The naval battle on 22nd June 1372 in the Hundred Years War between the English and the Castilians which saw the complete destruction of the English fleet and of England’s plans for the defence of Gascony against the French

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Najera

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Otterburn

Date:

22nd June 1372.

Place:

The battle took place in the approaches from the Bay of Biscay to the Breton harbour of La Rochelle in western France.

Combatants:

An English fleet against a Castilian fleet.

Admirals:

John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke commanded the English fleet. The Castilian fleet was commanded by the Genoese admiral, Ambrosio Boccanegra.

Size of the navies:

The Earl of Pembroke’s English fleet comprised 14 small ships of not more than 30 tons burden and 3 large fighting ships.

Pembroke’s ships were manned by their normal crews with an additional 80 men-at-arms and 80 archers.

Pembroke was accompanied by a number of Gascon notables, returning to Gascony with their retinues to fight the French, who fought in the battle.

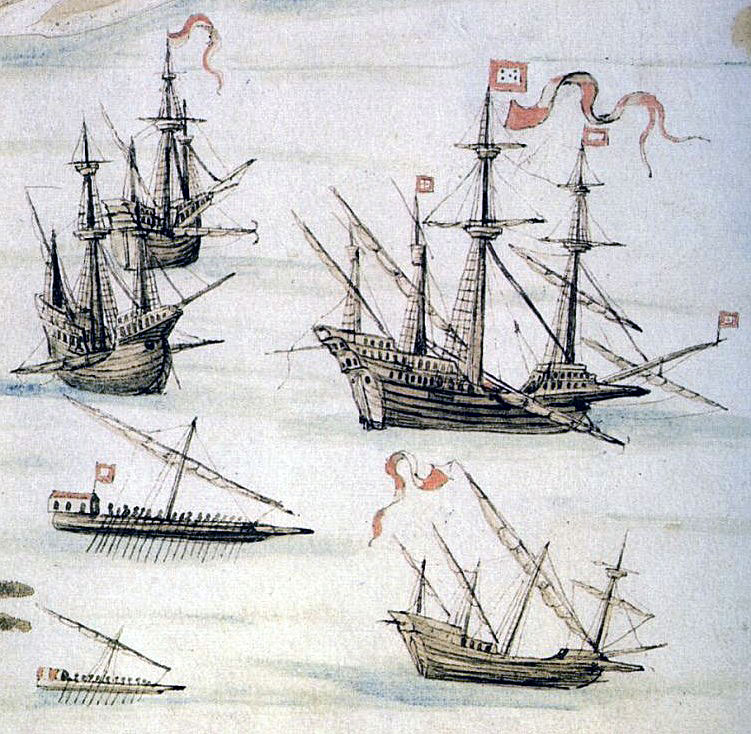

Boccanegra’s Castilian fleet comprised 12 oared galleys and 8 to 10 large carracks or sea-going sailing ships.

The Castilian carracks were significantly larger than most of the English ships, their fighting men being housed in built up structures well above the English fighting platforms, with protective shields for protection against arrows.

