The Scots Earl of Douglas’s defeat of his long standing English rival, Sir Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy, Earl of Northumberland, on the England/Scotland Border on 5th August 1388

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of La Rochelle

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is Battle of Homildon Hill

War: Hundred Years War.

Date of the Battle of Otterburn: 5th August 1388.

Place of the Battle of Otterburn: In Northumberland near the Scottish border.

Combatants at the Battle of Otterburn: An English army against a Scots army.

Commanders at the Battle of Otterburn: Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland led the English army. James, Second Earl of Douglas led the Scots army.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Otterburn: It is difficult to establish the sizes of the two armies. Grant gives the size of the Scots army led by Douglas as 300 men-at-arms and 2,000 infantry. The English army led by Percy comprised the garrison of Newcastle. Grant states that the garrison was ‘too slender to attack Douglas in the field.’

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Otterburn: Knights increasingly wore steel plate armour with visored helmets. Their weapons were lance, shield, sword, various forms of mace or club and dagger. Many carries two-handed swords in battle. Each knight wore his coat of arms on his surcoat and shield.

English archers carried a powerful bow.

For hand-to-hand combat archers carried swords, daggers, hatchets and war hammers. They wore jackets and loose hose. Archers’ headgear was a skull cap either of boiled leather or wickerwork ribbed with a steel frame.

The Scottish infantry were largely peasants armed with spears and whatever cutting or striking implements were available to them.

Winner of the Battle of Otterburn: A decisive victory for the Scots.

Account of the Battle of Otterburn: Throughout the Hundred Years War Scotland fought England in alliance with France, the ‘Auld Alliance’. In the 1380s, Scotland with French assistance sought to take advantage of the divisions in England between King Richard II and his barons.

In 1388 senior Scottish nobles conferred at Jedburgh, without the knowledge of King David II, to decide on a strategy to exploit the current English weakness. They decided to launch an attack across the border.

In August 1388 these Scottish nobles gathered an army at Yetholm in the Cheviot Hills; the Earl of Douglas, Earl of Moray, Earl of Fife, Sir James Lindsay and others bringing 1,200 men-at-arms and a mass of common soldiers.

While at Yetholm, the Scots captured an English spy, who, under interrogation, revealed that an English army was assembling south of the border, but was waiting to see whether the Scots invasion was to be by the western or eastern route. Whichever it was the English army would mount a counter-invasion by the other route.

In the light of this information the Scots resolved to attack England by both routes: the Earl of Lindsay invading with a larger army via Lidderdale and Carlisle and the Earl of Douglas marching with a smaller force by the eastern route to Durham.

Douglas marched to Durham, without pausing to ravage the countryside which was the usual practice in border warfare and turned north to head for the border.

Douglas’s army passed Newcastle where the English garrison was commanded by Sir Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, nicknamed ‘Hotspur’.

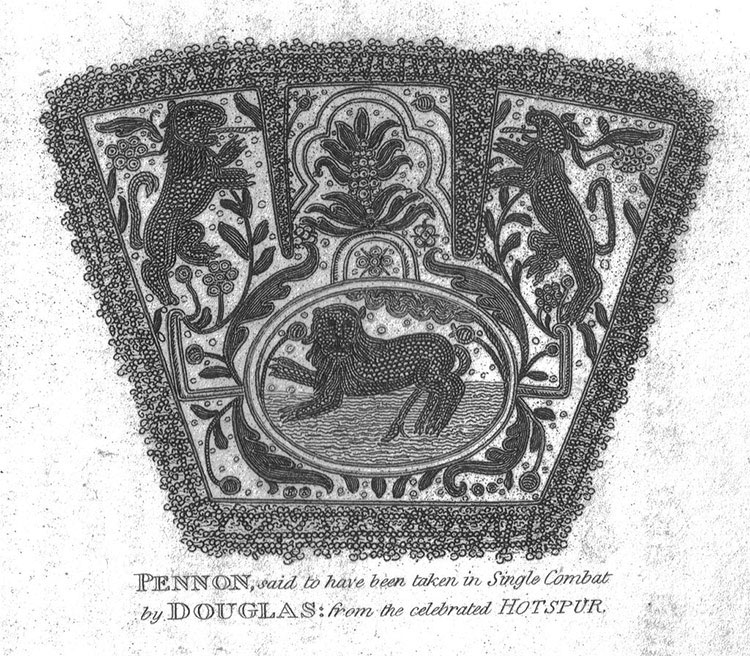

Douglas and Hotspur met in single combat. Douglas overcame Hotspur and took his lance and pennon.

