The French victory over the English on 18th June 1429 in the Hundred Years War inspired by Joan of Arc

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of the Herrings

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Formigny

War: Hundred Years War.

Date of the Battle of Patay: 18th June 1429

Place of the Battle of Patay: In France, near the town of Patay to the north of Orléans

Combatants at the Battle of Patay: A French against an English army.

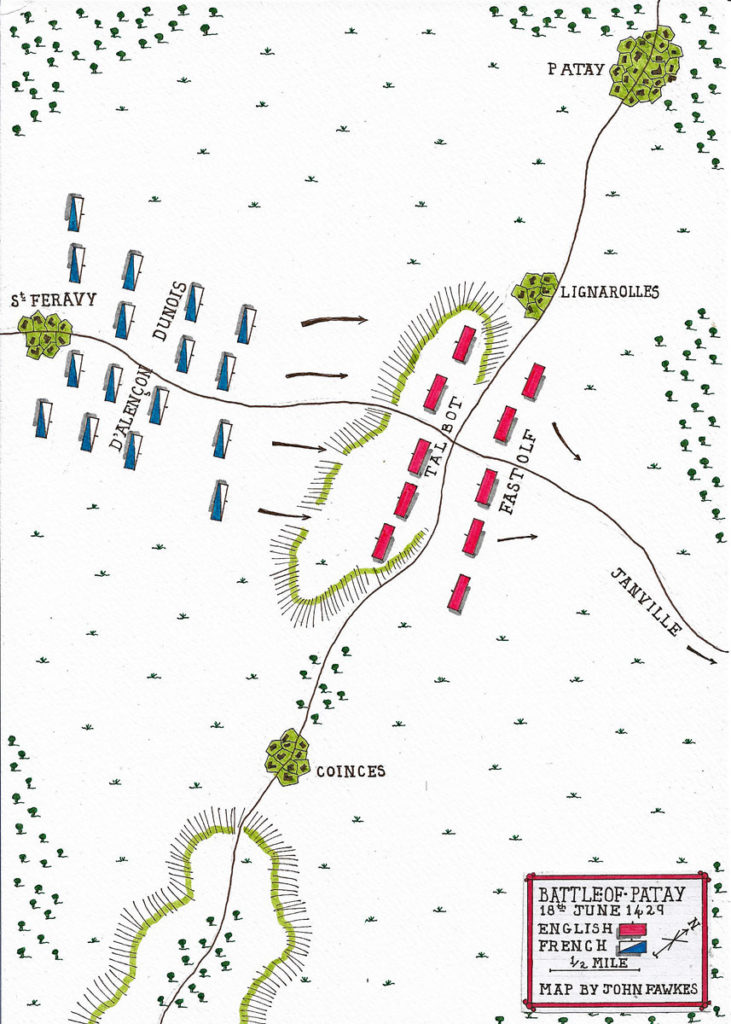

Commanders at the Battle of Patay: The Comte d’Alençon and Dunois, half-brother of the Duke of Orléans, known as ‘the Bastard of Orléans’ led the French army.

Joan of Arc was forced to remain in the rear with the Constable of France, Comte Arthur de Richemont.

Lord John Talbot commanded the advanced body of the English force while Sir John Fastolf’s men remained in the rear.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Patay: The French army numbered around 5,000 men. The English army numbered around 1,000 men.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Patay: Knights increasingly wore steel plate armour with visored helmets. Their weapons were lance, shield, sword, various forms of mace or club and dagger. Many carried two-handed swords in battle. Each knight wore his coat of arms on his surcoat and shield.

The English archers carried a powerful bow, capable of many aimed shots a minute.

For hand-to-hand combat archers carried swords, daggers, hatchets and war hammers. They wore jackets and loose hose. Archers’ headgear was a skull cap either of boiled leather or wickerwork ribbed with a steel frame.

By the time of the Battle of Patay, artillery was a well-established weapon of war although there is no indication that artillery was used in the battle.

Winner of the Battle of Patay: The French decisively defeated the English, capturing Lord Talbot and several other senior English commanders and causing the main body of the English army under Sir John Fastolf to flee the field.

Events leading to the Battle of Patay:

In 1428, the English with their Burgundian allies-controlled Paris and much of Northern France.

The Dauphin, the mainspring of French resistance to the invading English, controlled France south of the River Loire from his de facto capital, the city of Bourges.