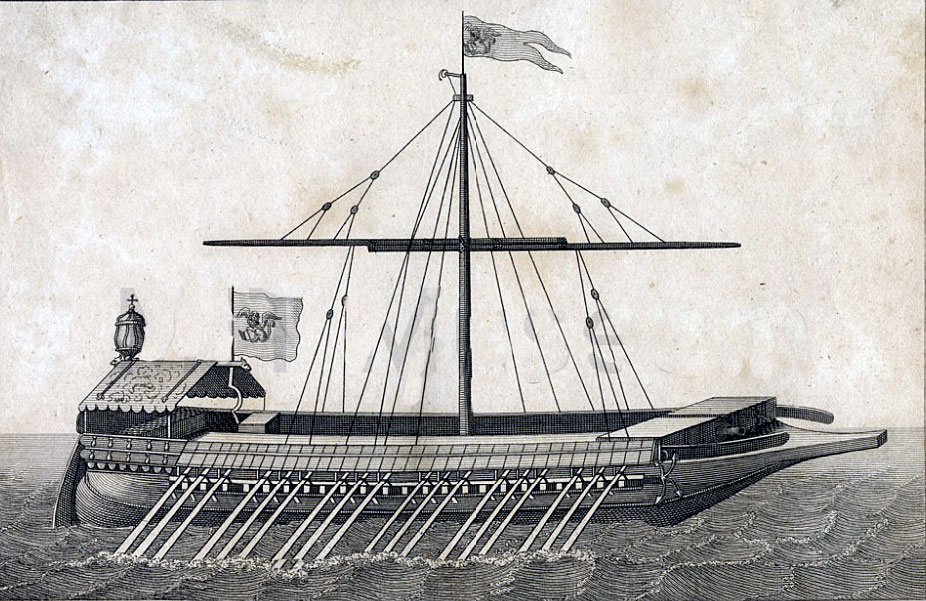

The Castilian galleys, powered by oars were constructed for war and were highly manoeuvrable, particularly in coastal areas.

The Castilian galleys were equipped with fixed arbalests or heavy crossbows and catapults for hurling large stones at opposing ships.

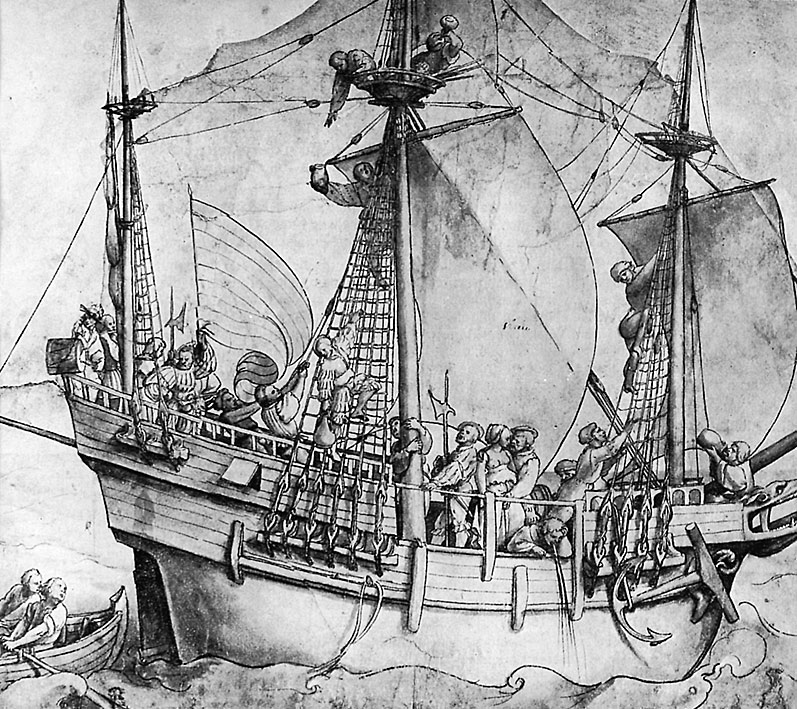

England did not have a dedicated fleet of warships in the 14th Century. In times of war the king called upon the merchant vessels of his subjects and manned them, in addition to their crews, with archers and men-at-arms; converting the ships for war by building forecastles, after castles and crows’ nests, fortifications from which archers directed their fire onto enemy vessels.

These merchant vessels were called Cogs; square rigged and single masted with sharp prows and sterns and steered by an oar or a rudder.

The nearest to a formal English navy was the arrangement the king had with the Kentish towns known as the Cinque Ports. In return for trading privileges the Cinque Ports provided a number of vessels for a period each year for royal military purposes.

In battle, a ship would lay alongside an enemy, decimate her crew with discharges of arrows and showers of heavy stones, leaving the way clear for men-at-arms to board, overcome the survivors and take the ship and its crew.

At the Battle of La Rochelle, the Castilians in their larger caracks were above the English fighting men, protected by the sides of the ship and fired their arrows down on the English.

Winner:

The Castilians captured or destroyed the entire English fleet.

