The first land battle between the English and the French of the Hundred Years War fought in Brittany on 30th September 1342

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Sluys

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Auberoche

Date of the Battle of Morlaix: 30th September 1342

Place of the Battle of Morlaix: in the North-West of Brittany in France.

Combatants at the Battle of Morlaix: An English army against a Breton/French army.

Commanders at the Battle of Morlaix: The Earl of Northampton commanded the English army. Charles of Blois, the claimant Duke of Brittany, commanded the Breton/French army.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Morlaix: The English army comprised around 3,000 men. The army of Charles of Blois is said to have been several times larger than the English.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Morlaix: The English army comprised a core of knights and men-at-arms with a strong force of archers.

Increasingly during the 14th Century soldiers in an English army in France were all mounted to enable the army to move at speed.

The Battles of Bannockburn in 1314 and Halidon Hill in 1333, both fought against the Scots, moulded English tactics, causing them to abandon the headlong mounted charge and form their armies with knights and men-at-arms as a dismounted central core with the archers pushed forward on the flanks,

The French continued to believe that battles would be won by a massed mounted charge of nobles, knights and men-at-arms delivered against the opposition’s line.

The English had learnt to their considerable cost at Bannockburn the dangers of a mounted attack against a dismounted line armed with spears.

At the battles of Dupplin Moor in 1332 and Halidon Hill in 1333 the English used their archers to strike down the Scots attacks, the stratagem they then pursued so successfully against the French throughout the Hundred Years War.

The weapon of the English archer was a six-foot yew bow discharging a feathered arrow a cloth metre in length. Arrows were fired with a high trajectory, descending on the approaching foe at an angle. The rate of fire was up to one arrow every 5 seconds. For close quarter fighting the archers used hammers or daggers to batter at an adversary’s armour or penetrate between the plates.

the particular strength of the English army lay in its archers with their life-time of training in the use of the longbow, enabling them to deliver a storm of arrows at a high rate of fire.

Winner of the Battle of Morlaix: The English army repelled at least two French attacks. After the battle both sides initially remained on the battlefield before retreating, the French having suffered significantly more casualties than the English.

Background to the Battle of Morlaix:

The 100 Years War between England and France began in 1337. There were a number of issues between the Kings of the two countries. Among them were the security of Gascony for the English King, the encouragement the French Kings gave the Scots to attack England, the English encouragement of rebellion against the French King in the regions of north-eastern France and above all the English Kings’ claim to the throne of France.

During the course of this long war there were periods of French civil war, particularly over the accession to some of the great estates, which the English King exploited by allying himself to one of the sides.

The first of these disputed accessions was over the Dukedom of Brittany.

In April 1341 Duke John of Brittany died leaving no direct heir with his succession in doubt.

The two claimants to the dukedom were Charles, Count of Blois, married to the deceased duke’s niece, Joan of Ponthièvre and John de Montfort, the deceased duke’s step-brother by his father’s second wife, the widow of King Alexander II of Scotland.

Charles of Blois was the nephew of King Philip VI of France, who strongly supported his claim to the Duchy of Brittany.

The claim of John de Montfort was consequently supported by King Edward III of England.

The two parties began a war to take Brittany.

In November 1341, Charles of Blois with a strong Breton/French army captured the city of Nantes and with it John de Montfort, who was imprisoned in Paris.

The resistance on behalf of John de Montfort was continued by his wife, the redoubtable Joan of Flanders.

After some successes, Joan of Flanders was besieged by Charles of Blois in the estuary town of Hennebont in the south-west of Brittainy.

Joan of Flanders appealed to King Edward III of England for help and a force was dispatched from England under Sir Walter Manny, finally arriving in May 1342 and relieving the now hard-pressed Hennebont garrison, before beginning a campaign against the supporters of Charles of Blois.

On 14th August 1342 another English army landed at Brest on Cape Finisterre, the north-west point of Brittany, comprising 3,000 men commanded by the Earl of Northampton.

Charles of Blois was besieging Brest and was forced by the arrival of Northampton’s army to raise the siege and withdraw to Guingamp, 40 miles to the east.

Northampton advanced to Morlaix and made an unsuccessful attempt to storm the town, before beginning a regular siege.

Battle of Morlaix:

Charles of Blois, invoking his support among the French speaking nobles of northern Brittany, assembled a powerful army, before advancing on 29th September 1342 to relieve Morlaix and give battle to Northampton’s English army.

On hearing of the approach of the French army, the Earl of Northampton left his siege lines outside Morlaix and advanced to meet him.