Before he rode off, Douglas challenged Hotspur to recover his lance from outside Douglas’s tent in the Scots encampment.

The Scots army continued its march to the border and encamped, expecting the English to attack and Hotspur to attempt to recover his lance.

However, the directions of the senior English commanders were that Hotspur should not attack as they believed the whole Scots army was present, considerably outnumbering Hotspur’s force.

After waiting for Hotspur to make his attack, Douglas continued his march to the Scots border.

Douglas stormed and destroyed the castle of Ponteland, before marching on to Otterburn in Redesdale, where he intended to attack the castle.

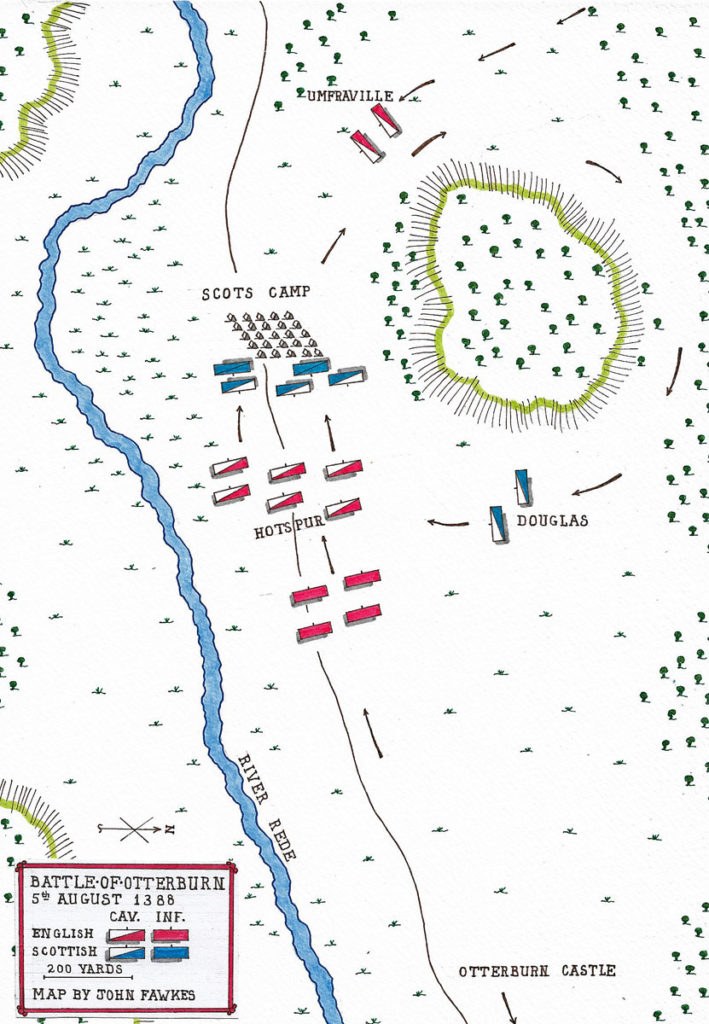

The Scots camped near to the River Rede, with a marsh on one side and a forested hill on the other.

The Scots began their attack on Otterburn Castle before retiring to their camp for the night.

Hotspur, now with the knowledge that Douglas’s force was a small detachment from the main Scots army, hurried to overtake Douglas with his force of men-at-arms and foot soldiers.

Accounts in contemporary records give Hotspur a force of 6,000 men-at-arms and 8,000 infantry. It would seem most unlikely that his army was that large.

Hotspur’s army arrived at the Scottish camp at sunset on the day that is given by some authorities as 5th August 1388.

