The savage battle on 21st July 1403 that abruptly ended Harry Hotspur’s attempt to wrest the throne of England from King Henry IV

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Homildon Hill

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Siege of Harfleur

War: Hundred Years War.

Date of the Battle of Shrewsbury: 21st July 1403

Place of the Battle of Shrewsbury: at Shrewsbury in the west of England

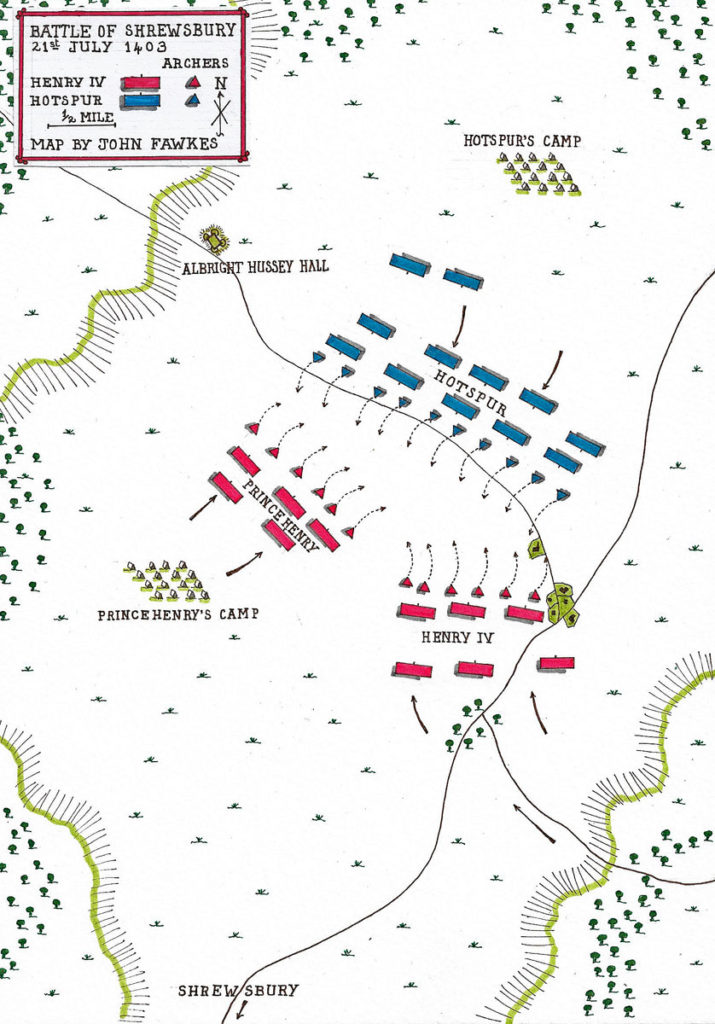

Combatants at the Battle of Shrewsbury: The armies of King Henry IV and Prince Henry of Monmouth, the Price of Wales against the rebel armies of Harry ‘Hotspur’ Percy and his uncle, the Earl of Worcester.

Commanders at the Battle of Shrewsbury: King Henry IV, advised and assisted by the Scots nobleman, George Dunbar, Earl of March, commanded the royal army. Sir Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy, supported by the Scotsman Archibald, Fourth Earl of Douglas commanded the rebel army.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Shrewsbury: There were perhaps 8,000 to 10,000 men on each side with Hotspur’s rebel army being the larger.

A force of Welsh troops was on its way to join Hotspur but failed to arrive in time for the battle.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Shrewsbury: Knights increasingly wore steel plate armour with visored helmets. Their weapons were lance, shield, sword, various forms of mace or club and dagger. Many carried two-handed swords in battle. Each knight wore his coat of arms on his surcoat and shield.

English archers carried a powerful bow.

For hand-to-hand combat archers carried swords, daggers, hatchets and war hammers. They wore jackets and loose hose. Archers’ headgear was a skull cap either of boiled leather or wickerwork ribbed with a steel frame.

Winner of the Battle of Shrewsbury: A decisive victory for King Henry IV, with the death of ‘Hotspur’ Percy and the capture of the Earl of Douglas and the collapse of Hotspur’s rebellion against the King.

Events leading to the Battle of Shrewsbury:

In 1399 Henry Bolingbroke overthrew King Richard II and took the throne of England, becoming King Henry IV.

Richard was imprisoned in Pontefract Castle where he died, probably starved to death on Henry’s orders.

For the rest of his reign Henry IV faced opposition and revolt, with claims being made that Richard II was still alive.

Much of the support for these rebellions came from Cheshire, a county with strong links to King Richard II.

In early 1402 a Scots army, raised and commanded by Archibald, Fourth Earl of Douglas, invaded the north of England, at the instigation of the King of France, who sent a small body of French knights to fight with the Scots.