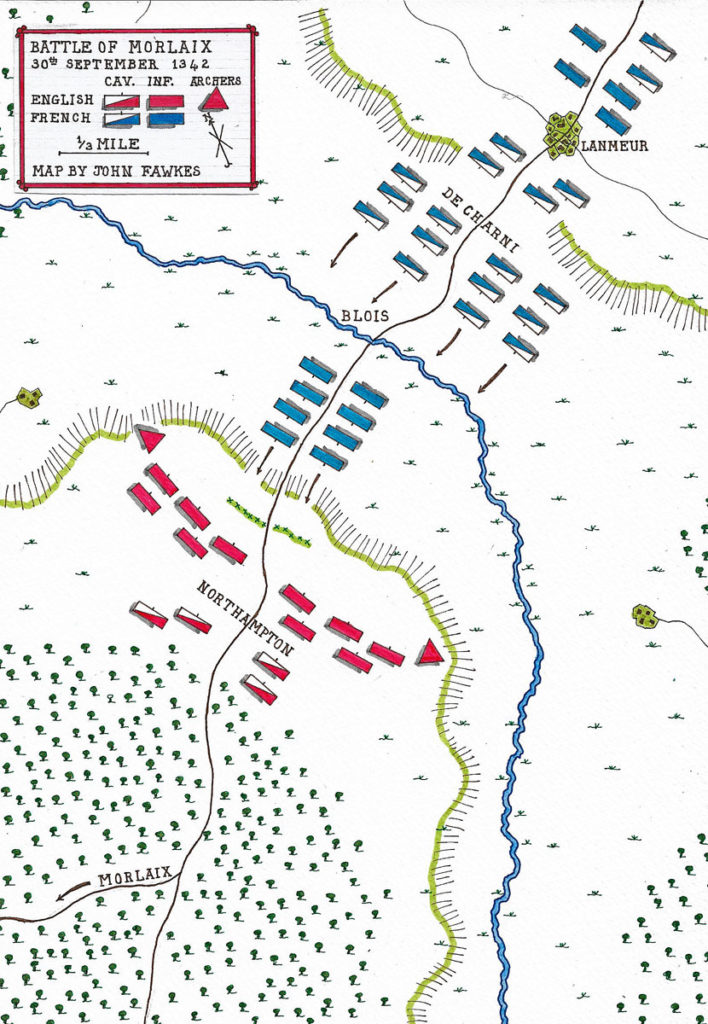

Northampton’s army took up a position on the road from Morlaix in front of a wood through which the road passed.

The road inclined away from the English position to the east, before rising to the village of Lanmeur, some 2 miles from the wood.

The English army formed a line across the road, its knights and men-at-arms dismounted in the centre with the archers on each flank.

The English dug a trench in front of their line as a trap for the French.

Burne states that the English will particularly have had in mind the effectiveness of the pits dug by the Scots at Bannockburn in 1314.

The trench is said to have been concealed with branches and grass.

As the English can only have been in position a matter of hours before the French attack it must be questioned whether there was time to dig much of a trench.

The French army marched through the village of Lanmeur and began its attack on the English positions at around 3pm.

Charles of Blois’ army was formed in three large bodies of troops, in all several times the size of the English force facing it.

The first body leading the advance west along the Morlaix road was formed of dismounted Breton peasants armed with whatever weapons were available to them.

This body, in reality little more than an armed mob, advanced on the English position.

A single discharge of arrows was sufficient to put the peasant body in swift retreat before it reached the concealed trench.

There was a confused pause, while Charles of Blois contemplated the summary repelling of his first attack, before the second was launched.

The second French attack was made by the knights and mounted men-at-arms, who charged the English line.

This charge was brought up short by the concealed trench, into which the leading ranks fell, under further discharges of English longbow arrows.

A small party of some 200 French horsemen continued the charge beyond the trench but were overcome by the dismounted English men-at-arms, their leader Geoffrey de Charni being taken prisoner.

After a further pause, the third French body of mounted knights and men-at-arms began to advance, spreading out to outflank the now revealed and largely blocked trench and the English line.

His archers short of arrows, Northampton’s army fell back to positions along the edge of the wood. Skirmishing took place, with the French troops spilling around the English flanks.

But the attack on the English positions was not pressed.

Much of the French army had by now left the field, including its Genoese crossbowmen.

As night fell Charles of Blois’ army fell back to Lanmeur, the plan to relieve Morlaix abandoned.

Casualties at the Battle of Morlaix: French casualties were heavy. 50 knights were killed in the mounted attack on the English line, with 150 taken prisoner, including the commander of the attack, Geoffrey de Charni.

Accounts of casualties differ widely, some placing French losses in the tens of thousands. There was no frenzied pursuit so it seems unlikely the French casualties were more than the high hundreds or low thousands, with English casualties perhaps as low as less than a hundred.

Almost certainly the ‘armed peasant’ section of Charles of Blois’ army dispersed to their homes after the battle, making it difficult to assess French losses from the battle as opposed to by desertion.

Follow-up to the Battle of Morlaix: Charles of Blois was enabled to continue his campaign to take Brittany after a short period of recovery after the battle.

Northampton was unable to take Morlaix and abandoned the siege.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Morlaix:

- William de Bohun commanded the right flank of King Edward III’s army at the Battle of Halidon Hill against the Scots in 1333, becoming the First Earl of Northampton in 1337.

- Charles of Blois maintained an ascetic religious life. Following his death in 1364, his cousin the French King Charles V began a move to have Charles of Blois canonized. He was finally beatified in 1904.

References for the Battle of Morlaix:

The Hundred Years War by Alfred H. Burne

Trial by Battle, Volume I of the four volume record of the Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption.

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman.

The Hundred Years War by Robin Neillands.

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Sluys

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Auberoche