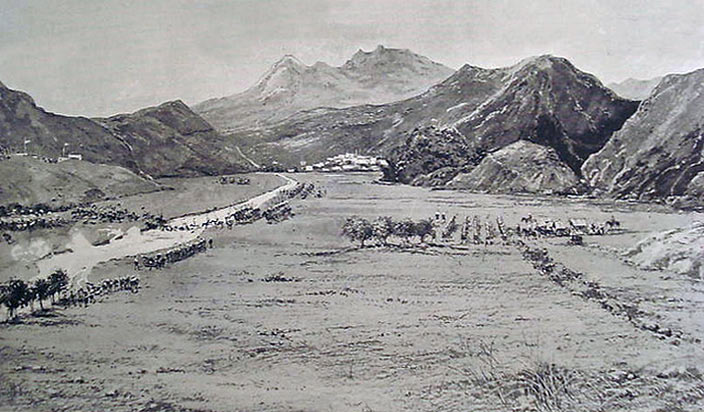

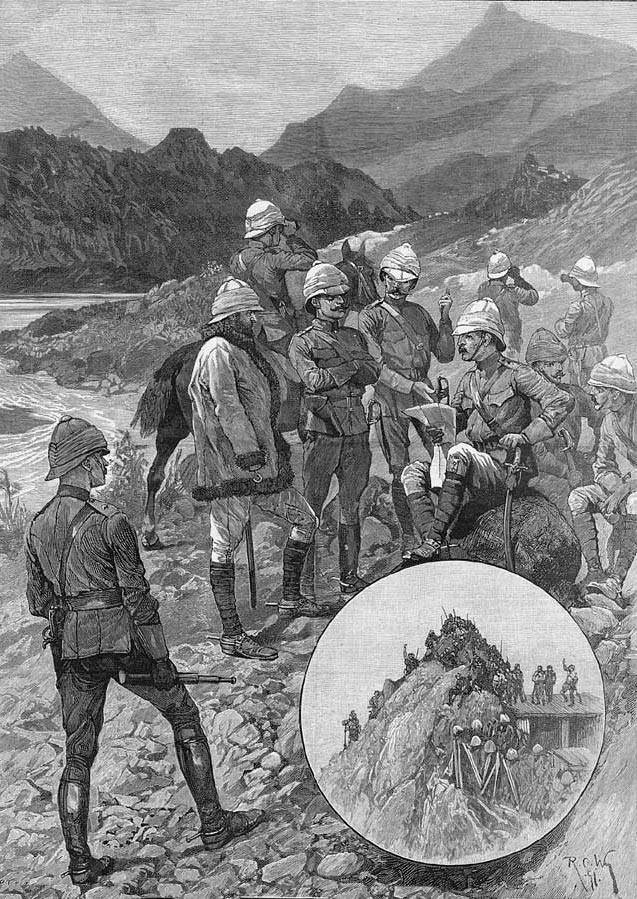

The Battle of Delhi:

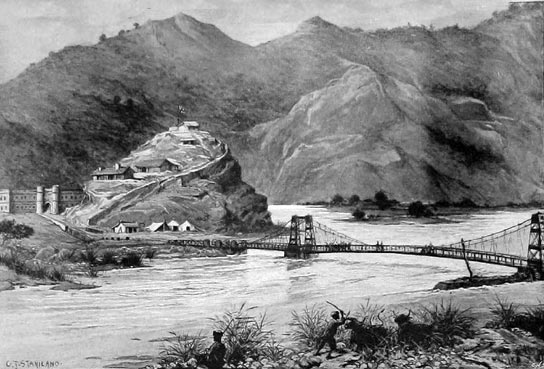

On 10th September 1803, a march of 18 miles brought Lake’s army within 6 miles of the east of Delhi.

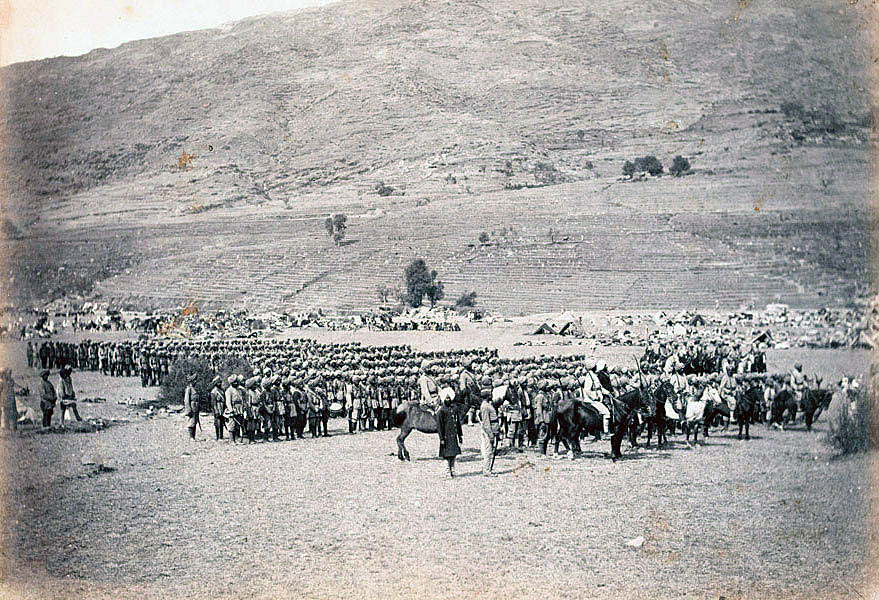

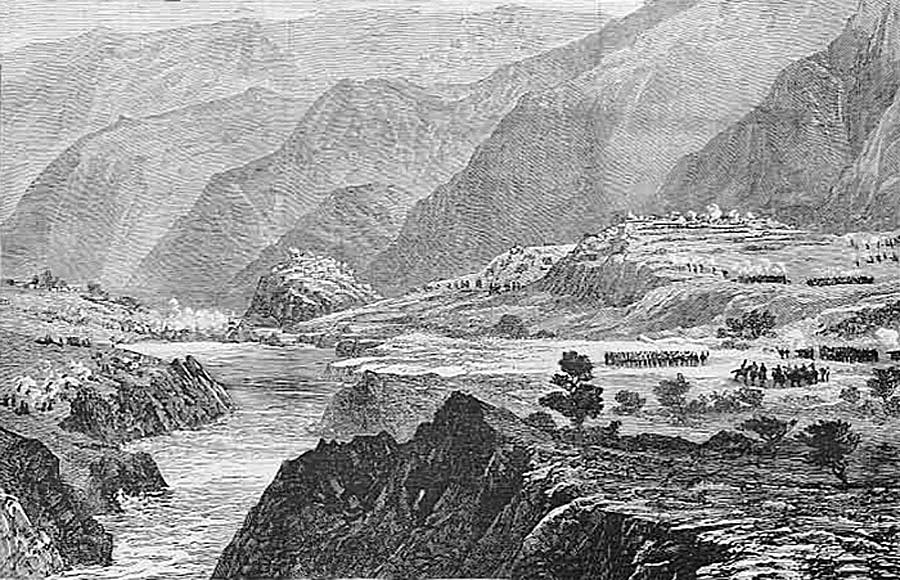

After the long march, Lake’s army was encamping when news came in that Bourquain’s Mahratta army had crossed the River Jumna with 16 battalions of infantry, 6,000 cavalry and several guns and were forming up for an attack.

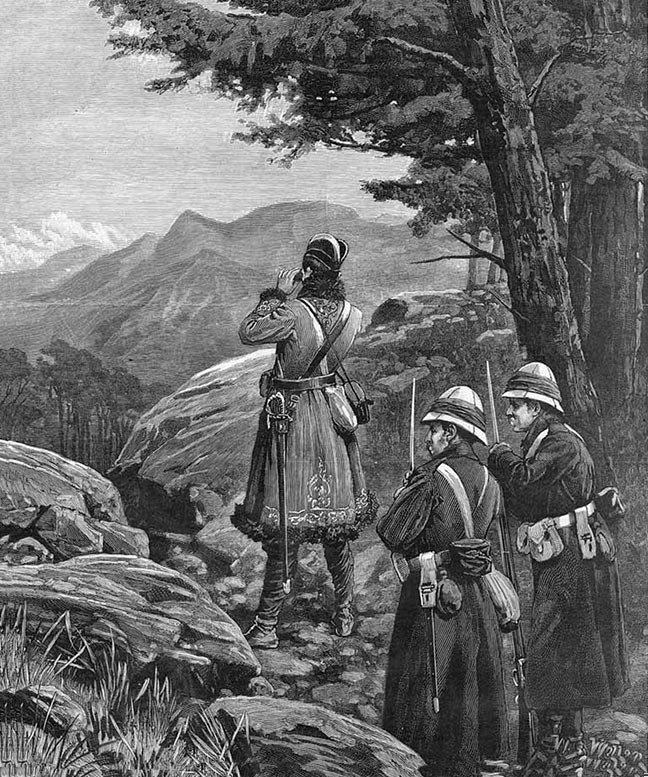

Lake rode out of camp with the three regiments of cavalry, to reconnoitre the Mahratta position.

Lake found Bourquain’s Mahratta army formed up behind previously prepared field fortifications, on raised ground with the River Jumna in its rear.

The Mahratta infantry and guns formed the first line, with swamps covering each flank and the Mahratta cavalry the second line.

High grass obscured much of the Mahratta position.

The Mahratta guns opened fire on Lake’s cavalry as he conducted his inspection.

Lake sent orders for the infantry to come up for the attack.

While the cavalry waited, they were subjected to a damaging cannonade by the Mahratta guns, in which Lake’s horse was killed and he took his son’s horse, his son mounting the horse of a casualty.

An hour later Lake’s infantry arrived.

After the various detachments, Lake was left with eight and a half battalions of infantry and the three regiments of cavalry, some 4,500 men, with which to attack Bourquain’s 19,000 men.

As his infantry appeared in the distance, Lake ordered the cavalry to fall back, to entice the Mahratta army into an ill-judged advance.

The Mahrattas took the bait, their whole army advancing out of the entrenchments with loud shouts.

The British cavalry continued to withdraw, moving directly towards the advancing infantry, masking their appearance, until, on reaching them, the British cavalry turned to left and right and cleared the face of the infantry.

The British infantry were formed with HM 76th on the right and then: 2nd/12th BNI, 2nd/15th BNI, 2nd/2nd BNI, 1st/14th BNI and 1st/2nd BNI.

The British cavalry formed behind the right wing of the infantry line.

A force of Sikh cavalry in the Mahratta service made to move behind Lake’s left flank and rear.

This move was countered with a force of British cavalry and galloper guns and the left-hand Bengal Native Infantry battalion turning outwards and positioning its right flank on a village.

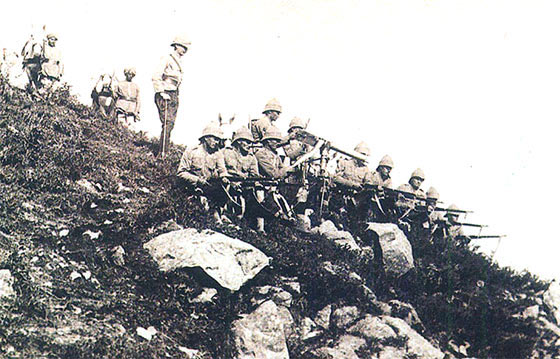

With these deployments completed under a heavy Mahratta cannonade of round, grape and chain shot, Lake began the advance of his infantry line, marching at the head of HM 76th Regiment.

Under the continuing Mahratta artillery bombardment, the British infantry advanced to within one hundred yards of the Mahratta infantry line, before halting, firing a volley and charging.

The Mahratta infantry broke and fled.

Lake ordered his infantry line to halt and form ‘column of companies’. The British cavalry galloped through the gaps thereby created in the line and hunted the fleeing Mahratta troops to the banks of the River Jumna, finishing the rout by bombarding the fugitives with the galloper guns that accompanied the cavalry.

A part of the Mahratta army continued along the river bank pursued by Lake’s infantry, until all the Mahratta guns and stores had been captured.

At the end of the battle, it was estimated that Lake’s troops had been on their feet for 16 hours, much of it during the hottest part of the day.

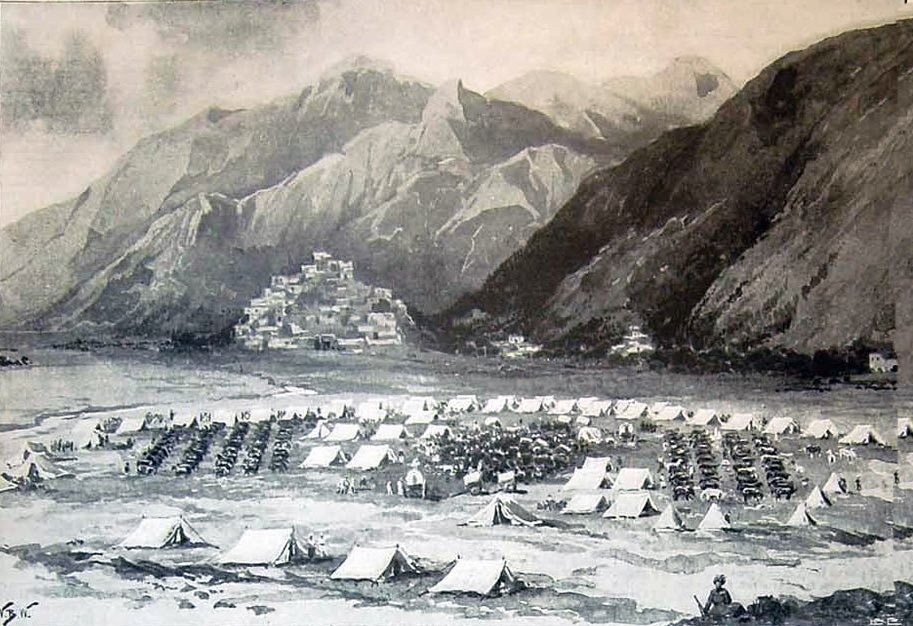

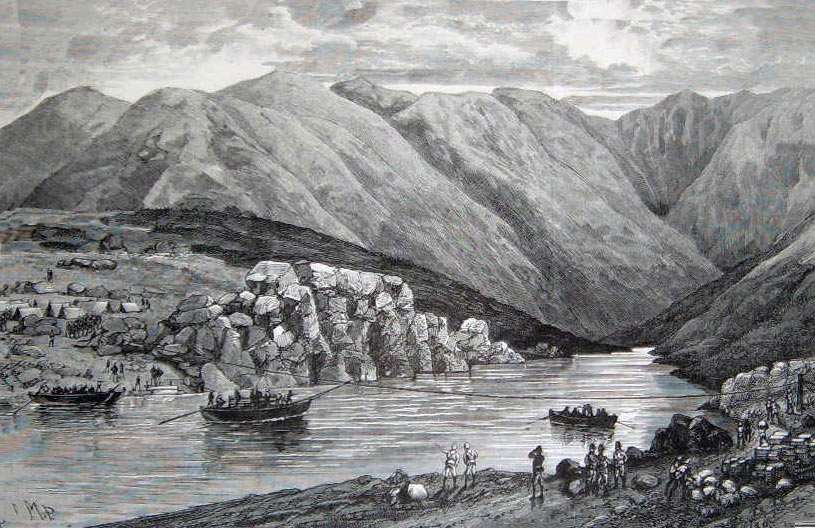

Lake’s army encamped on the bank of the River Jumna opposite Delhi.