After ravaging areas of Northumberland, the Scots army was returning to Scotland, when it was intercepted by an English army led by the Earl of Northumberland and his son Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy.

The English army was accompanied by the Scots nobleman George Dunbar, Earl of March.

The battle between the Scots and English armies took place at Homildon Hill near the Northumberland town of Wooler on 7th May 1402.

The Scots were heavily defeated, decimated by the arrow discharges of the English archers.

Some eighty Scottish nobles and knights were taken prisoner together with two French knights.

It was the convention of the time that prisoners taken in battle became the property of the captor who was entitled to ransom the prisoner and retain whatever sum was raised by the ransom.

The Earl of Douglas, recovering from the wound he received in the battle, was the prisoner of Hotspur who expected to receive a substantial amount from the ransom of Douglas and his other prisoners.

It was apparent to King Henry IV that the ability of Scotland to wage war against England would be severely hampered if these senior and experienced soldiers remained prisoners of the English.

The King directed that the Scots prisoners were not to be ransomed and that Douglas was to be delivered into royal custody.

Hotspur refused to hand over Douglas.

Resentment at the attempt to deprive them of their legitimate spoils of war appears to have been the trigger for Hotspur and his father the Earl of Northumberland to revolt against King Henry IV.

An additional source of grievance for the Percies was the King’s promotion of the interests of his brother-in-law, Ralph Neville, Early of Westmorland, the Percies’ rival in the Border Region. Neville’s main area of influence was on the Western Border with Scotland, while the Percies’ was in Northumberland on the Eastern Border.

It was a grave error on the part of King Henry IV to alienate the Percies, with their wide influence in the North of England, Yorkshire and the western Midlands and Welsh Borders and their intensely loyal following among the tenants of their extensive estates in these areas.

It seems likely that Hotspur made an agreement with the Earl of Douglas to release him without ransom if Douglas would join the Percy revolt against King Henry IV.

In April 1403, Hotspur invaded the Douglas estates in Teviotdale and besieged a minor castle called Cocklaws.

Douglas accompanied Hotspur and seems to have used the invasion as the opportunity to raise troops among his tenants to serve in Hotspur’s rebel army.

The Percies also corresponded with the Welsh leader Owen Glendower and an agreement was reached to act in concert against the King.

Glendower raised an army in Carmarthenshire and captured Carmarthen Castle, causing the Welsh to rise in rebellion along the border.

King Henry IV was marching north, intending to join the Percies invasion of Scotland, when he learned at Nottingham that the Percies were in rebellion against him.

Hotspur had left the Cocklaws army and marched south with the Earl of Douglas and a small band of men-at-arms. Hotspur reached Cheshire on his way to the Welsh Borders and raised a new army from his family’s supporters in the county, also sending messages to potential supporters across England.

Hotspur claimed that King Richard II was still alive and was with his father, the Earl of Northumberland, in the North of England. This was untrue, as Hotspur knew.

In the meantime, the Earl of Northumberland brought his army back to England from Scotland and remained to recruit troops from Northumberland and the north of Yorkshire, with the intention of following his son to the Welsh Borders.

Hotspur decided to lead his army to Shrewsbury and attack the Prince of Wales’s army there, without waiting for his father, now delayed in raising his army in the North.

A Welsh army moved towards Lichfield to intercept the King’s army.

The King was advised by Henry Dunbar, Earl of March, who was marching with him, to advance as quickly as possible to Shrewsbury, combine with the Prince’s army and give battle to Hotspur before the Earl of Northumberland could reinforce him with his northern army.

Dunbar urged the King not to await the arrival of the troops he had summoned from across England but to attack Hotspur without delay.

Account of the Battle of Shrewsbury:

King Henry IV’s army reached Shrewsbury on 20th July 1403 and joined the Prince of Wales’s army.

Hotspur’s army reached Shrewsbury later the same day.

The King’s and Prince’s armies were drawn up in battle array and advanced on Hotspur’s camp, taking him by surprise.

There were some desultory and inconclusive negotiations, but Dunbar urged the King to launch an immediate attack, advice that he adopted.

Both sides suffered heavily from the opening volleys of arrows before the men at arms engaged, leading to a savage fight between the two armies.

