The devastating defeat by the Duke of Bedford’s English army of the French army of the Dauphin and his Scots allies and mercenaries from Lombardy and Castile on 17th August 1424 in the Hundred Years War; a battle described by the French as a ‘Second Agincourt’

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Cravant

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Siege of Orléans

War: Hundred Years War.

Date of the Battle of Verneuil: 17th August 1424

Place of the Battle of Verneuil: at Verneuil 50 miles south of Rouen and 100 miles west of Paris, in France.

Combatants at the Battle of Verneuil: An English army against the Franco-Scottish army of the Dauphin of France with mercenaries from Lombardi and Spain.

Commanders at the Battle of Verneuil: The Duke of Bedford, the deceased King Henry V’s brother and Regent to the young King Richard II, commanded the English army. Vicomte d’Aumale commanded the Franco-Scottish army Vicomte d’Aumale commanded the Franco-Scottish army while Archibald, Fourth Earl of Douglas and Duc de Touraine commanded the Scots contingent..

Size of the armies at the Battle of Verneuil: The English army numbered around 10,000 men. The Franco-Scottish army comprised around 15,000 men.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Verneuil: Knights increasingly wore steel plate armour with visored helmets. Their weapons were lance, shield, sword, various forms of mace or club and dagger. Many carries two-handed swords in battle. Each knight wore his coat of arms on his surcoat and shield.

There were contingents of archers with both the English and Scottish contingents.

The archers carried a powerful bow, capable of many aimed shots a minute.

For hand-to-hand combat archers carried swords, daggers, hatchets and war hammers. They wore jackets and loose hose. Archers’ headgear was a skull cap either of boiled leather or wickerwork ribbed with a steel frame.

The Lombard knights that fought for the French are reported as riding ‘barded’ horses: that is horses in ‘horse armour’: the reason, it is claimed, for their being enabled to overwhelm the archers of the English reserve.

Horses were particularly vulnerable to arrows and, it is said, that the Lombards’ ‘barding’ enabled their horses to survive the English arrow-discharges.

Winner of the Battle of Verneuil: A decisive victory for the English army of the Duke of Bedford.

Events leading to the Battle of Verneuil:

On the death of King Henry V in 1422, his brother the Duke of Bedford, became regent for the minority of Henry’s young son King Richard II.

Bedford also took over Henry’s task in France of enforcing the terms of the Treaty of Troyes, whereby, on the death of the French king Charles VI, the English king, now Richard II, would become King of France, with the Dauphin excluded from the French succession.

For the time being this involved holding Normandy and the north of France while pushing back the areas of the country held by the Dauphin from his base in Bourges.

In 1424, Bedford assembled an English army of around 10,000 men from reinforcements sent from England and from the English garrisons in towns and castles across Northern France, with the intention of advancing into Anjou and Maine in Central France.

Simultaneously, the Dauphinists were resolved to advance north into the territory held by the English and the Burgundian faction, taking such towns and castles as they could.

The Dauphinist army comprised a large French contingent, the Scots army and 2,000 heavily armoured mounted men-at-arms from Lombardi and Castille; 15,000 men in all.

The focal point for the advance of each side was the castle of Ivry, some fifty miles west of Paris, where a Dauphinist garrison under siege by the Earl of Suffolk had undertaken to surrender if not relieved by 14th August 1424.

On 11th August 1424, the Duke of Bedford marched his army from Rouen to Evreux, 20 miles to the north-west of Ivry.

On 13th August 1424, Bedford marched his army to Ivry and joined Suffolk.

Meanwhile the Dauphinist Franco-Scottish army was marching up from Le Mans, arriving at Nonancourt, 20 miles to the south-west of Ivry, intent on relieving the French garrison in Ivry Castle.

Once it was known that Bedford’s English army was at Ivry, the Franco-Scots high command was wracked with dissension.

It was the perceived and accepted knowledge among the senior French commanders that battle with an English army was to be avoided unless the French were in overwhelming strength or there was some other compelling reason.

This was the conclusion drawn from the catastrophic French defeats at Creçy, Poitiers and Agincourt.

The cause of these defeats was correctly seen to be the terrible effectiveness of the English longbows.

The Scottish commanders had not experienced the same level of defeat and, having strong contingents of archers, felt able to give battle to the English, particularly following their success at the Battle of Baugé in 1421.

The French view predominated and the Franco-Scots army marched back to the town of Verneuil which was captured by a trick, a group of Scots soldiers gaining entry to the town by pretending to be English.

When the Dauphinists appeared to withdraw, the Duke of Bedford marched from Ivry to Evreux, leaving the Duke of Suffolk to follow the Franco-Scots army with a small force.

On 15th August, 1424 Suffolk sent word to Bedford that the Dauphinist army was in Verneuil.

Bedford prepared to march south to Verneuil.

