The English siege of Calais between 4th September 1346 and 3rd August 1347 in the Hundred Years War and its capture leading to an English occupation of the town for 200 years

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Creçy

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Neville’s Cross

War: Hundred Years War.

Date of the Siege of Calais: 4th September 1346 to 3rd August 1347

Place of the Siege of Calais: on the north-east coast of France on the English Channel.

Combatants at the Siege of Calais: An English army besieged a French garrison.

Commanders at the Siege of Calais: King Edward III commanded the besieging English army.

The French garrison was commanded by Jean de Vienne, a Burgundian knight and Enguerrand de Beaulo.

Command was later assumed by Jean de Fosseux, a lieutenant-governor of Artois.

Size of the armies at the Siege of Calais: The English army numbered around 10,000 to 12,000 men, after the arrival of reinforcements from England.

They were later reinforced by an army of around 20,000 Flemings.

The French garrison numbered around 6,000 men.

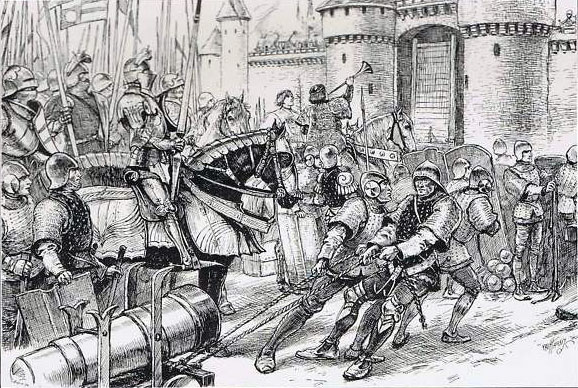

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Siege of Calais: Knights increasingly wore steel plate armour with visored helmets. Their weapons were lance, shield, sword, various forms of mace or club and dagger. Many carried two-handed swords in battle. Each knight wore his coat of arms on his surcoat and shield.

The archers carried a powerful bow, capable of many aimed shots a minute.

For hand-to-hand combat archers carried swords, daggers, hatchets and war hammers. They wore jackets and loose hose. Archers’ headgear was a skull cap either of boiled leather or wickerwork ribbed with a steel frame.

By the time of the Siege of Calais, artillery was a well-established weapon of war, particularly in sieges.

Winner of the Siege of Calais: Calais surrendered to the English in September 1347.

Events leading to the Siege of Calais:

King Edward III of England sailed from Portsmouth on 28th June 1346 to begin his invasion of France.

The English fleet anchored off the coast of the Cherbourg Peninsula on 12th July 1346 and after taking and plundering the local towns Edward’s army began its march to the east.

The English took the town of Caen on 26th July 1346 and continued their march to the River Seine.

The various battles along the route caused significant casualties to the English army and Edward was in need of a reinforcement from England, particularly of archers.

The English needed to capture a harbour to enable their fleet to land the reinforcements. The port of Le Crotoy on the River Seine estuary was selected and additional troops landed there.

In August 1346, a Flemish army with a small English contingent, commanded by the Englishman, Sir Hugh Hastings, invaded France from the north-east and advanced towards Calais.

Edward marched to the River Seine, where desultory negotiations took place with King Philip VI of France, who was in Rouen, through the two cardinals sent by the Pope in Avignon to attempt to bring peace between France and England.

Philip offered to return the parts of Aquitaine held by the French to Edward but subject to the overall sovereignty of the French Crown, the habitual sticking point in such negotiations. Edward rejected the offer and continued his march.

After coming within 20 miles of Paris, Edward withdrew to the coast, followed by Philip VI’s army.

Edward forced a crossing over the River Seine and on 26th August 1346 fought the Battle of Creçy against King Philip’s pursuing and much stronger army.

The French army was decisively beaten by the English and suffered terrible casualties, notably among the French nobility.

In early September 1346, Edward resolved to capture Calais and use it as the port of contact with England instead of any of the Normandy ports as he had originally planned.

The distance between Calais and England was shorter and Calais was nearer to Edward’s most consistent and powerful allies, the Flemish.

