The spectacular pre-dawn attack on the British/Indian Army camp at Wana in Waziristan on 3rd November 1894 by 2,000 Mahsud tribesmen, led by the radical Muslim preacher, the Mullah Powindah and the short campaign that followed

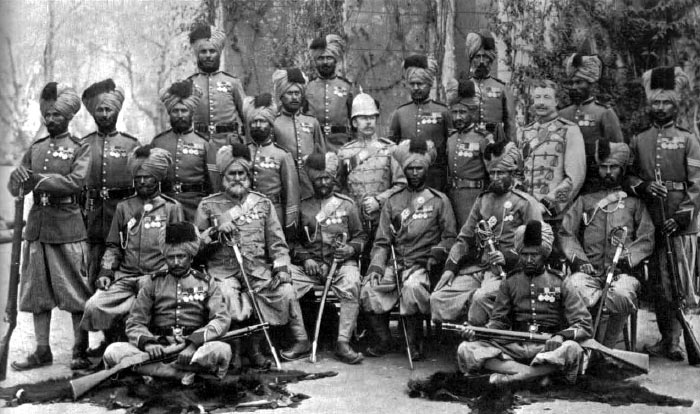

20th Punjab Infantry: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Walter Fane

The previous battle in the North-West Frontier of India sequence is the Black Mountain Expedition 1891

The next battle in the North-West Frontier of India sequence is the Siege and Relief of Chitral

To the North-West Frontier of India index

The Mullah Powindah: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

War: North-West Frontier of India

Date of the 1894 Waziristan Campaign: 3rd November 1894 to March 1895

Place of the 1894 Waziristan Campaign: The independent tribal region of Waziristan, to the south of the Kurram River on the border with Afghanistan.

Commanders in the 1894 Waziristan Campaign: Brigadier-General Turner commanded the Indian Army force surprised in the camp at Wana on 3rd November 1894. Lieutenant-General Sir William Lockhart commanded the Waziristan Field Force that inflicted reprisals on the Mahsud Tribe following the Wana attack. The Mahsud tribesmen that attacked the Wana camp were led by the Mullah Powindah. There was no identifiable Mahsud leadership during the British incursion into Mahsud country.

Size of the forces in the 1894 Waziristan Campaign: The Indian Army force attacked in the camp at Wana numbered around 2,500 men. The three brigades that formed the Waziristan Field Force numbered, in all, around 8,000 men. Probably around 2,000 tribesmen attacked the camp at Wana on 3rd November 1894.

Combatants in the 1894 Waziristan Campaign: Regiments of the British and Indian Army against the Mahsud tribesmen of Waziristan.

Winner of the 1894 Waziristan Campaign: The reputation of the Indian Army took a severe knock by being surprised at Wana. The result of the subsequent campaign was the capitulation of the Mahsuds.

Uniforms, arms and equipment in the 1894 Waziristan Campaign:

The British military forces in India fell into these categories:

-

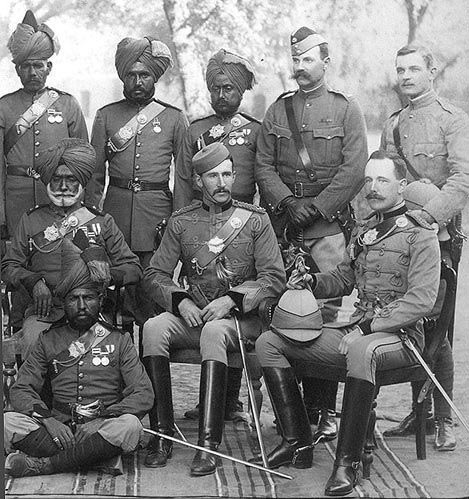

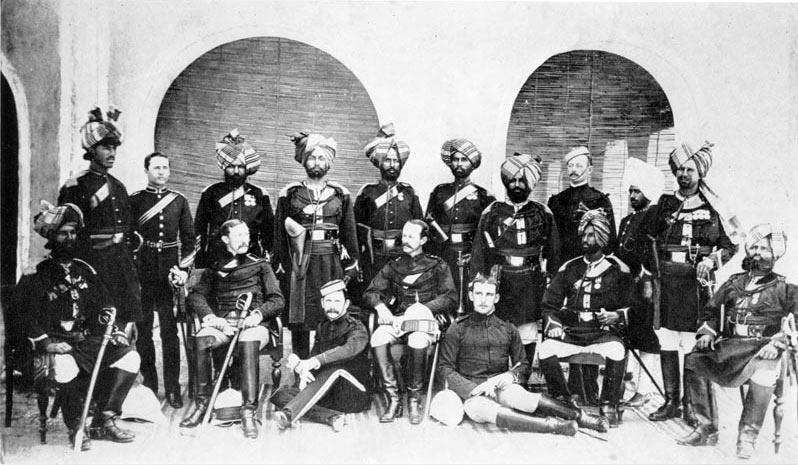

Punjab Frontier Force (‘PIFFERS’) 1st Punjab Regiment, 1st Punjab Cavalry, 3rd Sikhs and Punjab Mountain Battery: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by Richard Simkin