Before doing so. Bedford despatched the Burgundian contingent of 3,000 men to Picardy to resume siege operations against Dauphinist towns.

The Battle of Verneuil is not well recorded in contemporary documentation, particularly English and, with no explanation available in the sources, Bedford’s action in dispensing with the Burgundians on the eve of a major battle against a numerically stronger army has been the subject of considerable speculation.

On 16th August 1424, Bedford marched 12 miles south to Damville, a few miles short of Suffolk’s force.

During the day, numbers of Normans deserted from Bedford’s army and returned to Normandy.

In the Dauphinist army, controversy raged whether the advancing English army should be met in the field.

The senior French officers were reluctant, adhering to the direction not to fight the English in open battle.

The Scots were determined to fight Bedford’s army.

One Frenchman commented on the fanatical hatred the Scots showed for the English.

The Scots won the controversy and on 17th August 1424, the Dauphinist army marched out of Verneuil to give battle to the English.

Account of the Battle of Verneuil:

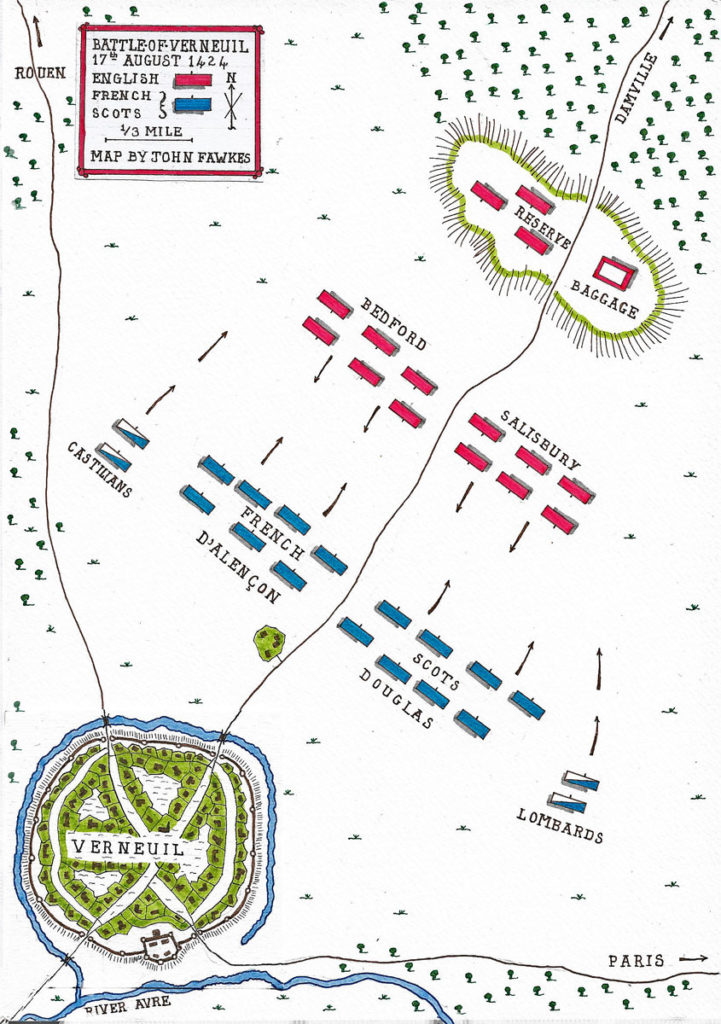

The Dauphinist army took up a position on flat ground a mile out of Verneuil, astride the road leading north-east to Damville.

Douglas’s Scots took position to the right of the road and D’Aumale’s French men-at-arms formed on the left of the road.

Both these substantial contingents dismounted for the battle, in accordance with the practice adopted by both sides as the Hundred Years War progressed, horses being too vulnerable to arrow-fire to be taken into battle.

Knights from states of Europe with no experience of the effect of massed arrow discharges were not prepared to undergo the professional humiliation of fighting on foot. Hence the Lombard and Castilian men-at-arms remained mounted for the battle and were positioned on each flank, the Lombards on the right and the Castilians on the left.

It is stated in various authorities that the Lombards rode ‘barded’ horses; that is horses wearing horse-armour; that being the reason they were so successful against the English archers, being largely impervious to arrow-fire.

The English army emerged from the forest to the north-east of Verneuil, Bedford having joined Suffolk and took up position around 1,000 yards from the Dauphinist line.

The English formed in two divisions, one on each side of the road, the Earl of Salisbury commanding the left and Bedford the right.

Dismounted men-at-arms formed the main body of each division with archers on the flanks.

The baggage was placed in the rear with the waggons formed into a square and the horses tethered inside the square, tied to each other to hinder their removal.

A baggage guard was formed of some 2,000 archers and camp-followers.

The two armies stood facing each other from soon after dawn to late afternoon, each waiting for the other to forego the advantage of the defence and launch an attack.

