The siege and relief of the fort at Chitral in the remote mountainous region beyond the North-West Frontier of India, held by Sikh and Kashmiri soldiers and their British officers from 3rd March to 20th April 1895; that caused such a stir in late Victorian Britain

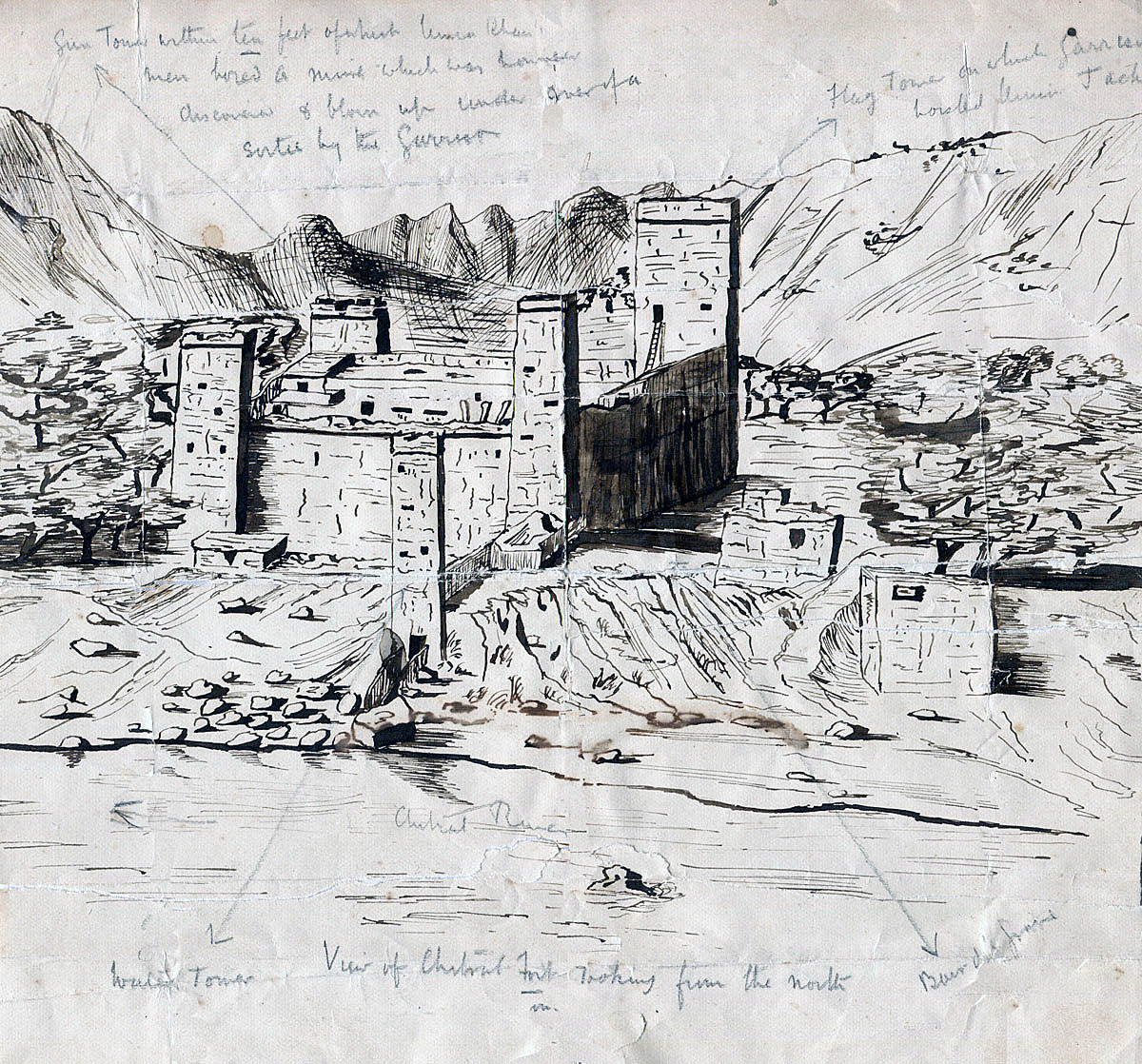

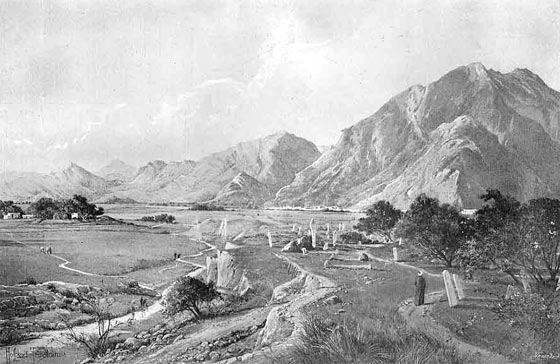

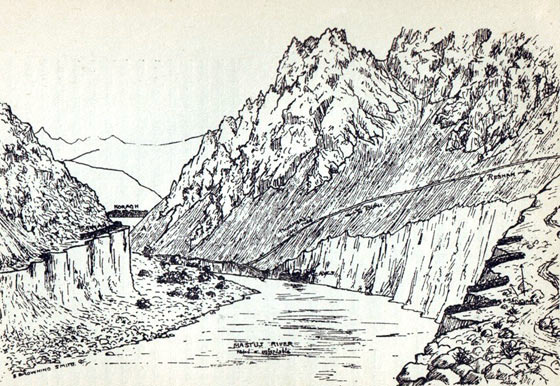

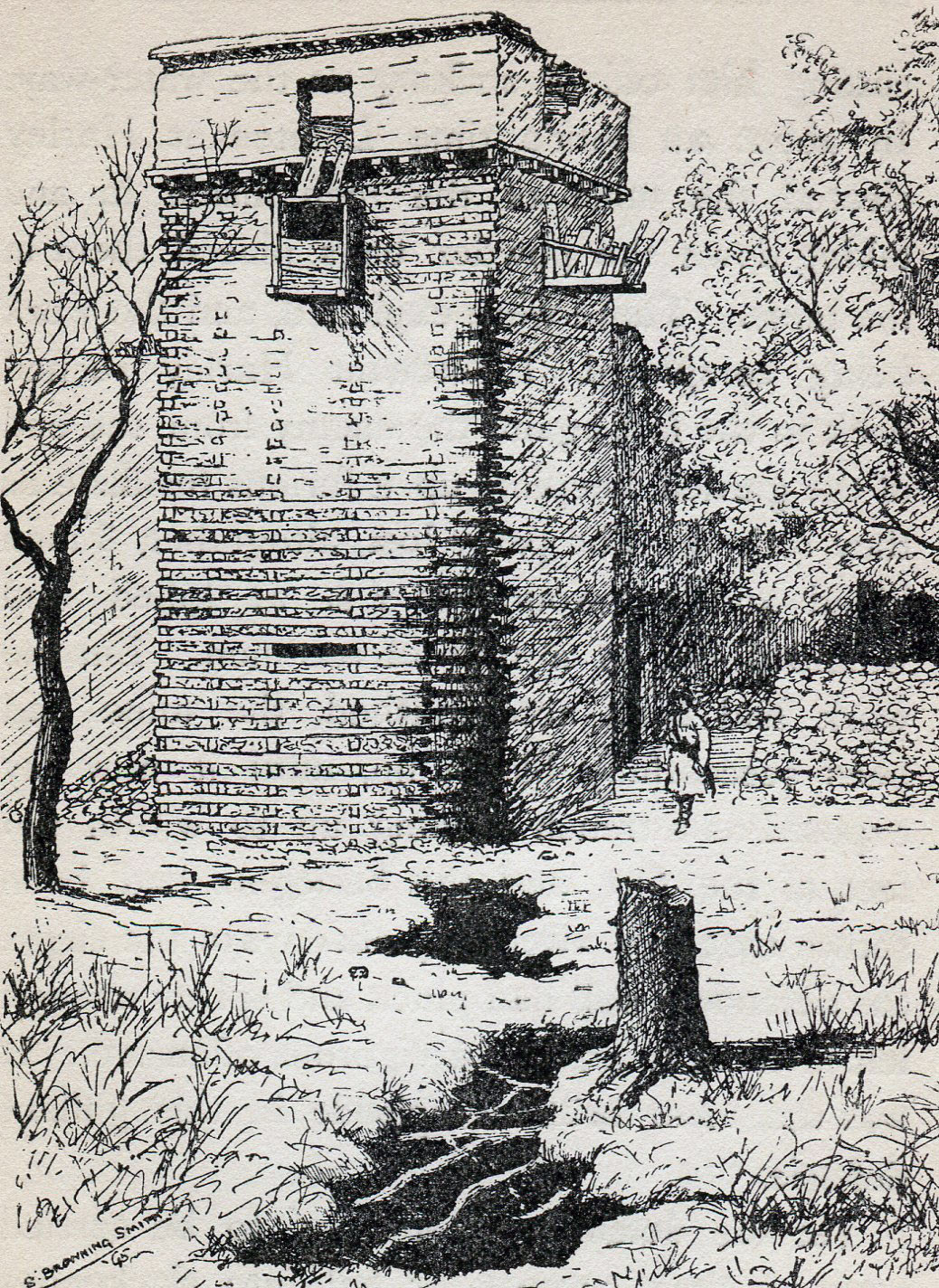

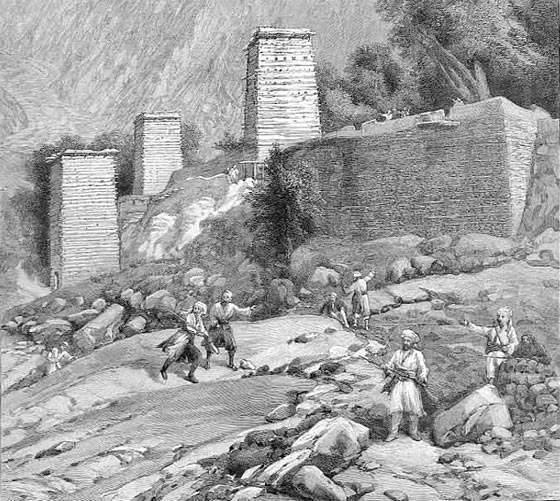

Sketch of Chitral Fort from the far side of Kunar River looking south to the fort, drawn within days of the end of the siege by an officer of the Chitral Relief Force: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India:

Pencil Notes: a. Gun Tower within ten feet of which Umar Khan’s men bored a mine which was however discovered and blown up under cover of a Sortie by the Garrison.

b. Flag Tower on which garrison hoisted Union Jack

c. Water Tower; d. Baird’s grave

e. View of Chitral Fort looking from the north

The previous battle of the North-West Frontier of India is Waziristan 1894

The next battle of the North-West Frontier of India is the Malakand Rising 1897

To the North-West Frontier of India index

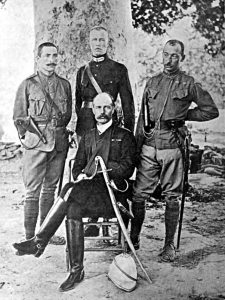

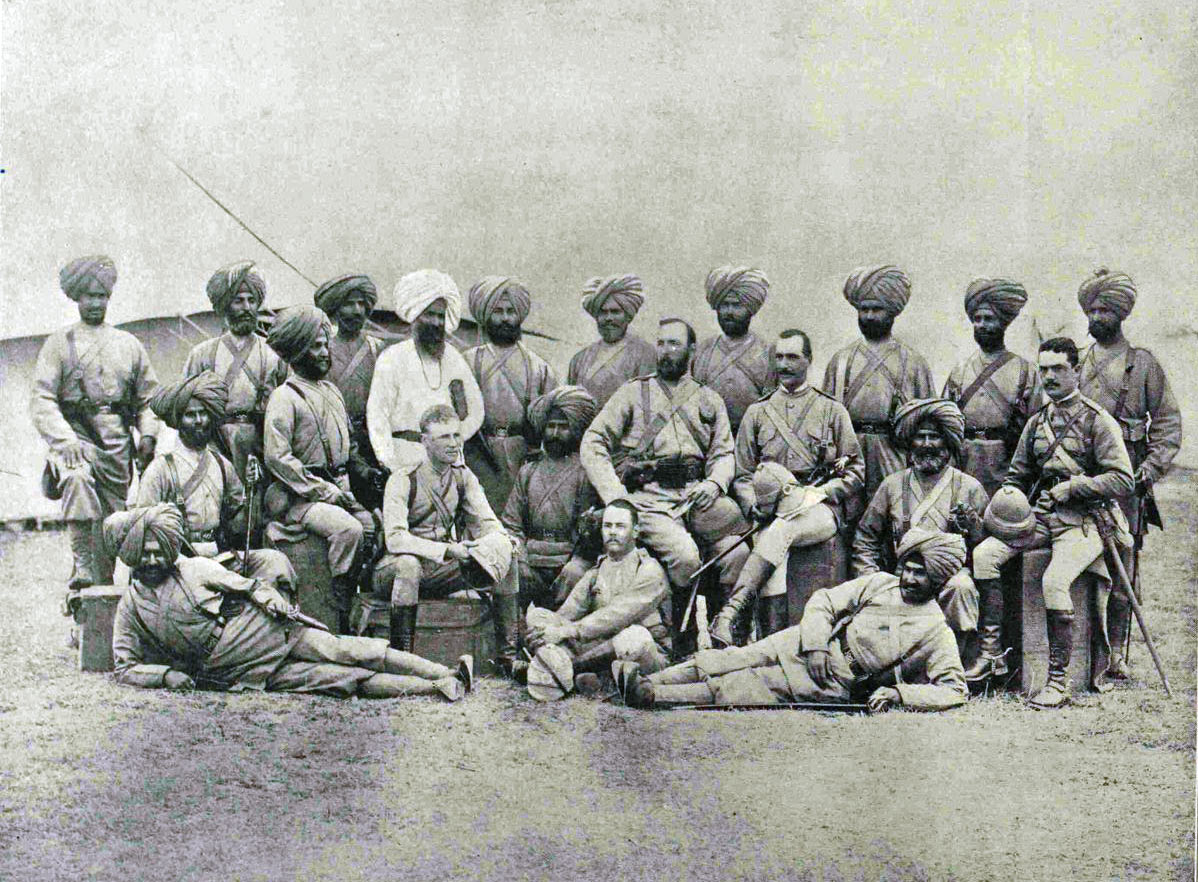

Surgeon Major Robertson (seated) with Lieutenants Harley, Gurdon and Captain Townsend: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

War: North-West Frontier of India.

Date of the Siege and Relief of Chitral: 3rd March to 20th April 1895.

Place of the Siege and Relief of Chitral: Chitral, now in Northern Pakistan.

Contestants in the Siege and Relief of Chitral: British Army, Indian Army, Kashmir Imperial Service Troops and levies from Hunza and Nagar against Chitralis, Jandolis, Afghans and Pathan tribes from the area to the north of the Kabul River.

Commanders in the Siege and Relief of Chitral:

Surgeon Major George Robertson, Indian Medical Service, commanded the Indian Army garrison in Chitral Fort; Lieutenant Colonel Kelly, the commandant of the 32nd Punjab Pioneers, commanded the relief column from Gilgit and Major General Sir Robert Low commanded the relief column from Peshawar against Umra Khan, the Khan of Jandoli and Dir, and Sher Afzul, putative Mehtar of Chitral.

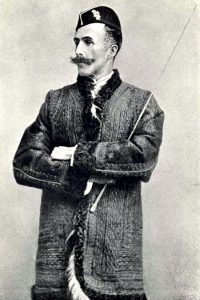

Umra Khan of Jandol: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Size of the forces in the Siege and Relief of Chitral:

The garrison in Chitral from 3rd March 1895 when the siege began comprised some 500 Sikh and Kashmir troops (the exact numbers are set out in the text).

The Chitral Relief Force comprised some 15,000 British and Indian troops, some 9,000 civilian followers and 30,000 transport animals, mules and camels.

Colonel Kelly’s relief force from Gilgit comprised some 500 men of his own regiment, the 32nd Punjab Pioneers, and levies from Hunza and Nagar with a 2 gun section from 1st Kashmir Mountain Gun Battery.

Umra Khan is thought to have invaded Chitral in January 1895 with 4-5,000 men, a number which increased over the following months, until the Chitral Relief Force began operations in the Malakand Pass, when many of Umra Khan’s men left Chitral to oppose the British incursion.

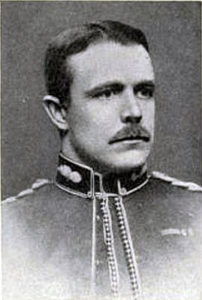

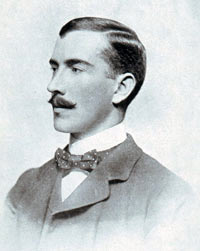

Captain Charles Townsend, senior military officer: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

A wide range of tribes opposed General Low’s Chitral Relief Force, so that the number of tribesmen taking part in the initial fighting, defending the Morah, Shakot and Malakand Passes, was around 20,000. This number decreased after the Malakand Pass was forced and the British took active steps to reassure the tribes that the aim of the force was to relieve Chitral and not to invade their territory. The return of the Khan of Dir assisted in this process. The overthrow of Umra Khan was a not unwelcome outcome for many of the tribes, who felt threatened by Umra Khan’s expansion of his dominion during the 1880s and 1890s.

The number of besiegers of Chitral Fort is not capable of being assessed and varied widely during the course of the siege. There were probably, at any one time, around 2,000 to 5,000 Chitralis, Jandolis, Afghans, Pathans and members of Umra Khan’s army conducting the siege. Many of these men went up the Chitral Valley to attack Edwardes and Fowler’s party and Ross’s Sikhs and later to oppose the advance of Colonel Kelly’s Gilgit Relief Force and then returned.

