The unsuccessful English siege of Orléans between October 1428 and May 1429 that saw the dramatic emergence of Joan of Arc and the beginning of the end of the English invasion of France and the Hundred Years War

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Verneuil

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of the Herrings

War: Hundred Years War.

Date of the Siege of Orléans: October 1428 to May 1429

Place of the Siege of Orléans: City of Orléans in central France.

Combatants at the Siege of Orléans: An English and Burgundian army besieged Orléans. The city garrison was led by Dunois, the ‘Bastard of Orléans’ (half-brother of the Duke of Orléans) with a relief operation by the Franco-Scottish army of the Dauphin of France commanded by the Duke d’Alencon with Joan of Arc.

Commanders at the Siege of Orléans : The Earl of Salisbury commanded the English army until his death when the command fell on the Earl of Suffolk.

The French garrison of Orléans was commanded by Dunois, later the Comte de Dunois, half-brother of the Duke of Orléans and known as ‘the Bastard of Orléans’. The relieving French army was commanded by the Comte d’Alençon, inspired and encouraged by Jean d’Arc.

Size of the armies at the Siege of Orléans: The English army numbered around 10,000 men. The Franco-Scottish contingents numbered around 15,000 men.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Siege of Orléans: Knights increasingly wore steel plate armour with visored helmets. Their weapons were lance, shield, sword, various forms of mace or club and dagger. Many carries two-handed swords in battle. Each knight wore his coat of arms on his surcoat and shield.

There were contingents of archers with both the English and Scottish contingents.

The archers carried a powerful bow, capable of many aimed shots a minute.

For hand-to-hand combat archers carried swords, daggers, hatchets and war hammers. They wore jackets and loose hose. Archers’ headgear was a skull cap either of boiled leather or wickerwork ribbed with a steel frame.

The Lombard knights that fought for the French are reported as riding ‘barded’ horses: that is horses in ‘horse armour’: the reason, it is claimed, for their being enabled to overwhelm the archers of the English reserve.

Horses were particularly vulnerable to arrows and, it is said, that the Lombards’ ‘barding’ enabled their horses to survive the English arrow-discharges.

By the time of the Siege of Orléans, artillery was a well-established weapon of war, particularly in sieges.

The garrison of Orléans possessed many cannon, as did the besieging English army.

Winner of the Siege of Orléans: The English failed to take Orléans, their failure being a significant milestone in the English defeat at the end of the Hundred Years War.

Events leading to the Siege of Orléans:

In 1428, the English with their Burgundian allies controlled Paris and much of Northern France.

The Dauphin, the mainspring of French resistance to the invading English, ruled France south of the River Loire, from his de facto capital, the city of Bourges.

In mid-1428, the English regent and military commander, the Duke of Bedford, resolved to capture the City of Orléans.

Orléans lies mid-way between Paris and Bourges and is an important crossing point on the River Loire, the northern boundary of the Dauphin’s territory.

With Orléans in English hands, Bedford planned to move against the Dauphin.

In late August 1428, an English army led by the Earl of Salisbury captured the City of Chartres and marched south-east towards Orléans, taking a number of towns on the way.

The final capture was of Janville, a town fifteen miles north of Orléans, which Salisbury made his advanced base for the attack on Orléans.

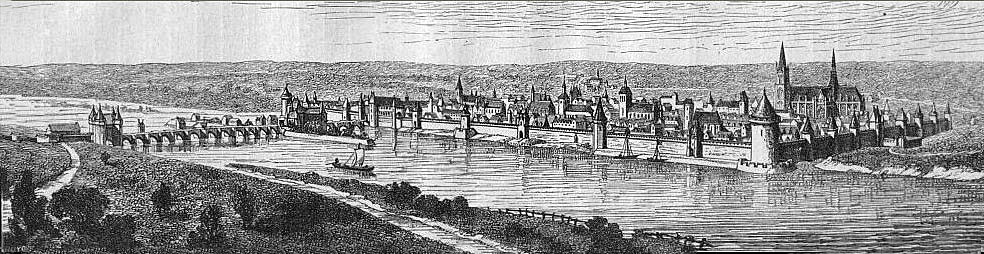

Orléans lies on the River Loire, a major commercial artery crossing the centre of France.