At around 4pm both sides began to advance.

Within 250 yards of the Dauphinist line, the English archers halted and formed a fence with the sharpened staves they carried.

The French men-at-arms of the Vicomte de Narbonne lunged forward leading the attack by the Dauphinist army.

The English lines greeted the commencement of the battle with a cheer.

The mounted men-at-arms on the flanks of the Dauphinist army put spurs to their horses and charged, but were forced around the English flanks by the barrier of stakes erected by the archers.

The mounted Castilian and Lombard men-at-arms fell on the rear-guard of English archers and dispersed them, before ransacking and looting the English baggage and pursuing the fleeing archers off the field of battle.

In the mean-time the two armies of dismounted men-at-arms joined in combat that was said to have been as fierce as any in the Hundred Years War, the field resounding to the English war-cry of ‘St George Bedford” and the French cry of “St Denis Monjoie”.

The first section of line to give way was the French left wing commanded by the Duc d’Aumale.

The troops of the French left wing fled back towards Verneuil, pursued by Bedford’s division, but, unable to gain access to the town, many fell into the town moat and were drowned.

D’Aumale himself was killed.

The moat brought the pursuing English to a halt and enabled Bedford to rally them and lead them back to the scene of the main battle, where Douglas’s Scots were resolutely fighting with Salisbury’s English division of the left.

The archers of the English reserve reformed after being scattered by the Lombard and Castilian horsemen and joined the assault on the Scots.

Attacked in the front by Salisbury’s men-at-arms, in the left flank by the archers of the English reserve and in the rear by Bedford’s returning division, the Scots were overwhelmed and brought near to annihilation.

Returning from pillaging the English camp and pursuing the fleeing English archers up the Damville road, the Castilian and Lombard horsemen attempted to join the battle but were driven off by the English archers.

Seeing that the battle was lost, they left the field.

Many of the French men-at-arms of the left division managed to escape the battle field.

Casualties at the Battle of Verneuil:

The Duke of Bedford wrote in a letter after the battle that his heralds counted 7,262 Dauphinist dead on the field.

English casualties were reported to have been 2,000 killed, although the Duke of Bedford recorded his losses as two or three men.

The leaders of the Dauphinist army were either killed or captured.

Of the French, the Comte d’Aumale, the Vicomtes de Narbonne, Ventadour and Tonnerre were killed. The Duc d’Alençon and Marechal Lafayette were captured.

Of the Scots, the Earl of Douglas, his son James Stewart and the Earl of Buchan were killed along with Sir Robert Stewart, Sir John Swinton, Sir Alexander Home, Sir Walter Lindsay and many others of rank.

Of the 6,000 men of the Scots army only 40 survived the battle.

For his part in the murder of the Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless, the body of Narbonne was subjected to quartering and his remains hung on a gibbet.

Follow-up to the Battle of Verneuil:

Following the battle, the Duke of Bedford divided his army and advanced into Anjou and Maine, continuing his methodical conquest of Dauphinist territory.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Verneuil:

- On his arrival in France in the spring of 1424 with substantial re-enforcements for the Scots army serving with the French, the Earl of Douglas was made Duke of Touraine and Maréchal of France by the Dauphin. No other foreigner or non-royal Frenchman was appointed a French duke in the 15th Century.

- Some accounts state that the Duke of Bedford sent a letter to the Earl of Douglas on the night before the Battle of Verneuil saying he intended to dine with him. Douglas replied that Bedford was welcome and the table was laid. Bedford’s letter is also said to have offered terms for the Scots in the impending battle. Douglas’s response was that the Scots neither asked for nor offered terms of surrender.

- In the final attack on the Scots, the English troops used the war cry ‘A Clarence’, a reference to the death of the Duke of Clarence at the hands of the Scots in the Battle of Baugé.

- Of the English reserve many fled before the assault by the Lombard and Castilian men-at-arms. One, Captain Young, alleged to have fled with five hundred of his men, was arrested after the battle, hanged drawn and quartered.

- It is said that many French Dauphinists were pleased at the destruction of the Scots army at the Battle of Verneuil, finding their Scots allies insufferably arrogant. This was particularly so in Tours where Archibald Fourth Duke of Douglas had briefly lived as the Duc de Touraine.

- The Dauphin incorporated the Scots men-at-arms who survived the Battle of Verneuil into his new Garde du Corps Écossaise.

- The Duc d’Alençon was ransomed by the Duke of Bedford. The ransom cost the Duc d’Alençon everything he owned. For a time, he was described as the ‘poorest man in France’. He later became a comrade-in-arms to Joan of Arc.

References for the Battle of Verneuil:

The Hundred Years War by Burne

Cursed Kings, Volume IV of the four-volume record of the Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption.

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman.

British Battles by Grant.

The Black Douglases by Michael Brown

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Cravant

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Siege of Orléans