Regiments of the British Army in garrison in India. Following the Indian Mutiny of 1857, India became a Crown Colony. The ratio of British to Indian troops was increased from 1:10 to 1:3 by stationing more British regiments in India. Brigade formations were a mixture of British and Indian regiments. The artillery was put under the control of the Royal Artillery, other than some Indian Army mountain gun batteries.

- The Indian Army comprised the three armies of the Presidencies of Bombay, Madras and Bengal. The Bengal Army, the largest, supplied many of the units for service on the North-West Frontier. The senior regimental officers were British. Soldiers were recruited from across the Indian sub-continent, with regiments recruiting nationalities, such as Sikhs, Punjabi Muslims, Pathans and Gurkhas. The Indian Mutiny caused the British authorities to view the populations of the East and South of India as unreliable for military service.

- The Punjab Frontier Force: Known as ‘Piffers’, these were regiments formed specifically for service on the North-West Frontier and were controlled by the Punjab State Government.

- Imperial Service Troops of the various Indian states, nominally independent but under the protection and de facto control of the Government of India. The most important of these states for operations on the North-West Frontier was Kashmir.

A British infantry battalion comprised 10 companies, with around 700 men and some 30 officers. A battalion possessed a maxim machine gun detachment of 2 guns and some 20 men.

Indian infantry battalions had much the same establishment without the Maxim gun detachment. Senior officers were British, holding Queen’s Commissions, of which a battalion would have 5 or 6. Junior officers were Indian.

In 1894 British and Indian infantry regiments were issued with the single shot drop action Martini-Henry breech loading rifle. The 2nd Border Regiment had just received the new Lee Metford magazine rifle.

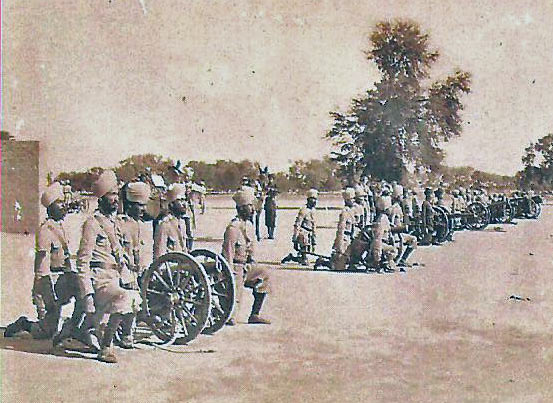

The Indian Mountain Batteries used 7 pounder rifled muzzle loading (RML) guns that were dismantled and carried on mules. These guns were unreliable and difficult to use effectively. The British Mountain Batteries used the more modern 2.3 inch RML guns.

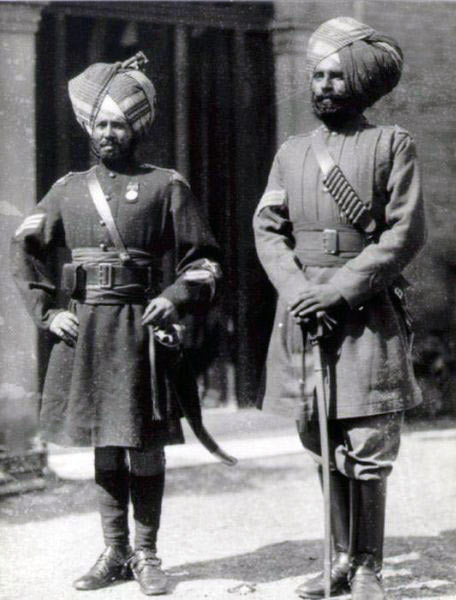

3rd Sikh Infantry: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

British and Indian troops in 1895 wore khaki field dress when campaigning, with a leather harness to carry equipment and ammunition. British troops wore a pith helmet. Indian troops were largely turbaned. Gurkha troops wore a pill box hat.

The Indian cavalry regiments were armed with lance, sabre and carbine.

The standard tactic used by the British and Indian armies on the North-West Frontier of India as with other so-called ‘semi-civilised enemies’ (tribesmen armed with swords and lances and with limited access to modern firearms) was to deliver a frontal assault, discharging controlled volleys of rifle fire and attacking with the bayonet. When under fire and not moving, cover was taken behind sangars or low stone walls. Supporting fire would be provided by artillery. Cavalry conducted scouting duties and, in favourable circumstances, delivered mounted charges.