Winner in the Siege and Relief of Chitral: The British, Indian and Kashmiri forces.

Uniforms and equipment in the Siege and Relief of Chitral:

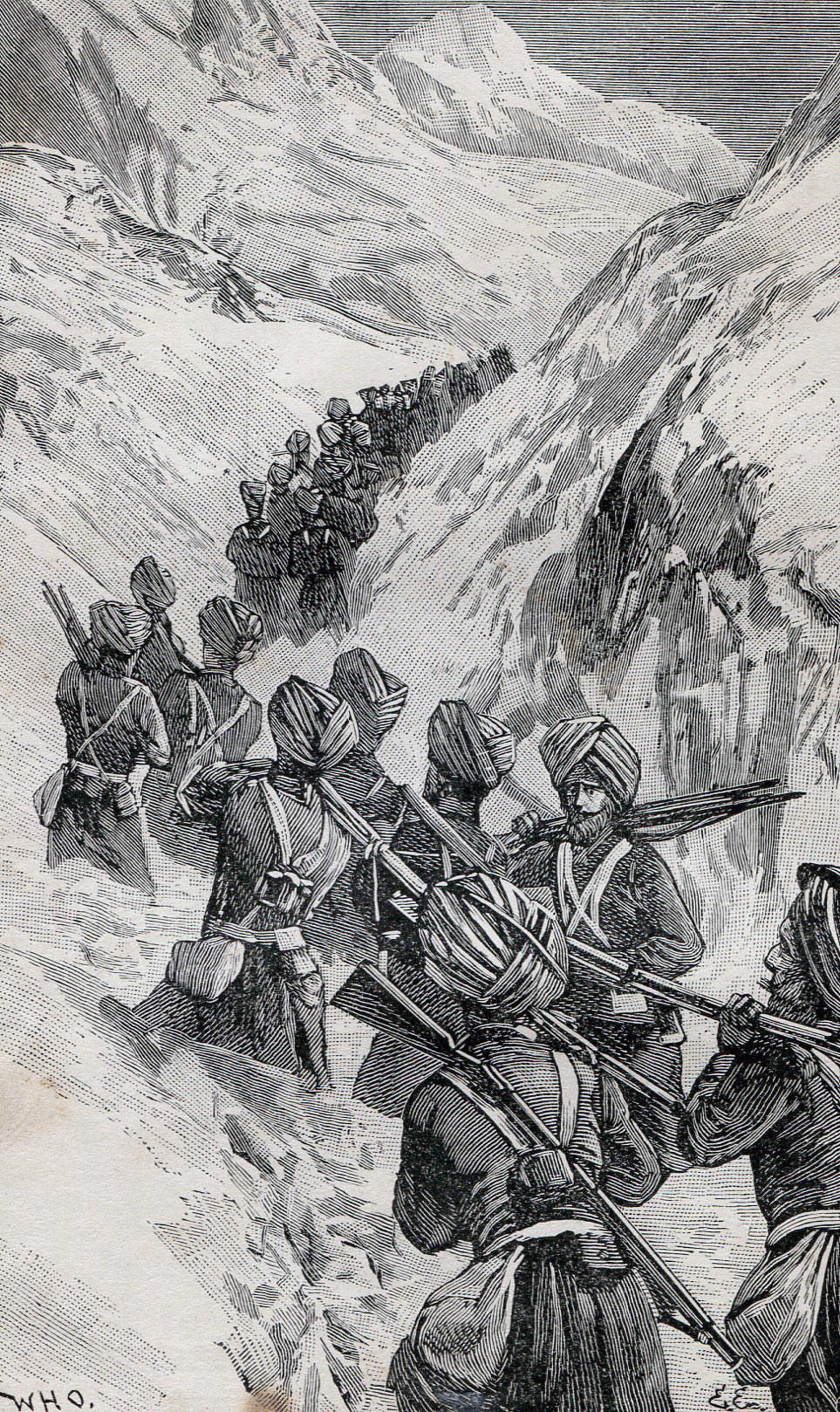

British and Indian troops in 1895 wore khaki field dress when campaigning, with a leather harness to carry equipment and ammunition. British troops wore a pith helmet. Indian troops were largely turbaned. Gurkha troops wore a pill box hat. Highland regiments wore the kilt in the field.

Major General Sir Robert Low, commander of the Chitral Relief Force: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The British authorities operated a system whereby the most modern rifles, Lee-Metford magazine weapons, were made available to the British regiments (none available to the Chitral garrison, but widely issued to the British regiments in Low’s Chitral Relief Force). The Indian army regiments were equipped with an earlier model of rifle, the Martini-Henry (the highly effective drop-action, single shot rifle, withdrawn from service with the British regiments in the 1880s), while the Kashmir soldiers and the levies were equipped with an even earlier model, the Snider (the conversion of the Enfield rifled musket to an inefficient breach-loading rifle in the 1860s). This was a legacy of the Indian Mutiny, as was the system whereby all the artillery, other than some mountain gun batteries, was controlled by the British Royal Artillery.

British Infantry battalions each had 2 Maxim machine guns.

The main artillery support for the British forces on the North-West Frontier of India was the mountain batteries, although there was one field battery in the Chitral Relief Force. The mountain guns were dismantled and carried on mules while in transit.

The two Indian cavalry regiments (11th Bengal Lancers and the Guides Cavalry) were armed with lance, sabre and carbine.

Rissaldar-Major, 11th King Edward’s Own Lancers, Probyns: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by AC Lovett

The standard tactics used by the British and Indian armies on the North-West Frontier of India as with other so-called ‘semi-civilised enemies’ (tribesmen armed with swords and lances and with limited access to modern firearms) was to deliver a frontal attack, discharging controlled volleys of rifle fire and attacking with the bayonet. When under fire and not moving, cover was taken behind sangars. Supporting fire would be provided by artillery. Cavalry would conduct reconnaissance and in favourable circumstances deliver mounted charges.

When a military force moved through hostile country great care had to be taken to ensure that flanking high ground was occupied in strength, until the force was clear of the area.

Umra Khan possessed a semi-disciplined army. Otherwise, the opposition to the British was by tribesmen. Umra Khan’s men were in part equipped with Snider and Martini-Henry rifles. The tribesmen were in possession of muskets, jezails, some Sniders and a few Martini-Henry rifles. Many of the tribesmen, being without firearms, carried swords and knives and resorted to throwing stones or rolling rocks down the mountainside. There were no artillery or machine guns. The tribesmen were largely on foot, although some were mounted.

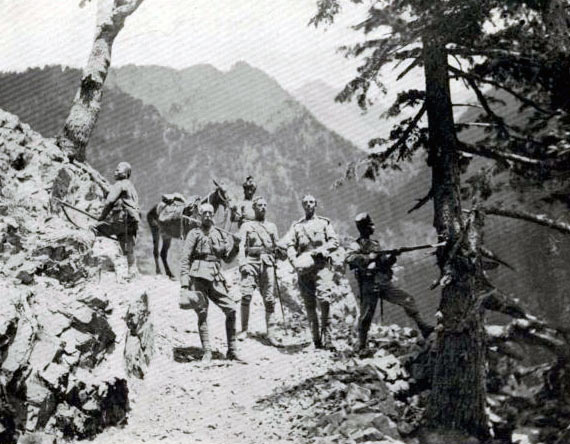

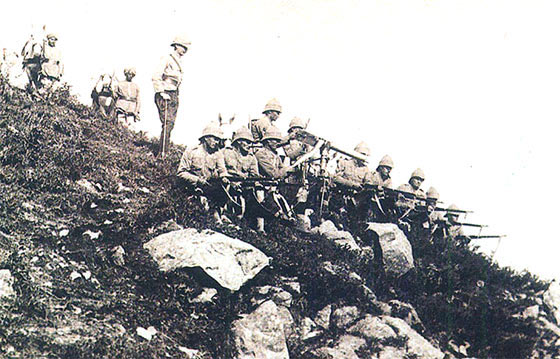

Tribal prisoners taken during the storming of the Malakand Pass: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

A feature of warfare on the North-West Frontier of India was the ability of tribesmen to assemble in large numbers, with little or no warning and to move at disconcerting speed across mountainous terrain.

Jandoli soldier: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Background to the Siege of Chitral:

In the early 1890s Chitral was an independent area to the north-west of Kashmir. Chitral’s northern border ran with Russian Tajikistan, in the area of the Pamirs known as the ‘Roof of the World’, separated from Russia by a thin tongue of Afghanistan.

The whole of Chitral comprised mountainous areas and fast-flowing rivers. The few inhabitants, estimated at that time to be around 55,000, lived on the limited areas of soil alongside the rivers. Communication was along the side of these rivers, in places by way of precarious footways. In places where the rivers ran between steep cliffs, the paths were made by inserting short wooden beams into crevices in the rock and covering them with flat stones and wood. Such paths might be only two or three feet wide and be above a drop of some distance into the torrent beneath. These routes were easily destroyed or defended by a hostile population.

In many areas of Chitral the snow is nearly constant. In the winter months, there are heavy snow falls and many mountain passes become inaccessible. During the day, the sun is often hot and glaring, while the nights are freezing cold. Due to the altitude, the effective period of summer is only a couple of months.

In the 1890s, the ruler of Chitral was entitled the ‘Mehtar’. Chitrali society comprised the Adamzada or minor squirearchy, the middle class, called the Arabzada and the peasantry or Fakir Miskin. The people of Chitral were Muslim. In the higher regions, the pre-dominant sect gave allegiance to the Agar Khan. In the lower areas, the prevailing Islamic sect was Sunni.