Salisbury’s next step was to capture the towns on the River Loire above and below Orléans, to cut off the city’s access to supplies brought in by boat.

On 8th September 1428, English artillery passed close to Orléans on its way to the first of these towns, Meung on the north bank of the River Loire, 12 miles below Orléans.

Meung surrendered to Salisbury, enabling his army to move west to Beaugency, 20 miles from Orléans, also on the north bank of the River Loire.

Beaugency surrendered on 16th September 1428, following successful English attacks on the north and south banks, use being made of the bridge across the River Loire at Meung to approach Beaugency along the south bank.

On 2nd October 1428, an English force commanded by Sir William de la Pole, brother of the Earl of Suffolk, marched past Orléans and invested the town of Jargeau, 12 miles upstream from Orléans on the River Loire.

Jargeau surrendered to de la Pole on 5th October 1428.

De la Pole marched on to take the town of Châteauneuf, before turning back to Orléans itself.

Account of the Siege of Orléans:

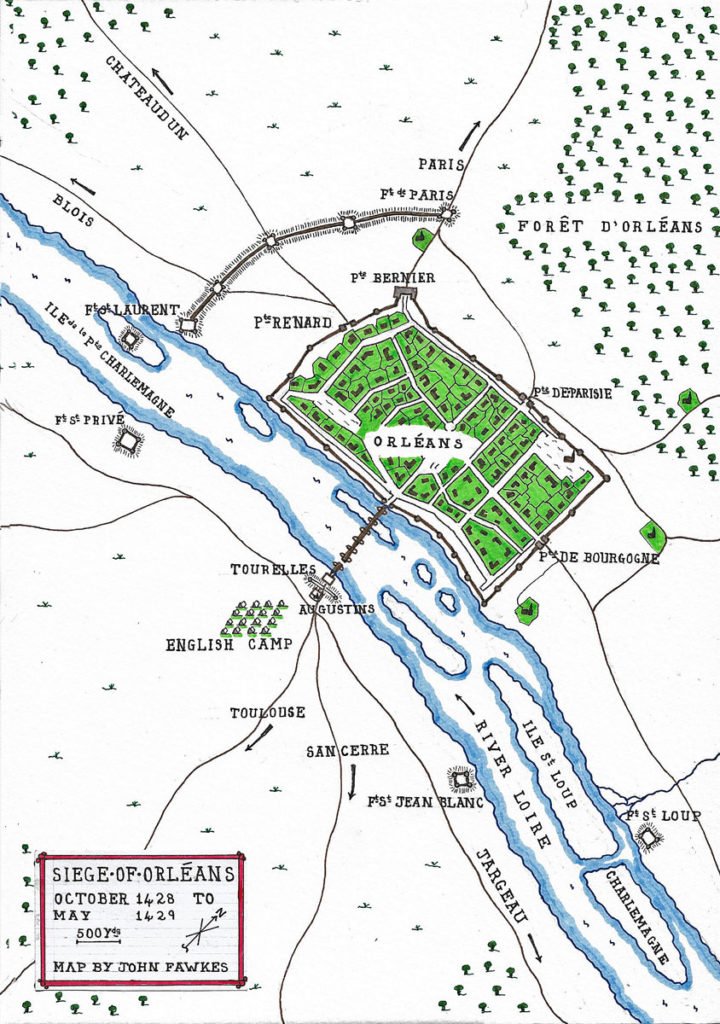

The City of Orléans lay on the north bank of the River Loire. An imposing bridge connected the city to the south bank, from where roads led to the south and south-east of France.

De la Pole marched his force along the south bank of the Loire to the city, arriving at Orléans on 7th October 1428 and beginning the siege.

On 12th October 1428, De la Pole was joined by the Earl of Salisbury with the main English army, encamping in the suburb of Olivet, on the southern side of the River Loire, where they were later joined by 1,500 Burgundians.