Account of the Siege of Calais:

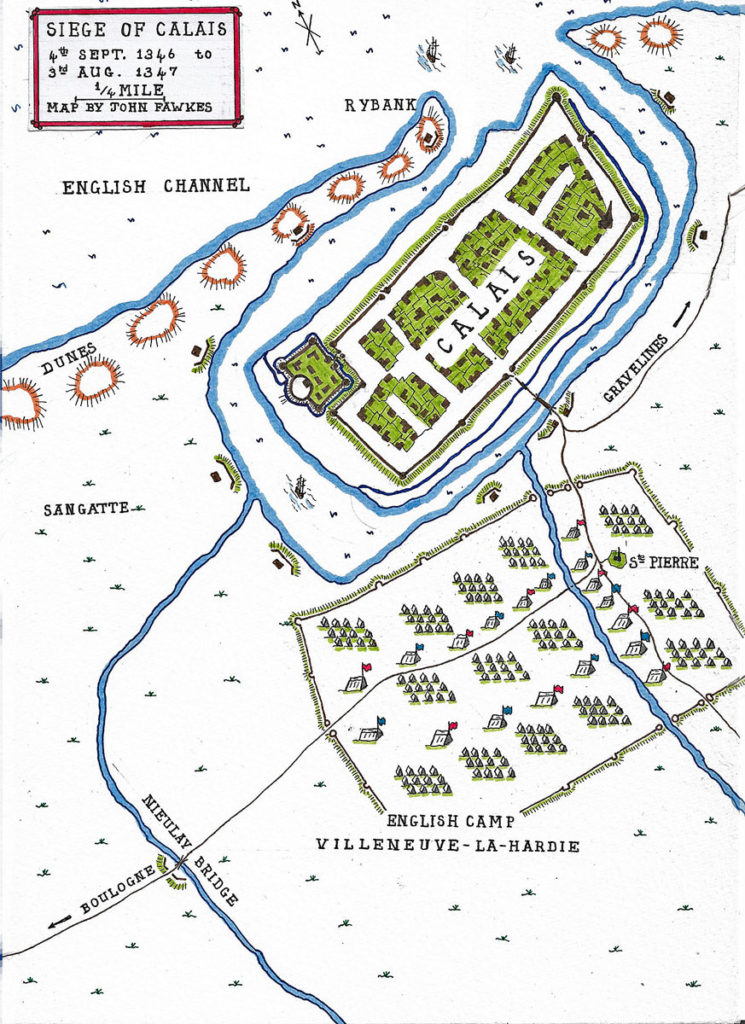

The City of Calais, a minor port in the French county of Artois, lies on the English Channel coast within a few miles of the border with Flanders.

The harbour was heavily silted and not particularly satisfactory causing the regular cross-Channel traffic to use larger and better harbours further along the French coast to the south-west.

Calais’ position near the Flemish border was the key factor for King Edward in his decision to capture the town and occupy it as England’s main base for its incursion into Northern France.

Calais lay in a large expanse of marshland, much of it flooded, which made it difficult to attack.

In a siege, the walls of Calais could not be undermined and the garrison could interfere with siege operations by opening sluice gates and flooding the area.

Supplies could be brought in for the garrison by sea and unloaded in the port.

An effective siege required a substantial army and a supporting fleet to prevent the arrival of supplies by sea.

The French garrison in Calais was initially commanded by Jean de Vienne, a Burgundian knight and a local knight, Enguerrand de Beaulo.

On 14th August 1346 Jean de Fosseux, a lieutenant-governor of Artois, arrived in Calais to take command.

The position of Calais, in the middle of an extensive marshland with the sea washing around the outskirts, made an attack on its walls difficult and hazardous.

The English settled in for a long siege of the town.

The English built field works around the three land-ward sides of Calais.

At the end of the causeway leading to the main gate in the south wall of the town, the English set up an extensive camp, described as a temporary town.

Supplies for the English camp were brought in from Gravelines or from England by sea.

The English camp was given the name of ‘Villeneuve-la-Hardie’.

Following the Battle of Creçy, the French King Philip VI did not believe that King Edward would attempt to capture Calais, expecting the English army to continue its march on into Flanders.

The English siege of Calais began on 4th September 1346 and King Edward began to set up the arrangements to support and re-supply his army over a protracted period of siege.

On 5th September 1346 the French king, unaware of the English actions, ordered the remains of his army to disperse, thereby losing the instrument he needed to relieve Calais.

