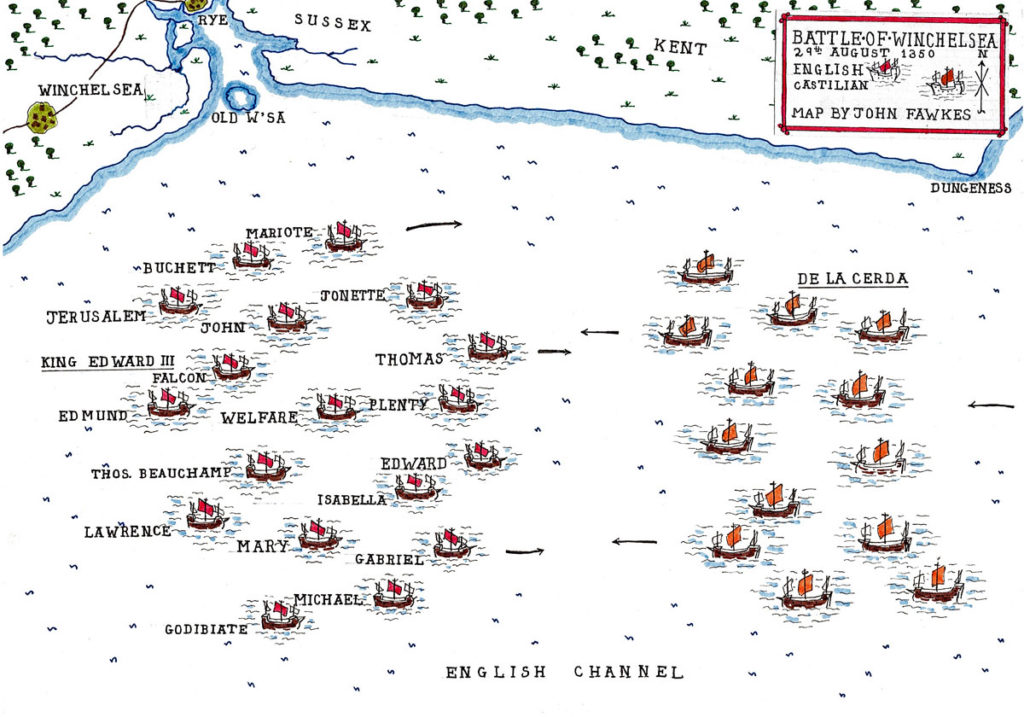

King Edward III’s naval victory over a Castilian fleet commanded by Charles of Spain off the coast of Southern England on 29th August 1350 during the Hundred Years War

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of La Roche-Derien

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Mauron

Date of the Battle of Winchelsea: 29th August 1350.

Place of the Battle of Winchelsea: The battle took place in the English Channel off the English Cinque Port of Winchelsea on the coast of Sussex.

Combatants in the Battle of Winchelsea: An English fleet against a Castilian fleet.

Admirals in the Battle of Winchelsea: King Edward III of England commanded the English fleet. The Castilian fleet was commanded by Charles de la Cerda, Constable of France, known as Charles of Spain.

Size of the navies in the Battle of Winchelsea:

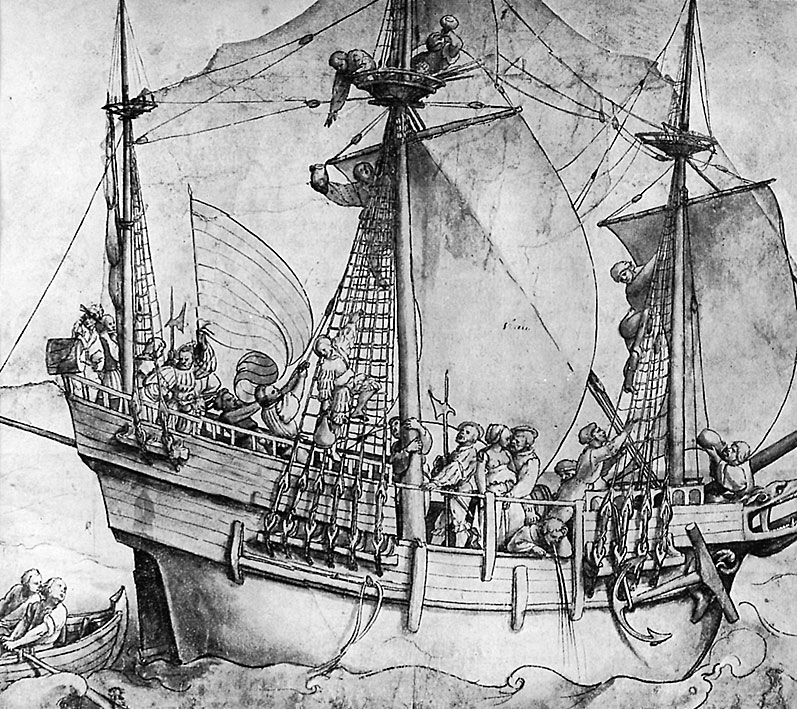

England did not have a dedicated fleet of warships in the 14th Century. In times of war the king called upon the merchant vessels of his subjects and manned them, in addition to their crews, with archers and men-at-arms; converting the ships for war by building forecastles, after castles and crows’ nests, fortifications from which archers directed their fire onto the enemy vessels.

These English merchant vessels were called Cogs; square rigged and single masted with sharp prows and sterns and steered by an oar or a rudder.

The Castilian carracks were significantly larger than most of the English ships, their fighting men being housed in built up structures well above the English fighting platforms, with protective shields against arrows.

The nearest to a formal English navy was the arrangement the King had with the Kentish towns known as the Cinque Ports. In return for trading privileges, the Cinque Ports provided a number of vessels for a period each year for royal military purposes.

Each ship would serve with its regular captain and crew, or, if that crew was not available with a crew of pressed or recruited seamen. The fighting force for each ship comprised men-at-arms and archers otherwise employed as soldiers on land.

Command of each ship would be exercised by a senior knight or nobleman.

Such a system seems to have prevailed in the ships of most European nations.

In battle, a ship would lay alongside an enemy, decimate her crew with discharges of arrows and showers of heavy stones, leaving the way clear for men-at-arms to board, overcome the survivors and take the ship and its crew.

It is not clear how many Castilian caracks were in de le Cerda’s fleet. Probably he had around 30 ships.

King Edward III’s English fleet numbered 50 ships.

Winner of the Battle of Winchelsea: The English fleet defeated the Castilian fleet, destroying or taking many ships.

Account of the Battle of Winchelsea:

On 4th August 1347, the French port town of Calais surrendered to King Edward III after a hard and bitter siege.

In early 1348, following an unsuccessful attempt by the French to recover Calais, King Edward entered into a truce with the French and fighting was largely suspended.

In 1349, Charles de la Cerda with a Castilian fleet intercepted ships of the Gascon wine fleet sailing from Bordeaux to the English south coast, killing the captured ships’ crews by throwing them into the sea.

In December 1349, King Edward and the Black Prince sailed to Calais with a force of troops to forestall an intended attack by Geoffrey de Charni on Calais.

De Charni having been defeated and captured; King Edward returned to England.

In May 1350, the English authorities began preparations to deal with de la Cerda’s fleet which was preying on English shipping, in spite of the truce between England and France.

Ships assembled off the south coast of England: the Thomas, the Edward, the Jonette, the Plenty, the Isabella, the Gabriel, the Michael, the Welfare, the Mariote, the Jerusalem, the Thomas Beauchamp, the Mary, Godibiate, the John, the Edmund, the Falcon, the Buchett and the Lawrence.

King Edward resolved to command the English fleet and two vessels were appointed to serve as the King’s ‘Hall’ and his ‘Wardrobe’, accommodation for the King’s Household and Administration.

On 22nd July 1350, Lord Morley was appointed Admiral of the Northern Fleet, which was contributing several ships to the assembling fleet, although the King was resolved to take overall command.

In mid-August 1350, King Edward addressed the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, informing them of his plans and requesting their prayers.

King Edward then travelled on to Winchelsea, accompanied by the Queen and the Princes.

As the King was taking command, many of England’s leading aristocrats joined the fleet with their retinues, among them the Earls of Lancaster, Derby, Arundel, Hereford, Northampton, Suffolk and Warwick.

They were joined by several prominent peers, Lords Percy, Stafford, Mowbray, Nevill, Clifford, Roos and Greystook and many eminent knights: Sir Reginald de Cobham, Sir Walter Manny, Sir Thomas Holland, Sir Robert de Namur and 400 other knights.

Among the prominent Englishmen who joined the King’s fleet were Richard, Lord Scrope of Bolton, Sir William Scrope, Sir Henry Scrope, Sir John Boyville, Sir Stephen Hales, Sir Robert Conyers and Sir Thomas Banestre.

The King’s young son, John of Gaunt, Earl of Richmond, insisted in joining the fleet, although only 11 years old and too young to wear armour.

Sir Robert de Namur, son of John, Count of Namur, commanded the king’s ‘Hall’, the ship carrying the Royal Household.