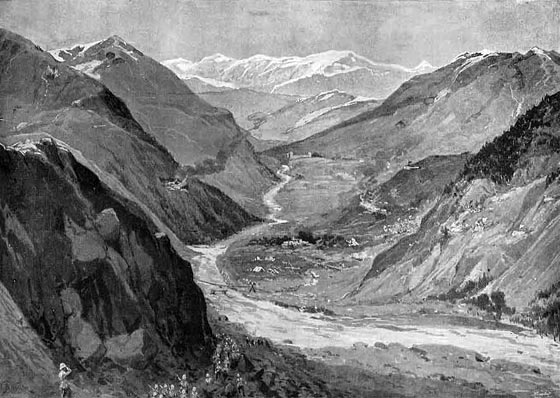

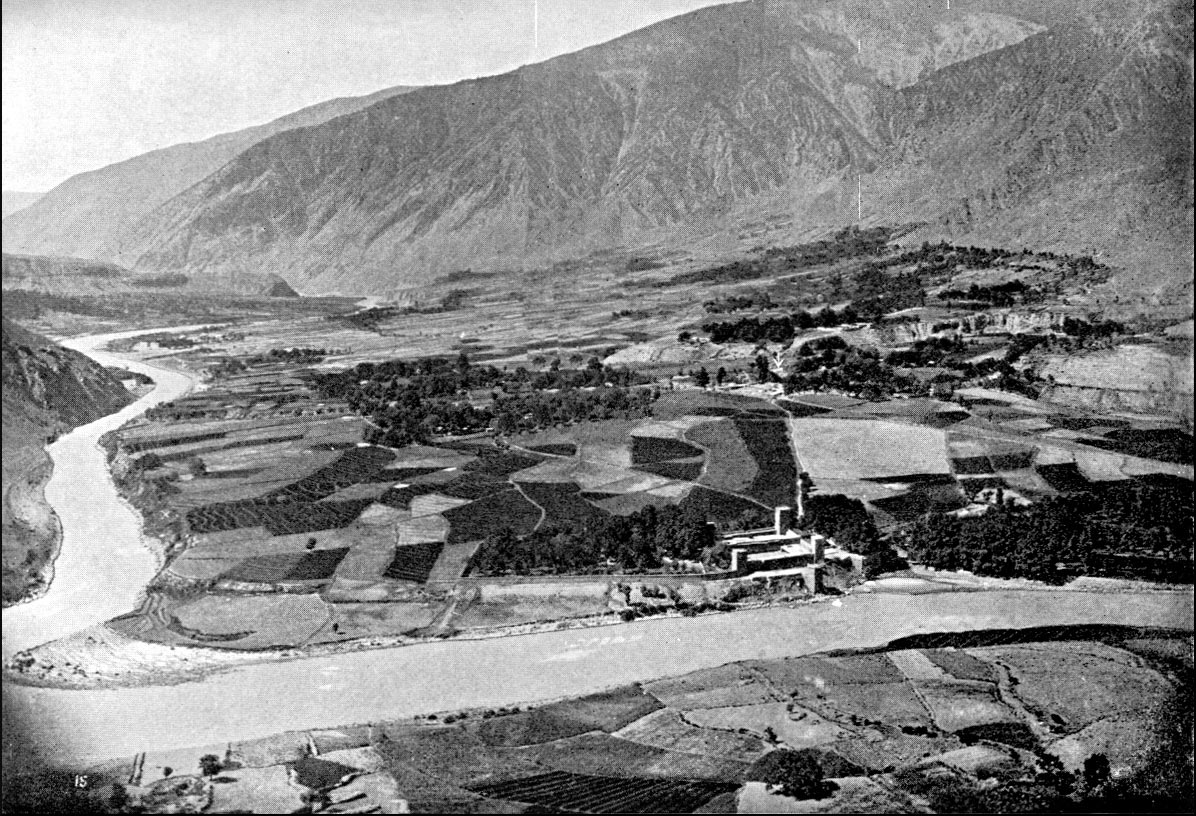

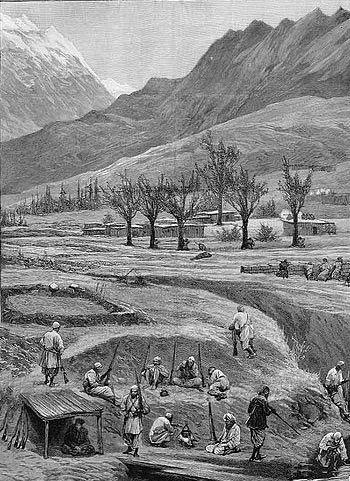

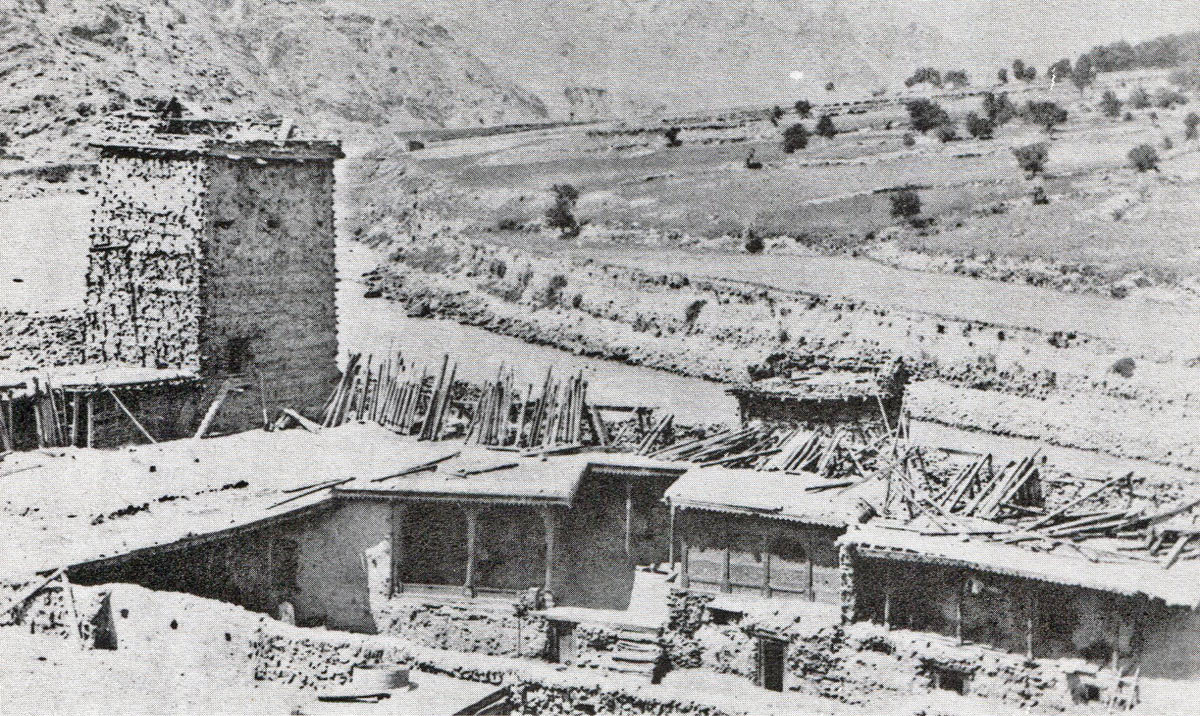

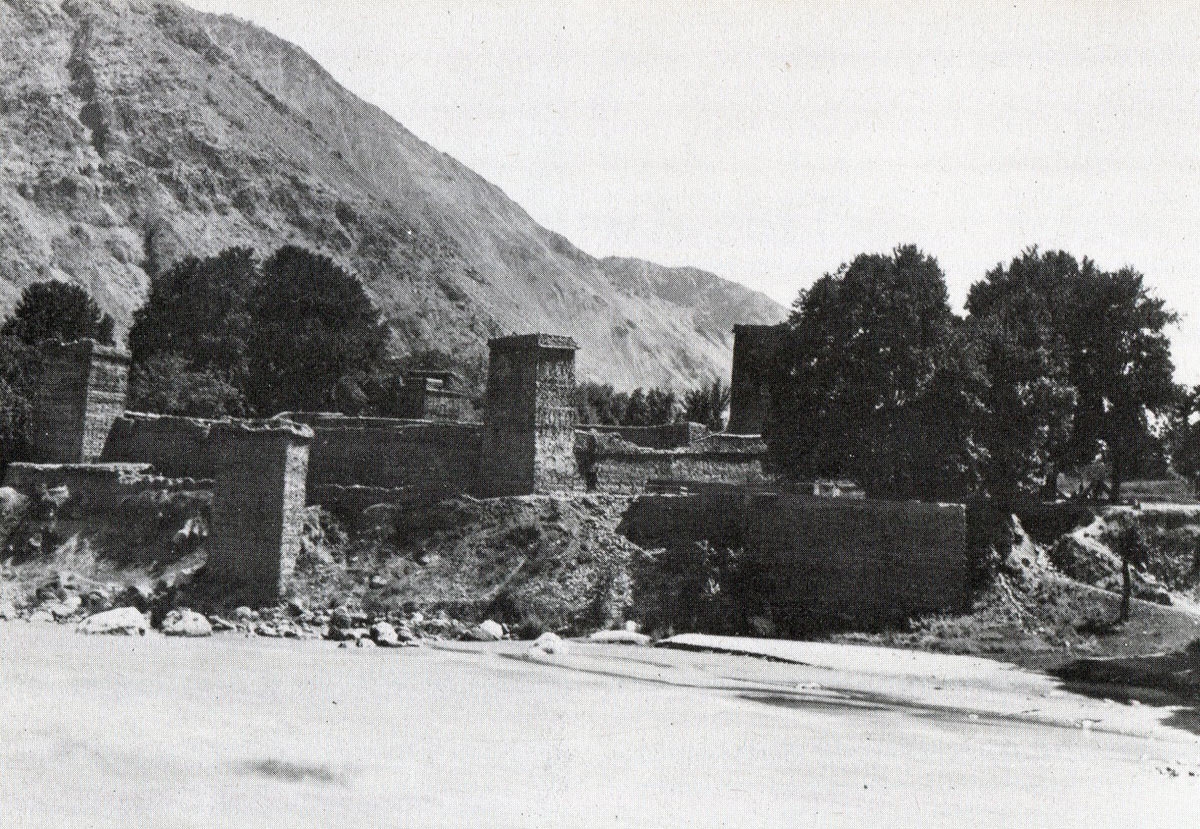

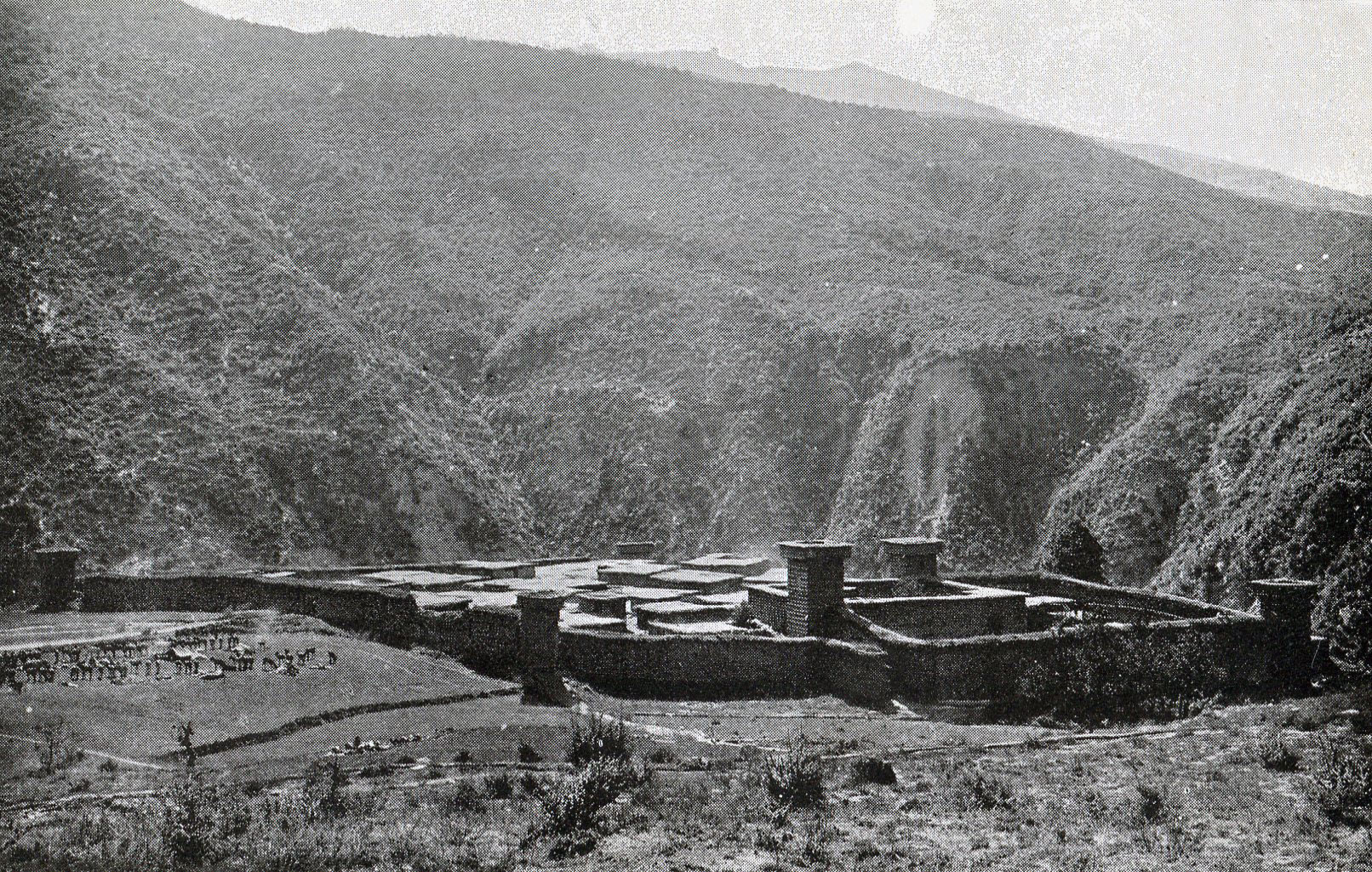

Chitral town and fort: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The centre of government was in the town, or collection of hamlets, called Chitral, on the right or west bank of the Kunar River. The principal building and residence of the Mehtar was Chitral Fort on the river bank. The Fort was the Mehtar’s treasury, storehouse and armoury, holding the resources necessary to maintain his rule.

To the east of Chitral lies Yasin, Hunza and Nagar and to the south-east lies Kashmir, all regions in 1892 subject to the rule of British India.

To the South of Chitral lay the independent tribal Pathan regions of Jandol and Dir. South of these areas lay the Kabul River with the British military region based on Peshawar.

Along the western and northern borders of Chitral lies Afghanistan.

The principal routes into Chitral and to Chitral itself in 1895 were; from the east along the Yasin River from Gilgit, Kashmir and Hunza and, from the south, over the Lowari Pass, from Dir, which led into the Kunar River valley.

Following the Second Afghan War between Britain and Afghanistan between 1878 and 1880, a boundary commission worked to establish the border between British India and Afghanistan, which, for the British, came to be called the ‘Durand Line’ after the British Commissioner, Colonel Algernon Durand.

The approach to the Malakand Pass: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The work of the commission had an unsettling effect on the independent tribes along the border of Afghanistan and British India. The tribes to the north of the Kabul River, including the Chitralis, felt that the establishment of the ‘Durand Line’, with their regions on the Indian side, was a significant step towards British takeover.

On 30th August 1892, a long period of relative stability in Chitral came to an end, with the death of Aman-ul-Mulk, the ‘Great’ Mehtar of Chitral. Unusually in Chitrali politics, the Great Mehtar appears to have died from natural causes. His death unleashed a period of extreme violence and intrigue between the most prominent of the Great Mehtar’s sons and his brother, to secure the vacant Mehtarship.

The eldest son of Aman-ul-Mulk, Nizam-ul-Mulk, was absent from Chitral at the time of his father’s death, enabling another son, Afzal-ul-Mulk, who was in Chitral, to seize the arms and treasure in Chitral Fort and proclaim himself Mehtar.

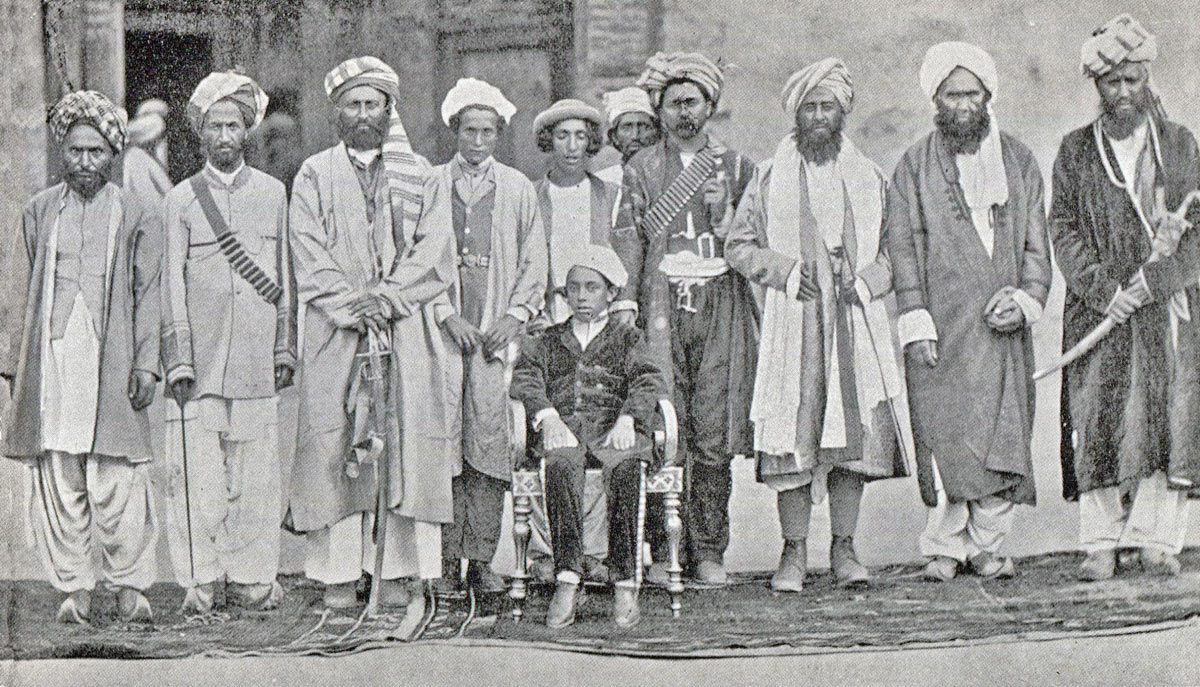

Sher Afzal and attendants: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

In November 1892, Sher Afzal, a brother of the Great Mehtar, arrived at Chitral Fort, having travelled in secret from Afghanistan, murdered Afzal-ul-Mulk and proclaimed himself Mehtar.

Sepoy of the 32nd Sikh Pioneers: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

On hearing of his brother’s death, Nizam-ul-Mulk, who had taken refuge in British territory at Gilgit, left for Chitral, with the intention of displacing Sher Afzal and taking the Mehtarship. The troops Sher Afzal sent to oppose Nizam-ul-Mulk changed sides and, in December 1892, Sher Afzal fled into nearby Afghan territory, leaving Chitral to Nizam-ul-Mulk.

At the request of the British, the Amir of Afghanistan summoned Sher Afzal to Kabul and agreed to prevent him from returning to Chitral.

Nizam-ul-Mulk requested the Indian Government to station a British officer at Chitral. Initially the British Political Officer in Gilgit, Surgeon Major Robertson, visited Chitral with a force of 50 men from the 15th Sikhs, soon to be replaced by the 14th Sikhs. In May 1893, Robertson returned to Gilgit, leaving Captain Younghusband as Political Officer in Chitral.

At this time, Nizam-ul-Mulk was having difficulty from two main sources. One was the Adamzadas (members of the Chitrali squirearchy) who remained loyal to Sher Afzal. The other cause of difficulty was Umra Khan, ruler of Jandol and Dir, to the south of Chitral, who planned to add Chitral to his expanding realm.

Following the death of the Great Mehtar, Umra Khan had seized the Chitrali Fort of Narsat on the Kunar River to the south of Chitral Town and made threatening moves further up the river.

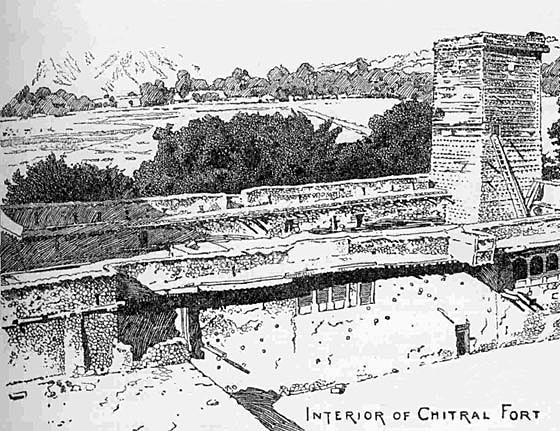

Interior of Chitral Fort: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

In September 1894, Captain Younghusband moved to Mastuj, a remote fort to the north-east of Chitral town, on the Yarkhun River and on the route to Gilgit, which became the headquarters for the British Political Officer. In October 1894, Lieutenant B.E.M. Gurdon took over the post from Younghusband.

Lieutenant BEM Gurdon: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

On 1st January 1895, the Mehtar of Chitral, Nizam-ul-Mulk, was murdered, while hunting, at the instigation of his brother, Amir-ul-Mulk. Amir-ul-Mulk seized the Chitral Fort and claimed the Mehtarship. It may be that the murder was intended at the time to further the return of Sher Afzal as Mehtar. Umar Khan was invited to invade Chitral in support of Sher Afzal. Amir-ul-Mulk changed his mind, decided to retain the Mehtarship and asked Umar Khan to withdraw. Umar Khan had in the meantime crossed the Lowari Pass into Chitral and advanced up the Kunar River to Kala Drosh, the next major fort on the road to Chitral Town. Umar Khan refused to leave Chitrali territory.

At the time of the murder of Nizam-ul-Mulk, Lieutenant Gurdon, the British Political Officer, was in Chitral Town, with an escort of 8 soldiers from the 14th Sikhs. A further 95 soldiers of the 14th Sikhs were at Mastuj Fort under Captain Ross. 286 soldiers of the 4th Kashmir Rifles were at Gupis, on the route between Mastuj and Gilgit.

Mr Udney, the British Representative on the Boundary Commission working with the Afghans and Surgeon Major Robertson, the British Agent in Gilgit, both wrote to Umra Khan, requiring him to withdraw from Chitrali territory, a demand which he ignored.

On 1st February 1895, Surgeon Major Robertson arrived in Chitral, with detachments from the 14th Sikhs and the 4th Kashmir Rifles. Robertson brought in his group another candidate for the Mehtarship, Shuja-ul-Mulk, a younger son of the Great Mehtar.

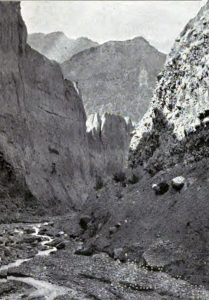

Koragh Defile: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

To the south, the Chitralis were proposing to hold Umra Khan’s advance at Drosh, a fort on the Kunar River.

On 9th February 1895, the governor of Drosh, a supporter of Sher Afzal, surrendered the fort to Umra Khan. It emerged that Sher Afzal was with Umra Khan at Drosh, despite the promise of the Amir of Afghanistan to the British to hold Sher Afzal in Kabul.

Colour Party, 14th Ludhiana Sikhs: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by AC Lovett

Correspondence took place between Sher Afzal and Robertson, in which Sher Afzal demanded that Robertson concede that he be confirmed as Mehtar and agree terms that he receive a subsidy from the Indian Government and that no European officer be permitted to enter Chitral. Robertson evaded giving any definite answer, saying that his demands had to be submitted to the Government of India.

One of the difficulties for Robertson and the other British officers during the whole Chitrali affair was that it was not easy to work out who was allying himself with whom and whether the locals who claimed to be on the same side as the British were being entirely frank.

A particular conundrum was the extent to which Umra Khan and Sher Afzal were allied. As the fighting continued and Jandol and Dir were threatened and then invaded by the British Chitral Relief Force moving up from Peshawar, Umra Khan increasingly followed his own direct interest and moved away from Sher Afzal.

During February 1895, in view of the threat from Umra Khan as he advanced north up the Kunar River, Robertson moved his force into Chitral Fort, with the members of the Mehtar’s entourage and the stores of food that Gurdon had been stockpiling since the crisis broke. Gurdon’s foresight in this respect was to be the saving of Robertson’s garrison.

Shuja-ul-Mulk, Mehtar of Chitral: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

It was apparent that the Mehtar, Amir-ul-Mulk, was communicating with Sher Afzal. Robertson placed him in custody and recognised his younger brother Shuja-ul-Mulk (nicknamed by the British troops ‘Sugar and Milk’) as Mehtar of Chitral.

On 15th February 1895, Captain Townsend, with a party of Kashmir Rifles, occupied a blockhouse on the left bank of the Kunar River at Gahirat, downstream or south from Chitral Town. Lieutenant Gurdon joined the Chitralis on the right bank.

On 18th February 1895, Gurdon took a mounted party towards the Jandoli positions at Ghosh. During this reconnaissance, Gurdon’s party was shot at and forced to retire in haste. Robertson clearly considered that Gurdon had been incautious in advancing so far and that firing on a British officer was tantamount to a declaration of hostilities. The British party fell back to Chitral Town and occupied the bridge towers over the river.