On 17th September 1346 the squadron of Genoese galleys in the French service captured and destroyed an English fleet of 25 supply ships on its way to Calais, making the re-supply of the English army more difficult and significantly more expensive.

The French attempted to assemble an army at Compiègne for the relief of Calais, giving 1st October 1346 as the date for the troops to be ready.

Few French troops turned up by the set date.

The war was going badly for the French king. The English and Gascons under the Earl of Lancaster had overrun large parts of western France during 1346, as King Edward III had done in Brittany and Normandy and the Flemings in Northern France. Confidence in the French government was low. Leading to a reluctance on the part of the French to pay taxes or to turn out to fight other than for local defence.

King Philip VI continued to mishandle the war.

The King and his military leaders were wrongly under the impression that the Earl of Lancaster was marching north from Aquitaine and French troops gathering at Compiègne for the relief of Calais were diverted to Orleans.

By the end of October 1346, the French army at Compiègne numbered only around 3,000.

Together with the troops at Orleans and in the various garrisons of the north there were only some 10,000 French troops under arms.

The French Royal Treasury did not have the funds even to pay this small force.

With his attempt to start negotiations with King Edward III, the French king on 27th October 1346 in order to save money ordered his army at Compiègne to disperse.

In addition, the Genoese galley fleet was laid up at Abbeville on the Seine estuary on 31st October 1346.

In the misconceived belief that his lack of funds was due to dishonesty on the part of his civil servants, King Philip VI’s financial councillors were dismissed and the senior councillor was arrested and charged with embezzlement.

Rigorous efforts were made to put France’s public finances on a sounder footing.

Over the winter of 1346/7 there was little military activity around Calais. Supplies for both the garrison and the besiegers continued to arrive without difficulty.

From November 1346 to 27th February 1347 the English made repeated attacks on the walls of Calais, using small fishing vessels to cross the wide moat. All failed.

With the Spring of 1347 it became easier for the English to bring supplies across the Channel.

The French were unable to interrupt these movements.

The squadron of Genoese galleys went home, apparently upset at the treatment of their countrymen at the Battle of Creçy.

Two large French convoys reached Calais, one from Dieppe of 20 ships in mid-March 1347 and one from St Valery of 30 ships in early April 1347.

King Philip VI ordered a new army to assemble for the relief Calais.

King Philip took the Oriflamme at Saint-Denis on 18th March 1347 and marched north. He found that few soldiers had arrived: the dismal response caused by the French Crown’s loss of authority following the defeat at the Battle of Creçy.

Following the battle, a number of French noblemen, suffering from debt and disillusioned with the Valois dynasty and King Philip VI, had even entered into treasonous negotiations with the English King.

In one episode a group of Burgundian noblemen, with English finance, began a revolt against the Duke of Burgundy in November 1346, preventing the duke from sending troops to the King’s army in Compiègne.

In the spring and summer of 1347 forces loyal to the French king attacked Flanders to prevent the Flemings from coming to the assistance of the English attacking Calais and to cut off supplies from the English army.

Edward provided support to the Flemings.

In April 1347, the English succeeded in surrounding Calais with the capture of the Rysbank, a spit of land at the entrance to the Calais harbour on the seaward side.

The English built a fortification on the tip of the Rysbank with artillery to fire on approaching French ships and into the town.

Some 80 English ships arrived and were placed under the command of the Earl of Warwick. Calais was now completely isolated.

After attempts to come to the relief of Calais from the north-east, King Philip VI was persuaded by his advisers to approach the town from Arras in the south, marching in June 1347 to the town of Hesdin, 50 miles to the south of Calais.

In late June 1347 King Philip VI received news of the disastrous defeat and capture by the English of Charles of Blois at the Battle of La Roche-Derien in Brittany, seriously undermining the French position in the Duchy.

Charles of Blois was the French King’s candidate in the civil war between the rival claimants to the dukedom and he was now an English prisoner together with all the important noblemen of the duchy who supported him, who had survived the battle.

King Philip VI was forced to divert troops to Brittany and make arrangements for the government of the Duchy.

In Calais supplies were running out. The inhabitants were reduced to eating dogs, cats and horses and even gnawing the leather of saddles.