The authorities in Orléans had been expecting to be attacked for some years and considerable resources had been devoted to improving the city’s defences, laying in stores and establishing a powerful defensive artillery.

The city walls were strong, high and in good order. There were five powerfully defended gates.

The full-time garrison comprised 2,400 troops with a further 3,000 armed city inhabitants in support, all commanded by Dunois, ‘the Bastard of Orléans’.

As it passed Orléans, the River Loire was 400 yards wide, shallow and rapid with several islands.

The bridge crossing from the city to the south bank of the River Loire comprised 19 arches. On the most southern arch was a fort called ‘Les Tourelles’ with a drawbridge.

On the south bank the garrison had built an extensive earth-work guarding the bridge.

The attack on Les Tourelles:

Salisbury began the attack on Orléans with a heavy artillery bombardment of Les Tourelles.

After two days of the bombardment, Salisbury launched an assault on the earthwork. The garrison repelled the assault.

The English army included a strong force of miners, who set to work digging tunnels under the earthwork.

This caused the French garrison to withdraw from both the earth-work and Les Tourelles onto the bridge, breaking down the two southernmost bridge arches in their rear.

The English repaired Les Tourelles and established a garrison.

The main point of the siege became the bridge, where the English in Les Tourelles confronted the French garrison holding positions further along the bridge.

Each side deployed artillery on the bridge.

On 27th October 1428, Salisbury was in Les Tourelles conducting a reconnaissance of the French defences.

It was the midday ‘stand-down’ for the French cannoneers. It is reputed that the son of one of the cannoneers, on his own in the chamber, fired a cannon.

The Earl of Salisbury and his companions heard the approaching cannon ball and took what cover they could, but the projectile struck the wall of Les Tourelles causing a section of masonry to fly off, severely injuring the Earl of Salisbury in the face.

Salisbury was carried to Meung, where he died on 3rd November 1428.

With Salisbury’s death, command of the English and Burgundian army fell on the Earl of Suffolk.

Suffolk lacked Salisbury’s aggressive temperament and, instead of launching a full assault on Orléans as Salisbury clearly planned, he moved his army into winter quarters in the surrounding towns.

Suffolk left Sir William Glasdale with a small force to hold Les Tourelles and the fortifications in its rear.

The French garrison, in the meantime, received reinforcements commanded by the Comte de Dunois, the Bastard of Orléans, who took over command of the garrison.

In December 1428, the arrival of John Lord Talbot, a senior commander of resource and determination, caused the English to resume the active siege.

The attack on Orléans continued by way of mining and bombardment of the walls.

The walls around Orléans were nearly 1 ¼ miles in length, too long to be fully surrounded by the small English/Burgundian army.

The attack was concentrated on the western face of the city. A main camp was set up at St Laurent, with a post on the Petit Isle de Charlemagne linking up with the troops assaulting from Les Tourelles at the southern end of the bridge.

A line of forts linked by a fence and ditch was built from St Laurent around the western flank of the city’s defences.

A further fort was built at St Loup on the riverbank to the east of Orléans.

These works took until April 1429 to complete.

In the meantime, supplies were brought into Orléans by the roads to the north and north-east of the city.

An attempt was made to build fortified posts to interfere with these supplies, but in April 1429 when the Burgundian force left the army, there were insufficient troops to occupy these posts and they were abandoned.

In the meantime, supplies were brought into Orléans by the roads to the north and north-east of the city.

An attempt was made to build fortified posts to interfere with these supplies, but in April 1429 when the Burgundian force left the army, there were insufficient troops to occupy these posts and they were abandoned.

In February 1429, a convoy of 300 waggons left Paris carrying supplies for the English army besieging Orléans.

A principal component of the cargo was a supply of herrings to be eaten in the season of Lent.

The convoy was escorted by 1,000 mounted archers and mounted men-at-arms commanded by Sir John Fastolf.

On 11th February 1429, the herring convoy reached the town of Rouvray.

The next morning the convoy left Rouvray heading towards Orléans, when mounted French troops were seen to the south-west.