On 3rd March 1895, Sher Afzal occupied villages within two miles to the South of Chitral Town. Captain Campbell, the senior British military officer, advanced to meet Sher Afzal with 200 men of the 4th Kashmir Rifles (Dogras and Gurkhas). Lieutenant Gurdon in his ‘Memories of Chitral’ described how he attempted to dissuade Campbell and his second-in-command, Captain Baird, from attacking the Chitralis. It was clear to Gurdon that these two officers underestimated the fighting qualities of the substantial number of tribesmen who were opposing them, many of whom were armed with breach loading rifles and were skilled mountain fighters and overestimated the competence of their own soldiers from the Kashmir Rifles, who were not fully trained in the use of their firearms.

Gurdon described how members of the Kashmir Rifles dropped rounds of ammunition during the fighting on 3rd March 1895 and failed to recover them, Gurdon picking up some of them himself. Robertson commented on the Kashmir soldiers firing too high.

Bridge at Chitral: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Gurdon urged Baird not to attack without support from the unengaged party of Kashmir Rifles, particularly as the Jandolis and Chitralis had infiltrated along the heights to their rear. Baird insisted on his rash assault, which lead to his own fatal wounding and the death or incapacitation of most of his men.

Captain J. McD. Baird: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

In the fight on 3rd March 1895 the Chitralis and Jandolis inflicted heavy casualties on the Kashmiris and Captain Baird was gravely wounded in the stomach. Campbell received a severe wound to the knee. Gurdon took over command and, after putting Baird in the care of Lieutenant Whitchurch of the Indian Medical Service, conducted a difficult withdrawal through Chitral Town to the river bridge.

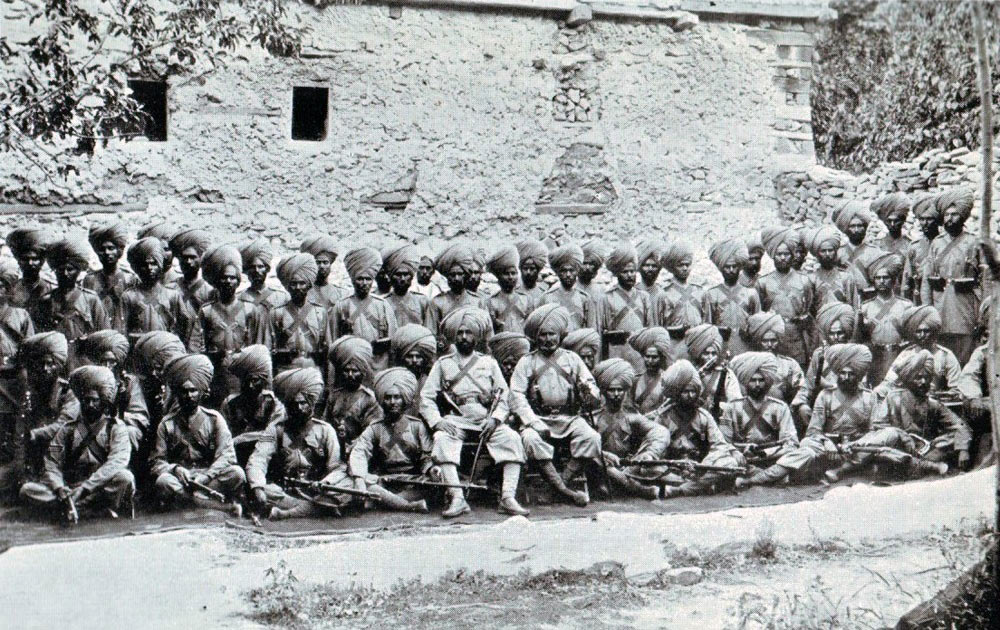

Lieutenant Harley provided cover for the final retreat to the fort with 50 of the 14th Sikhs. The Sikh and Kashmiri troops withdrew into Chitral Fort and the siege began on the evening of 3rd March 1895.

In the action on 3rd March 1895, the Kashmiris suffered 25 dead and 30 wounded, out of 150 men engaged.

Robertson’s view was that the heavy defeat of the Kashmir Rifles on 3rd March 1895 made them largely ineffective during the siege and ruled out aggressive action by the garrison, until Harley’s sortie against the mine on 17th April 1895, which was unavoidable and largely carried out by his Sikh soldiers.

Account of the Siege and Relief of Chitral:

The Siege, which lasted from 3rd March to 20th April 1895:

The elements of the Siege and Relief of Chitral are these:

- The fighting on 3rd March 1895, immediately before the siege, in which Captains Campbell and Baird were wounded.

- The Siege of Chitral Fort itself, involving Robertson and his officers.

- The loss of Captain Ross’s party in the Goragh Defile, in its attempt to march from Mastuj to Chitral.

- The capture of Lieutenants Edwardes and Fowler at Reshun, on the route between Mastuj and Chitral and the loss of their party.

- Colonel Kelly’s march from Gilgit in the east to the relief of the Fort.

- General Low’s march from the south to relieve the Fort.

Chitral Fort was invested on 4th March 1895, by the Chitrali forces of Sher Afzal and the Jandoli soldiers of Umar Khan.

Captain Baird died of his wound on 4th March 1895. Captain Campbell was too incapacitated by his knee wound to take any active part in the siege. The British officers left to Robertson were Lieutenant Gurdon, his deputy political officer, Captain Townsend who became the senior British military officer, Lieutenant Harley of the 14th Sikhs and Surgeon Captain Whitchurch. The troops were 99 men of the 14th Sikhs and 301 men of the 4th Kashmir Rifles. Robertson, in his account of the siege, states that the Kashmiris were shaken by their defeat on 3rd March 1895 and their efficiency impaired by the experience (that the besiegers were able to set fire to the Gun Tower on 6th April 1895 was attributed to the slackness of the 2 Kashmir soldiers in the tower). Whenever there was a task during the siege that required reliable troops the Sikh soldiers were used.

Umra Khan’s Jandoli soldiers: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The garrison could never know the exact make-up of the attacking forces, which changed from day to day. The main components were the Chitrali adherents of Sher Afzal and a large contingent of Umra Khan’s soldiers from Jandol and Dir, with some Afghans.

Fowler and Edwardes, when they arrived in Chitral as prisoners, saw men in the uniforms of six Indian Army regiments, who appeared to be deserters serving in Umra Khan’s force. In fact, there were probably deserters from up to eleven British Indian regiments.

An emissary from the besiegers, who came to the fort on several occasions, stated that he had left the 5th Punjab Infantry in the Indian Army, to serve as a subadar in Umra Khan’s army. This man saluted the British officers and stood to attention when speaking to them.

As Colonel Kelly’s relief column from Gilgit made its presence felt, after crossing the Shandur Pass on 7th April 1895, besiegers were drawn off to contest the column’s advance to Chitral. Equally, as the Chitral Relief Force moved northwards towards and then into Jandol and Dir, Umra Khan summoned many of his soldiers to face this threat. Umra Khan himself left Chitral early in the siege and returned to Jandoli territory.

The weapons available to the besiegers ranged from old muzzle loading, long jezails and old British Army issue Brown Bess muskets, to many Enfield rifles and a significant number of Martini-Henry rifles.

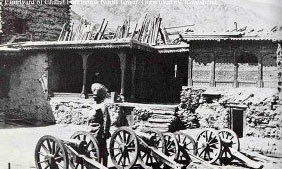

The guns in Chitral Fort: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The besiegers had no artillery. Chitral owned three 7 pounder guns, but these were in the fort. The garrison made two attempts to use these guns, but neither was successful and it was clear that they were more risk to the fort than to its besiegers, as there were no trained gunners in the garrison.

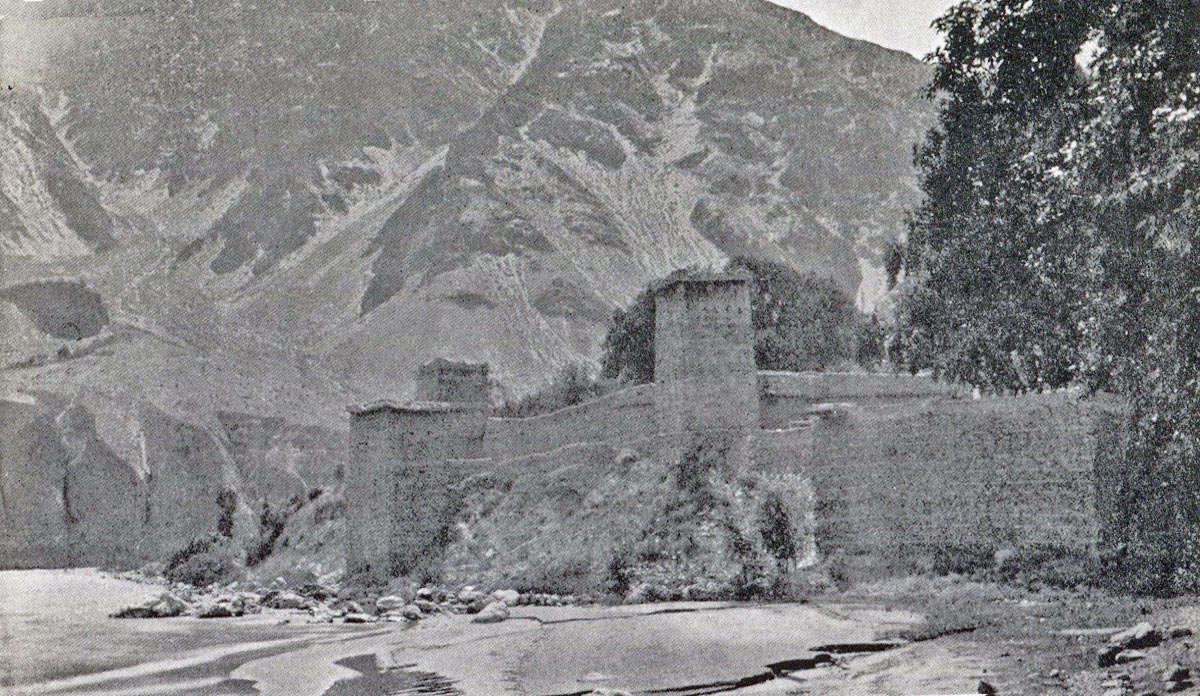

The Kunar River runs from the north-east to the south-west. Chitral Fort lay on the right or west bank of the Kunar River, at a point where the river describes a half circle and runs west to east for a short distance.

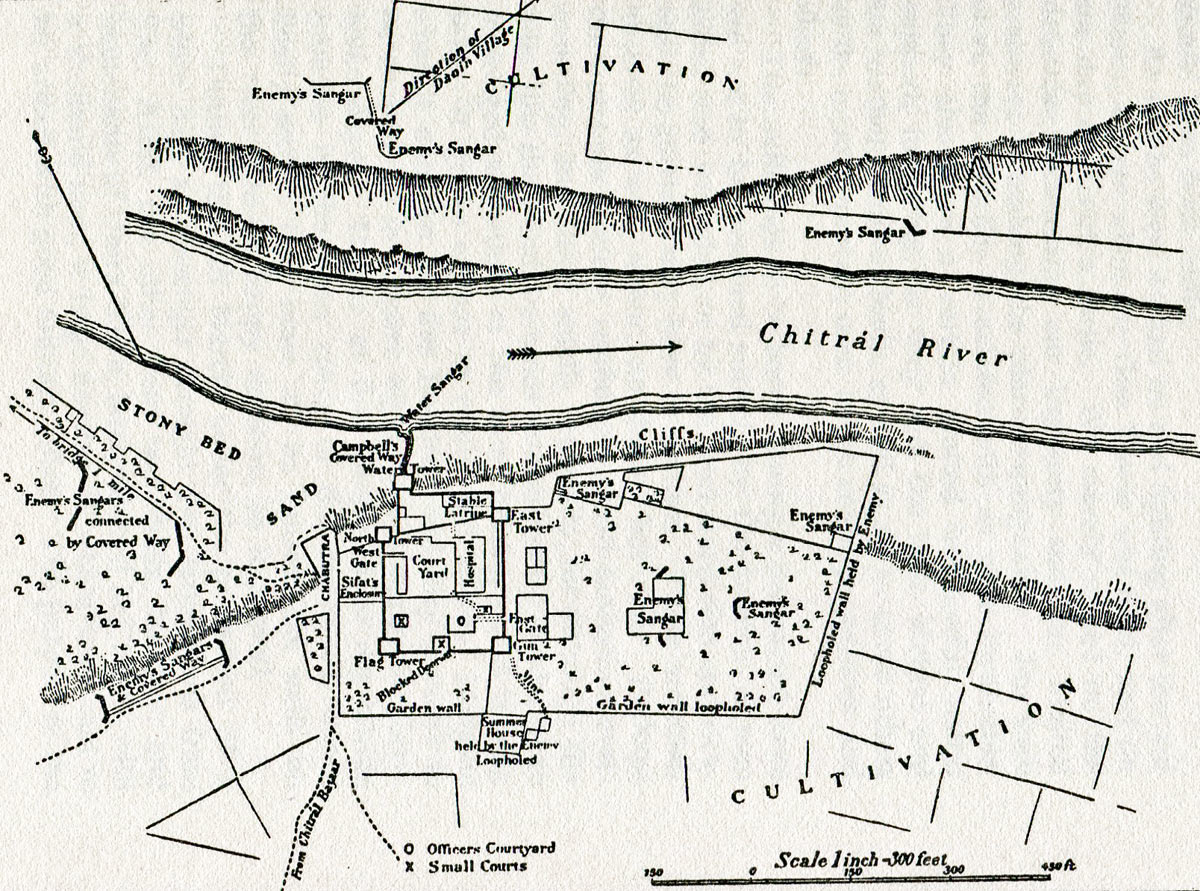

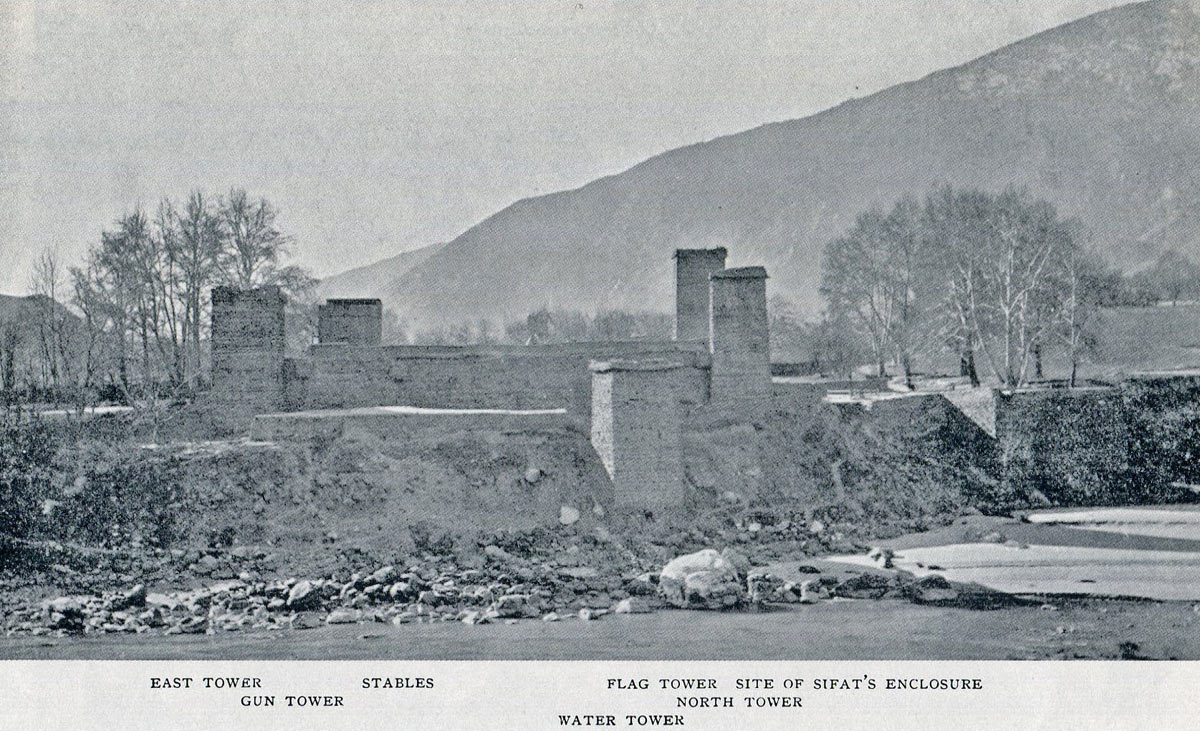

The official Indian government history describes the Chitral Fort in these terms: “The fort was of the ordinary local type, about seventy yards square. The walls, which were twenty-five feet high, and seven or eight feet thick, were constructed of rough stone, rubble, and mud, and were held together by a kind of cradle work of timbers. At each corner a square tower rose about twenty feet above the walls, and a fifth tower, known as the water tower, guarded the path to the river, which was further protected by a recently constructed covered-way (this had been built by Campbell as a precaution in case the fort had to be used to withstand a siege). Outside the north-west face was a range of stables and outhouses. The fort was practically commanded on all sides, and, except on the river front, was surrounded by houses, walls, and trees, which allowed the enemy to approach under cover close to the defences.”