King Edward embarked on his favourite ship, the Cog ‘Thomas’.

The English fleet, some 50 vessels, anchored outside Winchelsea to await the arrival of the Castilian fleet.

De la Cerda’s Castilian fleet was in Sluys on the northern coast of Flanders after its exploits capturing English merchantmen in the Channel and North Sea, loading with Flemish goods to take back to Castile.

De la Cerda heard of the English preparations and made his own for the impending battle, equipping his ships with large stones to be hurled down onto the decks of the English ships and hiring troops from the crowds of mercenaries of Flemish and other nationalities that crowded into Sluys.

It is said that, in spite of having fewer ships, the fighting men in the Castilian fleet far outnumbered the fighting men in King Edward’s fleet.

De la Cerda’s ships set sail from Sluys on Sunday, 29th August 1350.

Once the Castilian fleet was in the Channel the wind blew from the north-east taking de la Cerda’s ships on a course along the English coast.

Passing Dungeness, the Castilian ships headed along the coast.

The English fleet, lying off Winchelsea, sighted the Castilian ships in the early evening of Sunday 29th August 1350.

The English ships weighed anchor, trumpets sounded and wine was served to the knights and nobles as they armed for battle.

The two fleets met in a collision.

Edward’s ship, Thomas, struck the leading Castilian vessel, bringing down its mast, but causing the Thomas to spring a serious leak.

The English knights persuaded King Edward to move on and grapple the next Castilian ship.

After a fierce struggle the Castilian ship was taken and its surviving crew thrown into the sea.

The Thomas’s crew transferred to the Castillian ship and the English flagship was left to sink.

The Black Prince’s ship was struck and grappled by a Castilian vessel and was sinking, when the Earl of Lancaster’s crew boarded the Castilian from the far side. The sound of Lancaster’s men’s war cry of St George and Derby’, encouraged the Black Prince’s crew to board from their side.

The Castilian was captured and her crew thrown into the sea; the Black Prince taking over the ship and leaving his own to sink.

The King’s ‘Hall’, commanded by Sir Robert of Namur, found herself in grave danger, grappled by a larger Castilian vessel.

The Castilian set all sail and began to drag the ‘Hall’ out of the battle, where she would be wholly vulnerable to Castilian attack.

The ‘Hall’s crew called for assistance from other English ships but appear not to have been heard.

The situation was saved by Sir Robert’s valet, Hannekin. He leapt, sword in hand, onto the Castilian ship and cut as many of the halliards as he could reach, bringing down the main sail and bringing the ship to a standstill, where it was boarded and taken by the English.

While the greater size of the Castilian ships and their large crews and heavier weaponry enabled de la Corda’s ships to inflict great damage and heavy casualties on the English fleet, the greater number of English ships eventually told against the Castilians and they were heavily defeated.

Casualties in the Battle of Winchelsea:

It seems that the Castilians lost at least half of their ships, most captured by the English with the crews thrown into the sea by the victors.

With their larger numbers of heavy weapons and the advantage of height from their bigger ships, the Castilians managed to inflict heavy casualties on the English crews.

Numbers of casualties among the crews are unclear.

Follow-up:

Following the Battle of Winchelsea the English fleet anchored outside Rye and Winchelsea and King Edward and the Earl of Richmond re-joined the Queen at an abbey some six miles from the shore, where she had been awaiting the outcome of the battle.

The remains of the Castilian fleet returned to Sluys.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Winchelsea:

- The Battle of Winchelsea was also known as the Battle of Lespagnols sur Mer (The Spanish on the Sea).

- The Battle of Winchelsea gained for King Edward III the nicknames of ‘Avenger of the Merchants’ and ‘King of the Sea’.

- It is reported that some cannon were deployed on English ships and that Winchelsea saw the first use by the English of cannon in battle at sea.

- Charles de la Cerda, the Constable of France, was heavily involved in the scheming around the government of France conducted by Charles of Navarre. De la Cerda was murdered by Charles of Navarre in 1354.

- Sir Thomas Banestre was subject to a conviction for murder. The King granted Sir Thomas a pardon for his conduct in the Battle of Winchelsea.

- King Edward III caused a gold coin to be struck to commemorate his victory in the Battle of Winchelsea. The coin shows a single masted ship and the Royal Coat of Arms with the arms of England and France incorporated.

The Royal Navy a History Volume 1 by Laird Clowes

Trial by Fire The Hundred Years War Volume II by Sumption

The Hundred Years War by Robin Neillands.

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of La Roche-Derien

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Mauron