When a military column moved through hostile country, great care had to be taken to ensure that flanking high ground was occupied in strength, until the column was clear of the area.

Tribesmen: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

The tribesmen were in possession of muskets, jezails, some Snider and a few Martini-Henry rifles. They possessed no artillery or machine guns. The tribesmen were on foot.

A feature of warfare on the North-West Frontier of India was the ability of tribesmen to assemble in large numbers, with little warning and to move at disconcerting speed across mountainous terrain, even at night.

The Mahsuds were notorious for preferring to fight by ambush rather than in open battle.

Tribesmen: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

Background to the 1894 Waziristan Campaign:

Waziristan, an arid and inhospitable mountainous region, hot in summer and snow bound in winter, lies along the Afghanistan border to the south of the Kurram River. It is inhabited by two main Pathan tribes, the Darwesh Khels in the northern part, known as ‘Wazirs’, and the Mahsuds in the south and east, both Wazir tribes. The two other tribes in the area are the Dawaris and the Bhittanis, both less significant and neither Wazir.

The mountains of Waziristan increase in height to the west, providing the watershed between the Indus basin of western India and the Helmond River in Afghanistan.

The principal rivers of Waziristan are the Kurram, Kaitu, Tochi and Gumal Rivers, all flowing from west to east. Many smaller rivers and streams intersect the mountains, finally flowing into one of these four large rivers.

Communications throughout Waziristan lie along the valleys, formed by rivers and nullahs. While many might be dry for much of the year, they could prove dangerous if a storm occurred in the mountains and caused a spate to surge down the valley.

The inhabitants of Waziristan considered themselves to be without a ruler. The Amir of Afghanistan at times claimed suzerainty over the region, but mostly the Amir acknowledged the independence of the area.

In 1893, the British persuaded the Amir to agree to a commission, comprising officers from Afghanistan and British India, to establish the border between Afghanistan and the independent tribal areas. The Amir agreed with considerable reluctance.

The Durand Line: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

The border, known to the British as the ‘Durand Line’, after their commissioner, Sir Mortimer Durand, was to be marked along its length with white posts. Correctly assuming the marking of the border in this way to be a sign of a British intention in due course to annex all the tribal areas, the putting up of border posts was highly objectionable to the Pathan population of Waziristan.

The Government of India appointed a Boundary Commission and Survey party, under the leadership of Mr. R.I. Bruce CIE. The Border Commission established a camp at Wana, in the south of Waziristan, from where it proposed to carry out the work of marking the agreed border.

On 10th October 1894, a jirga from the Ahmadzai of Wana presented a petition from its tribal members asking the British Government to take over Wana and to make the members of the Ahmadzai British subjects.