British casualties in the battle were 478 killed, wounded or missing. Of these, 1 officer and 136 men were casualties in HM 76th Regiment. 170 British cavalry horses were lost.

The Mahratta army was estimated to have suffered 3,000 killed, wounded or missing.

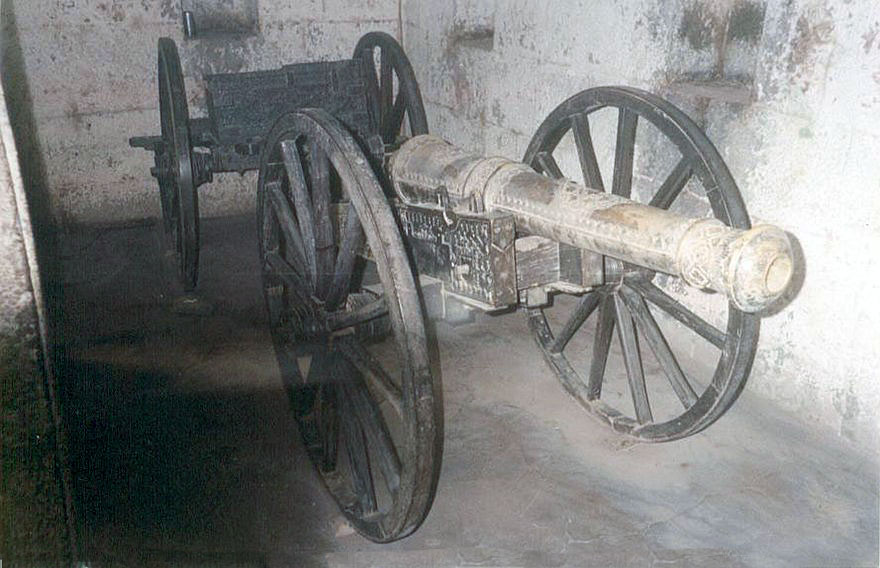

The British took 68 Mahratta guns, described by Fortescue as ‘all admirably made after a French design’.

On 14th September 1803, Bourquain and four other French officers surrendered to Lake.

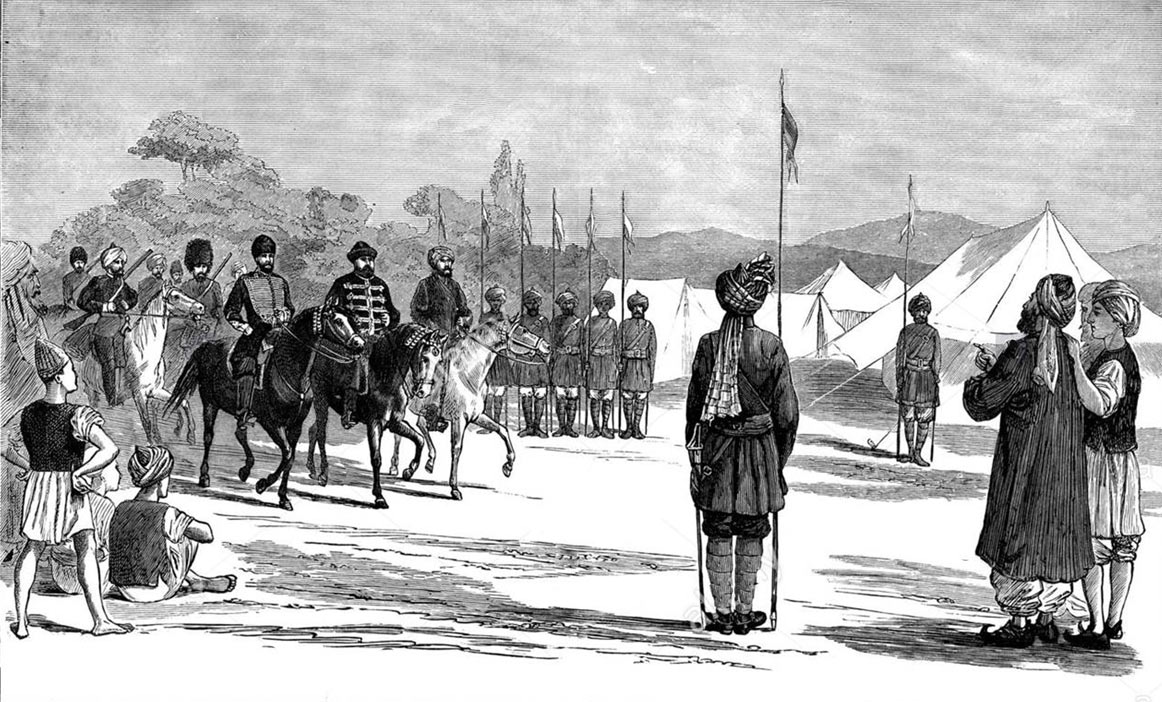

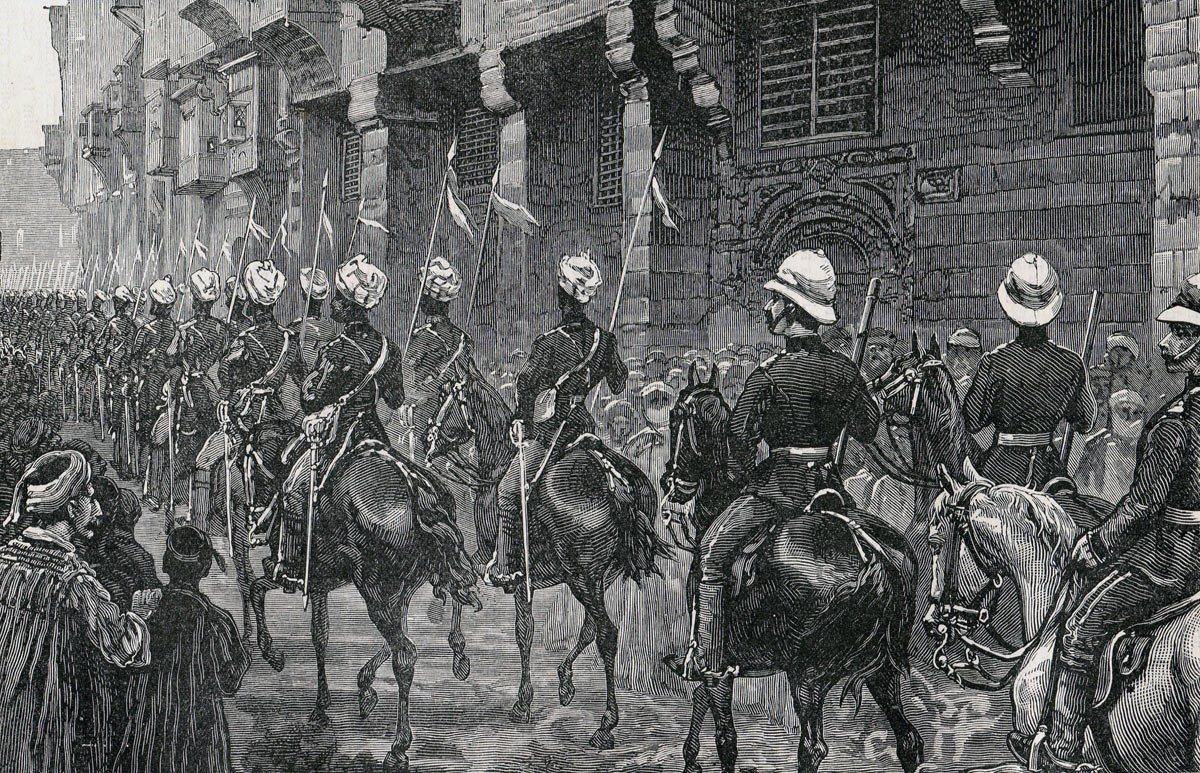

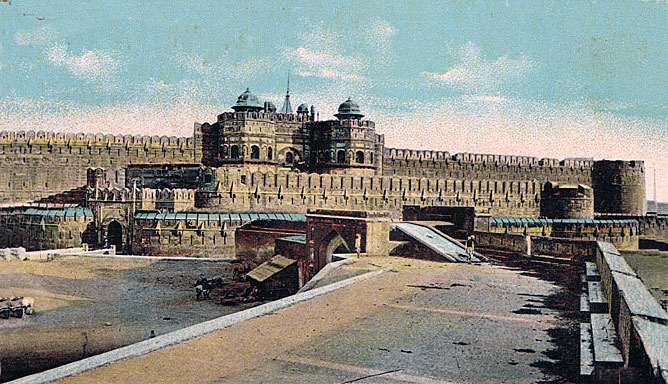

On 16th September 1803, the Moghul Emperor, Shah Alum, welcomed Lake into the City of Delhi.

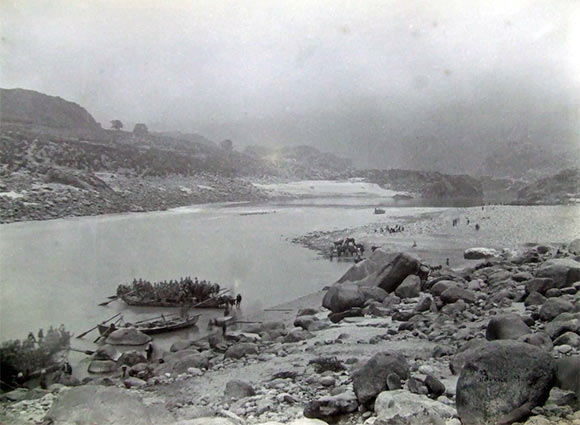

On 24th September 1803, Lake marched for Agra, down the banks of the River Jumna, while his artillery was transported in boats.

On 2nd October 1803, Lake reached the Mahratta arsenal of Muttra, where the various British and Bengal infantry and cavalry regiments that had been detached re-joined the main army. Four more French officers surrendered to Lake.

On 4th October 1803, Lake reached Agra.

On 10th October 1803, Lake launched assaults on the city which led to the surrender of the garrison on 18th October 1803.

Agra was a key fortress, its capture considerably enhancing the standing of the East India Company and providing large quantities of military stores for Lake’s army, with significant sums of cash as prize money.

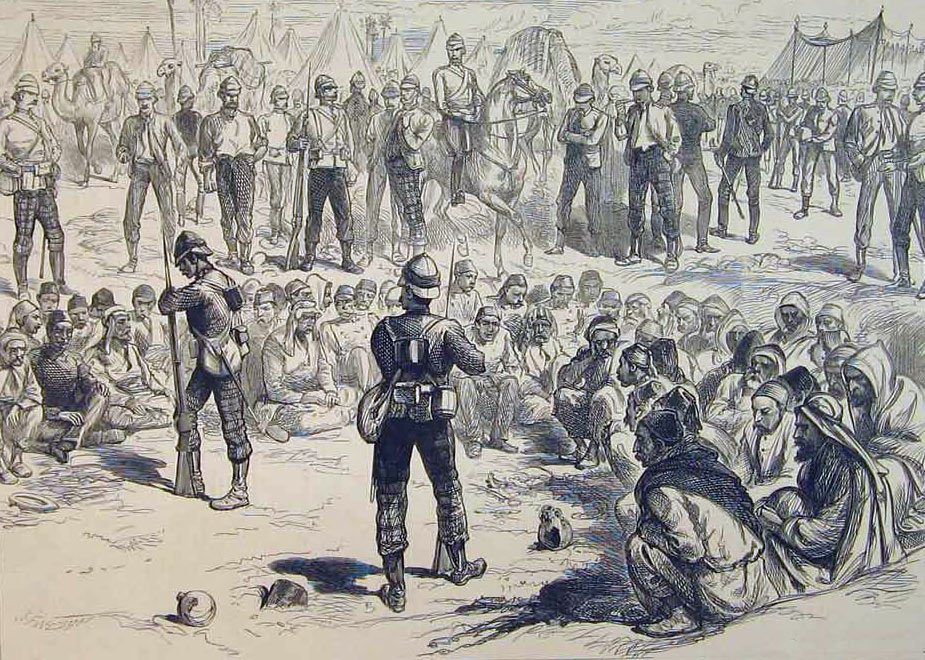

Lake’s army was further reinforced by 2,500 Mahratta prisoners volunteering to join the East India Company service and the arrival of 5,000 horsemen sent by the Rajah of Bhurtpore to join the British.