As the main English army approached the Scottish camp, Sir Robert de Umfraville, Lord of Redesdale, used his local knowledge to lead a party by a circuitous route through the woods to the north to approach the Scottish camp from the rear.

After a strenuous day assaulting the castle, the Scots were eating their evening meal and retiring for the night.

Hotspur’s men immediately launched an attack.

The Scots army’s waggons appear to have been formed into a laager around the camp.

Defended by the camp followers these waggons delayed the English attack sufficiently for the Scots knights and men-at-arms to re-arm, at least partially, before entering the battle.

Douglas and Moray are said to have fought through the battle without helmets.

The English attempted to penetrate between the camp and the River Rede and became bogged down in the marshy area.

Douglas assembled such mounted men as were ready and led them around the hill and into an attack on Hotspur’s flank.

The fighting between English and Scots went on through the night.

The greater English numbers told and slowly the Scots were driven back.

Douglas, wielding a battle axe and accompanied by his closest companions, hacked his way into the English ranks, where he fell mortally wounded.

Douglas’s initiative was pressed by Sir John Swinton, another Scots Border stalwart, shouting with his companions the war cry of ‘a Douglas’ and the English began to give way.

Hotspur was wounded and captured by the Earl of Moray and the English army fled.

While the main battle was taking place to the east of the Scottish camp, de Umfraville’s party is believed to have ransacked the camp and then retired by the route they had come, taking no part in the battle.

Casualties at the Battle of Otterburn: It is believed that the only Scots of ‘quality’ to have fallen in the battle, in addition to the Earl of Douglas, were Sir Robert Heriot, Sir John Touris of Inverleith and Sir William Lundin.

From the English army, Hotspur’s brother Sir Ralph Percy, Sir Ralph Langley the Seneschal of York, Sir Robert Langley, Sir Robert Ogle, sir John Lilburn, Sir John Copeland, Sir Thomas Walsingham, Sir John Felton, Sir Thomas Abingdon and ‘half the chivalry of the Northern Shires’ were captured.

It is said that 1,800 English men-at-arms were killed in the battle and 1,000 captured.

Follow-up to the Battle of Otterburn:

The Bishop of Durham arrived in the area with an army soon after the battle, but refrained from attacking the Scots army, which withdrew into Scotland unmolested.

The body of Douglas was taken to Melrose Abbey Church and buried in his ancestral tomb.

While the smaller Scots army was conducting this successful campaign in the eastern counties of Northern England, the main Scots army ravaged the English countryside in the west.

It was reported that the chivalry of the western army was deeply jealous of the sums received for the ransom of the English prisoners taken at Otterburn.

Froissart puts the sum for these ransoms at 200,000 francs.

For his ransom, Hotspur built the castle of Penrose in Ayrshire for Lord Montgomerie.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Otterburn:

- Hotspur launched the English attack as night was falling, giving no opportunity to use the English archers in the battle, undoubtedly a factor leading to Hotspur’s defeat.

- Froissart in his account of the Battle of Otterburn states ‘Of all the battles that have been described in this history, great and small, this was the best fought and the most severe; for there was not a man, knight or squire, who did not acquit himself gallantly hand in hand with his enemy, without stay or faint-heartedness.’

- A ballad came into existence in the 15th Century recording the Battle of Otterburn. This in turn gave rise to the ‘Ballad of Chevy Chase’. The ‘Ballad of the Battle of Otterburn’ is set out below.

References for the Battle of Otterburn:

The Hundred Years War by Alfred H. Burne

Divided Houses, Volume lII of the four-volume record of the Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption.

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman.

The Hundred Years War by Robin Neillands.