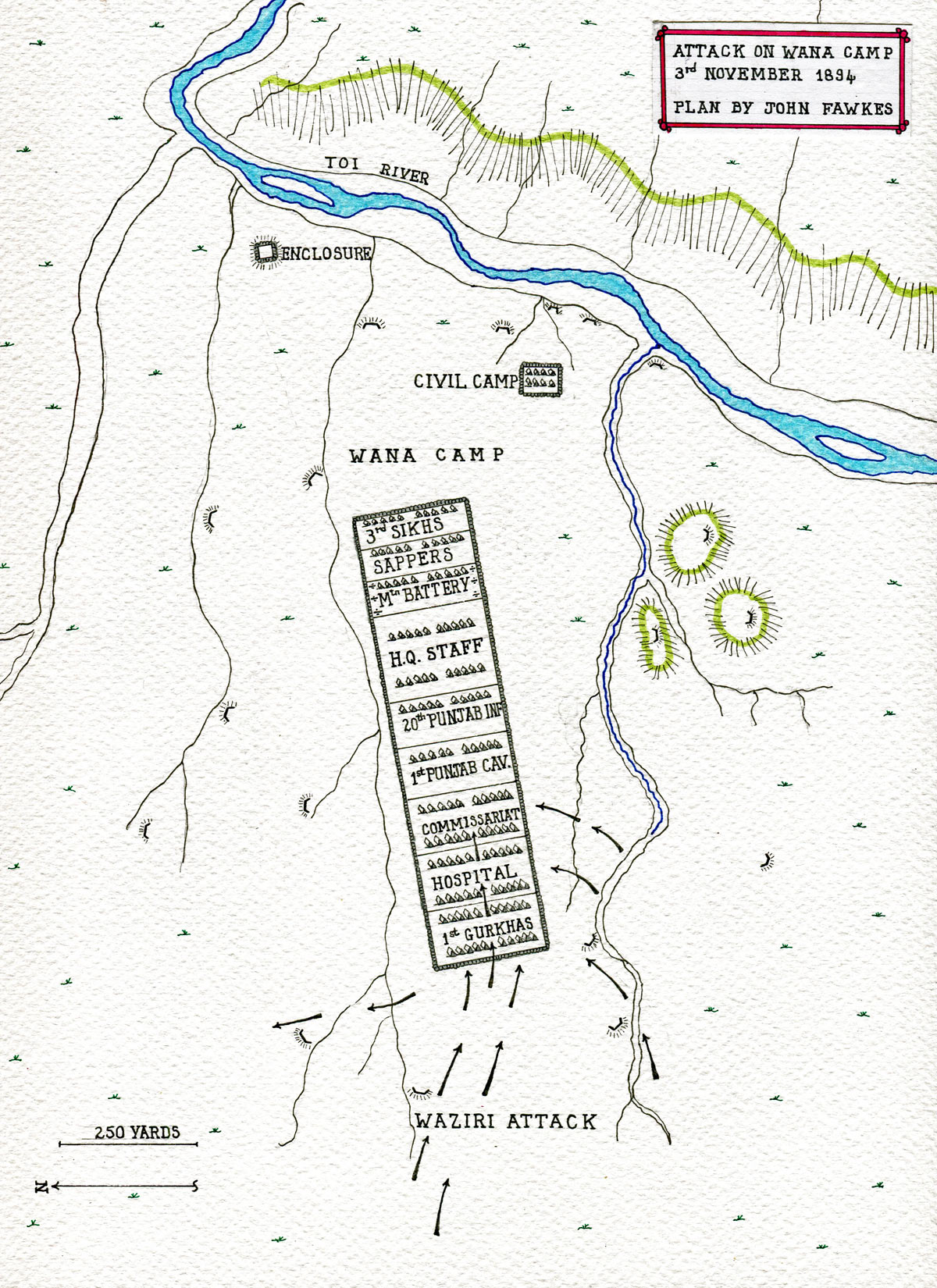

Plan of the Waziri attack on Wana Camp on 3rd November 1894: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India: plan by John Fawkes

Account of the 1894 Waziristan Campaign:

The attack on the camp at Wana:

A strong military escort was allocated to the Border Commission at Wana. This force, denominated the ‘Waziristan Delimitation Escort’, under the command of Brigadier-General Turner, comprised 1 squadron of the 1st Punjab Cavalry, 1st/1st Gurkha Rifles, 3rd Sikh Infantry, 20th Punjab Infantry, No. 3 Punjab Mountain Battery, No. 2 Company, Sappers and Miners and two Native Field Hospitals.

1st Punjab Cavalry: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

Further units were earmarked for a reserve brigade; 2nd Border Regiment at Mooltan and the remainder of 1st Punjab Cavalry, No. 8 Mountain Battery, 4th Punjab Infantry and 38th Dogras at Dera Ismail Khan.

In order to join the Border Commission at Wana, General Turner’s force marched from Dera Ismail Khan to Khajuri Kach, arriving on 18th October 1894.

After investigating water supplies on the various routes, General Turner decided to march to Wana via the area of Spin and Karab Kot.

Punjabi and Dogra Regiments (38th Dogras on the right): Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by AC Lovett

The force marched out on 22nd October 1894, less 20th Punjab Infantry which remained to bring up supplies, moving via the Karkana Kot and the head of Spin Tangi, and arriving at Karab Kot on 23rd October 1894.

On 24th October 1894, General Turner reconnoitred the road to Wana and a post was built at Karab Kot. Shots were fired into the camp that night.

On 25th October 1894, the force marched to Wana, leaving a company of 1st/1st Gurkhas in the new post, with some sappers and miners. At Wana, a jirga of Ahmadzais expressed pleasure at the arrival of the British force. However, shots were again fired into the camp during the night.

The Wana plain is around 13 miles long and 11 miles wide. Wana itself lies at the eastern end of the plain. The official record states that the camp was pitched at this place ‘for political reasons’, without giving those reasons and that the camp was larger than could conveniently be defended because no trouble was expected. This view was confirmed by the arrival at the camp on 27th October 1894 of jirgas from the Nana Khel and the Machi Khel, both Mahsud clans.

1st Kohat Mountain Battery: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

Nevill, in his book, comments that the camp was not fortified in the way usual for a British camp on the North-West Frontier and as required by the British Field Service Regulations. In addition, the camp was positioned near to several dry nullahs, that would give an attacking force a means of approaching the camp in strength without being seen. Nevill also comments that the Mahsud preference for surprise attack over combat in open battle was known to the British military hierarchy. The nature of the camp made the force vulnerable to just such an attack.