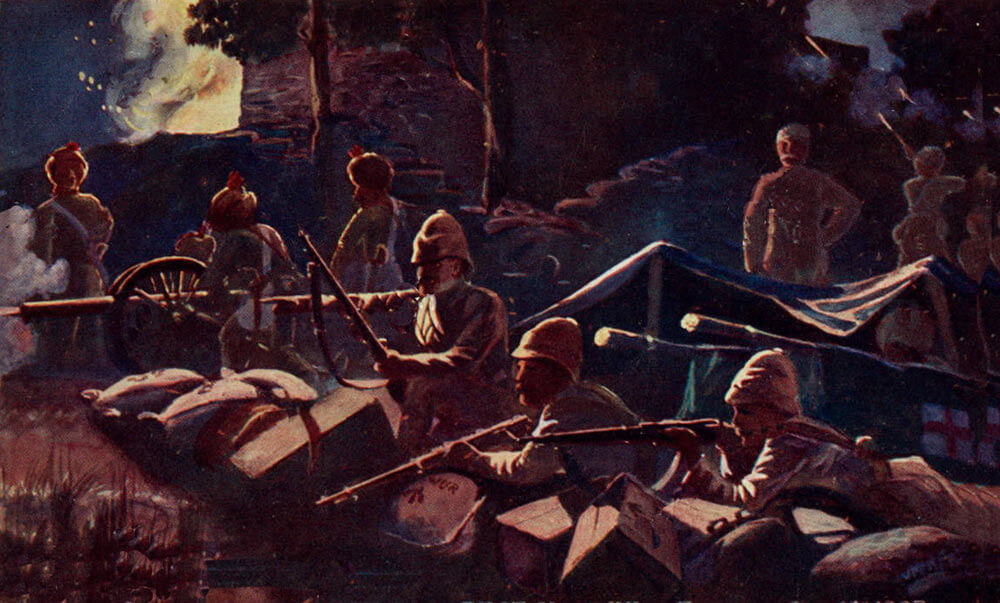

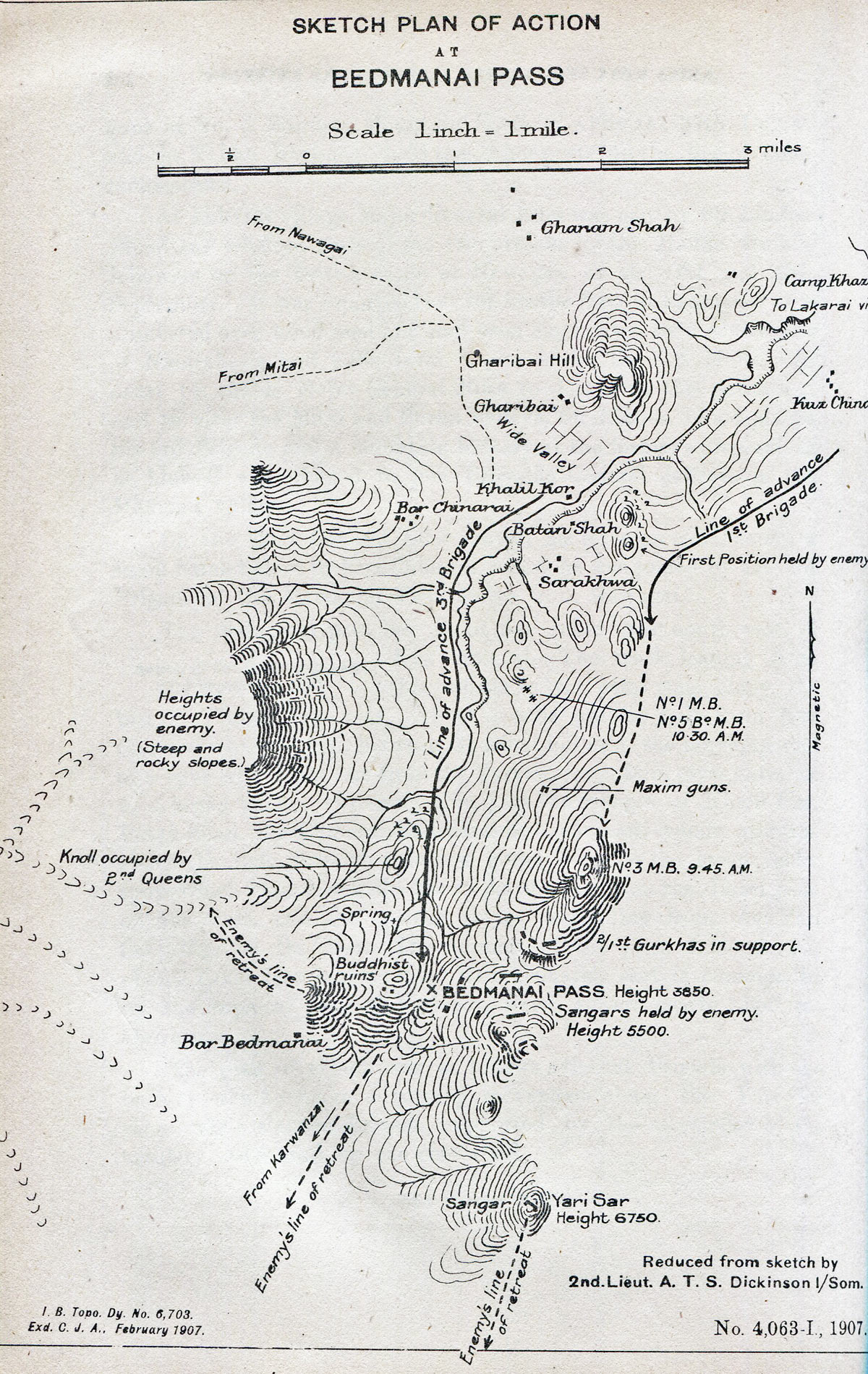

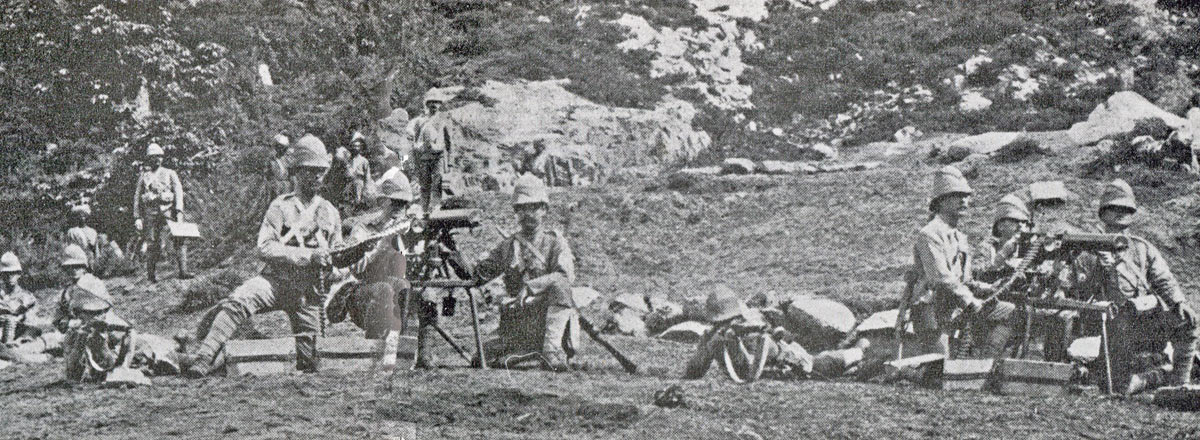

The Battle of Laswaree:

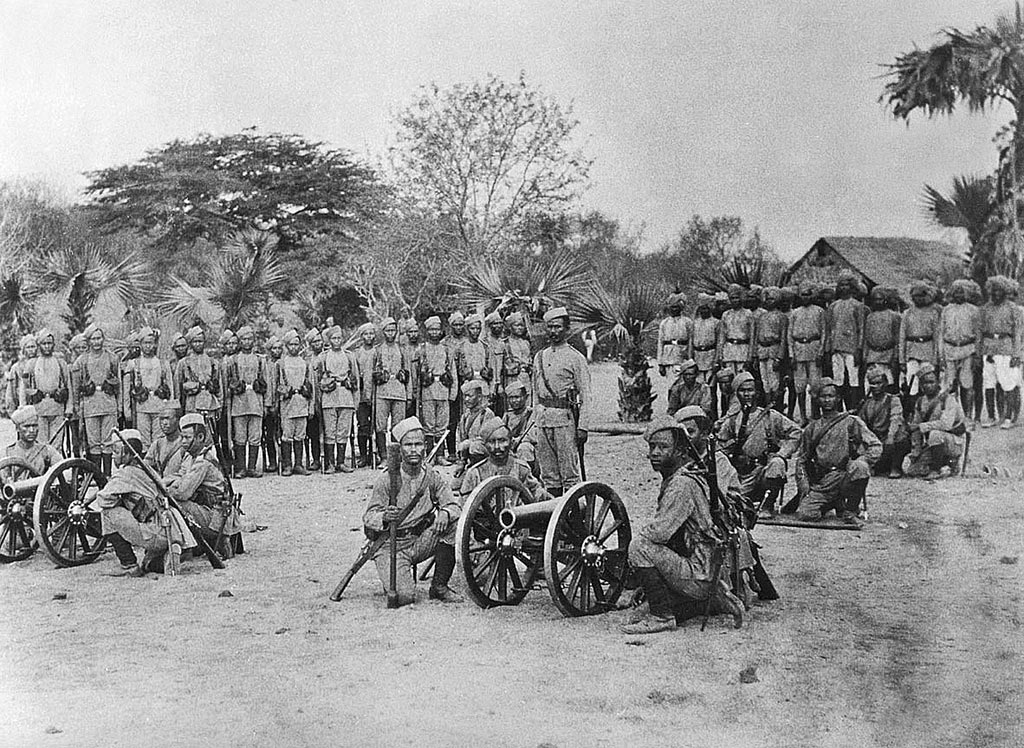

In spite of his defeats at Aligarh and Delhi and the loss of much of the Agra garrison, Scindia Rao still deployed an army of 9,000 infantry, 5,000 horsemen and a substantial artillery in Hindoostan (the North of India around Delhi).

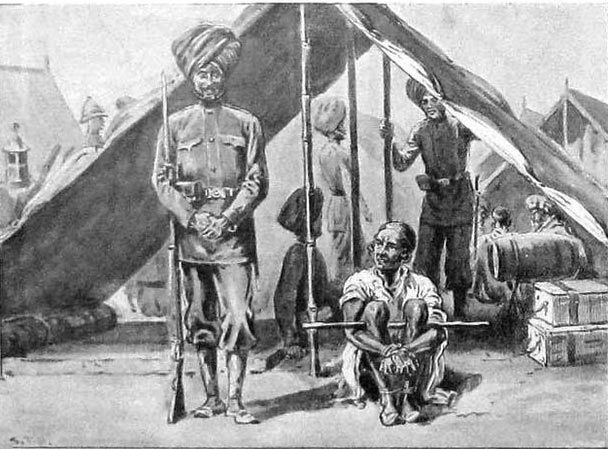

The senior French officers having surrendered to the British, this army was commanded by a Mahratta general, Abaji.

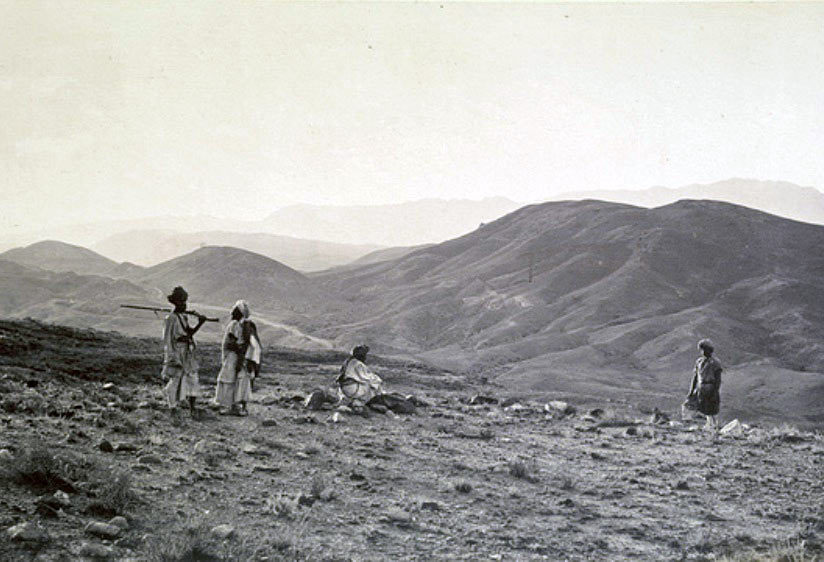

Lake intended to bring Abaji’s army to battle and on 27th October 1803 he marched west, impeded by heavy rain.

On approaching Futtehpoor, the sound of the Mahratta guns could be heard.

Lake left his heavy guns and baggage at Futtehpoor and hurried forward to engage the Mahrattas.

On 31st October 1803, Lake reached the place where Abaji had encamped the night before.

At 11pm that evening, Lake set off with his cavalry in pursuit of the Mahratta army, leaving his infantry to follow.