In mid-1428, the English regent and military commander, the Duke of Bedford, resolved to capture the City of Orléans.

Orléans lies mid-way between Paris and Bourges and is an important crossing point over the River Loire, the northern boundary of the Dauphin’s territory.

In October 1428 the English army, commanded until his death in November 1428 by the Earl of Salisbury and thereafter by the Earl of Suffolk, began the siege of Orléans.

Battle of Patay:

Following the collapse of the English siege of Orléans in May 1429, substantially due to the inspirational intervention of Joan of Arc, giving rise to her sobriquet of the ‘Maid of Orléans’, the English army dispersed to the towns of Jargeau, Meung and Beaugency along the River Loire.

On 12th June 1429, the French army commanded by d’Alençon and Dunois, but accompanied and inspired by Joan of Arc, stormed Jargeau, putting the English garrison to the sword, other than the Earl of Suffolk and other senior English commanders who were captured and held for ransom.

On 18th June 1429, the English garrison in Beaugency handed the town to the French and marched away under terms of surrender.

The garrison was unaware that Sir John Fastolf was within a few miles of the town, preparing to affect its relief.

Fastolf had marched from Paris at the beginning of June 1429 with an army to relieve the Loire garrisons.

The size of his army is unclear but was probably around 3,000 men, made up of men taken from the depleted Normandy garrisons and French Burgundians.

Fastolf was joined at Janville by Lord John Talbot who had come north from Beaugency to organise the relief of the town.

Fastolf and Talbot marched to Beaugency but were too late to relieve the English garrison.

With the failure to relieve Beaugency and faced by the French armies that had been attacking Beaugency and Meung, Fastolf and Talbot fell back towards Janville.

Urged on by Joan of Arc the French army marched in pursuit of the English, further reinforced by the arrival of Arthur de Richemont, the Constable of France, with a force of 1,000 Bretons.

The French outmarched the retreating English army, hampered by the slow movement of its baggage, coming up with the English near the small town of Patay.

Aware that the French were approaching, Sir John Fastolf deployed his army along the high ground to the south of Patay, while Sir John Talbot took his small force, reinforced with archers from the main army, onto the plateau between Fastolf’s men and the advancing French.

The French advanced guard comprised a well-mounted force of men-at-arms, commanded by La Hire and Poton de Xantrailles, followed by the main body under d’Alençon and Dunois.

The rear-guard was led by de Richemont, the Constable, and was accompanied by Joan of Arc.

It is said that the English archers gave away their positions by ‘halloa-ing’ a stag that broke cover in front of them.

The French advanced guard charged home on the English archers, who are said to have been taken by surprise, overwhelming them and putting the survivors to flight.

Sir John Talbot was captured mounting a horse, but without spurs, indicating that he was unprepared for the French attack.

Fastolf managed to disengage from the battle and withdrew with a sizeable English force towards Janville, where the gates were shut against him, forcing him to continue his retreat towards Paris.

The French were left holding the field of battle with substantial numbers of prisoners and many English casualties.

Casualties at the Battle of Patay: French casualties in the battle were slight. English casualties are not reliably reported but were probably several hundred.

Follow-up to the Battle of Patay:

The Dauphin’s army might well have exploited its successes in relieving Orléans and defeating the English at Patay by advancing on Paris. Instead, at the urging of Joan of Arc, the Dauphin concentrated on reaching Rheims, there to be crowned King of France.

Anecdotes and Traditions from the Battle of Patay:

- Talbot blamed the English defeat on Fastolf for escaping from the battle with his men, leaving Talbot unsupported. It may be that Fastolf was simply accepting that defeat was a ‘fait accompli’ and was attempting to save the remnants of the English army before they were overwhelmed, it is clear that Talbot’s criticism did Fastolf considerable harm. After a cursory investigation instigated by the Duke of Bedford, the English Regent of France, Fastolf was suspended from his membership of the Order of the Garter, although his membership was returned after a more thorough consideration of the allegations against him.

- After the battle Talbot was held by both sides to be a hero. A street in the town of Patay was named ‘Talbot’ and in London a fund was established to assist Talbot pay for his ransom.

References for the Battle of Patay:

Volume V of the four-volume record of the Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption.

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman.

The Hundred Years War by Burne

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of the Herrings

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Formigny