20th Punjab Infantry: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

On 28th October 1894, information was received by the British command that a Mullah Powindah was leading a group of Mahsuds, attempting to stir up resistance to the British incursion into Waziristan and trying to prevent the jirgas from going in to negotiate with the British. Mullah Powindah was a cleric of the Shabi Khel clan and had set himself in opposition to the lay maliks of the Mashuds. The information was that Mullah Powindah was approaching Kaniguram to the north-east of Wana with some 800 Mahsuds of various clans with the intention of recruiting more members of the tribe and carrying out hostile action against the British.

On receipt of this information, General Turner withdrew the Gurkhas and Sappers and Miners from Karab Kot and telegraphed for a battalion and 2 guns from the designated reserve to move to Jandola, in the foothills on the Tank River.

On 30th October 1894, a reconnaissance was conducted up the Tiarza Nala, a mountain stream, the direction from which Mullah Powindah was said to be approaching. On the party’s return they were fired on.

On 1st November 1894, information came in to the British, that the Mullah Powindah was at Torwam, on the upper reaches of the Tank River near to the Tiarza Nala, with around 1,000 tribesmen. The Government of India record states that the camp’s piquets were doubled and all ranks ordered to be under arms in their tents by 4am. This precaution, in the event, was far from sufficient.

On 2nd November 1894, a further reconnaissance was conducted in the mountains directly to the north of the camp, in the direction of the Inzar Narai peak. Some shots were fired, but nothing else significant was encountered. On the same day, messages came in from the Mullah Powindah and he was given the answer that all negotiations had to be through tribal jirgas and that he should disperse his Lashkar (a fighting force of tribesmen) and return home. It is recorded that the same precautions were maintained in the camp as on the previous night.

20th Punjab Infantry: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

The camp was not suitable for defence, due to its size and position and had not been fully fortified. Outside the perimeter was a system of support positions and, beyond them, twelve piquets. To the north-east of the camp was a breastwork held by 40 men. In the event of attack, the piquets were to fall back on the support positions and all the outlying troops were to retire to the main perimeter. The one exception was Piquet Hill to the south-west of the camp, where the support position with its two piquets were ordered, in the event of attack, to hold and defend their posts. The reason for this order was that Piquet Hill overlooked the camp. Nevill comments that the orders for the piquets were contrary to usage on the frontier and the requirements of the regulations. Piquets should have been strong enough to maintain their posts when under attack and not to withdraw.

A deserted fort lay 500 yards to the north-east of the camp. This position was held by 100 Gurkhas. Their role in the event of an attack on the camp was to take the attackers in the rear and to cut off their retreat.

3rd Sikh Infantry: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

At 5.30am on 3rd November 1894, in the pitch dark, the camp at Wana was attacked by around 2,000 tribesmen in one of the most dramatic episodes on the North-West Frontier. Three rifle shots rang out (some authorities claim that these shots were a signal for the tribesmen and some a signal from a piquet. Perhaps they were just the first shots).

These shots were immediately followed by wild yells and frenzied drum beating, as tribesmen poured out of the nullahs that had concealed their approach to the camp perimeter. Many of the piquets and support posts raced back to the perimeter as instructed and the wave of tribesmen struck the camp just three minutes after the first warning shots.

The attack fell on the west face of the camp, the encampment of the 1st Gurkhas. The battalion had 4 ½ companies in camp, the remainder being disposed: 1 ½ companies dispersed in the piquets and supports, ¾ company guarding the hospital and 1 ¼ companies in the old fort at the north-eastern approach.

In view of the information received about Mullah Powindah’s group, the British expectation was that any hostile approach would be from the north-east. The suggestions in the authorities are that the British force had begun to build a breastwork at the north-eastern corner of the camp. Even if this is so, the work was inadequate, too late and in the wrong place.

In the attack on the Wana camp, the Mahsuds demonstrated the extraordinary ability of the Pathans to move across mountainous terrain at night and at speed, without being detected. The Lashkar, on reaching the area, circled round to the west of the camp and approached it in the pitch dark by way of two dry nullahs. The assault appears to have been headed by a group of particularly fanatical tribesmen, around 800 in number.

Sappers and Miners: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

A report in the Pioneer Magazine of 9th November 1894 claims to have identified three separate attacks. It seems more likely that the rate of the charge was dictated by the geography of the nullahs, the enthusiasm of individual tribesmen for battle and their capabilities, rather than any intention to form separate attacks.

There seems to have been the initial attack against the western face of the camp, a secondary flow of tribesmen around to the south face of the camp and into the area of the hospital, commissariat and cavalry lines and another flow around the north face, that did not lead to a direct assault, but confined itself to shooting into the camp.

The order that the soldiers be under arms in their tents, if this was the order that was given, was inadequate. Few soldiers of the 1st Gurkhas were able to reach the perimeter to meet the attack. Many encountered the charging tribesmen as they came out of their tents, fighting in the dark, bayonet against sword and shield.