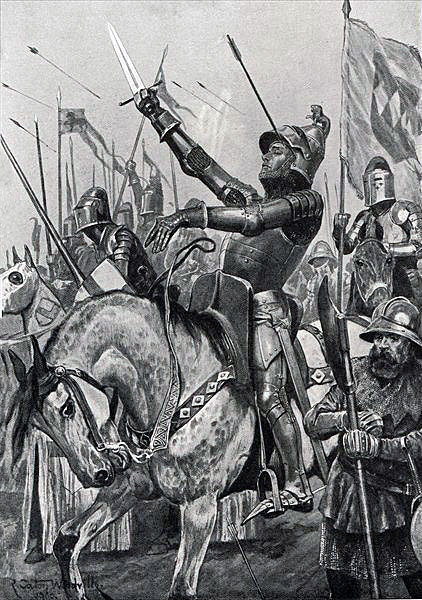

Hotspur and Douglas charged towards the man they thought to be King Henry IV, but there were a number of men acting as the King’s double, dressed in the King’s livery and accompanied by a royal standard and distributed throughout the Royal Army, a ploy that seems to have been arranged by Dunbar.

Accompanied only by their immediate retainers, Hotspur and Douglas found themselves cut off in the midst of the Royal army, where Hotspur was killed and Douglas wounded and captured.

The cry that Hotspur was dead went up across the battlefield and the rebel army began to melt away, leaving its leaders to be taken prisoner.

Casualties at the Battle of Shrewsbury:

The corpses on the battlefield were counted and found to number 1,847, mostly rebels.

An additional 3,000 corpses were found over the route of the three-mile flight of the rebels from the field.

All the surviving rebel leaders were captured, Douglas becoming an English prisoner for the second time within the year.

Follow-up to the Battle of Shrewsbury:

The Earl of Northumberland had been long delayed in raising his army in Yorkshire.

Marching south to join his son, Hotspur, Northumberland was confronted by an army led by the Earl of Westmorland.

Northumberland retreated north before appearing before King Henry and submitting to him.

While initially stripped of his offices and domains, Northumberland was reinstated and his lands returned to him. The Percies were too important for the defence of the North of England against Scottish aggression to be dispensed with.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Shrewsbury:

- Hotspur was struck and killed by an arrow in the face when he opened his visor during the battle. He was buried near the battlefield. Hotspur’s body was later disinterred and his head exhibited on one of the gates of York. Hotspur’s uncle, the Earl of Worcester, was executed for treason the day after the battle, as were all the captured rebel leaders.

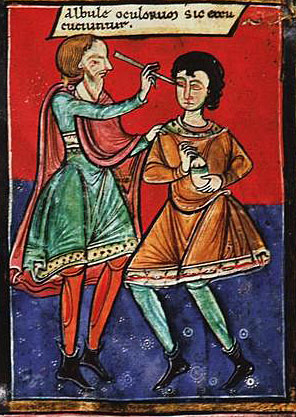

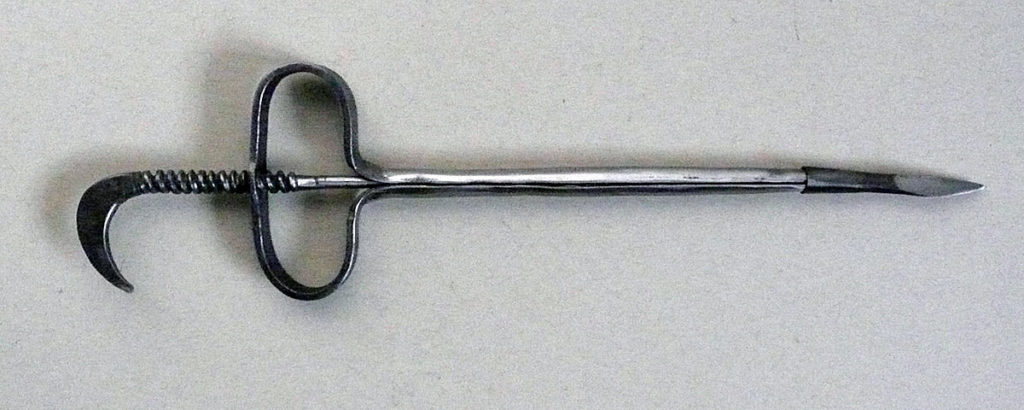

- King Henry IV’s son, the 16-year-old Henry of Monmouth, Prince of Wales, later King Henry V, was struck in the face by an arrow during the Battle of Shrewsbury. The arrow penetrated deep into his cheek by the nose. The prince refused to leave the battlefield to seek treatment until the battle was won, in case his premature departure discouraged his men. After the battle, Prince Henry was treated by the eminent London surgeon John Bradmore. The arrow shaft was removed leaving the arrowhead deeply embedded in the Prince’s face. Bradmore worked an especially constructed tool into the Prince’s cheek with which he extracted the arrowhead. He then treated the wound with a mixture of flour, barley, honey and flax until the Prince recovered. Bradmore’s achievement brought him considerable acclaim and reward. It is reported that Bradmore was brought from prison where he was serving a sentence for forging currency to treat the Prince.

References for the Battle of Shrewsbury:

Cursed Kings, Volume IV of the four-volume record of the Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption.

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman.

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Homildon Hill

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Siege of Harfleur