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of La Rochelle

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is Battle of Homildon Hill

The Ballad of the Battle of Otterburn

| It fell about the Lammas tide, When the muir-men win their hay, The doughty Douglas bound him to ride Into England, to drive a prey. He chose the Gordons and the Graemes, With them the Lindesays, light and gay; But the Jardines wald nor with him ride, And they rue it to this day. And he has burn’d the dales of Tyne, And part of Bambrough shire: And three good towers on Reidswire fells, He left them all on fire. And he march’d up to Newcastle, And rode it round about: “O wha’s the lord of this castle? Or wha’s the lady o’t ?” But up spake proud Lord Percy then, And O but he spake hie! “I am the lord of this castle, My wife’s the lady gaye.” “If thou’rt the lord of this castle, Sae weel it pleases me! For, ere I cross the Border fells, The tane of us sall die.” He took a lang spear in his hand, Shod with the metal free, And for to meet the Douglas there, He rode right furiouslie. But O how pale his lady look’d, Frae aff the castle wa’, When down, before the Scottish spear, She saw proud Percy fa’. “Had we twa been upon the green, And never an eye to see, I wad hae had you, flesh and fell; But your sword sall gae wi’ mee.” “But gae ye up to Otterbourne, And wait there dayis three; And, if I come not ere three day is end, A fause knight ca’ ye me.” “The Otterbourne’s a bonnie burn; ‘Tis pleasant there to be; But there is nought at Otterbourne, To feed my men and me. “The deer rins wild on hill and dale, The birds fly wild from tree to tree; But there is neither bread nor kale, To feed my men and me. “Yet I will stay it Otterbourne, Where you shall welcome be; And, if ye come not at three day is end, A fause lord I’ll ca’ thee.” “Thither will I come,” proud Percy said, “By the might of Our Ladye!” – “There will I bide thee,” said the Douglas, “My troth I plight to thee.” They lighted high on Otterbourne, Upon the bent sae brown; They lighted high on Otterbourne, And threw their pallions down. And he that had a bonnie boy, Sent out his horse to grass, And he that had not a bonnie boy, His ain servant he was. But up then spake a little page, Before the peep of dawn: “O waken ye, waken ye, my good lord, For Percy’s hard at hand.” “Ye lie, ye lie, ye liar loud! Sae loud I hear ye lie; For Percy had not men yestreen, To fight my men and me. “But I have dream’d a dreary dream, Beyond the Isle of Skye; I saw a dead man win a fight, And I think that man was I.” He belted on his guid braid sword, And to the field he ran; But he forgot the helmet good, That should have kept his brain. . When Percy wi the Douglas met, I wat he was fu fain! They swakked their swords, till sair they swat, And the blood ran down like rain. But Percy with his good broad sword, That could so sharply wound, Has wounded Douglas on the brow, Till he fell to the ground. . Then he calld on his little foot-page, And said – “Run speedilie, And fetch my ain dear sister’s son, Sir Hugh Montgomery. “My nephew good,” the Douglas said, “What recks the death of ane! Last night I dreamd a dreary dream, And I ken the day’s thy ain. “My wound is deep; I fain would sleep; Take thou the vanguard of the three, And hide me by the braken bush, That grows on yonder lilye lee. “O bury me by the braken-bush, Beneath the blooming brier; Let never living mortal ken That ere a kindly Scot lies here.” He lifted up that noble lord, Wi the saut tear in his e’e; He hid him in the braken bush, That his merrie men might not see. The moon was clear, the day drew near, The spears in flinders flew, But mony a gallant Englishman Ere day the Scotsmen slew. The Gordons good, in English blood, They steepd their hose and shoon; The Lindesays flew like fire about, Till all the fray was done. The Percy and Montgomery met, That either of other were fain; They swapped swords, and they twa swat, And aye the blood ran down between. “Yield thee, now yield thee, Percy,” he said, “Or else I vow I’ll lay thee low!” “To whom must I yield,” quoth Earl Percy, “Now that I see it must be so ?” “Thou shalt not yield to lord nor loun, Nor yet shalt thou yield to me; But yield thee to the braken-bush, That grows upon yon lilye lee!” “I will not yield to a braken-bush, Nor yet will I yield to a brier; But I would yield to Earl Douglas, Or Sir Hugh the Montgomery, if he were here.” As soon as he knew it was Montgomery, He stuck his sword’s point in the gronde; The Montgomery was a courteous knight, And quickly took him by the honde. This deed was done at Otterbourne, About the breaking of the day; Earl Douglas was buried at the braken bush, And the Percy led captive away. |