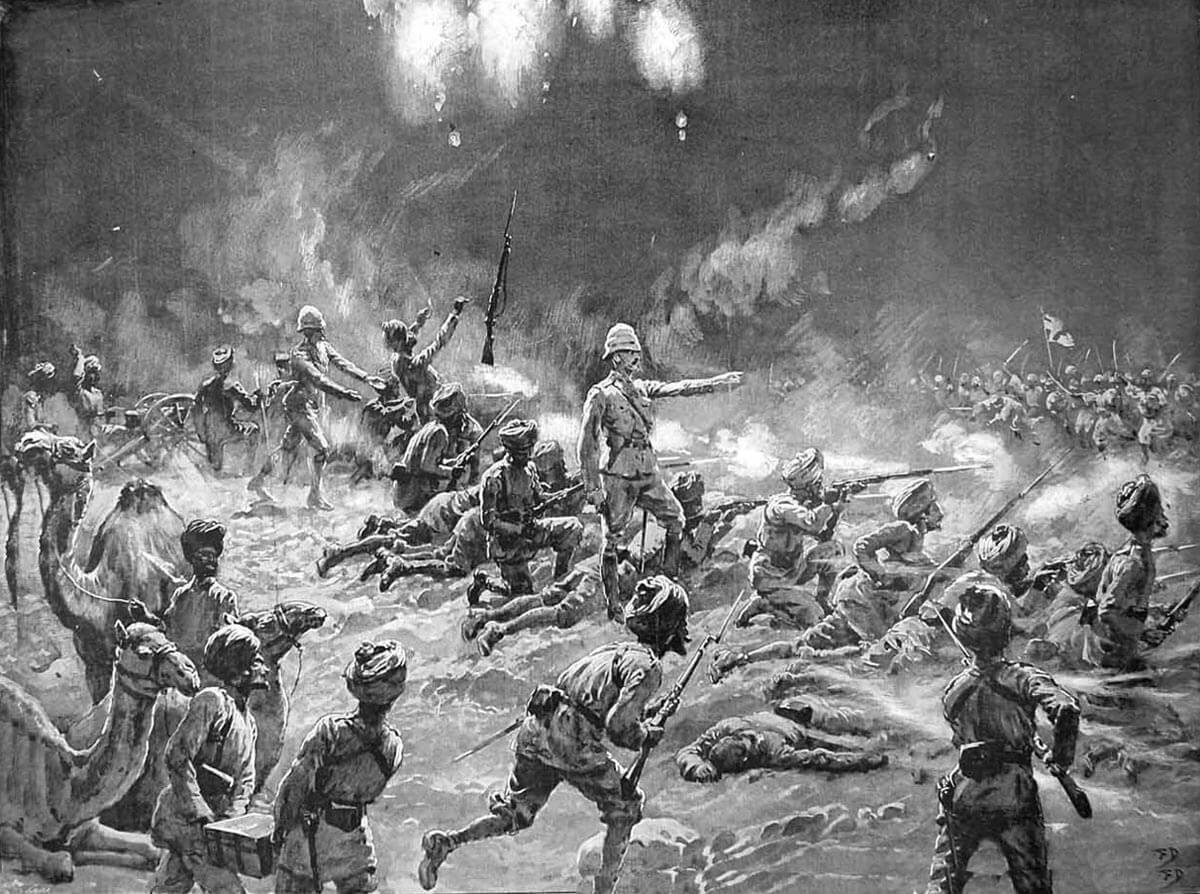

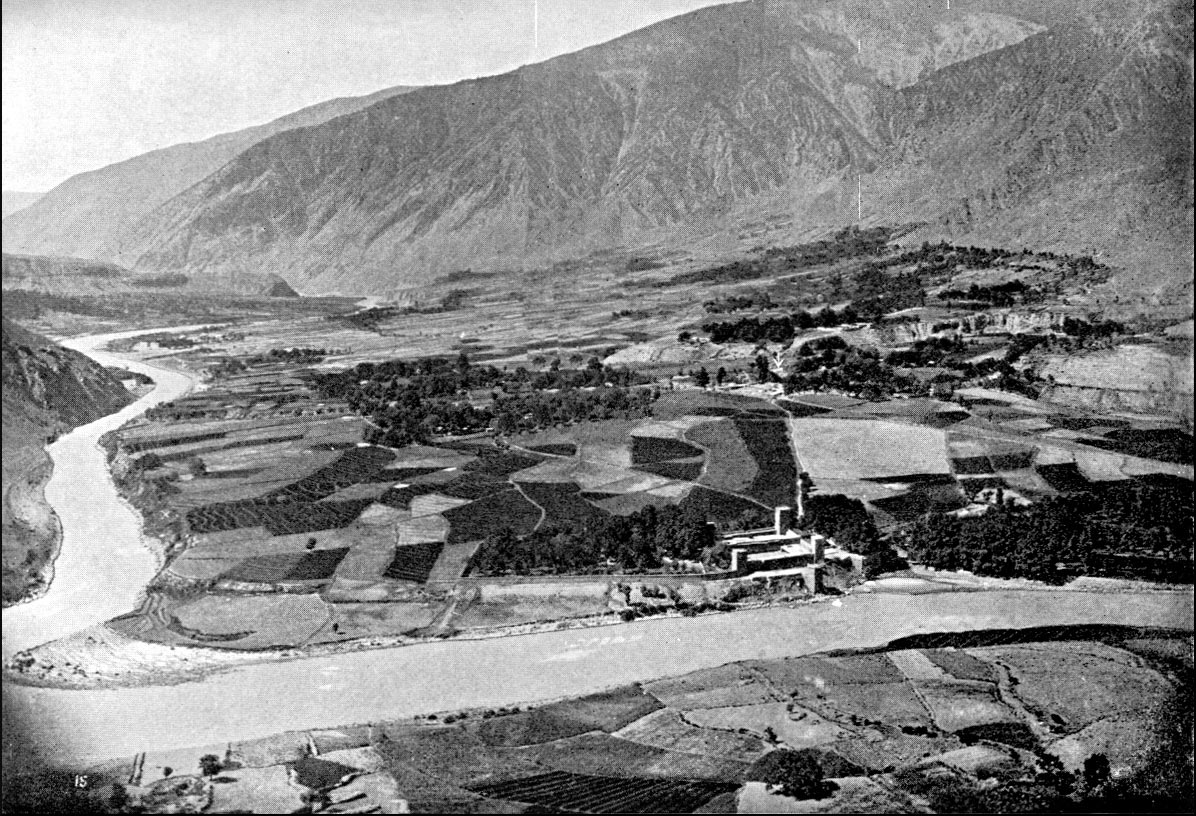

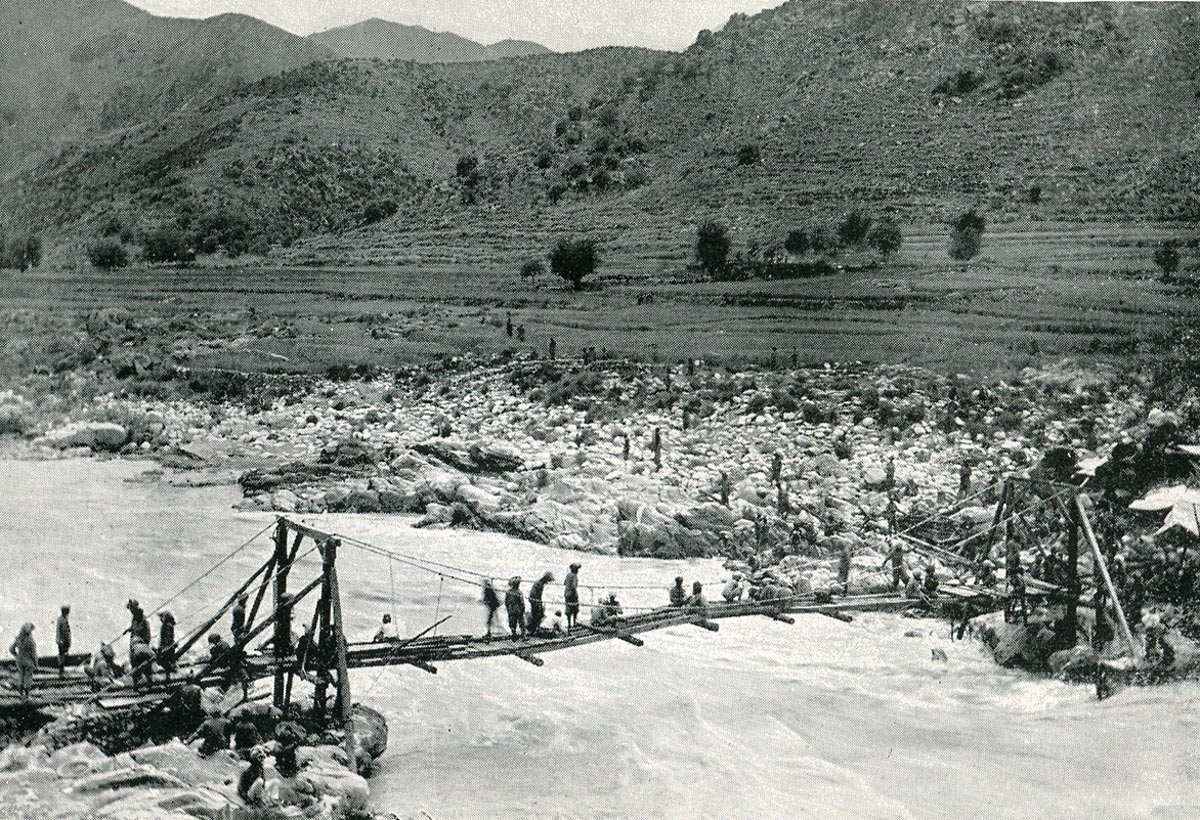

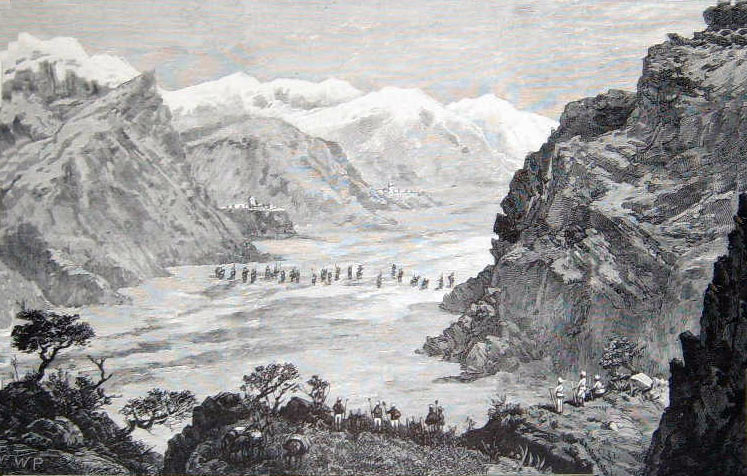

Lake marched 25 miles in six hours, coming up with Abaji’s army at dawn on 1st November 1803.

The Mahratta army was clearly in a hurried and disorganised retreat.

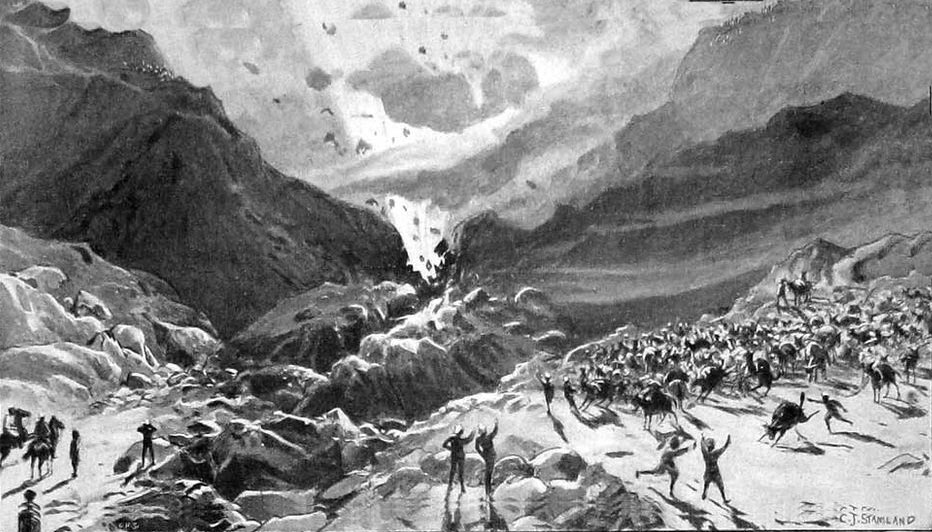

Seeing that Lake’s cavalry was about to attack them, the Mahratta troops cut into the embankment of a large reservoir, flooding the area and slowing Lake’s advance.