The men were from a force commanded by the Comte de Clermont.

Clermont attacked Fastolf’s convoy in the Battle of the Herrings and was heavily defeated.

The army led by Clermont was the force assembled to relieve Orléans. Any prospect of lifting the siege was lost for the time being.

Dunois and his men managed to evade Fastolf’s force and escape back into Orléans.

In March 1429, Dunois sent a deputation of prominent citizens to Paris with an offer that Orléans surrender and become an open city, giving the English and Burgundians access to the country south of the Loire.

The Duke of Burgundy was keen to take up the offer, but the Duke of Bedford, believing that Orléans was near to being taken by the English, refused the offer.

Irritated by Bedford’s refusal of Dunois’ proposal, Philip of Burgundy withdrew the Burgundian troops from the army besieging Orléans.

Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc):

Jeanne d’Arc or Joan la Pucelle (Joan the Maid) came from the village of Domrèmy on the eastern border of France.

Inspired by dreams that it was the divine wish that the English be expelled from France and that the Dauphin be crowned King Charles VII, Joan made her way to the Castle of Chinon where she persuaded the Dauphin to launch a further attempt to relieve Orléans.

On 17th April 1429, an army of some 4,000 men-at-arms commanded by the Duc d’Alençon, accompanied by Joan of Arc, set out from Blois for the relief of Orléans.

The presence of Joan of Arc transformed the morale of the French soldiers, previously intimidated by the reputation of the English armies.

The French rank and file accepted and largely obeyed the religious strictures laid down by Joan of Arc: no swearing, no loose women in the camps, all to attend mass and make confession.

A body of priests headed the French army as it advanced to the relief of Orléans.

A significant role of d’Alençon’s army was to resupply the garrison and population of Orléans.

The plan adopted by Dunois and d’Alençon, in regular communication, was for the relieving army to send the supplies along the south bank to the upstream town of Chézy, while the numerous barges moored along the waterfront of Orléans sailed up the river to Chézy.

At Chézy, the supplies were loaded onto the barges which sailed back to Orléans, the supplies being landed to the east of the city and brought in through the Porte de Bourgogne.

As a distraction, Dunois arranged a diversionary attack on the English garrison of Fort St Loup, to the east of the Porte de Bourgogne.

Joan of Arc entered Orléans on 30th April 1429 to the clamorous welcome of the inhabitants.

D’Alençon’s army remained on the south bank of the River Loire and returned to Blois, bringing up a second supply convoy. This time taking the route from Blois along the north bank of the River Loire, entering Orléans on 3rd May 1429.

On 4th May 1429, the garrison attacked the English garrison in Fort St Loup. The attack was intended as a feint, but Joan of Arc joined the attack and so inspired the assaulting force that they overcame the defences and captured the fort.

Talbot attempted to relieve Fort St Loup but, marching around the city from Fort St Laurent, was intercepted by a force from Orléans which held him off until it was too late to prevent the fort’s capture.

On 6th May 1429, the French launched an attack on the English garrison in Les Tourelles.

The attacking French force is reported to have numbered more than 4,000 men, while the English garrison in Les Tourelles and the earthworks was around 500.

After two days’ fighting, the English garrison in Les Tourelles and the neighbouring fortifications were compelled to surrender.

There was now no prospect for the English of taking Orléans.

On 8th May 1429 the English army formed up in the ground outside the city fortifications, challenging the French to open battle.

The challenge was not taken up, the French remaining inside Orléans.

The English army marched off to the north, abandoning the abortive siege. There was no pursuit.

Casualties at the Siege of Orléans:

French casualties at the ‘Battle of the Herrings’ were around 120 knights and 600 men-at-arms killed, among them Stewart of Darnley and one of his sons.

English casualties at the ‘Battle of the Herrings’ were light.

Casualties on either side in the whole siege are unknown.

References for the Siege of Orléans:

Cursed Kings, Volume IV of the four-volume record of the Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption.

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman.

The Hundred Years War by Burne

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Verneuil

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of the Herrings