Account of the Battle of La Rochelle:

In the early 1370s, English suzerainty over the western French province of Gascony was threatened by a French incursion led by the Breton commander, Bertrand du Guescelin, Constable of France and the Duke of Bourbon.

In June 1372, the Earl of Pembroke was sent with a small fleet from England to take command of the defence in Gascony.

Pembroke’s fleet comprised some 14 small ships, with an escort of 3 larger ships.

In one of Pembroke’s ships was transported £12,000 in cash to pay his army in Gascony for up to six months.

Although Bordeaux was the capital of Gascony and the base from which the defence of the principality was conducted, it was decided that Pembroke’s destination would be the Breton port of La Rochelle.

Castile, the major Atlantic Sea power of western Europe, was allied with France and a Castilian fleet, commanded by the Genoese admiral, Ambrosio Boccanegra, sailed to La Rochelle and for some two weeks awaited the arrival of Pembroke’s fleet, anchored outside the port.

La Rochelle lies at the head of a wide estuary leading from the Bay of Biscay, with the île de Ré on the north side and the île d’Oléron on the south. Sandbanks on each side make for tricky navigation.

Pembroke arrived outside La Rochelle, unaware that the powerful Castilian fleet awaited him.

As the Castilians sailed out to attack him, Pembroke decided to force his way through to the harbour.

The battle began in the late afternoon of 22nd June 1372.

It seems likely that Pembroke did not grasp the considerable disparity in strength between his fleet and the Castilian.

The Castilian caracks were larger than his ships, other than his three escorts and experienced sailors in his fleet would have warned him of the dangers of fighting the highly manoeuvrable Castilian galleys in the bay.

The war experience of the 24-year-old Earl of Pembroke was on land and it is likely that he was not able to assess the relative strengths of the two fleets and the danger to his ships. In any case, his previous encounters on land suggest that Pembroke was not inclined to take advice from his social inferiors, however necessary.

The catapults on the Castilian galleys enabled them to subject the English ships to a damaging rain of rocks and projectiles before the two fleets closed.

Once the opposing fleets closed, the English could not reach the Castilian men-at-arms and archers in their taller ships.

After several hours of fighting, night fell and the fleets disengaged.

Two English ships had been sunk.

It is said that the Castilian ships took stations for the night that prevented the English ships from making off into the Bay of Biscay.

On the other hand, it may well not have been clear which way the battle was going with Pembroke maintaining his intention to fight his way into La Rochelle the next day.

During the night the English Seneschal of Saintonge, Sir John Harpenden, managed to raise a small reinforcement in La Rochelle, comprising a few barges in which he conveyed a number of Gascon volunteers from neighbouring garrisons out to the English fleet.

The next day the Castilians renewed the battle, led by their caracks.

Several Castilian ships attacked Pembroke’s flagship, pouring oil over its decks and setting it on fire.

Over the course of the next few hours, the whole English fleet was sunk or captured.

Pembroke was forced to surrender.

All the Gascon notables in the English ships were killed or taken, as was Harpenden.

Casualties: It is not known what casualties the Castilians suffered but it is unlikely to have been a great number.

The surviving English prisoners were loaded with chains and taken to the Castilian port of Santander.

In spite of his rank as a royal earl, Pembroke was treated no better than any of the other English prisoners.

Pembroke was incarcerated in Curiel Castle, a Roman fortification near Valladolid, in conditions which broke his health.

In 1374, Pembroke, with a number of other English prisoners, was given to the French Constable, Bertrand du Guescelin, to ransom.

Du Guescelin took Pembroke to France, but the earl died as a result of his treatment at Curiel before du Guescelin could finalise his ransom.

Many other Englishmen from Pembroke’s fleet remained in Castilian captivity for years.

Follow-up:

The sum of £12,000 to pay the Anglo-Gascon troops, carried in an English ship, was lost.

Pembroke, the intended commander for the Anglo-Gascon troops in Gascony, was a prisoner.

Plans for the defence of Gascony against French invasion were thrown into complete disarray.

The Battle of La Rochelle is said by some historians to be England’s worst naval defeat.

References:

The Hundred Years War by Robin Neillands.

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Najera

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Otterburn