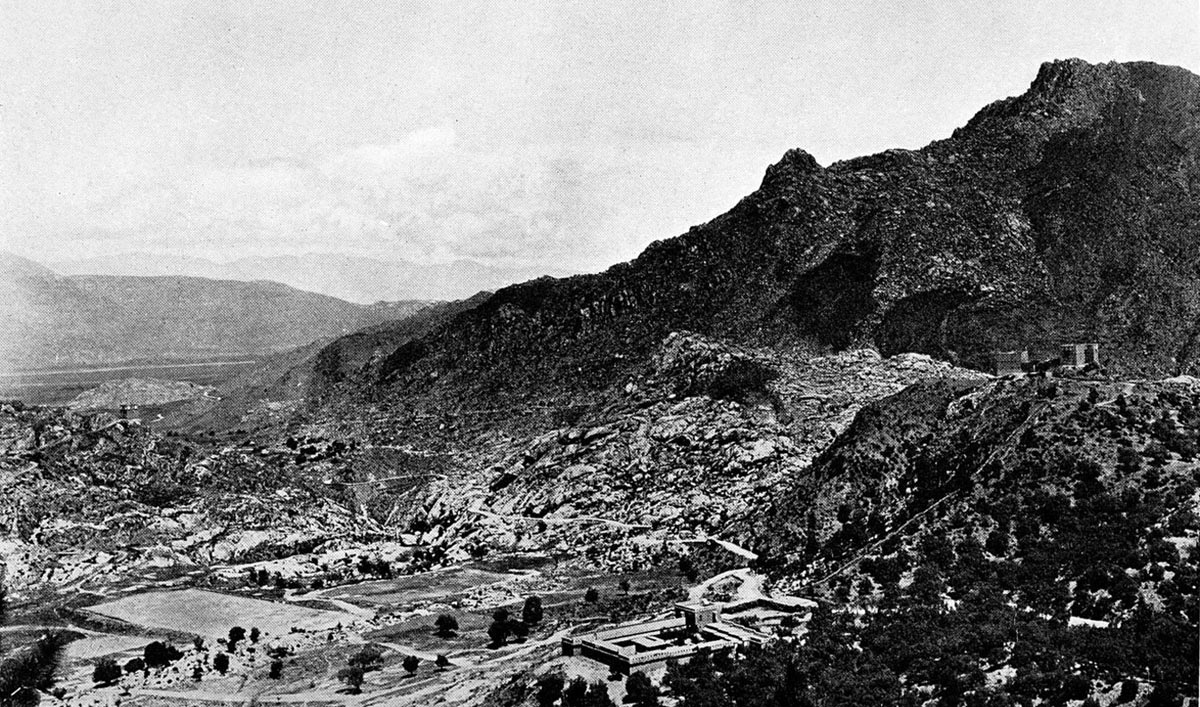

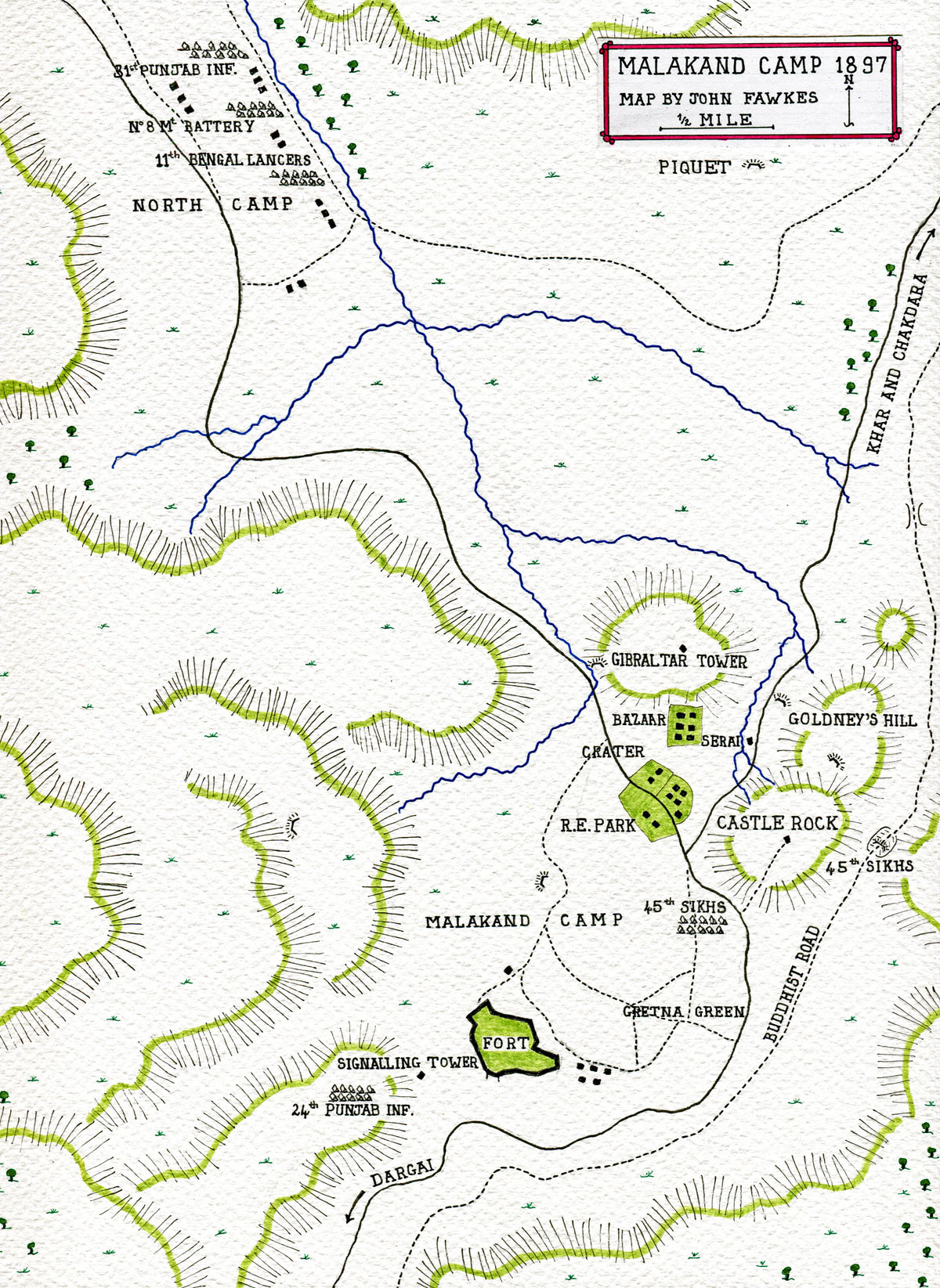

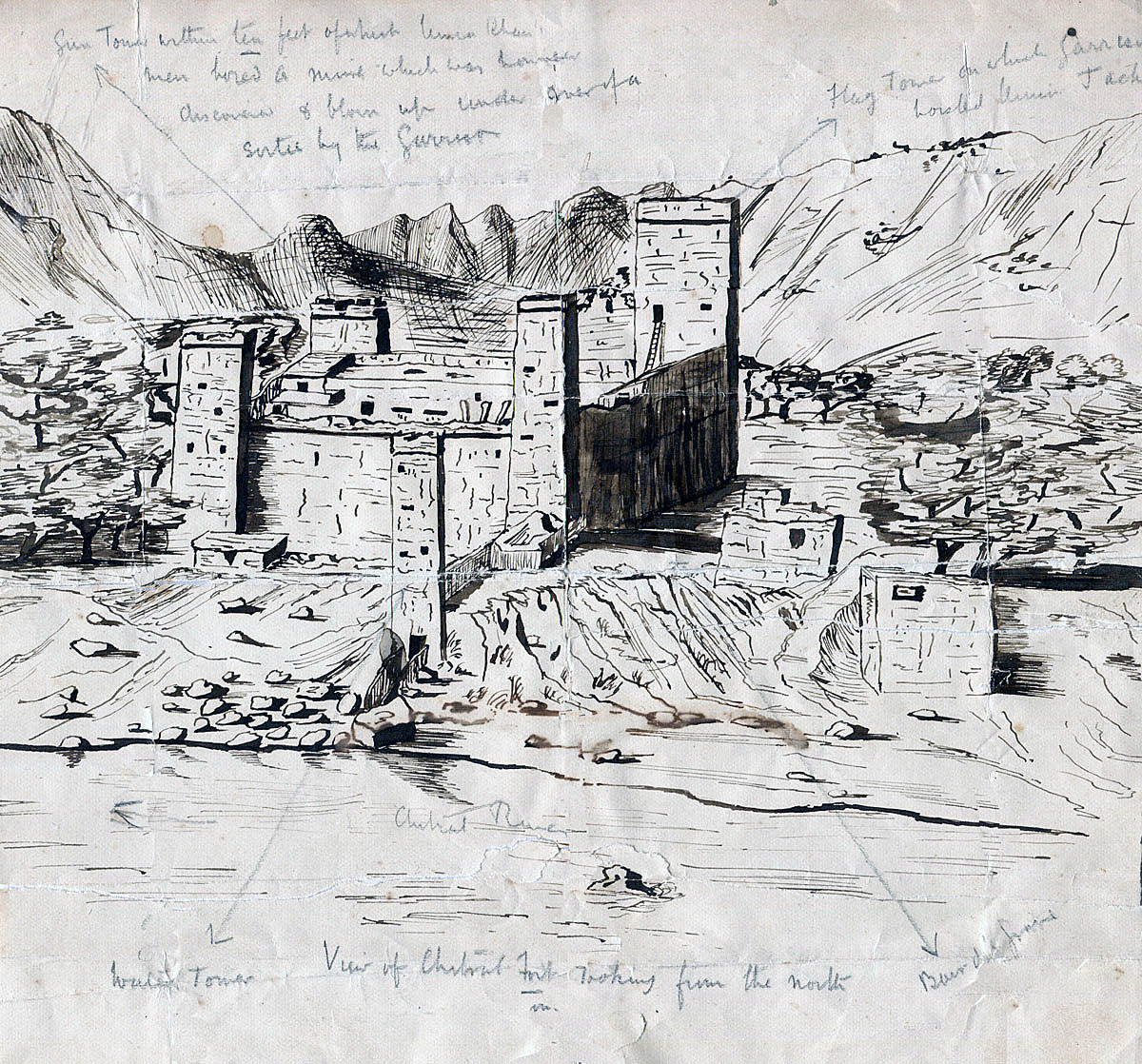

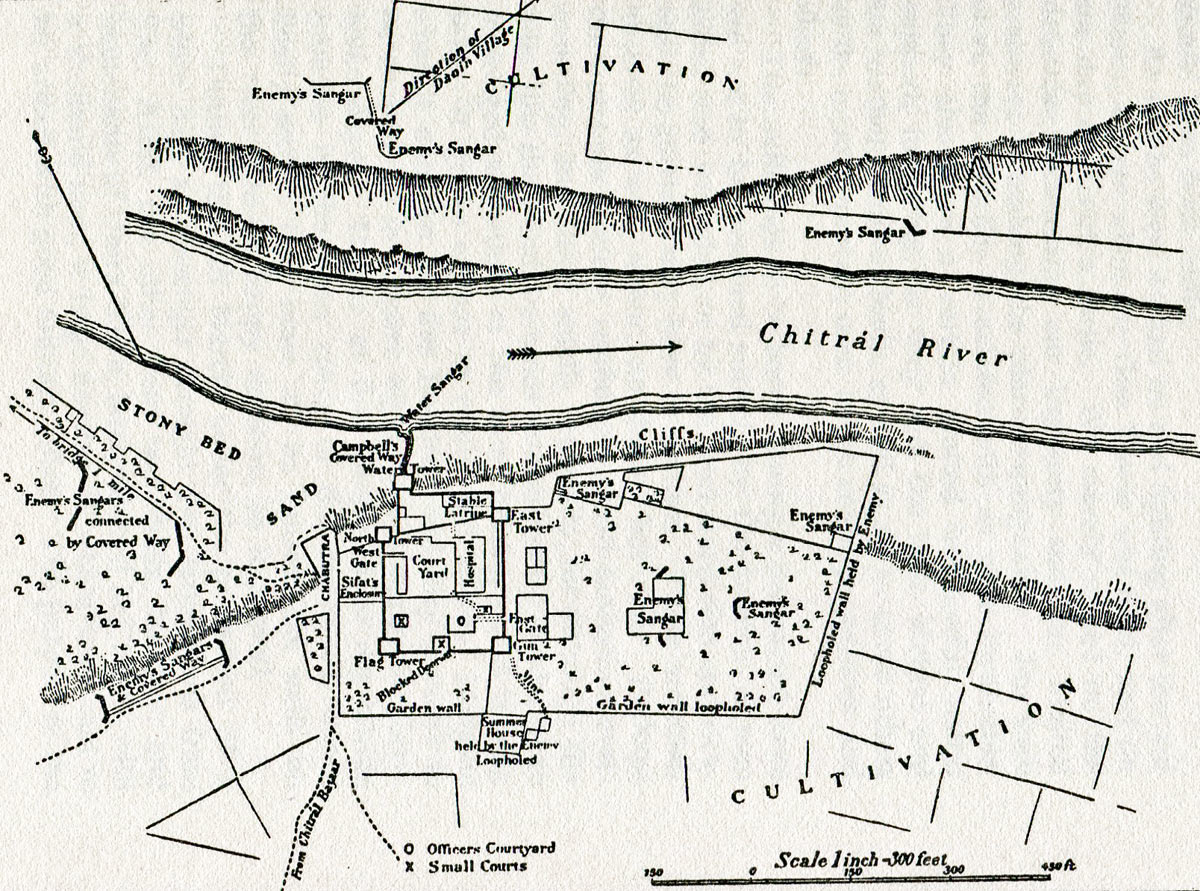

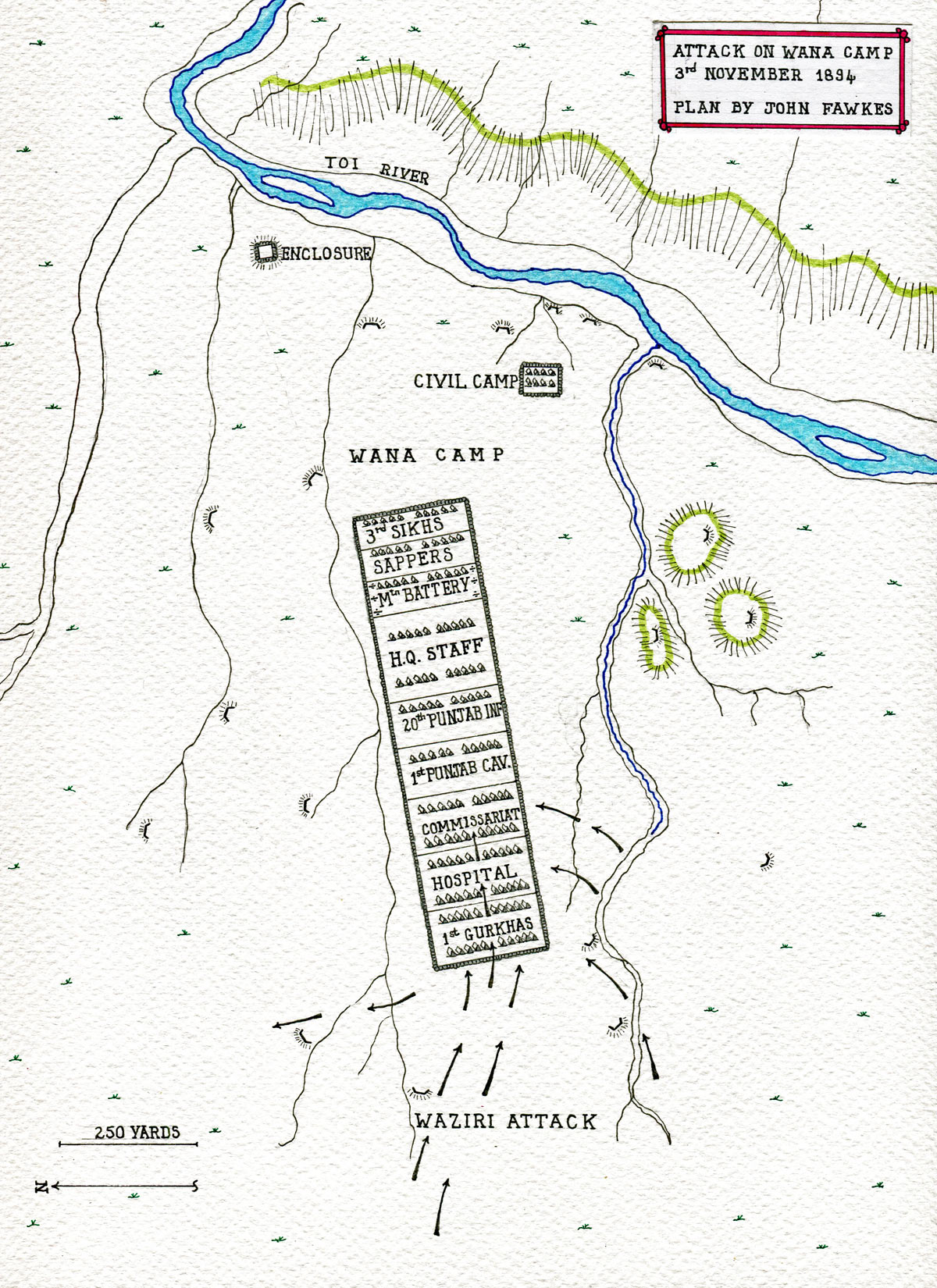

The Mahratta army continued for a short distance before taking up a position between the village of Laswaree, on its right and the fortified village of Mohaulpore, on its left.

These two villages were on the north side of a steep-banked stream.

The Mahratta line was fronted by an area of tall grass that masked their positions and concealed their artillery, which comprised 72 guns.

In addition, the movement of large numbers of troops threw up dust clouds that increased Lake’s difficulty in resolving whether the Mahrattas were halting to give battle or continuing their retreat.