Chitral Fort plan: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The towers were identified with these names: Flag Tower (at the south-west corner), North Tower (at the north-west corner), Gun Tower (at the south-east corner), East Tower (at the north-east corner) and Water Tower (by the river, nearly in line with the North Tower). The walled area of the fort was square in shape, except on the north or river side. Here, the wall followed the line of the river. The main gate was in the West Wall, next to the North Tower. The second gate, called the East Gate or Garden Gate, lay in the East Wall, next to the Gun Tower. Between the North Wall and the Kunar River was an enclosure and Stable Block. The Water Tower was at the western corner of this enclosure and Campbell’s Covered Way led from the Water Tower to the river bank (Campbell had caused the Covered Way to be built before the siege started, to ensure the garrison could remain under cover while taking water from the Kunar River).

The fort lay in a rectangular walled garden, extending to the south and the east of the fort. The garden was held by the besiegers who loop-holed the wall and sniped from it.

Various buildings lay outside the perimeter of the fort, notably the Summer House to the West of the Gun Tower. Robertson considered clearing the houses away from the fort’s walls before the siege began, but decided it was likely to alienate the Chitrali population. Many of the structures were cleared away during the siege.

The Chitralis and Jandolis built sangars or short walls of stones around the fort during the siege, some as close as 25 yards from the walls. The besiegers were particularly adept at this form of operation.

Chitral Fort; looking out over the river, North Tower on left: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Fascines of branches were used to conceal the area where a sangar was being built. Demonstrations would take place elsewhere on the perimeter to divert the garrison’s attention and the sangar erected, often overnight. The main besieger’s sangars were positioned in the garden and opposite the Main Gate and the West Wall. Sangars across the river, on the edges of the village of Danin, enabled the besiegers to maintain a near constant sniping at the members of the garrison in Campbell’s Covered Way and the Water Tower or when collecting water.

During Harley’s sortie to destroy the Gun Tower Mine on 17th April 1895, Robertson was struck by the speed with which the Jandolis built a sangar, after being surprised and driven out of the Summer House, from which they maintained an effective fire on the Sikhs and Kashmir Rifles of Harley’s party.

A continuing task for the garrison was to improve the quality of the fort’s defences. Conferences would be held during the evening, at which improvements would be devised and the work would, if possible, be carried out during the next day.

A corps of workmen was formed from the Chitralis, of whom there were 52 in the fort, headed by a Chitrali called Sifat Bahadur. They performed good service. The tasks required were to repair and improve structures, build sangars and put loopholes in the walls, particularly where there was limited vision of the areas outside the fort. Many parts of the fort were vulnerable to sniper fire and these had to be concealed.

Chitral Fort from an up-stream Chitrali sangar: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Robertson gave the distribution of the garrison on 29th March 1895 as: 10 soldiers at the main West Gate, 6 soldiers at the Garden Gate, 16 soldiers for each of the four fort towers, 10 soldiers for each of the four parapets, 10 soldiers watching Chitralis considered to be unreliable, 20 soldiers in the picket on Campbell’s Covered Way, 25 soldiers in the Water Tower, 25 soldiers in the stables, 10 Sikhs in the doorway leading to the stables, 6 soldiers guarding the Kashmir Rifles Snider ammunition (the Sikh Martini-Henry ammunition was held at the Main Gate). This left 167 soldiers uncommitted at any one time.

Discipline was maintained as far as possible, with bugle calls blown as regularly as in cantonment. The besiegers blew a bugle in reply at first, but then gave up. It seemed to Robertson that the besiegers’ bugler was probably sent up the valley. The bugler returned later and resumed his playing.

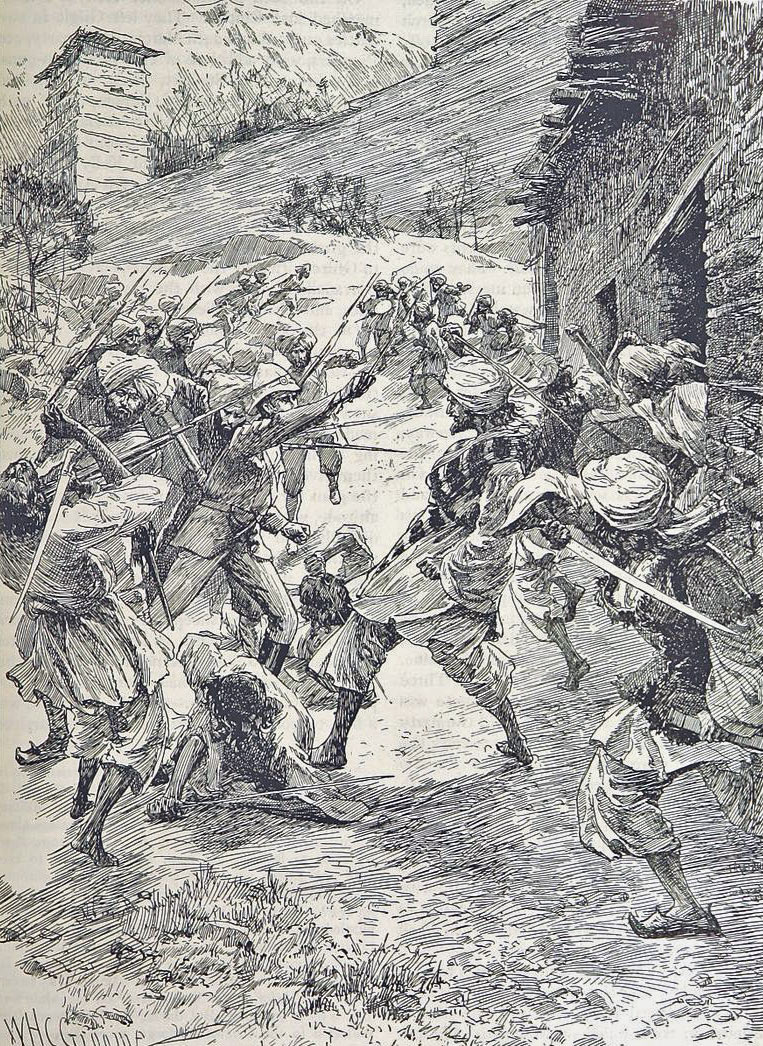

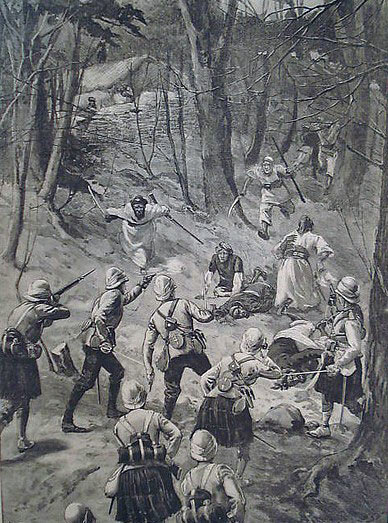

Lieutenant Harley’s Sikhs storming the Chitrali tunnel: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The garrison was subject to frequent rifle fire from the surrounding forces, who built sangars near the walls, some as close as 25 yards and from sangars across the river. While much of the rifle fire was random there was also highly accurate sniping, particularly across the river on the Water Tower and Campbell’s Covered Way, the passage that was used to bring water from the river.

On 9th April 1895, the day Colonel Kelly reached Mastuj Fort and the Chitral Relief Force moved into the Panjkora River Valley, the besiegers began a bombardment of the fort, using slings to throw stones. This was surprisingly galling and inflicted some severe injuries on members of the garrison.

Falling stones made movement across the fort yards dangerous. The rattling of stones on the fort’s fabric kept the garrison awake and on edge and clearing up the stones took considerable effort each morning.

The garrison was constantly prepared for a massed attack by the besiegers. Robertson, in the light of information received after the siege, concluded that Umra Khan was so put out by the scale of casualties inflicted on his troops by Edwardes and Fowler’s party in the fighting at Reshun and by Ross’s Sikhs that he vetoed any direct attack on the fort.

Chitral Fort from across the river: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

It was Robertson’s conclusion that the besiegers were confident of starving the garrison into surrender and that they did not realise that the garrison had substantial supplies, albeit that they were on reduced rations, which were about to be reduced to half rations when the siege ended. During the extensive contacts between besieged and besiegers, Robertson required that demands always be made for food, to give the impression that the garrison had less than in fact it had.

Lieutenant HK Harley: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

A problem with the stocks of grain in the fort was that the only grinding facility available to the garrison was a grinder manufactured by a Sikh soldier. The grinder used soft stone, because it was all that was available, with the result that fragments of grit became mixed with the flour, causing intestinal illness for the soldiers. There was some rum and tea. The officers had some tobacco. There appeared to be sufficient ghi to cook the soldiers’ food. Ponies were eaten by the British officers.

Beynon in his book ‘With Kelly to Chitral’ gives this description of the Kashmir Rifles after the siege:

‘The next day the Kashmir troops of the garrison came out and camped with us, and revelled in the fresh air after the poisonous atmosphere of the fort. Poor chaps! they were walking skeletons, bloodless, and as quiet as the ghosts they resembled, most of them reduced to jerseys and garments of any description, but still plucky and of good heart. They cheered up wonderfully in a few days with good fresh air and sleep, and marched from Chitral quite briskly when they left.’

Supplies of ammunition at the beginning of the siege were 300 rounds per rifle for the Martini-Henrys of the 14th Sikhs and 280 rounds per man for the Sniders of the 4th Kashmir Rifles. This was considered sufficient but not generous. From 12th March 1895 Robertson asked Townsend to ensure that 30 rounds a day were fired at the house which had been Robertson’s and was now occupied by Sher Afzul.

Chitral Fort from across the Kunar River: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Relations between the members of the garrison were complex. While some of the Chitralis were considered by Robertson to be reliable, the majority were suspect. They were deprived of their weapons, confined to a particular area of the fort and guarded. It was clear that these Chitralis were in receipt of information from outside the fort. The problem was finding out what the information was and interpreting it. Robertson’s adviser and confidant among the Chitralis was Wafader Khan.

Chitralis held in Chitral Fort during the siege; Shuja-ul-Mulk, Mehtar of Chitral, sits in front: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The state of affairs outside the fort was frequently judged by the manner of the Chitralis, who did not readily pass information to the British officers. A soldier who was particularly adept at picking up information was Captain Campbell’s orderly, a smart sowar of the 15th Bengal Lancers. The orderly was severely wounded and disabled during the firing around the Gun Tower on 6th April 1895, in which he played a prominent and meritorious role. Some of Robertson intelligence came from Campbell’s sick room, originating with this orderly.

It was a curious feature of the siege that rumours would go around the garrison as to the intentions of the besiegers or the progress of the relief columns and turn out either to be right or to contain a strong hint of what was happening or was about to happen, with no indication of the origins of the information.

On occasions, the conduct of the besiegers inadvertently provided Robertson with important information about the state of the relief. For example, the besiegers fired a loud charge of gunpowder on 5th April 1895. Campbell’s orderly told Campbell he considered this to be a clear indication that a relief column was in action and using mountain artillery (this was two days after the Chitral Relief Force had attacked and forced the Malakand Pass, using artillery fire). When a visiting emissary from Sher Afzul informed Robertson that there was no relief column coming, Robertson took that as a clear indication that there was indeed a relief column nearing Chitral.

Robertson regretted that the garrison did not have a flag to fly over the fort. Harley seemed to have among his 14th Sikhs, men with every conceivable skill. One of them, a skilled tailor, was given the task of preparing a large Union Jack, from pieces of cloth found in the fort. The flag was completed on 28th March 1895. The Sikh added a number of additional devices in the centre of the flag, which, to his disappointment, he was required to remove. The Union Jack was then fastened to a long pole and secured overnight at the top of the tower at the south-west of the fort.

Robertson considered the Union Flag on the Flag Tower to be a considerable boost to the garrison’s morale and a fine gesture of defiance to the besiegers.

Soldiers of the 14th Sikhs in the Chitral garrison: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

On 6th April 1895, as the relief columns neared Chitral, Colonel Kelly from the north-east and General Low from the south, the besiegers made a desperate attempt to set fire to the Gun Tower. Robertson’s view was that this was only possible due to the inattention of the two soldiers of the Kashmir Rifles on duty in the tower. The night was spent by the garrison desperately contriving ways of pouring water on the flames in the wooden framework at the base of the tower, under a heavy rifle fire from the besiegers’ sangars. There were several casualties, including Robertson himself who was shot in the shoulder. At around 9.30am the next morning, Townsend was able to report to Robertson that the fire was nearly extinguished.

A second attempt to set fire to the Gun Tower was made the following day, 7th April 1895. The fire was spotted by Subadar Badri Singh of the 4th Kashmir Rifles and Sepoy Awi Singh of the 14th Sikhs, who extinguished it. Robertson was mystified how the besiegers could approach sufficiently close to the fort to set it on fire, only a day after the first major conflagration. The conclusion he came to was that the besiegers noted the time for changing sentries and made their move during the changeover. From then on sentries were changed at random times.

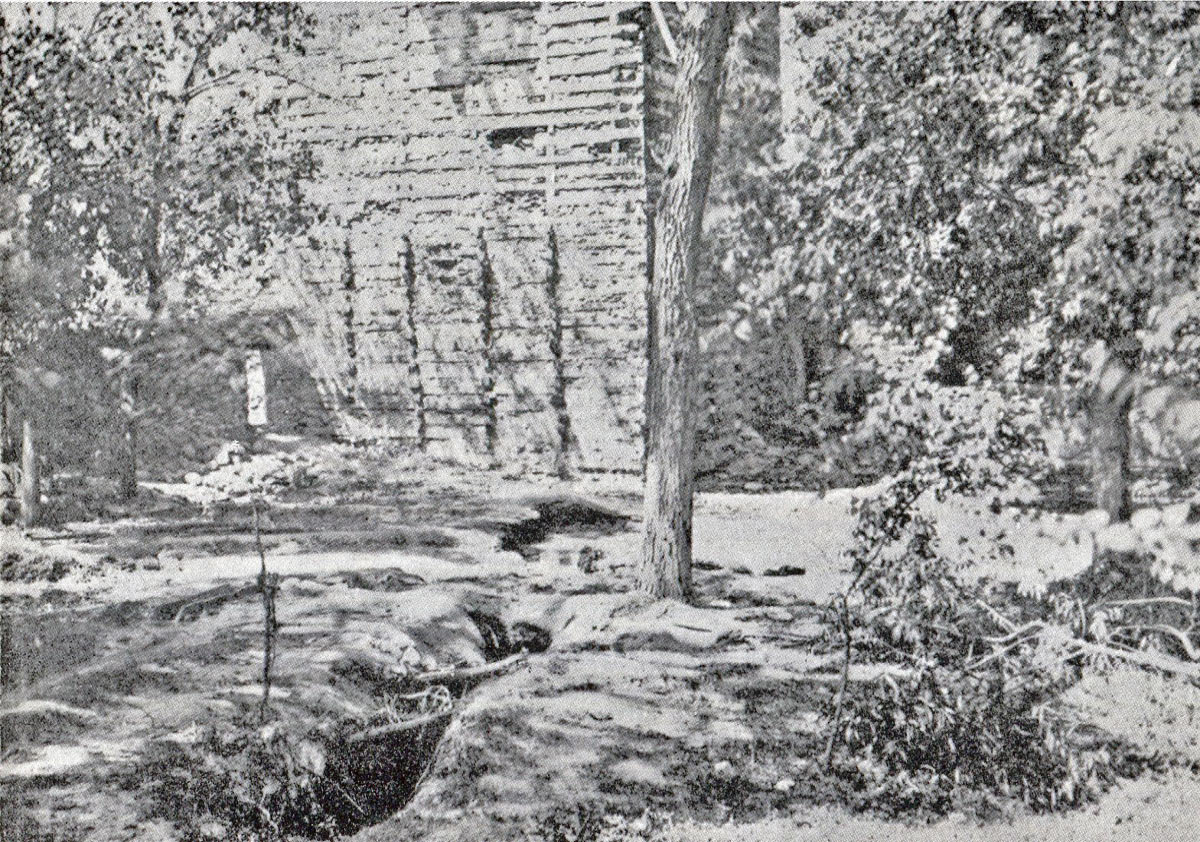

Chitral Fort; the Gun Tower and exploded mine: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The Tunnel:

In mid-April 1895, the besiegers began loudly drumming and blowing musical instruments in the Summer House, continuing hour after hour, much to the discomfort of the garrison positioned on that side of the fort.

A native cavalry officer in the garrison, Rab Nawaz Khan, reported to one of the British officers that the music was almost certainly designed to mask the sound of tunnelling.

He reported that where there was difficulty storming or otherwise capturing a fort in the region, attackers would often resort to tunnelling under the defences and exploding a charge of gunpowder to destroy them.

It seemed likely to Rab Nawaz Khan that a tunnel was being dug from the Summer House, under cover of the continuous drumming and music, with the target being the Gun Tower.

The sentries in the Gun Tower were ordered to listen carefully for the sound of picks being used under the ground between the Gun Tower and the Summer House.

Initially, while the native sentries were able to hear the faint sound of picks the British officers could not, through the loud drumming and whistling music from the Summer House, so no additional action was taken.

On 17th April 1895, the sound became so distinct that the British officers were able to hear it.

The loudness of the picks showed that the tunnel was close to the Gun Tower and there was little time to take suitable counter-measures.

Explosives in the besiegers’ tunnel might be detonated at any time, bringing down the Gun Tunnel, leaving a substantial hole in the defences.

In particular there was insufficient time for the garrison to dig a counter-mine.

A sortie to capture and destroy the mine tunnel, clearly originating in the Summer House, was organised with great speed and launched at 4pm the same day.

Lieutenant Harley led a force of 40 Sikhs and 60 Kashmir Rifles in a bayonet charge out of the Garden Gate to capture the Summer House. The besiegers were taken by surprise and withdrew to cover, from where they built a sangar and opened an effective fire.