Drinking water supplies were very low and disease was taking a hold in the population.

In June 1347 a French fleet of some 40 ships was formed in the mouth of the Seine to force its way into Calais with supplies.

On 25th June 1347 as the French fleet sailed past the mouth of the Seine it was attacked by a larger English fleet, manned by archers and men-at-arms and commanded by the two English admirals and the Earls of Pembroke and Northampton.

The French fleet was scattered and many of the ships went aground.

On the same day Jean de Vienne, the governor of Calais, wrote to King Philip VI informing him that there was nothing left to eat in Calais. He stated that in accordance with the King’s order the garrison would not surrender but would break out of the gates and fight to the death.

This letter was taken out of the town by a Genoese officer, but the officer was captured by the English.

The letter to King Philip VI was read by King Edward who forwarded it to the French king.

A further attempt was made to pass a relief fleet into Calais but this also failed and the ships scattered before reaching the town.

The French garrison then rounded up all useless mouths; old, infirm, wounded, women and children and expelled them from the town.

The besiegers refused to allow these refugees through their lines and they were forced to live under the town walls until they died.

Further reinforcements for the besieging army arrived from England giving King Edward an army of around 5,300 men-at-arms, 6,600 infantry and 20,000 archers, described as the largest army sent overseas from England until the end of the 16th Century.

In addition, there were 15,000 sailors in the fleet and an army of 20,000 Fleming on the nearby border.

The French moved north from Hesdin on 17th July 1347.

Receiving reports from spies in the French camp, the English and Flemish armies concentrated in the siege lines outside Calais.

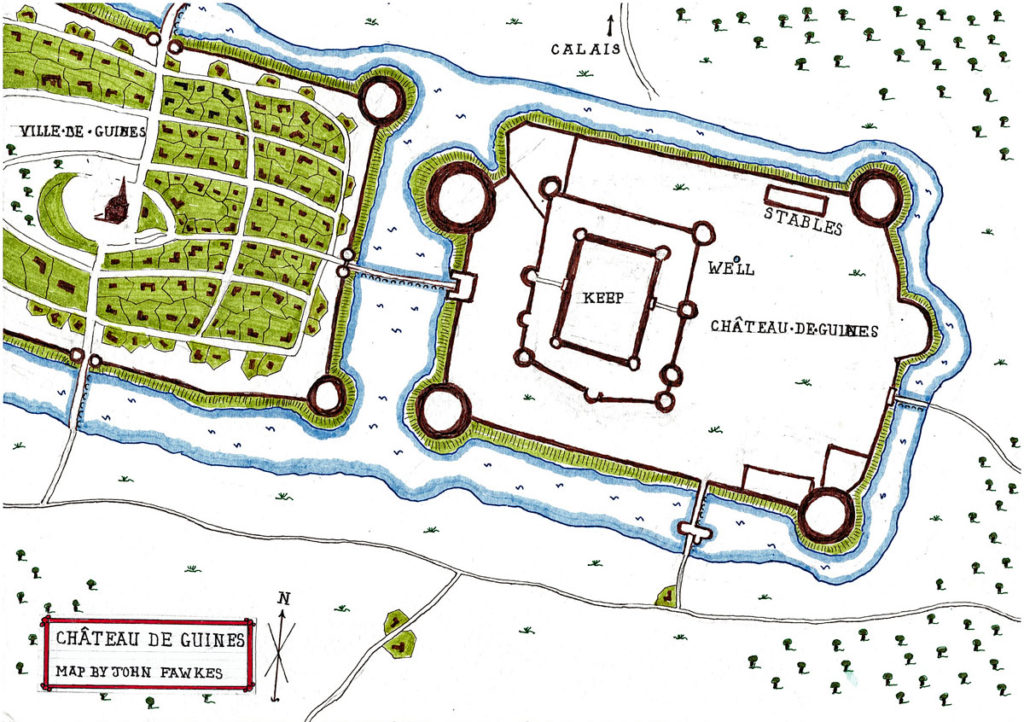

At Saint Omer and then Guines, King Philip’s army was joined by troops from the Flanders border and neighbouring garrisons before advancing to Sangatte.

The French army probably numbered around 20,000 men of whom 11,000 were mounted men-at-arms.