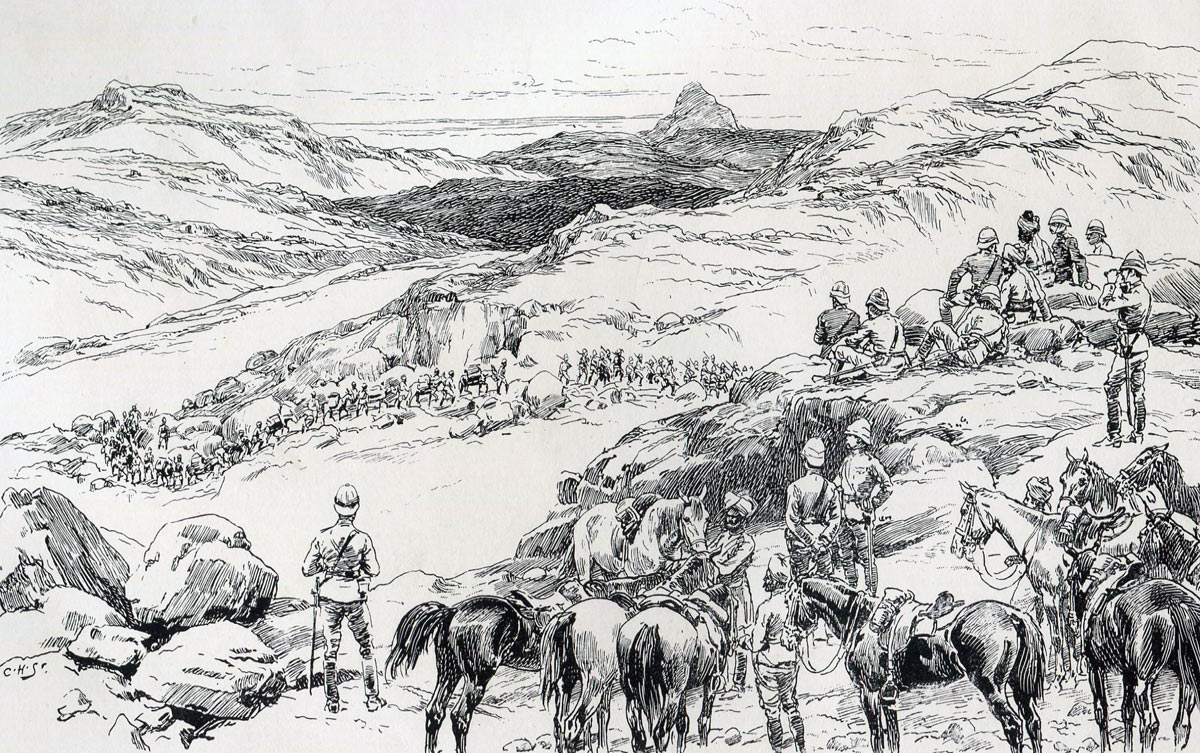

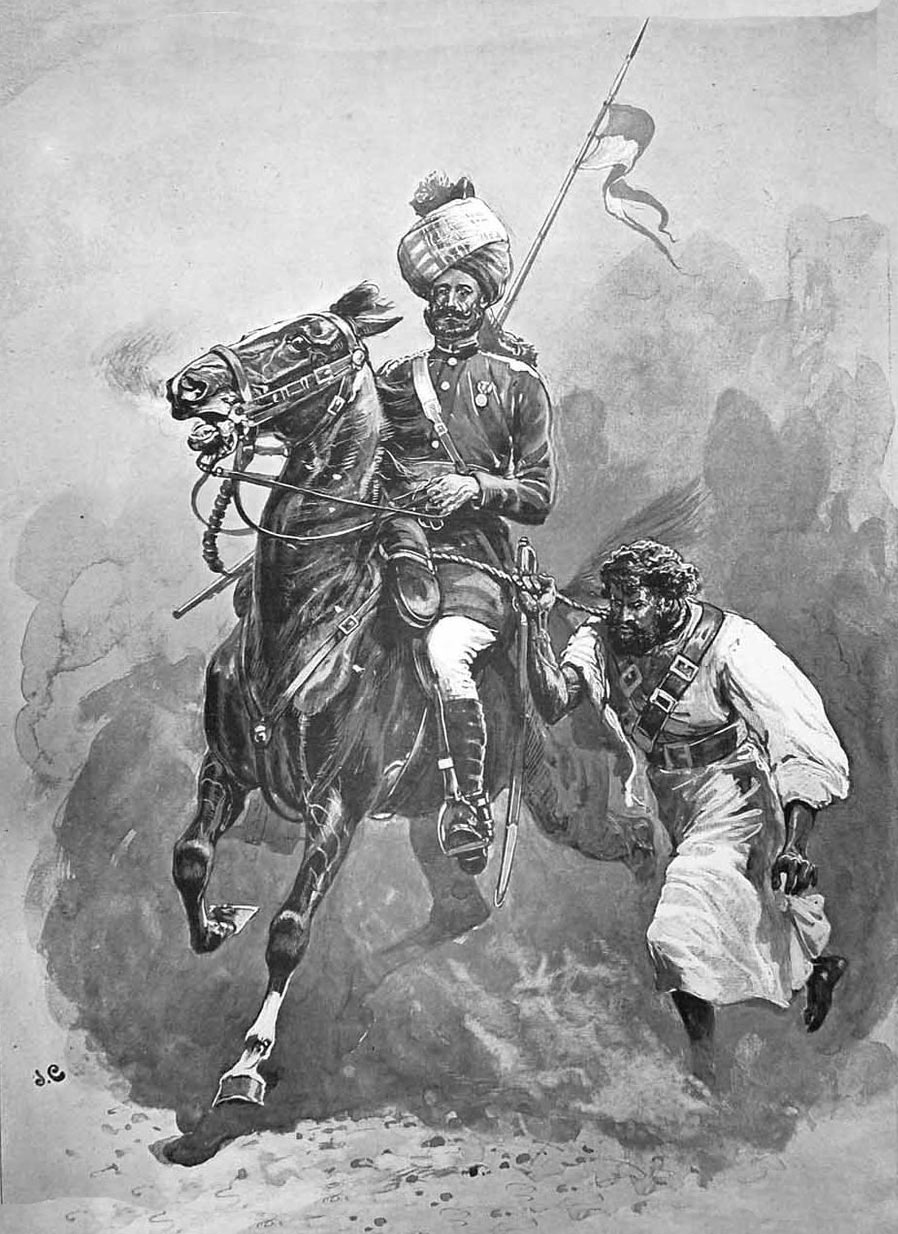

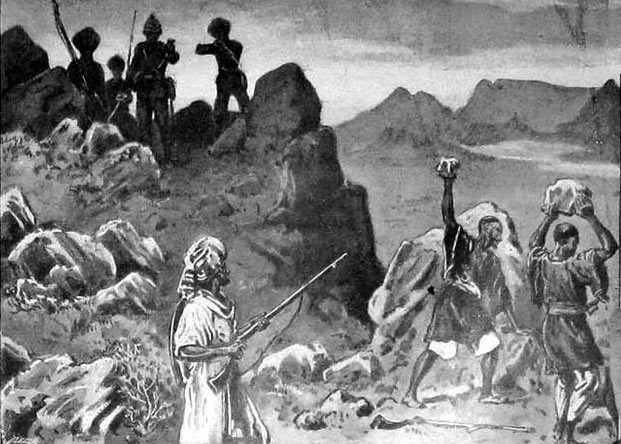

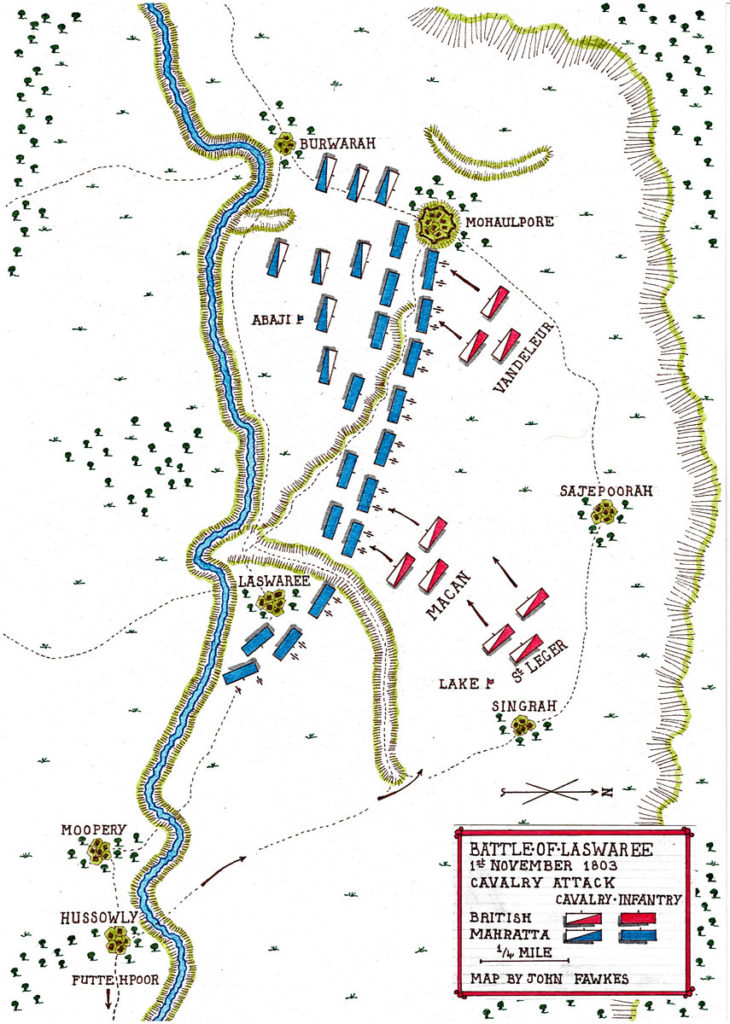

Lake’s cavalry, coming up on the south bank of the stream, crossed to the north bank and approached the Mahratta right flank.

Lake decided to launch his cavalry in attack, without awaiting the arrival of the infantry.

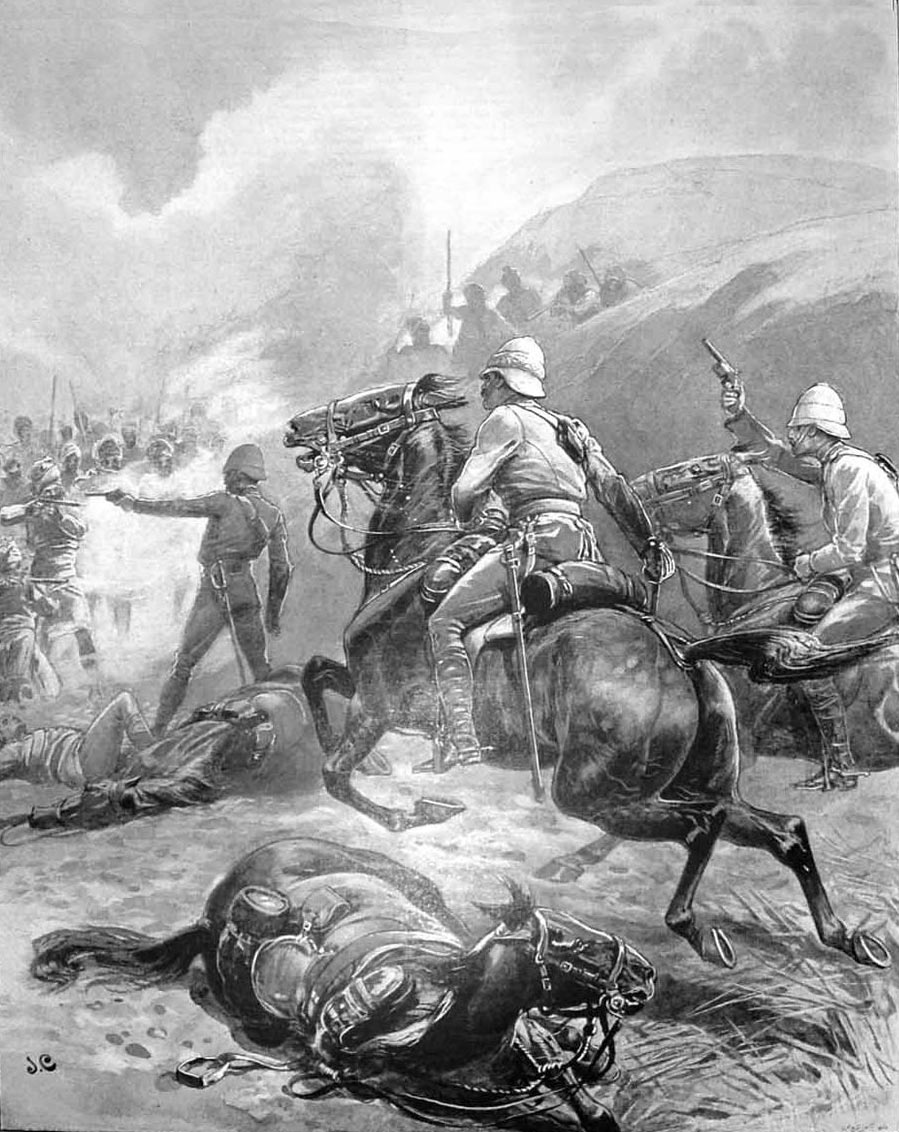

The British 1st Cavalry Brigade, under Colonel Vandeleur, rode the length of the Mahratta line and attacked its left, by the fortified village of Mohaulpore.

Vandeleur’s men drove the Mahratta gunners from their positions and captured the guns, before charging into Mohaulpore itself.

Due to the lack of infantry support, the British cavalry was unable to maintain the position or secure the captured guns and were ordered by Lake to fall back. The brigade commander, Vandeleur, was wounded.

The other two British cavalry brigades attacked the Mahratta line at other points, with much the same result.

Macan’s brigade was confronted by a ravine running from the stream and curling around the front of Laswaree village.

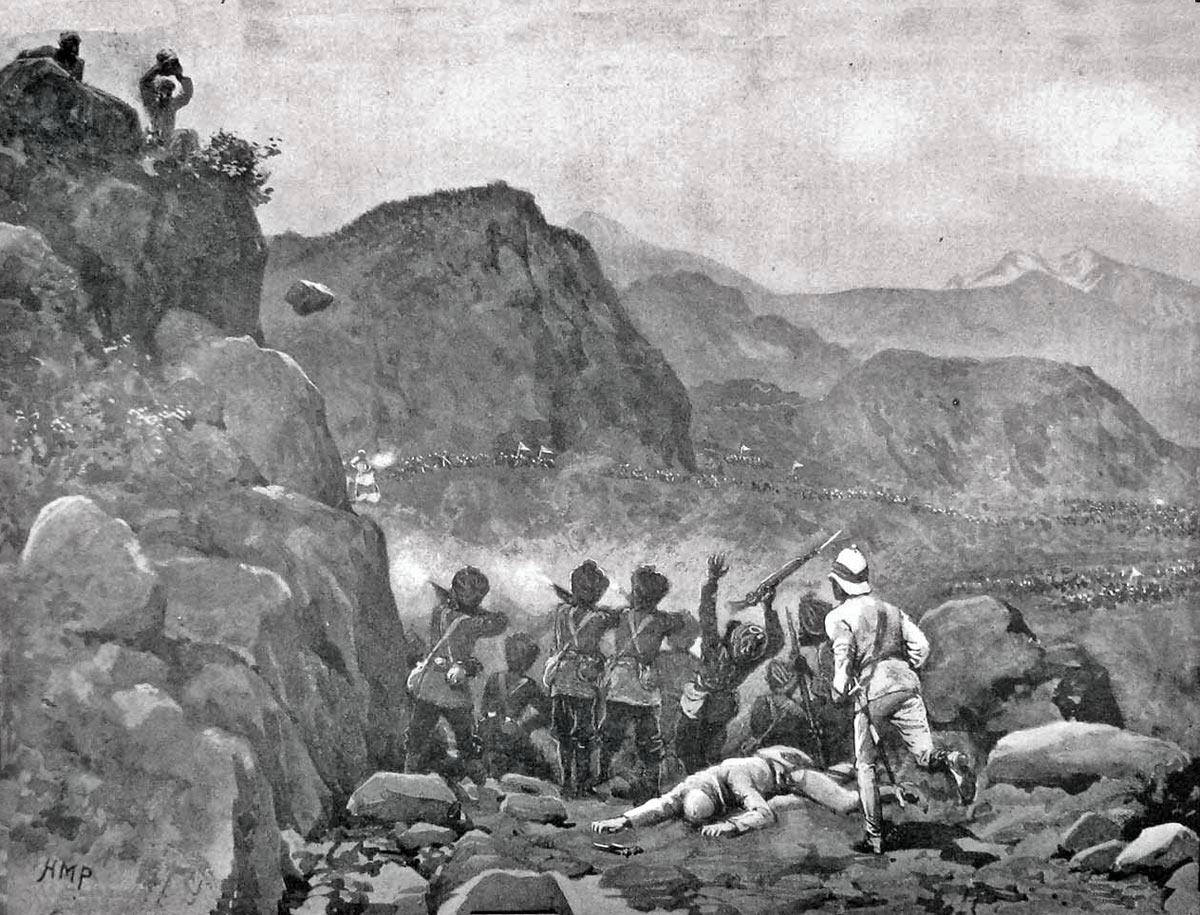

Under a heavy cannon fire, Macan crossed the ravine, formed up and charged the Mahratta line.