Harley’s party bayoneted the Chitralis emerging from the mine tunnel, killing some 35 men. Two bags of gunpowder were taken into the tunnel and a fuse lit.

Harley’s men raced back to the Garden Gate. In the minutes following the sortie it was feared that the explosion had been ineffective. There was then a rumble and a long trench appeared between the Summer House and a point just short of the Gun Tower. The tunnel had collapsed, killing two more Chitralis.

The activities of the besiegers effectively ended with the destruction of the tunnel.

Attacking the mine: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by William Henry Groome

Other than these two incidents, the besiegers’ efforts comprised repeated demands for the garrison to withdraw from Chitral, rifle fire, including highly accurate sniping, the building of sangars ever nearer to the fort, slinging stones and shouting insults.

The shouting of insults became such a feature of the besiegers’ tactics that a Kashmiri soldier was given the task of shouting replies from one of the towers. He was not a competent soldier but he was extremely good at devising and shouting insults.

The exploded mine by the Gun Tower: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

On 18th April 1895, a man crept up to the fort wall and called out that the besiegers had gone. This message was treated with suspicion. On 19th April Gurdon cautiously led a party of men out of the fort and into the bazaar. It was true. The besiegers had left. Robertson immediately despatched a messenger to give the news of the lifting of the siege to Kelly. Kelly‘s column marched into Chitral on 20th April 1895.

Mastuj Fort, Reshun and the Koragh Defile:

Once Robertson marched to Chitral from Mastuj Fort, before the Siege began, Lieutenant Moberly assumed command of the Mastuj garrison of 4th Kashmir Rifles. Additional officers and troops were on their way to Mastuj from Gilgit: Lieutenant Fowler, Royal Engineers, with 20 Bengal Sappers and Miners, Captain C.R. Ross with his company of 14th Sikhs, Gilgit district levies and Lieutenant Edwardes of 2nd Bombay Grenadiers who would command the levies. Ross became the senior officer in Mastuj Fort.

At the end of February 1895, Moberly received a letter from Captain Baird at Chitral, directing him to send to Chitral 60 boxes of Snider ammunition with an escort. The column, with the ammunition, comprising soldiers from the 4th Kashmir Rifles, commanded by a Gurkha Subadar, Gurm Singh, set off, but halted on the road, as the word was that the precarious cliff pathway had collapsed.

Gordon Highlanders advancing to the Swat River: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

On 3rd March 1895, Edwardes and Fowler arrived at Mastuj Fort and went on to join the ammunition column, to take it to Chitral. The column began its march down the valley on 5th March 1895, the road following the left bank. On 6th March, Moberly received a letter from Edwardes sent from the village of Koragh, saying that he had received information that there was a gathering of hostile tribesman at Reshun, intent on preventing the column from proceeding further. Ross decided to take his company of Sikhs and support Edwardes’ column in marching on to Chitral.

It was Moberly’s emphatic advice, which he put in writing, that Ross should recall Edwardes’ and Fowler’s ammunition column and occupy the Nisa Gol ravine, which was near to Mastuj, pending the arrival of reinforcements from Gilgit. Ross ignored this advice and left for Chitral on 6th March 1985 with Lieutenant Jones and his company of the 14th Sikhs.

Later that day, Moberly received information from Ross, that he had heard that Edwardes was surrounded at Reshun. Ross had left a detachment of 40 Sikhs at Buni and pressed on with the rest of his company to reach Edwardes.

Captain Ross with 14th Sikhs: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

On 10th March 1895, Captain Bretherton arrived at Mastuj with 100 sepoys of the 4th and 6th Kashmir Regiments from Ghizr. This left Moberly free to follow up Edwardes and Ross and see what the position was. Delayed by the destruction of the bridge at Sanogher, Moberly reached Buni on 17th March 1895, where he found a wounded Jones with 14 survivors of Ross’s party and the detachment left behind by Ross at Buni.

From Jones, Moberly discovered what had happened to Ross. When the company marched out of Buni on 7th March, leaving the party of 40 sepoys, Ross was accompanied by the village headman, who warned that they would meet strong resistance. Ross clearly did not believe the headman.

At midday on 7th March 1895, Ross’s party came to the village of Koragh and found it deserted. The village headman again warned of resistance ahead, but Ross again chose to disbelieve him. Beyond the village, Ross’s party entered the Koragh Defile, where the river flows between high cliffs. At the entrance to the defile, they found that sangars had been built but were not occupied. There were tribesmen on the hillside.

Amir-al-Mulk, deposed Mehtar of Chitral, guarded by Sikh and Kashmir soldiers of the Chitral garrison: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

At the far end of the gorge, the path climbed up the cliff face. At this point, Ross’s men were fired on from up the road and large numbers of men appeared above them, rolling stones down the hillside. The opposition was said to have been villagers from Reshun and not well armed, but there was a substantial number of them. Presumably, the main armed body was busy fighting with Edwardes’ party in the village.

Ross took his men back down the path. Jones was sent with 10 Sikhs to secure the entry to the defile, but found that the sangars were now occupied and, in the ensuing fire fight, all but 2 of Jones’ men were hit. Jones re-joined Ross and the party took cover in caves at the bottom of the cliff, where they were sniped at by Chitralis across the river.

That night, another attempt was made to force the road up to the top of the cliff, but failed. After a further day of sniping, Ross’s party attempted to climb the cliff immediately above them. A sepoy fell from the cliff and the climb was abandoned. Later that night, Ross led his men back down the path towards Buni. Ross was shot after clearing a sangar of Chitralis and killed. Jones escaped out of the defile with 17 Sikhs. Once in more open country, they were able to drive off their attackers with volley firing. The survivors, Jones with14 of the original 60 Sikh soldiers, all but a couple now wounded, returned to Buni where Moberly found them.

Mastuj Fort: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Moberly’s party returned to Mastuj Fort, which they reached with some difficulty, being under attack for much of the route.

A group of the Sikhs did not follow Ross in his retreat back down the track to Buni. These men took shelter in the caves and after a week and a half with no food surrendered to a number of Chitrali chiefs, against undertakings that their lives would be spared. In fact, all but one of the Sikhs were hacked to death by the Chitralis the day after their surrender. One Sikh was spared so that he could be killed by another headman who was not present. He relented and the Sikh survived.

The British officers prepared to be besieged in Mastuj Fort. Although they were blockaded and sangars were built around the fort, there was no real siege and the garrison suffered no casualties.

On 9t April 1895, a sentry in Mastuj reported that he could hear cannon fire. The British officers were unable to hear any firing. Muhammed Isa’s men were driven from the Chakalwat position by the Gilgit Relief Column past Mastuj Fort before anything could be done to intercept them.

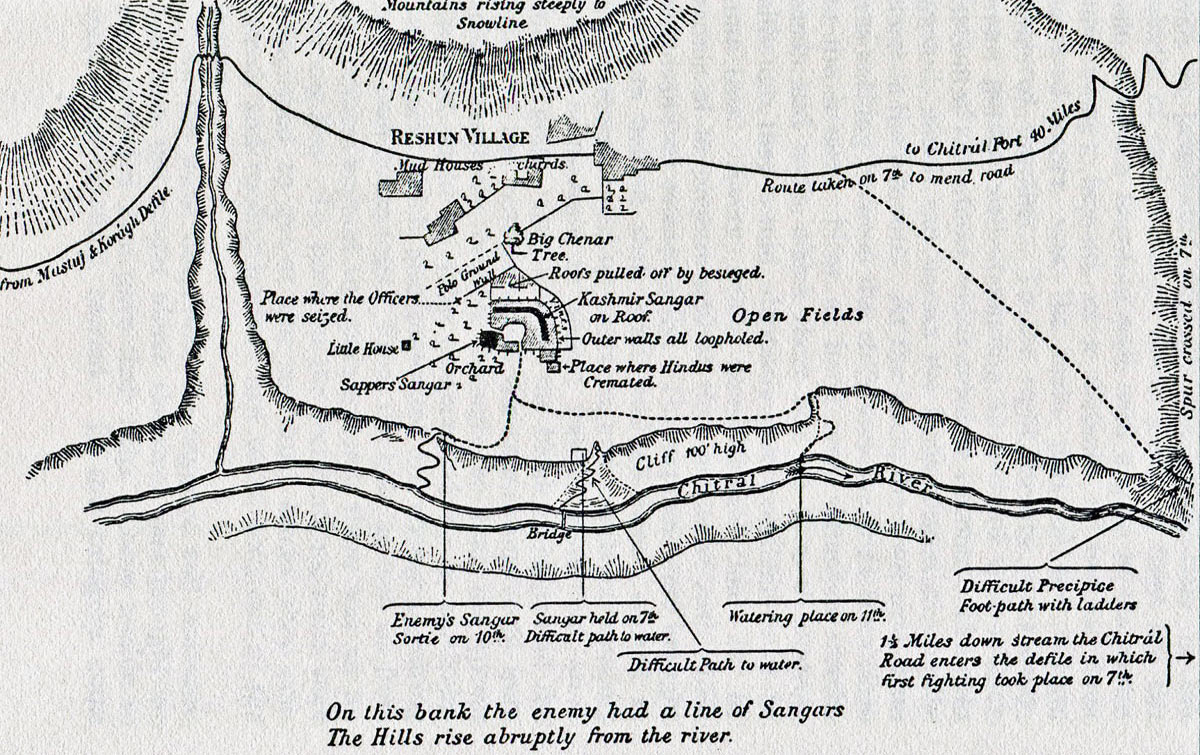

Edwardes’ and Fowler’s column:

On 6th March 1895 Edwardes and Fowler’s ammunition column, comprising some 150 porters carrying the supplies and baggage, escorted by Dhurm Singh and his 40 riflemen and Fowler’s 20 Bengal Sappers and Miners, continued on their route to Chitral.

After leaving Koragh village, Edwardes and Fowler were informed that Robertson’s force was under siege in Chitral Fort. They decided to press on to Reshun village and halt there.

Plan of Reshun, which lies south of the river: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

At Reshun, Edwardes and Fowler were informed that the attack on the fort involved Chitralis as well as Umra Khan’s troops. This put their position in the heart of Chitrali country in a different light. Until then, they had believed that they were on the same side as the Chitralis.

The Yarkun River at Reshun runs through a deep gorge with precipitous cliffs on each side, rising to 100 feet. Edwardes’ and Fowler chose to camp on the edge of the cliff, rather than on the polo ground offered to them by the village headmen, where they would be surrounded.

The next day, 7th March, Dhurm Singh was left with 30 Kashmir troops in the encampment to guard the ammunition and to build a sangar. Edwardes’ and Fowler took the rest of the troops in a reconnaissance along the road. Near a village called Parpish, Fowler took a small group up the mountain side in pursuit of a lone armed man. Men came out from Parpish and opened fire across the river at both officers’ parties. They were forced to make a hurried retreat to the camp at Reshun, which they reached with considerable difficulty, more attackers appearing from Reshun itself.

Biddy, Lieutenant Edwardes’ fox terrier injured in the fighting at Reshun: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Edwardes and Fowler now decided that the troops must capture a group of buildings nearer the village, to have a reasonably defensible camp. Fowler led Dhurm Singh and 20 of his men in a bayonet charge which took the main buildings. The rest of the column, with the wounded and the stores, were moved up from the camp. Among the wounded was Edwardes’ fox terrier, Biddy, which had been shot through the chest.

On 8th March 1895, the gathering Chitralis kept Edwardes’ and Fowler’s party under continuous fire, which achieved little. Once night had fallen, the two officers took a party down to the river and came back with a substantial supply of water. This hazardous expedition seems not to have been noticed by the Chitralis.

The fighting continued on 9th and 10th March 1895. Soldiers claimed they could hear distant firing. This is likely to have been Ross’s Sikhs being engaged in the Koragh Defile.

On the night of 10th March 1895, Fowler led a sortie against the main Chitrali sangar, with considerable success. On 11th March, another sortie to collect water from the river was carried out and on 12th March there was a heavy rainfall. The problem for the column was their dwindling food stocks.

On 13th March 1895, there were negotiations between the Chitralis and the two British officers, who were informed that Muhammed Isa, Sher Afzul’s foster brother, had arrived from Chitral with a large force.

On 15th March 1895, Edwardes’ and Fowler were persuaded to join Muhammed Isa in watching a polo match on the ground immediately next to the buildings held by their troops. During the course of the match, Edwardes’ and Fowler were overpowered and the buildings immediately stormed, with most of the Kashmiri troops and the Sappers and Miners killed, other than a small group of Muslim soldiers who were taken prisoner. Dhurm Singh and his men put up a ferocious resistance until they were overwhelmed.

Fowler and Edwardes, with Biddy after their capture: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

After considerable argument as to what to do with the two British officers, they were taken to Chitral and finally handed to the Chitral Relief Force. Edwardes’ fox terrier, Biddy, accompanied him.

It seems clear that Edwardes’ and Fowler’s troops inflicted considerable casualties on the Chitralis and Jandolis besieging them in the buildings at Reshun. It was Robertson’s understanding that Umra Khan was so put out at the number of his soldiers killed at Reshun, that he directed that there was to be no attempt to storm Chitral Fort for fear of casualties on a similar scale.