B and E companies of 1st Gurkhas formed up in the middle of the regiment’s lines under Major Robinson and fought to hold back the rush of tribesmen, as they passed through the Gurkha camp into the hospital, commissariat and cavalry lines, slaughtering camp followers and baggage animals. Several horses of the 1st Punjab Cavalry were injured or killed by the tribesmen.

1st Gurkhas: Wana Camp, Waziristan campaign 3rd November 1894 to March 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

F Company, 2nd/1st Gurkhas, attached to the 1st Battalion, reached the perimeter at the north-west corner. A Company, 1st Gurkhas, extended out from the north-west corner of the camp and fired in enfilade into the attacking tribesmen.

A following wave of tribesmen encountered Gurkhas who had fallen back from the support positions on the left and the Regimental Police, some 50 soldiers. Much of this wave lapped around the south face of the camp and entered the lines of the hospital and commissariat.

Lieutenant Colonel William Meiklejohn, commandant of the 20th Punjabis: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

On hearing the burst of firing, the other Indian regiments turned out and manned their sections of the perimeter. It was quickly apparent that the attack was on the 1st Gurkhas and that many tribesmen were on the loose within the camp.

Lieutenant Colonel Meiklejohn, the commandant of the 20th Punjab Infantry and Lieutenant Thompson with 2 companies of the 20th and a company of the 3rd Sikhs under Lieutenant Finnis moved through the camp to reinforce the Gurkhas, bayoneting any tribesmen they encountered.

It would seem that the tribesmen intended a further attack at the north-east corner of the camp, where a group gathered, firing into the perimeter. The mountain guns came into action and fired star shells, lighting up the area. This illumination, with the arrival of dawn, brought the attack to an end and the tribesmen made off to the north-west. The assault on the camp appears to have been over by 6am.

1st Punjab Cavalry: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

With full daylight, the general ordered out the squadron of 1st Punjab Cavalry. Led by Major O’Mealy, 61 troopers of the squadron headed north towards the Inzar Kotal, in pursuit of the tribesmen.

Immediately after the cavalry, Colonel Meiklejohn marched out, at speed, with infantry from 3rd Sikhs and 20th Punjab Infantry. The pursuit followed the tribesmen to the Inzari Pass, leading into Mahsud country. The cavalry were able to catch and kill some 50 tribesmen, over a distance of around eleven miles. The pursuit was abandoned once it was clear that the Mahsud lashkar had dispersed, leaving no worthwhile force to pursue.

British and Indian losses in the attack on Wana Camp were 2 British officers killed, 2 Indian officers and 19 men killed and 5 British officers and 38 soldiers wounded. These casualties were mainly in 1st/1st Gurkhas. Lieutenant Thompson, 26th Punjab Infantry, attached to the 20th Punjab Infantry was wounded. 43 followers were killed or wounded. The attackers made off with a large number of rifles and a substantial sum in cash. More than 100 baggage animals were killed or injured.

The estimate of the numbers of Mahsud attackers was around 2,000, although only half actually pressed the assault on the camp, while the rest provided covering fire or were part of the attack on the north-east of the camp, which was abandoned. The tribesmen’s casualties were estimated at around 100 killed in the attack, with a further 50 killed by the cavalry in the pursuit.

The campaign following the Wana Camp attack:

The Indian Government was presented with a considerable problem by the Wana incident. It was apparent that the attack was planned and executed by the Mullah Powendah, over whom the mainstream Mahsud tribal leaders had no control. On the other hand, the attack was a spectacular success for the tribesmen and left a significant dent in British prestige. Some form of retribution against the Mahsuds was considered essential.

The Mahsud maliks were offered terms, which involved the supply of hostages, the expulsion of the Mullah Powindah from Waziristan until the boundary marking was complete and the return of the loot taken in the attack on 3rd November 1894. The period for compliance was given and extended to 12th December 1894.

In the meantime, a Waziristan Field Force was formed, to conduct punitive incursions against the Mahsuds, in case the terms were not complied with.

The Waziristan Field Force, under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir William Lockhart, comprised:

First Brigade; the Delimitation Escort under this new denomination, with the addition of 2nd Border Regiment;

Second Brigade at Tank, commanded by Brigadier-General W. Penn Symons comprising 1 squadron each of 1st and 2nd Punjab Cavalry, 33rd Punjab Infantry, 38th Dogras, 4th Punjab Infantry, 1st/5th Gurkhas, No. 8(B) Mountain Battery, No. 5 Company Bengal Sappers and Miners and 1 Maxim Gun;

Third Brigade at Mirian, commanded by Colonel C. C. Egerton, comprising 3rd Punjab Cavalry, 1st Sikh Infantry, 2nd Punjab Infantry, 6th Punjab Infantry and No. 1 Kohat Mountain Battery.