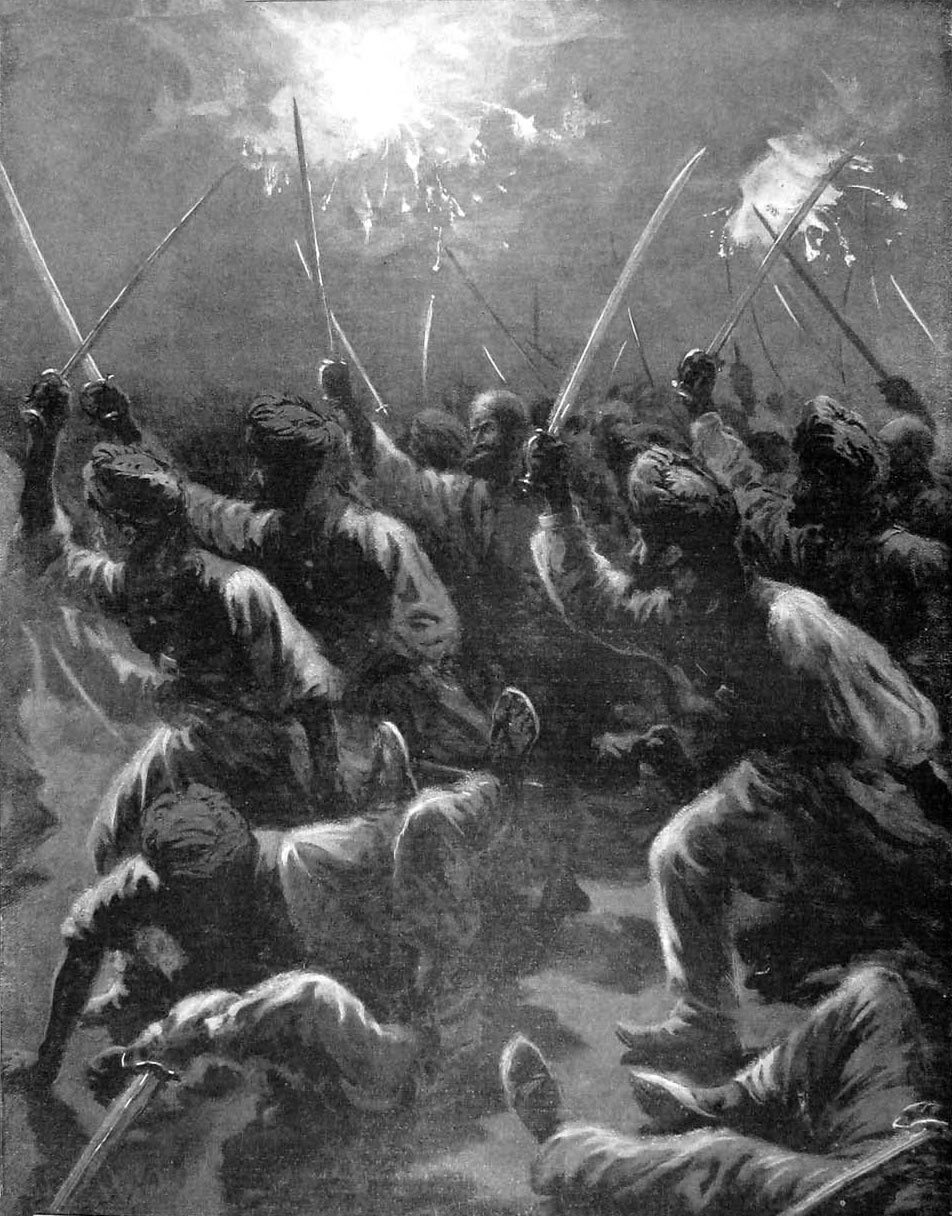

The Mahratta guns, concealed by the long grass and chained together to provide an impenetrable block, held their fire until Macan’s cavalrymen were within 20 yards before discharging a salvo of grape and chain shot.

Macan’s men charged through the gun line and the Mahratta infantry, entrenched behind their waggons and carts, before reforming and charging back through the Mahratta line.

They charged again and were about to carry out a further charge when they were recalled on Lake’s order.

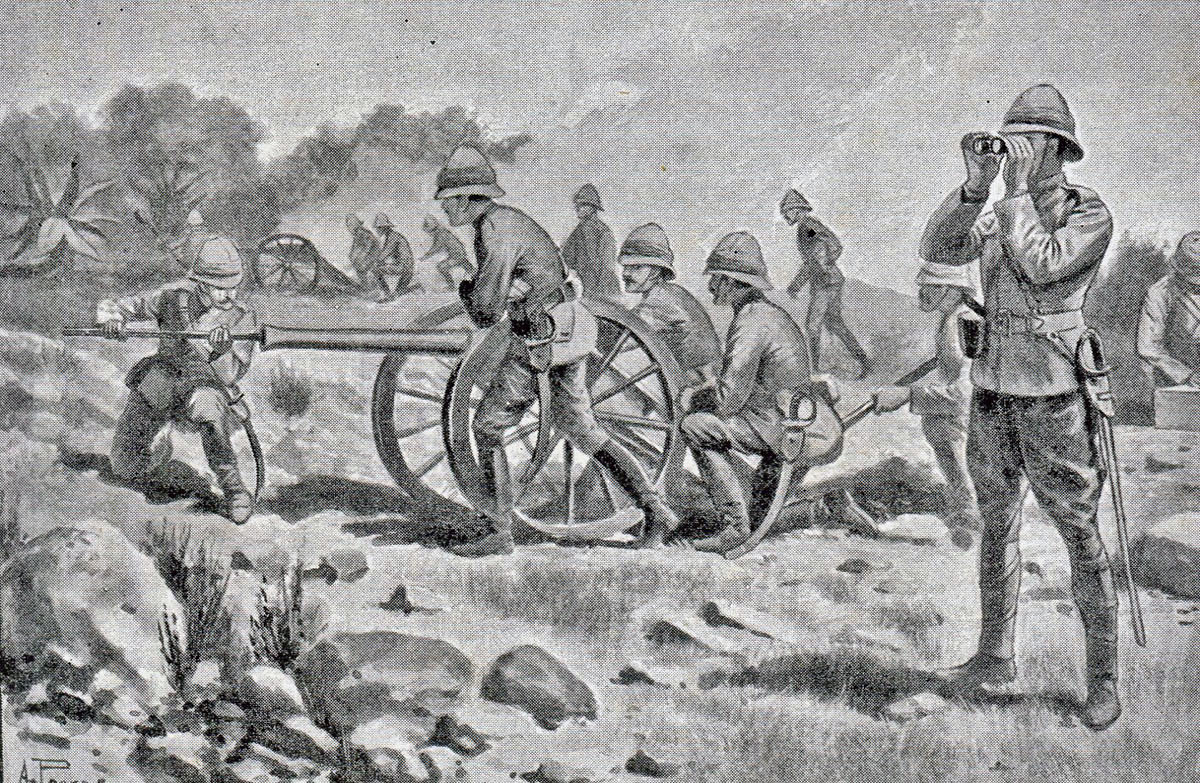

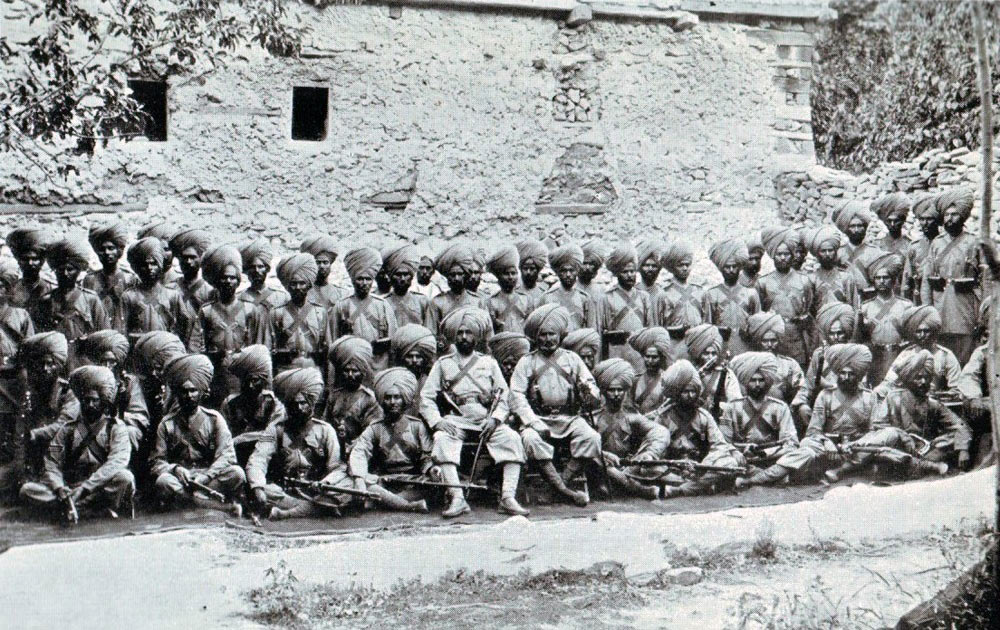

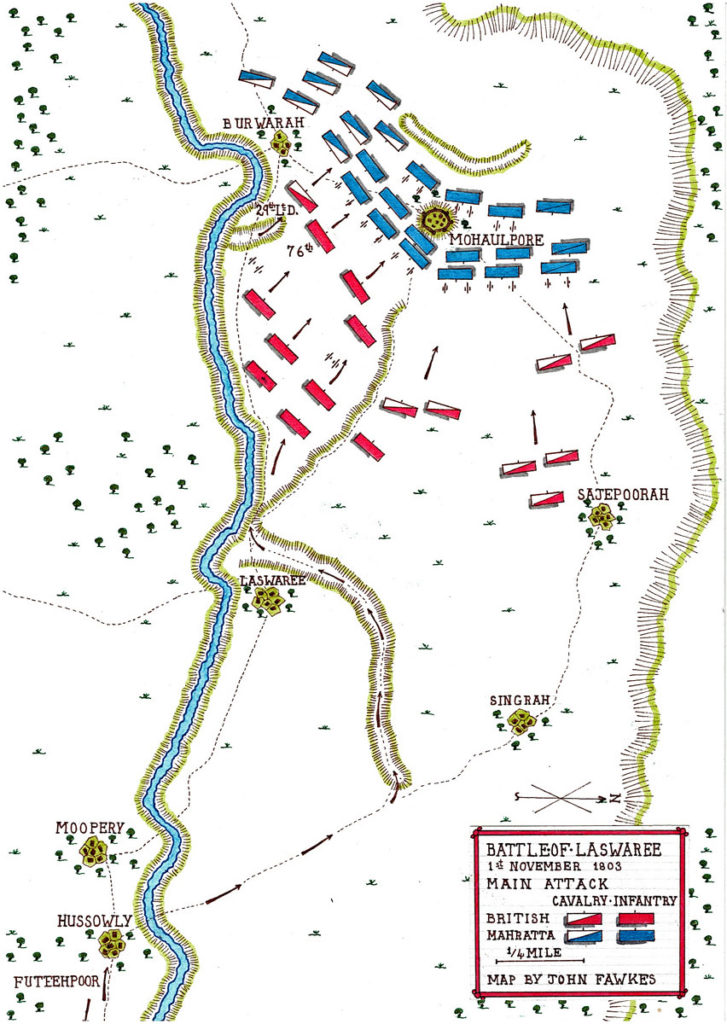

At around 11am, HM 76th Regiment and four battalions of Bengal Native Infantry arrived on the battlefield, exhausted after setting out at 3am.

Lake gave the infantry an hour to recover from the march before making their attack.

In the meantime, a message was received from Abaji stating that he was prepared, subject to certain terms, to surrender his guns.

Lake returned a message accepting Abaji’s proposal and giving him an hour to confirm the agreement.

However, Lake continued to prepare his further attack, while Abaji, far from confirming the agreement, took up a new position with his infantry in front of and behind the fortified village of Mohaulpore and his cavalry between the village and the stream, his powerful artillery positioned along the front of the village.

At the end of the stipulated hour Lake began his attack.

Lake’s infantry advanced along the bank of the stream in column, partially concealed by the long grass.

Macan’s cavalry brigade supported the infantry, while the other two British cavalry brigades advanced around the northern side of Mohaulpore.

Seeing the British column advancing along the stream, Abaji pulled back his right wing, putting his line in an ‘L’ shape.

The British guns opened fire on each end of the Mahratta line, but were easily overborne by the greater number and heavier Mahratta artillery.

HM 76th and two BNI battalions headed the column advancing along the stream and began the attack under heavy cannon fire and with Mahratta cavalry threatening an attack on the left wing of the 76th.

Lake ordered HM 29th Light Dragoons to come up in support of the 76th.

Emerging from the hollow in which they had been waiting, the 29th Light Dragoons formed on the left wing of the 76th and the Mahratta cavalry abandoned their attack and withdrew.

There was then a pause in the battle.

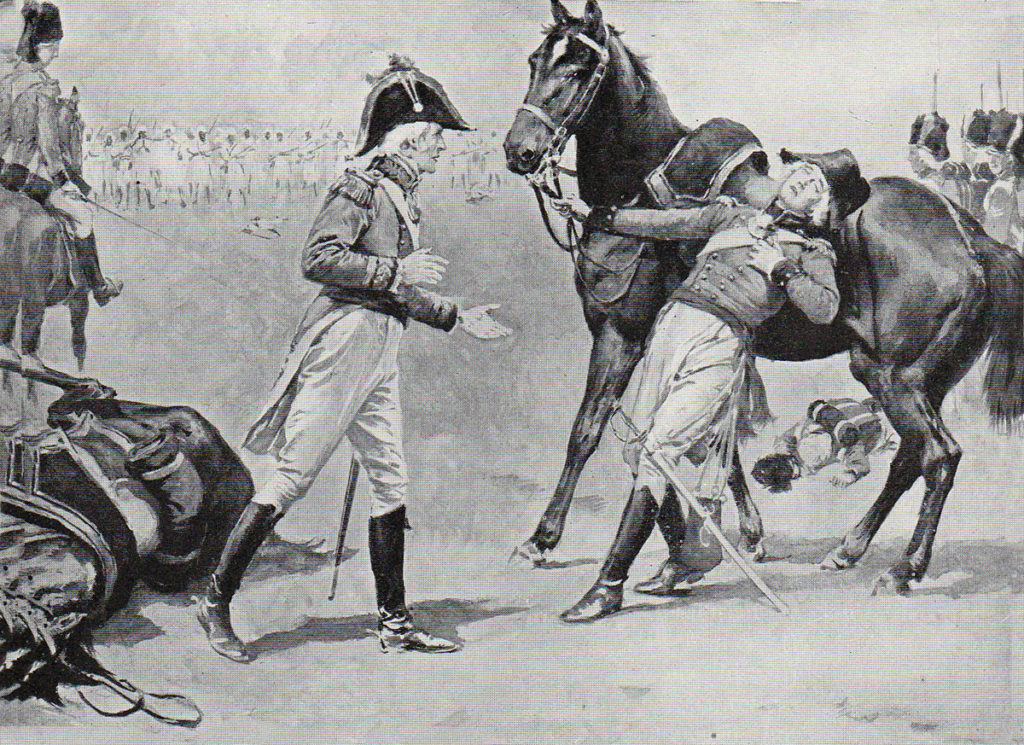

At this point the incident took place in which Lake’s horse was shot and killed under him.