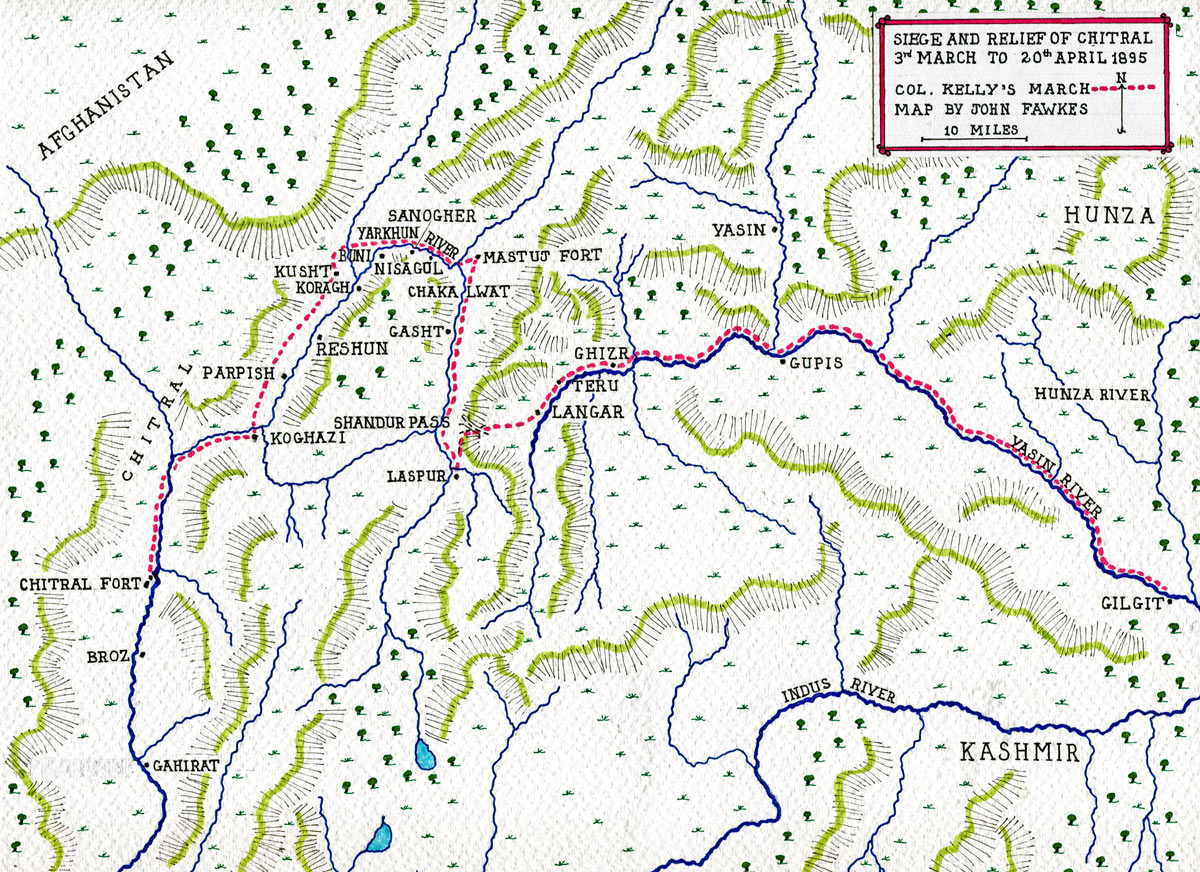

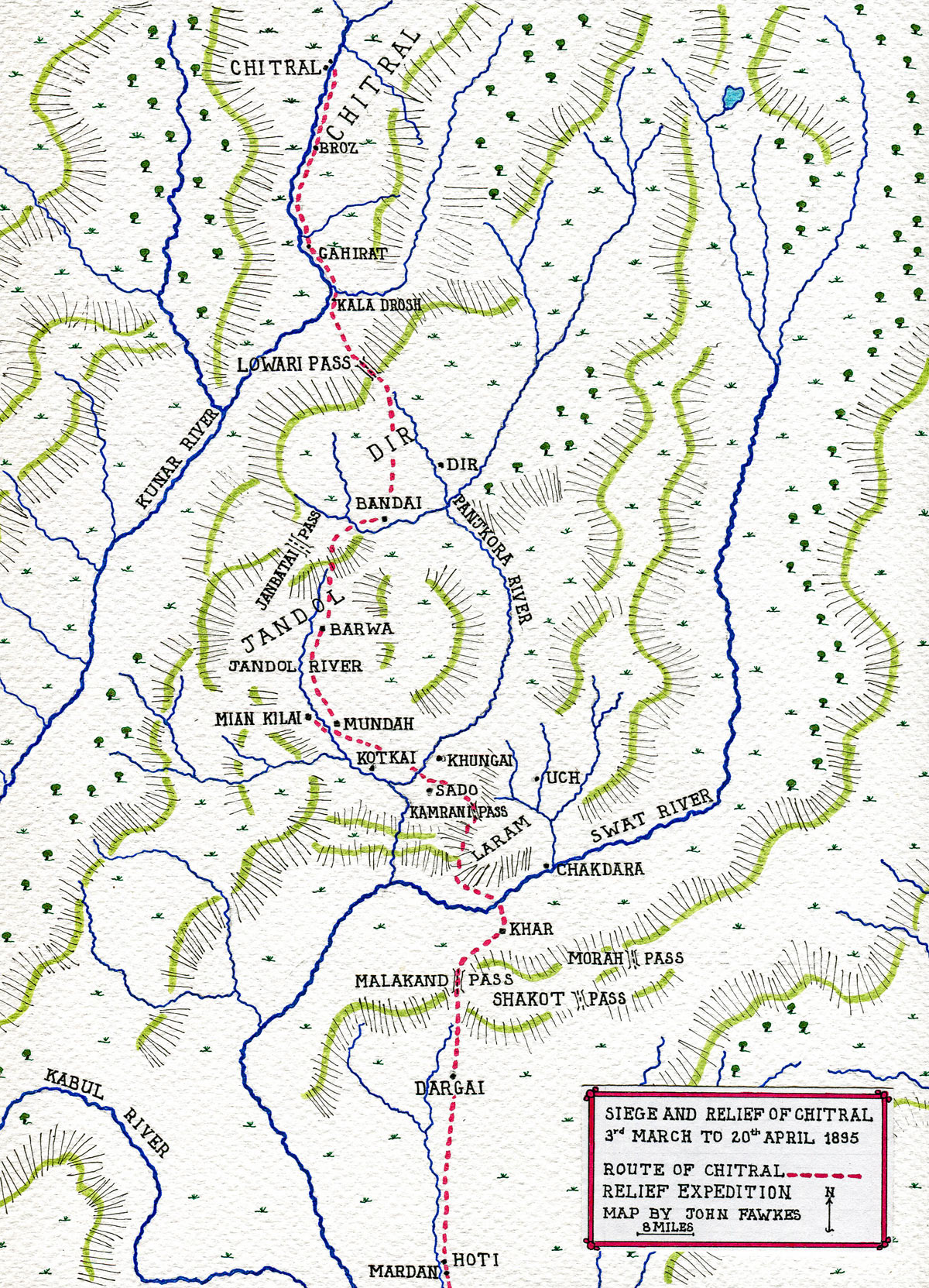

Map of Colonel Kelly’s march from Gilgit to Chitral: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India: map by John Fawkes

Colonel Kelly’s relief column from Gilgit:

The Indian Army regiment, the 32nd Punjab Pioneers (Sikh soldiers), was in the district of Gilgit, building a road during the winter of 1894/5.

Lieutenant Colonel Kelly, 32nd Sikh Pioneers: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

In early March 1895, the Assistant British Agent in Gilgit, Captain W.H. Stewart, Royal Artillery, asked Lieutenant Colonel Kelly, commandant of the 32nd Pioneers, to bring half his regiment to Gilgit, in view of the news from Surgeon Major Robertson in Chitral, that his force was facing hostile action by Umra Khan.

The half battalion reached Gilgit on 22nd March 1895. On the same day, Colonel Kelly received instructions to take command of all British and Indian troops in the Gilgit Agency and take what steps he considered necessary. Kelly was informed that a force comprising three brigades was due to advance on Chitral from the Peshawar area via Swat. The Government in India did not consider that it was feasible to mount a relief of the Chitral garrison from Gilgit, as the route was considered impassable in winter.

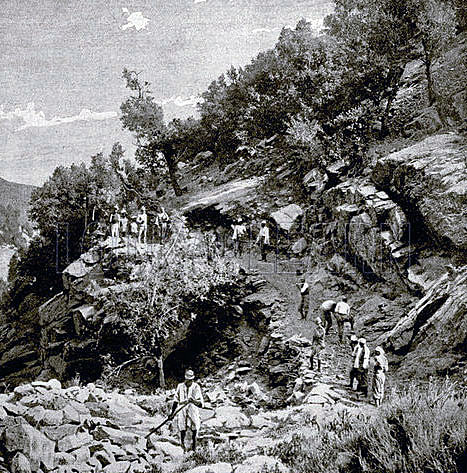

Cliff path on Kelly’s route to Gupis: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The information available to Kelly was that Robertson’s force was under siege in Chitral Fort by Sher Afzal and Umra Khan, that Lieutenant Moberly held the fort at Mastuj and that Fowler and Edwardes had left to provide further ammunition and supplies to Robertson in Chitral. It was known that Captain Ross had been killed and his party repelled in the Koragh gorge.

Colonel Kelly decided to lead a column along the Yasin River from Gilgit, to relieve Mastuj and Chitral forts. Kelly’s staff officer was Lieutenant W. Beynon of the 3rd Gurkhas. The forces available to Kelly were scattered across Gilgit and Hunza and comprised the 4 guns of Number 1 Battery Kashmir Mountain Artillery, his own regiment of some 800 men, around 200 Sappers and Miners and some 800 soldiers of two regiments of Kashmir Imperial Service troops, the 4th Kashmir Rifles, a strong detachment of which was with Robertson in Chitral, and the 6th Kashmir Light Infantry.

With these forces, Kelly had to maintain security in the areas of Hunza, Nagar and Chilasi, in addition to manning the relief column for Chitral and Mastuj. The troops committed to the column were 400 soldiers from the 32nd Sikh Pioneers and a 2 gun section of No1 Kashmir Mountain Battery. The chiefs of Hunza and Nagar provided some 1,000 levies, who were used as porters for supplies and as garrisons along the route to Mastuj.

Pioneers of the Indian Army: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by AC Lovett

Kelly’s route from Gilgit to Mastuj lay westwards, along the valley of the Yasin River and was around 140 miles. Beyond Mastuj, the route to Chitral lay along the valley of the Yarkun River for about 60 miles, before it joined the Kunar River some five miles above Chitral Fort. Before reaching Mastuj, Kelly’s force would have to cross the Shandur Pass.

Colonel Kelly with the officers of the 32nd Sikh Pioneers: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

There was a road for about fifty miles from Gilgit to Gupis, where it left the Yasin River valley and turned north to Yasin. Thereafter, the route along the river valley was by track. The Shandur Pass was likely to be snow bound. The local population beyond the pass could be expected to be hostile to British forces and to put up resistance in sympathy with the Chitralis. The weather would be snowy, with blindingly fierce sunshine during the day, coupled with freezing temperatures at night. Troops were permitted to carry only 15 pounds of baggage and no tents were taken.

The column marched in two detachments, on 23rd and 24th March 1895 and arrived in Ghizr Fort on 30th and 31st. Some 150 men were taken on from the small garrison at that fort.

Shandur Pass: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The whole column marched on 1st April 1895 for the next village of Langar, the final place of refuge before the long crossing of the Shandur Pass and some twelve miles from Ghizr. There was now five days of snowfall along the route, which was so deep as to be nearly impassable. The column was forced to halt at the village of Teru, well short of Langar.

Kelly returned to Ghizr, leaving a force under Captain Borradaile at Teru to attempt the crossing of the Shandur Pass.

On 2nd April 1895, the guns were brought up to Teru and Borradaile’s detachment began the struggle to cross the pass. The mules carrying the guns were quickly brought to a halt by the deep snow. An attempt was made to clear a path by taking a herd of native yaks up the track.

Sikhs carrying the mountain guns across the Shandur Pass: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by William Overend

This produced no improvement as each animal carefully trod in the hoof prints of the preceding yak and failed to produce a flattened path as hoped. Captain Stewart, the mountain battery section commander, took his men into the river, in an attempt to find secure footing, but the result was severe freezing for the men and animals. The gun mules were left in a village and the guns and equipment carried and dragged on makeshift sledges, the gunners assisted by the other soldiers. Eventually, the guns and equipment were left in the snow, in marked positions and Borradaile’s detachment marched on, reaching Langar at 11pm. The troops returned the next day and brought the guns into Langar. The mules went back to Ghizr.

Borradaile’s men were now 12,000 feet above sea level, in freezing conditions and deep snow. Langar contained only one hut, in which the worst affected soldiers were lodged, the remainder bivouacking in the snow.

Colonel Kelly with his staff (from left: Lt Stewart RA, Lt Peterson, Lt Beynon, Lt Cobbe, Surg-Capt Luard, Lt Jones, Col Kelly, Lt Bethune, Surg-Capt Browning Smith, Captain Borrodaile, Lt Moberly, Sgt Reeves): Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Borradaile marched on 3rd April 1895 to cross the Shandur Pass, leaving the gun section and an escort of the 4th Kashmir Rifles at Langar. The distance across the pass was about ten miles and in the summer is not considered difficult. The pass was filled with snow, up to five feet deep, causing the column to travel at less than a mile an hour, the soldiers being encumbered with weapons, ammunition and supplies.

Borradaile’s detachment reached the village of Laspur, at the far end of the pass, at around 7pm. Resistance was anticipated, but the villagers had no expectation that the British/Indian column could get across the pass in such conditions and were taken by surprise.

Band of the 32nd Sikh Pioneers: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

On 4th April 1895, Borradaile fortified part of the village and sent porters back to assist in bringing Stewart’s gun detachment and the escort of Kashmiris commanded by Lieutenant Gough on from Langar. Stewart’s detachment arrived in the evening, after an exacting journey in which the heavy guns had to be carried through the snow by the soldiers. Many of Stewart’s soldiers were inflicted by snow blindness. There were a few pairs of snow goggles with darkened lenses. These goggles were given to a small group of gunners, who were ordered to keep them on at all times, so that there would be sufficient men who could see fully to fire the guns.

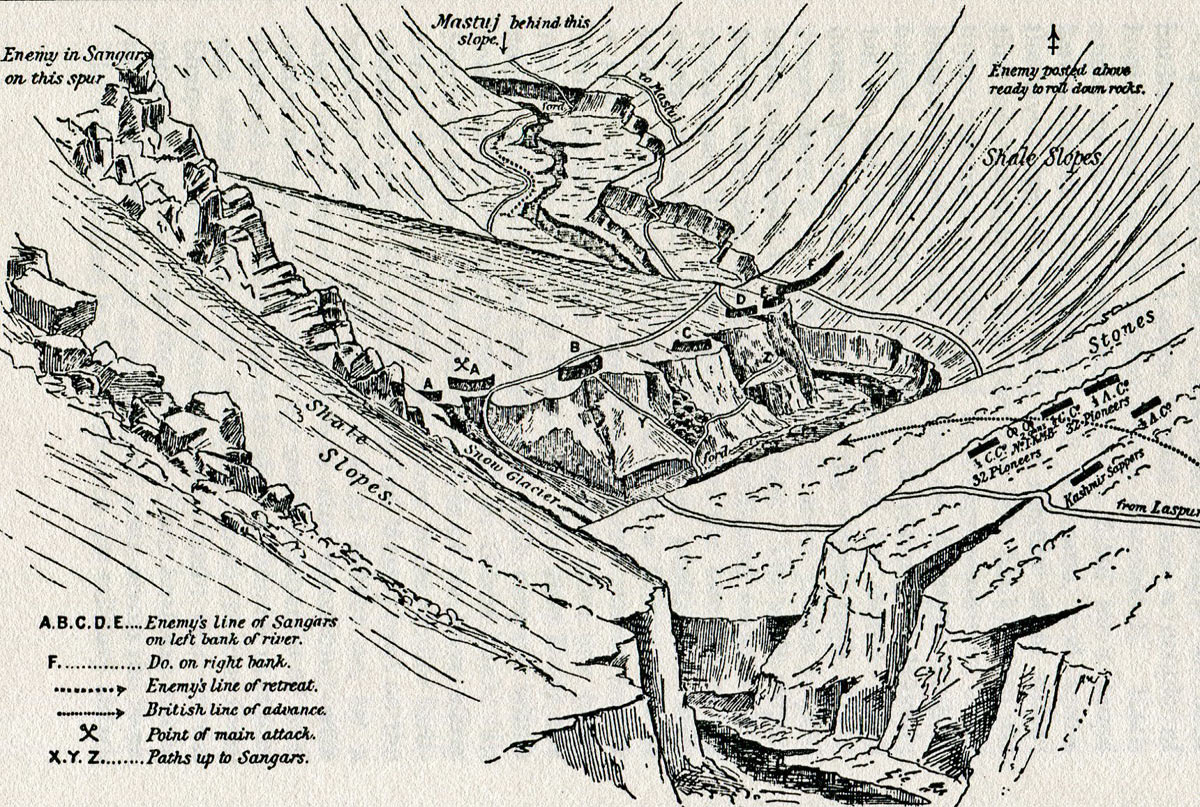

Chakalwat; plan by Captain Beynon: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Reconnaissance along the road to Mastuj showed that the Chitralis were in position in the Chakalwat Defile, three miles beyond Gasht, in strength and building sangars.

On 7th April 1895, Colonel Kelly arrived at Laspur with some 50 Nagar levies. More levies arrived on the same day and Kelly decided to attack the Chakalwat Defile, although many of the soldiers were suffering from snow blindness and the rest of the column was still on the track from Ghizr.

The attack went in on 9th April 1895, with support from the mountain guns and the Chitralis were driven from the position. Kelly’s column suffered 4 wounded men while the Chitralis had some 40 to 60 men killed by rifle and gunfire. The column marched into Mastuj Fort.

Kelly spent three days at Mastuj Fort, collecting supplies, bringing up the rest of the column and repairing the bridge over the Yarkhun River. He marched out on 13th April 1895 towards Chitral.

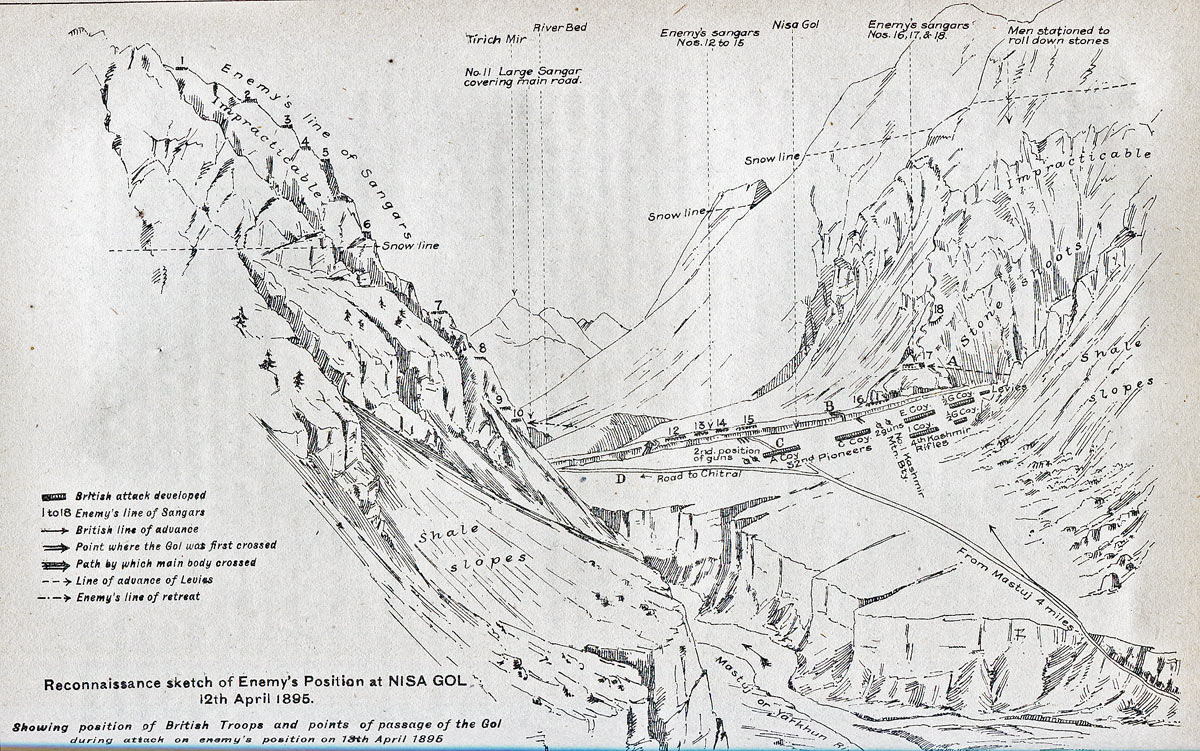

Nisa Gol, plan by Captain Beynon: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The action at Nisa Gol:

The Chitralis were in position at Nisa Gol, where a ravine joins the river valley from the north.

Nisa Gol: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The Chitralis had built sangars on the far side of the ravine, covering the road that ran along the north cliff of the river and more sangars above the south cliff. The British attack went in at around 10am, supported by gunfire from Stewart’s section. Ladders were used to cross the ravine and turn the Chitrali flank causing the Chitralis to withdraw.

It was estimated that the Chitrali force comprised around 1,500 men, with a small number of Umra Khan’s men, all armed with Martini-Henry or Snider breach loading rifles. The Chitrali commander was Muhammad Isa.

British/Indian casualties were 7 killed and 13 wounded. Chitrali casualties were reported by locals as 60 killed and 100 wounded.

On 15th April 1895, the column resumed its march to Kusht and then to Lun. On 17th April, instead of following the river road, where Ross and Edwardes had come to grief, Kelly marched up into the mountains via Drasan and Lun. In this way, all the defiles along the river route, including the Koragh, were bypassed.