By 11th December 1894, it was apparent that the Mahsud maliks could not comply with the terms offered, mainly because they had no hold over the Mullah Powindah and could not recover the captured rifles and money.

On 16th December 1894, General Lockhart, after taking over command of the area, received orders for his three brigades to advance into Mahsud country.

The First Brigade was joined by 1st/4th Gurkhas, left a fortified post at Wana in a village rented from the locals and marched to Kaniguram, conducting reconnaissance and survey work, as was the practice on such marches.

General Lockhart accompanied the Second Brigade to the Mahsud town of Makin, on the way destroying the village of the Mullah Powindah, Marobi. There was random shooting, but no significant resistance.

The Third Brigade marched from Bannu to Razmak. All three brigades combined at Makin, on 22nd December 1894, where plans were put in place to attack the Mullah Powindah in the area of Pir Ghal, with 6 columns.

This operation was carried out on Christmas Day, 25th December 1894, with little opposition and a trawl of cattle seized and villages burnt. Thereafter, the three brigades made their way back to Jandola by various routes, burning villages considered to belong to hostile Mahsud elements. Reports were received that the Mullah Powindah was across the border in Afghanistan, unsuccessfully attempting to persuade the Kabul Khel to attack the British forces.

1st Punjab Cavalry: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

On 19th January 1895, General Lockhart issued a final demand for surrender on terms to the Mahsuds and directed the jirgas to assemble at Kundiwam.

The three brigades again marched through Mahsud country, the First Brigade returning to Wana, the Second Brigade, with the general, marching to Kaniguram and the Third Brigade returning to Mirian. Each force conducted reconnaissance, survey work and established telegraph lines and some armed posts, all regular practices in British incursions into independent tribal country in the 1890s and marking the new ‘Forward Policy’ of the Indian Government.

The jirgas arrived as directed and a settlement was negotiated. The Border Commission resumed the work interrupted by the attack on the Wana Camp, with the assistance of tribal representatives. A permanent post was established at Wana. General Sir William Lockhart carried out a reconnaissance in the Tochi Valley, which he assessed as being of greater significance than the Wana area. The operation was deemed complete by the end of March 1895 and the Waziristan Field Force dispersed, leaving a significant British presence in the area.

Incidents of violence against British officials, officers and Indian troops continued until the outbreak of the general tribal war in 1897.

Indian Order of Merit: Waziristan campaign 3rd November 1894 to March 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Casualties in the 1894 Waziristan Campaign:

The casualties in the attack on Wana Camp are given in the text above. The casualties in the remaining operations were not significant.

Battle Honour and decorations for the 1894 Waziristan Campaign:

There was no battle honour for this campaign.

All ranks received the Indian General Service Medal, with the clasp ‘Waziristan 1894-5’. As was the practice, the civilians in the Force received the same medal and clasp, in bronze rather than silver.

Lieutenant Colonel Meiklejohn was appointed Commander of the Bath.

Eight soldiers of 1st/1st Gurkha Rifles were awarded the Indian Order of Merit Third Class for the action at Wana.

Follow-up to the 1894 Waziristan Campaign:

The surprise attack on the camp at Wana was a substantial embarrassment to the Indian Army.

It is far from clear to what extent the Wana Camp was fortified in time for the assault on 3rd November 1894. The Historical Records of the 20th Punjab Infantry describe the regiment’s soldiers as manning the ‘breastwork’. The Government of India record refers to a ‘breastwork’. Nevill’s commentary on the battle makes it clear that there was inadequate compliance with the Field Service Regulations, in terms of fortifying the camp. Nevill also criticizes the positioning of the camp near to the nullahs. There appears to have been a concern on the part of contemporary recorders of events to limit criticism of the authorities.

Indian General Service Medal 1854 with the clasp ‘Waziristan 1894-5’: Waziristan campaign 3rd November 1894 to March 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

It would seem that the following criticisms are appropriate:

- The military camp was situated near to the Boundary Commission camp, which was itself located for convenience rather than the need for defence.

- The situation of the military camp was inappropriate, due to the presence nearby of several dry nullahs or ravines, which enabled the hostile force to approach close to the camp in cover and unseen. On the other hand, the Wana Plain appears to have been covered in dry nullahs and it was probably not possible to locate the camp away from them all, in which case, strong piquets should have been posted, specifically to supervise each nullah that was dangerously close.

- The area of the camp was too large. The perimeter could not be fortified adequately by the number of troops and there were insufficient troops to man the perimeter effectively in the event of an attack. The distances from many of the tents to the perimeter were too great to enable the occupants to reach their alarm posts quickly.

- The camp did not have adequate fortification, which would have required a stone ‘sangar’ wall and, ideally, an external ditch erected around the perimeter of the camp. This clearly was not done, although there may have been a ‘breastwork’ in parts of the perimeter, particularly at the north-east corner.