Lake’s son, his ADC, dismounted to give his horse to his father and was struck by a cannon shot and severely wounded.

Lake, in spite of his anguish for his son, mounted the horse and ordered a new attack.

HM 29th Light Dragoons charged through the Mahratta gun line and then the infantry line, before wheeling and attacking the Mahratta cavalry.

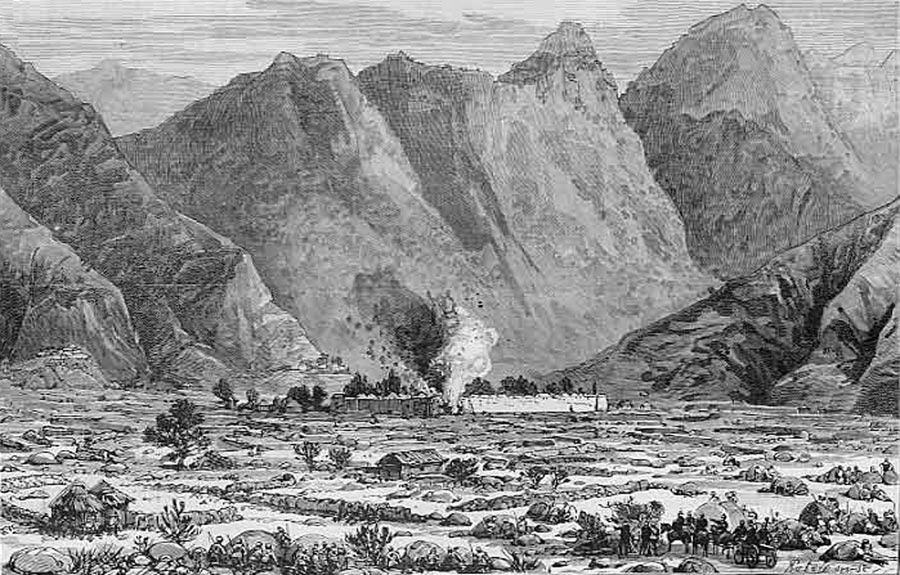

Lake brought up the infantry, now reinforced by the remaining battalions of Bengal Native Infantry that had caught up, advanced through the guns and the Mahratta infantry, taking the village of Mohaulpore.

Abaji’s second infantry line was driven into the plain where they were attacked by most of Lake’s force.

As the Mahratta column attempted to leave the battlefield, they were charged by the 27th Light Dragoons and the 6th Bengal Native Cavalry of Colonel St Leger’s Second Cavalry Brigade and cut down, only some 2,500 Mahrattas surviving the carnage, to be made prisoner.

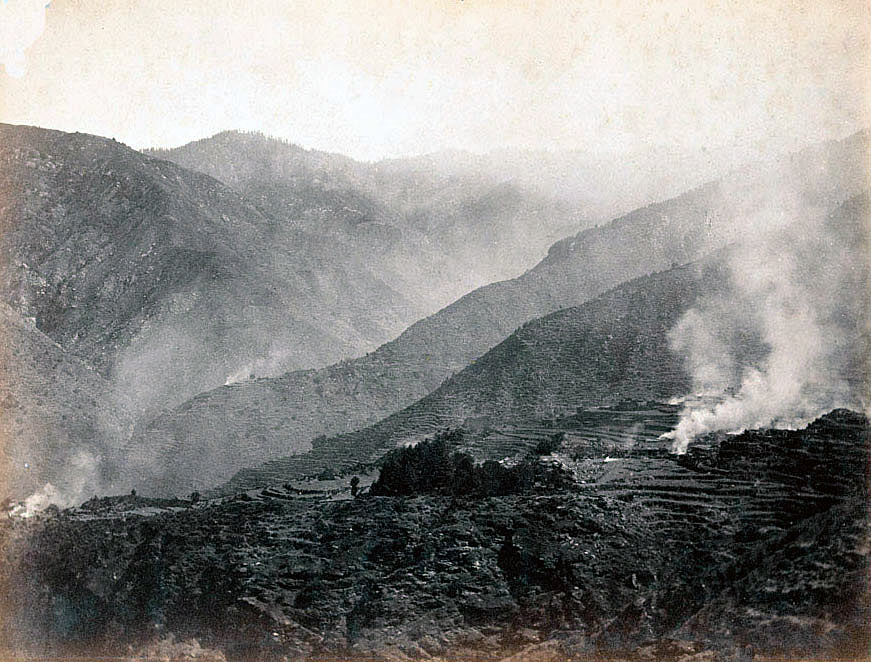

The field was strewn with corpses and wounded soldiers, the remnants of the seventeen sepoy battalions trained by the French officer, De Boigne.

The village of Mohaulpore was a heap of smoking ashes.

Mahratta guns remained chained together in lines with the gunners lying dead and wounded around them.

The remaining guns lay across the battlefield, some overturned, the abandoned slow matches of the gunners periodically detonating the contents of the ammunition tumbrils.

Over the battlefield hung a thick pall of smoke from the detonation of gun powder.

In the evening a bank of clouds built up and a heavy thunderstorm broke.

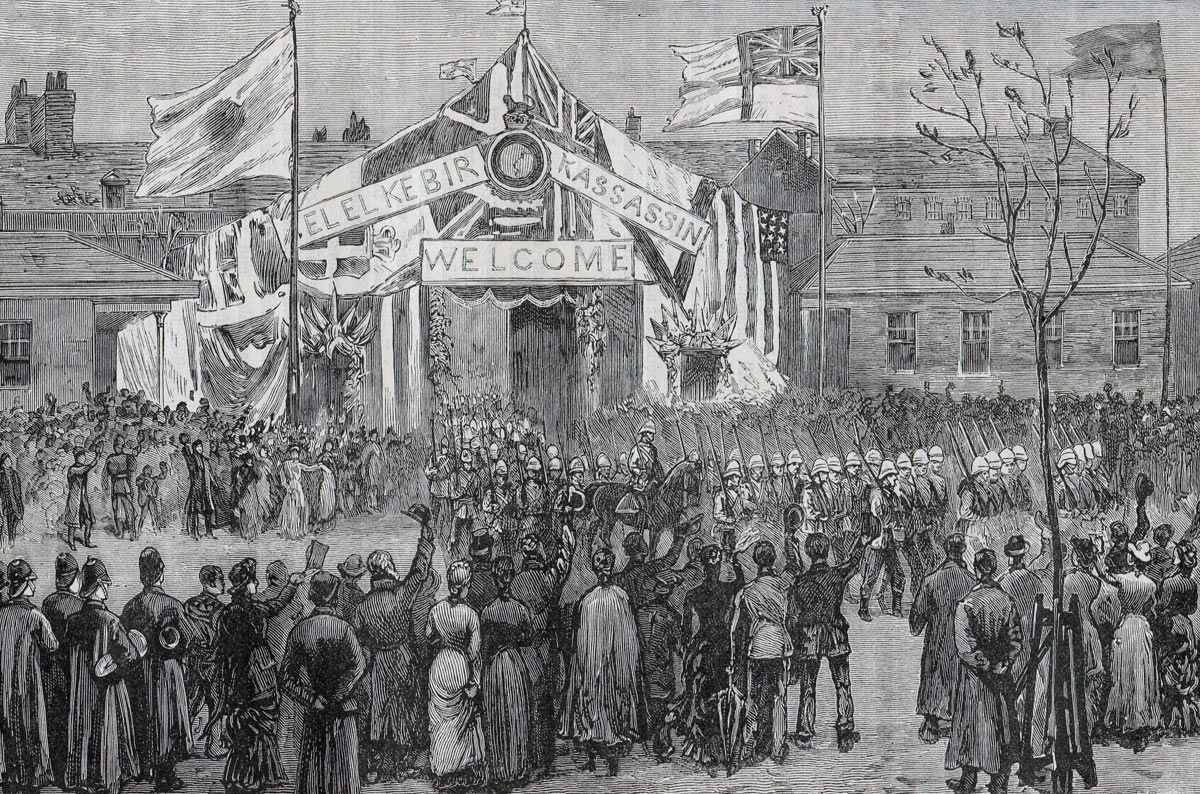

Casualties at the Battle of Laswaree:

In the Battle of Laswaree the British lost 13 officers and 159 soldiers killed and 29 officers and 623 soldiers wounded.

HM 76th Regiment suffered casualties of 43 killed and 149 wounded.

The 76th suffered casualties in the whole campaign, with its three battles, of 18 officers and 428 soldiers killed or wounded.

Casualties in the 3 British cavalry regiments were:

The 8th Light Dragoons suffered 54 casualties and lost 116 horses.

The 27th Light Dragoons suffered 48 casualties and lost 86 horses.

The 29th Light Dragoons suffered 62 casualties and lost 112 horses.

The British Quartermaster General’s deputy and an ADC were killed and the Adjutant General, the Secretary, the Political Agent and the commander of the General’s escort wounded.

Abaji’s Mahratta army was destroyed in the battle with 2,000 soldiers captured.

All 71 of the Mahratta guns were taken by the British.

Follow-up to the Battle of Laswaree:

Lake was forced to remain on the battlefield until 8th November 1803, caring for his wounded, among whom was his son.

On that date Lake marched to a camp outside Agra, sending his wounded and captured guns into the fortress.

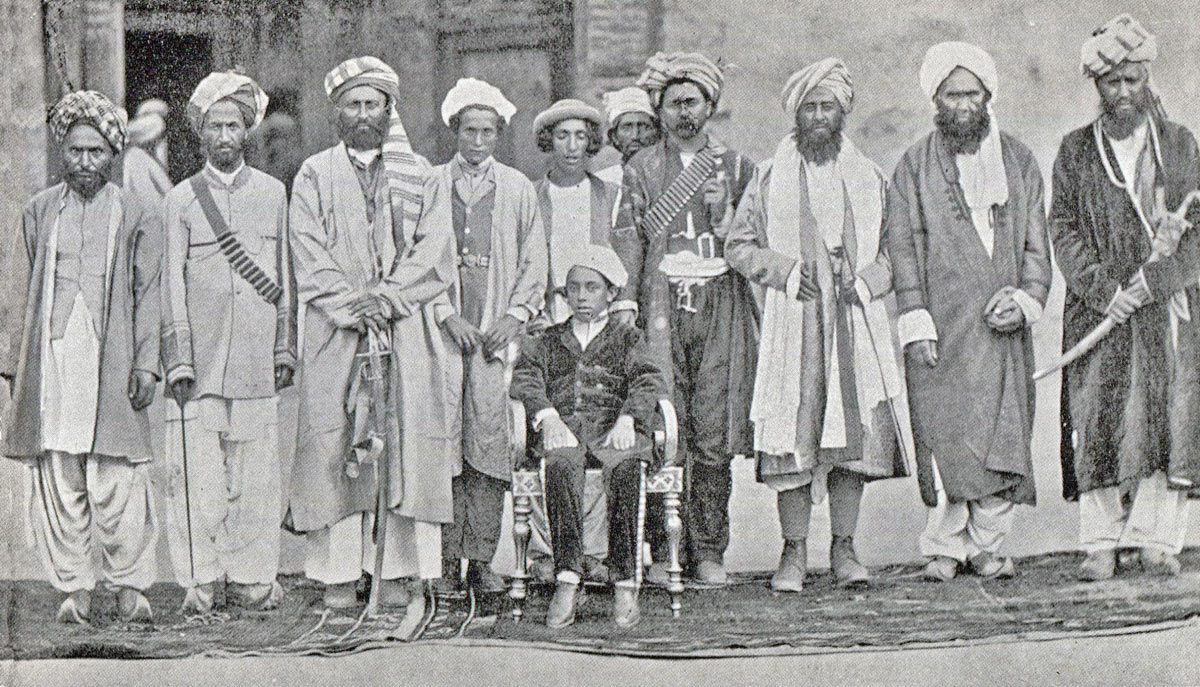

Lake there received the rulers from the area seeking to placate the conqueror of the Mahrattas and to sign defensive alliances with him.

The Battle of Laswaree was a significant milestone in the rise of British power in India.

On 29th August 1803 a British force captured the fortress of Baroach on the west coast of India north of Bombay and the surrounding district.

On 30th December 1803 Scindia signed a treaty with the East India Company bringing the war to an end.

By the treaty Scindia ceded to the East India Company an expanse of territory between the Ganges and Jumna Rivers and other areas including the district of Baroach.

Battle Honours:

Battle Honours were awarded to the following regiments:

Storming of Aligarh: HM 76th Regiment

Battle of Delhi: HM 76th Regiment and 2nd/15th Bengal Native Infantry

Battle of Laswaree: HM 8th Light Dragoons, HM 76th Regiment, 2nd/9th, 2nd/15th and 2nd/16th Bengal Native Infantry

The other regiments of HM Light Dragoons had been disbanded by the time the Battle Honours were awarded.

HM 76th Regiment was awarded special colours by the East India Company with the Battle Honour ‘Hindoostan’ embroidered in the centre.

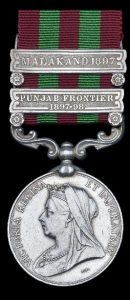

Army of India Medal

The Army of India Medal was issued in 1851 to officers and soldiers of the British and East India Company armies who served at specified battles between 1803 and 1826. The medal was issued to officers and soldiers who fought at the Storming of Aligarh and the Battles of Delhi and Laswaree with the clasps ‘Allighur’, ‘Battle of Delhi’ and ‘Laswarree’.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Laswaree:

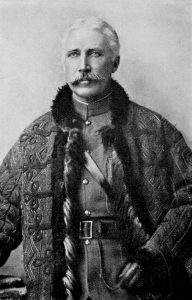

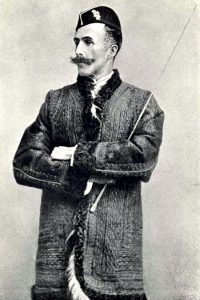

- General Lake was British Commander-in-Chief in India from 1801 to 1807. Lake was made a viscount for his services. He is reputed to have died nearly penniless due to excessive gambling.

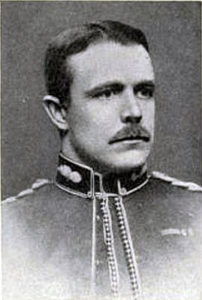

- Lake’s son, Major George Lake, recovered from the wound he received at Laswaree, but was killed commanding the 29th Regiment of Foot at the Battle of Roliça, Portugal on 17th August 1808.

- Lake’s horse, killed under him at the battle of Laswaree, was named ‘Old Port’. Old Port was well known in the Bengal Army and was said to be a favourite of the Viceroy.

- The 76th Regiment was for some years known as the ‘Hindoostan’ Regiment. In the Cardwell reforms of the 1880s the regiment became the 2nd Battalion of the Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment.

References for the Battle of Laswaree:

Fortescue’s History of the British Army.

The Decisive Battles in India by Malleson

The previous battle in the Second Mahratta War is the Battle of Assaye

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Roliça

To the Second Mahratta War index