Arriving on the heights of Sangatte the French saw King Edward’s army deployed before them, clearly far outnumbering them.

Protected by the River Ham and obstructions in the coastal area, the only possible route for an attack on the English army was across the Bridge at Nieulay, defended by field works and a powerful garrison.

An attack by the French seemed out of the question.

Philip again resorted to negotiation to try and establish a general peace between France and England, turning to the two cardinals who had time and again attempted to bring the warring sides to an understanding.

In the negotiations it became clear that the French considered Calais to be lost to the English. They only sort to gain the lives and freedom of the garrison and residents of the town.

Philip offered Edward the whole of the Duchy of Aquitaine but to be held as a fief of the French Crown.

These terms had been offered to Edward before the Battle of Creçy and rejected by him. He rejected them again.

The Surrender and the Six Burghers of Calais:

On 1st August 1347 the Calais garrison signalled to the French army on the Heights of Sangatte that they could hold out no longer and intended to surrender.

That night the French army burnt their camp and marched away leaving the Calais garrison to make the best terms they could with Edward.

The Calais commander, Jean de Vienne, met a small group of English knights headed by Walter Mauny outside the town gates.

De Vienne offered to surrender against the lives and liberty of the garrison and residents of the town.

Mauny’s party told Jean de Vienne that Edward would not spare their lives as too much time had been spent on the siege and too many English lives lost. Edward required an unconditional surrender.

But the English knights were uncomfortable in relaying this message. It went against the code of chivalry and their own self-interest. One day they might be at the mercy of the French King and their lives might depend on the fate of the Calais garrison.

Mauny and his companions returned to Edward and made it clear that they were deeply unhappy at his ruthless stance.

In the face of his own army’s opposition King Edward reluctantly agreed to spare the lives of the garrison and residents of Calais, although not their liberty.

In addition, six burgers of the town would have to give themselves up for Edward to deal with as he thought fit. Edward stated: ‘They shall come before me in their shirtsleeves, with nooses round their necks, carrying the keys of the town and they shall be at my mercy to deal with as I please.’

On 3rd August 1357, eleven months after the commencement of the siege, the English army was drawn up outside the gates of Calais with King Edward seated on a dais, accompanied by the Queen, his councillors, allies and commanders.

The six ‘Burghers of Calais’ emerged from the town gate dressed as required and carrying the keys to the town.

They knelt before Edward and begged for mercy.

Wishing to make an example for other towns that might seek to resist him, King Edward called for his executioner and ordered him to behead the six immediately.

The King’s advisers were shocked at his decision and pleaded with him to change his mind.

They were then joined by the Queen who begged the King to spare the men. With an ill grace he agreed to do so and the six were allowed to go free.

The English army entered the town and the inhabitants were rounded up and expelled.

The town was then emptied of the inhabitants’ belongings. These proved to be surprisingly valuable, arising from Calais’ role over the years as a centre for piracy.

The belongings were assembled and distributed across the army.

Jean de Vienne and other senior officers of the garrison and prominent citizens were sent to England to await ransom.

Casualties at the Siege of Calais:

The surviving French garrison became prisoners of war.

There does not appear to be a record of the garrison’s loss during the siege.

Equally there appears to be no record of English losses during the siege. Probably they were high as an unrecorded number of unsuccessful assaults were made on the town walls during the eleven-month siege.

Probably both the garrison and the besieging army suffered significant numbers of deaths from disease during the protracted siege.

Follow-up to the Siege of Calais:

The inhabitants of Calais turned up in the surrounding French towns, largely destitute. King Philip VI was shocked at their fate and decreed that they should be entitled to settle in any French town they chose and that offices of state that became vacant should be made available to them.

A fund was instituted to assist them in the short term.

King Edward III encouraged citizens from England to settle in Calais and make it an English town.

London merchants set up branches in Calais.

Within 3 months of the fall of Calais 200 English people were resident in the town.

Calais remained an English outpost until it was recaptured by the French in the Italian War of 1558, during the reign of Queen Mary of England.

Queen Mary is said to have declared on her deathbed a few months later that they would find ‘Calais’ inscribed on her heart.

References for the Siege of Calais:

Trial by Battle, Volume I of The Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption

The Hundred Years War by Burne

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman.

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Creçy

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Neville’s Cross