- A sensible precaution would have been to post piquets at the head of each of the nullahs. There were some 12 piquets around the camp, although none appeared to be located to watch the nullahs effectively.

- While there are references to precautions being increased in the period 1st to 2nd November 1894 in various accounts, the precautions are either not specified, contradictory, or to no apparent purpose. William Robertson in his memoirs, ‘From Private to Field-Marshal’, records the troops as being caught asleep in their tents. Robertson was, at the time of the attack, on the staff of the intelligence unit responsible for the North-West Frontier and will have read or heard many of the accounts of what happened in the attack, including official reports. Robertson’s memoirs were published in 1921, when he was a field-marshal and in retirement. Robertson will have felt little need to conceal the true events, in what was by then an incident of little significance.

- All the sources agree that the surprise attack was repelled due to the steadiness of the Indian Army regiments in the camp: 1st Gurkhas, 20th Punjab Infantry, 1st Punjab Cavalry, No. 3 Punjab Mountain Battery, No. 2 Company, Sappers and Miners and 3rd Sikh Infantry.

1st Punjab Cavalry: Waziristan campaign, 3rd November 1894 to March 1895, on the North-West Frontier of India

Anecdotes and traditions from the 1894 Waziristan Campaign:

- The Mullah Powindah continued to preach ‘jihad’ against the British in Waziristan throughout the 1890s, operating in the Tochi Valley. He appears to have died in 1913.

- The 1st Gurkhas became the 1st King George V’s Own Gurkha Rifles (the Malaun Regiment) in 1910. With independence in 1947, the Regiment was allocated to India and became the 1st Goorkha Rifles (the Malaun Regiment).

- The 20th Punjab Infantry was a Bengal Army Regiment. In 1903, it became the 20th (Duke of Cambridge’s Own Infantry) (Brownlow’s Punjabis) in the combined Indian Army list. In 1922 the Regiment became 2nd Battalion (Duke of Cambridge’s Own) (Brownlow’s) 14th Punjab Regiment. In 1947 the Regiment became part of the Pakistan Army as 6th Battalion, the Punjab Regiment. The Regiment fought in many of the campaigns on the North-West Frontier of India and was highly experienced.

- Lieutenant Colonel Meiklejohn, the commandant of the 20th Punjab Infantry at Wana, ended his military career as Major-General Sir William Meiklejohn. As a brigadier-general, Meiklejohn was in command at Malakand, when the garrison was attacked by tribesmen in 1897.

- The 3rd Sikh Infantry was a Punjab Frontier Force regiment (‘Piffer’) made up of Sikhs, Dogras, Pathans and Punjabi Muslims. In 1903 the Regiment became 53rd Sikhs (Frontier Force) in the combined Indian Army list. In 1922 the Regiment became 3rd Battalion (Sikhs) 12th Frontier Force Regiment. In 1947 the Regiment was allocated to the Pakistan Army, becoming 5th Battalion Frontier Force Regiment and losing its association with the Sikhs.

- The 1st (Prince Albert Victor’s Own) Punjab Cavalry was a Punjab Frontier Force regiment (‘Piffer’). In 1903 the Regiment became 21st Prince Albert Victor’s Own Cavalry, Frontier Force and in 1922, on amalgamation, 11th Prince Albert Victor’s Own Cavalry (Frontier Force). In 1947 the Regiment was allocated to the Pakistan Army becoming 11th Cavalry (Frontier Force). Prince Albert Victor was the son of the Prince of Wales and a grandson of Queen Victoria. He died of influenza on 14th January 1892. The Prince made a state visit to India from 1889 to 1890, when he accepted the honorary colonelcy of 1st Punjab Cavalry.

Memorial in St. Cuthbert’s Church, Aldingham, Cumbria, to Lieutenant Percy Macaulay, Royal Engineers, killed at Wana Camp, 3rd November 1894, Waziristan, on the North-West Frontier of India

References for the 1894 Waziristan Campaign:

The authority for campaigns on the North-West Frontier of India and other campaigns involving the Indian Army in the 19th Century is the Indian Government publication ‘Frontier and Overseas Expeditions from India’. Six volumes were published around 1905 and distributed internally, primarily to Indian Army Officers and Officials. Volume II covers the Wana/Waziristan Campaign 1894, being the volume on operations south of the Kabul River.

North West Frontier by Captain H.L. Nevill DSO, RFA

Historical Records of the 20th (Duke of Cambridge’s Own) Infantry, Brownlow’s Punjabis.

The previous battle in the North-West Frontier of India sequence is the Black Mountain Expedition 1891

The next battle in the North-West Frontier of India sequence is the Siege and Relief of Chitral

To the North-West Frontier of India index