On 18th April 1895, the column reached Koghazi, where Kelly received a letter from Robertson in Chitral, saying that the besieging force of Sher Afzul and Umra Khan had withdrawn and the siege of Chitral Fort was over. The advance of Kelly’s column, with the more distant threat of Low’s relieving force from the south, had forced the abandonment of the siege.

On 20th April 1895, Kelly’s column marched into Chitral.

Map of the route taken by the Chitral Relief Expedition: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India: map by John Fawkes

The Chitral Relief Expedition:

On 14th March 1895, the Government of India ordered the mobilisation of a division based on Peshawar, in view of the situation in Chitral and the incursion into Chitral by Umra Khan, the Khan of Jandol and Dir. The division was placed under the command of Lieutenant General Sir Robert Low KCB.

On 21st March 1895, the Government of India received news of the attacks on the parties of Captain Ross and Lieutenants Edwardes and Fowler.

The base for the division to comprise the Chitral Relief Expedition was moved to Nowshera. Concentration started on 26th March 1895 and in two and a half weeks, 15,000 troops, with followers and transport animals, were assembled at Hoti Mardan and Nowshera.

1st King’s Royal Rifle Corps: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The Division comprised:

First Infantry Brigade: Brigadier General Kinloch: 1st Bedfordshire Regiment, 1st King’s Royal Rifle Corps, 15th Sikhs, 37th Dogras and 2 field hospitals.

Second Infantry Brigade: Brigadier General Waterfield: 2nd King’s Own Scottish Borderers, 1st Gordon Highlanders, 4th Sikhs, the Guides Infantry and 2 field hospitals.

Third Infantry Brigade: Brigadier General Gatacre: 1st Royal East Kent Regiment (the Buffs), 2nd Seaforth Highlanders, 25th Punjab Infantry, 2nd/4th Gurkha Rifles and 2 field hospitals.

Signallers of 1st Buffs: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Divisional Troops: 11th Bengal Lancers, Guides Cavalry, 13th Bengal Infantry, 23rd Punjab Pioneers, 15th Battery, Royal Artillery, No 3 Mountain Battery, Royal Artillery, No 8 Mountain Battery, Royal Artillery, No 2 (Derajat) Mountain Battery, 3 companies, Bengal Sappers and Miners, an Engineer Park, 3 field hospitals and a veterinary field hospital.

34th Punjab Pioneers joined the division at the end of March 1895.

Lines of Communications Troops: 1st East Lancashire Regiment. 29th Punjab Infantry, 30th Punjab Infantry, No 4 (Hazara) Mountain Battery, 2 field hospitals and a veterinary field hospital.

The Relief of Chitral was the first expedition to take the Indian and British armies over the Malakand Pass into Swat and Jandol. The British had little information on the country that lay to the north of Mardan. There were no roads, only tracks over the mountains. The first range of border hills was 3,000 to 6,000 feet in height. Beyond, were further ranges of high mountains and three substantial rivers without bridges; border hills, then the Swat River; Laram Range up to 6,000 feet, then the Panjkora River; Janbati Range and the Dir Valley; the Lowarai Pass into the valley of the Kunar River.

Until roads could be built, the force would have to rely on pack animals to move supplies. Some 30,000 mules and camels were used in support of the force. No tents were taken and the baggage allowance was 40 lbs for officers and 10 lbs for soldiers, including greatcoat. The weather was snow, wind, rain and fierce sun shine.

Dir Fort: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

In order to reach Jandol and Dir and then to enter Chitral, the Chitral Relief Force had to cross the territory of a number of other tribes and rulers. While in general, agreements were reached to secure permission from these rulers and to ensure their neutrality or active assistance, it is doubtful whether individual tribesmen in these areas could resist the opportunity of a fight with the invading troops of the British Raj, at least at first.

On 30th March 1895, the Divisional Headquarters and the Second and Third Brigades moved from Nowshera to Hoti Mardan. The divisional cavalry and guns were distributed among the brigades. The First Brigade followed on the next day.

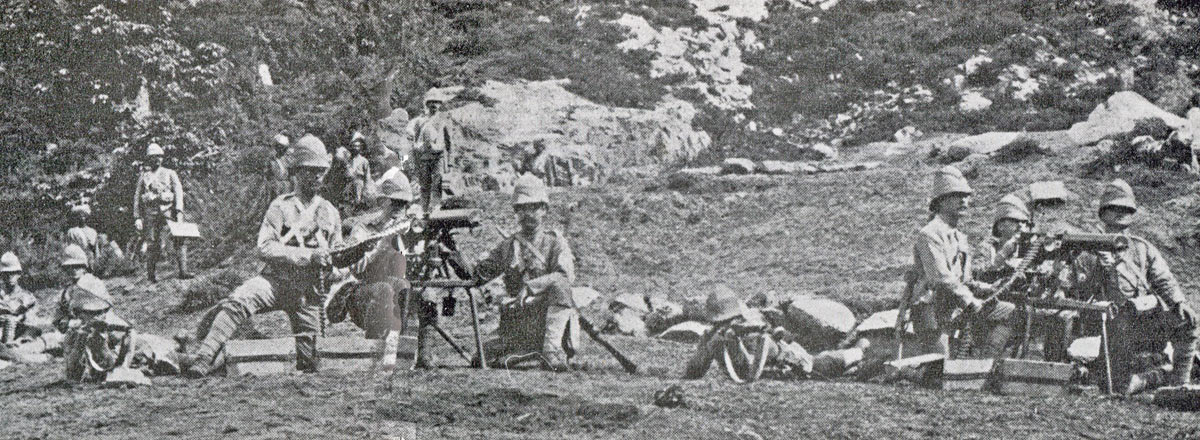

Maxim Gun detachment of 1st King’s Royal Rifle Corps: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

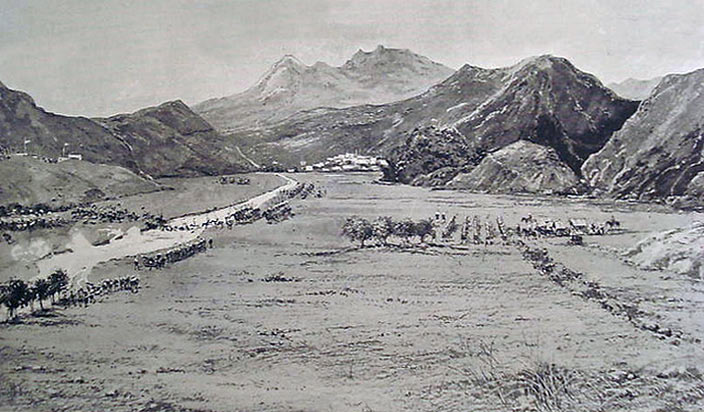

The first move required the Chitral Relief Force to cross the range of mountains running west to east, before advancing into the Swat Valley. There were three points at which these mountains might be crossed; the passes of Malakand, Shakot and Morah. Reconnaissance showed that Shakot and Morah were held by 6,000 and 13,000 tribesmen respectively, while Malakand was held by a few hundred. A feint was made towards the Shakot Pass and then the whole Chitral Relief Force concentrated to force the Malakand Pass on 3rd April 1895. The attack was carried out by the Second Brigade supported by the First Brigade. The Third Brigade remained at Dargai.

Chitral Relief Expedition encamped below the Malakand Pass: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

As soon as the British intention became clear tribesmen speedily assembled in considerable numbers to defend the Malakand Pass.

1st Gordon Highlanders storming the Malakand Pass: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India: picture by SW Lincoln

In the course of some five hours, the infantry battalions of the two brigades fought their way up the pass, with the support of fire from the mountain batteries. The tribesmen retreated and were pursued by the Bedfords and the 37th Dogras as far as Khar.

It was assessed that there were some 12,000 tribesmen involved in the battle, of which it was believed that around a half were equipped with firearms. Tribal casualties were estimated at around 500 killed. British/Indian casualties were 11 killed and 51 wounded. The Indian Government history records that 16,563 rifle rounds were fired with 446 artillery rounds.

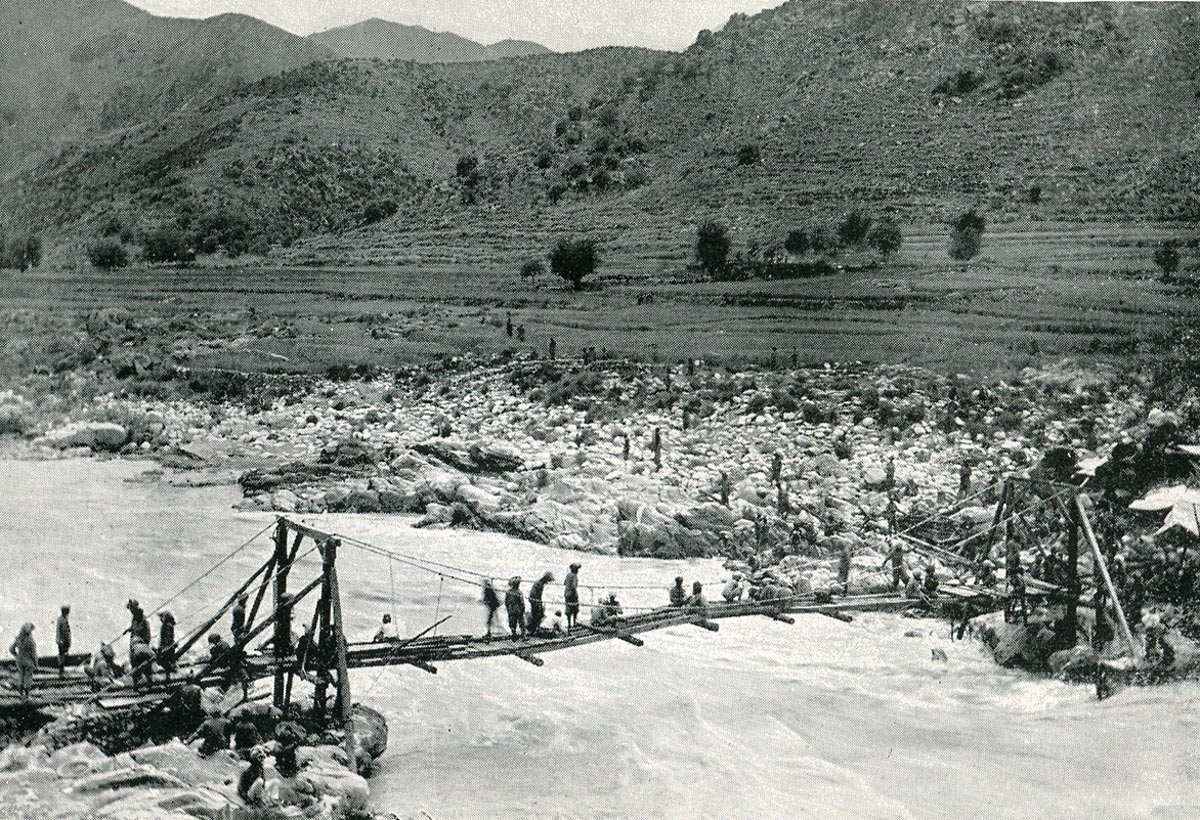

11th Bengal Lancers crossing the Swat River: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

The resistance to the Chitral Relief Force was not primarily Chitrali. The incursion into tribal territory aroused the resentment of all the tribes in the region, particularly the Swatis, urged on by many of the Imams. The resistance was co-ordinated, if not actually led, by Umar Khan, the Khan of Jandol and Dir, who had moved south from Chitral to take part in the fighting.

Highlanders attacking: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

While the pretext for the invasion of Jandol was the relief of Chitral and the release of the British and sepoy prisoners from Edwardes’ and Fowler’s party held by Umar Khan, the continued independence of Jandol, Dir, Swat and Chitral was now a major issue.

On 4th April 1895, the First Brigade moved down into the Swat Valley and the Second Brigade took over the top of the Malakand Pass, leaving the Third Brigade at Dargai.

Those tribesmen who had gathered in the other two passes were now massing in the Swat Valley and the First Brigade was forced to fight its way through to the Swat River at Khar during the 4th April 1895. The Second Brigade came up on the 5th April.

On 5th April 1895, negotiations took place with various tribal leaders. Mohammed Sharif Khan, the exiled Khan of Dir who had been expelled from Dir when it was conquered by Umra Khan, was permitted to cross the Swat and resume control of Dir. This action enabled the Chitral Relief Force to move through Dir without resistance and kept a number of other tribes, over whom the Khan of Dir exerted influence, out of the fighting.

Guides Cavalry in action: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Between 6th and 8th April 1895 the First Brigade conducted operations along the Swat River upstream and to the north of the river, while supplies for a further move were brought over the difficult Malakand Pass.

On 9th April 1895, the First Brigade moved west, to open the route across the Panjkora River through Jandol, while the Second Brigade moved into the Swat Valley and the Third Brigade moved up to Khar.

On that day, a force from the First Brigade, comprising 11th Bengal Lancers, a squadron of Guides Cavalry, the 4th Sikh Regiment, the Guides Infantry and the Derajat Mountain battery patrolled up to the Panjkora River at Sado and found it to be fordable. The pass leading to the river at Kamrani was found to be feasible.

Information was now received that Umra Khan was at Mundah, on the far side of the Panjkora River. Umra Khan released 6 Mohammedan sepoys captured at Reshun with Fowler and Edwardes.

On 11th April 1895, the Second Brigade concentrated at Sado and Khungai, where they were fired on by tribesmen on the far side of the Panjkora River. A bridge was built across the river and completed on 12th April. 6 companies of the Guides Infantry, Commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Battye, were sent across the river to guard the bridgehead and to carry out punishment raids on the neighbouring villages for firing on the troops.

During the night, the Panjkora River rose and debris brought downstream by the flood carried away part of the bridge, stranding the Guides on the far bank.

Guides Infantry: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Companies of the Guides marched out to conduct the punishment raids, advancing up the right bank of the Jandol River. While his companies were dispersed, Colonel Battye took up a position by the Jandol River. Tribesmen assembled in the area of Kotkai and began to advance on the Guides. Colonel Battye was given orders by heliograph to withdraw his battalion to the bridgehead on the Panjkora River. Battye held his position on the Jandol River, to enable his companies to withdraw and came under sustained attack. Supporting rifle and gunfire was provided from the brigade positions on the far side of the Panjkora, while the Guides fell back under pressure from the tribesmen. During the withdrawal, Battye was shot dead. The Guides fell back across the Jandol River and reached the Panjkora River bridgehead. During that night, the Gordon Highlanders and a mountain battery provided covering fire from the left bank of the Panjkora River.

Suspension Bridge built over the Panjkora River by Major Aylmer VC: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Chitral Relief Force in action: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Between 14th and 16th April 1895, a suspension bridge was built over the Panjkora River to avoid the problem of damage from debris coming down the flooded river.

On 17th April 1895, the Third Brigade and part of the Second Brigade crossed the Panjkora River and the Third Brigade marched up the Jandol valley. A large body of tribesmen advanced from Mian Kilai. The Third Brigade moved forward to attack, driving the tribesmen from ridge to ridge. The tribesmen fell back and finally withdrew to the west. It was estimated that there were some 3 to 4,000 of the Mamund and Salarzi Tarkanri tribes present in the action.

The Second and Third Brigades occupied Mian Kilai and Mundah on 18th April 1895.

In view of General Low’s increasing concern over the garrison at Chitral Fort, on 18th April 1895, General Gatacre pressed on to Barwa with a small force comprising 1st Buffs, 2nd/4th Gurkha Rifles, the Derajat Mountain Battery, a half company of Bengal Sappers and Miners and a field hospital section.

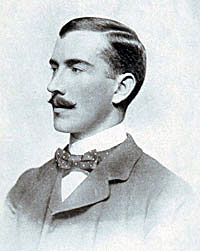

William Gatacre as a colonel in India in 1890: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

On 13th April 1895, Lieutenant Edwardes arrived from Umra Khan, with a message asking why his territory was being invaded by the British. Sir Robert Low replied that, if Umra Khan released the remaining prisoners and desisted from opposing the Chitral Relief Force, he would be permitted to retain his territory. On 15th April 1895, Sir Robert Low sent Umra Khan a message saying that, in view of his delay, the terms were no longer available to him. On 16th April 1895, Umra Khan released Fowler, who arrived at the British camp at Sado and asked to be enabled to retain his territory. Sir Robert Low replied that those terms were no longer available and Umra Khan fled to Afghanistan.

On 19th April 1895, Gatacre’s Third Brigade marched through the Janbatai Pass and, on 20th April, reached Bandai. In the light of information that the garrison in Chitral Fort were hard pressed, Low ordered Gatacre to press on with a small column. Gatacre organised two columns, the first being 2nd/4th Gurkha Rifles, with mountain guns and sappers and miners, the second being 1st Buffs with mountain guns and sappers and miners. In each case, the guns were from 2nd Derajat Mountain Battery. The columns advanced to Bandai, where the information was received that Sher Afzal had fled from Chitral and the siege of the fort lifted.

Devonshire Regiment Maxim Gun team: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India

Gatacre continued his advance with 2 maxim guns from the Devonshire Regiment replacing the mountain guns. The route to the Lowari Pass and the valley of the Kunar River was extremely difficult and sections of the road had to be rebuilt and new bridges constructed. Much of the fatiguing work was carried out by the soldiers of the Buffs.

Sher Afzal and several of his main supporters were captured by the Khan of Dir, who handed them over to the British in their camp at Dir. The leading persons were exiled to India with Sher Afzal.

Gurkhas crossing the Lowari Pass: Siege and Relief of Chitral, 3rd March to 20th April 1895 on the North-West Frontier of India